Adjuvant S-1 chemotherapy after curative resection of gastric cancer in Chinese patients: assessment of treatment tolerability and associated risk factors

Hong Kong Med J 2017 Feb;23(1):54–62 | Epub 14 Dec 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164885

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Adjuvant S-1 chemotherapy after curative resection of gastric cancer in Chinese patients:

assessment of treatment tolerability and associated risk factors

Winnie Yeo, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

KO Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)2;

Ada LY Law, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)3;

Conrad CY Lee, FRCP, FRCR4;

CL Chiang, MB, ChB, FRCR5;

KH Au, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)6;

Frankie KF Mo, MPhil, PhD7;

TH So, BChinMed, MB, BS2;

KC Lam, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)8;

WT Ng, MD3;

L Li, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)8

1 Department of Clinical Oncology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Clinical Oncology, The University of Hong Kong,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

3 Department of Clinical Oncology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern

Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

4 Department of Clinical Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok,

Hong Kong

5 Department of Clinical Oncology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong

Kong

6 Department of Clinical Oncology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong,

Hong Kong

7 Comprehensive Clinical Trials Unit, Department of Clinical Oncology, The

Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

8 Department of Clinical Oncology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong

Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Winnie Yeo (winnieyeo@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The use of adjuvant chemotherapy

with S-1 (tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil potassium)

has been shown to improve the outcome of patients

with gastric cancer. There are limited data on

the tolerability of S-1 in Chinese patients. In this

multicentre retrospective study, we assessed

the toxicity profile in local patients.

Methods: Patients with stage II-IIIC gastric

adenocarcinoma who had undergone curative

resection and who had received S-1 adjuvant

chemotherapy were included in the study.

Patient demographics, tumour characteristics,

chemotherapy records, as well as biochemical,

haematological, and other toxicity profiles were

extracted from medical charts. Potential factors

associated with grade 2-4 toxicities were identified.

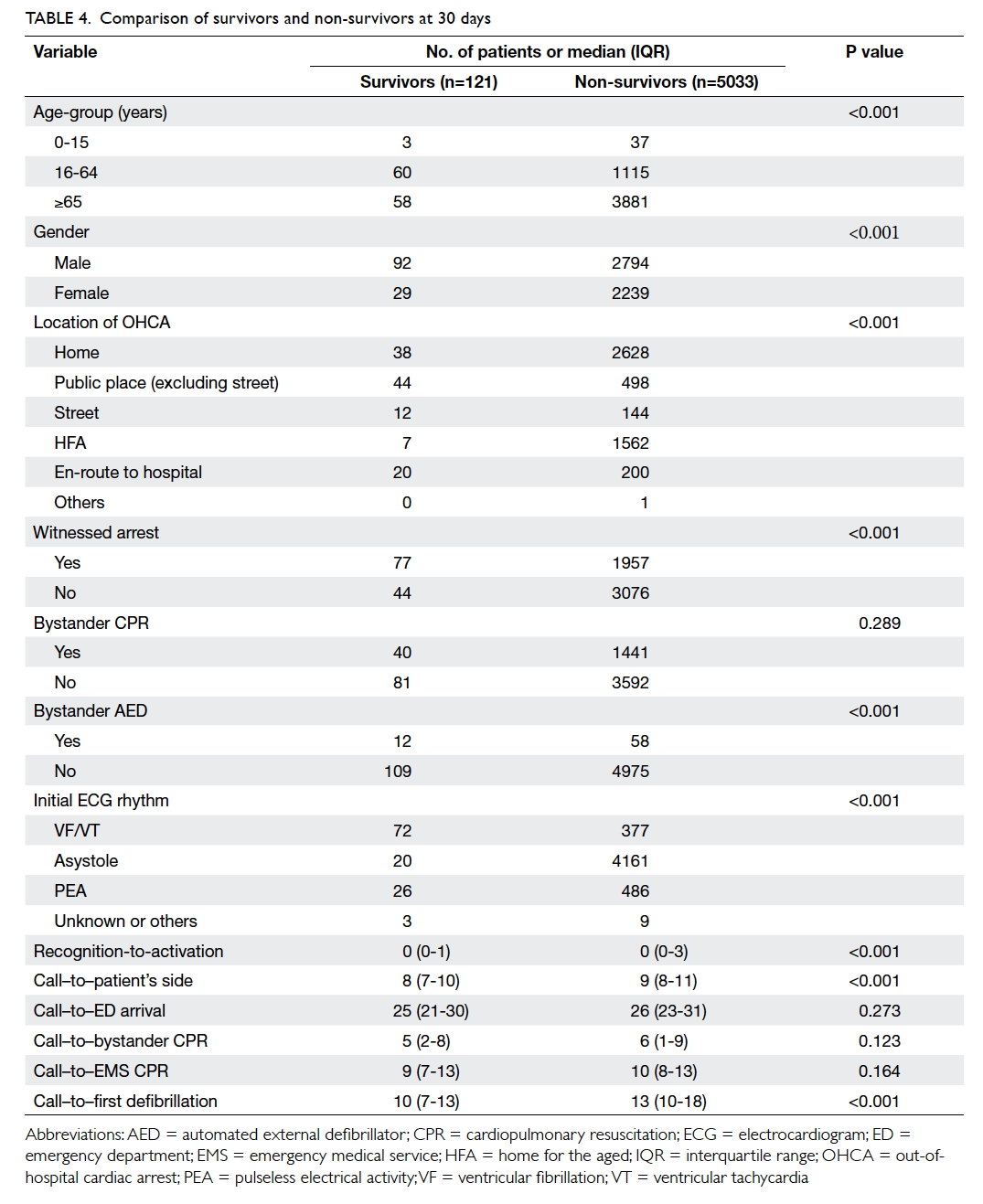

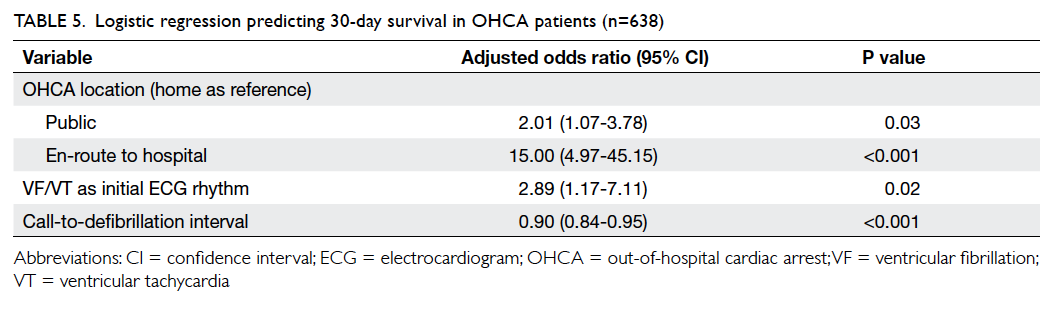

Results: Adjuvant S-1 was administered to 30

patients. Overall, 19 (63%) patients completed eight

cycles. The most common grade 3-4 adverse events

included neutropaenia (10%), anaemia

(6.7%), septic episode (16.7%), diarrhoea (6.7%),

hyperbilirubinaemia (6.7%), and syncope (6.7%).

Dose reductions were made in 22 (73.3%) patients

and 12 (40.0%) patients had dose delays. Univariate

analyses showed that patients who underwent total

gastrectomy were more likely to experience adverse

haematological events (P=0.034). Patients with nodal

involvement were more likely to report adverse non-haematological

events (P=0.031). Patients with a

history of regular alcohol intake were more likely to

have earlier treatment withdrawal (P=0.044). Lower

body weight (P=0.007) and lower body surface area

(P=0.017) were associated with dose interruptions.

Conclusions: The tolerability of adjuvant S-1 in our

patient population was similar to that in other Asian

patient populations. The awareness of S-1–related

toxicities and increasing knowledge of potential

associated factors may enable optimisation of S-1

therapy.

New knowledge added by this study

- In line with the published data, adjuvant S-1 therapy has a tolerable toxicity profile among local patients who have undergone curative resection for gastric cancer. Total gastrectomy and nodal involvement are potential factors associated with adverse events. Lower body weight and lower body surface area are potential factors associated with dose interruptions.

- For gastric cancer patients in whom adjuvant S-1 therapy is planned, close monitoring of those who have identifiable risk factors may enable early recognition of adverse events during therapy. This may enable earlier intervention with supportive therapy and improve treatment outcome.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the second most common cause

of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with 988 000

new cases and 736 000 deaths per year.1 Surgery is

the main treatment for operable gastric cancer but

recurrence rates are high and about 40% to 80% of

patients develop relapsed disease after surgery. The

use of adjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to

improve patient outcome.2 3 4 5 After curative resection,

common adjuvant chemotherapy regimens that have

been recently adopted in many parts of Asia include

oral administration of S-1 (tegafur, gimeracil,

and oteracil potassium) based on the Adjuvant

Chemotherapy Trial of S-1 for Gastric Cancer

(ACTS-GC) study conducted in Japan,4 as well as

oxaliplatin-capecitabine combination chemotherapy

based on the Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin Adjuvant

Study in Stomach Cancer study.5 These studies have

shown that adjuvant S-1 for 1 year or oxaliplatin-capecitabine

combination chemotherapy for 6

months following curative gastrectomy with D2

lymph node dissection increases both overall survival

(OS) and relapse-free survival in pathological stage

II or III gastric cancer.4 5

S-1 is an oral anticancer agent comprising

tegafur, 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine (CDHP), and

oteracil potassium (Oxo) at a molar ratio of 1:0.4:1.6

Tegafur is a prodrug of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU); CDHP

is a potent reversible inhibitor of 5-FU degradation;

and Oxo is an inhibitor of the enzyme orotate

phosphoribosyltransferase (OPRT) that catalyses

the phosphorylation of 5-FU.6 Pharmacokinetic

analyses have confirmed that S-1 has potent anti-tumour

activity, and oral S-1 administration

results in a similar serum concentration of 5-FU to

intravenous 5-FU whilst sparing patients the need

for continuous intravenous infusion of 5-FU and

consequent toxicity.7 Nonetheless early studies have

also shown that toxicity profiles may differ between

Asian and non-Asian patients. In earlier studies in

Japanese patients, the dose-limiting toxicity was

bone marrow suppression that occurred prior to

gastrointestinal adverse events. In contrast, studies

in non-Asian patients revealed that diarrhoea

associated with abdominal discomfort and cramping

was the principal dose-limiting toxicity and bone

marrow suppression was not.8 This might be due

to the varied activity of OPRT between different

populations. In fact, OPRT activates 5-FU in the

bowel mucosa; patients with higher OPRT activity

might be expected to experience a higher incidence

of gastrointestinal adverse effects prior to bone

marrow toxicity.9

In the ACTS-GC study, the adverse events of

adjuvant S-1 were reported to be generally mild,

with 65.8% of patients being able to complete the

planned 1 year of therapy.4 While it has been known

that patients in the West have a different toxicity

profile to their Japanese counterparts,10 there are

limited data on tolerability of S-1 among Chinese

patients. In this multicentre retrospective study, we assessed the toxicity and tolerability profiles

of Hong Kong Chinese patients with gastric cancer

who had received adjuvant S-1 chemotherapy.

Methods

This was a retrospective study carrying out between

June 2013 and February 2016, and involved six local

centres in Hong Kong: Pamela Youde Nethersole

Eastern Hospital, Princess Margaret Hospital, Prince

of Wales Hospital, Tuen Mun Hospital, Queen

Mary Hospital, and United Christian Hospital.

This study has been approved by the institutional

ethics committee of each participating centre with

patient consent waived. Patients with

stage II-IIIC gastric adenocarcinoma according to

American Joint Committee on Cancer,11 who had

completed curative surgical treatment and who

had undergone S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy, were

included. Patients with stage IV disease and who

had had prior therapy with S-1 in the neoadjuvant

setting were excluded.

Adjuvant S-1 was started at least 3 weeks after

curative surgery. The intended dose of S-1 was based

on that published in the ACTS-GC trial,4 and was

40 mg/m2 twice daily for 4 weeks followed by 2

weeks of rest for each cycle. Specifically, during the

treatment weeks, patients with body surface area

(BSA) of <1.25 m2 received 80 mg daily; those with

BSA of 1.25 m2 to <1.5 m2 received 100 mg daily; and

those with BSA of ≥1.5 m2 received 120 mg daily. As

clinically indicated, dose reductions were considered

one dose level at a time; in general, one dose level

reduction refers to reducing the prior daily dose by

20 mg, eg from 120 mg to 100 mg daily. As renal

impairment has been associated with increased

incidence of myelosuppression, dose reduction

by one dose level was made in patients who had a

creatinine clearance of 40-49 mL/min. A maximum

of eight 6-weekly cycles were administered. The

dose of S-1 was reduced in patients with significant

toxicities, as assessed by the respective clinician-in-charge. Complete and differential blood count

and serum chemistry were performed before each

6-week cycle. All patients had mid-cycle follow-up

with complete and differential blood counts and

serum chemistry in the first cycle.

Patient charts were reviewed by investigators

at each centre for background information. S-1

chemotherapy records, as well as biochemical and

haematological profiles, were extracted. Adverse

events were graded according to the National

Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria

for Adverse Events (version 3.0).12 Adverse events

were documented during chemotherapy and for 28

days after the last dose of S-1. Dose interruption was

defined as a need for either any dose delay and/or

dose reduction.

Clinical characteristics are summarised as

number of patients and percentage (%) for categorical

variables, and medians with ranges for continuous

variables. The frequency of adverse events was

tabulated. Factors independently associated with

adverse events, dose interruptions, or earlier

withdrawal of S-1 were identified using the Pearson’s

Chi squared (χ2) test or the Fisher’s exact test if the

expected number in any cell was less than five for

categorical data or any cell with an expected count

of less than one for categorical data, and t test or

Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous data. A two-sided

P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS,

version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cory [NC], US).

Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated

as the period from the date of surgery to the date

of recurrence or death from any cause; OS was

calculated as the period from the date of surgery to

the date of death from any cause. Both DFS and OS

were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

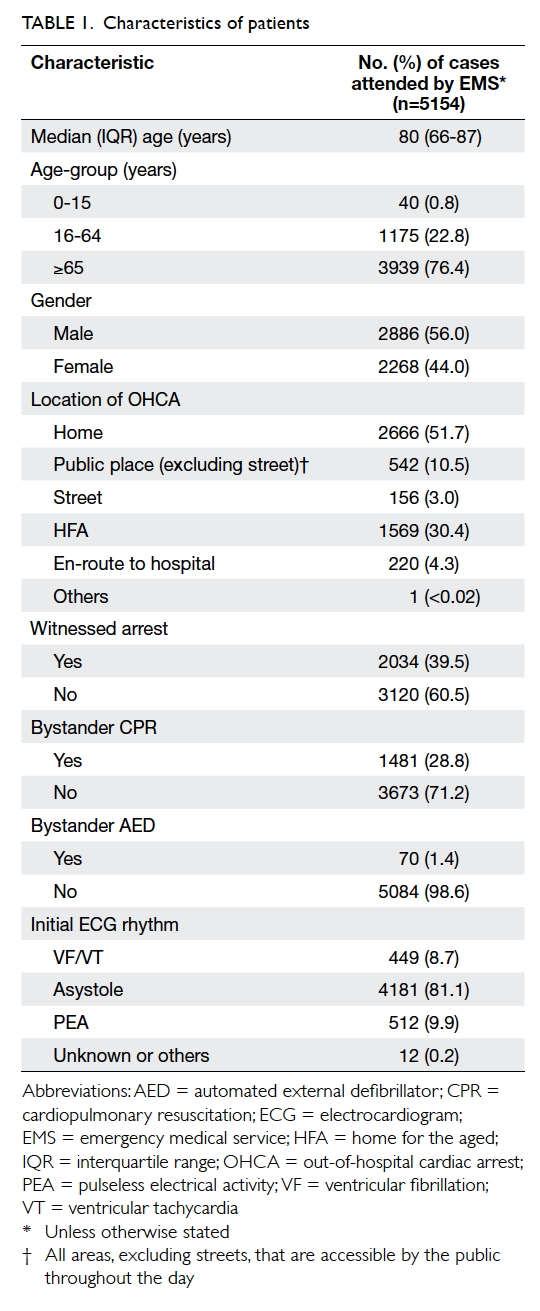

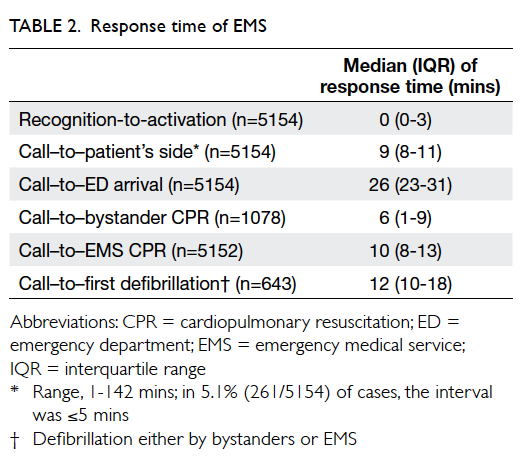

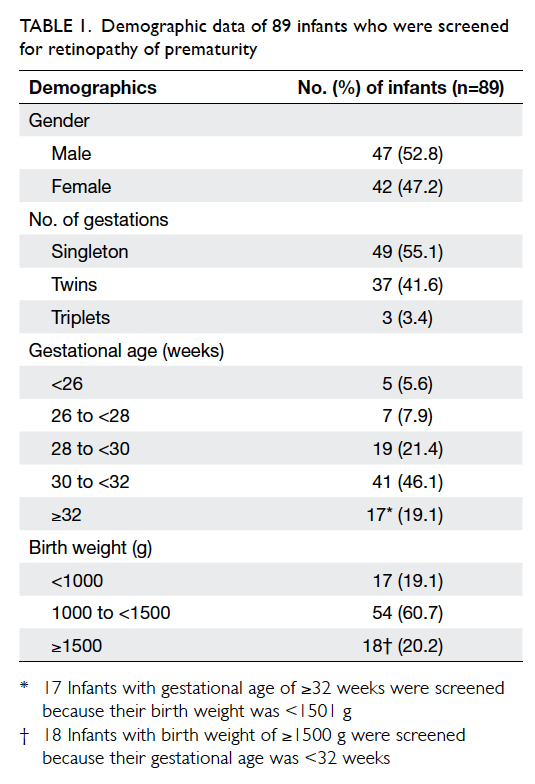

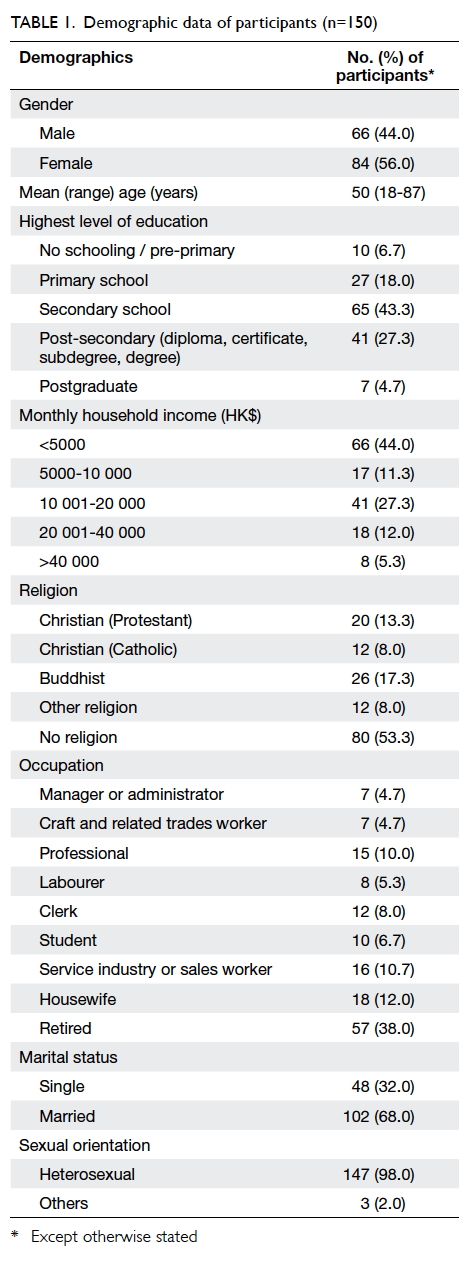

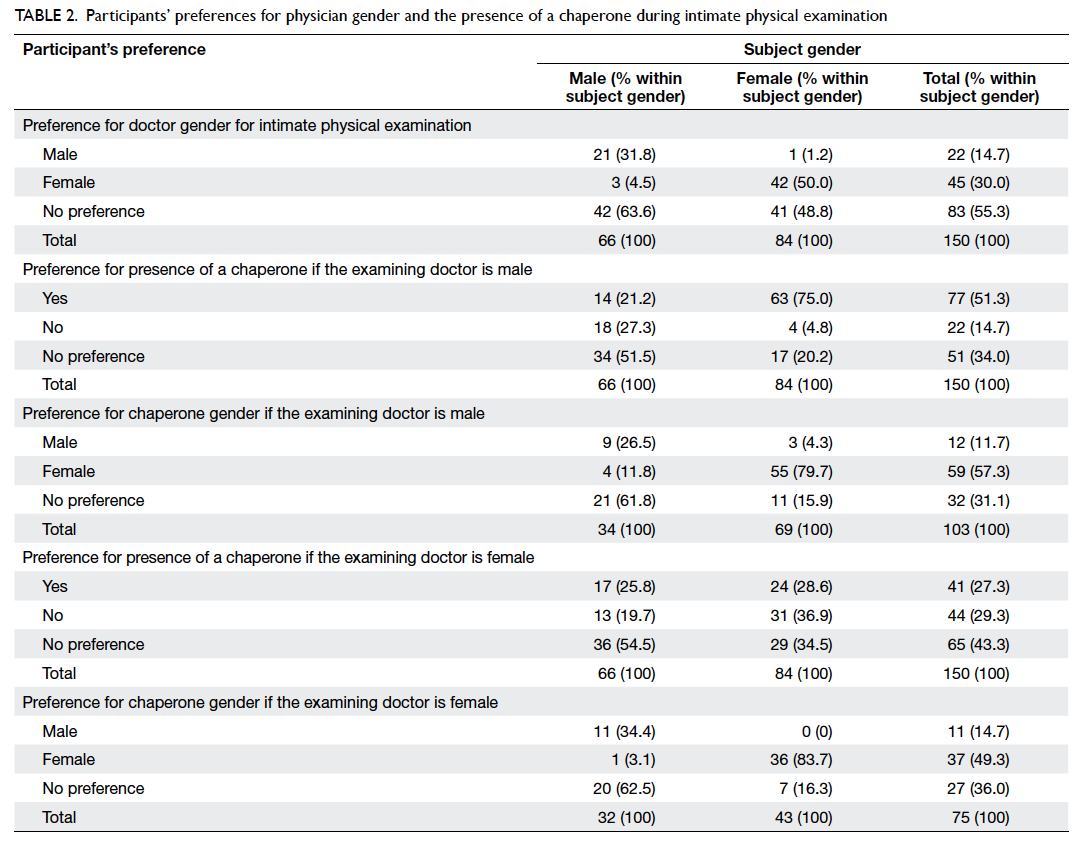

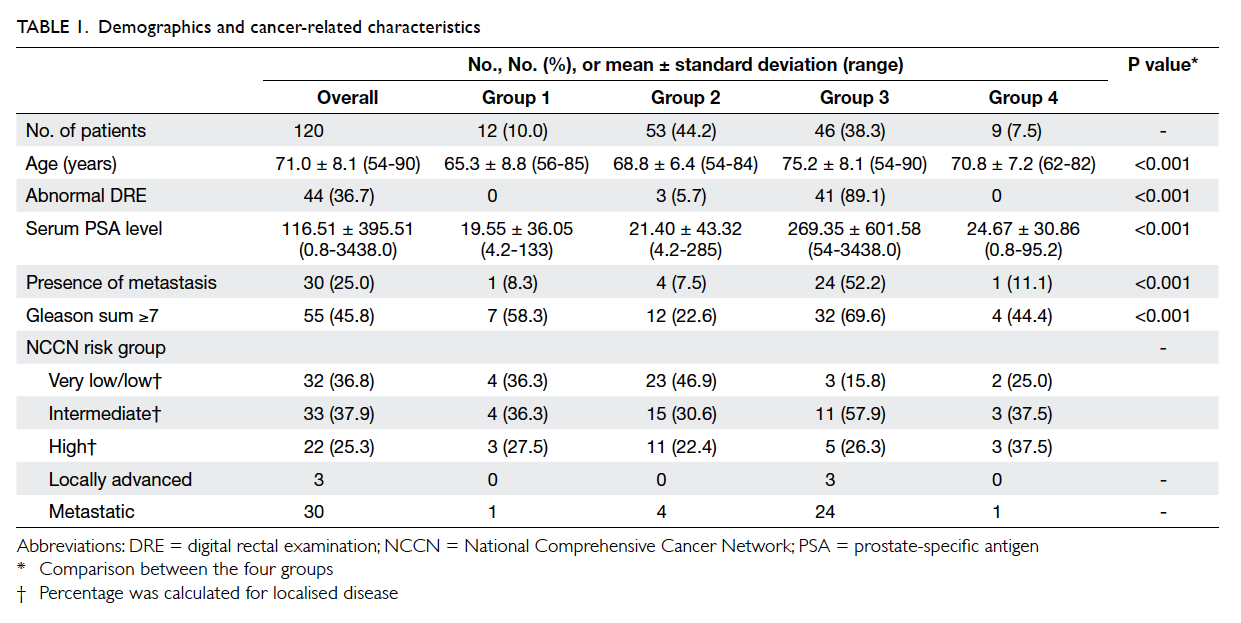

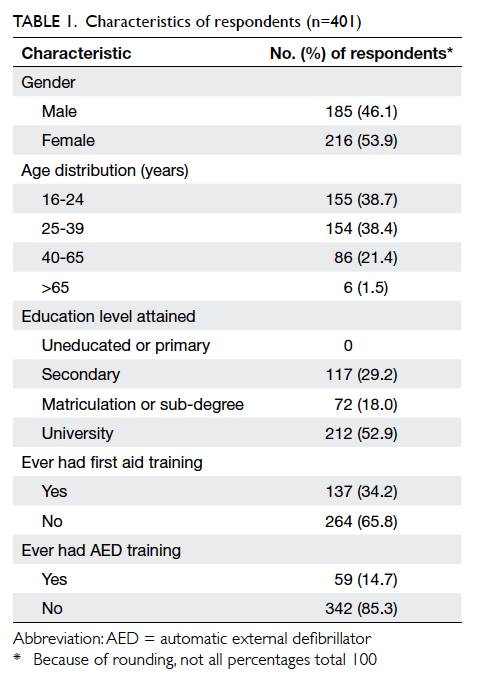

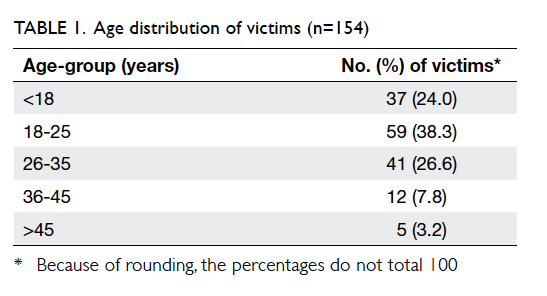

Characteristics of patients

Thirty patients met the eligibility criteria in the six

centres during the study period and were enrolled in

this study. Their baseline demographic and clinical

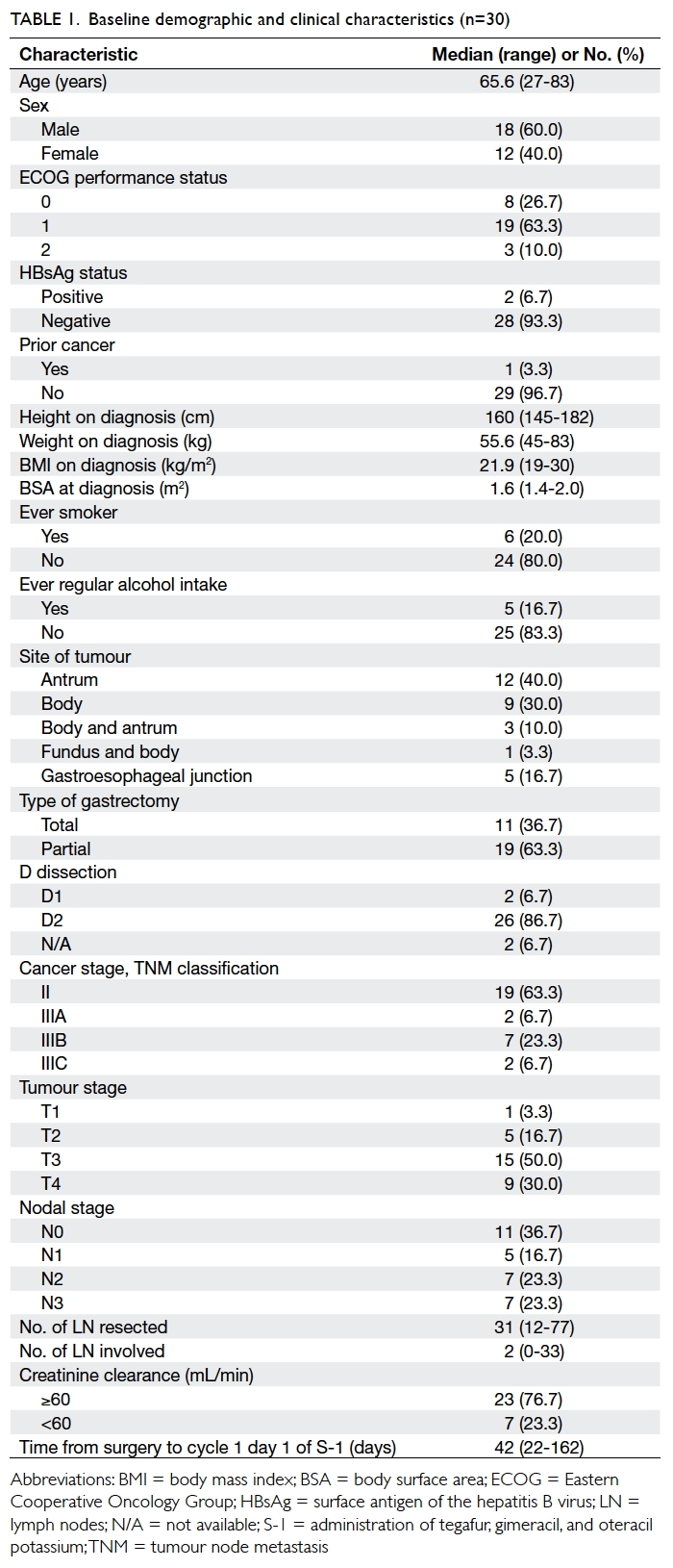

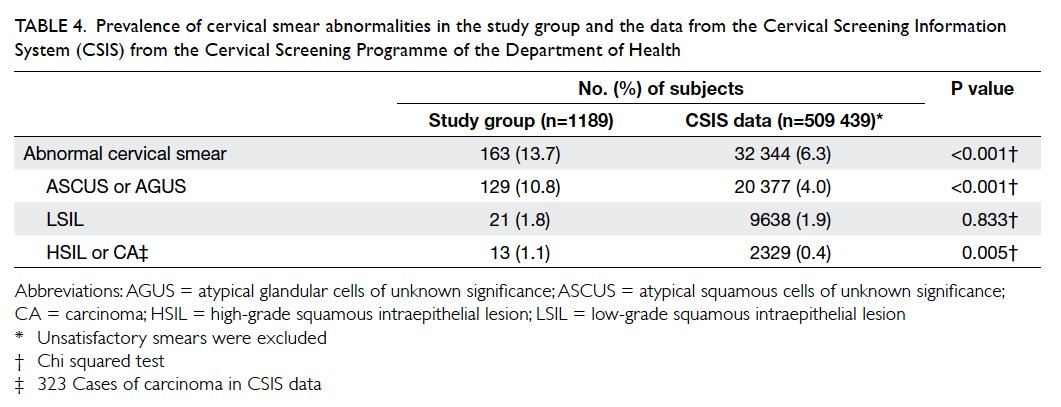

characteristics are shown in Table 1.

There were 18 males and 12 females with

a median age of 65.6 years. Of the patients, 27

(90%) had ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) performance status of 0 to 1. Total gastrectomy

was performed in 11 (36.7%) patients and partial

gastrectomy in 19 (63.3%). D2 dissection was

performed in 26 (86.7%) patients and two had D1

dissection; the details of two other patients were

unknown. The median number of lymph nodes

resected was 31. Cancer stage II disease was present in 19

(63.3%) patients and stage III in 11 (36.7%).

Of the 30 patients, two (6.7%), two (6.7%), one (3.3%),

two (6.7%), one (3.3%), three (10%), and 19 (63.3%) completed

one, two, three, four, five, six, and eight cycles of S-1

adjuvant chemotherapy, respectively. At the time of

data cut-off on 29 February 2016, one patient was still

on S-1, having completed six cycles of treatment. The

reasons for treatment withdrawal included toxicities

(n=5, 16.7%), patient refusal (3, 10%), recurrence

(2, 6.7%), and worsening of pre-existing Parkinson’s

disease (1, 3.3%).

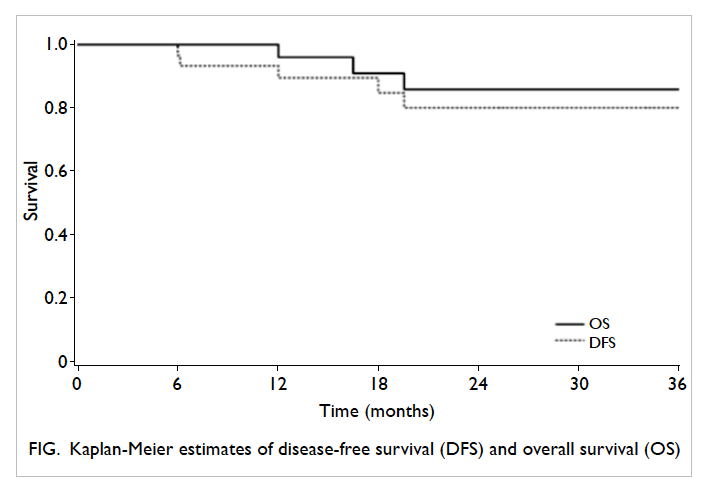

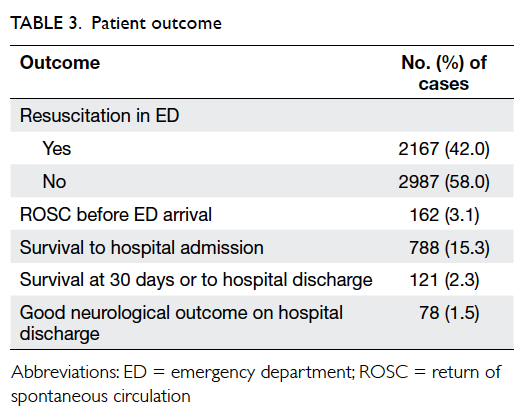

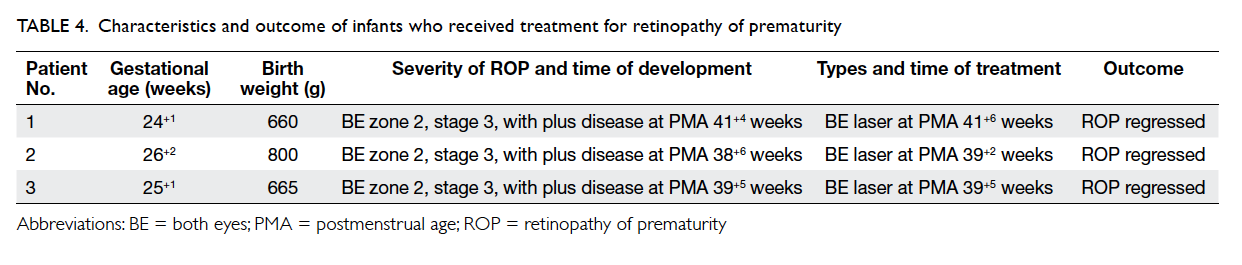

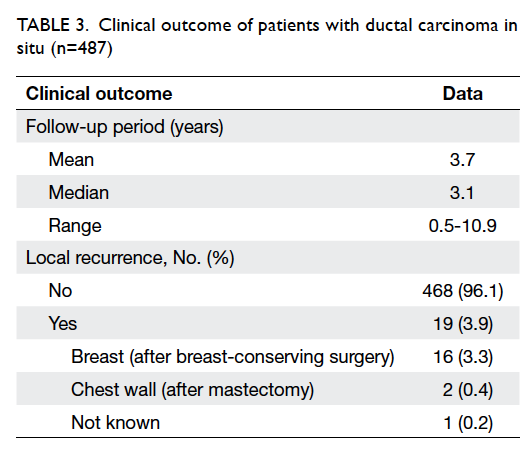

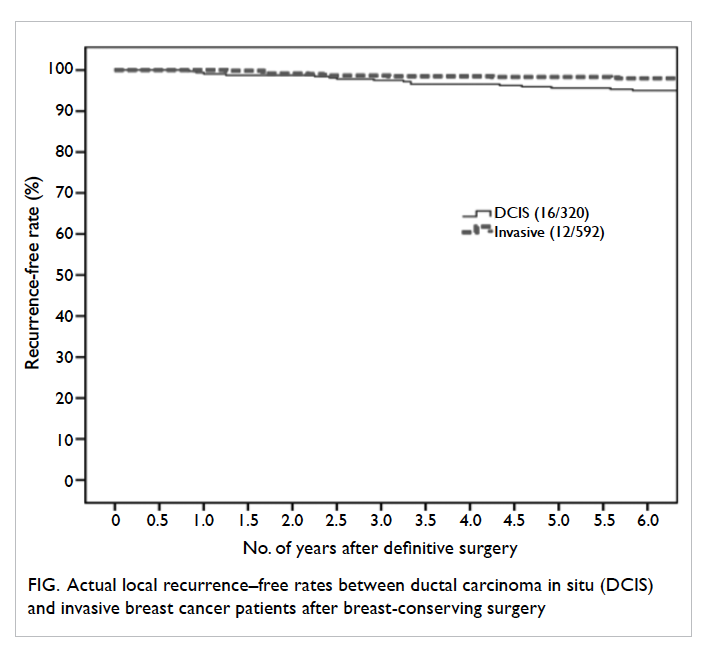

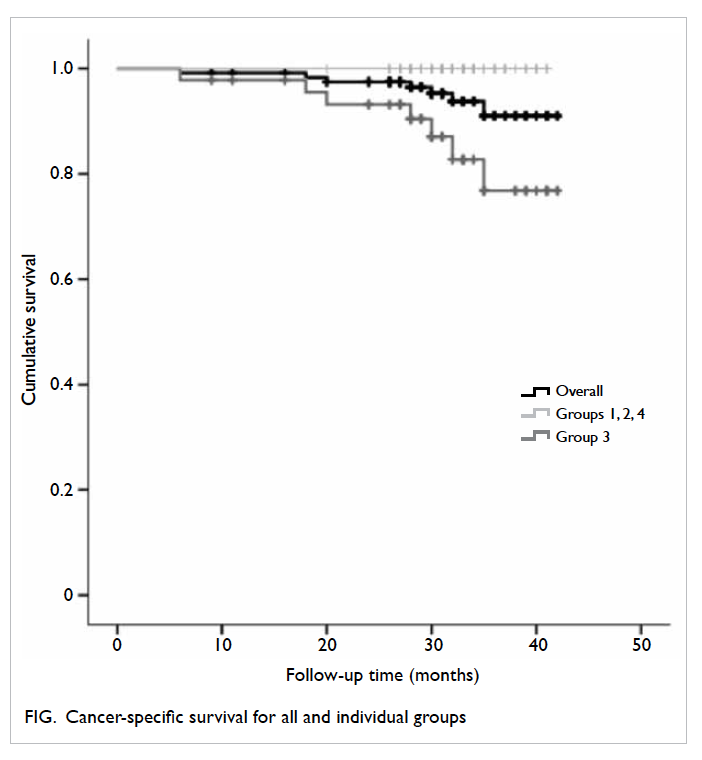

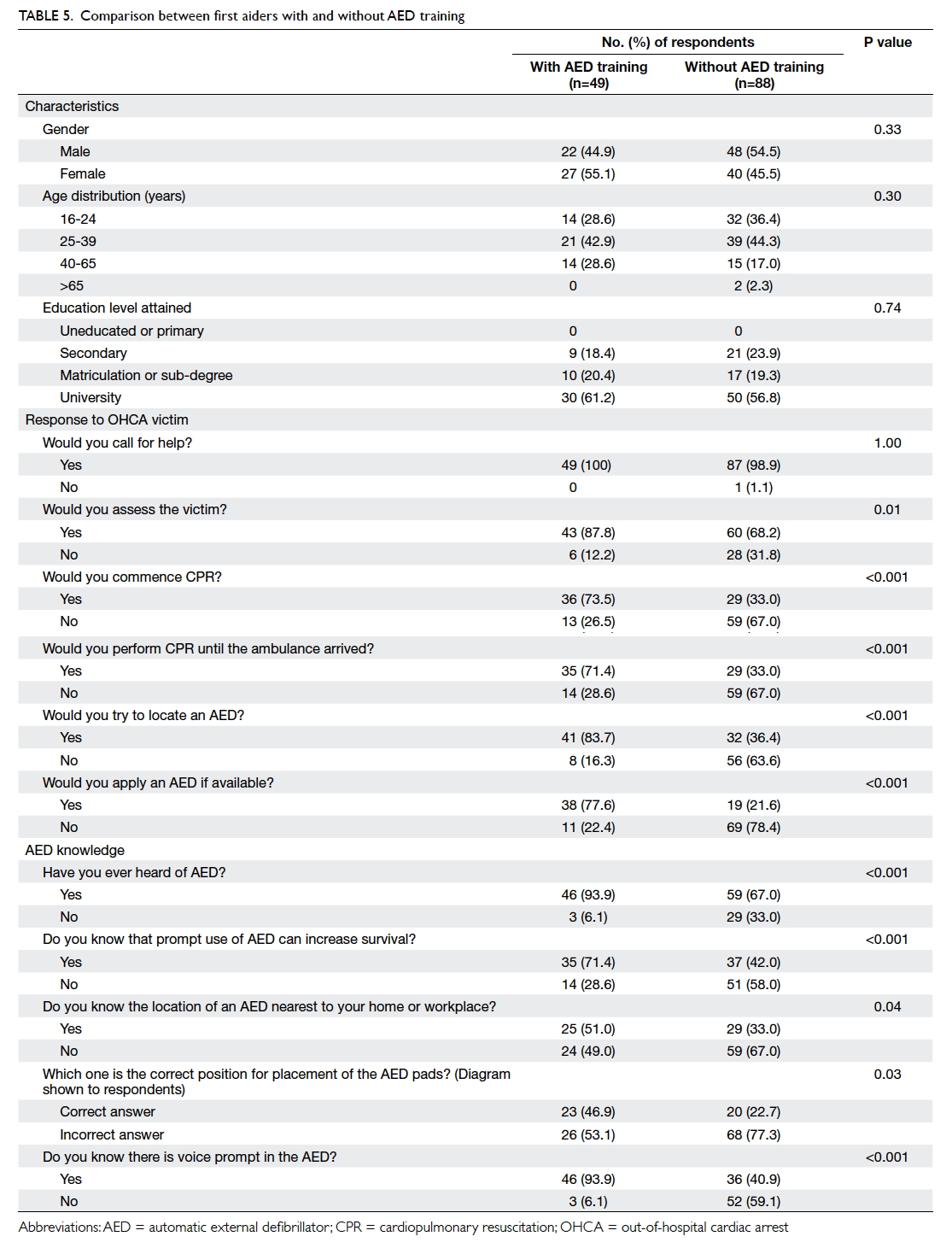

Patient survival

The median follow-up period was 25.3 months

(range, 16.3-29.2 months). Three patients died and

two experienced recurrence (lung and peritoneum).

The 3-year DFS and OS rates were 80.2% and 85.9%,

respectively (Fig).

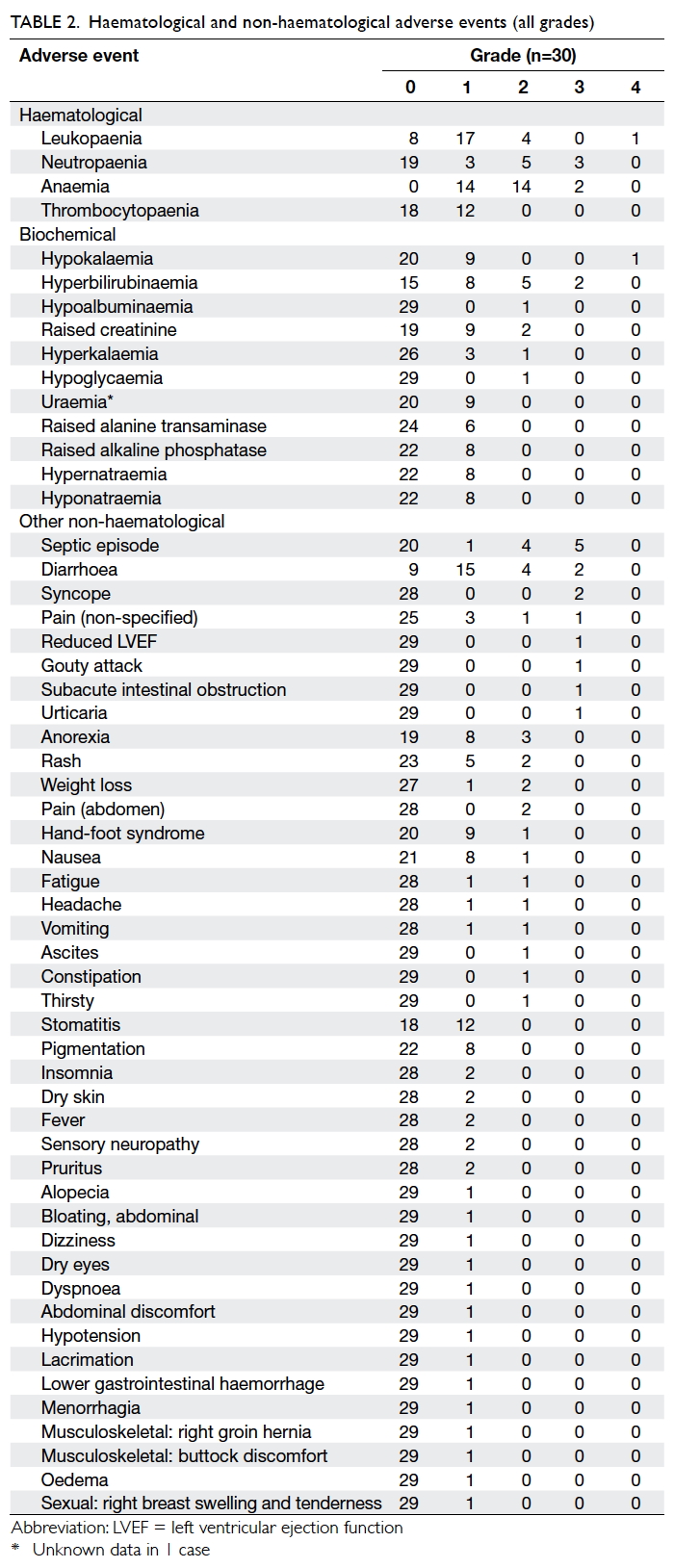

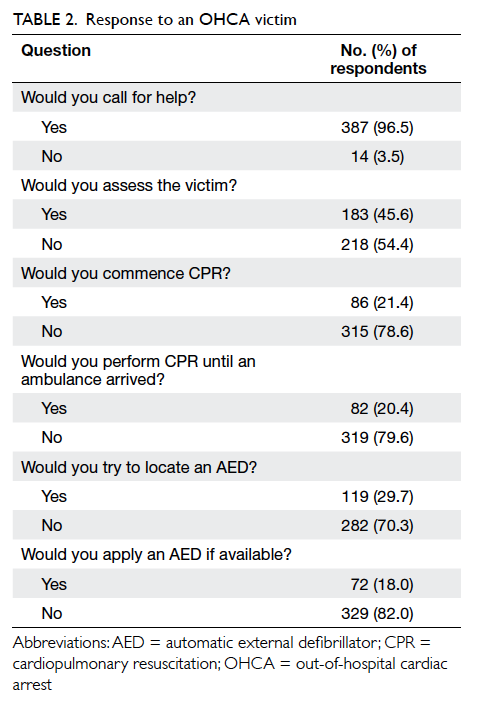

Tolerability data

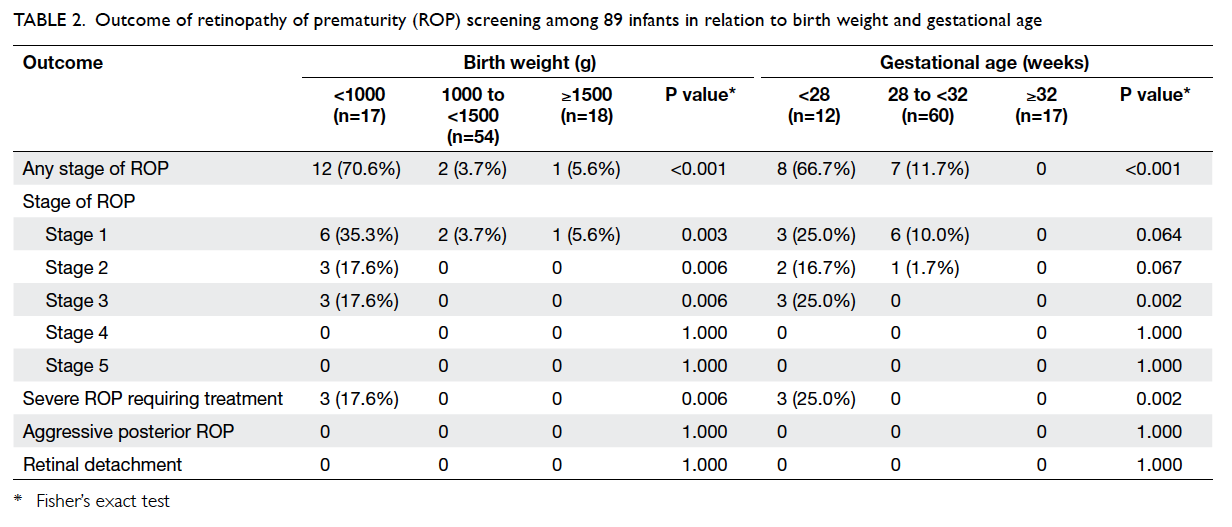

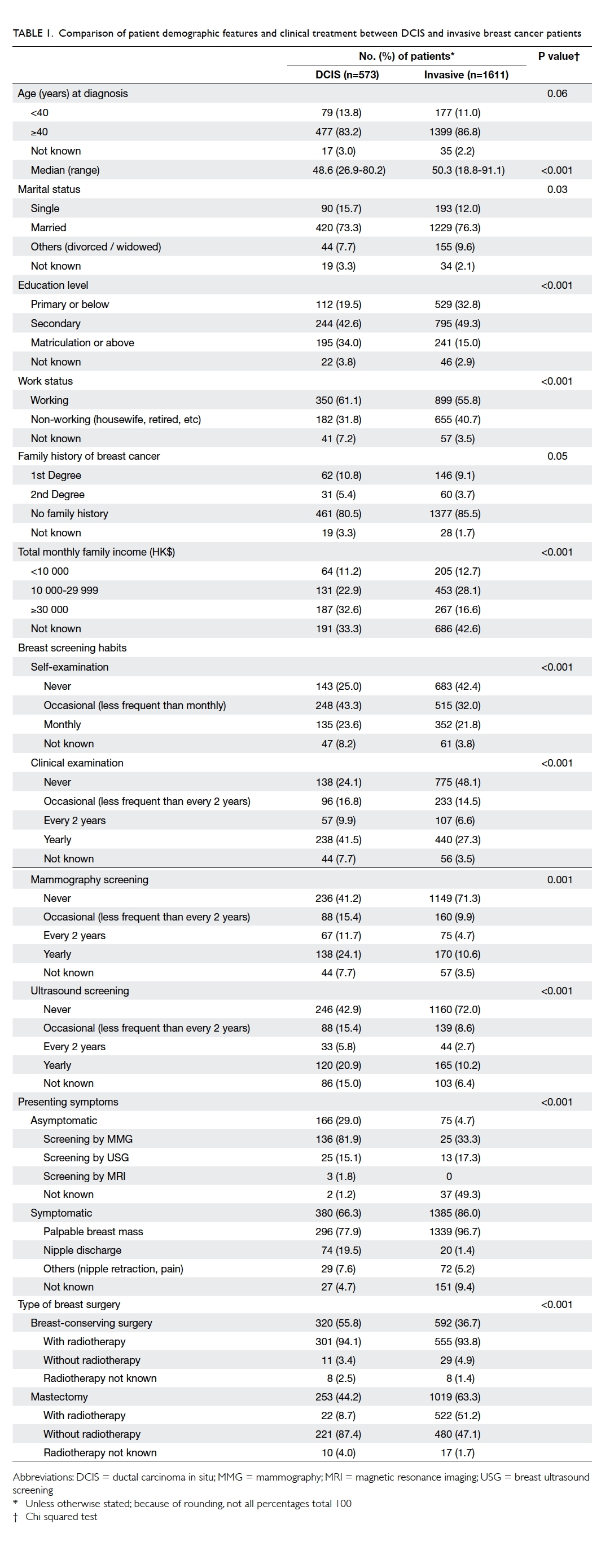

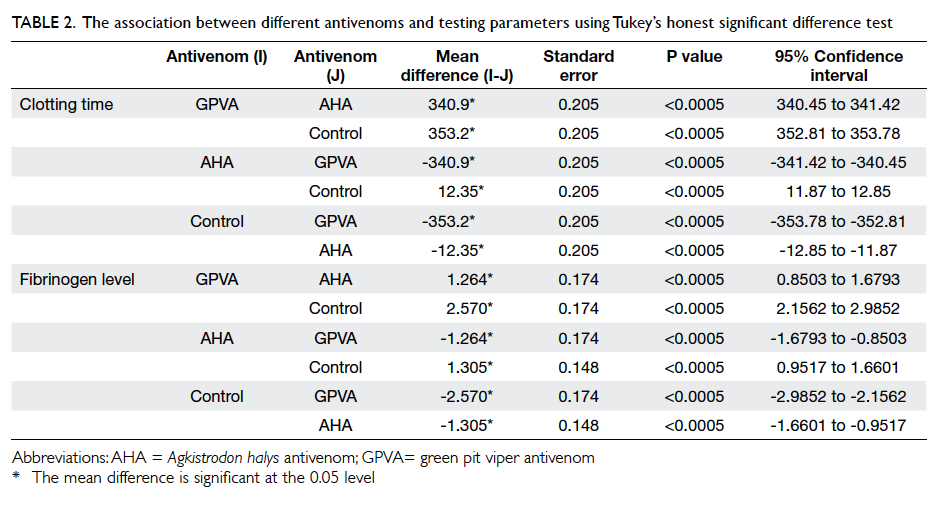

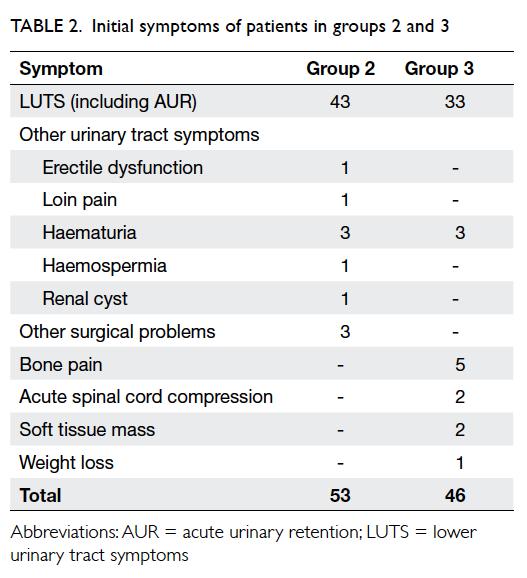

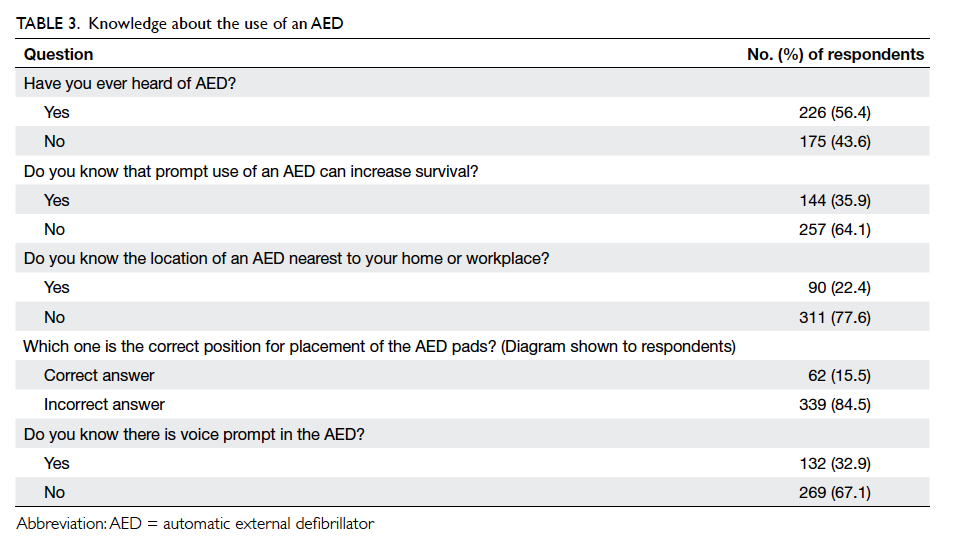

Table 2 presents the haematological and non-haematological

adverse events experienced during

treatment. Grade 3-4 haematological adverse events

included neutropaenia (n=3, 10%), leukopaenia

(1, 3.3%), and anaemia (2, 6.7%). Grade 3-4 non-haematological

adverse events included non-neutropaenic

septic episode (16.7%), diarrhoea

(6.7%), hyperbilirubinaemia (6.7%), syncope (6.7%),

reduced left ventricular ejection function (3.3%),

gouty attack (3.3%), hypokalaemia (3.3%), subacute

intestinal obstruction (3.3%), and urticaria (3.3%).

Of note, 10 patients developed a septic episode;

apart from one patient with grade 3 neutropaenic

fever, the others were non-neutropaenic. Of the

latter, four had grade 3 toxicity, four had grade 2,

and one had grade 1 toxicity; in one patient with

grade 2 toxicity, the infection was due to pulmonary

tuberculosis. This latter patient had a history of

ischaemic heart disease and he also developed grade

3 reduced left ventricular ejection function whilst on

S-1, as noted above.

Two out of 30 patients were found to be

positive for hepatitis B surface antigen. Of these two,

one was prescribed prophylactic antiviral therapy

and liver function remained normal apart from one

isolated episode of grade 2 hyperbilirubinaemia

that resolved spontaneously without other hepatic

dysfunction; the other patient did not receive

prophylactic antiviral therapy but his liver function

remained normal throughout S-1 therapy.

There were no treatment-related deaths.

Dose interruptions

Of the 30 patients, 17 (56.7%) were commenced on

a lower-than-intended dose of S-1. The reason for

reducing the first dose was: impaired renal function

(n=6; with creatinine clearance ranging from 41-48

mL/min), concern of toxicity (6), aged over 70

years (4), and borderline performance status (1);

four of these patients had further dose reduction in

subsequent cycles. Of the other 13 patients who had

the full S-1 dose in cycle 1, five had a dose reduction

from cycle 2 onwards.

Dose delays occurred in 12 (40%) patients;

these were due to delayed bone marrow recovery

(n=3), hypokalaemia (2, including 1 who also had delayed bone marrow recovery), diarrhoea (2), sepsis (2),

hypoglycaemia (1), impaired renal function (1),

reduced weight (1), and abdominal pain (1).

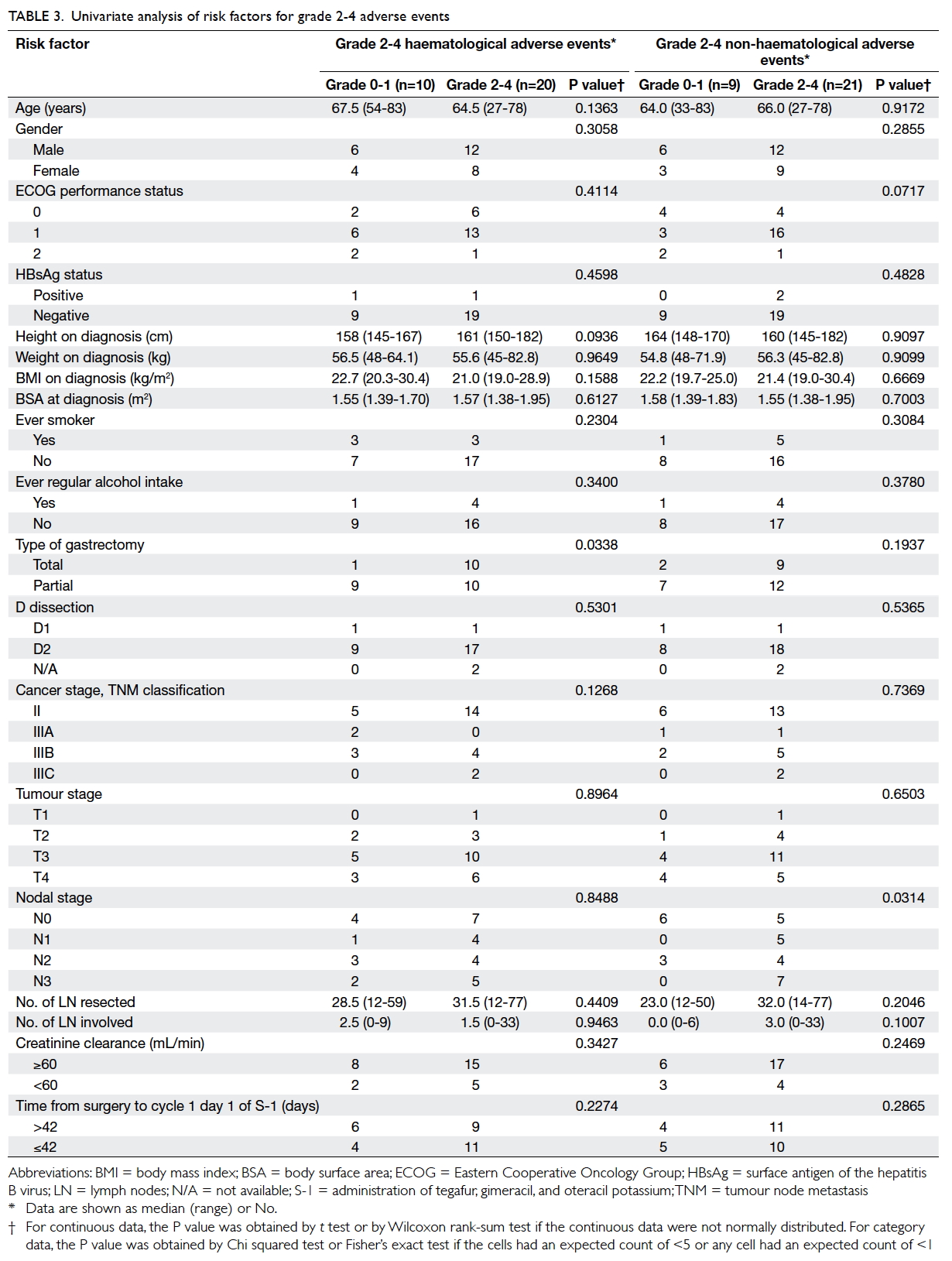

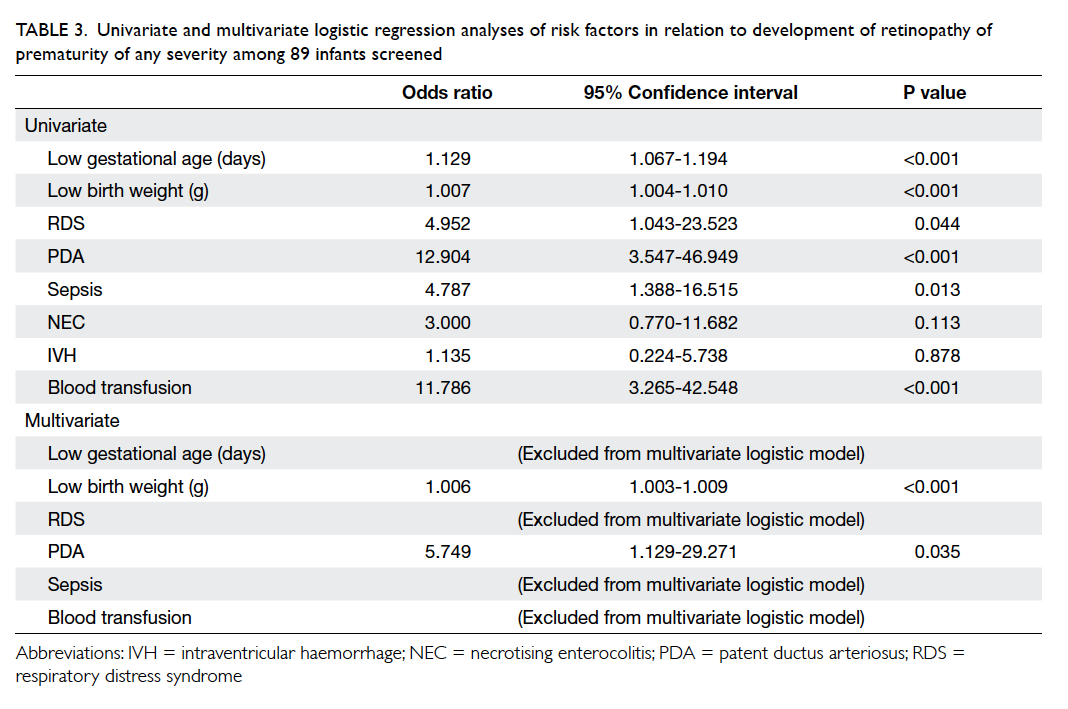

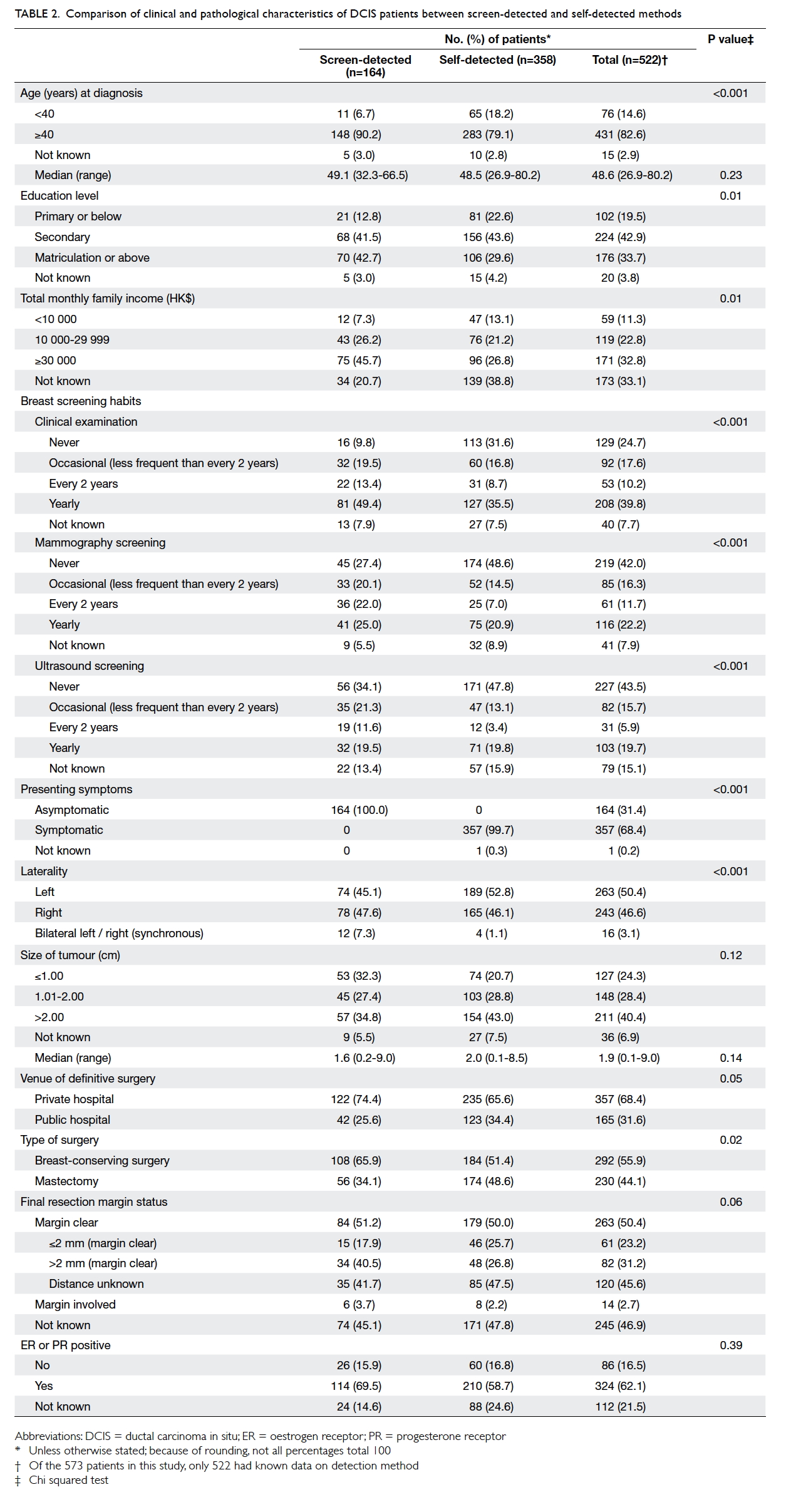

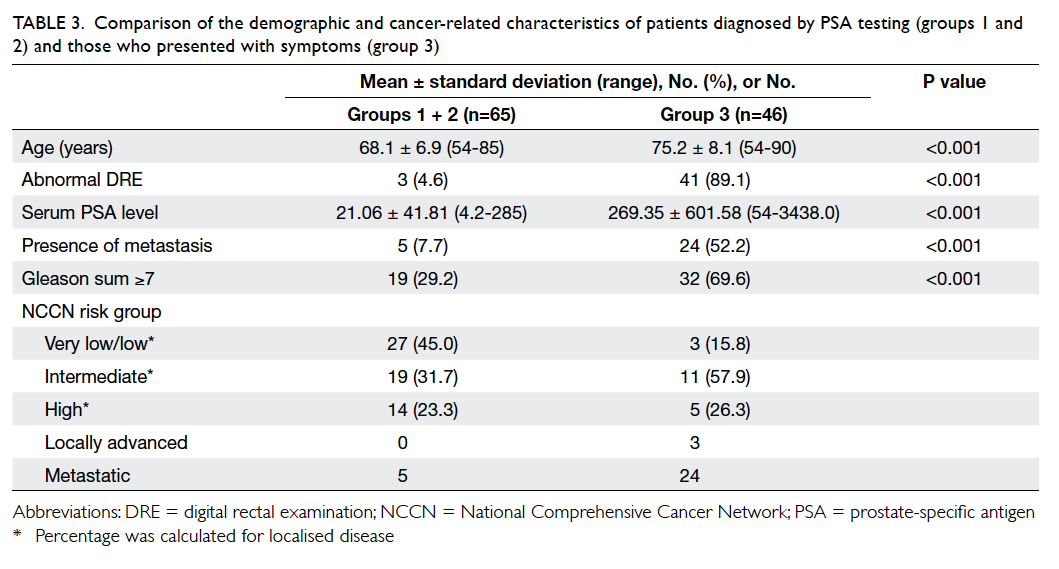

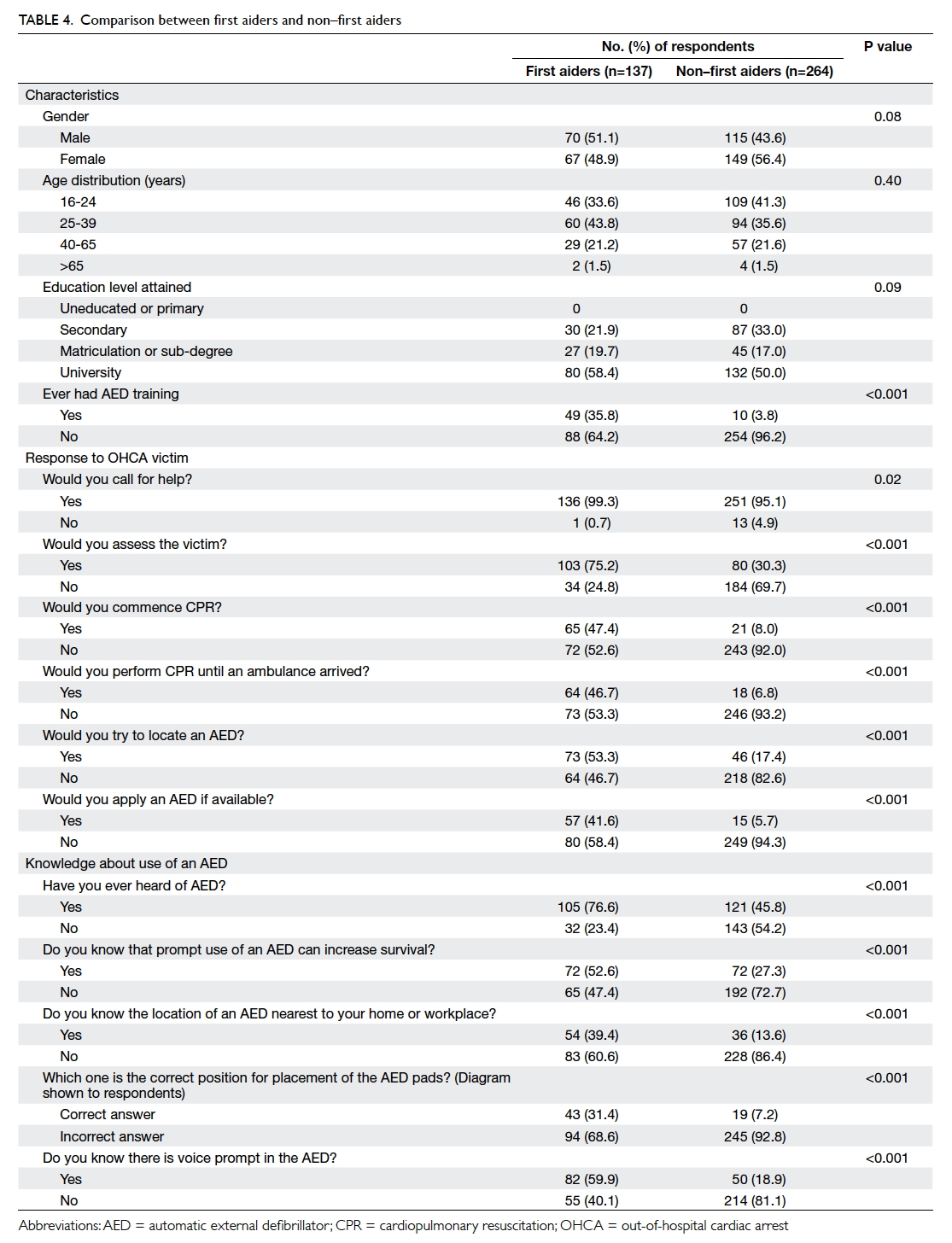

Risk factor analysis

Potential risk factors for adverse events were

assessed (Table 3). Univariate analysis showed that total gastrectomy was significantly associated with

haematological adverse events; 90.9% of patients

who had total gastrectomy in contrast to 52.6% of the

patients who had partial gastrectomy experienced

grade 2-4 adverse events (P=0.034). On univariate

analysis, nodal status was significantly associated

with non-haematological adverse events; 76.2% of

patients who experienced grade 2-4 adverse events

had nodal disease, while only 33% of those who

had grade 0-1 adverse events had nodal disease

(P=0.031).

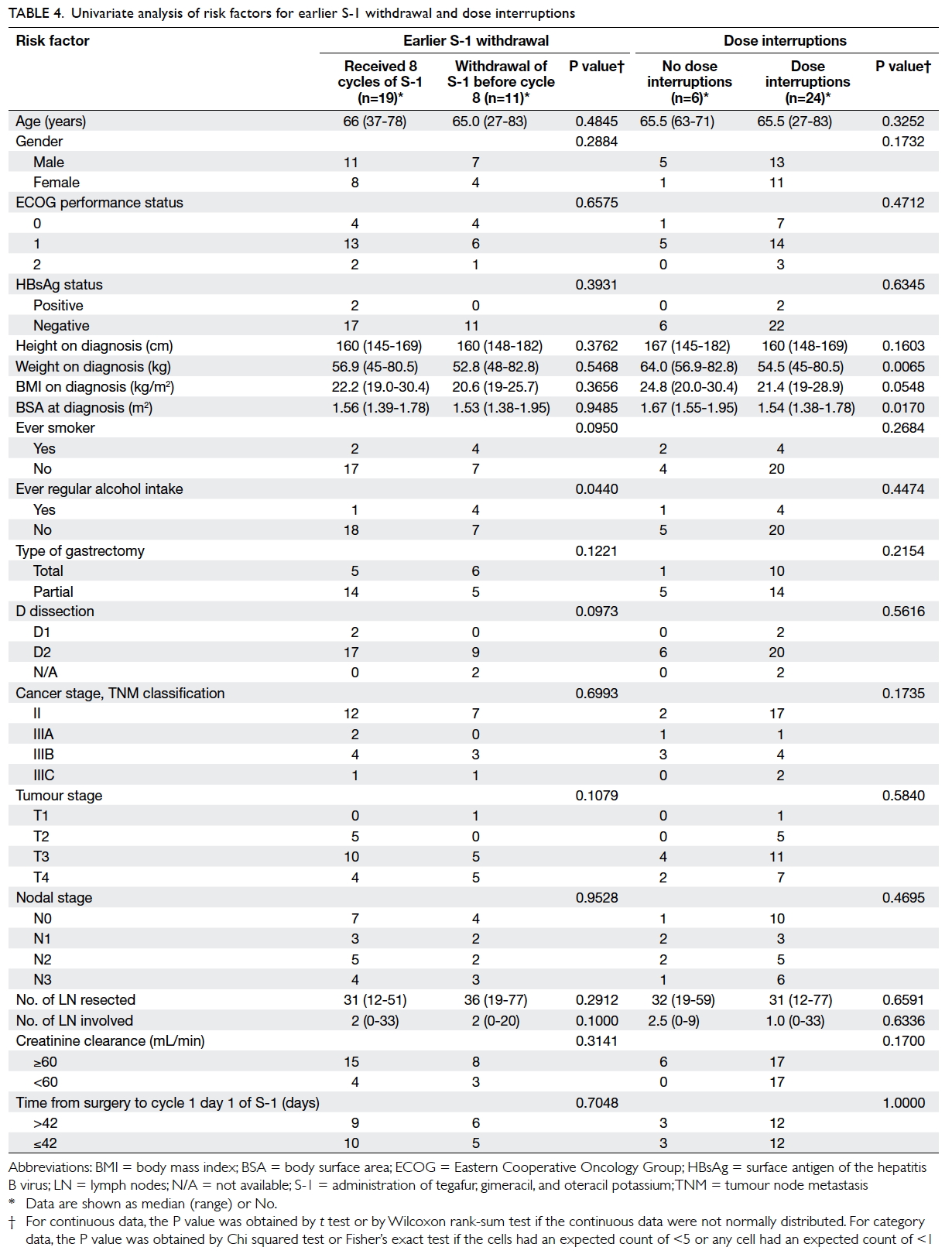

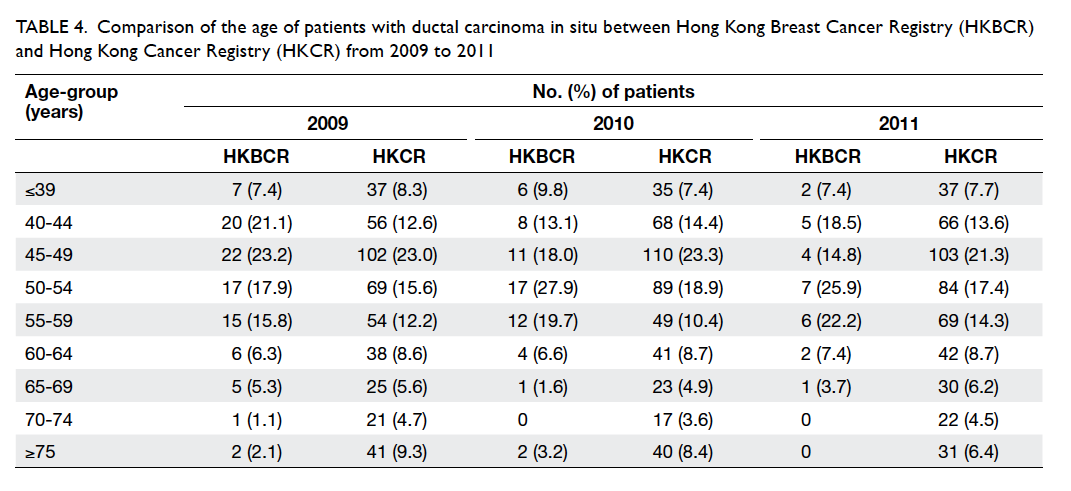

Potential risk factors for earlier withdrawal

of S-1 and dose interruptions (dose reductions

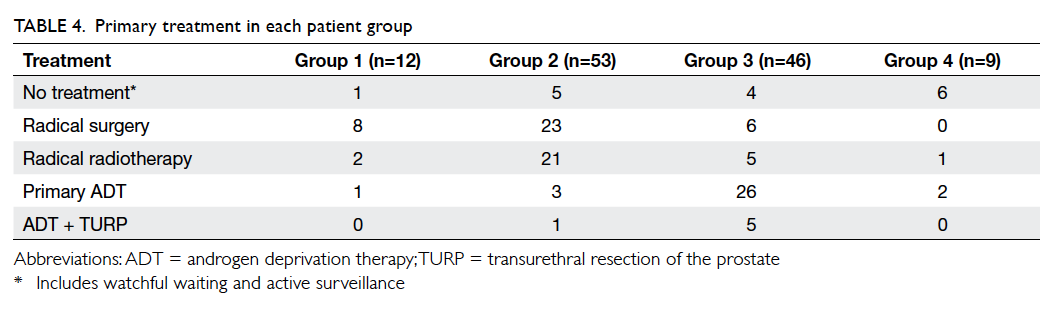

and/or dose delays) were assessed (Table 4). For earlier S-1 withdrawal, patients who had a history

of regular alcohol intake were significantly more

likely to have earlier treatment withdrawal than

non-drinkers (80% vs 28%; P=0.044), while ever-smokers

also had a tendency, though insignificant, for earlier withdrawal

than never-smokers (67% vs 29%; P=0.095). For dose

interruptions, univariate analysis showed lower

body weight (P=0.007) and lower BSA (P=0.017)

were significant associated factors, while lower body

mass index (BMI) also had an increased tendency, though insignificant,

for dose interruptions (P=0.055). The median body

weight, BMI, and BSA of those patients who had dose

interruptions were 54.5 kg, 21.4 kg/m2, and 1.54 m2,

respectively; the corresponding data for those

who did not require dose interruptions were 64.0 kg,

24.8 kg/m2, and 1.67 m2, respectively.

Discussion

Our study results indicate that adjuvant S-1

chemotherapy is feasible for our local patients after

curative resection of gastric cancer. With increased

awareness of the associated toxicity, S-1 can be

offered safely as standard adjuvant therapy. The

toxicities experienced by the studied patients were

in line with previous findings in Asian patients.4 12 13

Grade 3-4 haematological adverse events included

thrombocytopaenia and anaemia. Grade 3-4 non-haematological

adverse events that occurred in 5%

or more of the patients included non-neutropaenic

septic episode, diarrhoea, hyperbilirubinaemia, and

syncope.

Previous studies have investigated factors

associated with adverse events during S-1 therapy.

In a Korean study of 305 patients given adjuvant S-1

therapy,13 total gastrectomy was reported to be an

independent risk factor for grade 3-4 haematological

toxicities and age >65 years was an independent risk

factor for grade 3 non-haematological toxicities.

Independent risk factors for withdrawal and dose

reductions included age >65 years and male gender.

Total gastrectomy has also been reported to be

associated with a significantly greater risk of serious

adverse events in another study of Taiwanese gastric

cancer patients receiving adjuvant S-1.14

The reason for the higher incidence of serious

adverse events in patients who underwent total

gastrectomy whilst receiving S-1 treatment is

unknown. In an earlier study, a higher incidence of

adverse reactions was observed among patients who

received S-1 as adjuvant treatment after gastrectomy,

compared with those who had unresectable or

recurrent gastric cancer. The investigators suggested

the limitation in food intake soon after extensive

surgery as a possible cause of exacerbation of adverse

reactions such as anorexia and nausea, and proposed

that a delay in the start of drug administration after

gastrectomy may prevent such adverse events.15 In

another study, Taiwanese patients received palliative

S-1 for advanced gastric cancer at a median initial

dose of 37.0 mg/m2. Twelve patients had single-dosing

pharmacokinetic study on day 1, and seven

took part in a multiple-dosing pharmacokinetic

study on day 28. The results indicated that the

steady-state pharmacokinetics of 5-FU, CDHP

and Oxo could be predicted from single-dose

pharmacokinetic study. Six patients who underwent

gastrectomy had a similar pharmacokinetic profile

to another six patients who did not undergo

gastrectomy.16 Nonetheless, definitive data regarding

the pharmacokinetic profile of S-1 components

in patients who underwent different degrees of

gastrectomy are lacking.

Other factors that have been reported to be

associated with treatment-related adverse events

include low body mass and impaired renal function.16

These were supported by the present study in which

lower body weight, BMI, and BSA were associated

with an increased likelihood of dose interruptions.

Earlier reports have shown that impaired renal

function will reduce CDHP clearance and result in a

prolonged high concentration of 5-FU in plasma, and

thereby lead to more severe myelosuppression.8 17

Although impaired renal function was not identified

as a risk factor for adverse events in this study, it

has to be noted that all patients who had subnormal

creatinine clearance were offered S-1 at lower doses

at treatment initiation; this could have prevented the

occurrence of severe adverse events.

The present study was limited by its

retrospective nature and the limited number

of patients accrued. Although there is a lack of

information about patient co-morbidities, the

current data suggest that patients who had a history

of regular alcohol intake had an increased likelihood

of earlier treatment withdrawal. The survival data

are immature due to short follow-up. The findings,

however, lend support to a published report on the

acceptable toxicity profile and tolerability of S-1 as

adjuvant therapy after curative gastric surgery for

gastric cancer.4 13 14 Potential risk factors for severe

adverse events are suggested. Due to the small

sample size and retrospective nature of this study, a

prospective study with a larger patient population is

needed to confirm these findings. An awareness of

treatment-related adverse events as well as potential

associated factors may aid clinicians in managing

patients in whom S-1 therapy is planned, and

thereby improve treatment compliance and clinical

outcome.

Conclusions

Adjuvant S-1 therapy has a tolerable toxicity profile

among local patients who have undergone curative

resection for gastric cancer. For gastric cancer

patients in whom adjuvant S-1 therapy is planned,

those with identifiable risk factors should be closely

monitored for adverse events during treatment. This

may enable earlier intervention with supportive

therapy and optimise treatment outcome.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Mr Edward Choi

for his valuable statistical advice. We thank Drs Chi-ching

Law, Hoi-leung Leung, and Chung-kong Kwan

of the Department of Clinical Oncology, United

Christian Hospital for their support in this study.

Declaration

This study has been supported by an educational

grant from Taiho Pharma Singapore Pte. Ltd. W

Yeo has received honorarium for advisory role for

Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Bristol Myers Squibb

and has received research grant from Novartis over

the past 12 months. KO Lam has been an advisor

for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and has

received honorarium from Amgen, Bayer, Eli Lilly,

Merck, Sanofi-Aventis, Taiho and research grant

from Bayer, Roche, and Taiho. Authors not named

here have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin

DM. GLOBOCAN 2008: Cancer incidence and mortality

worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10. Lyon, France:

International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.

Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 12 Oct

2011.

2. Gallo A, Cha C. Updates on esophageal and gastric cancers.

World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:3237-42. Crossref

3. GASTRIC (Global Advanced/Adjuvant Stomach Tumor

Research International Collaboration) Group, Paoletti

X, Oba K, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy

for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA

2010;303:1729-37. Crossref

4. Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Adjuvant

chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral

fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1810-20. Crossref

5. Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine

and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy

(CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled

trial. Lancet 2012;379:315-21. Crossref

6. Shirasaka T, Shimamato Y, Ohshimo H, et al. Development

of a novel form of an oral 5-fluorouracil derivative (S-1)

directed to the potentiation of the tumor selective

cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil by two biochemical

modulators. Anticancer Drugs 1996;7:548-57. Crossref

7. Kubota T. The role of S-1 in the treatment of gastric cancer.

Br J Cancer 2008;98:1301-4. Crossref

8. Hirata K, Horikoshi N, Aiba K, et al. Pharmacokinetic

study of S-1, a novel oral fluorouracil antitumor drug. Clin

Cancer Res 1999;5:2000-5.

9. Chu QS, Hammond LA, Schwartz G, et al. Phase I and

pharmacokinetic study of the oral fluoropyrimidine S-1 on

a once-daily-for-28-day schedule in patients with advanced

malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:4913-21. Crossref

10. Ajani JA, Faust J, Ikeda K, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic

study of S-1 plus cisplatin in patients with advanced gastric

carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6957-65. Crossref

11. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL,

Trotti A. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer

Staging Manual. 7th ed. Chicago: Springer; 2010.

12. Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, et al. CTCAE v3.0:

development of a comprehensive grading system for the

adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol

2003;13:176-81. Crossref

13. Jeong JH, Ryu MH, Ryoo BY, et al. Safety and feasibility

of adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 for Korean patients

with curatively resected advanced gastric cancer. Cancer

Chemother Pharmacol 2012;70:523-9. Crossref

14. Chou WC, Chang CL, Liu KH, et al. Total gastrectomy

increases the incidence of grade III and IV toxicities in

patients with gastric cancer receiving adjuvant TS-1

treatment. World J Surg Oncol 2013;11:287. Crossref

15. Kinoshita T, Nashimoto A, Yamamura Y, et al. Feasibility

study of adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 (TS-1; tegafur,

gimeracil, oteracil potassium) for gastric cancer. Gastric

Cancer 2004;7:104-9. Crossref

16. Chen JS, Chao Y, Hsieh RK, et al. A phase II and

pharmacokinetic study of first line S-1 for advanced

gastric cancer in Taiwan. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol

2011;67:1281-9. Crossref

17. Koizumi W, Kurihara M, Nakano S, Hasegawa K. Phase

II study of S-1, a novel oral derivative of 5-fluorouracil, in

advanced gastric cancer. For the S-1 Cooperative Gastric

Cancer Study Group. Oncology 2000;58:191-7. Crossref