Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: initial experience in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Med J 2017 Aug;23(4):349–55 | Epub 28 Jun 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166030

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: initial experience in Hong Kong

Michael KY Lee, MB, BS, FRCP1; SF Chui, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Alan KC Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Jason LK Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Eric CY Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; KT Chan, MB, BS, FRCP1; HL Cheung, MB, ChB, FRCS2; CS Chiang, MB, BS, FRCP1

1 Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Michael KY Lee (kylee1991@hotmail.com)

A video clip showing transcatheter aortic valve implantation technique

A video clip showing transcatheter aortic valve implantation techniqueAbstract

Introduction: Aortic

stenosis is one of the most common valvular heart diseases in

the ageing population. Patients with symptomatic severe aortic

stenosis are at high risk of sudden death. Surgical

aortic-valve replacement is the gold standard of treatment but

many patients do not receive surgery because of advanced age

or co-morbidities. Recently, transcatheter aortic valve

implantation has been developed as an option for these

patients. This study aimed to assess efficacy and safety of

this procedure in the Hong Kong Chinese population.

Methods: Data for baseline patient characteristics,

procedure parameters, and clinical outcomes up to

1-year post-implantation in a regional hospital in

Hong Kong were collected and analysed.

Results: A total of 56 patients with severe aortic

stenosis underwent the procedure from December

2010 to September 2015. Their mean (± standard

deviation) age was 81.9 ± 4.8 years; 64.3% of them

were male. Their mean logistic EuroSCORE was

22.6% ± 13.4%. After implantation, the mean aortic

valve area improved from 0.70 cm2 ± 0.19 cm2 to 1.94 cm2 ± 0.37 cm2. Of the patients, 92%

were improved by at least one New York Heart

Association functional class. Stroke and major

vascular complications occurred in one (1.8%) and five (8.9%) patients, respectively. A permanent

pacemaker was implanted in seven (12.5%) patients.

Both hospital and 30-day mortalities were 1.8%.

The 1-year all-cause and cardiovascular mortality

rates were 12.5% and 7.1%, respectively.

Conclusions: Transcatheter aortic valve

implantation has been developed as an alternative

treatment for patients with symptomatic severe

aortic stenosis who are deemed inoperable or high

risk for surgery. Our results are very promising and

comparable with those of major clinical trials.

New knowledge added by this study

- Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is safe and feasible in patients with symptomatic severe aortic valve stenosis and high surgical risk.

- Clinical outcome was very promising for up to 1 year in patients who underwent TAVI.

- TAVI should be offered to patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis who are deemed inoperable or at high risk for open heart surgery.

Introduction

With improved living standards and advances in

medical treatment, the respective life expectancies

of males and females in Hong Kong have increased

from 72.3 years and 78.5 years in 1981, to 81.2 years

and 86.7 years in 2014.1 Aortic stenosis is one of the

most common valvular heart diseases in the ageing

population.2 The prevalence of aortic stenosis is up

to 4.6% in people older than 75 years.2 After onset of

symptoms, including the classic triad of chest pain,

heart failure or syncope, patients with severe aortic

stenosis are at very high risk of sudden death with

2-year mortality rate of up to 50% if left untreated.3 4 5 Surgical aortic-valve replacement (SAVR) is the gold

standard of treatment for patients with symptomatic

severe aortic stenosis.3 4 6 7 Many do not receive

surgical treatment, however, because of advanced

age or multiple co-morbidities.8 Transcatheter

aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has recently been

developed as an option for these patients who are

inoperable or at high risk of SAVR.9 10

Queen Elizabeth Hospital is the first hospital

in Hong Kong to perform TAVI since December

2010. This study aimed to assess the efficacy and

safety of this procedure in the Hong Kong Chinese

population.

Methods

In order to introduce TAVI into Hong Kong, a

Structural Heart Team comprising cardiologists,

cardiac surgeons, cardiac anaesthesiologists,

radiologists and cardiac nurses, was formed in early

2010 in Queen Elizabeth Hospital, which is a regional

hospital in Hong Kong. All potential patients

were assessed and interviewed independently

by cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. Clinical

assessment of functional status, transthoracic

echocardiogram, transoesophageal echocardiogram

(TEE), computed tomographic (CT) scan, and

conventional angiogram were performed according

to the protocol to assess the risks of SAVR and

suitability for TAVI. The Structural Heart Team

would undertake these investigations to assess

whether the risks of the patients were too high for

SAVR and if they were suitable for TAVI.

The correct size of the TAVI device was based

on the aortic annular dimensions measured by

TEE and CT scan. The preferred route of device

introduction was via the femoral artery. Based

on findings such as the vessel diameter, degree of

calcification and tortuosity found on CT imaging,

the subclavian artery or direct aortic approach was

also a valid alternative. The device was implanted

under fluoroscopic guidance and the correct

position monitored by fluoroscopy and TEE. Patients

underwent transthoracic echocardiogram prior

to discharge to assess device function and exclude

pericardial effusion. Post-discharge, regular clinic

visits, and serial transthoracic echocardiograms

were arranged to assess progress and monitor any

adverse events. All complications were reported to

an independent Safety Monitoring Committee of the

hospital.

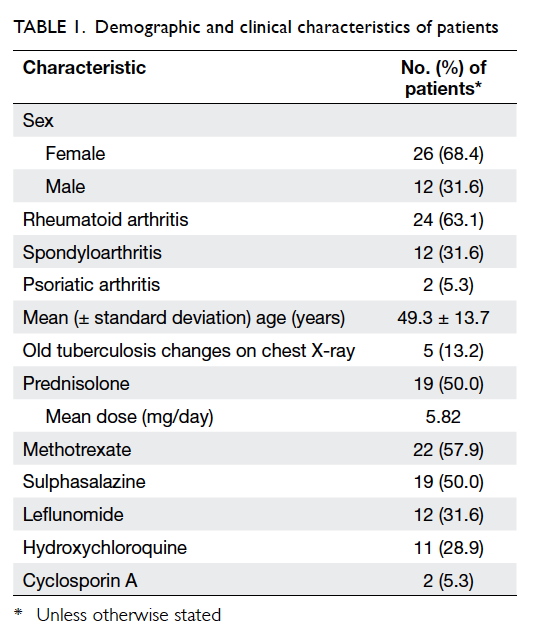

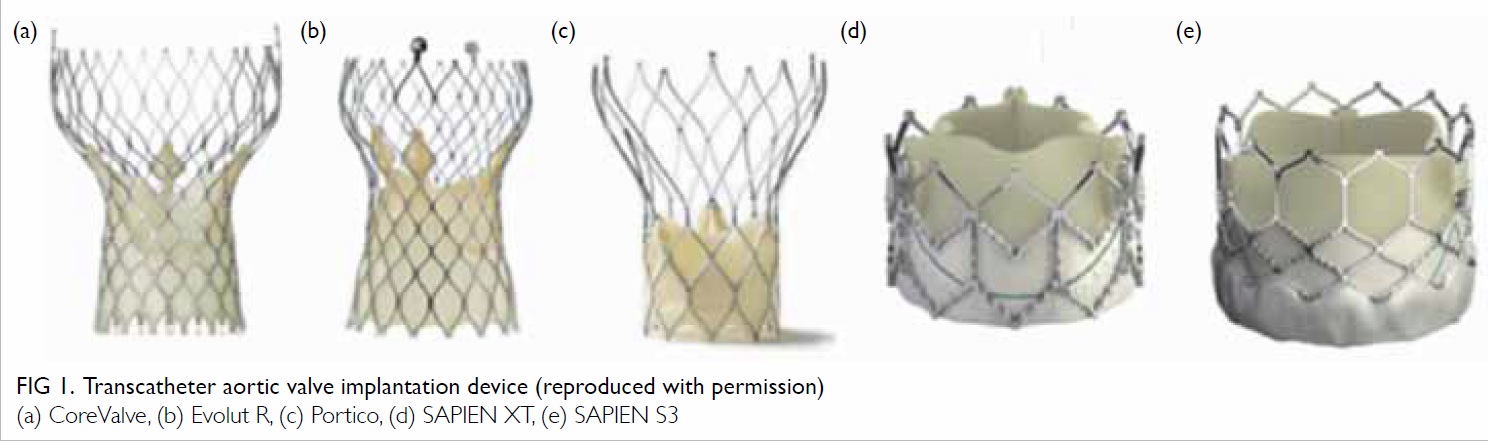

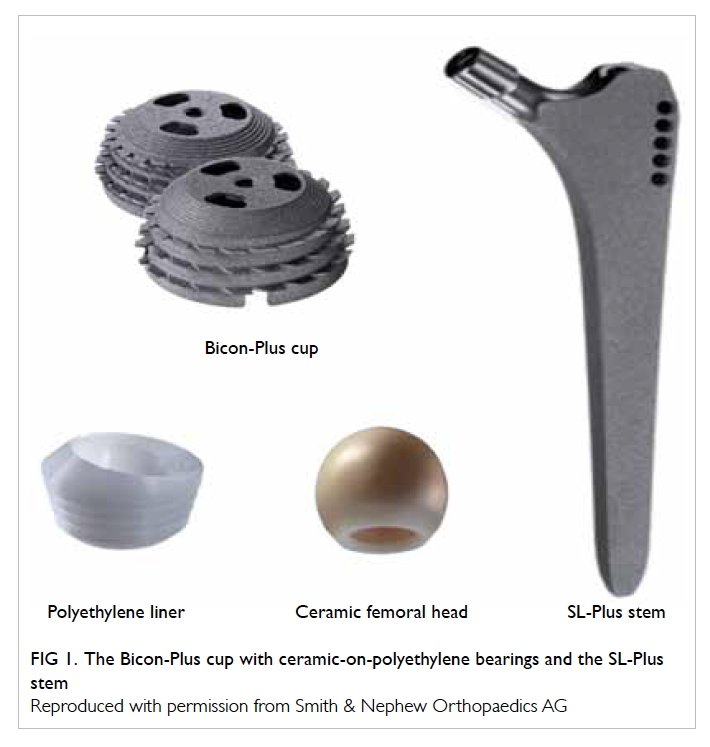

The first TAVI device was used in December

2010 and was a self-expanding Medtronic CoreValve

device (Medtronic, Minneapolis [MN], US) [Fig 1a]. Subsequent to the introduction of its second-generation

Evolut R (Medtronic, Minneapolis [MN],

US) in 2015 (Fig 1b), it was used in most cases due

to its improved design of recapture/repositioning

ability and its smaller sheath size (18 Fr vs 14 Fr).

We obtained another self-expanding device with

recapture/repositioning ability (St Jude Medical

Portico; St Jude Medical, Minneapolis [MN], US;

Fig 1c), and a balloon-expandable device (Edwards

SAPIEN XT; Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine [CA], US) [Figs 1d and 1e] in 2015. This enhanced the ability to

treat a broad spectrum of patients with a wide variety

of clinical and anatomical challenges. The choice of

valve type was made by the Structural Heart Team,

based on the anatomy of the native aortic valve, size,

and calcification of iliofemoral vessels and need for

alternative access.

Figure 1. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation device (reproduced with permission)

(a) CoreValve, (b) Evolut R, (c) Portico, (d) SAPIEN XT, (e) SAPIEN S3

All patients who underwent TAVI during the

study period were entered into the TAVI registry

of our hospital. Their baseline characteristics,

procedural details, device used, and clinical

outcomes were recorded. They attended for regular

follow-up in our structural heart disease clinic as well

as regular echocardiographic monitoring. Follow-up

data were also added to the registry. Any patient who

defaulted follow-up was contacted; if they had died,

cause of death was retrieved from their electronic

patient record of Hospital Authority of Hong

Kong.

We retrieved and analysed the data of the

TAVI registry. Descriptive statistics were used to

report baseline characteristics, procedural results,

and clinical outcomes. Analysis was performed

using the Microsoft Office Excel (Mac version 2011;

Microsoft, Washington, US). The study was performed in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Baseline characteristics

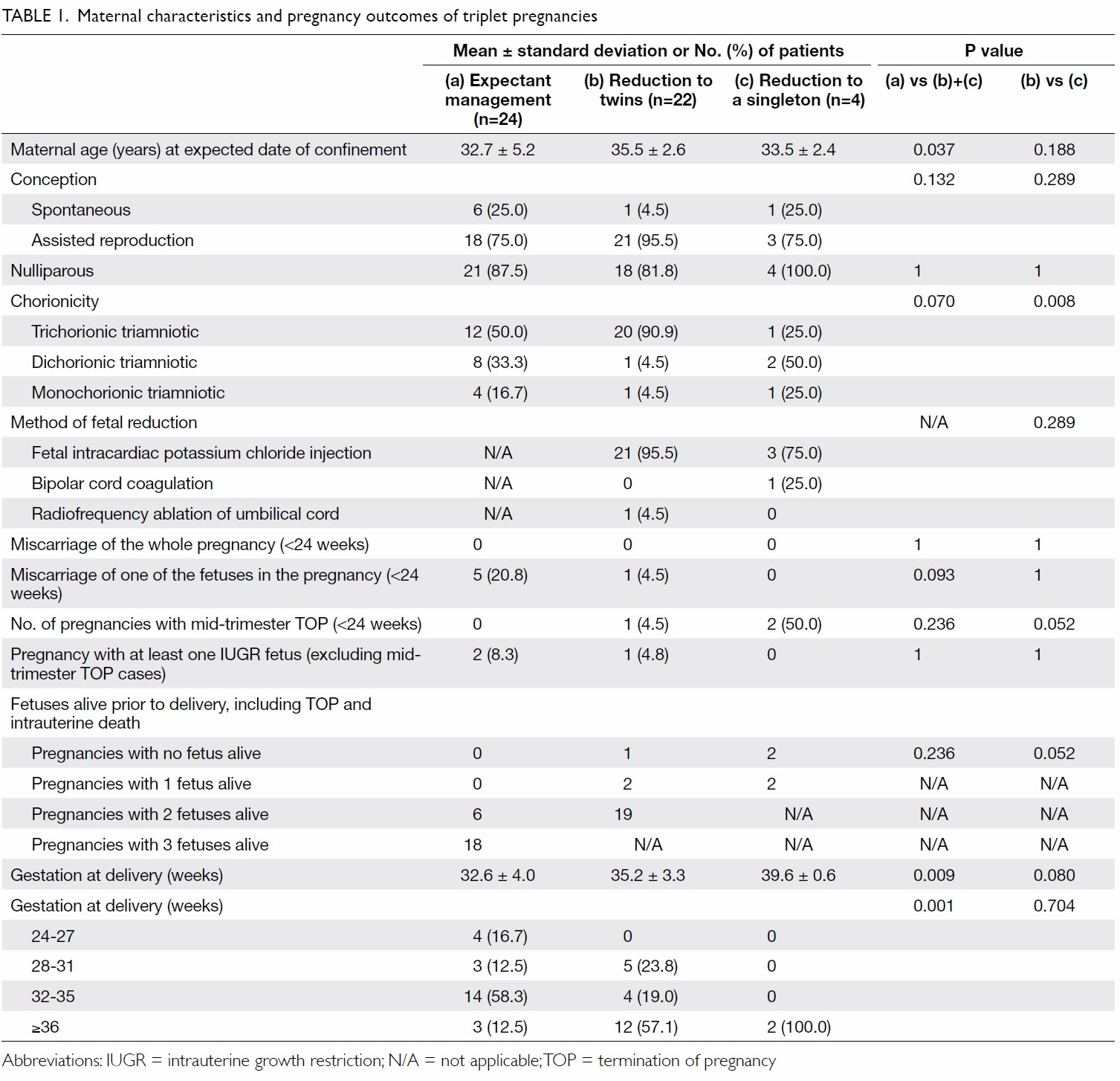

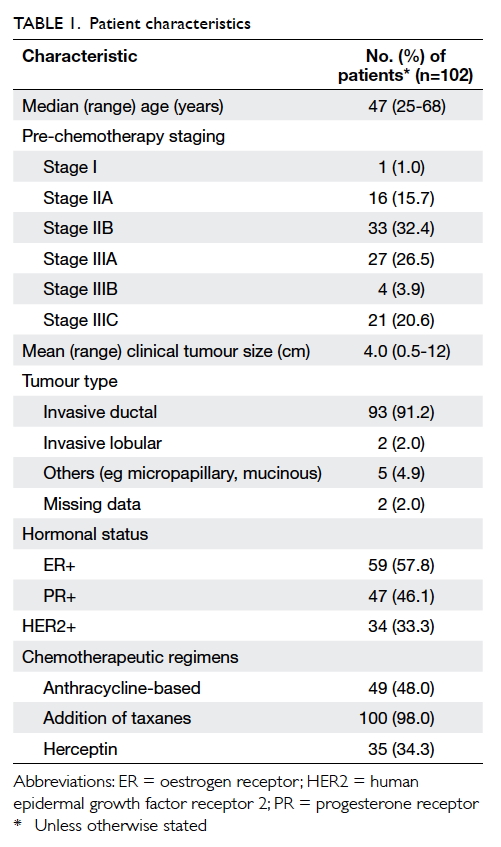

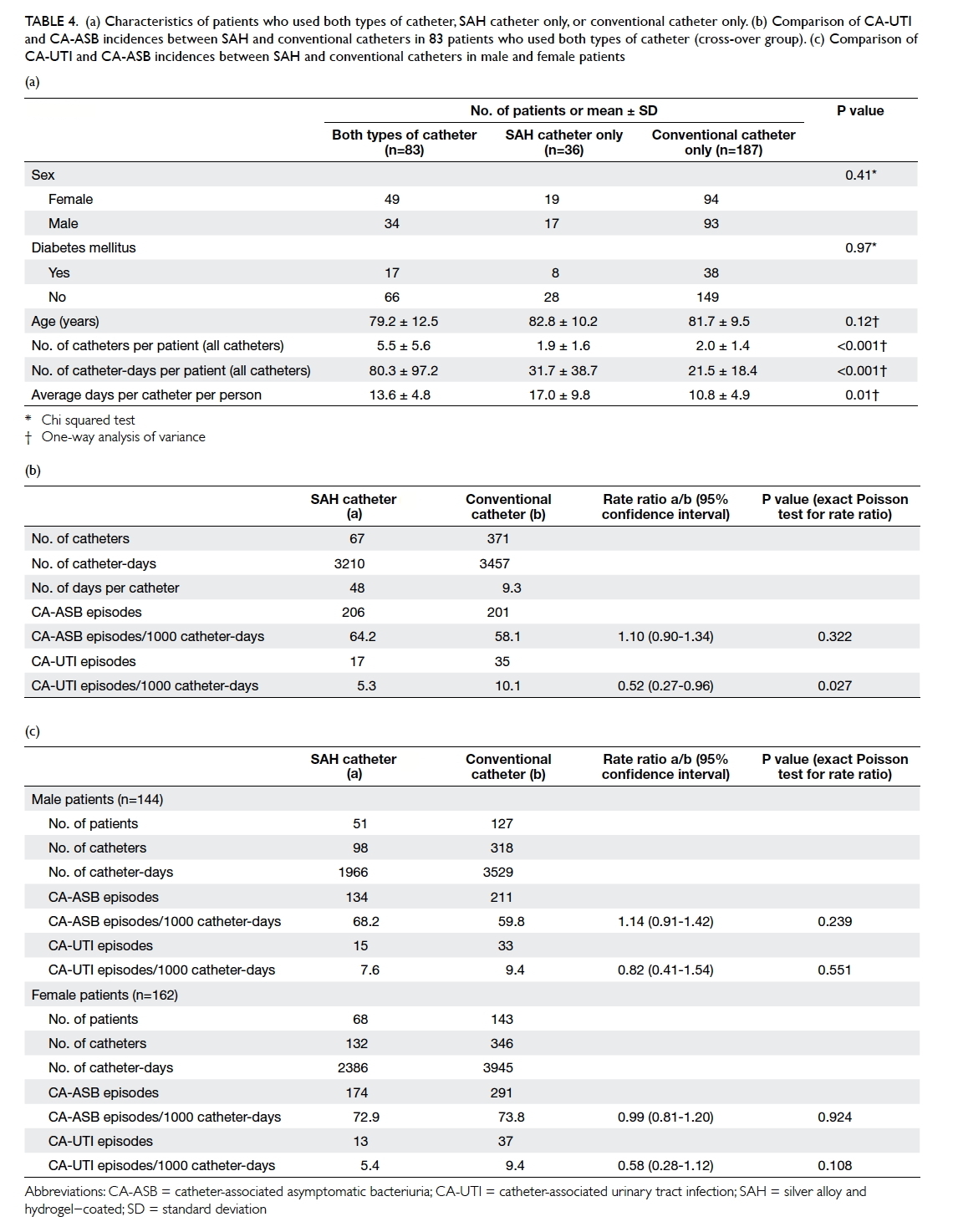

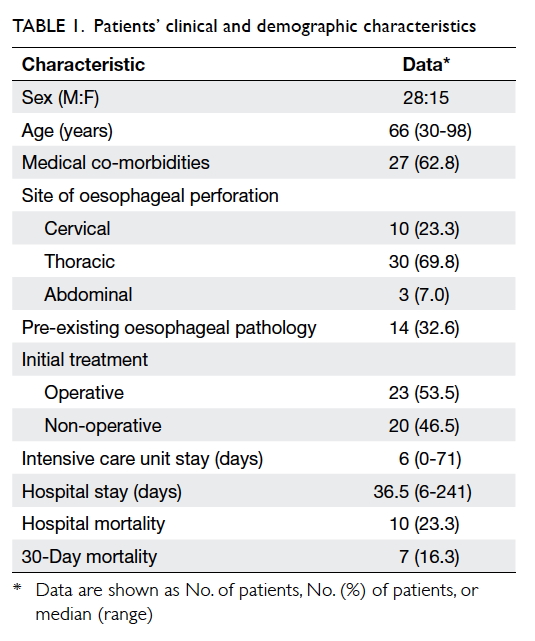

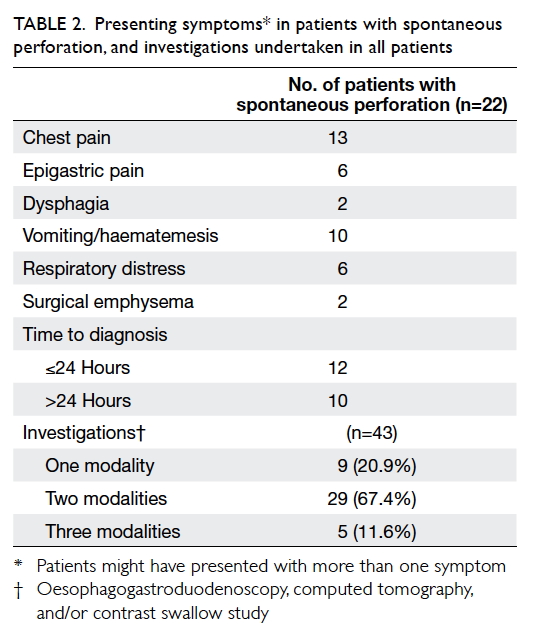

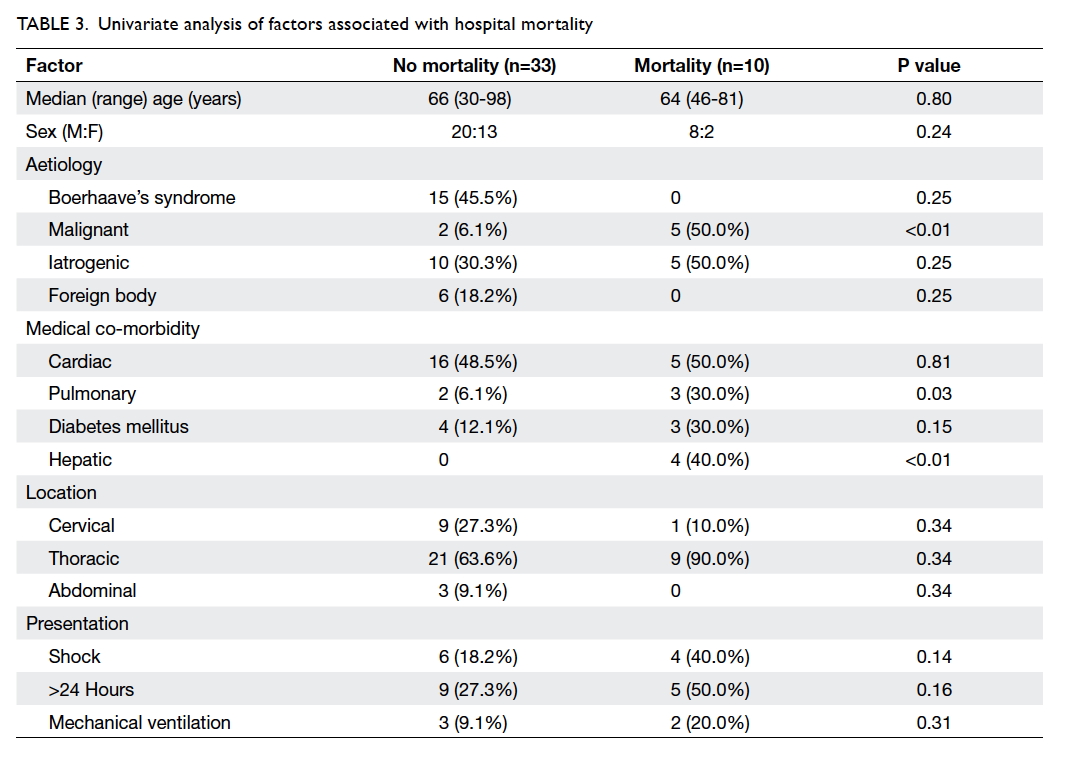

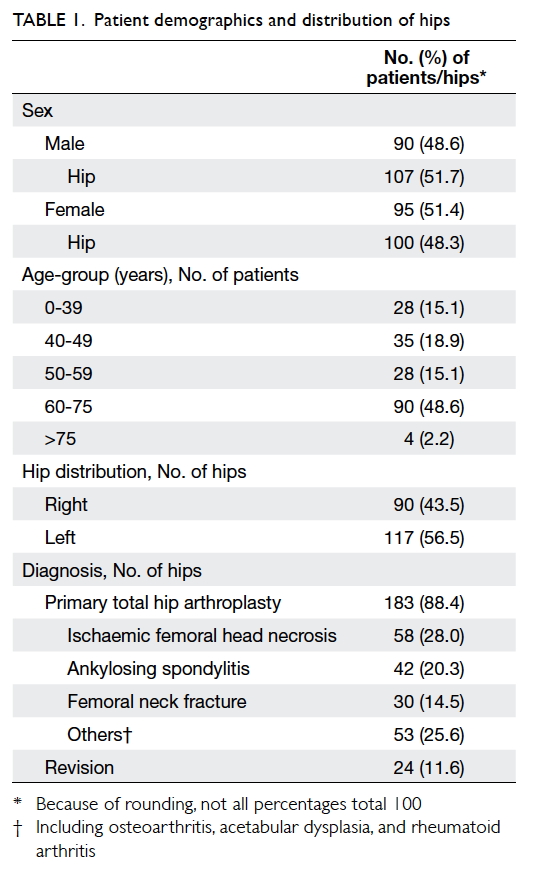

From December 2010 to September 2015, a total of

56 patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis

underwent TAVI. Their baseline characteristics are

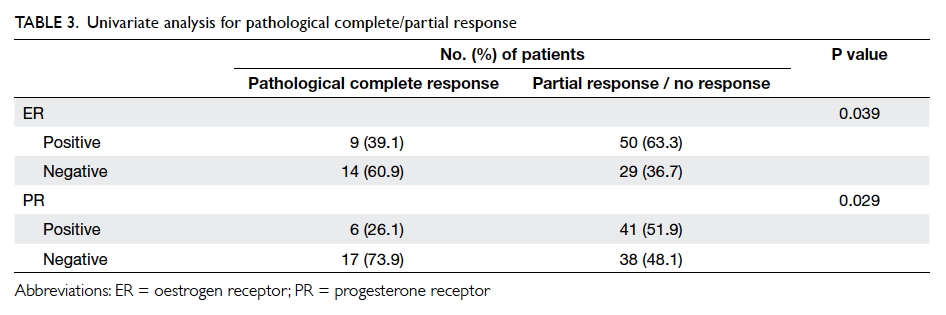

outlined in Table 1. Their mean (± standard deviation)

age was 81.9 ± 4.8 years, and the majority (64.3%) were male. The prevalence of severe co-morbidities was

predicted as high, with a mean logistic EuroSCORE

of 22.6% ± 13.4% and a mean Society of Thoracic

Surgeons score of 7.0 ± 4.4. Several variables were

taken into account when calculating these risk scores,

such as age, symptoms at presentation, current

haemodynamic status, left ventricular systolic

function, baseline renal function, New York Heart

Association (NYHA) functional class, and presence

of other co-morbidities such as peripheral artery

disease, pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular

disease. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction

(LVEF) was 54.8% ± 12.9%. Most patients had

various degrees of heart failure symptoms with 22

(39.3%), 26 (46.4%), and six (10.7%) patients in NYHA

class II, III, and IV, respectively. All patients had

severe aortic stenosis on echocardiography, defined

by standard criteria with a mean aortic valve area

of 0.7 cm2 ± 0.2 cm2 and mean aortic transvalvular pressure gradient of 49.0 mm Hg ± 12.9 mm Hg.

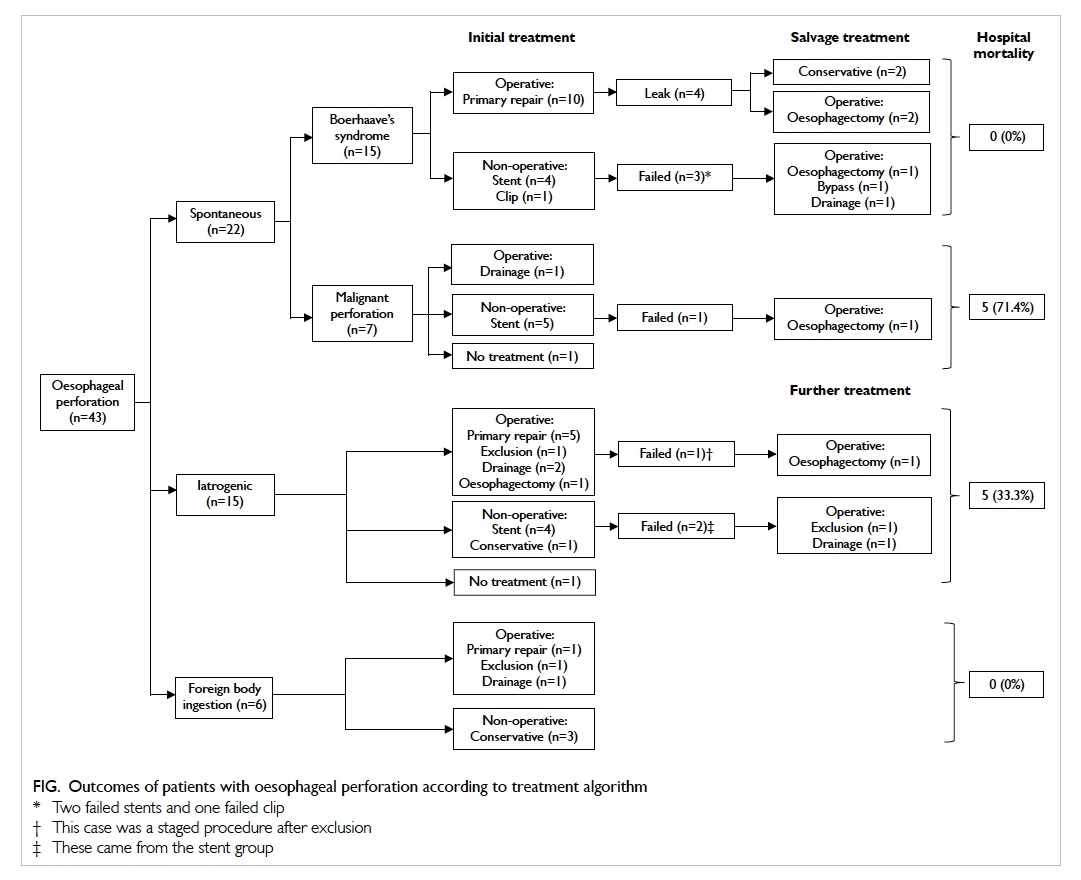

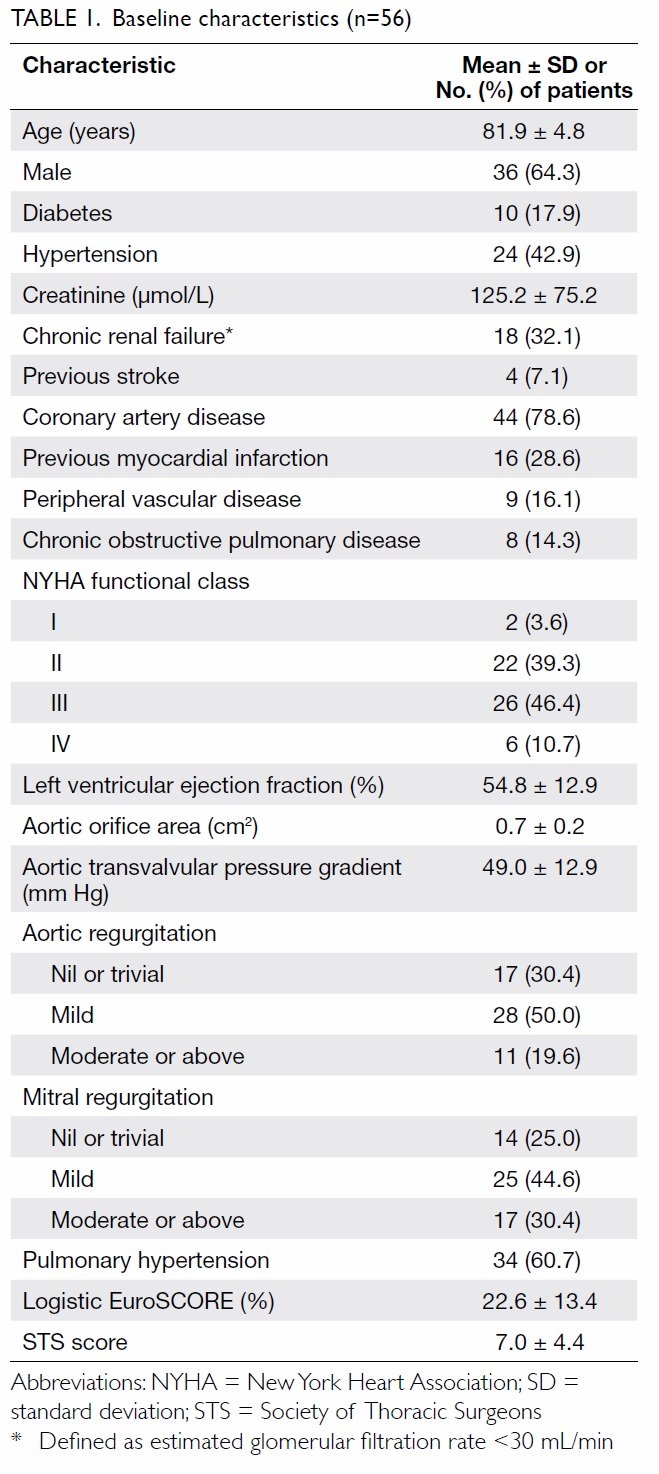

Procedural outcomes

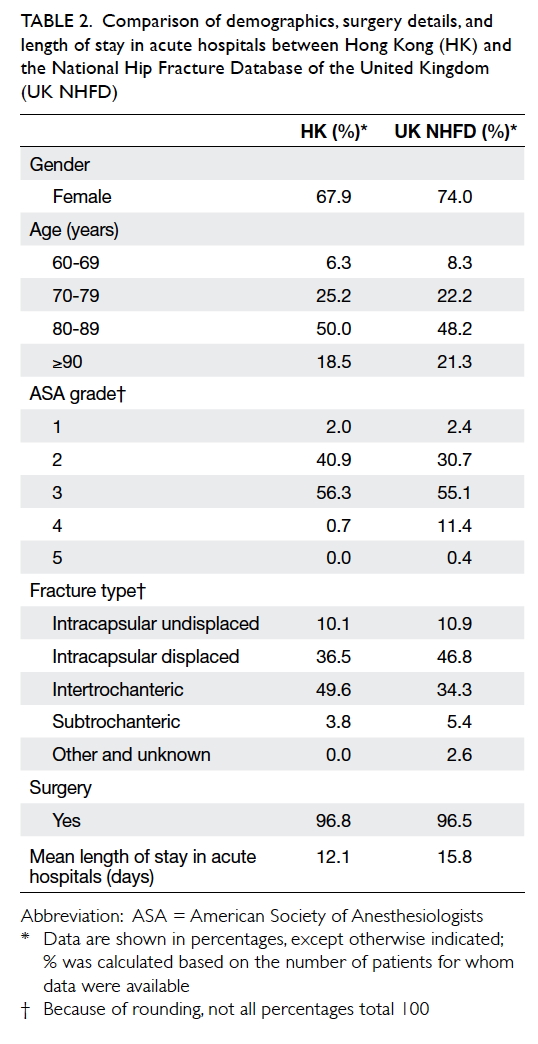

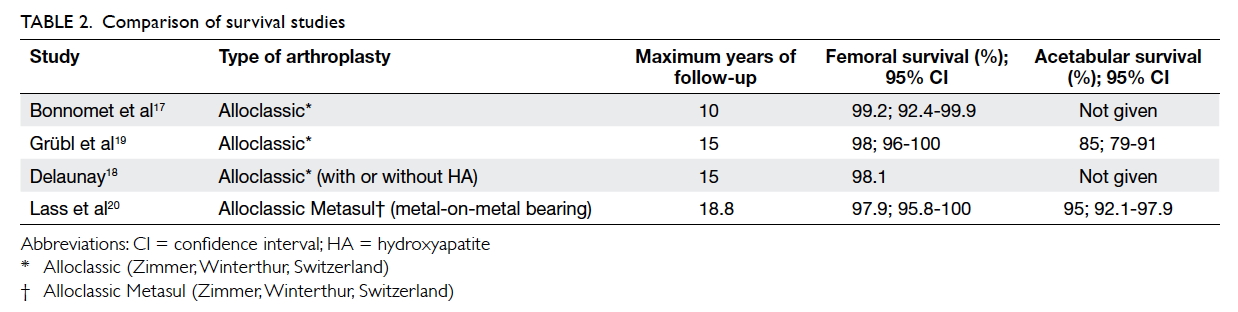

The procedural outcomes are summarised in Table 2. Successful implantation was completed in 98.2% of patients and all procedures were performed

under general anaesthesia. Transfemoral access

was successful in most cases (54 patients, 96.4%)

although one (1.8%) patient was treated via the

subclavian approach and one (1.8%) via a direct

aortic approach. The most commonly used TAVI

device was a 26-mm prosthesis. A second valve was

required during the index procedure in nine (16.1%)

patients due to suboptimal position of the first

device. Most patients (32/56, 57.1%) had no or

trivial aortic regurgitation following implantation

and 23 (41.1%) had mild aortic regurgitation. None

had moderate or severe aortic regurgitation.

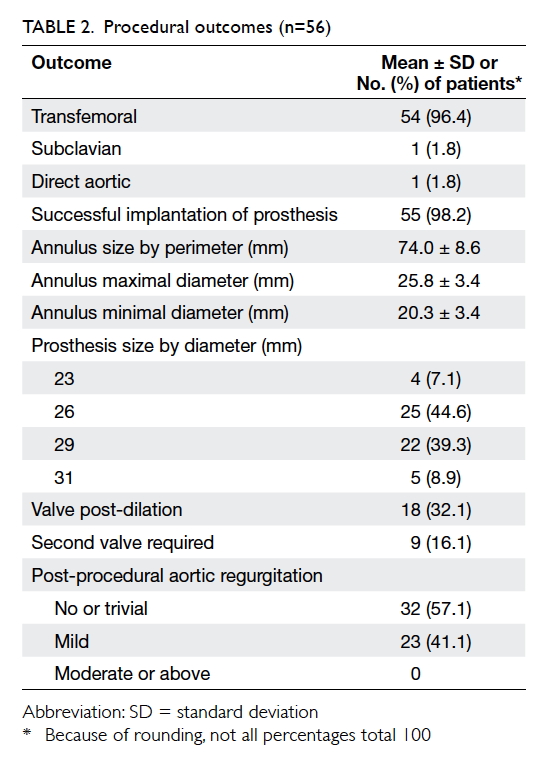

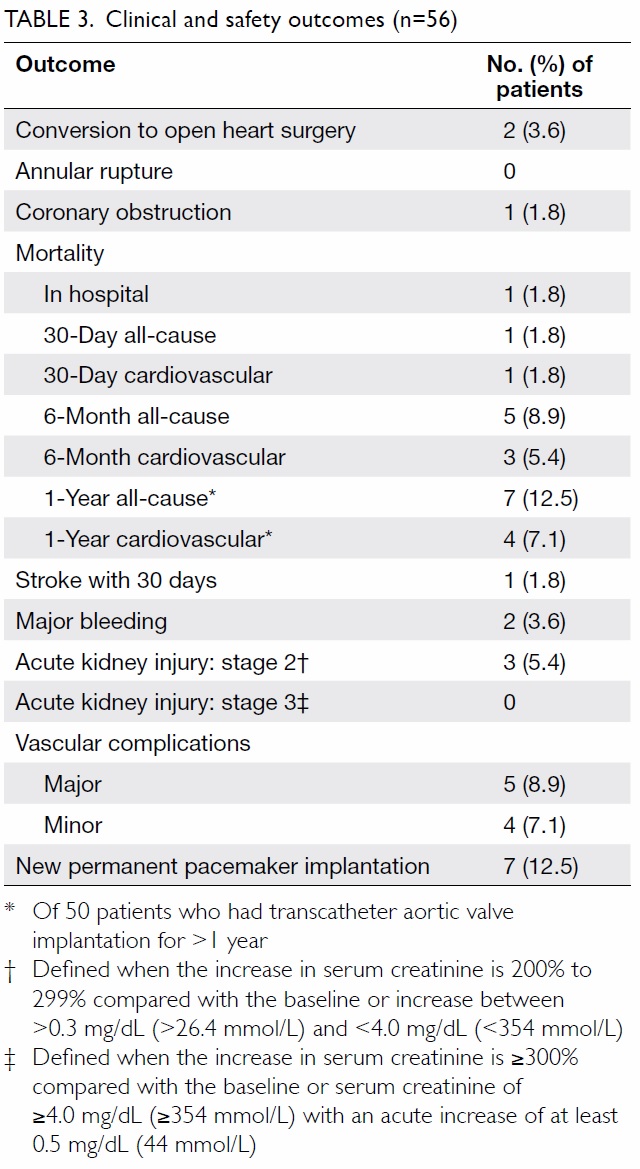

Adverse events

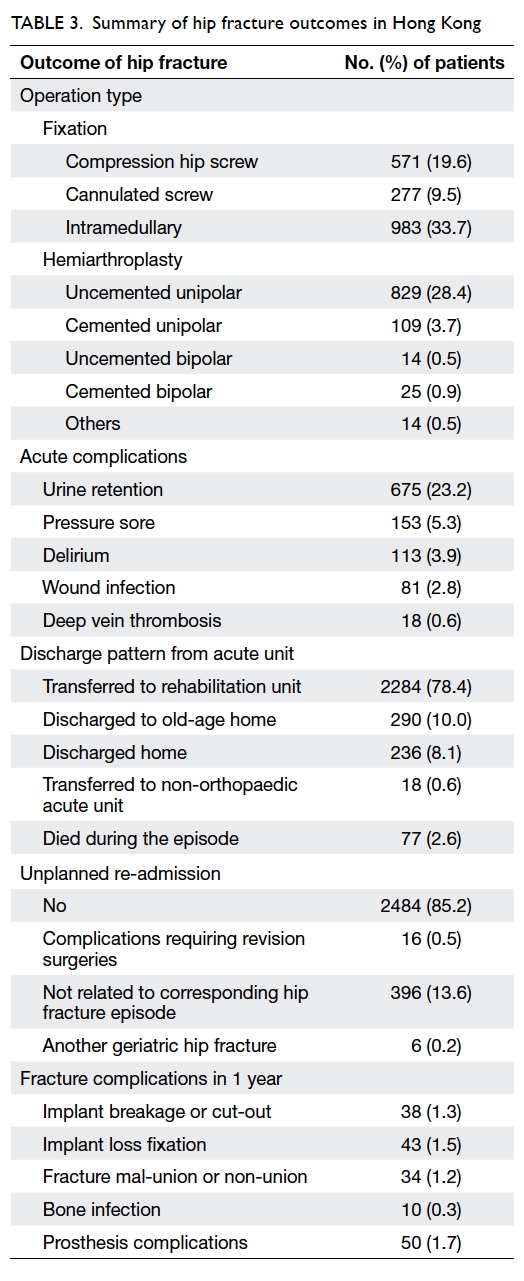

The safety endpoints and clinical outcomes are

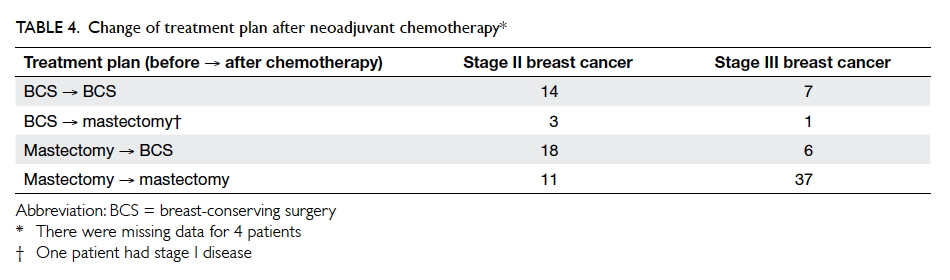

outlined in Table 3. Conversion to open heart

surgery after the procedure was necessary in two

patients, one of whom had a calcified valvular leaflet

that dislodged into the left atrium after device

implantation and required open exploration. The

other patient had incessant ventricular fibrillation,

possibly due to coronary obstruction during the

procedure, and required emergent cardiopulmonary

bypass and open heart surgery. Pre-procedural

CT revealed adequate coronary height (both left

coronary and right coronary ostium >16 mm above

annular plane) and adequate sinus of Valsalva

diameters. The coronary obstruction was thought to

be due to dislodged calcified nodules from the aortic

valve leaflets. This patient eventually died despite

SAVR under extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

support, and was the only hospital mortality

(1.8%).

Stroke occurred in one (1.8%) patient within

30 days. New conduction abnormalities requiring

permanent pacing were present in seven (12.5%)

patients. There were major access-related vascular

complications in five (8.9%) patients and three

(5.4%) had acute kidney injury stage 2 although none

required long-term dialysis and no patient had acute

kidney injury stage 3 (Table 3).

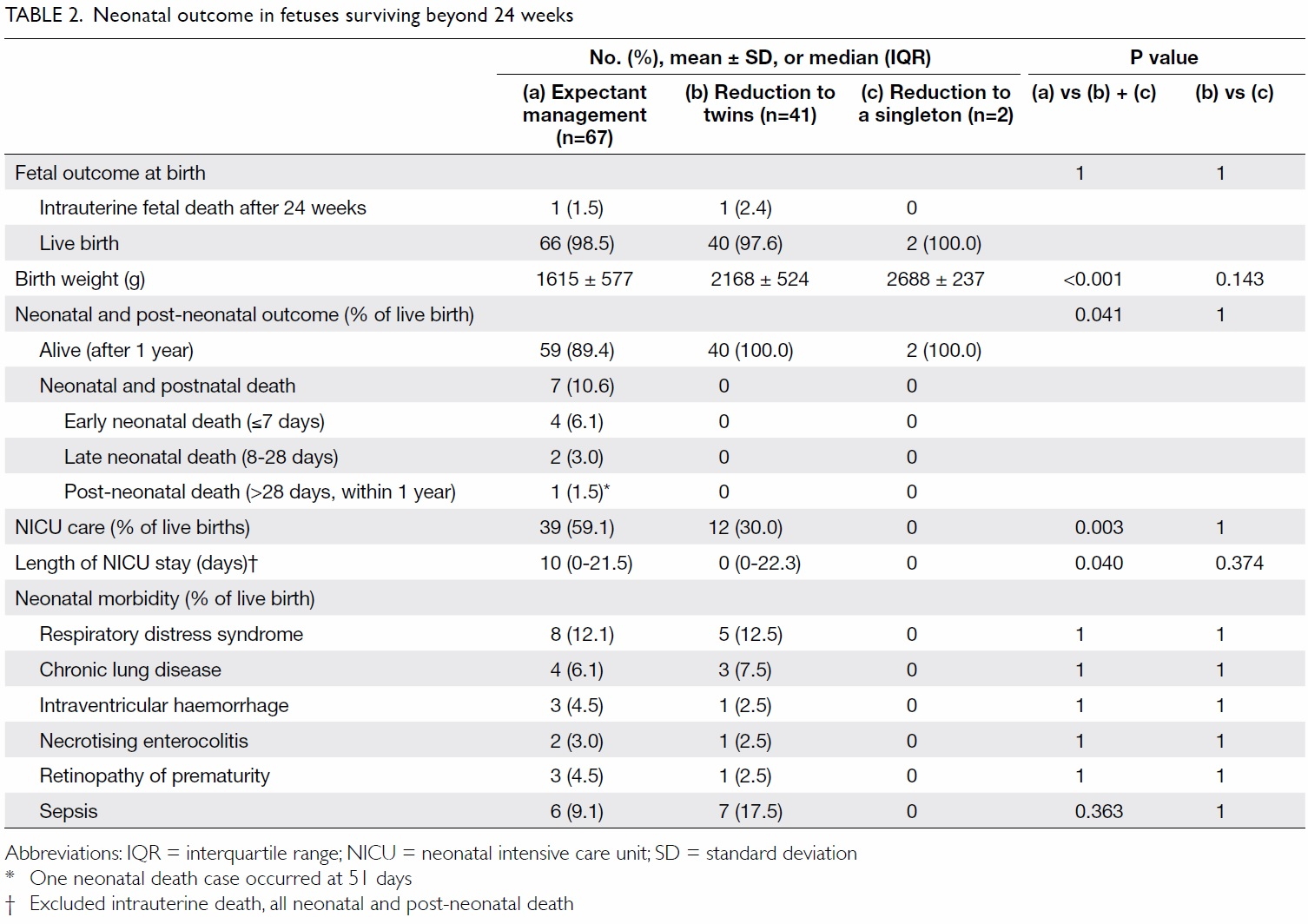

Follow-up results

Most patients (55/56, 98.2%) either had regular

follow-up or died. Only one patient who relocated

to Mainland China was lost to follow-up, although

his doctor keeps us updated regularly about his

condition. The longest follow-up period was 5

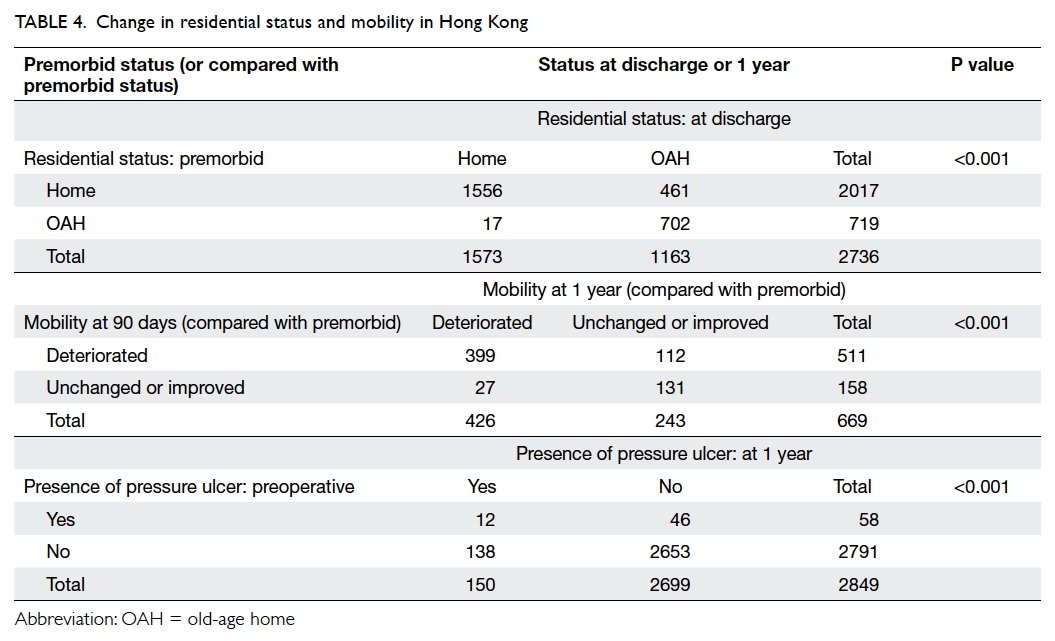

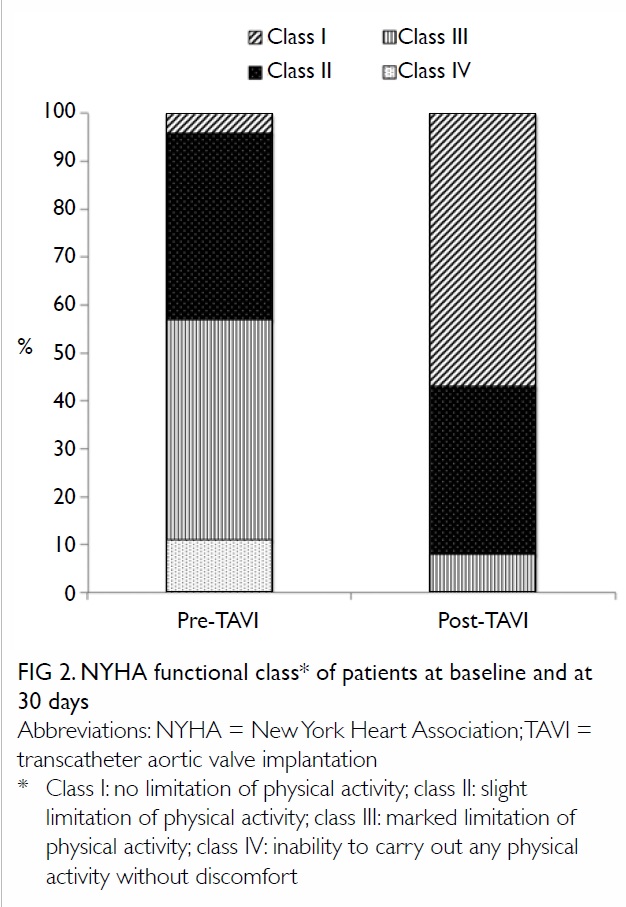

years. The 30-day mortality rate was 1.8%. The

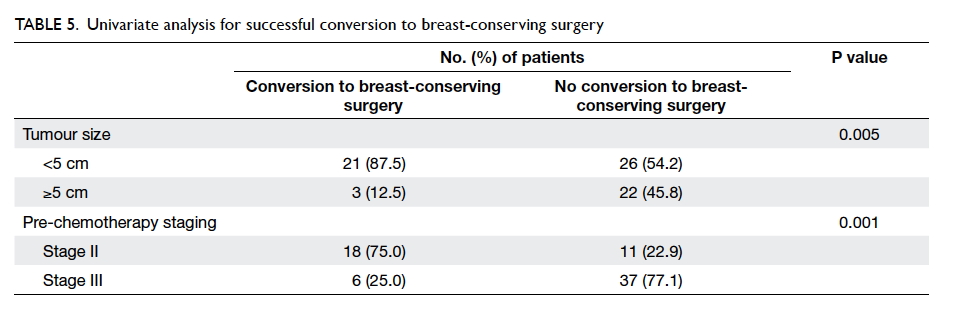

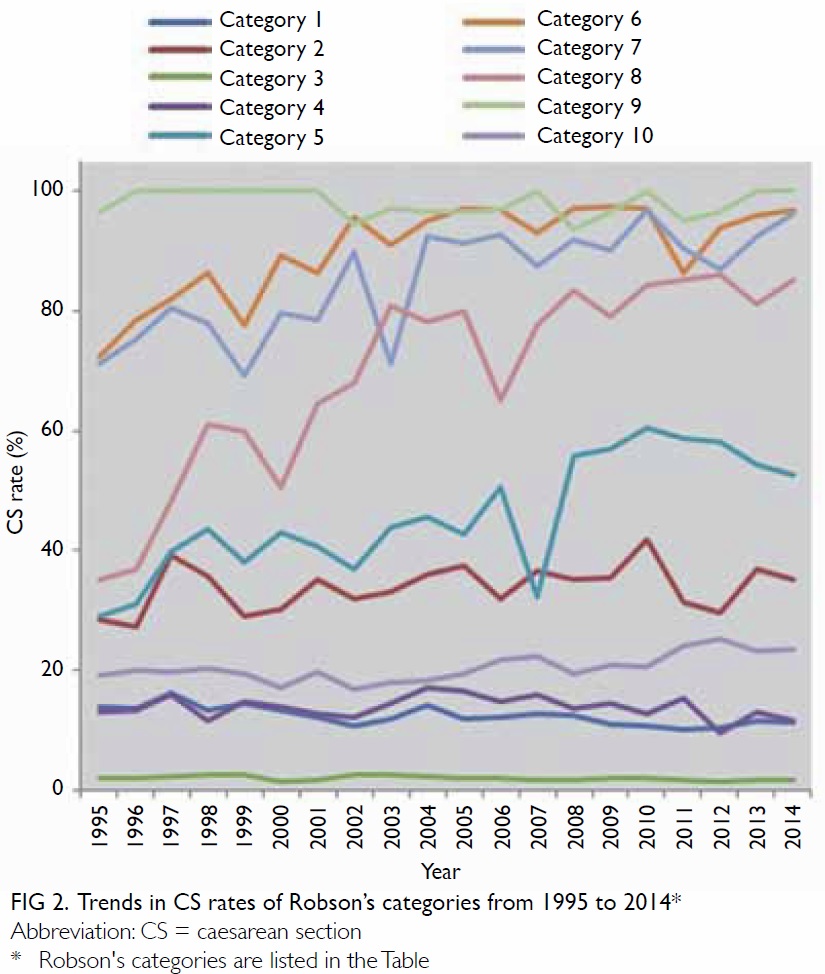

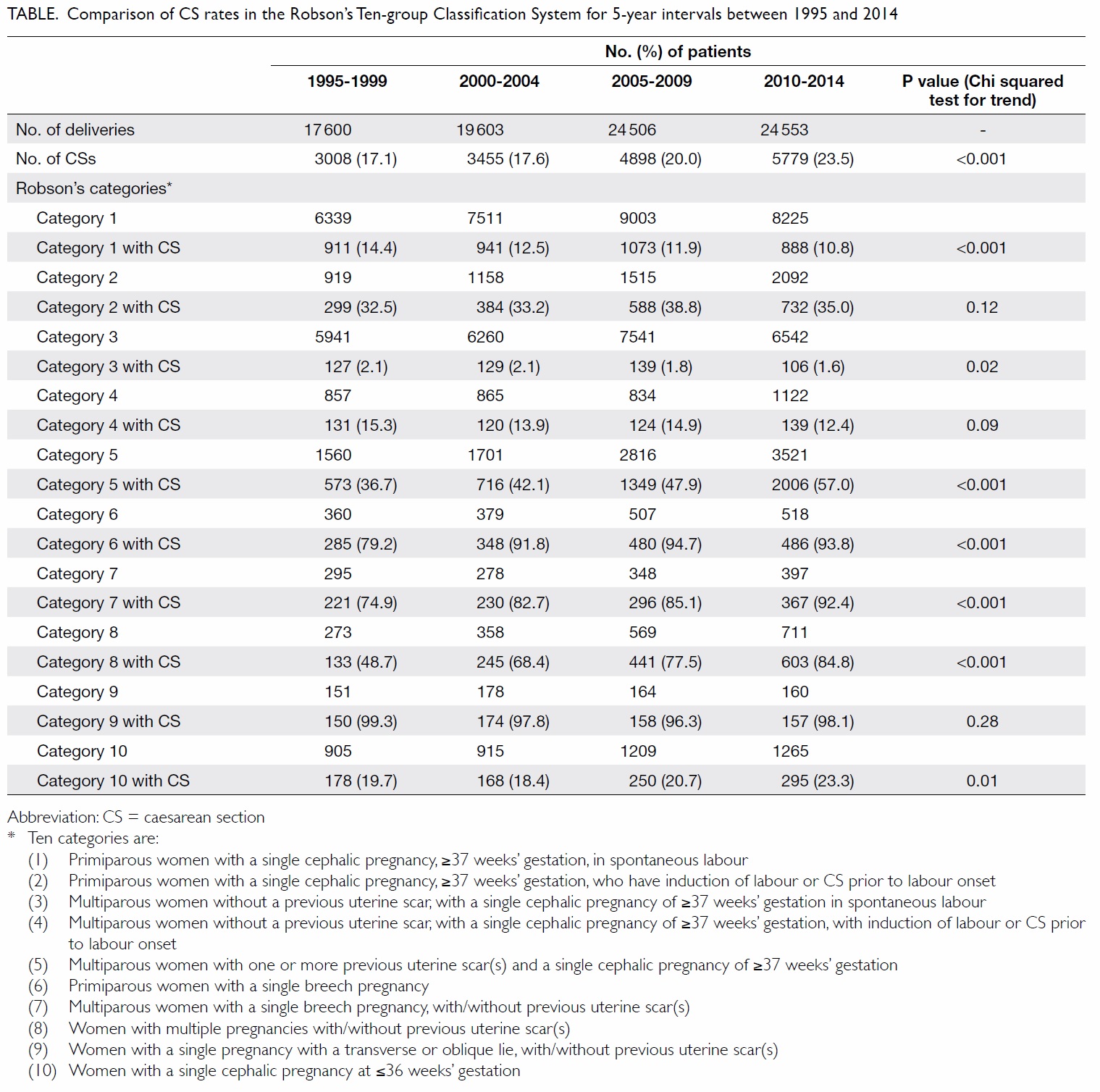

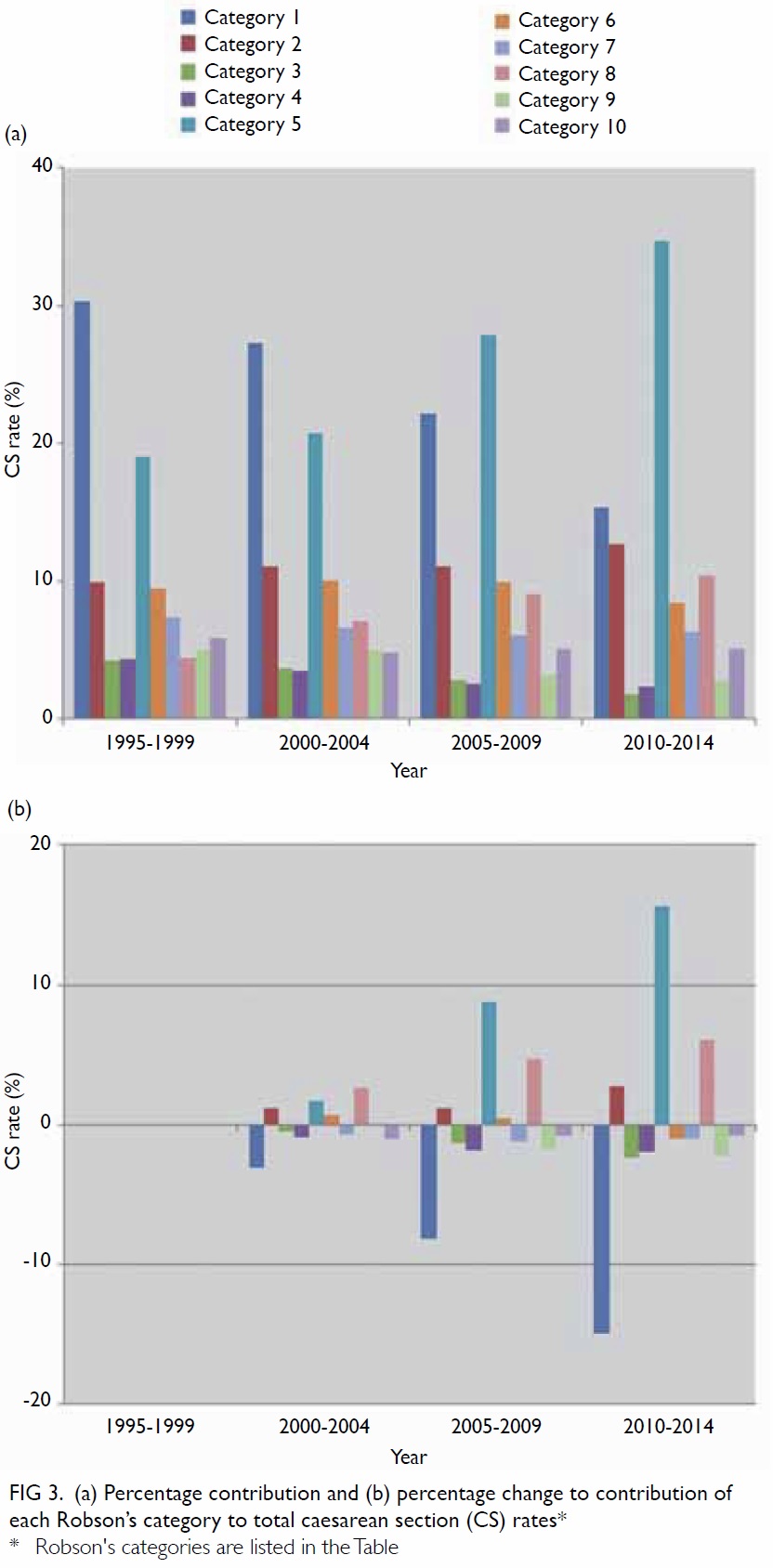

NYHA functional class of patients at baseline and

at 30 days is outlined in Figure 2; 92% of patients

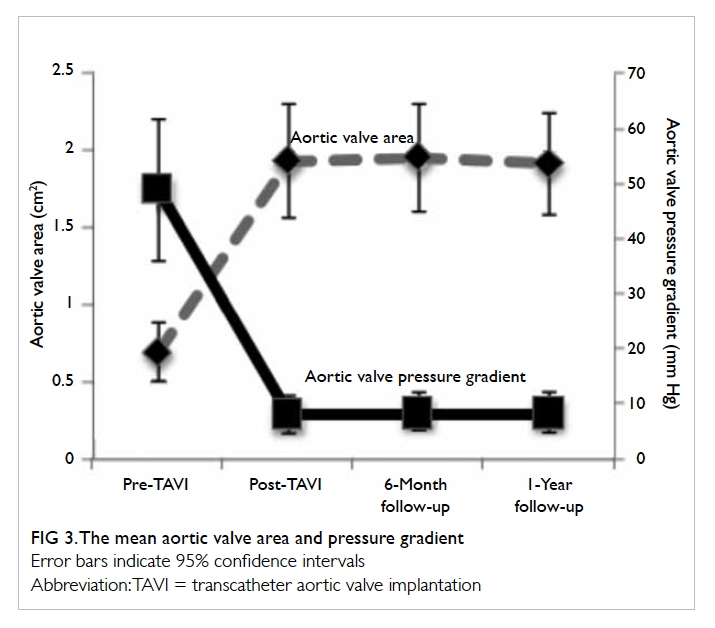

improved by at least one functional class. The mean

LVEF was 57.9% ± 10.9% at 30 days. The mean

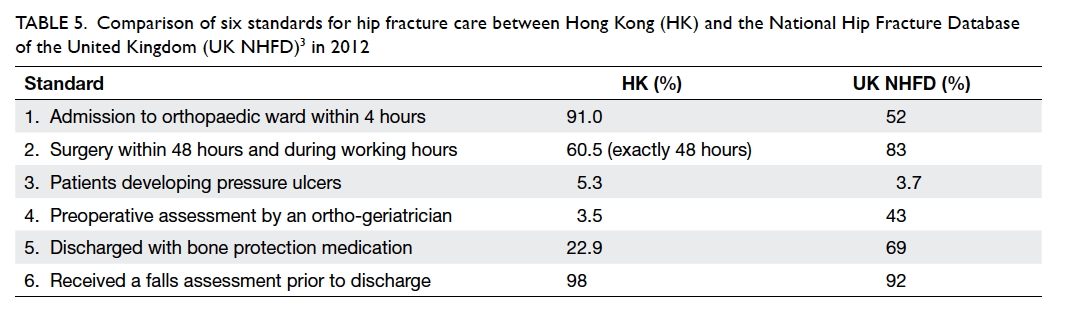

aortic valve area improved to 1.94 cm2 ± 0.37 cm2

and mean aortic transvalvular pressure gradient

improved to 8.1 mm Hg ± 3.4 mm Hg (Fig 3). These

improvements persisted at 6-month and 1-year

follow-up assessment. The 6-month all-cause and

cardiovascular mortalities were 8.9% and 5.4%,

respectively. The 1-year all-cause and cardiovascular

mortalities were 12.5% and 7.1%, respectively (Table 3). Causes of 1-year mortality included myocardial

infarction, heart failure with cardiogenic shock, liver failure, pneumonia, and sepsis with disseminated

intravascular coagulopathy.

Discussion

This is the first report to describe the clinical

experience of TAVI in a major tertiary referral

hospital, which is also the first hospital in Hong

Kong to introduce this technology and having the

largest case volume in Hong Kong up until the end

of 2015. The clinical outcomes of our cohort show

very promising results.

Since 2010, there have been several

landmark clinical trials describing the initial

clinical outcome of TAVI in both high-surgical-risk

and inoperable patients. The PARTNER 1 was

a multicentre prospective randomised controlled

trial to investigate the balloon-expandable Edwards

SAPIEN valve (Edwards Lifesciences). PARTNER

1B arm randomised inoperable patients to TAVI or

best medical treatment and showed a 20% absolute

reduction in mortality rate at 1 year with TAVI.9

The PARTNER 1A arm randomised patients with

high surgical risk to either TAVI or SAVR and TAVI

was shown to be non-inferior to SAVR in terms of

mortality rate at 1 year (24% vs 26.8%; P=0.44).11

The US CoreValve pivotal trial randomised patients

with high surgical risk to either TAVI using the self-expanding

CoreValve or SAVR and demonstrated a

significant reduction in mortality rate at 1 year in

the TAVI group compared with the SAVR group

(14.2% vs 19.1%; P=0.04).10 The relatively high 1-year

mortality rate in those clinical trials is mainly due

to their baseline multiple co-morbidities and the

advanced age (mean age, 80 years) of patients.

The 1-year mortality rate of 12.5% in our cohort

compares well with these landmark trials. The risk

profile of our patient group is nonetheless not lower

(logistic EuroSCORE of 22% in our group vs 18%

in CoreValve pivotal trial). This high baseline risk

factor accounts for the high 1-year mortality rate

although a significant proportion was related to

non-cardiac causes (3 out of 7). The current view is

to avoid treating the patients with too high risk and

who will not benefit from this high-risk procedure.

A reasonable 1-year expected survival is also a

prerequisite.12 13

Other complication rates of our cohort also

compared well with the landmark trials. Significant

aortic regurgitation secondary to paravalvular

leak (PVL) is a unique problem not uncommonly

encountered following TAVI in contrast to patients

who undergo SAVR in whom there is usually no

residual leakage.14 15 One study showed that even mild

PVL after TAVI is associated with higher mortality

rate at 2 years.16 Treatment of significant PVL is by

post-dilation, putting in another valve (so called

‘valve in valve’) or using a vascular plug. The rate of

moderate or severe PVL in both the PARTNER 1B9 and US CoreValve pivotal trial10 was approximately

7%. No moderate or severe PVL was noted in our study due to the

high rate of using two valves (‘valve in valve’) in 16%

of our cohort compared with the reported 4% rate

in the US CoreValve pivotal trial. With increasing

experience and availability of a repositionable

device, however, progressively fewer cases required

more than one valve.

Some of the complications after TAVI are

more disabling than others, such as stroke. The

major stroke rate in both the PARTNER and US

CoreValve pivotal trial was approximately 5%.9 10 Major stroke rate in one meta-analysis of more

than 10 000 patients was 3.3%.17 Clinical stroke

occurred in only one (1.8%) patient in our cohort.

This is probably because of our small sample size, as

well as the random and unpredictable nature of this

complication. More cases of stroke would be expected

if more patients were treated. The latest clinical

trial using next-generation TAVI devices resulted

in a much lower rate of stroke after TAVI (0.9% at

30 days and 2.4% at 1 year for high-risk patients).18

The aetiology of stroke after TAVI is multifactorial

and includes embolism of valvular material during

balloon valvuloplasty, device manipulation across an

atheromatous aorta, and atrial fibrillation.19 Multiple

strategies to reduce periprocedural stroke have

been attempted including direct stenting, avoidance

of pre- or post-dilation, use of cerebral protection

devices and different antithrombotic regimens.20 21

Currently, randomised trials are underway to

determine whether cerebral protection devices are

useful in reducing periprocedural stroke.22

Conduction abnormality is another common

event following TAVI. The reported rate of

permanent pacemaker implantation to treat high-grade

heart block varies from 10% to 30% and

it depends very much on type and implantation

depth of the device.23 24 25 26 The rate reported in the US

CoreValve pivotal trial was 20% at 1 month and 22%

at 1 year.10 The permanent pacemaker implantation

rate in our cohort was 12.5% with the majority of our

cases having a self-expandable valve. In our cohort,

most pacemakers were implanted earlier on in the

study period when we were more cautious about

treating post-procedural conduction abnormalities.

Major vascular complications occurred in

approximately 6% of patients in the US CoreValve

pivotal trial and 11% in PARTNER 1 trial.9 10 Rates

of major vascular complications in different

observational and randomised trials range from 5%

to 17%.27 The lower rate in the US CoreValve pivotal

trial can be explained by the smaller size of the

introducer sheath for CoreValve (18 Fr) compared

with the much bigger 22-24 Fr sheath for the first-generation

SAPIEN device in the PARTNER 1 trial.9 For the same reason and the relative smaller size of

peripheral vessels in an Asian population, we would

expect a higher rate of vascular complications.

Indeed, the major vascular complication rate in

our cohort was 8.9%, which is compatible with

the worldwide standard. This is the result of our

comprehensive use of CT angiogram for all cases

from the beginning of the cohort to delineate the

size of the peripheral vessels and better plan of

procedural strategies.

Overall, the success of the procedure depends

not only on the technical requirement in a very high-risk

group of patients but also a comprehensive,

multidisciplinary team approach. This ‘heart

team’ approach is the cornerstone of the rapidly

developing field of structural heart intervention

and preferred strategies in dealing with anticipated

complications.27

After the success in treating high-risk

patients with aortic stenosis, the recently published

PARTNER 2 trial evaluated TAVI and SAVR

in patients with intermediate surgical risk. It

randomised patients with intermediate surgical risk

to either TAVI or SAVR; TAVI was non-inferior to

SAVR in terms of all-cause mortality and disabling

stroke at 2 years (19.3% in TAVI group vs 21.1% in

SAVR group; P=0.25).28 Another major trial testing

TAVI in intermediate-risk patients, the SURTAVI

Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01586910),

has completed patient recruitment and the results

will be available very soon.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study include the

relatively small sample size and a single-centre early

experience. The technology is evolving and lower- or

intermediate-risk patients are being treated in

various clinical trials. With an increasing awareness

of the disease and referrals from around the territory,

the population being treated is expected to increase

in the coming years.

Conclusions

The technique TAVI has been developed as an

alternative treatment for patients with symptomatic

severe aortic stenosis who are deemed inoperable

or high risk for surgery. It has been proven in major

randomised controlled trials to have an acceptable

complication rate and durability in the medium

term. Our results are very promising and comparable

with those of major clinical trials. Long-term clinical

outcomes should be diligently monitored.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Women and men in Hong Kong—key statistics. 2015

Edition. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11303032015AN15B0100.pdf. Accessed 26 Jun 2016.

2. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott

CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases:

a population-based study. Lancet 2006;368:1005-11. Crossref

3. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of

Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on

Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:e57-185. Crossref

4. Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, et al. Guidelines on

the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012):

the joint task force on the management of valvular heart

disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and

the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery

(EACTS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;42:S1-44. Crossref

5. Turina J, Hess O, Sepulcri F, Krayenbuehl HP. Spontaneous

course of aortic valve disease. Eur Heart J 1987;8:471-83. Crossref

6. Kvidal P, Bergström R, Hörte LG, Ståhle E. Observed and relative survival after aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll

Cardiol 2000;35:747-56. Crossref

7. Kvidal P, Bergström R, Malm T, Ståhle E. Long-term

follow-up of morbidity and mortality after aortic valve

replacement with a mechanical valve prosthesis. Eur Heart

J 2000;21:1099-111. Crossref

8. Bouma BJ, van Den Brink RB, van der Meulen JH, et al. To

operate or not on elderly patients with aortic stenosis: the

decision and its consequences. Heart 1999;82:143-8. Crossref

9. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve

implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who

cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1597-607. Crossref

10. Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, et al. Transcatheter

aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis.

N Engl J Med 2014;370:1790-8. Crossref

11. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus

surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N

Engl J Med 2011;364:2187-98. Crossref

12. Miller DC. TAVI has a limited role in the treatment of AS.

American Association of Thoracic Surgery 2012 Annual

Meeting; 2012 Apr 29; San Francisco, United States.

13. Gilard M, Eltchaninoff H, Lung B, et al. Registry of

transcatheter aortic-valve implantation in high-risk

patients. N Engl J Med 2012;366;1705-15. Crossref

14. Lerakis S, Hayek SS, Douglas PS. Paravalvular aortic leak

after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: current

knowledge. Circulation 2013;127:397-407. Crossref

15. Généreux P, Head SJ, Hahn R, et al. Paravalvular leak after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the new Achilles’ heel? A comprehensive review of the literature. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1125-36. Crossref

16. Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al. Two-year

outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1686-95. Crossref

17. Eggebrecht H, Schmermund A, Voigtländer T, Kahlert

P, Erbel R, Mehta RH. Risk of stroke after transcatheter

aortic valve implantation (TAVI): a meta-analysis of 10,037

published patients. EuroIntervention 2012;8:129-38. Crossref

18. Herrmann HC. SAPIEN 3: Evaluation of a balloon-expandable

transcatheter aortic valve in high-risk and

inoperable patients with aortic stenosis with aortic TCT.

San Francisco 2015 Oct 15.

19. Mastoris I, Schoos MM, Dangas GD, Mehran R. Stroke

after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: incidence,

risk factors, prognosis, and preventive strategies. Clin

Cardiol 2014;37:756-64. Crossref

20. Ghanem A, Naderi AS, Frerker C, Nickenig G, Kuck

KH. Mechanisms and prevention of TAVI-related

cerebrovascular events. Curr Pharm Des 2016;22:1879-87. Crossref

21. Schmidt T, Schlüter M, Alessandrini H, et al. Histology

of debris captured by a cerebral protection system

during transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation. Heart

2016;102:1573-80. Crossref

22. Kodali S. Cerebral embolic protection devices: Sentinel

dual filter device. Update of US Pivotal Clinical Trial. TCT

2015; 2015 Oct 11-15; San Francisco, United States.

23. Webb JG, Altwegg L, Boone RH, et al. Transcatheter aortic

valve implantation: impact on clinical and valve-related

outcomes. Circulation 2009;119:3009-16. Crossref

24. Piazza N, Grube E, Gerckens U, et al. Procedural and

30-day outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve

implantation using the third generation (18 Fr) corevalve

revalving system: results from the multicentre, expanded

evaluation registry 1-year following CE mark approval.

EuroIntervention 2008;4:242-9. Crossref

25. Jilaihawi H, Chin D, Vasa-Nicotera M, et al. Predictors for

permanent pacemaker requirement after transcatheter

aortic valve implantation with the CoreValve bioprosthesis.

Am Heart J 2009;157:860-6. Crossref

26. Kanmanthareddy A, Buddam A, Sharma S, et al. Complete

heart block after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a

meta-analysis. Circulation 2014;130:A15832.

27. Toggweiler S, Leipsic J, Binder RK, et al. Management of

vascular access in transcatheter aortic valve replacement:

part 2: Vascular complications. JACC Cardiovasc Interv

2013;6:767-76. Crossref

28. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter or

surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk

patients. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1609-20. Crossref

A video clip showing triplet pregnancy with fetal reduction skills

A video clip showing triplet pregnancy with fetal reduction skills