Pathological outcome for Chinese patients with low-risk prostate cancer eligible for active surveillance and undergoing radical prostatectomy: comparison of six different active surveillance protocols

Hong

Kong Med J 2017 Dec;23(6):609–15 | Epub 13 Oct 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166194

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Pathological outcome for Chinese patients with low-risk

prostate cancer eligible for active surveillance and undergoing radical

prostatectomy: comparison of six different active surveillance protocols

CF Tsang, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin); James HL Tsu, MB,

BS, FRCS (Edin); Terence CT Lai, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin); KW Wong, MB, ChB,

FRCS (Edin); Brian SH Ho, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin); Ada TL Ng, MB, BS, FRCS

(Edin); WK Ma, MB, ChB, FRCS (Edin); MK Yiu, MB, BS, FRCS (Edin)

Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Queen

Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr MK Yiu (pmkyiu@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Active

surveillance is one of the therapeutic options for the management of

patients with low-risk prostate cancer. This study compared the

performance of six different active surveillance protocols for prostate

cancer in the Chinese population.

Methods: Patients who underwent

radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer from January 1998 to December

2012 at a university teaching hospital in Hong Kong were reviewed. Six

active surveillance protocols were applied to the cohort. Statistical

analyses were performed to compare the probabilities of missing

unfavourable pathological outcome. The sensitivity and specificity of

each protocol in identifying low-risk disease were compared.

Results: During the study

period, 287 patients were included in the cohort. Depending on different

active surveillance protocols used, extracapsular extension, seminal

vesicle invasion, pathological T3 disease, and upgrading of Gleason

score were present on final pathology in 3.3%-17.1%, 0%-3.3%,

3.3%-19.1%, and 20.6%-34.5% of the patients, respectively. The

University of Toronto protocol had a higher rate of extracapsular

extension at 17.1% and pathological T3 disease at 19.1% on final

pathology than the more stringent protocols from John Hopkins (3.3%

extracapsular extension, P=0.05 and 3.3% pathological T3 disease,

P=0.03) and Prostate Cancer Research International: Active Surveillance

(PRIAS; 8.0% pathological T3 disease, P=0.04). The Royal Marsden

protocol had a higher rate of upgrading of Gleason score at 34.5%

compared with the more stringent protocol of PRIAS at 20.6% (P=0.04).

The specificities in identifying localised disease and low-risk

histology among different active surveillance protocols were 59%-98% and

58%-94%, respectively. The John Hopkins active surveillance protocol had

the highest specificity in both selecting localised disease (98%) and

low-risk histology (94%).

Conclusions: Active surveillance

protocols based on prostate-specific antigen and Gleason score alone or

including Gleason score of 3+4 may miss high-risk disease and should be

used cautiously. The John Hopkins and PRIAS protocols are highly

specific in identifying localised disease and low-risk histology.

New knowledge added by this study

- Active surveillance protocols based on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and Gleason score only may miss high-risk prostate cancer.

- Active surveillance protocols using PSA density as an inclusion criteria were highly specific in identifying localised disease and low-risk pathology.

- When adopting active surveillance in patients with prostate cancer, protocols with PSA density as an inclusion criteria are preferred.

Introduction

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) plays a significant

role in the early detection of prostate cancer in current practice.1 2 It is,

however, a double-edged sword that leads to overdiagnosis, especially for

clinically insignificant prostate cancer.3

4 Curative treatments for low-risk

prostate cancer include radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy, both of

which are associated with significant morbidities.5 6 7 In recent years, the concept of active surveillance

(AS) has been adopted with the aim of monitoring clinically insignificant

prostate cancer until disease progression, at which point radical

prostatectomy or radiotherapy is considered. The ultimate objective is to

delay or avoid the morbidities associated with radical treatments without

compromising survival.8 9 10

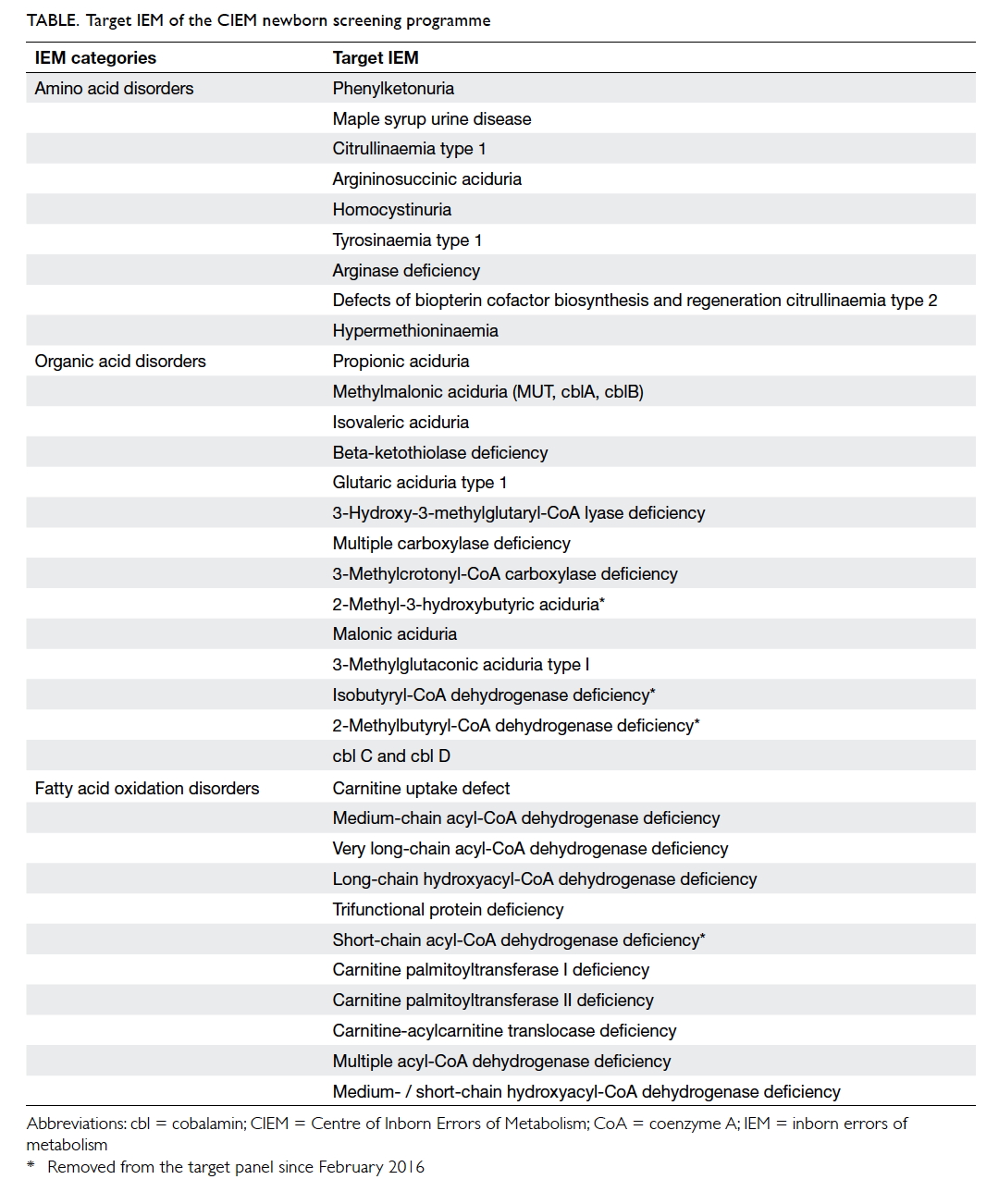

Although AS is an established management option for

low-risk prostate cancer, different AS protocols have been adopted.11 12 13 14 15 16 17 The most commonly used include those from the

University of Toronto,11 Royal

Marsden,12 John Hopkins,13 14

University of California San Francisco (UCSF),15

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC),16

and Prostate Cancer Research International: Active Surveillance (PRIAS).17 Most AS protocols select

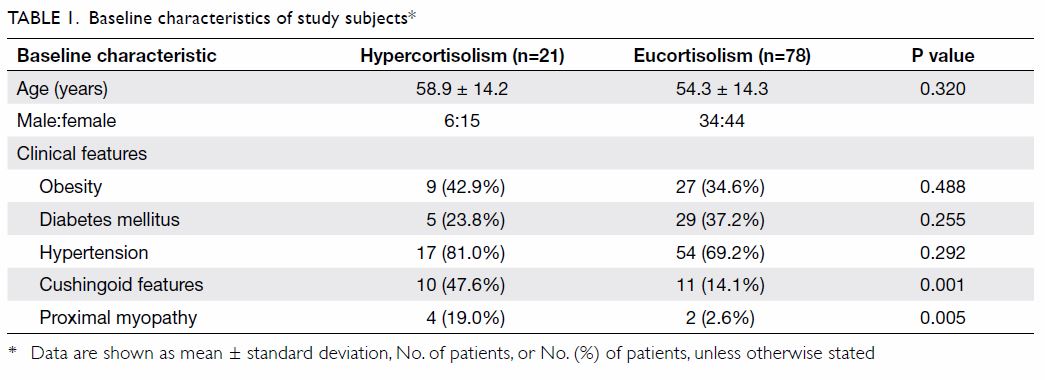

prostate cancer with a Gleason score of ≤6, PSA level of ≤10 ng/mL, and

clinical stage of ≤T2. Other parameters that are considered by some

protocols include PSA density, number of positive biopsy cores, and

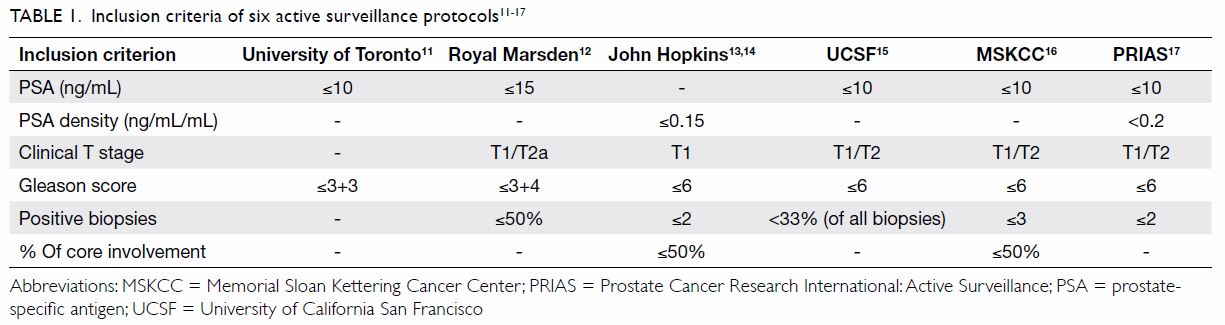

percentage of core involvement (Table 111 12 13

14 15

16 17).

Currently, there is no consensus regarding which AS

protocol we should adopt for our patients. In addition, direct comparisons

between different AS protocols are few. Before deciding to follow any

particular AS protocol, urologists and oncologists should be aware of

their individual strengths and limitations. Our study aimed to provide

some insight into this issue by performing a head-to-head comparison of

six AS protocols.

Methods

Patients who underwent radical prostatectomy for

prostate cancer from January 1998 to December 2012 at a university

teaching hospital in Hong Kong were reviewed. Indication for radical

prostatectomy was localised prostate cancer in patients with a life

expectancy exceeding 10 years. All patients underwent clinical assessment

including clinical T staging by digital rectal examination, serum PSA

level, and transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Sextant biopsies

were performed from 1998 to 2002, but changed to 10-core biopsies from

2002 to 2011 and subsequently 12-core biopsies thereafter. Preoperative

magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate was routinely performed from

2007. From 1998 to 2007, open or laparoscopic radical prostatectomies were

performed. After November 2007, all prostatectomies at our institution

were performed with the da Vinci robotic surgery system. Pathological

assessment of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy and radical

prostatectomy specimens was performed by a specialist pathologist in our

institution. All patients attended a follow-up visit with physical

examination 2 weeks after operation, and physical examination with serum

PSA level checked every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for

the second year, and then annually thereafter. Data on patient

demographics, clinical T stage, serum PSA level, transrectal

ultrasound-guided biopsy results, and final pathology of radical

prostatectomy specimen were retrospectively retrieved by an independent

third party. Pathological assessment of the radical prostatectomy specimen

was performed by independent specialist pathologists.

In our current study, we compared six different AS

protocols, specifically from the University of Toronto,11 Royal Marsden,12

John Hopkins,13 14 UCSF,15

MSKCC,16 and PRIAS17 (Table 1). The six protocols were retrospectively

applied to our cohort and patients were stratified accordingly based on

clinical T stage, serum PSA level, PSA density, Gleason score on biopsy,

number of positive biopsy cores, and percentage of positive core

involvement. Data from the pathological assessment of radical

prostatectomy specimens including extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle

invasion, upgrading to pathological T3 disease, and upgrading of Gleason

score were analysed. The clinical data used in the AS protocols were those

available on diagnosis of prostate cancer and operations were performed

within 12 weeks of diagnosis.

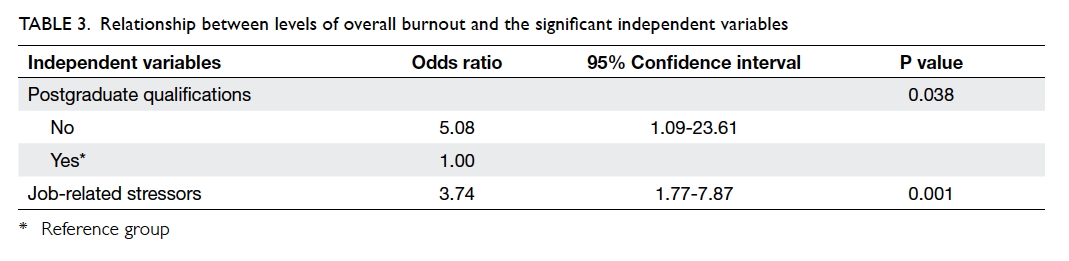

Statistical analyses to compare the rate of not

diagnosing clinically significant prostate cancer—defined as extracapsular

extension, seminal vesicle invasion, upgrading to T3 disease, and

upgrading of Gleason score in the final prostatectomy specimens—were

performed. The sensitivity and specificity of each protocol in selecting

localised prostate cancer (defined as pathological stage <T3) and

histological low-risk disease (defined as no upgrading of Gleason score on

final pathology) were compared.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS

(Windows version 20.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). Independent sample t test

and Pearson Chi-squared test were used for continuous and categorical

variables, respectively. A P value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant. This study was done in accordance with the

principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

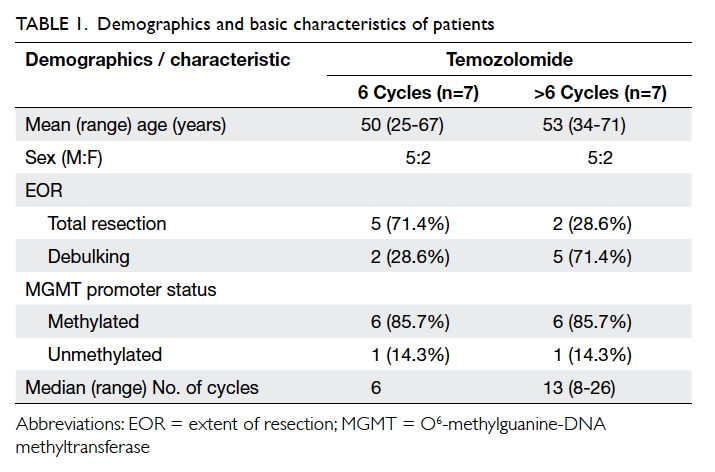

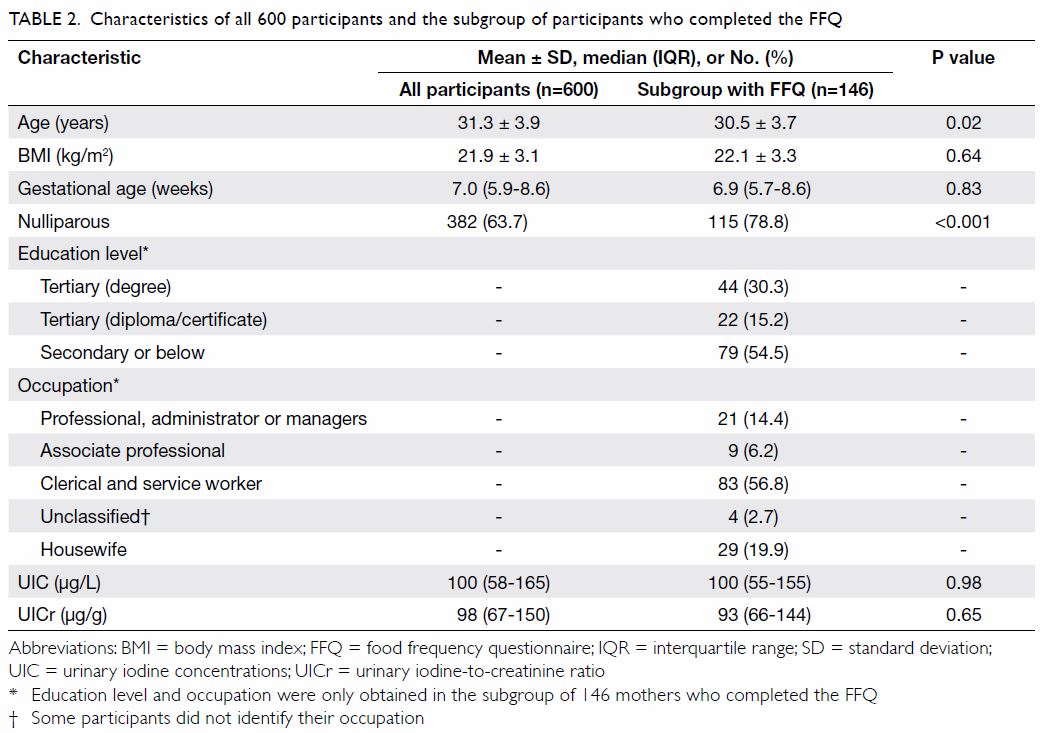

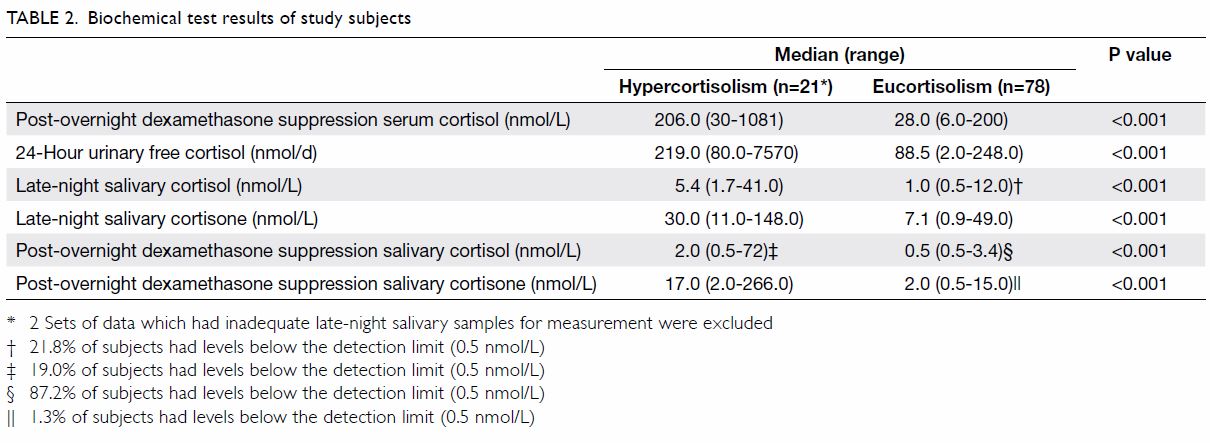

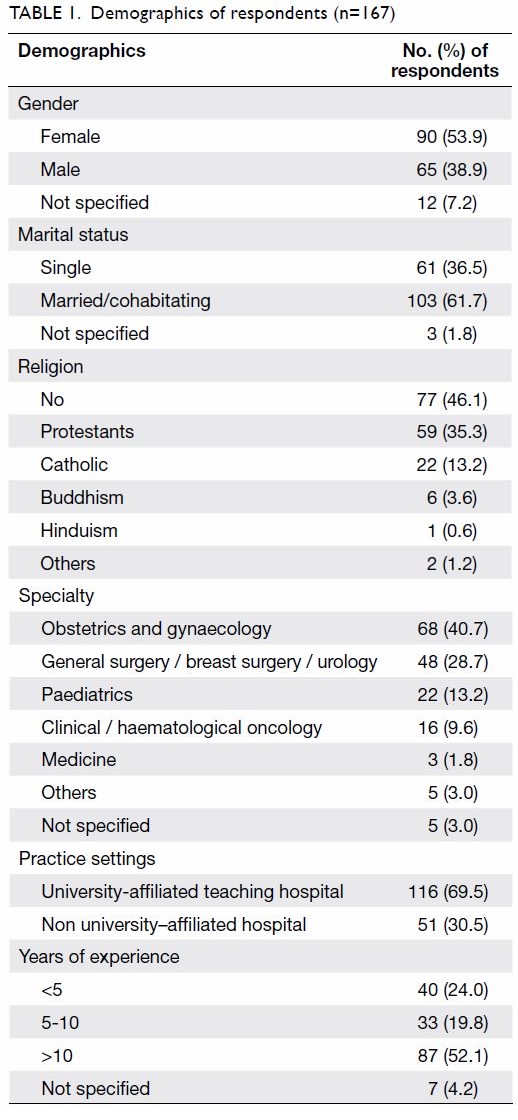

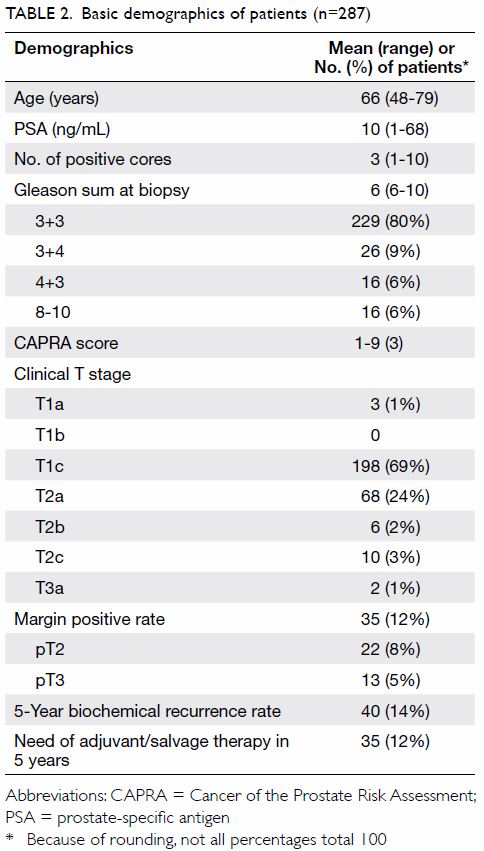

A total of 287 patients were included in the

cohort. The mean age was 66 years, mean serum PSA level was 10 ng/mL, mean

number of positive cores during biopsy was 3, and mean Gleason sum at

biopsy was 6. In the current cohort, 266 (93%) patients had clinical T1c

or T2a prostate cancer—198 (69%) had clinical T1c disease and 68 (24%) had

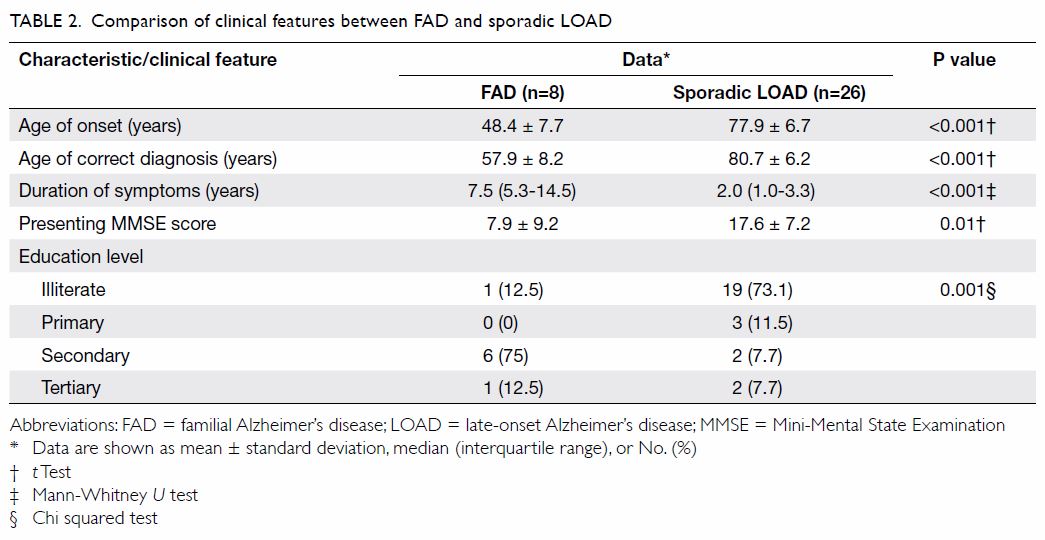

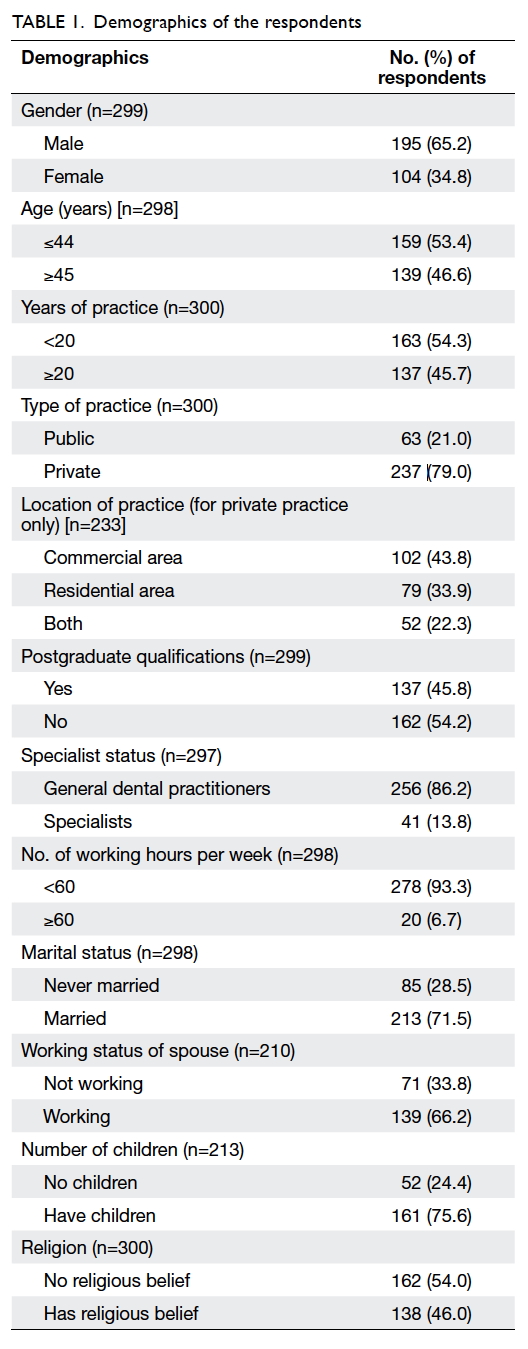

clinical T2a disease. Table 2 summarises the basic demographics of all

patients.

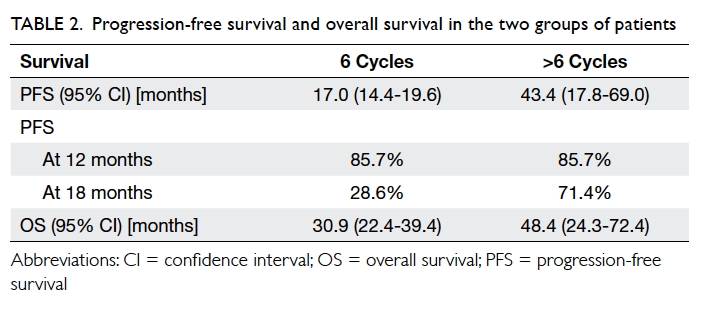

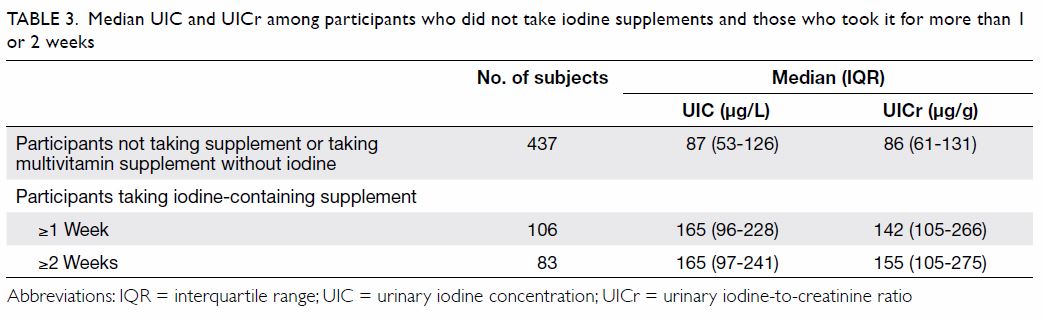

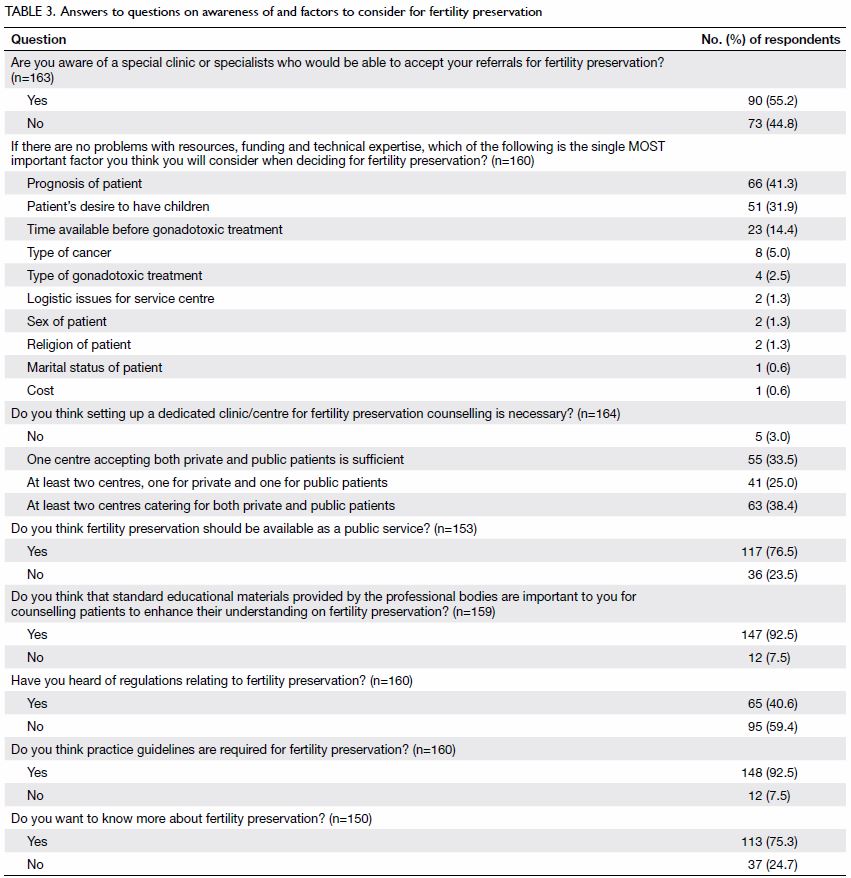

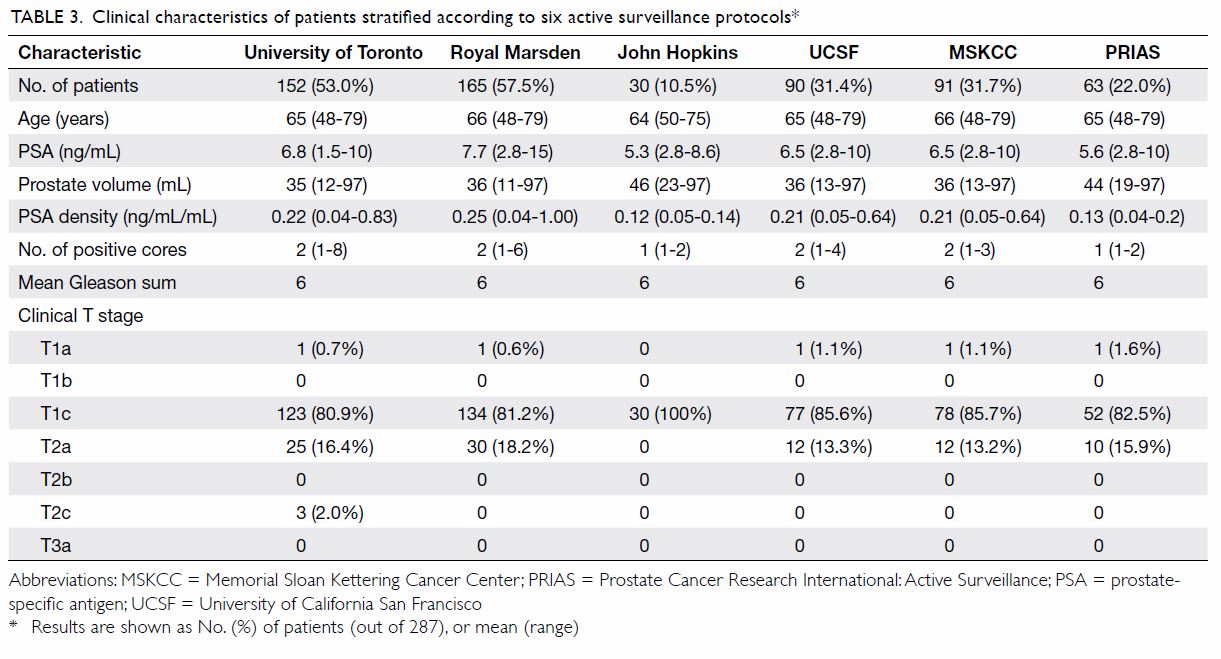

When the six AS protocols were applied to the

cohort, 30 to 152 patients were identified as low-risk; their mean serum

PSA level ranged from 5.3 ng/mL to 7.7 ng/mL, and mean PSA density ranged

from 0.12 ng/mL/mL to 0.25 ng/mL/mL. All six protocols had a mean biopsy

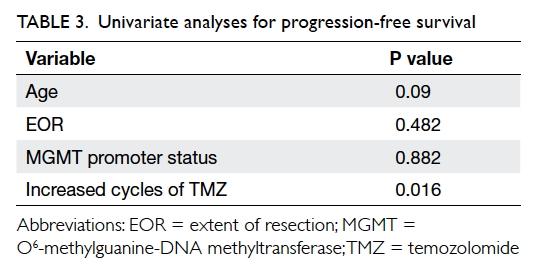

Gleason sum of 6. Table 3 summarises the clinical characteristics of

patients stratified according to different AS protocols.

Table 3. Clinical characteristics of patients stratified according to six active surveillance protocols

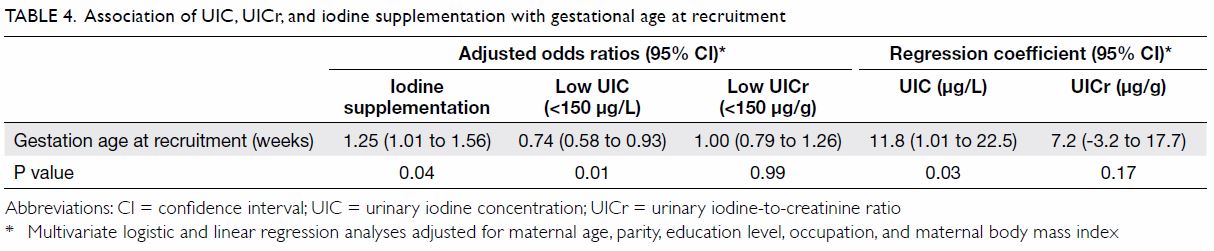

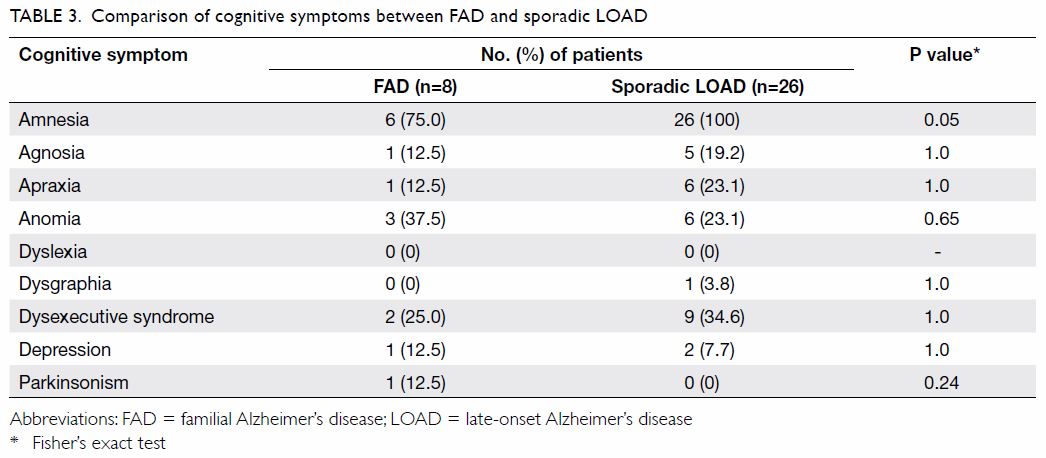

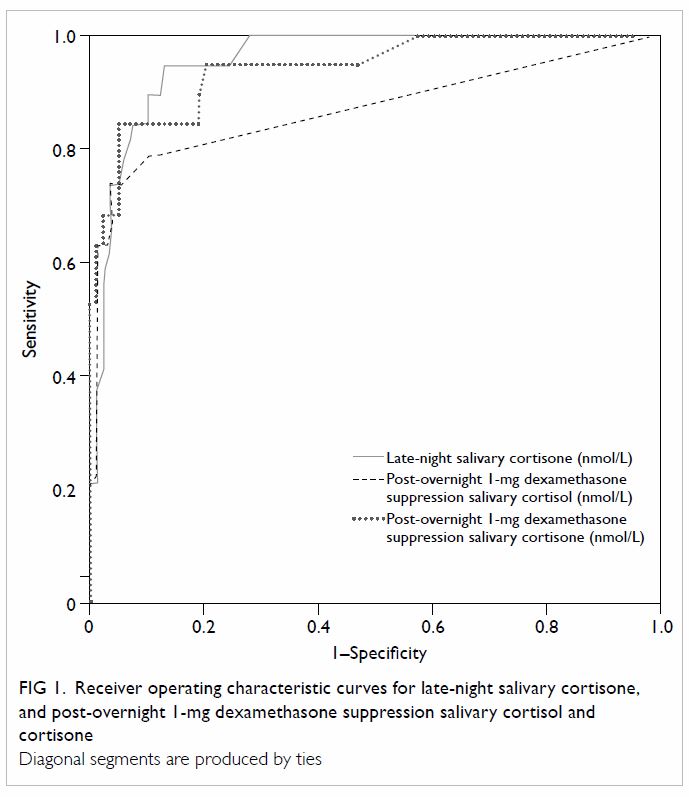

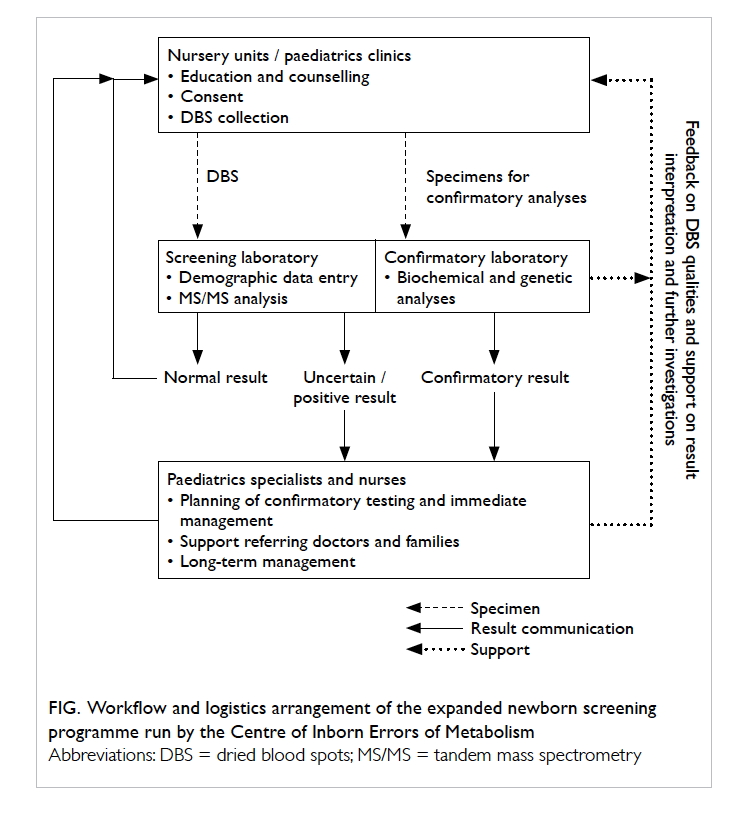

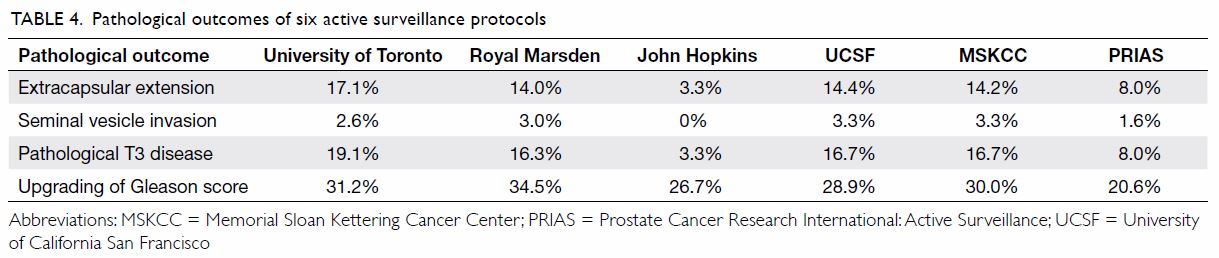

In the analyses of final pathological outcomes in

patients stratified into different AS protocols, extracapsular extension

rate varied from 3.3% to 17.1%. The incidence of seminal vesicle invasion

was low in all six protocols, ranging from 0% to 3.3%. The rate of

pathological T3 disease was lowest according to the John Hopkins criteria

(3.3%), while the University of Toronto criteria had the highest incidence

(19.1%). Regarding the upgrading of Gleason score in the radical

prostatectomy specimens, all six protocols had a relatively high rate

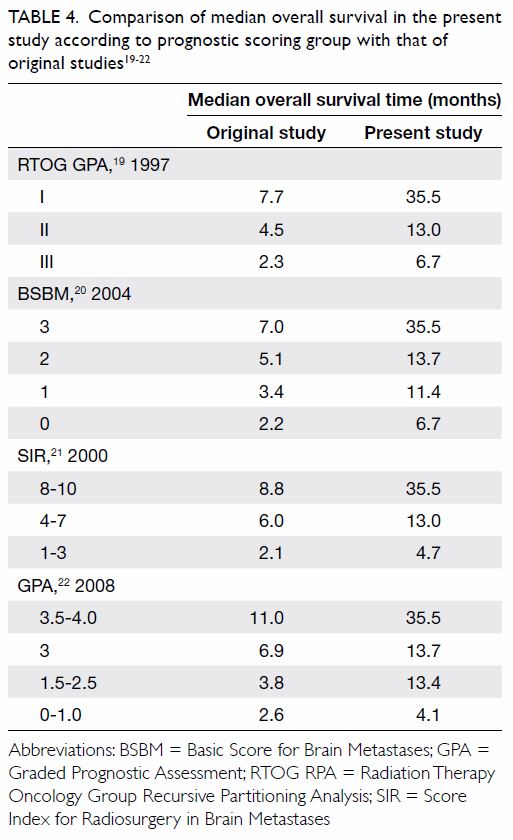

ranging from 20.6% to 34.5%. Table 4 summarises the pathological outcomes among

the six AS protocols.

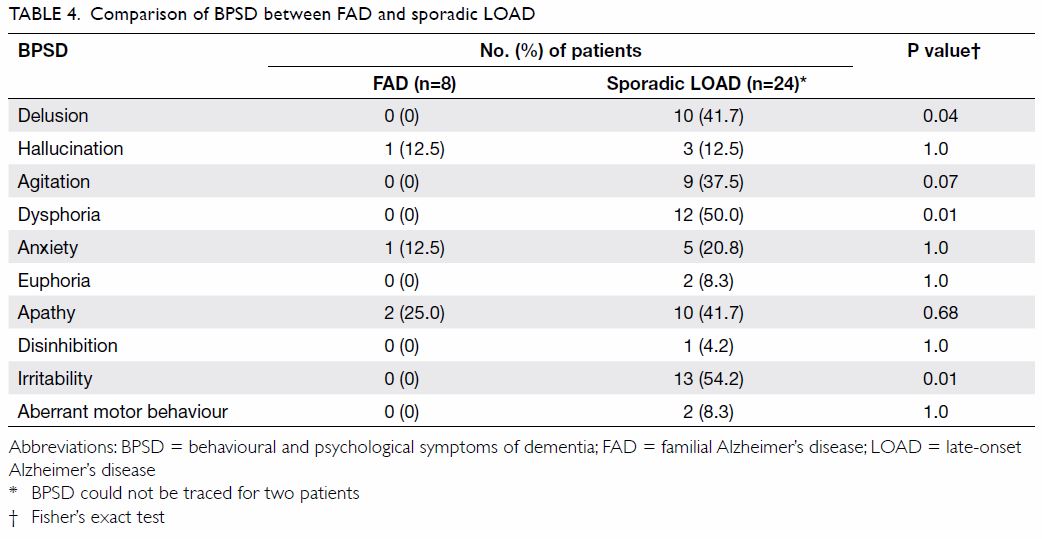

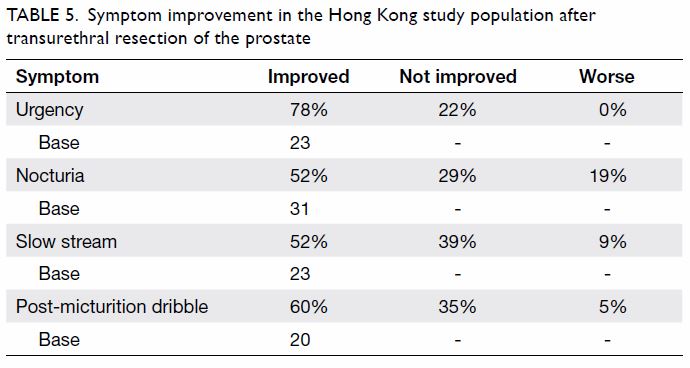

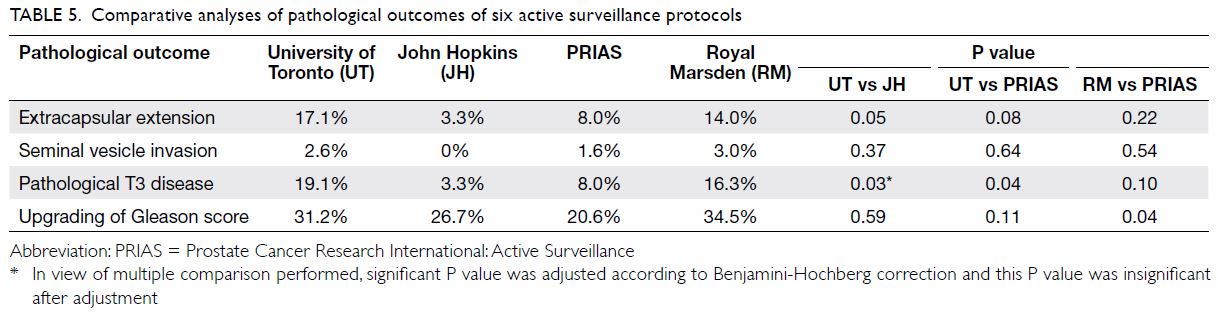

Comparative analyses of individual AS protocols

against each other were also performed (Table 5). The University of Toronto protocol had a

significantly higher rate of extracapsular extension at 17.1% and

pathological T3 disease at 19.1% when compared with the more stringent

protocol from John Hopkins (3.3% extracapsular extension, P=0.05 and 3.3%

pathological T3 disease, P=0.03) and PRIAS (8.0% pathological T3 disease,

P=0.04). In addition, the Royal Marsden protocol had a significantly

higher rate of upgrading of Gleason score at 34.5% when compared with the

more stringent protocol of PRIAS at 20.6% (P=0.04). There was no

significant difference in the incidence of seminal vesicle invasion

between the six protocols.

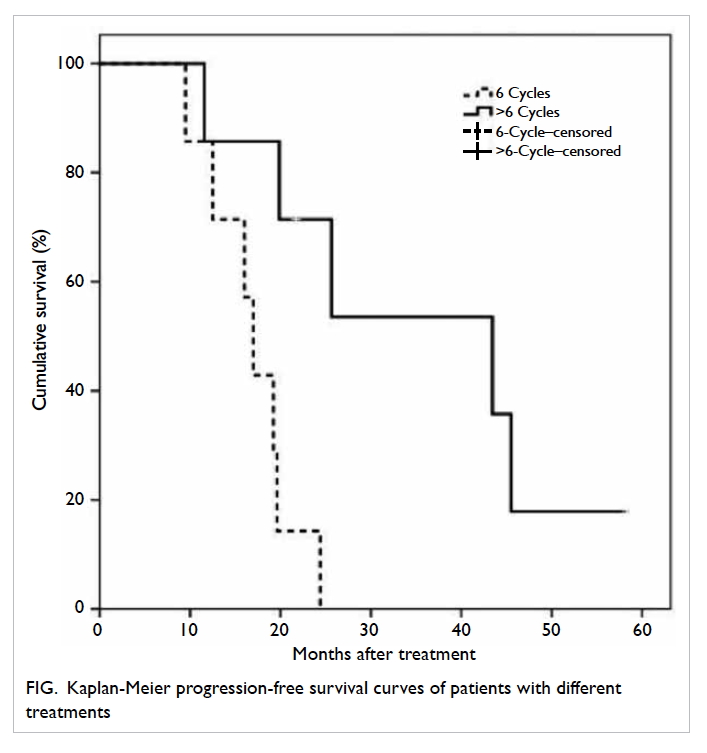

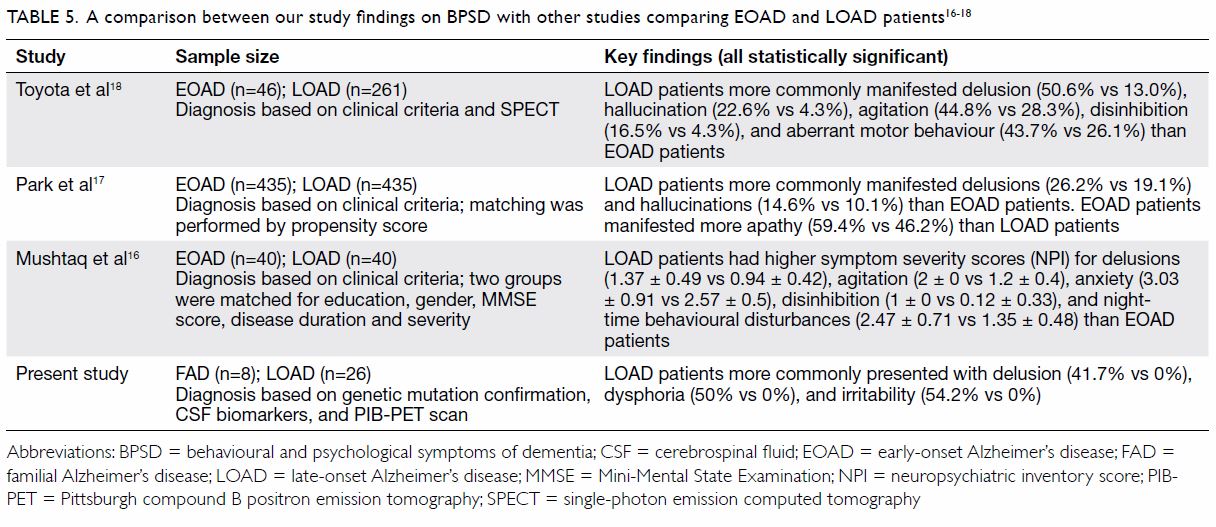

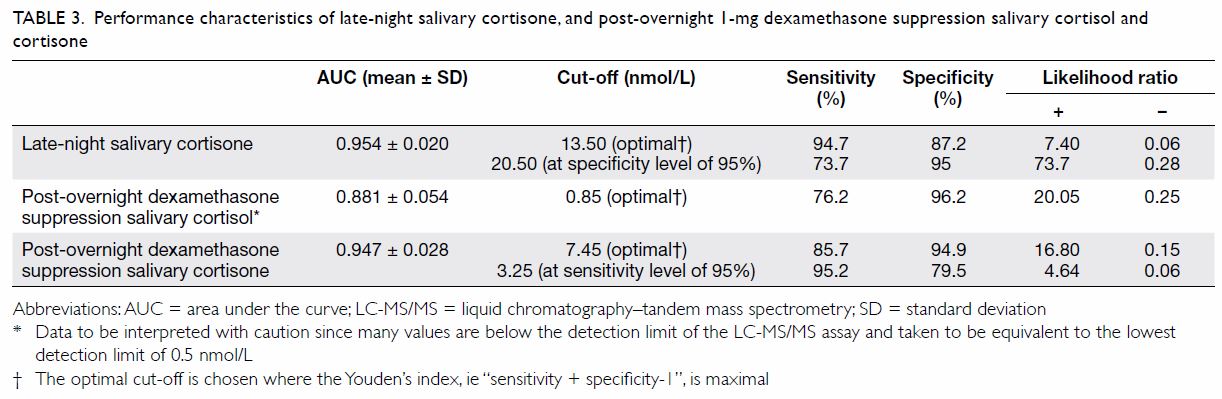

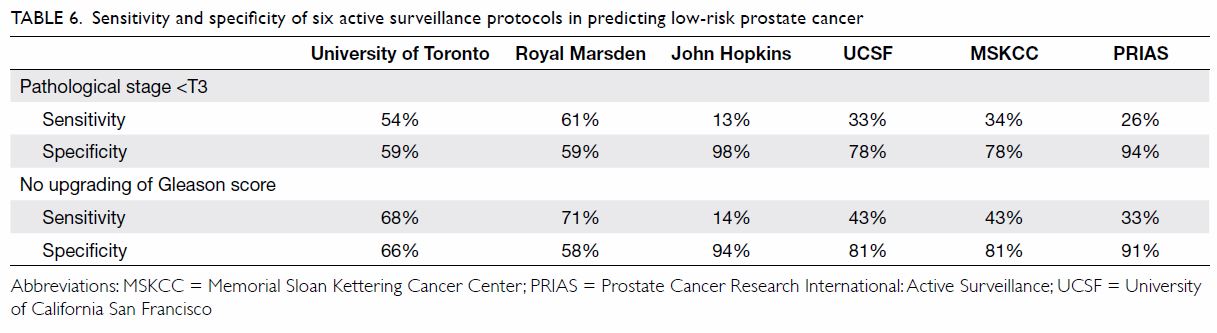

In terms of the ability of each protocol to

identify pathological localised disease (defined as pathological stage

<T3) and histologically low-risk cancer (defined as no upgrading of

Gleason score), sensitivity varied from 13%-61% and 14-71%, respectively.

The John Hopkins criteria demonstrated highest specificity in identifying

pathological localised disease (98%) and histological low-risk cancer

(94%). Table 6 illustrates the sensitivity and specificity

of identifying localised and histological low-risk disease for the six AS

protocols.

Table 6. Sensitivity and specificity of six active surveillance protocols in predicting low-risk prostate cancer

Discussion

Prostate cancer screening has always been a

controversial issue and evidence of improved survival is awaited.1 2 Nonetheless,

PSA screening has undoubtedly led to overdiagnosis of insignificant

prostate cancer.3 4 Active surveillance, with the purpose to delay or even

avoid radical treatments and their associated morbidities, plays an

important role in managing these patients. Unfortunately there are

different AS protocols with various inclusion criteria, and urologists and

oncologists may have difficulty deciding which protocol to adopt. The gold

standard to answer this question will be a prospective randomised trial to

compare overall survival following the application of different AS

protocols. This, however, will require decades to observe low-risk

prostate cancer patients before survival endpoints are reached. Our study

provides data on pathological outcomes when different AS protocols were

compared.

In our cohort, the proportion of patients eligible

for active surveillance varied widely from approximately 11% to 58%

according to different selection criteria (Table 3). Two recent series showed similar findings

of a large discrepancy in the proportion of patients eligible for

different AS protocols, varying from 16% to 63% and 28% to 69%.18 19 We

demonstrated that although all AS protocols aim to select low-risk

prostate cancer, the heterogeneity between them can be quite large.

Clinicians need to be vigilant before adopting any of the AS protocols for

their patients when further data from comparative analyses among different

protocols are unavailable. The proportion of patients who were eligible

for AS protocols in our study was lower than that in previous series.18 19 This may

be because some patients with localised prostate cancer were treated with

radiotherapy. The proportion of patients who can be selected in different

AS protocols will be affected by the proportion of patients who undergo

radiotherapy instead of surgery. In our centre, it is also possible that

low-risk patients were selected to undergo a non-operative approach.

When the six protocols were compared after

stratifying patients according to different AS criteria, the University of

Toronto protocol had a significantly higher rate of extracapsular

extension at 17.1% and pathological T3 disease at 19.1% than the John

Hopkins protocol (3.3% extracapsular extension, P=0.05 and 3.3%

pathological T3 disease, P=0.03) and PRIAS criteria (8.0% pathological T3

disease, P=0.04) [Table 5]. This observation can be explained by the

difference in stringency of the two protocols. The University of Toronto

criteria selected patients by two factors only: PSA of <10 ng/mL and

Gleason score of ≤6; PSA density, number of positive biopsy cores, and

percentage of core involvement were not considered. On the contrary, the

John Hopkins criteria applied very strict criteria: a PSA density of 0.15

ng/mL/mL. In addition, only patients with T1 disease with at most two

positive cores during biopsy and no more than 50% involvement of each core

were selected (Table 1). Contrary to our findings, El Hajj et al19 found no significant difference

in the rate of extracapsular extension, upgrading of Gleason score, or

unfavourable disease when they compared the University of Toronto protocol

with the John Hopkins protocol. The difference can be explained by the

high rate of extracapsular extension (15%) and unfavourable disease (46%)

within the John Hopkins criteria in their series, compared with 3%

extracapsular extension and 3% pathological T3 disease in our cohort. This

also implies that disease heterogeneity among different populations may

influence the choice and results of different AS protocols.

In our study, analyses of final pathology revealed

that the Royal Marsden protocol had a significantly higher rate of

upgrading of Gleason score at 34.5% compared with the PRIAS criteria at

20.6% (P=0.04; Table 5). This result can be explained by the

less-stringent selection criteria of the Royal Marsden protocol. First, it

is the only protocol that allowed a Gleason score of 3+4 to be selected.

Second, PSA level up to 15 ng/mL was permitted. These factors will

invariably result in the inclusion of a proportion of patients with

higher-risk disease. In the study by El Hajj et al,19 the Royal Marsden protocol were compared with the

John Hopkins protocol and significantly more unfavourable disease was

observed in the Royal Marsden group. Klotz et al11

also demonstrated that inclusion of Gleason score of 4 on biopsy into AS

was a risk factor in predicting definitive treatment during active

surveillance. These findings illustrate that active surveillance in

patients with Gleason score of 3+4 is likely to miss higher-risk disease.

It should be used cautiously and preferably not in young patients who are

otherwise fit for radical treatments.

We have shown that less pathological T3 disease and

Gleason score upgrading were present in the more-stringent John Hopkins

and PRIAS protocols compared with the less stringent University of Toronto

and Royal Marsden criteria. Nonetheless their sensitivity in identifying

low-risk disease may be compromised by the more stringent selection

criteria. More low-risk disease may therefore be excluded from

surveillance by these stringent criteria. We addressed this issue in the

last part of our analyses. The sensitivity and specificity in identifying

localised disease (pathological stage <T3) and low-risk histology (no

upgrading of Gleason score) among different AS protocols were compared (Table 6). The most stringent protocols of the John

Hopkins and PRIAS had the highest specificity when selecting localised

disease (94%-98%) and low-risk histology (91%-94%). However, inclusion of

less pathological T3 disease and Gleason score upgrading by the more

stringent protocols of John Hopkins and PRIAS should be cautious because

it will, inevitably, be at the expense of low-risk patients who is

excluded from AS and may receive unnecessary aggressive treatments. A

recent study by Iremashvili et al18

showed that the PRIAS criteria had a better balance of sensitivity and

specificity compared with the UCSF and MSKCC criteria. From our point of

view, we tend to place more emphasis on high specificity since low

specificity will include patients with high-risk tumours into active

surveillance and thus patient survival may be jeopardised.

The present study had several limitations. First,

the number of biopsy cores was not consistent throughout the study period.

A proportion of patients had six-core biopsies in the early period of the

cohort versus the current more recent standard of 10-12–core biopsies.

Second, the sample size was relatively small due to the low incidence of

prostate cancer in our population. Third, the tumour volume in

prostatectomy specimens that might predict low-risk prostate cancer was

not assessed. Lastly, the final prostatectomy pathology in this study was

from patients who were operated on soon after diagnosis and not after a

period of post-diagnosis surveillance. As a note of caution, it would be

expected that the final pathology would show even worse pathological

features if the patients were put on AS and operated on later. This should

be noted when interpreting the results of the current study and

counselling patients.

In conclusion, there is a wide range of variation

in the selection criteria of different AS protocols. Active surveillance

protocols based on PSA and Gleason score alone or including Gleason score

of 3+4 may miss higher-risk disease and should be applied cautiously. The

more stringent criteria of John Hopkins protocol and the PRIAS protocol

were highly specific in identifying localised disease and low-risk

histology.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest

References

1. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et

al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European

study. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1320-8. Crossref

2. Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL 3rd,

et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening

trial. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1310-9. Crossref

3. Ploussard G, Epstein JI, Montironi R, et

al. The contemporary concept of significant versus insignificant prostate

cancer. Eur Urol 2011;60:291-303. Crossref

4. Etzioni R, Penson DF, Legler JM, et al.

Overdiagnosis due to prostate-specific antigen screening: lessons from

U.S. prostate cancer incidence trends. J Natl Cancer Inst

2002;94:981-90. Crossref

5. Novara G, Ficarra V, Rosen RC, et al.

Systematic review and meta-analysis of perioperative outcomes and

complications after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol

2012;62:431-52. Crossref

6. Boorjian SA, Eastham JA, Graefen M, et

al. A critical analysis of the long-term impact of radical prostatectomy

on cancer control and function outcomes. Eur Urol 2012;61:664-75. Crossref

7. Zaorsky NG, Harrison AS, Trabulsi EJ, et

al. Evolution of advanced technologies in prostate cancer radiotherapy.

Nat Rev Urol 2013;10:565-79. Crossref

8. Bastian PJ, Carter BH, Bjartell A, et

al. Insignificant prostate cancer and active surveillance: from definition

to clinical implications. Eur Urol 2009;55:1321-30. Crossref

9. Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L.

Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin

Oncol 2011;29:3669-76. Crossref

10. Dall’Era MA, Albertsen PC, Bangma C,

et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the

literature. Eur Urol 2012;62:976-83. Crossref

11. Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, Nam R,

Mamedov A, Loblaw A. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large,

active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol

2010;28:126-31. Crossref

12. van As NJ, Norman AR, Thomas K, et al.

Predicting the probability of deferred radical treatment for localised

prostate cancer managed by active surveillance. Eur Urol

2008;54:1297-305. Crossref

13. Carter HB, Kettermann A, Warlick C, et

al. Expectant management of prostate cancer with curative intent: an

update of the Johns Hopkins experience. J Urol 2007;178:2359-64. Crossref

14. Tosoian JJ, Trock BJ, Landis P, et al.

Active surveillance program for prostate cancer: an update of the Johns

Hopkins experience. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2185-90. Crossref

15. Dall’Era MA, Konety BR, Cowan JE, et

al. Active surveillance for the management of prostate cancer in a

contemporary cohort. Cancer 2008;112:2664-70. Crossref

16. Berglund RK, Masterson TA, Vora KC,

Eggener SE, Eastham JA, Guillonneau BD. Pathological upgrading and up

staging with immediate repeat biopsy in patients eligible for active

surveillance. J Urol 2008;180:1964-7. Crossref

17. van den Bergh RC, Roemeling S, Roobol

MJ, Roobol W, Schröder FH, Bangma CH. Prospective validation of active

surveillance in prostate cancer: the PRIAS study. Eur Urol

2007;52:1560-3. Crossref

18. Iremashvili V, Pelaez L, Manoharan M,

Jorda M, Rosenberg DL, Soloway MS. Pathologic prostate cancer

characteristics in patients eligible for active surveillance: a

head-to-head comparison of contemporary protocols. Eur Urol

2012;62:462-8. Crossref

19. El Hajj A, Ploussard G, de la Taille

A, et al. Patient selection and pathological outcomes using currently

available active surveillance criteria. BJU Int 2013;112:471-7. Crossref

A video clip showing frameless

stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases is available at

A video clip showing frameless

stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases is available at