Exploration of clinical and ethical issues in an expanded newborn metabolic screening programme: a qualitative interview study of healthcare professionals in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Med J 2024 Apr;30(2):120–9 | Epub 9 Apr 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Exploration of clinical and ethical issues in an expanded newborn metabolic screening programme: a qualitative interview study of healthcare professionals in Hong Kong

Olivia MY Ngan, PhD1,2; Ching Janice Tam, MSc (Medical Genetics), BNurs3; CK Li, MD, FRCPCH4,5

1 Medical Ethics and Humanities Unit, School of Clinical Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Centre for Medical Ethics and Law, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Hong Kong Hub of Paediatric Excellence, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Olivia MY Ngan (olivian1@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The Newborn Screening Programme

for Inborn Errors of Metabolism (NBSIEM) enables

early intervention and prevents premature mortality.

Residual dried bloodspots (rDBS) from the heel prick

test are a valuable resource for research. However,

there is minimal data regarding how stakeholders

in Hong Kong view the retention and secondary use

of rDBS. This study aimed to explore views of the

NBSIEM and the factors associated with retention

and secondary use of rDBS among healthcare

professionals in Hong Kong.

Methods: Between August 2021 and January 2022,

semi-structured interviews were conducted with 30

healthcare professionals in obstetrics, paediatrics,

and chemical pathology. Key themes were identified

through thematic analysis, including views towards

the current NBSIEM and the retention and secondary

use of rDBS.

Results: After implementation of the NBSIEM,

participants observed fewer patients with acute

decompensation due to undiagnosed inborn errors

of metabolism. The most frequently cited clinical

utilities were early detection and improved health

outcomes. Barriers to rDBS storage and its secondary use included uncertain value and benefits, trust

concerns, and consent issues.

Conclusion: This study highlighted healthcare

professionals’ concerns about the NBSIEM and

uncertainties regarding the handling or utilisation of

rDBS. Policymakers should consider these concerns

when establishing new guidelines.

New knowledge added by this study

- After implementation of the Newborn Screening Programme for Inborn Errors of Metabolism, participants observed fewer patients with acute decompensation due to undiagnosed inborn errors of metabolism.

- The obligation to know more about a child’s health and the drive for an altruistic contribution to science were factors supporting the retention of residual dried bloodspots (rDBS) for secondary research use.

- Uncertain value and benefits of rDBS, along with concerns regarding trust, privacy, and consent, were cited as barriers to the retention of rDBS for secondary research use.

- The retention of rDBS requires inherent trust based on public support, with strict clinical and ethical parameters.

- Concerns about privacy and consent issues related to genomic information should be addressed before next-generation sequencing is integrated into clinical care for newborns.

Introduction

Inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) are rare genetic

diseases arising from congenital deficiencies of

certain enzymes or cofactors. The accumulation

of excessive toxic substances and the absence of

essential metabolites may damage vital organs,

impair normal metabolism, or increase risks of morbidity and mortality. A small proportion of IEM

cases can be diagnosed and treated early through

dietary interventions. Patients substantially benefit

from early diagnosis and appropriate disease

monitoring.

The incidence of IEM in Hong Kong is 1 in 1682 newborns.1 In response to public health concerns, a territory-wide free voluntary Newborn

Screening Programme for IEM (NBSIEM) was

implemented for all newborns born in public

birthing units, beginning in 2017.2 This programme

covers 27 conditions, including severe combined

immunodeficiency (SCID).3 Spots of blood are

collected from newborns within 24 to 72 hours after

birth, preferably following 24 hours of milk feeding,

using a heel prick test; these samples are discarded

after hospital laboratories perform quality control

and assurance monitoring (online supplementary Table 1).

The materials on dried bloodspots provide

clinical benefits and lifelong healthcare research

opportunities that are advantageous to individuals

and the population. However, the retention and

use of residual DBS (rDBS) has led to controversies

regarding privacy, transparency, consent, misuse

of, and unauthorised access to information,

unclear research purposes, and the absence of data

management and governance protocols.4 Despite

these concerns, it is common for rDBS to be routinely

stored and used for research purposes in some

regions. For example, in Denmark, a nationwide

newborn screening programme was implemented in

1975; it currently screens for 17 diseases.5 Samples

are stored indefinitely with consent in the Danish

Newborn Screening Biobank at the State Serum

Institute.6 Similarly, a programme in the Netherlands

screens for 31 conditions.7 Although participation is

voluntary, the participation rate has reached 99.3%.8 In the Netherlands, rDBS samples are stored for

1 year to facilitate quality control. Most samples

are stored for an additional 4 years for secondary

uses, such as disease-specific biomedical research

and patient-specific diagnostic purposes, after the

acquisition of parental consent.9 The International

Society for Neonatal Screening compared national

newborn screening policies, revealing great variation

in programme acceptance, consent procedure,

storage, and length of storage.8 The Society’s findings

highlight the importance of incorporating local

views during policy development.

Two empirical studies in Hong Kong revealed

that parents were unaware of the expanded newborn

screening programme and the potential value of

rDBS.10 11 The secondary use of rDBS in medical and

health research is well-supported, mainly on the basis

of altruism. However, participation does not provide

direct individual benefits. Factors contributing to

parental support towards retention and secondary

use of rDBS include parental consent and trust

in the relevant authority. If explicit permission is

obtained, parents are more willing to contribute

their child’s rDBS card. An opt-out approach and

broad consent for unspecified use were considered

unfavourable options.11 Although multiple rDBS-focused

studies in Hong Kong have included public

stakeholders, few have assessed the attitudes of

healthcare professionals (HCPs)12; none have been

conducted since implementation of the territory-wide

screening programme. To address this gap, the

present study explored views of the NBSIEM and the

factors associated with retention and secondary use

of rDBS cards among HCPs in Hong Kong.

Methods

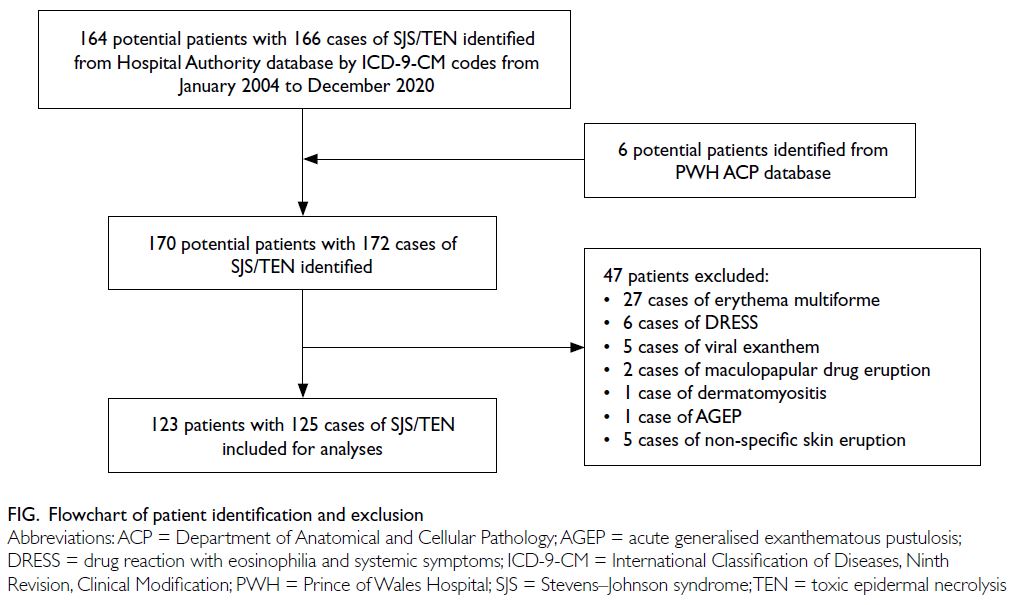

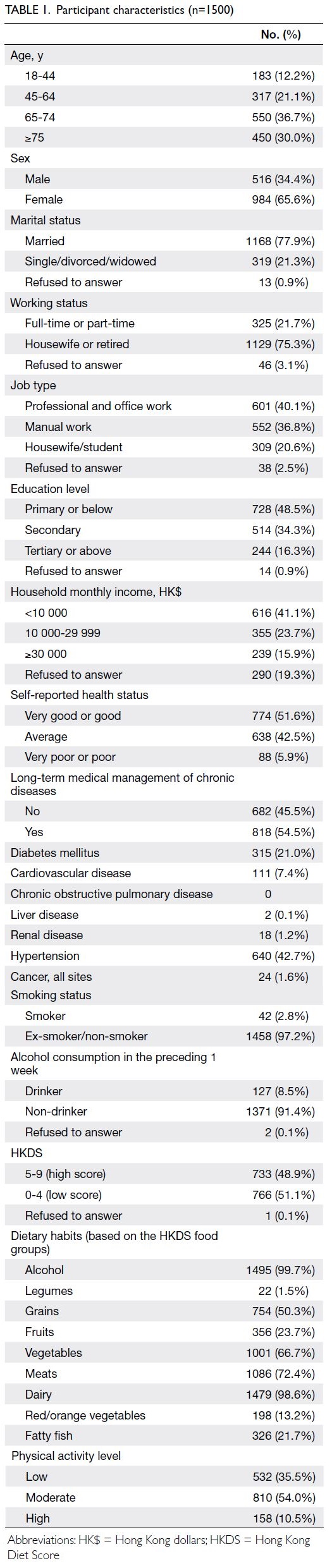

Sampling and recruitment

Semi-structured interviews were conducted among

30 HCPs in obstetrics, paediatrics, and chemical

pathology practising in eight public and two private

institutions in Hong Kong between August 2021 and

January 2022. Purposeful sampling was used to select

key stakeholders involved in the NBSIEM according

to disciplines and responsibilities. Initial invitations

were sent through the two local medical universities

(ie, The University of Hong Kong and The Chinese

University of Hong Kong) and associated hospitals.

Referrals via snowballing were also performed to

recruit additional participants.

The study inclusion criteria were academics

and HCPs (eg, medical, nursing, and laboratory

staff) involved in IEM-related research or clinical

work. Individuals who did not meet the criteria were

excluded. Overall, this study recruited participants

who were involved in recruitment and counselling

within the NBSIEM, laboratory data analysis and

interpretation, or academic research related to IEM.

Each participant received a detailed

description of the research. All participants gave

written informed consent before taking part in the

study. The second author conducted the interviews

at locations convenient for participants, such as

meeting rooms, offices, and coffee shops. The

interview length ranged from 37 to 71 minutes.

Upon completion of the interview, each participant

received a supermarket voucher for HK$200.

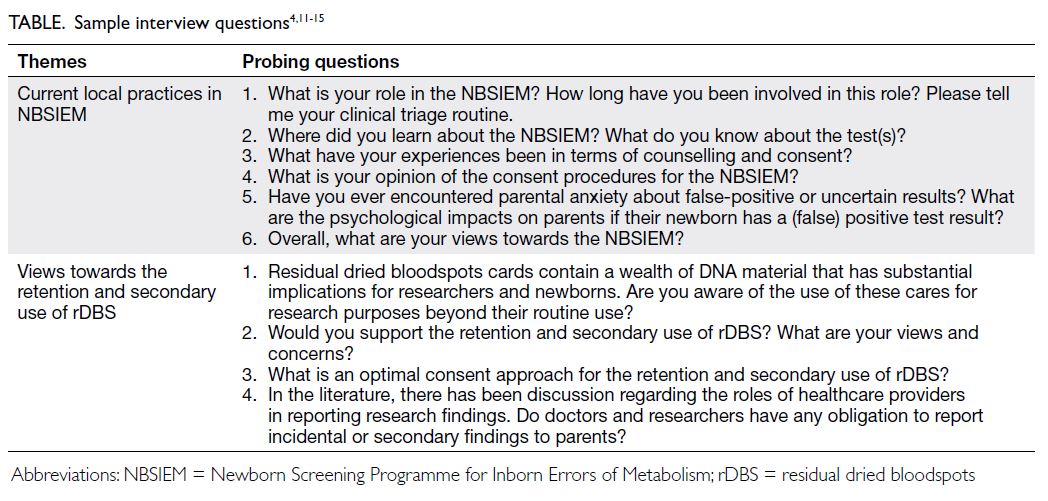

Interview guide

A semi-structured topic guide was developed based

on existing literature concerning newborn screening

and ethical considerations (Table).4 11 12 13 14 15 Prior to

data collection, the guide was reviewed by a senior

paediatrician to ensure its content validity, relevance,

clarity, and cultural sensitivity.

Data analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed

verbatim in the original language (Cantonese),

and then translated into English. Transcripts

were anonymised and assigned an identification

code. The interviewer and another member of the

research team reviewed the transcription accuracy.

Two independent researchers read and coded

the transcripts and audio recordings via thematic

analysis, in which textual data were coded and labelled

in an inductive manner. New thematic codes that did

not fit into predetermined categories were created

and refined, as necessary. Codes were compared

and discussed among research members until a

consensus was reached. Reflexivity was maintained

during the discussion and data analysis process. The

entire research team identified emerging themes

from the early and intermediate stages of interviews,

then recruited HCPs to represent each new theme until theoretical saturation was achieved (ie, no new

themes emerged in the discussions and existing

themes were consistently observed).

Results

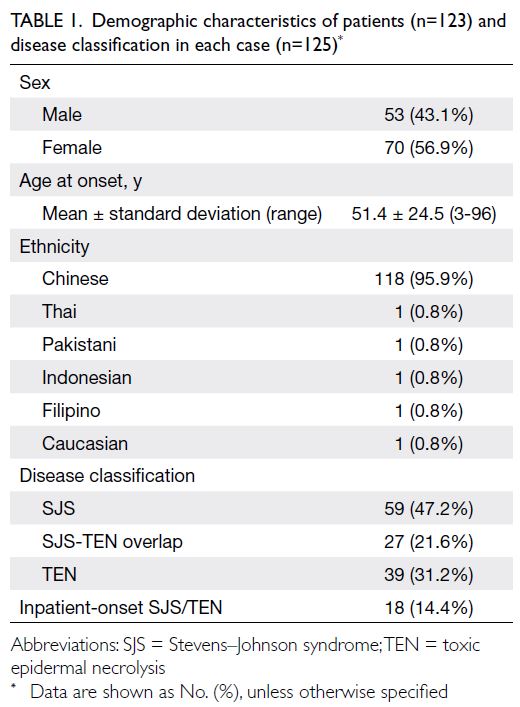

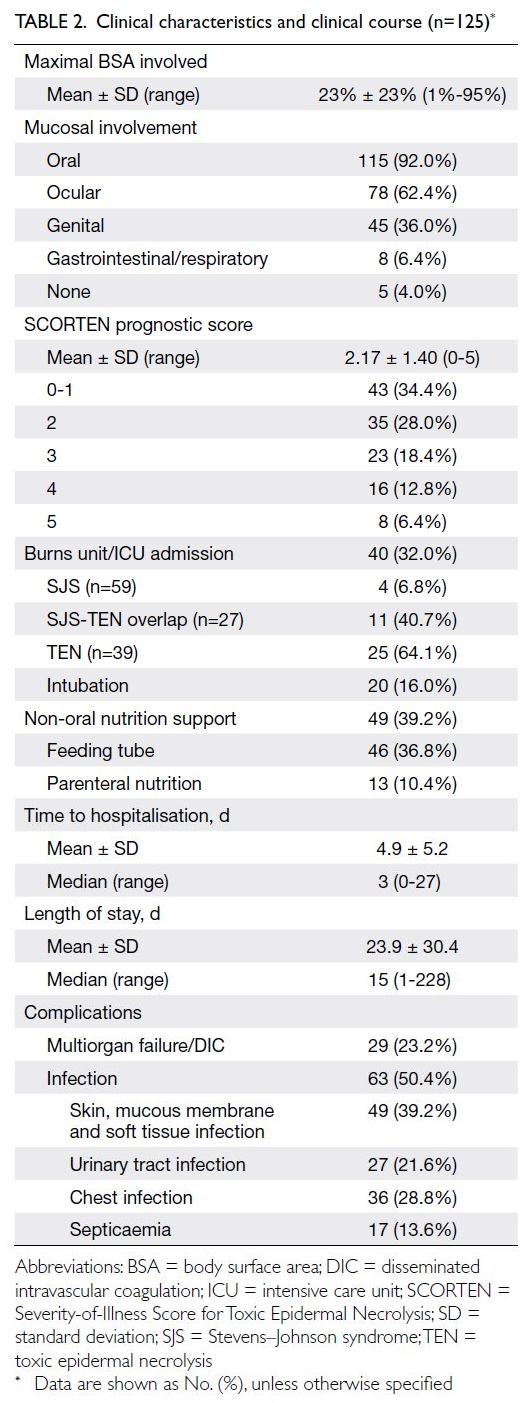

Interviewee characteristics

Thirty HCPs were recruited and interviewed. The

study sample was diverse. Among the interviewees,

15 (50.0%) were doctors and 13 (43.3%) were nurses

or midwives; 13 (43.3%) worked in obstetrics and

gynaecology and 13 (43.3%) worked in paediatrics;

28 worked in the public sector (93.3%); and 14

(46.7%) had >10 years of clinical experience (online supplementary Table 2). Two major thematic themes

were identified, namely, views towards the current

NBSIEM and views towards the retention and

secondary use of rDBS. Illustrative quotations are

used to support the themes.

Theme 1: views towards the current newborn

screening programme

Perceived clinical utility

The implementation of the NBSIEM was a public

health achievement, and interviewees showed a

positive attitude towards the programme. Early

detection and improved health outcomes were the

most commonly reported clinical utility outcomes

(n=21, 70.0%). Some interviewees, primarily

paediatric HCPs, noted a difference between

the periods before and after territory-wide test

implementation. Before NBSIEM, it was not

uncommon for doctors working in intensive care

units to encounter cases of acute decompensation

due to undiagnosed IEM. Considering the broad

phenotypes involved in IEM, such conditions may

not be recognised in early stages.

‘I have been working in the ward for ages and

observed that many patients with IEM deteriorated

to an irreversible stage. With this NBSIEM, we

can screen out IEM cases and offer treatment. The

patients achieve normal development like others.

In other words, the screening helped many people.’

(Interview 25, paediatric nurse)

Affected families previously endured a long

wait for diagnosis before the NBSIEM; there was a

substantial psychological burden involved. Parental

distress was observed.

‘From hospital admission to disease diagnosis,

it takes 2 weeks. The whole process involved hospital

transfer from the (suspected IEM clinic) to the

specialised team at (Hong Kong) Children’s Hospital,

conducting blood investigation, and making a

diagnosis.’ (Interview 20, paediatric doctor)

Some limitations were noted, including false-positive

and false-negative results, as well as call-back

rates. Interviewees cited the reduction of

recall caseloads as an advantage associated with

implementation of second-tier tests.

‘It is best if we can eliminate the false-positives.

To achieve this purpose, we implement aggressive

second-tier testing. Our pathologists also make

stringent interpretations. Without pathologists

working in laboratories, clinicians can only draw

reference from the pre-set levels.’ (Interview 30,

pathology doctor)

Screening panel

The programme covers 27 conditions, including

SCID.3 Interviewees generally agreed that the

benefits of screening for lethal IEM conditions

outweigh the costs of screening, despite the very low

incidence of IEMs. When asked about their views

on the current panel, interviewees emphasised that

disease selection must be based on public health

principles, supported by Wilson and Jungner’s

screening criteria.16 Diseases in the panel should be

treatable and have a high prevalence in Hong Kong.

‘I support the NBSIEM. I believe (the experts)

came up with the 27 conditions based on robust

considerations, including incidence and prevalence,

availability of treatment, mortality prevention, cost-effectiveness,

etc. It is beneficial to patients.’ (Interview

13, obstetrics and gynaecology doctor)

Healthcare professionals have encountered

parents who have completed the publicly funded

IEM test and selected an additional private IEM test

solely based on the number of conditions. For such

parents, the underlying motivation is that ‘screening

more conditions is perceived to be more definitive’.

If I were a mother with a child, I would like to

know whether my child was affected by these diseases.

The more conditions the panel includes, the better.

One can prevent the onset of disease. Parents are

helpless when diseases occur suddenly.’ (Interview 24, obstetrics and gynaecology doctor)

‘Some mothers compared the list of conditions

between the public and private sectors. I am talking

about the difference between 26 and 30 conditions,

respectively. They would rather pay out of pocket and

send the baby to retake the test in the private sector.’

(Interview 16, obstetrics and gynaecology academic)

One paediatrician questioned whether a

genetic test with a larger number of conditions

contributes to enhanced parental control and

confidence regarding the newborn’s health. She was

aware of some urine tests available in the direct-to-consumer

market that screen for so-called ‘non-diseases’—short-/branched-chain acyl-coenzyme A

dehydrogenase and 3-methylcrotonyl-coenzyme A

carboxylase deficiency—although such conditions

do not require follow-up. She highlighted the

importance of periodically reviewing conditions

on the panel according to locality-specific factors,

including disease prevalence, clinical sensitivity and

specificity, treatment, and cost-effectiveness.

‘Running an analysis on a rDBS card is not

difficult. What is more challenging is the post-analysis

follow-up. Compared with other NBSIEMs,

the United States screens for the greatest number

of conditions, maybe 40, while the United Kingdom

screens for five conditions. Instead of adding

conditions, should we also consider taking out some

(non-disease) conditions from the list?’ (Interview 27,

paediatric doctor)

Source of information

Three HCPs (10.0%) reported that most Hospital

Authority staff received NBSIEM information

through departmental seminars and training

sessions, which prepared them to complete the

consent procedure with parents. When asked about

their understanding of IEMs, knowledge levels varied

among frontline staff involved in the NBSIEM. Some

were uncertain what the test evaluated.

‘What is it (NBSIEM) testing for…? Is it

checking for chromosomal defects? Or is it checking

for lack of (metabolites)?’ (Interview 15, obstetrics

and gynaecology nurse)

Some also mistakenly thought that the NBSIEM analysed genes.

‘It is a filter paper with some dried bloodspots,

testing IEM genes.’ (Interview 29, obstetrics and

gynaecology doctor)

Some frontline staff wanted additional

information beyond the procedure. They felt

unprepared for questions about the diseases,

symptoms, test procedures, and care for patients

with IEMs. They felt anxious or uncomfortable

explaining these aspects to parents with some level

of understanding.

‘After implementing this programme, what the

patients will undergo, where they will be referred to, what to do with a confirmed diagnosis… to be honest,

I learned everything from the protocol. In actual

settings, parents asked many practical questions,

such as “what to be cautious about during daily

care”—I do not know how to answer them. These are

not common diseases observed in the ward, but we

are asked to counsel parents.’ (Interview 24, obstetrics

and gynaecology doctor)

A senior doctor responsible for providing

educational seminars noted that training should

not be an isolated event; periodic refresher training

should be provided.

‘We provide intensive training for nurses, all of

them. (In the training), we give clear explanations,

conduct videotaping (for review), and address

inquiries and questions. In addition, we also plan

to host refresher courses every few years. Hong Kong

requires more observation before moving forward.’

(Interview 27, paediatric doctor)

Experience with parental counselling and consent

procedure

Interviewees felt that the educational pamphlet and

consent material are easy to read. During parental

counselling, HCPs were prepared to answer parents’

enquiries. Most parents supported the NBSIEM.

Parents wanted to identify IEM conditions in their

newborns because they felt that early detection

could facilitate autonomous decision-making related

to their child and other family members.

‘I observed that most parents enrol in the

NBSIEM as they would like to know sooner if their

babies are affected. If a diagnosis is confirmed, we run

a genetic test to predict the risk of recurrence. Only a

few refuse to take part in the programme.’ (Interview

23, paediatric doctor)

Midwives played an important role in obtaining

parental consent in antenatal clinics. Refusals of

the current NBSIEM are infrequent. Five frontline

staff (16.7%) involved in the recruitment process

observed that only a small number of parents, who

were sceptical about medical interventions or had

religious affiliation–based reservations, declined to

join the programme.

‘Some people who advocate minimal

medicalisation do not consent to procedures in our

hospital. For example, they refuse vaccinations and

vitamin K injections.’ (Interview 10, obstetrics and

gynaecology nurse)

Participants involved in recruitment

recognised that informed consent procedures

were intended to enable parents to make informed

choices. The current opt-in consent approach allows

HCPs to obtain explicit permission from parents.

The participants observed that parents, especially

Hong Kong Chinese individuals, were vocal about

the patient’s right to know.

‘Nowadays, patients put a strong emphasis on patient’s rights, thinking that “you need my consent before carrying out a procedure".’ (Interview 5,

obstetrics and gynaecology nurse)

In particular, six HCPs (20.0%) speculated that

opt-in consent was more accepted by parents and

thus easier to obtain. It provided parents with a sense

of personal control by allowing them to give explicit

permission. Opt-in consent has been used in many

medical settings. It is more familiar to and accepted

by community members with respect to studies of

genetic material.

‘Must I choose a consent model for handling

genetic materials? It would be an opt-in approach.’

(Interview 6, obstetrics and gynaecology doctor)

Seven HCPs (23%) felt that consent was needed because of the invasiveness of the procedure, but some HCPs felt that the procedure involved minimal harm.

‘(The phlebotomists) perform an invasive

procedure on the infant, which may cause discomfort

or pain. Opt-in is preferable to an opt-out approach.

(Interview 27, paediatric doctor)

‘It is just a heel prick test and will not affect the

baby. I cannot see the downsides (of the screening).’

(Interview 16, obstetrics and gynaecology academic)

Opt-in consent was perceived to be more

efficient. There may be opposition to an opt-out

approach. Some HCPs (n=6, 20.0%) felt that an

opt-out approach would increase sample sizes and

contribute to advances in medical research.

‘Inborn errors of metabolism would be a

prevalent issue, and therefore, opt-out is better than the

opt-in approach. Like an human immunodeficiency

virus test with an opt-out approach, one can refuse to

take the test for a valid reason. There are treatments

for IEMs; opt-out is a desirable consent model.’

(Interview 24, obstetrics and gynaecology doctor)

One doctor pondered the adoption of different

methods in obtaining informed consent because

opt-in and opt-out approaches are ‘like two sides

of the same coin’. He stated that the key aspect of

selecting an appropriate consent approach is the

parental counselling process. He also emphasised

that the consent procedure is not absent from the

opt-out approach and that effective communication

remains important.

Disclosure of confirmed results of inborn errors of

metabolism to affected families

When a confirmed IEM diagnosis was disclosed to an

affected family, parents often felt shocked, stressed,

and guilty about having an ‘abnormal’ baby. They

then began to explore the financial implications; for

example, some worried about treatment costs and

uncertainties. Counselling is limited to discussing

the diagnosis; it also includes psychological support

through follow-up care involving a multidisciplinary

team.

‘Many families were worried when they heard

about the IEM diagnosis, as they knew it was a life-long

condition. It is tough to handle (bad news). Their

child will be different from other peers, and finances

will be affected. They must self-finance the drugs.’

(Interview 28, paediatric nurse)

On some occasions, the NBSIEM is beneficial

to the newborn and has implications for the entire

family. Some interviewees reported disclosing an

IEM result relevant to the mother, rather than the

infant. In one case, the HCP informed the involved

family members and provided follow-up care for the

newborn’s siblings.

‘Sometimes, a secondary finding is related to

the mother instead of the child. When maternal blood

contamination is present (the baby is not affected),

the mother is referred to relevant specialists for

medical follow-up.’ (Interview 23, paediatric doctor)

‘We had a positive result for citrullinemia

deficiency. The newborn had three brothers and a

sister with the same disease. Now we are following

them.’ (Interview 27, paediatric doctor)

Theme 2: acceptance of retention and secondary use of residual dried bloodspots

Motivations for storage

Interviewees were asked about their views of rDBS

storage. Healthcare professionals supported the

long-term storage of rDBS through the NBSIEM to

facilitate advances in public health epidemiology,

forensic purposes, familial disease analysis, and

development of other screening tests. Some HCPs

highlighted the importance of rDBS in supporting

scientific advances. Stored rDBS could be used to

enhance healthcare management and clinical testing,

such as establishment of local reference standards.

‘We did not know how to define the cut-off values

at first. Within the United States, the cut-off values

differ by state. The initial cut-off values we chose may

not reflect local needs. Residual dried bloodspots

(storage) is essential to develop a large data pool that

supports a control pool when technology advances.’

(Interview 19, pathology doctor)

Healthcare professionals observed that

most parents demonstrated substantial interest in

knowledge about their children. They thought that

parents would like to have the right to obtain medical

information regarding their children.

‘I believe that most parents would agree to save

(their) genetic material...perhaps... they would not

mind if the laboratory preserved the DNA material

and let them know the findings of future screening

tests.’ (Interview 17, paediatric doctor)

Barriers to storage

Uncertain value of retention

Four HCPs (13.3%) were worried that the public lacked an understanding of how rDBS could generate

knowledge. This lack of awareness may be linked to

an unwillingness among parents to permit the use of

their children’s rDBS samples.

‘Many laypeople may not understand why

they should engage in research studies. They may be

reluctant to take part in research studies due to their

own beliefs.’ (Interview 3, obstetrics and gynaecology

nurse)

Two-fifths of HCPs (n=12) questioned the need for the long-term storage programme.

‘Several ongoing studies on population

genetics use a wide-consent approach, supported by

government funding. Does every newborn have to

provide data (to support this research)? I doubt it.’

(Interview 18, paediatric doctor)

‘With strong opposition, I dissent to the storage

(of rDBS) as I see no value at all. Perhaps it offers

convenience for research, but it provides no personal

benefits.’ (Interview 30, pathology doctor)

Interviewees believed that genetic material is

very stable and does not easily degrade, despite long

storage periods. Although storage is possible, some

concerns were raised about its cost-effectiveness.

‘I heard researchers (scientists) mention that

proper sample storage incurs a considerable cost.’

(Interview 13, obstetrics and gynaecology doctor)

No direct benefit to patients or parents

Around one-fourth of HCPs (n=7, 23.3%) would

only support clinical research if the findings could

be used to help their children and patients. Parents

were not expected to be interested in research,

especially if it did not provide direct clinical benefit

to their children.

‘Parents care about whether the disease can

be treated or not. Knowledge of disease aetiology is

only relevant to public health or research institutes.’

(Interview 2, obstetrics and gynaecology nurse)

‘Would I receive the data if I donated a sample?

I would donate a sample if the researcher would

return the data. I must know every single conclusion

or diagnosis from data generated using the rDBS. I

would refuse if no data were returned.’ (Interview 13,

obstetrics and gynaecology doctor)

Trust and privacy concerns regarding responsible

authorities

Another recurring theme was trust in the context of primary privacy concerns, such as data leakage

and misuse of private information generated from

sensitive genetic materials.

‘It may not be desirable to store (genetic

materials) for a long time. The longer it is stored, the

more concerns arise. Immediate disposal would be

more reassuring in terms of the protection of privacy.’

(Interview 12, paediatric nurse)

‘Some people may steal genetic information

(rDBS cards) for illegal (or unauthorised) purposes.’

(Interview 12, paediatric nurse)

Obligation to return research findings

Generally, around 30% of the interviewed doctors and

researchers (n=9) believed they have a duty to warn

research participants upon finding abnormalities,

enabling parents to take appropriate action after

receiving relevant test results, including secondary

findings.

There is an obligation to inform the patients

(of medically actionable findings) because we work in

this profession. First, we do no harm. If a significant

finding warrants medical attention, we should be

responsive and responsible.’ (Interview 24, obstetrics

and gynaecology doctor)

Issues with obtaining consent for storage purposes

The importance of consent was acknowledged, but

there was disagreement concerning the need for

broad or specific consent. Interviewees frequently

noted that broad consent is convenient for

researchers.

‘Our understanding of IEMs or diagnostic tests

increases as time goes by. The advantage of broad

consent is that we do not need to obtain consent

when new technology evolves. Like the recently added

SCID, we do not need to redesign or implement a new

consent procedure again when adding new conditions

to the panel.’ (Interview 9, paediatric doctor)

Despite the view that broad consent may permit

more efficient use of biospecimens and relevant data,

there were concerns about public acceptance. Some

interviewees stated that it would be challenging to

obtain consent for all future research and explain the

need for a change in consent approach.

‘Broad consent implies uncertainty in the

research scope, which leads to parental concern.

Parents are uncertain how the rDBS will be used

or handled. I feel uneasy during counselling. I am

not sure how their blood will be used in a research

project, but in short, it will be helpful.’ (Interview 7,

paediatric doctor)

‘Broad consent entails an unknown. As such,

parents might be unwilling to sign the consent form

(and contribute the rDBS).’ (Interview 27, paediatric doctor)

For HCPs, the legitimacy and scope of consent

are key considerations. Specific consent is commonly

exercised in clinical or research procedures in Hong

Kong. It is recognised as the most appropriate

procedure because it ensures patients receive

information about the study. A few interviewees

mentioned that no existing framework recommends

the use of broad consent; thus, they favoured the use

of specific consent.

‘Specific consent may not provide sufficient coverage of all possible research. If there is a breach

in the protocol, it may bring about ethical and legal

issues.’ (Interview 26, obstetrics and gynaecology doctor)

‘I found that specific consents were more

protective for HCPs.’ (Interview 15, obstetrics and

gynaecology nurse)

‘I have never sought ethical approval for broad

consent from institutional research boards.’ (Interview

28, paediatric nurse)

The level of public knowledge regarding

the NBSIEM requires further analysis. Education

and counselling might be intended to address

problems that arise from long-term storage. One

doctor emphasised that proper counselling on tests

involving genetic material should be considered best

practice. Some interviewees expressed a desire to

prepare themselves to address parents’ concerns.

‘The drawbacks of the NBSIEM should be

discussed, apart from privacy and personal genetic

information. Parents should be aware that there

are many unknowns in genetics. (As medical

professionals) we have, of course, fewer concerns.

Suppose I have to conduct genetic counselling for an

IEM test. In that case, I will cover all the aspects,

including the basic understanding of genetics, even if

it is a selected target gene panel. I do not see much

difference in terms of counselling across all forms of

genetic tests.’ (Interview 9, paediatric doctor)

Discussion

This study explored the voices of HCPs from

various backgrounds and discussed clinical and

ethical issues during the early implementation

phase of the NBSIEM. Similar to professionals in

the United Kingdom,13 HCPs in Hong Kong did not

exhibit extensive knowledge and awareness of IEM

conditions, which may have detrimental effects

on patient-centred care. First, parental autonomy

might be undermined because parents are not

adequately informed about the test procedure

and conditions. Second, a lack of understanding

regarding IEMs can lead to suboptimal clinical care.

Children with IEMs attend multiple specialist clinics

to manage multiple co-morbidities. Caregivers

encounter difficulties, such as miscommunication

or inconsistent information about medications or

dietary restrictions, when attending non–IEM-specific

clinics.14 They face numerous psychosocial

challenges in caring for their children,15 17 and

increased awareness of these stressors among

healthcare providers could improve communication

for the entire family. More than four-fifths of

individuals in Hong Kong attend medical services

at public hospitals,18 and many parents are expected

to participate in the NBSIEM. The establishment

of training or educational interventions and

a centralised pipeline to coordinate care are essential considerations for patient-centred care

that focuses on caregivers of children with IEMs.

Because hospitals are expanding screening for other

uncommon disorders, such as SCID,19 the results of

the present study may inform the development of a

family-oriented framework for IEM management.

Development of the current NBSIEM was

based on a stringent infrastructure and second-tier

testing pipeline.20 Samples with borderline or

ambiguous results were sent for further genetic tests

to confirm the diagnosis and carrier status. Carnitine

deficiency, citrin deficiency, methylmalonic

acidaemia, and glutaric aciduria type I are examples

of diseases with relatively high incidences of

false-positives or false-negatives.1 21 After the

implementation of stringent second-tier tests, the

recall rate has declined to 0.3% to 0.4%, similar to

the standards of international IEM programmes.22

This work has been successful, and the retention of

rDBS to create a large-scale genetic biobank will be

the next focus of public health dialogue.

It is important to note that territory-wide

biobanks are not common; biobank platforms in

Hong Kong currently are operated by individual

hospitals or institutions. A notable example is

Children of 1997, a population-based birth cohort

study of local infants.23 Other existing platforms

include disease-oriented biobanks,24 which support

quality assurance and conduct epidemiology studies;

they also identify risk factors, novel molecular

markers, and genetic variants associated with diabetes

and related complications. The establishment of

biobanks at separate institutions has led to non-standardised

informed consent practices. Many

ethical and legal issues remain unresolved in efforts

to harmonise all regional biobanks. Public awareness

of the value of rDBS has been low11; improvements

in public acceptance and engagement are needed for

broad support of rDBS storage or biobanks.

The present study highlighted common ethical,

legal, and social concerns as barriers to the storage of

rDBS. Trust and low awareness of the potential value

of rDBS were cited as primary barriers. In contrast

to the assumptions of HCPs, parents generally agree

with academic researchers and doctors accessing their

children’s rDBS and health data after explicit consent

has been provided.11 The optimal consent model

for the use of rDBS outside of screening purposes

depends on cultural and social characteristics that

vary among regions. In the past three decades, some

countries have stored rDBS without consent, leading

to public controversy and lawsuits.25 Considering

these situations, the retention of rDBS requires

inherent trust based on public support, with strict

clinical and ethical parameters. Essential factors

in establishing trust are consent to participate in

the NBSIEM, as well as consent for rDBS retention

and secondary uses; questions remain regarding the optimal approach to obtaining consent.25 Other

factors involved in decision-making concerning

rDBS retention and secondary uses include timing of

consent, adequate communication and discussion of

potential uses, protection of privacy, and responsible

governance.9 11 26 These factors should be considered

in public policy initiatives.

Concerns about privacy issues and

discrimination related to genomic information

will be amplified as next-generation sequencing

is integrated into clinical care for newborns.27 28 In

South Korea, next-generation DNA sequencing

has been evaluated for use in primary newborn

screening.29 In the United Kingdom, Genomics

England plans to offer whole-genome sequencing to

newborns, identifying actionable genetic conditions

that may impact infants in early childhood.30

There is evidence that sequencing data provides

information about conditions not currently assessed

in newborns, as well as information with unclear

clinical significance.29 The previous regime agreed

that it was appropriate to disclose incidental research

findings if they would directly benefit the child after

considering risk and benefit. However, this approach

may differ in cultural and social settings when

considering the child’s future and non-therapeutic

genomic information.

Limitations and strengths of the study

Most participants in this study were HCPs working

in the public sector; they may have different views

regarding clinical utility, value, and perceived cost-benefit,

compared with stakeholders from other

healthcare settings. However, this study used various

sampling strategies to recruit a heterogeneous

group of HCPs with diverse specialities, roles, and

responsibilities in the screening programme, as well

as years of experience. A longitudinal study would

provide long-term insights concerning the NBSIEM.

Knowledge of heterogeneous IEMs and perception

of rDBS storage among HCPs could be analysed via

quantitative methods.

Conclusion

This study highlighted HCPs’ concerns about the

NBSIEM and uncertainties regarding the handling

or utilisation of rDBS. Policymakers should consider

these concerns when establishing new guidelines.

Future investigations should explore parents’

experiences with screening for rare metabolic

conditions and communication of positive results.

Author contributions

Concept or design: OMY Ngan.

Acquisition of data: CJ Tam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: OMY Ngan, CJ Tam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CK Li.

Acquisition of data: CJ Tam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: OMY Ngan, CJ Tam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CK Li.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all healthcare professionals who participated in the study.

Funding/support

This research was supported by the Direct Grant for Research

from the Faculty of Medicine at The Chinese University of

Hong Kong (2020/2021) [Ref No.: 2020.081]. The funder had

no role in study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation

or manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

The research was approved by the Survey and Behavioural

Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of

Hong Kong (Ref No.: SBRE-20-846). All participants provided

written consent for interview and publication of the study.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Any

opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association. The

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical

Association disclaim all liability and responsibility arising from

any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. The Task Force on the Pilot Study of Newborn Screening for

Inborn Errors of Metabolism. Evaluation of the 18-month

“Pilot Study of Newborn Screening for Inborn Errors of

Metabolism” in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Paediatr (new

series) 2020;25:16-22.

2. Belaramani KM, Chan TC, Hau EW, et al. Expanded

newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism in

Hong Kong: results and outcome of a 7-year journey. Int J

Neonatal Screen 2024;10:23. Crossref

3. Hospital Authority. Newborn Screening Programme

for Inborn Errors of Metabolism (IEM). October 2023.

Available from: https://www21.ha.org.hk/smartpatient/SPW/MediaLibraries/SPW/SPWMedia/Education-pamphlet_NBS-IEM_Eng-(Oct-2023).pdf?ext=.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2024.

4. Ngan OM, Li CK. Ethical issues of dried blood spot

storage and its secondary use after newborn screening

programme in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Paediatr (new

series) 2020;25:8-15.

5. Lund A, Wibrand F, Skogstrand K, et al. Danish expanded

newborn screening is a successful preventive public health

programme. Dan Med J 2020;67:A06190341.

6. Nordfalk F, Ekstrøm CT. Newborn dried blood spot

samples in Denmark: the hidden figures of secondary use

and research participation. Eur J Hum Genet 2019;27:203-10. Crossref

7. Jansen ME, Klein AW, Buitenhuis EC, Rodenburg W,

Cornel MC. Expanded neonatal bloodspot screening

programmes: an evaluation framework to discuss new

conditions with stakeholders. Front Pediatr 2021;9:635353. Crossref

8. Loeber JG, Platis D, Zetterström RH, et al. Neonatal

screening in Europe revisited: an ISNS perspective on the

current state and developments since 2010. Int J Neonatal

Screen 2021;7:15. Crossref

9. Jansen ME, van den Bosch LJ, Hendriks MJ, et al. Parental

perspectives on retention and secondary use of neonatal

dried bloodspots: a Dutch mixed methods study. BMC

Pediatr 2019;19:230. Crossref

10. Mak CM, Lam CW, Law CY, et al. Parental attitudes on

expanded newborn screening in Hong Kong. Public Health

2012;126:954-9. Crossref

11. Hui LL, Nelson EA, Deng HB, et al. The view of Hong Kong

parents on secondary use of dried blood spots in newborn

screening program. BMC Med Ethics 2022;23:105. Crossref

12. Mak CM, Law EC, Lee HH, et al. The first pilot study

of expanded newborn screening for inborn errors of

metabolism and survey of related knowledge and opinions

of health care professionals in Hong Kong. Hong Kong

Med J 2018;24:226-37. Crossref

13. Moody L, Atkinson L, Kehal I, Bonham JR. Healthcare

professionals’ and parents’ experiences of the confirmatory

testing period: a qualitative study of the UK expanded

newborn screening pilot. BMC Pediatr 2017;17:121. Crossref

14. Siddiq S, Wilson BJ, Graham ID, et al. Experiences of

caregivers of children with inherited metabolic diseases: a

qualitative study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016;11:168. Crossref

15. Zeltner NA, Landolt MA, Baumgartner MR, et al. Living

with intoxication-type inborn errors of metabolism: a

qualitative analysis of interviews with paediatric patients

and their parents. JIMD Rep 2017;31:1-9. Crossref

16. Petros M. Revisiting the Wilson–Jungner criteria: how

can supplemental criteria guide public health in the era of

genetic screening? Genet Med 2012;14:129-34. Crossref

17. Grant S, Cross E, Wraith JE, et al. Parental social support,

coping strategies, resilience factors, stress, anxiety and

depression levels in parents of children with MPS III

(Sanfilippo syndrome) or children with intellectual

disabilities (ID). J Inherit Metab Dis 2013;36:281-91. Crossref

18. Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority Strategic Plan 2022-2027: Towards Sustainable Healthcare. Available from: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/ap/HA_StrategicPlan2022-2027_Eng_211216.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2021.

19. Leung D, Lee PP, Lau YL. Review of a decade of international

experiences in severe combined immunodeficiency

newborn screening using T-cell receptor excision circle.

Hong Kong J Paediatr (new series) 2020;25:30-41.

20. Tsang KY, Chan TC, Yeung MC, Wong TK, Lau WT,

Mak CM. Validation of amplicon-based next generation

sequencing panel for second-tier test in newborn screening

for inborn errors of metabolism. J Lab Med 2021;45:267-74. Crossref

21. Hennermann JB, Roloff S, Gellermann J, Grüters A, Klein J.

False-positive newborn screening mimicking glutaric

aciduria type I in infants with renal insufficiency. J Inherit

Metab Dis 2009;32 Suppl 1:S355-9. Crossref

22. la Marca G. Mass spectrometry in clinical chemistry: the case of newborn screening. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2014;101:174-82. Crossref

23. Schooling CM, Hui LL, Ho LM, Lam TH, Leung GM. Cohort profile: ‘Children of 1997’: a Hong Kong Chinese birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:611-20. Crossref

24. Ng IH, Cheung KK, Yau TT, Chow E, Ozaki R, Chan JC.

Evolution of diabetes care in Hong Kong: from the Hong

Kong Diabetes Register to JADE-PEARL Program to

RAMP and PEP Program. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul)

2018;33:17-32. Crossref

25. Cunningham S, O’Doherty KC, Sénécal K, Secko D,

Avard D. Public concerns regarding the storage and

secondary uses of residual newborn bloodspots: an

analysis of print media, legal cases, and public engagement

activities. J Community Genet 2015;6:117-28. Crossref

26. Hendrix KS, Meslin EM, Carroll AE, Downs SM. Attitudes about the use of newborn dried blood spots for research: a survey of underrepresented parents. Acad Pediatr

2013;13:451-7. Crossref

27. Pereira S, Robinson JO, Gutierrez AM, et al. Perceived

benefits, risks, and utility of newborn genomic sequencing

in the BabySeq project. Pediatrics 2019;143(Suppl 1):S6-13. Crossref

28. Johnston J, Lantos JD, Goldenberg A, et al. Sequencing

newborns: a call for nuanced use of genomic technologies.

Hastings Cent Rep 2018;48 Suppl 2:S2-6. Crossref

29. Woerner AC, Gallagher RC, Vockley J, Adhikari AN. The

use of whole-genome and exome sequencing for newborn

screening: challenges and opportunities for population

health. Front Pediatr 2021;9:663752. Crossref

30. Biesecker LG, Green ED, Manolio T, Solomon BD, Curtis D.

Should all babies have their genome sequenced at birth?

BMJ 2021;375:n2679. Crossref