Bone health status of postmenopausal Chinese women

Hong Kong Med J 2015 Dec;21(6):536–41 | Epub 16 Oct 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154527

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Bone health status of postmenopausal Chinese women

Sue ST Lo, MD, FRCOG

The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong, 10/F, Southorn Centre, 130 Hennessy Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Sue ST Lo (stlo@famplan.org.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the prevalence of

osteoporosis in treatment-naïve postmenopausal

women, their treatment adherence, and the risk

factors for osteoporosis.

Design: Cross-sectional study of bone density

reports, a self-administered health checklist, and

computerised consultation records.

Setting: Primary care sexual and reproductive health

service in Hong Kong.

Participants: Postmenopausal Chinese women

who had never received osteoporosis treatment or

hormone replacement therapy.

Intervention: Each woman completed a checklist of

risk factors for osteoporosis, menopause age, history

of hormone replacement therapy, and osteoporosis

treatment prior to undergoing bone mineral density

measurement at the postero-anterior lumbar spine

and left femur. The consultation records of those

with osteoporosis were reviewed to determine their

treatment adherence.

Main outcome measures: T-score at the spine

and hip, presence or absence of risk factors for

osteoporosis, and treatment adherence.

Results: Between January 2008 and December

2011, 1507 densitometries were performed for

eligible women; 51.6% of whom were diagnosed with

osteopenia and 25.7% with osteoporosis. The mean

age of women with normal bone mineral density,

osteopenia, and osteoporosis was 57.0, 58.0, and

59.7 years, respectively. Approximately half of them

had an inadequate dietary calcium intake, performed

insufficient weight-bearing exercise, or had too little

sun exposure. Logistic regression analysis revealed

that age, body mass index of <18.5 kg/m2, parental

history of osteoporosis or hip fracture, and duration

of menopause were significant risk factors for

osteoporosis. Among those with osteoporosis, 42.9%

refused treatment, 30.7% complied with treatment,

and 26.3% discontinued treatment or defaulted

from follow-up. Those who refused treatment were

significantly older.

Conclusions: Osteoporosis is prevalent in

postmenopausal women. Only 50% adopted primary

prevention strategies. Almost 70% refused treatment

or stopped prematurely.

New knowledge added by this study

- Osteoporosis affects one in four postmenopausal Chinese women in Hong Kong.

- Age, body mass index of <18.5 kg/m2, a positive parental history of osteoporosis or hip fracture, and duration of menopause are significant risk factors for osteoporosis.

- Only 31% of osteoporotic women complied with the treatment protocol.

- This study showed that osteoporosis is prevalent in Hong Kong Chinese postmenopausal women. Doctors should encourage postmenopausal women to have an adequate calcium intake, perform sufficient weight-bearing exercise, and have enough sun exposure. Those with risk factors should also undergo dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry to ascertain their bone status.

- Drug compliance is a problem in those with osteoporosis. Patient education should be provided to help them understand the importance of treatment compliance, the risk of fracture, and osteoporosis-associated morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a major health problem in the elderly

causing significant morbidity, mortality, and socio-economic

burden. Women are more vulnerable to

osteoporosis than men because they have smaller

and thinner bones. In addition, the sudden drop in

ovarian oestrogen production around menopause

causes women to lose bone rapidly. Accelerated bone

loss begins about 2 to 3 years before the last menses

and continues until 3 to 4 years after menopause.

There is 2% bone loss annually around menopause,

slowing to 1% to 1.5% annually thereafter.1 2 Bone mineral density (BMD) measurement by central

dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the gold

standard for diagnosing osteoporosis. Bone mineral

density is compared with the mean peak BMD

for young adults of the same sex and ethnicity to

calculate a T-score. The World Health Organization

(WHO) defines osteoporosis as a BMD 2.5 standard

deviations (SDs) below that of young-adult BMD and

osteopenia as a BMD 1.0 to 2.5 SD below.3 A meta-analysis

of prospective and case-control studies of

BMD and fracture risk showed that the predictive

value of BMD for fracture is at least as good as that

of blood pressure for stroke.4 In a recent prospective

study of postmenopausal Chinese women, the

relative risk of fracture increased 2-fold (95%

confidence interval [CI], 1.6-2.5) for each decrease

in SD of mean femoral-neck BMD.5

With urbanisation and adoption of a more

sedentary lifestyle, the age-specific incidence of hip

fracture in Hong Kong women increased by 300%

between 1966 and 1985.6 The incidence levelled off

between 1985 and 1995.7 Between 1995 and 2004,

the incidence declined by 50% in those aged 50 to

59 years but remained stable for other age-groups.8

Although the age-specific incidence rates stabilise,

the absolute number of hip fractures will continue

to increase because of the ageing population. It has

been estimated that in Hong Kong, 5293 women

will have a hip fracture in the year 2015.9 The local

prevalence of vertebral fracture in women has

been estimated to be 30%.10 Osteoporotic fractures

increase the morbidity and mortality of individuals

and are a considerable burden on the health-care

system. After the first fracture, the risk of subsequent

fracture of an individual is 2.2 times higher than

that of an individual without a prior fragility

fracture (95% CI, 1.9-2.6).11 Primary care physicians

play a pivotal role in preventing this fracture

cascade in postmenopausal women. They can help

postmenopausal women improve bone health by

encouraging them to adopt primary prevention

strategies for osteoporosis and fall that may cause

fracture; increasing their awareness of their personal

risk for osteoporosis and taking action to minimise

those risks; providing DXA assessment when

indicated; and treating women who are diagnosed

with osteoporosis.12 Pharmacological treatment can

reduce the risk of osteoporotic fractures by 30% to

70%. Treatment failure is partly due to poor drug

compliance with treatment. In a systematic review

of osteoporosis treatment with bisphosphonates,

the yearly drug compliance rate was only 42.5% to

54.8%.13

The objectives of this study were to evaluate

the prevalence of osteoporosis in treatment-naïve

postmenopausal Chinese women, and determine

the risk factors associated with osteoporosis and

treatment compliance in those diagnosed with

osteoporosis. These results will help physicians

understand the bone health status of postmenopausal

Chinese women.

Methods

Postmenopausal women who attend the Women’s

Health Service in Hong Kong for menopause assessment are

offered DXA testing of the spine and hip. Since

a charge is made for the test, it is not universally

accepted. The number of women who refused

DXA was not captured. Prior to undergoing DXA,

women completed a checklist of risk factors that

included a history of parental osteoporosis or hip

fracture, personal low trauma fracture, smoking

habit, drinking habit, calcium intake, exercise

habit, sun exposure, use of medication or presence

of disease that causes bone loss, number of falls

in the past 12 months, previous use of hormone

replacement therapy, previous use of osteoporosis

drugs, and current osteoporosis treatment. The

BMD at the postero-anterior lumbar spine (L1-L4)

and left femur (total hip, trochanter, Ward’s triangle,

and femoral neck) was measured using a Hologic

QDR4000 machine (Hologic Inc, Bedford [MA],

US) and performed by a single operator. The DXA

report provided data on age, menopause age, body

mass index (BMI), BMD, T-score, and Z-score. The

checklist and DXA report were filed together by date.

This analysis was conducted by searching

through paper records completed between January

2008 and December 2011. The research protocol

was approved by the Ethics Panel of the Family

Planning Association of Hong Kong. Non-Chinese

women and those previously or currently prescribed

hormone replacement therapy or osteoporosis

treatment were excluded. The computerised

consultation records of those with osteoporosis were

searched to obtain treatment history. Our clinic only

provides oral osteoporotic drugs (raloxifene, weekly

alendronate, monthly ibandronate and strontium

ranelate). The treatment plan, risks, and benefits

of each drug, specific prescription required of each

drug, and contra-indications are discussed with the

patient before deciding the drug therapy. Patients

are involved in decision making and must pay for

treatment.

Descriptive statistics for basic demographic

factors, risk factors for osteoporosis, T-score

distribution, and treatment adherence were

presented. Women were categorised into three

subgroups according to their T-score and based on

WHO recommendations3: normal BMD (T-score

≥-1.0 at either the hip or spine), osteopenia (T-score

between <-1.0 and -2.5), and osteoporosis (T-score

<-2.5). The Chi squared test was used to test

for a significant association between categorical

risk factors and osteoporosis. Stepwise binomial

logistic regression analysis using factors found to

have a significant correlation with BMD of T-score

of <-2.5 was performed to identify risk factors that

best predict osteoporosis. Analysis of variance was

used to analyse the difference between group means.

Level of significance was set at alpha = 0.05 for the

two-tailed tests. Data analyses were performed

using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(version 23.0; IBM, New York, US).

Results

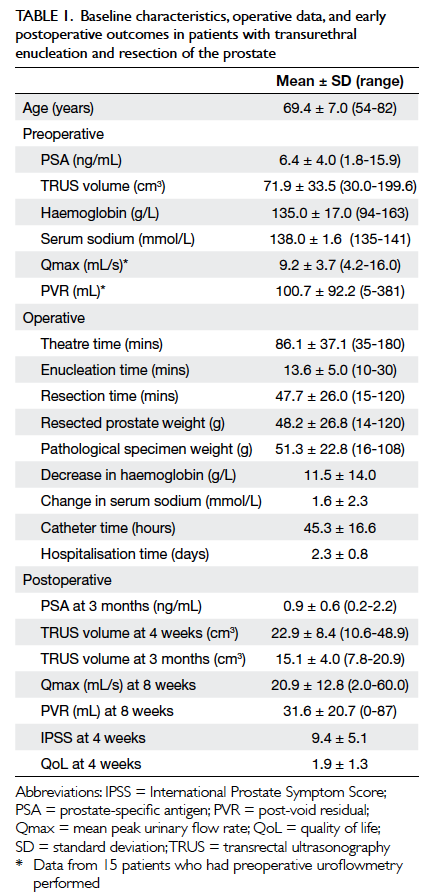

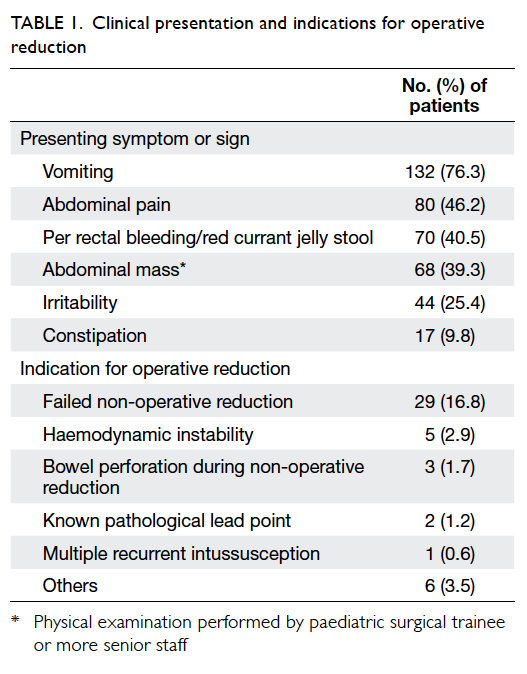

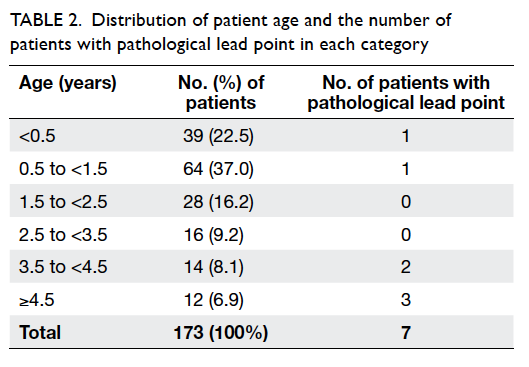

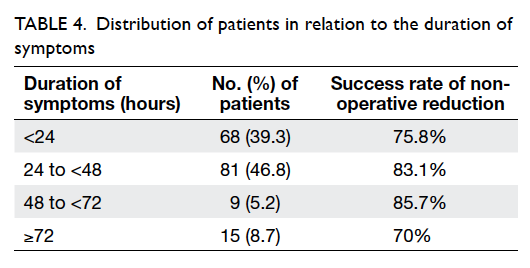

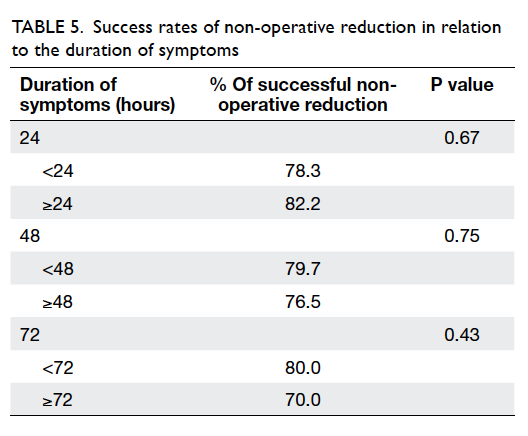

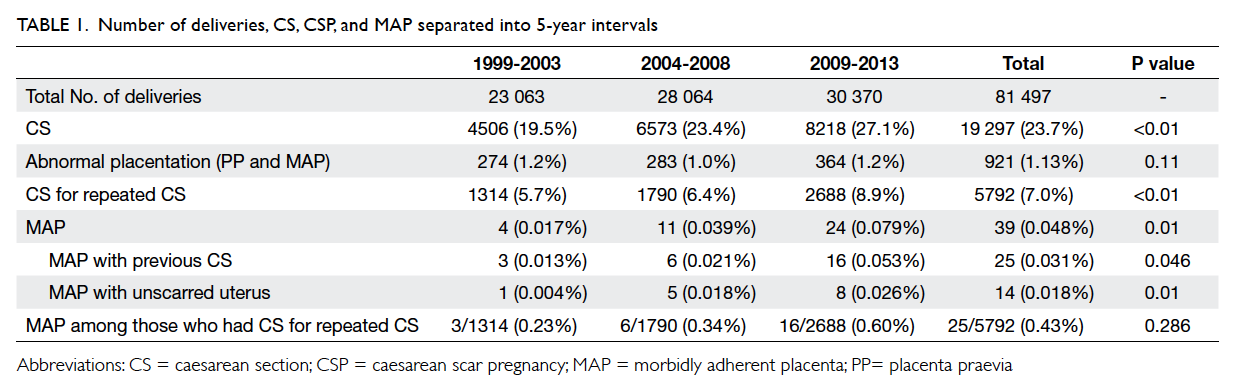

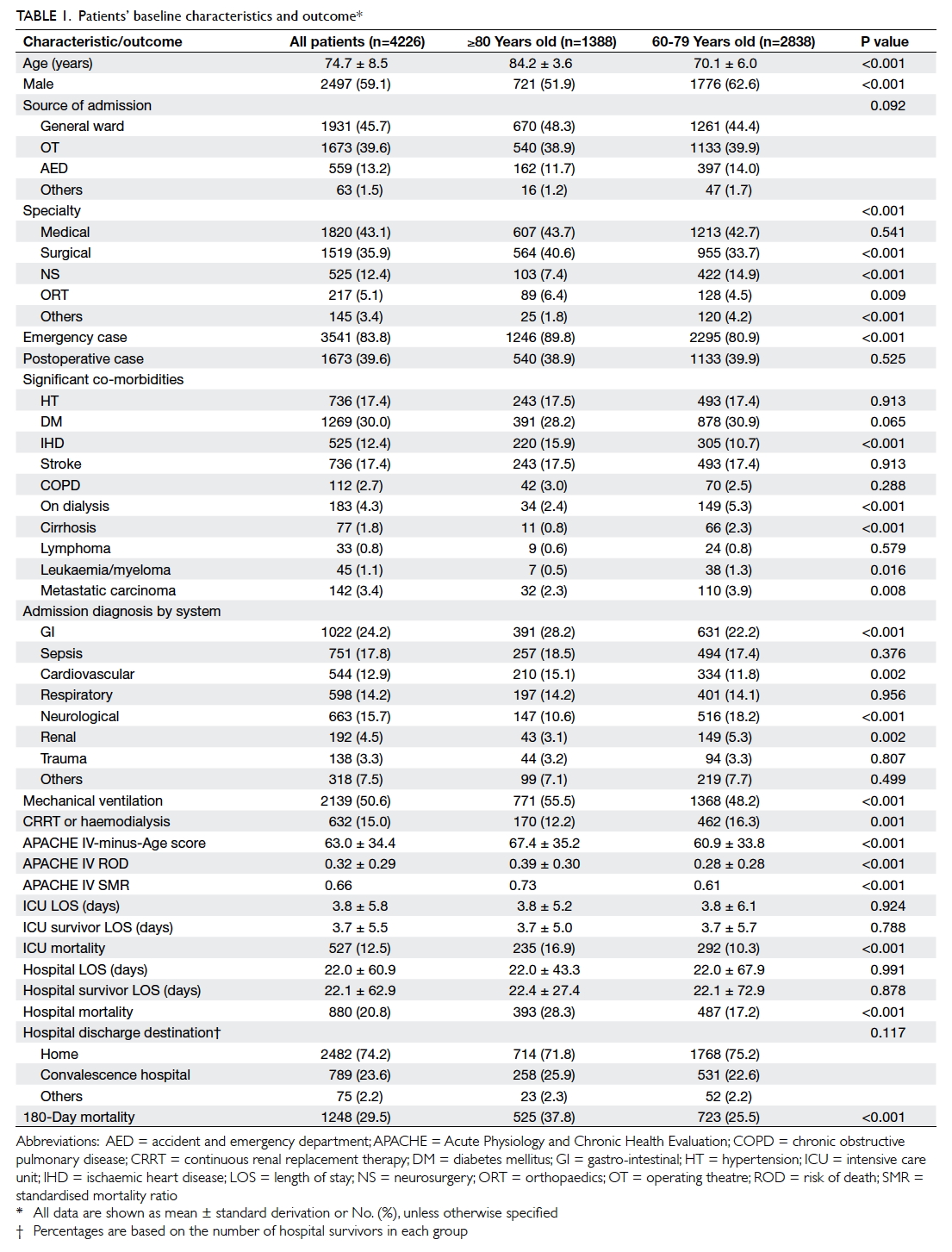

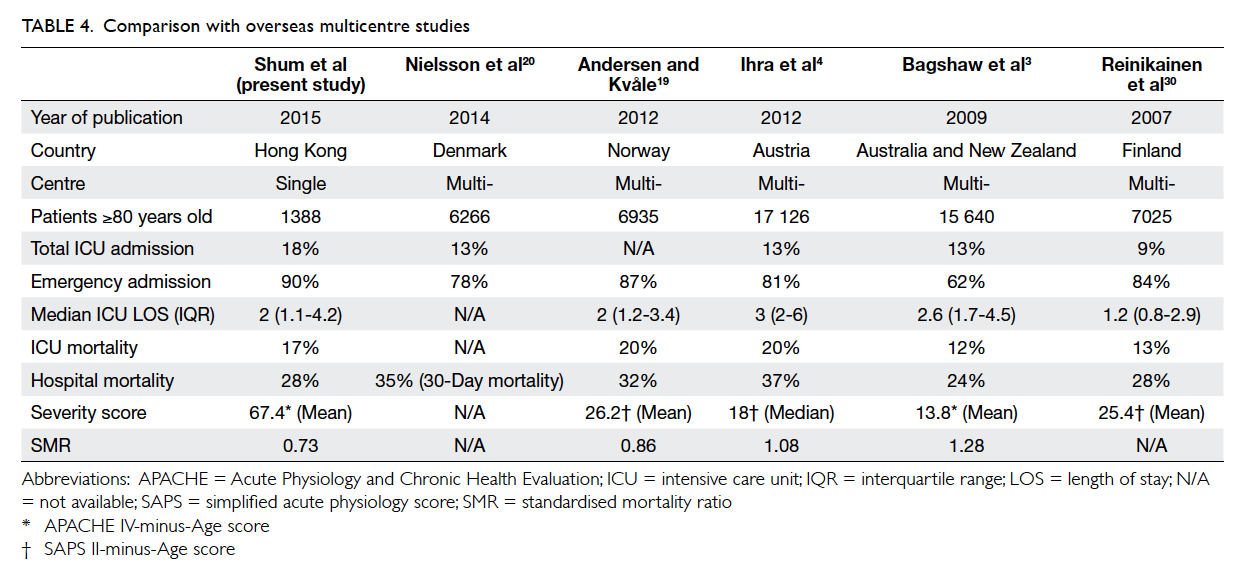

Between January 2008 and December 2011, 1507

DXA scans were performed for eligible women. Their

mean (± SD) age was 58.2 ± 6.4 years and the mean

age at menopause was 49.9 ± 4.0 years. The median

duration of menopause (years from menopause to

date of DXA) was 7 years (interquartile range, 3-11

years). The number of women with risk factors for

osteoporosis in the whole group and subgroups are

listed in Table 1. Only 1% of participants were unable

to recall whether or not there was a parental history

of osteoporosis or hip fracture.

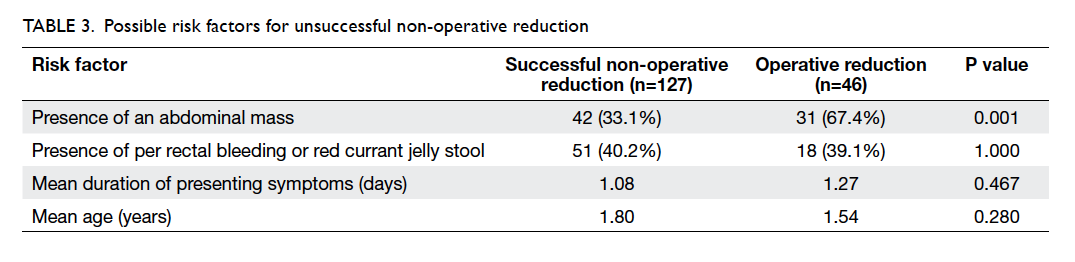

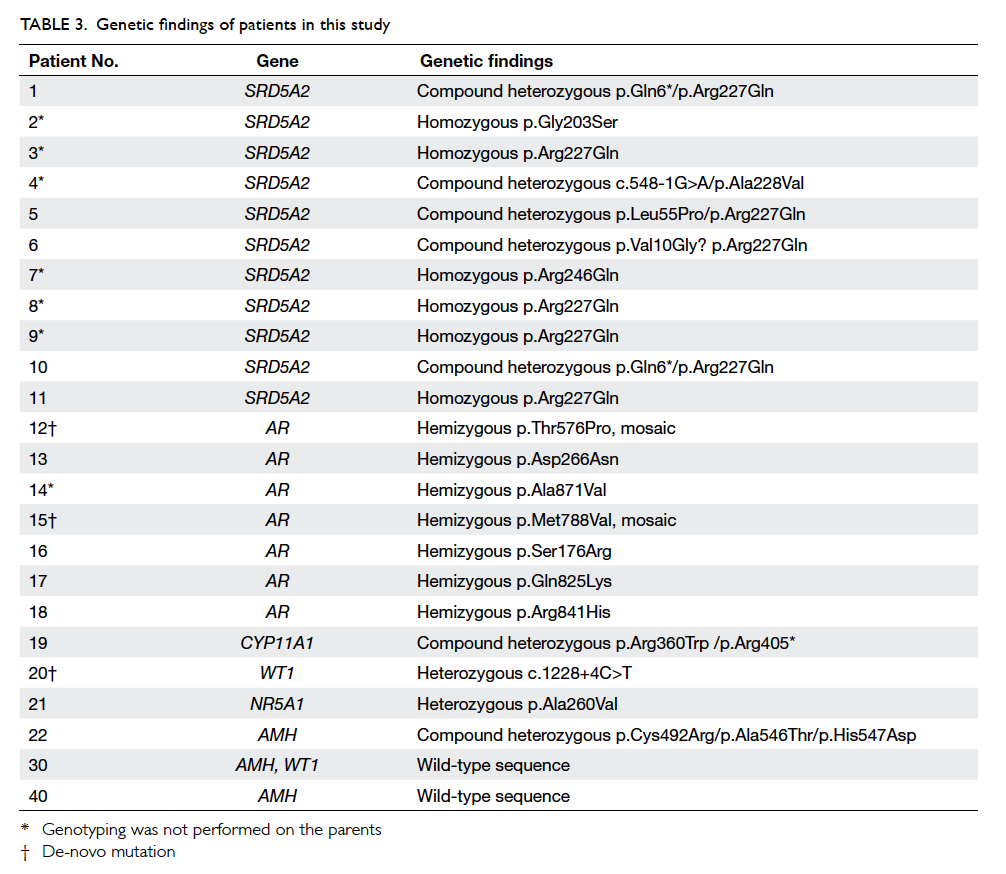

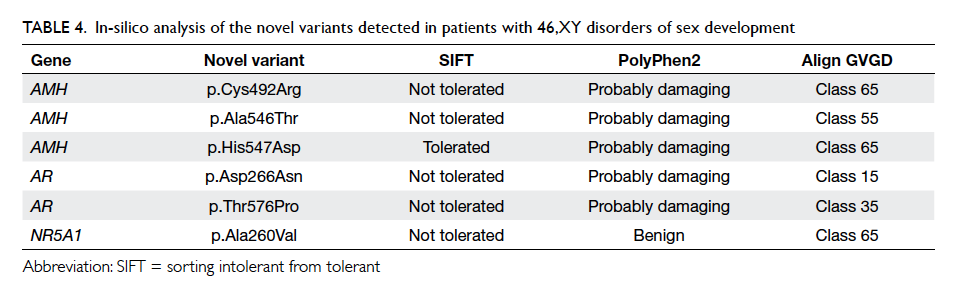

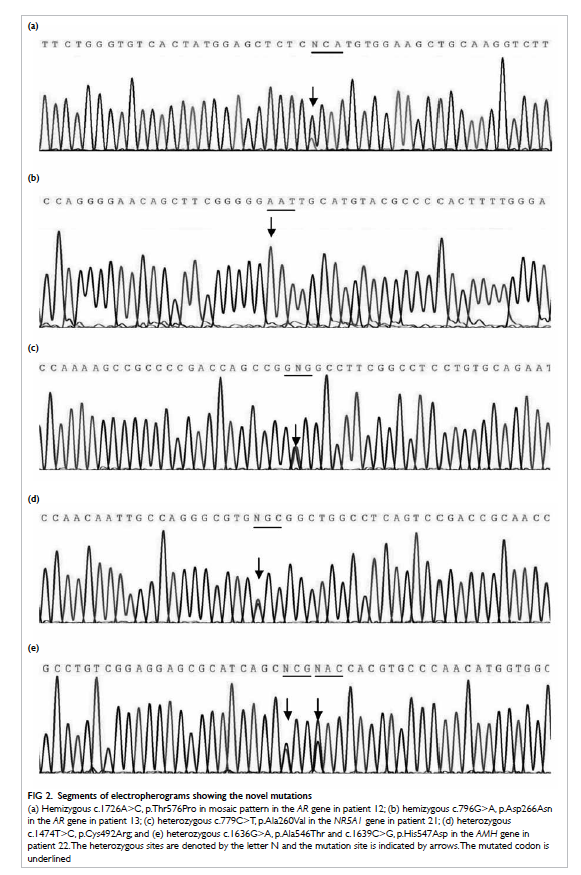

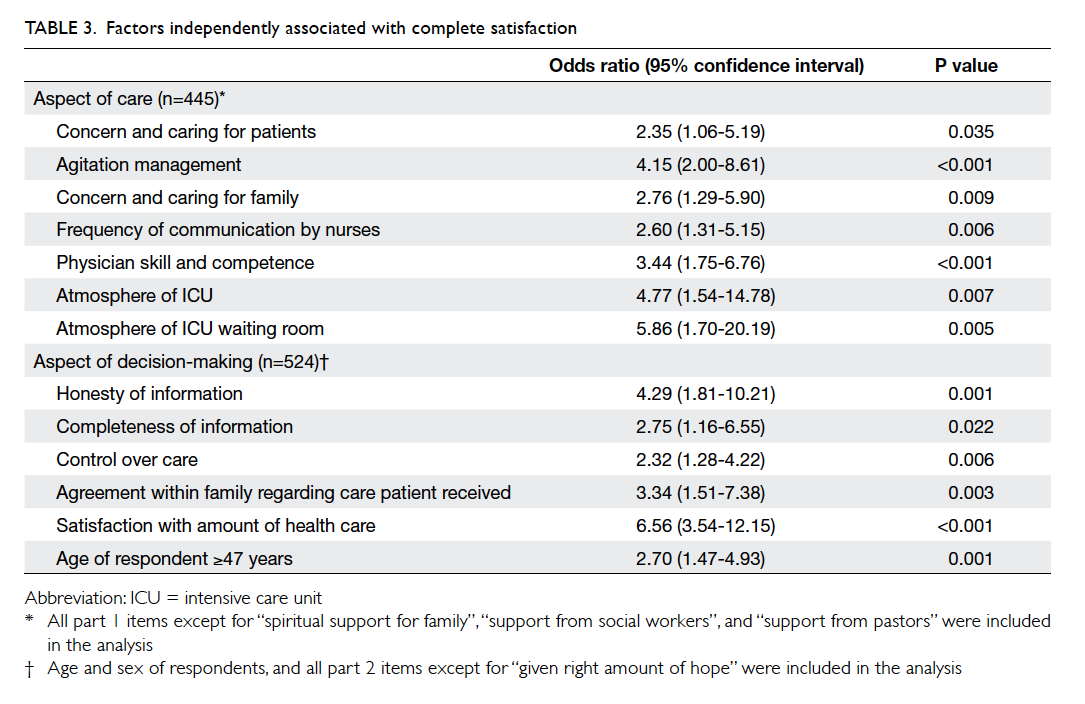

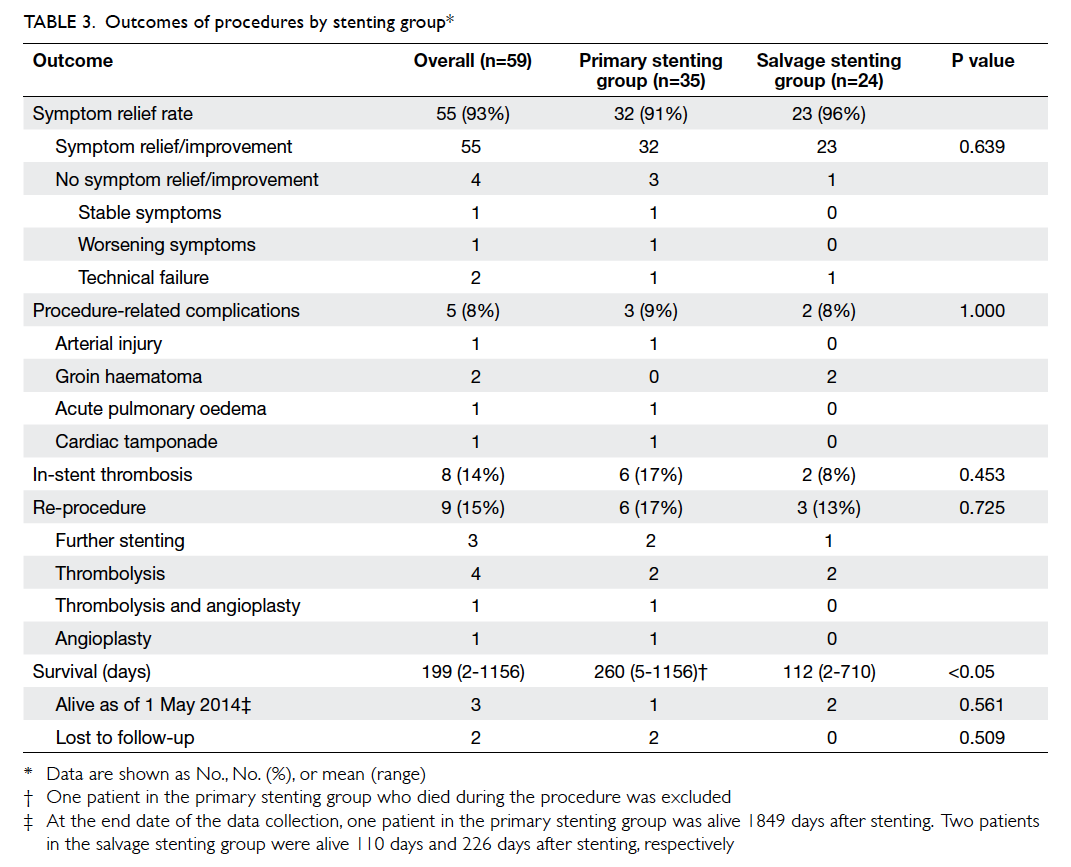

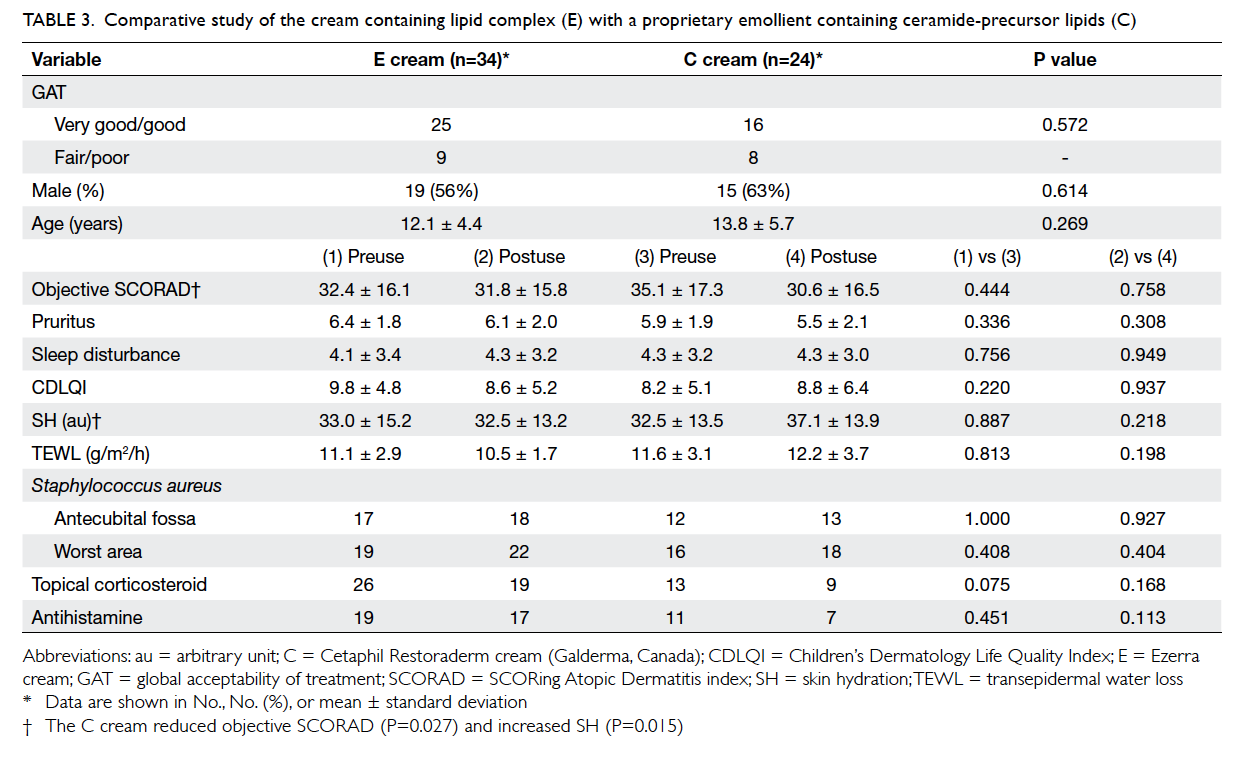

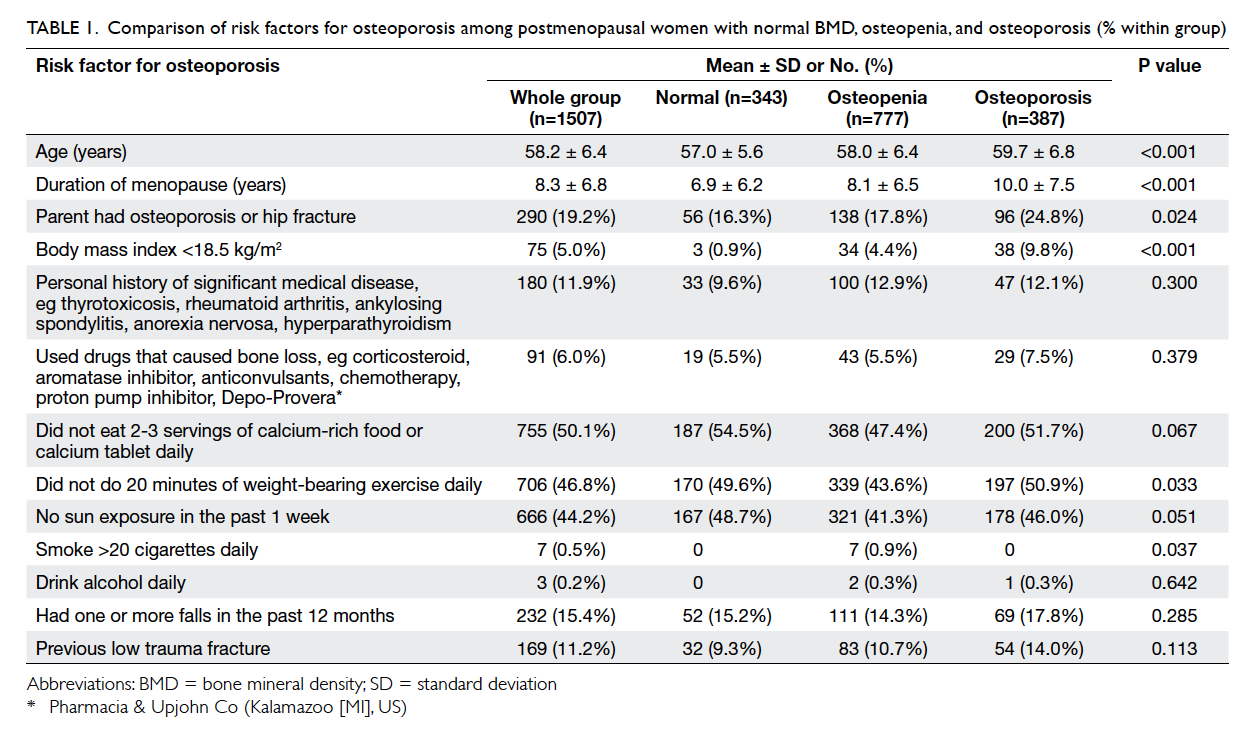

Osteoporosis was diagnosed in 25.7% of women

and osteopenia in 51.6%. The mean age of women

with normal BMD, osteopenia, and osteoporosis

was 57.0 ± 5.6 years, 58.0 ± 6.4 years, and 59.7 ±

6.8 years, respectively (P<0.001). The mean age at

menopause for each subgroup was the same: 50.0

years (P=0.441). Apart from age, BMI of <18.5 kg/m2

(P<0.001), duration of menopause (P<0.001),

parental history of osteoporosis or hip fracture

(P=0.024), and not doing 20 minutes of weight-bearing

exercise daily (P=0.033) were significant

risk factors for osteoporosis. Although smoking is a

significant risk factor for low bone mass, there were

too few smokers in this group to make any meaningful

comparison. The other risk factors did not show a

significant association with osteoporosis (Table 1).

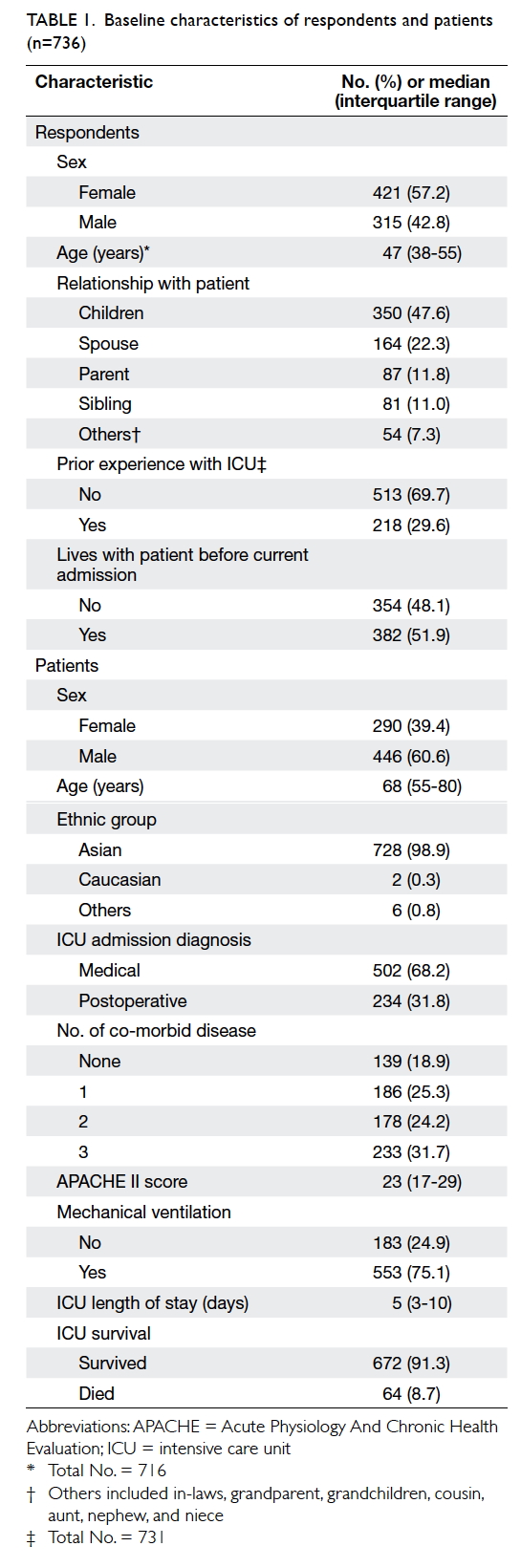

The proportion of women who had risk factors and

who had spine osteoporosis and hip osteoporosis is

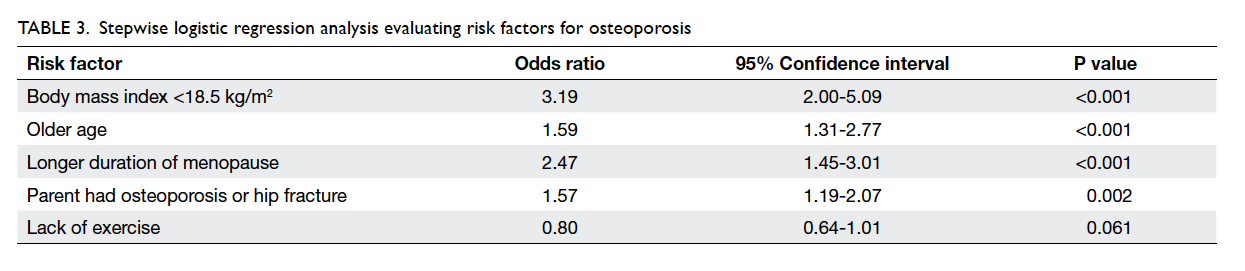

listed in Table 2. The results of the stepwise logistic

regression analysis are shown in Table 3—only older

age, low BMI, longer duration of menopause, and

parental history remained significant.

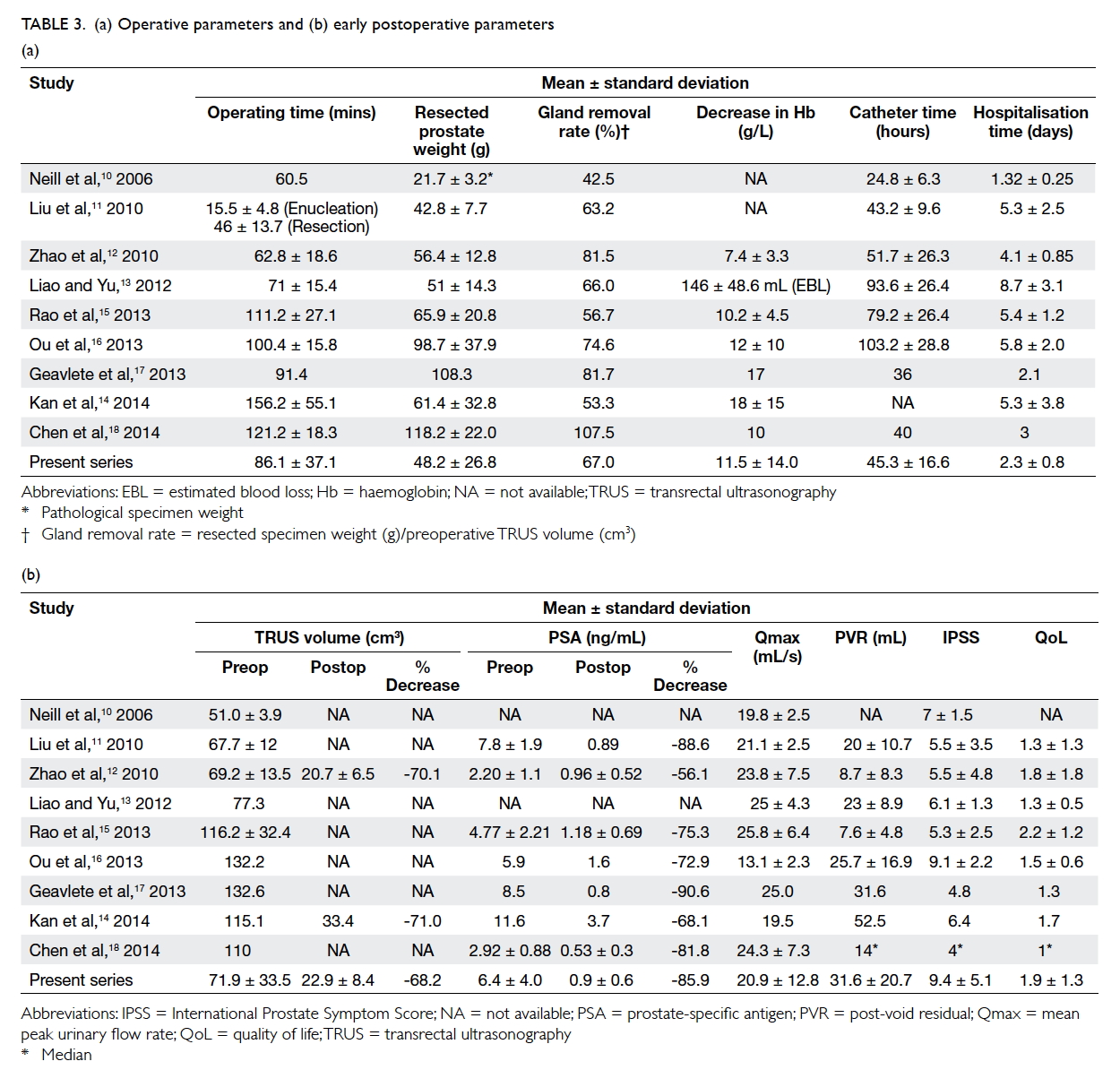

Table 1. Comparison of risk factors for osteoporosis among postmenopausal women with normal BMD, osteopenia, and osteoporosis (% within group)

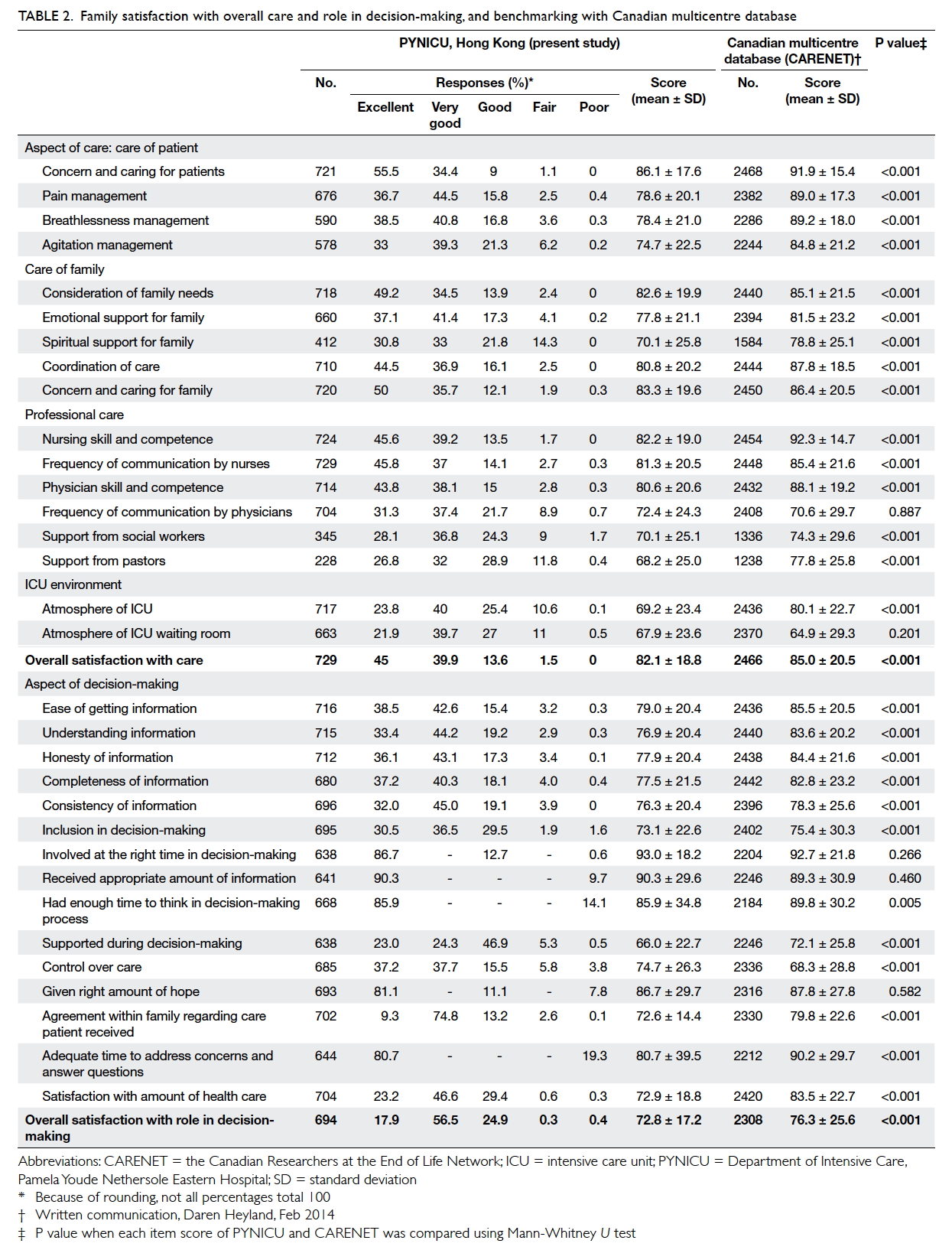

Among the 387 women with osteoporosis, 166

(42.9%) refused treatment because they feared of

the side-effects of drugs, 119 (30.7%) complied with

the treatment provided, 45 (11.6%) discontinued

treatment due to side-effects or worry about side-effects,

and 57 (14.7%) has defaulted from follow-up by

March 2015. The common side-effects that concerned

patients included hot flushes with raloxifene, gastric

and musculoskeletal pain with bisphosphonates, and

loose stools and diarrhoea with strontium ranelate.

For major adverse events, patients were concerned

about atypical fracture and osteonecrosis of the jaw

with bisphosphonates and increased cardiac risk

with strontium ranelate. Among the 119 women who

complied with treatment, 20 were still on treatment

in March 2015 and 99 were taking a drug holiday

after 2 to 6 years’ treatment that brought BMD to the

osteopenic range. Those who refused treatment were

significantly older with a mean age of 61.2 ± 7.8 years

(P<0.001).

Discussion

Osteoporosis is estimated to affect 200 million

women worldwide, which is approximately one

tenth of women aged 60 years, one fifth of those

aged 70 years, two fifths of those aged 80 years, and

two thirds of women aged 90 years.14 It has been

estimated that approximately 30% of postmenopausal

American women15 and 23% of postmenopausal

Australian women have osteoporosis.16 The

prevalence of osteoporosis in postmenopausal

Indonesian women has been reported to be 20.2%

in the lumbar vertebrae.17 In Germany, 23.3% of

postmenopausal German women aged 50 to 64 years

had osteoporosis.18 The prevalence of osteoporosis

(25.7%) in this study was similar to the prevalence rate

of 24.9% reported by another local epidemiological

study.19 Because of the silent nature of osteoporosis,

most patients who do not undergo DXA are unaware

of the diagnosis. Realisation usually comes when a

fragility fracture occurs.

Screening DXA is recommended for women

aged 65 years and over as well as for at-risk younger

women.20 21 In our subjects, age, low BMI, positive parental history of osteoporosis or hip fracture, and

duration of menopause were significant risk factors.

The Osteoporosis Self-assessment Tool for Asians is a

simple validated tool that can determine the need for

DXA, based on age and body weight.22 Osteoporosis

has been shown by many studies to have a strong

genetic influence.23 24 25 A parental history of fracture,

particularly of the hip, confers an increased risk of

fracture that is independent of BMD.26 Most of our

patients could remember their menopause age and

provide a parental history of osteoporosis or hip

fracture for assessment.

Apart from delineating the magnitude of

osteoporosis among postmenopausal women, this

study also showed that almost half of them did

not have an adequate calcium intake, and did not

perform sufficient weight-bearing exercise or have

enough sun exposure. The National Osteoporosis

Foundation (NOF) recommends 1200 mg calcium

and 800 to 1000 IU vitamin D daily for women

aged 50 and beyond.21 Nearly all Asian countries

fall far below this recommendation. The median

dietary calcium intake for the adult Asian

population is approximately 450 mg/day.9 The recent

calcium calculator launched by the International

Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) is a useful tool to

help women assess their daily calcium intake (http://www.iofbonehealth.org/calcium-calculator). Studies

carried out across different countries in South and

South-East Asia have shown, with few exceptions,

widespread prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and

insufficiency in both sexes and all age-groups of

the population.27 The IOF therefore recommends

800 IU/day vitamin D for everyone, even for those

with regular effective sun exposure.28 The NOF also

recommends regular weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening

exercise to improve agility, strength,

posture, and balance. This may reduce the risk of

falls and fractures.9 There is clear evidence that tai

chi is effective for fall prevention and improving

psychological health and is associated with general

health benefits for older people.29 Meta-analysis

of the effect of tai chi on osteoporosis or BMD is,

however, inconclusive as a result of many different

tai chi exercises being studied, and variable design

and different quality-rating instruments used in the

systematic reviews of tai chi literature.30 We were

unable to show a significant association of diet,

exercise, and sun exposure with osteoporosis in this

cohort, probably due to limitations in capturing

accurate information as discussed below. The

important message to emphasise is that, in this group

of self-selected clinic attendees who are in general

believed to be more health conscious, the proportion

of women adopting such healthy lifestyle strategies

was not high. The situation in the general population

might be worse. Since these are important lifestyle

strategies for osteoporosis prevention, clinicians

should encourage all postmenopausal women to

adopt them.

It is of concern that in this study almost 43%

of women with osteoporosis refused treatment.

Among those who agreed to start treatment, only

half adhered to treatment. Some women decided

to stop treatment prematurely because they were

distressed by reports of major adverse events

such as atypical fracture and osteonecrosis of the

jaw. Some women read news articles that stated

treatment should not exceed 2, 3, or 5 years, then

refused to continue treatment beyond this time

frame. Although bisphosphonates are long-acting

drugs, extended dosing does not compensate for

poor drug compliance. A recent study showed that

64.0% of patients discontinued weekly alendronate,

66.4% discontinued weekly risedronate, and 68.2%

discontinued monthly ibandronate.31 Hence dosing

regimens are unlikely to be solely responsible

for poor compliance. Other factors that reduced

drug compliance included: cost of medication,

low motivation to take drug as patients were

asymptomatic, patients did not believe they were

at significant risk of fracture, some patients had

difficulty complying with the prescribed regimen

for bisphosphonates and strontium ranelate in the

context of their daily routine, the patient was already

on a number of medications for other illnesses

and refused more. Further research is needed to

understand patient decision-making models for

osteoporosis treatment and how health education

from various sources (health-care providers, family,

friends, and media) can modify their attitude

towards osteoporosis treatment.

The main limitations of this study are, first,

selection bias because some women refused to

have DXA. The study women were therefore self-selected,

hence the prevalence reported might not

be representative of the population. Second, the

information in the checklist was provided by patient

recall and their responses were not verified. Similarly,

the menopause age was provided by the patient and

could not be verified. Third, the monitoring period

was insufficient to provide fracture data that would

allow comparison of outcome in patients who

adhered to treatment and those who did not. Fourth,

drug compliance (whether the drug was taken

correctly), drug omission, stockpiling or transfer of

medicines between friends and relatives were not

assessed in detail.

Conclusions

Osteoporosis is prevalent in the local population,

affecting one in four postmenopausal women. Those

with risk factors such as low BMI, older age, longer

duration since menopause, and parental history of

osteoporosis or hip fracture, should undergo DXA.

In addition to prompt diagnosis and treatment of

osteoporosis, physicians should monitor patient

drug compliance at each follow-up. At the same

time, calcium intake, sun exposure, and exercise

pattern should also be evaluated to help optimise

their bone health.

References

1. Recker RR, Lappe J, Davies K, Heaney R. Characterization

of perimenopausal bone loss: a prospective study. J Bone

Miner Res 2000;15:1965-73. Crossref

2. Pouillès JM, Trémollières F, Ribot C. Vertebral bone loss in

perimenopause. Results of a 7-year longitudinal study [in

French]. Presse Med 1996;25:277-80.

3. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening

for postmenopausal osteoporosis. WHO Technical Report

Series 843. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994.

4. Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H. Meta-analysis of how well

measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of

osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 1996;312:1254-9. Crossref

5. Kung AW, Lee KK, Ho AY, Tang G, Luk KD. Ten-year risk of

osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal Chinese women

according to clinical risk factors and BMD T-scores: a

prospective study. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:1080-7. Crossref

6. Lau EM, Cooper C. The epidemiology of osteoporosis. The

oriental perspective in a world context. Clin Orthop Relat

Res 1996;323:65-74. Crossref

7. Lau EM, Cooper C, Fung H, Lam D, Tsang KK. Hip fracture

in Hong Kong over the last decade—a comparison with the

UK. J Public Health Med 1999;21:249-50. Crossref

8. Kung AW, Yates S, Wong V. Changing epidemiology

of osteoporotic hip fracture rates in Hong Kong. Arch

Osteoporos 2007;2:53-8. Crossref

9. The Asian Audit. Epidemiology, costs and burden of

osteoporosis in Asia 2009. International Osteoporosis

Foundation; 2009. Available from: http://www.iofbonehealth.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/Audit%20Asia/Asian_regional_audit_2009.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2015.

10. Lau EM, Chan HH, Woo J, et al. Normal ranges for vertebral

height ratios and prevalence of vertebral fracture in Hong

Kong Chinese: a comparison with American Caucasians. J

Bone Miner Res 1996;11:1364-8. Crossref

11. Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA. Risk of

subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and

women. JAMA 2007;297:387-94. Crossref

12. International Osteoporosis Foundation. The Breaking

Spine. 2010. Available from: http://share.iofbonehealth.org/WOD/2010/thematic_report/2010_the_breaking_spine_en.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2015.

13. Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM. A

systematic review of persistence and compliance with

bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int

2007;18:1023-31. Crossref

14. Kanis JA. Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health

care level. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Technical

Report. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre

for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, UK;

2007. Available from: http://www.iofbonehealth.org/sites/default/files/WHO_Technical_Report-2007.pdf. Accessed

22 May 2015.

15. Melton LJ 3rd, Chrischilles EA, Cooper C, Lane AW, Riggs

BL. Perspective: How many women have osteoporosis? J

Bone Miner Res 1992;7:1005-10. Crossref

16. Estimating the prevalence of osteoporosis in Australia. Cat.

no. PHE 178. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare (AIHW); 2014. Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129548481.

Accessed 22 May 2015.

17. Meiyanti. Epidemiology of osteoporosis in postmenopausal

women aged 47 to 60 years. Univ Med 2010;29:169-76.

Available from: http://www.univmed.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Meiyanti.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2015.

18. Häussler B, Gothe H, Göl D, Glaeske G, Pientka L,

Felsenberg D. Epidemiology, treatment and costs

of osteoporosis in Germany—the BoneEVA Study.

Osteoporos Int 2006;18:77-84. Crossref

19. Lau EM, Chung HL, Ha PC, Tam H, Lam D. Bone mineral

density, anthropometric indices, and the prevalence of

osteoporosis in Northern (Beijing) Chinese and Southern

(Hong Kong) Chinese women—the largest comparative study

to date. J Clin Densitom 2015 Jan 13. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

20. 2013 Official Positions of the International Society for

Clinical Densitometry. Available from: http://www.iscd.org/documents/2014/02/2013-iscd-official-position-brochure.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2015.

21. National Osteoporosis Foundation. The clinician’s guide to

prevention and treatment of osteoporosis 2014. Available

from: http://nof.org/files/nof/public/content/file/2791/upload/919.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2015.

22. Koh LK, Sedrine WB, Torralba TP, et al. A simple tool to

identify Asian women at increased risk of osteoporosis.

Osteoporos Int 2001;12:699-705. Crossref

23. Pocock NA, Eisman JA, Hopper JL, Yeates MG, Sambrook

PN, Eberl S. Genetic determinants of bone mass in adults.

A twin study. J Clin Invest 1987;80:706-10. Crossref

24. Seeman E, Hopper JL, Bach LA, et al. Reduced bone mass

in daughters of women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med

1989;320:554-8. Crossref

25. Thijssen JH. Gene polymorphisms involved in the regulation

of bone quality. Gynecol Endocrinol 2006;22:131-9. Crossref

26. Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. A family history

of fracture and fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Bone

2004;35:1029-37. Crossref

27. Mithal A, Wahl DA, Bonjour JP, et al. Global vitamin D

status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos

Int 2009;20:1807-20. Crossref

28. Dawson-Hughes B, Mithal A, Bonjour JP, et al. IOF position

statement: vitamin D recommendations for older adults.

Osteoporos Int 2010;21:1151-4. Crossref

29. Lee MS, Ernst E. Systematic reviews of t’ai chi: an overview.

Br J Sports Med 2012;10:713-8. Crossref

30. Alperson SY, Berger VW. Opposing systematic reviews:

the effects of two quality rating instruments on

evidence regarding t’ai chi and bone mineral density in

postmenopausal women. J Altern Complement Med

2011;17:389-95. Crossref

31. Fan T, Zhang Q, Sen SS. Persistence with weekly and

monthly bisphosphonates among postmenopausal women:

analysis of a US pharmacy claims administrative database.

Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2013;5:589-95. Crossref