Hong Kong Med J 2015 Aug;21(4):304–9 | Epub 9 Apr 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144350

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Pain management programme for Chinese patients: a 10-year outcome review

MC Chu, FFPMANZCA1;

Rainbow KY Law, MPhil2;

Leo CT Cheung, MSc3;

Marlene L Ma, MNurs4;

Ewert YW Tse, MSc5;

Tony CM Wong, PhD6;

PP Chen, FFPMANZCA7

1 Department of Anaesthesia, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

2 Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong

3 Department of Physiotherapy, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Tai Po, Hong Kong

4 Pain Management Centre, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Tai Po, Hong Kong

5 Department of Occupational Therapy, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Tai Po, Hong Kong

6 Department of Clinical Psychology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

7 Department of Anaesthesiology and Operating Services, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Tai Po, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr MC Chu (chu0079@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To review the clinical and social benefits

of a pain management programme in Hong Kong.

Design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary out-patient clinic, Hong Kong.

Participants: Patients with chronic non-cancer pain and prolonged (mean, 46 months) psychosocial disability who joined the Comprehensive Outpatient Pain Engagement programme between 2002 and 2012.

Intervention: A structured 6-week out-patient pain rehabilitation course designed to improve function and reduce disability, regardless of the cause or severity of pain.

Main outcome measures: Social outcomes included return-to-work rate, hospital admissions, and out-patient visits. Physical outcomes included tolerance to sitting and standing. Psychological constructs such as mood, catastrophisation, self-efficacy, quality of life, and perceived performances were used. Each measure was taken before and 1 year after the programme.

Results: There was significant increase in return-to-work rate 1 year after commencement of the programme (35% after vs 17% before the programme; odds

ratio=3.01), reduction in medical utilisation, and improvement in all physical and psychological

measures. Pain intensity, psychological distress, and history of work-related injuries were not related to

the likelihood of return to work. Shorter duration of pain and higher physical functioning score in

36-Item Short-Form Health Survey were prognostic indicators.

Conclusions: Patients with chronic pain who joined the Comprehensive Outpatient Pain Engagement programme showed significant functional

improvement despite the long history of pain.

New knowledge added by this

study

- A programme of pain management based on cognitive behavioural principles is an effective treatment with potentially significant social savings for sufferers of chronic non-cancer pain in Hong Kong.

- The pain programme is an effective treatment, and shall be a significant part of chronic pain rehabilitative services in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Chronic pain is a common condition that affects

about 10% of the population in Hong Kong.1 Patients

with chronic pain suffer a variety of physical and

psychological co-morbidities, become medically

dependent, and have significant loss of quality of life

and work capacity.2

Pain management programmes based

on cognitive behavioural principles have been

recognised as an effective treatment for various

chronic pain conditions.3 Such programmes are

structured to incorporate a variety of rehabilitative

strategies, with clearly defined physical,

psychological, and social outcomes. Such concepts

and practices are, however, largely unknown to the

Chinese community.

In 2002, the Comprehensive Outpatient Pain

Engagement (COPE) programme was established

at the Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital,

Hong Kong, with reference to the model of the

Active Day Patient (ADAPT) programme at the

University of Sydney, Australia.4 This is a 14-day out-patient

rehabilitation programme with 100 hours

of clinical time per course. Core topics included

education about pain pathophysiology, behavioural

training with graded activities and exercises, pacing,

relaxation, strengthening and stretching exercises,

thought management, communication, as well as

activity planning and appropriate use of medication.

Individuals from multiple disciplines participated in

the programme, including pain specialists, clinical

psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational

therapists, pain nurses, medical social workers,

and hospital chaplains. To ensure consistency,

all staff members were trained at the same Pain

Management and Research Centre at the University

of Sydney, and all courses were conducted according

to a standardised timetable and protocol5 in use

since its inception. From 2002 to 2012, 20 courses

were conducted, with one to three courses per year,

and eight to 12 participants per course.

An interim review in 20075 demonstrated

improved physical, psychological, and social

functioning among participants up to 1 year after

the programme. The major limitation of that report

was the small number of subjects (n=49). This

report is an extended outcome study of the pain

management programme. With more subjects,

statistical significance should be improved.

Methods

All participants were recruited from the Pain

Management Centre at the Alice Ho Miu Ling

Nethersole Hospital, a tertiary referral centre in

Hong Kong. They were patients with chronic non-cancer

pain, irrespective of site and diagnosis.5

They were assessed by the clinical psychologist,

pain nurse, and pain specialist for eligibility to join

the programme as a possible pain management

option. Those with untreated psychiatric conditions,

significant suicidal or homicidal risk, illiterate (either

written or spoken Cantonese), and non-acceptance

to the therapy were not included in the study

or the programme. Once recruited, prospective

participants gave written informed consent for data

collection and research, and agreement that medical

treatment for pain control would remain unchanged

until the programme commenced. On completion of

the programme, routine follow-ups were arranged

for up to 1 year.

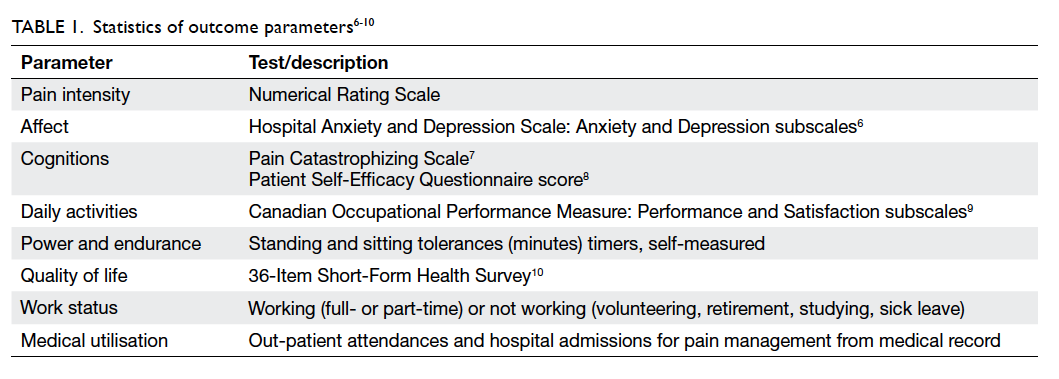

A standardised set of measurements (Table

16 7 8 9 10) was used to assess the physical, psychological, and social functioning on the first day of the

programme, and 12 months after each course. These

measurements were self-reporting, self-administered

questionnaires commonly used among pain clinics

in Hong Kong and staff were familiar with the

measurement tools. All measurements were made

in Chinese and were validated in the local setting.

Medical records of every participant were reviewed

1 year before and after the programme for history of

injury, work status, pain-related admissions, or out-patient

consultations.

Demographic and pain information were

presented as descriptive statistics. Paired t test,

Wilcoxon signed rank test, and contingency table

with Fisher’s exact test were used to evaluate the

overall effectiveness of the programme. Logistic

regression predicting 12-month return-to-work

status was performed with a history of injury at

work, age, duration of pain, and the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF36) physical functioning as

covariates using the ‘enter’ regression method. The

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 10.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US) was used

for the calculations. A level of significance of P or

Z<0.05 was accepted for the study.

This study was approved by the local ethics

committee (Joint CUHK-NTEC Clinical Research

Ethics Committee CREC2013.205).

Results

From 2002 to 2012, up to 4000 new cases of chronic

pain were assessed at the clinic, and 158 patients

were recruited. The exact number of patients for

each of the exclusion criterion was unknown. Over

the years, 14 participants withdrew during the

course, and two defaulted from post-programme

reviews. A total of 142 participants completed the

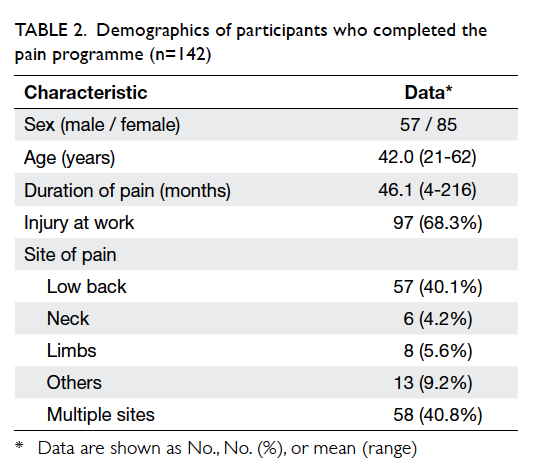

course (Table 2).

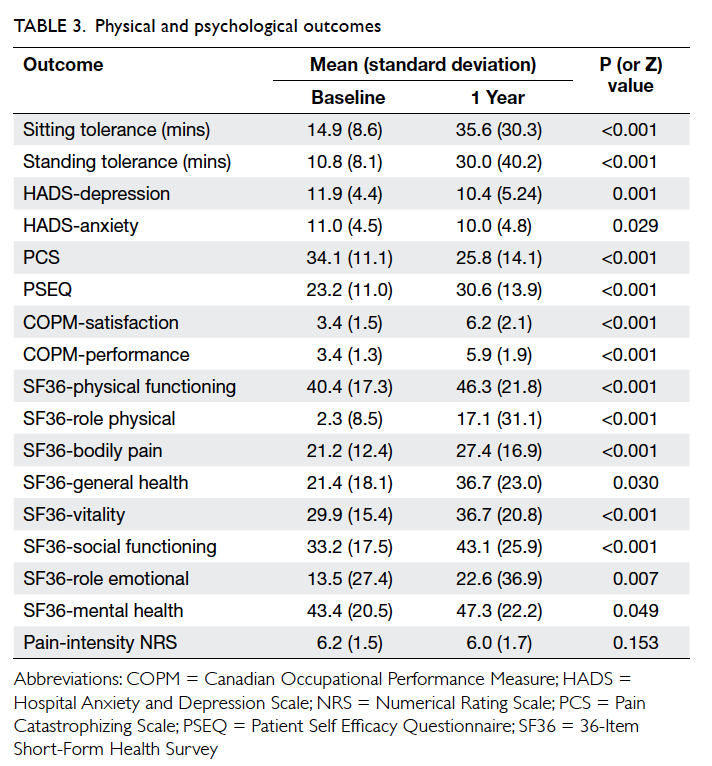

There was a significant improvement in all of

the physical and psychological parameters 1 year

after the programme despite a long history (mean,

46 months) of signs and symptoms before the

programme (Table 3). Despite similar pain-intensity

ratings, functional tolerance (such as sitting and

standing) had more than doubled. Depression,

anxiety, and catastrophisation (psychological

tendency to ruminate and magnify negative aspects

of pain and health) scores were reduced. Self-efficacy,

perceived performance and satisfaction with daily

activities, and quality-of-life scores had improved.

All changes were statistically significant (P<0.05).

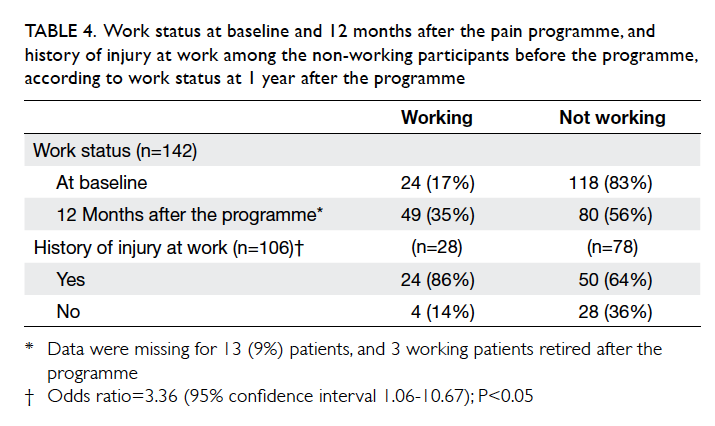

There was also a considerable improvement

in work status (Table 4). Of the 142 participants,

only 24 (17%) were working before the programme.

The work statuses of 129 participants were known

after the programme, of whom 49 (35%) were in

work (including 28 who were not working before

the programme). The odds ratio (OR) of participants

working after the programme versus before was

3.01 (95% confidence interval, 1.71-5.30; P=0.0002).

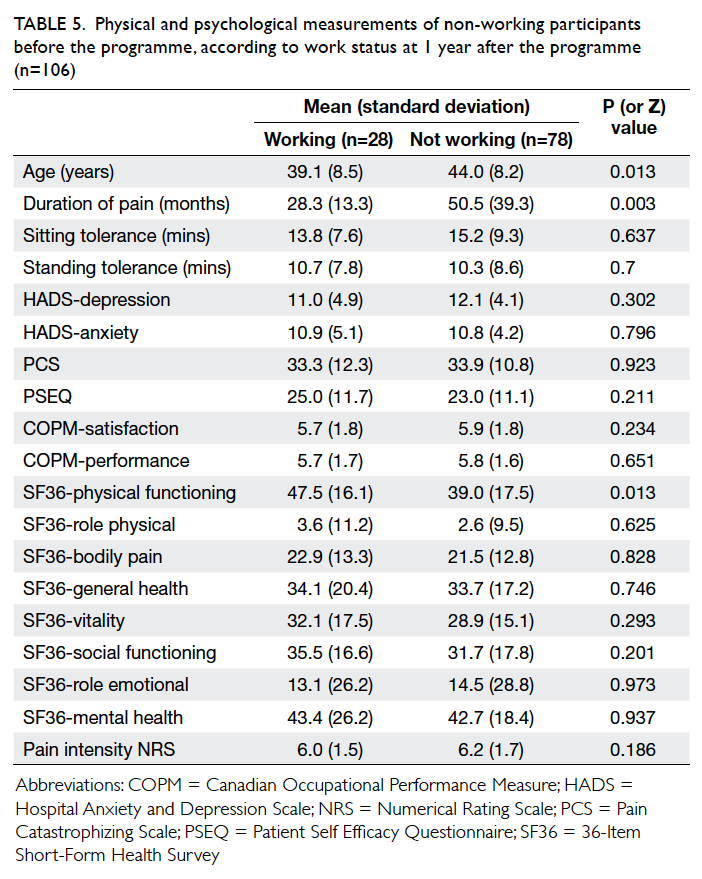

Further analysis of the 106 patients who were

not working initially revealed that baseline pain

intensity was similar among those who returned to

work and those who did not (Table 5). There were

also no statistically significant differences in the

psychological and physical parameters except a

higher SF36 physical functioning score (47.5 vs 39.0).

Other significant differences included younger age

(39.1 vs 44.0 years) and shorter duration of pain (28.3

vs 50.5 months) among those who returned to work.

History of injury at work was also more common in

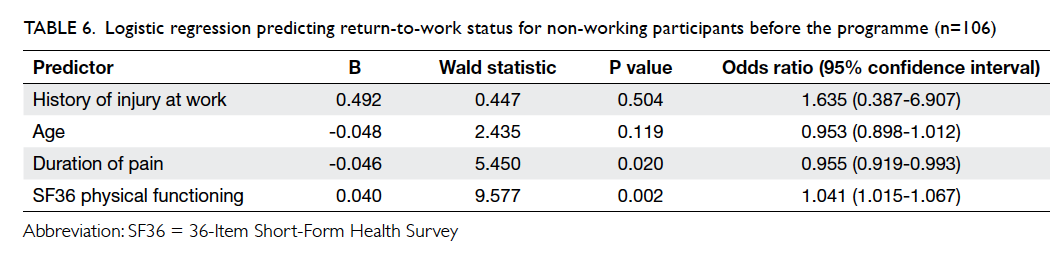

this group (OR=3.36, Table 4). Logistic regression on

these four significant variables predicting 12-month

return-to-work status showed that duration of pain

(OR=0.955, P=0.020) and SF36 physical functioning

(OR=1.041, P=0.002) were significant independent

predictors, while history of injury at work and age

were not (Table 6).

Table 4. Work status at baseline and 12 months after the pain programme, and history of injury at work among the non-working participants before the programme, according to work status at 1 year after the programme

Table 5. Physical and psychological measurements of non-working participants before the programme, according to work status at 1 year after the programme (n=106)

Table 6. Logistic regression predicting return-to-work status for non-working participants before the programme (n=106)

Utilisation of medical resources was also

significantly reduced after the programme: average

out-patient attendance (visits per person per year)

reduced from 7.95 to 6.39, and hospitalisation

(admissions per person per year) reduced from 0.59

to 0.21. All changes were statistically significant

(P<0.05).

Discussion

The COPE programme is one of the first pain

programmes for psychosocial rehabilitation of

patients with chronic non-cancer pain in a Chinese

community. As the concepts of self-management,

active coping, and functional improvement

despite pain were new to the local patients and

staff, it took a considerable effort to train staff and

encourage local patients to join the programme.

The slow recruitment prevented the authors from

performing any randomised trial, and the sample

size was statistically unrepresentative of the

local chronic pain caseload (up to 400 new cases

per year, recruitment rate of approximately 4%).

Some important information, such as reasons for

exclusion from the programme, were not included in

the database. Selection bias might further limit the

usefulness of the information.

Despite the limitations, the results

demonstrated an all-round positive outcome for

patients who completed the programme. The

programme was not designed for pain reduction

and indeed the pain intensity never changed, yet

the participants became less fearful about pain and

movement, and were able to continue to function

despite the pain. The skills learnt in the programme

were simple, self-managing, did not require special

equipment or medications, and participants were

encouraged to solve problem and adopt these skills

in their own social setting. As the participants

managed to see the dissociation between pain and

disability, they become motivated to apply these

skills continuously. This may have contributed to the

lasting improvement.

The social improvement was very encouraging.

Not only was there a lasting reduction in utilisation

of medical resources, it came as a pleasant surprise

that about one quarter of non-working participants

were able to resume work. This is remarkable as this

was a cohort with very long duration of pain, with

most of the participants out of work for more than

2 years. It would also have been an unfavourable

course of prolonged work absenteeism for patients

with musculoskeletal pain and work-related

injuries.11 12 13 Our post-hoc analysis reconfirmed that it remained a significant prognostic indicator of

vocational outcome even after years of disability. As

work was such an important outcome for the patient

and the society, it would be useful to examine if early

intervention could generate better return-to-work

outcomes.

Another interesting finding was that most of

the biological and psychological parameters were

not associated with vocational outcome after the

programme. In other words, while the psychological

‘yellow flags’ might be useful in chronic pain and

disability prognosis,14 they might not be predictive of

vocational outcome among this cohort of subjects.

Apart from the long duration, our cohort of patients

was characterised by very low quality-of-life scores

in multiple domains. The poor psychological

profile might have rendered most psychological

measurements less discriminative than reported

elsewhere.15 The only significant psychological

prognostic indicator was a higher SF36 physical

functioning score. This domain was known to

have the strongest association with return-to-work

among all the SF36 domains for subjects with

chronic back pain,15 and stood out among other less

discriminative domains for predicting outcome.

Other prognostic factors, such as the patients’

expectation, social background, occupational ‘blue

flags’ and the contextual ‘black flags’, might be in

place and need further exploration.16 17 18 The economy

might have also contributed to the favourable

vocational outcome. However, the annual drop

in unemployment (approximately 1%) during the

period19 was much lower than the observed increase

in work rate at 1 year (18%), and was probably a

minor contribution to the overall improvement.

The relationship between compensable injuries and

return to work is much debated. Our data suggested

that history of injury at work might have been an

associating rather than independent variable in

vocational outcome, with other confounding factors

such as age or SF36. During each programme, the

long-term goal setting would include a discussion

on the impact of litigation and compensation on

returning to work and may have reduced their

potential detrimental effects.

Our findings provide a comparison with

those from other non-cancer pain rehabilitation

programmes in Hong Kong. In 2010, Luk et al20

published their rehabilitation programme outcome

for patients with chronic low back pain. Following

almost 400 hours of physiotherapy and occupational

therapy, physical function improved although mood

remained unchanged at 6 months.20 Approximately

52% of the participants returned to work 6 months

after the programme.20 Those who returned to work

showed a reduction in perceived disability, pain

intensity, better physical performance, and similar

mood compared with those who did not.20 The

apparent discrepancy between Luk et al’s study20 and

our study was due to differences in patient cohort and

programme design. In Luk et al’s study,20 the average

pain history was 22 months. These parameters

compared favourably with our cohort of mean pain

history of 46 months. Patients were referred from

different sources (orthopaedics and pain clinics)

with a different demographic (predominantly male

in Luk et al’s group20 vs predominantly female in ours)

and disease profile (exclusively back patients in Luk

et al’s group20 vs heterogeneous in ours). The duration

of therapy was almost 4 times longer in Luk’s study,20

allowing ample time for work strengthening and

vocational training. On the contrary, our programme

was designed for general rehabilitation and offered no

vocational training. The comparison demonstrated

the wide variety of presentation of pain patients, and

the spectrum of therapies available in Hong Kong

with different objectives and emphasis. Nonetheless

both studies were in agreement that duration of

absence from work was unanimously identified as a

prognostic indicator for return to work.

In 2012, Tse et al21 published their outcome

report of a pain management programme for chronic

non-cancer pain among elderly home residents.

Over 290 elderly subjects enrolled in the 8-week

programme with physical exercises and multisensory

art and craft therapy, together with pain education

for their carer. The pain intensity in some areas (back

and multiple joints) was significantly reduced after

the programme, together with increased range of

motion in all joints, and improvement in selected

mood measurements. Perceived quality of life, as

measured by SF12, did not differ significantly after

the programme. There were no data on physical

function, pain cognition, and social consequences.

As the patient group and the programme design and

outcome measurements were radically different to

our study and that of Luk et al,20 results could not be

compared nor conclusions drawn.

The practice of a multidisciplinary pain

programme has also begun recently in Asia. In 2012,

Cardosa et al22 reported a series of 120 patients who

underwent the MENANG programme in Malaysia, a

programme based on the same model (the ADAPT

programme) as ours. Despite the differences in

ethnicity, language and religion, the physical and

psychological improvement was comparable to

that of patients from Australia and Hong Kong. The

efficacy was maintained despite the modifications

made in both Asian programmes to adapt to the local

culture and customs. The challenges of organising

a pain programme were clearly felt by both Asian

groups, as the small sample sizes suggest.

There are significant limitations to this study.

The small sample size recruited from one single

centre made it difficult to extrapolate the findings to

another local chronic pain population. This was also

an observational study although data were collected

prospectively, and there was no control therapy group

for comparison. The data set were primarily physical

and psychological constructs, and some important

social factors associated with return to work were

not collected (such as the ‘blue flag’ factors) and

included in the analyses, hence confounding was

possible. There was also a lack of information about

those who were excluded from the programme and

why, thus significant selection (and self-selection)

bias is present. Prospective randomised controlled

trials are needed to confirm the effectiveness of the

programme, or to compare the efficacy of different

programmes with different designs.

Conclusions

The cognitive behavioural–based pain management

programme improved quality of life and reduced

disability for selected patients with chronic non-cancer

pain in Hong Kong. More patients returned to

work after the programme, and they consumed less

medical resources, with potentially significant social

savings. The strongest association with returning

to work was a brief duration of pain rather than the

baseline intensity of pain, compensable injuries,

physical impairment, or psychological distress of the

subject.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the multidisciplinary

pain management team at the Alice

Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, and the Pain

Management and Research Centre at the University

of Sydney for their assistance in the development

of the COPE programme, data collection, and

manuscript preparation.

References

1. Ng KF, Tsui SL, Chan WS. Prevalence of common chronic

pain in Hong Kong adults. Clin J Pain 2002;18:275-81. Crossref

2. Blyth FM, March LM, Nicholas MK, Cousins MJ. Chronic

pain, work performance and litigation. Pain 2003;103:41-7. Crossref

3. Chou R, Huffman LH; American Pain Society; American

College of Physicians. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute

and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an

American Pain Society/American College of Physicians

clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:492-504. Crossref

4. Nicholas M, Molloy A. Manage your pain: practical and

positive ways of adapting to chronic pain. Australia: ABC

Books; 2001.

5. Man AK, Chu MC, Chen PP, Ma M, Gin T. Clinical

experience with a chronic pain management programme

in Hong Kong Chinese patients. Hong Kong Med J

2007;13:372-8.

6. Leung CM, Wing YK, Kwong PK, Lo A, Shum K. Validation

of the Chinese-Cantonese version of the hospital anxiety

and depression scale and comparison with the Hamilton

Rating Scale of Depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand

1999;100:456-61. Crossref

7. Yap JC, Lau J, Chen PP, et al. Validation of the Chinese Pain

Catastrophizing Scale (HK-PCS) in patients with chronic

pain. Pain Med 2008;9:186-95. Crossref

8. Lim HS, Chen PP, Wong TC, et al. Validation of the Chinese

version of pain self-efficacy questionnaire. Anesth Analg

2007;104:18-23. Crossref

9. Carpenter L, Baker GA, Tyldesley B. The use of the Canadian

occupational performance measure as an outcome of a

pain management program. Can J Occup Ther 2001;68:16-22. Crossref

10. Lam CL, Gandek B, Ren XS, Chan MS. Tests of scaling assumptions

and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version

of the SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1139-47. Crossref

11. Frank JW, Brooker A, DeMaio SE, et al. Disability resulting

from occupational low back pain: Part II: What do we know

about secondary prevention? A review of the scientific

evidence on prevention after disability begins. Spine (Phila

Pa 1976) 1996;21:2918-29. Crossref

12. Lötters F, Burdorf A. Prognostic factors for duration of

sickness absence due to musculoskeletal disorders. Clin J

Pain 2006;22:212-21. Crossref

13. Cheng AS, Hung LK. Socio-demographic predictors of

work disability after occupational injuries. Hong Kong J

Occup Ther 2007;17:45-53. Crossref

14. Buck R, Barnes MC, Cohen D, Aylward M. Common health

problems, yellow flags and functioning in a community

setting. J Occup Rehabil 2010;20:235-46. Crossref

15. Gatchel RJ, Mayer T, Dersh J, Robinson R, Polatin P. The

association of the SF-36 health status survey with 1-year

socioeconomic outcomes in a chronically disabled spinal

disorder population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:2162-70. Crossref

16. Kuijer W, Groothoff JW, Brouwer S, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra

PU. Prediction of sickness absence in patients with chronic

low back pain: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil

2006;16:439-67. Crossref

17. Iles RA, Davison M, Taylor NF. Psychosocial predictors

of failure to return to work in non-chronic non-specific

low back pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med

2008;65:507-17. Crossref

18. Buck R, Porteous C, Wynne-Jones G, Marsh K, Phillips CJ,

Main CJ. Challenges to remaining at work with common health

problems: what helps and what influence do organisational

policies have? J Occup Rehabil 2011;21:501-12. Crossref

19. Hong Kong unemployment rate. Available from: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/hong-kong/unemploymentrate.

Accessed 26 Sep 2014.

20. Luk KD, Wan TW, Wong YW, et al. A multidisciplinary

rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low

back pain: a prospective study. J Ortho Surg (Hong Kong)

2010;18:131-8.

21. Tse MM, Vong SK, Ho SS. The effectiveness of an

integrated pain management program for older persons

and staff in nursing homes. Arch Gerontol Geriatr

2012;54:e203-12. Crossref

22. Cardosa M, Osman ZJ, Nicholas M, et al. Self-management

of chronic pain in Malaysian patients: effectiveness trial

with 1-year follow up. Transl Behav Med 2012;2:30-7. Crossref