A prospective randomised controlled trial of octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and standard suture for wound closure following breast surgery

Hong Kong Med J 2016 Jun;22(3):216–22 | Epub 22 Apr 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154513

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

A prospective randomised controlled trial of

octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and standard

suture for wound closure following breast surgery

Clement TH Chen, FCSHK, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Catherine LY Choi, FCSHK, FHKAM (Surgery)2;

Dacita TK Suen, FCSHK, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Ava Kwong, FCSHK, FHKAM (Surgery)1

1 Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital and Tung Wah Hospital,

Hong Kong

2 Private practice, Hong Kong

Corresponding authors: Dr Clement TH Chen (chenthc@ha.org.hk), Dr Ava Kwong (avakwong@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Several studies have demonstrated

that octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive provides

an equivalent cosmetic outcome as standard

suture for wound closure. This study aimed to compare

octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with standard

suture for wound closure following breast surgery.

Methods: A prospective randomised controlled

trial was conducted in a public hospital in Hong

Kong. A total of 70 female patients, who underwent

elective excision of clinically benign breast lump

between February 2009 and November 2011, were

randomised to have wound closure using either

octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive or standard

wound suture following breast surgery. Wound

complications and cosmetic outcome were measured.

Results: Octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive

achieved wound closure in significantly less time

than standard suturing (mean, 80.6 seconds vs 344.6

seconds; P<0.001). There was no statistical difference

in wound condition or cosmetic outcome although

number of clinic visits, ease of self-showering,

and comfort of dressing significantly favoured

octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive.

Conclusions: Octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive

may be offered as an option for wound closure

following breast surgery.

New knowledge added by this study

- Use of octylcyanoacrylate (OCA) tissue adhesive in wound closure following breast surgery is feasible.

- OCA may be offered as an option for wound closure following breast surgery.

Introduction

In Hong Kong, thousands of patients undergo breast

surgery every year for both benign and malignant

conditions.1 Patients expect a good cosmetic

outcome and satisfactory postoperative wound

management. This is in addition to the expectation

of a cure, or in the case of breast cancer, complete

removal of lesions with optimal survival.

Several studies have demonstrated that

octylcyanoacrylate (OCA) tissue adhesive provides

an equivalent cosmetic outcome to wound suturing

in repair of lacerations,2 3 head and neck surgery,4 plastic surgery,5 and breast surgery.6 7 The OCA tissue adhesives are supplied as monomers in a liquid

form. They polymerise on contact with tissue anions,

forming a strong bond that holds the opposed

wound edges together. The OCA tissue adhesive

usually sloughs off with time. The wound epithelises

within 5 to 10 days and the adhesive does not require

removal.

In-vitro studies have shown that OCA

provides an effective antimicrobial barrier for the

first 72 hours after application.8 It is approved by the

US Food and Drug Administration as a topical skin

adhesive that protects the wound from bacteria. It

also facilitates postoperative wound care as patients

are allowed to shower immediately. There is no need

for suturing, staple removal, or dressings. Higher

patient satisfaction following skin closure with OCA

tissue adhesive compared with sutures has been

observed.6 Studies also show faster wound closure

with OCA.9

This study aimed to assess the outcome of

elective breast surgical incision repair with OCA

tissue adhesive compared with standard wound

suture (SWS). We compared the cosmetic outcome,

complication rates, and patient satisfaction score for

breast incisions in elective surgery closed with OCA

tissue adhesive versus SWS.

Methods

The study was in compliance with the Declaration

of Helsinki and ICH-GCP (International Conference

on Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice). It was

reviewed and approved by the institutional review

boards.

Based on a randomised trial of OCA versus

SWS in breast surgery,5 patient satisfaction in an

OCA group has been reported to be significantly

higher than that of a SWS group. To detect a

difference with a power of 90% and α=0.05, 35

patients were needed for each arm.

A total of 70 female patients, who underwent

elective excision of clinically benign breast lump

between February 2009 and November 2011 in

this randomised controlled trial, were randomly

allocated to have wound closure using either OCA or

SWS with a continuous monofilament subcuticular

method. They were seen on the morning of the

surgery, consented, and randomly allocated to a study

arm. Each randomisation number was computer-generated, sealed in an envelope, and kept in a secure

designated place. At the time of wound closure, the

surgeon would call a third-party nurse to open the

sealed envelope that would determine the method

to be used for wound closure. The surgery was

performed by specialists or surgical trainees under

a specialist’s supervision. Two evaluation forms

were administered to collect information on wound

condition and cosmetic grading by different parties.

Postoperatively, the wound condition was

examined by a surgeon who was not involved in

the study. An evaluation form was completed to

note any indication of (1) wound infection, (2)

dehiscence, (3) oozing, and (4) discharge on day 0-1

(early postoperative period) and day 10-14 (first follow-up).

The cosmetic grading of the surgical wound

was checked on day 30 and 180 by an evaluator

(surgeons not involved in the study or the above

evaluations) who looked for any sign of (1) step-off

borders (edges not on same plane), (2) contour

irregularities (wrinkled skin near wound), (3) margin

separation (gap between sides), (4) edge inversion

(wound not properly everted), and (5) excessive

distortion (swelling/oedema/infection); and (6)

evaluated the overall appearance of the wound.

Patient evaluation of whether the appearance

of the wound was “good” or “bad” over a score of 1

(very bad) to 10 (very good) on day 30 and day 180

was also recorded.

Patients were also asked five questions about

self-care of the wound at the day-30 visit. Questions

were answered and rated on a 5-point Likert scale

(very good, good, neutral, bad, very bad) regarding

(1) pain, (2) ease of caring, (3) self-showering,

(4) frequency of hospital/clinic visits for wound

cleansing, and (5) comfort level of wound dressing.

Statistical analyses

Data were summarised with descriptive statistics.

Means and standard deviations (for numeric

variables) and numbers and percentages (for

categorical variables) were calculated where

appropriate. We checked the normality of the

data and found that it did not follow the normal

distribution. Therefore the Wilcoxon rank sum test

and Fisher’s exact test were applied to determine

any significant difference between the OCA and

SWS groups. All statistical analyses were done

using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US)

and R version 3.0.2 (the R Foundation). All statistical

tests were two-sided and statistical significance was

considered at P<0.05.

Results

A total of 70 patients, half of whom were randomised

to receive OCA or SWS, were entered into this

study. One patient from the suture group was lost

to follow-up and excluded from subsequent analysis,

leaving a total number of 69 patients (35 for OCA

group and 34 for SWS group).

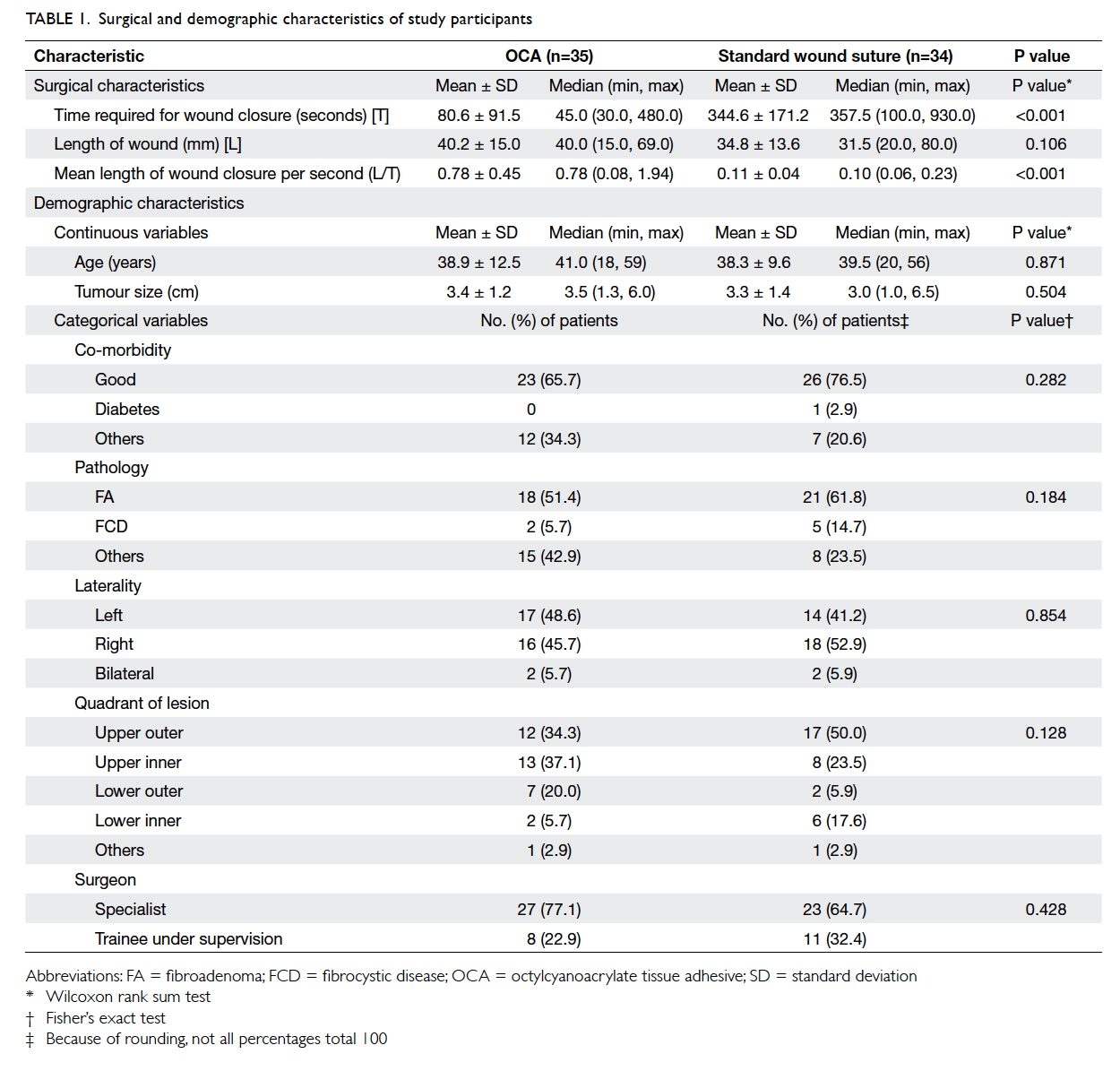

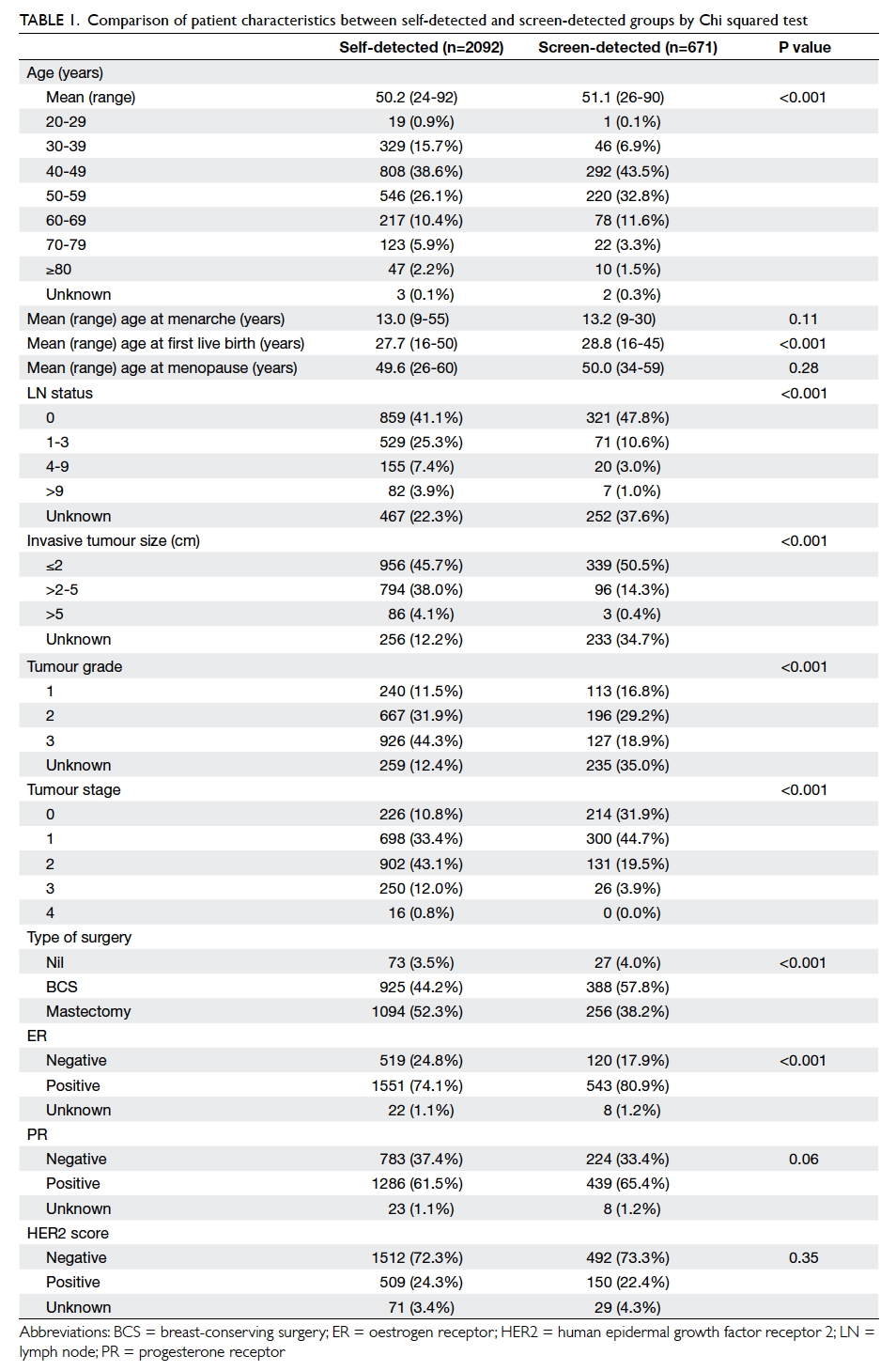

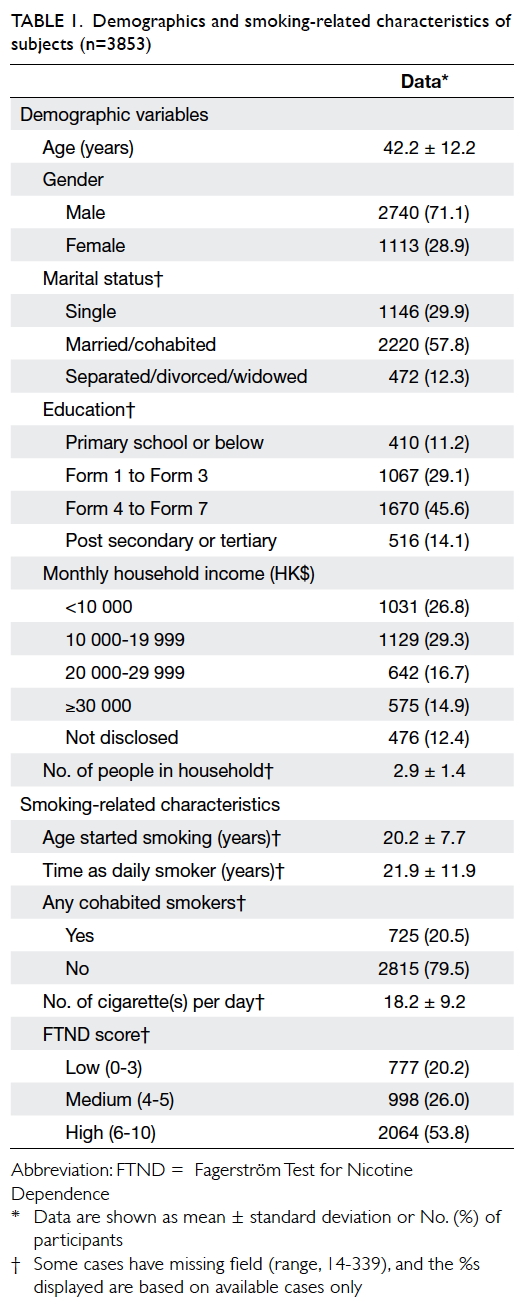

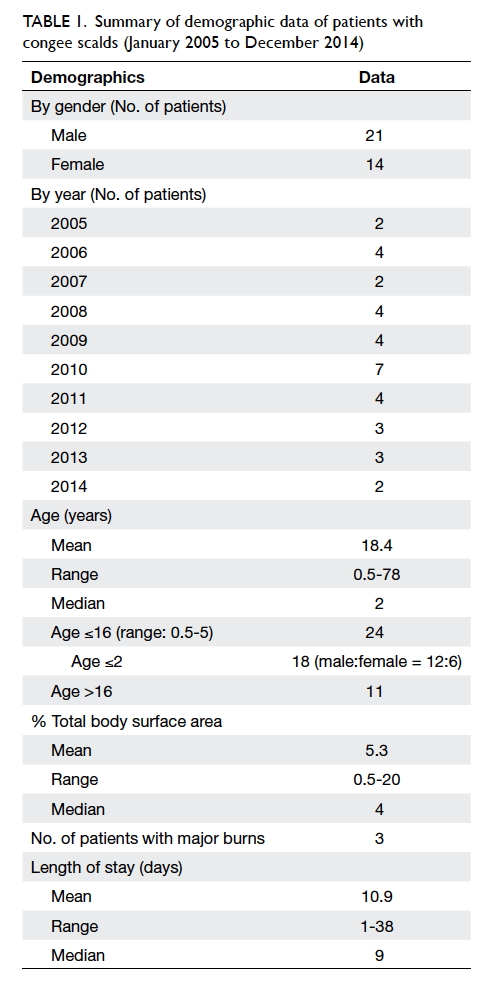

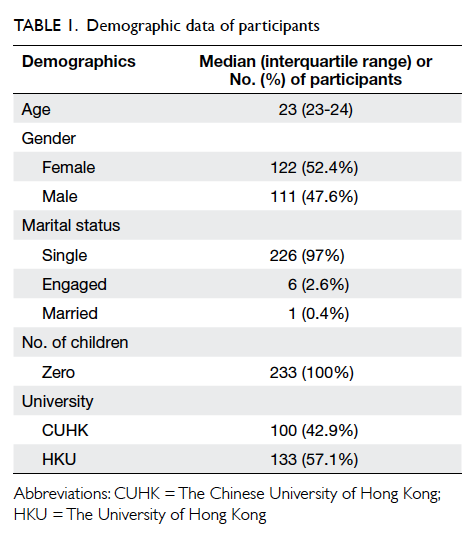

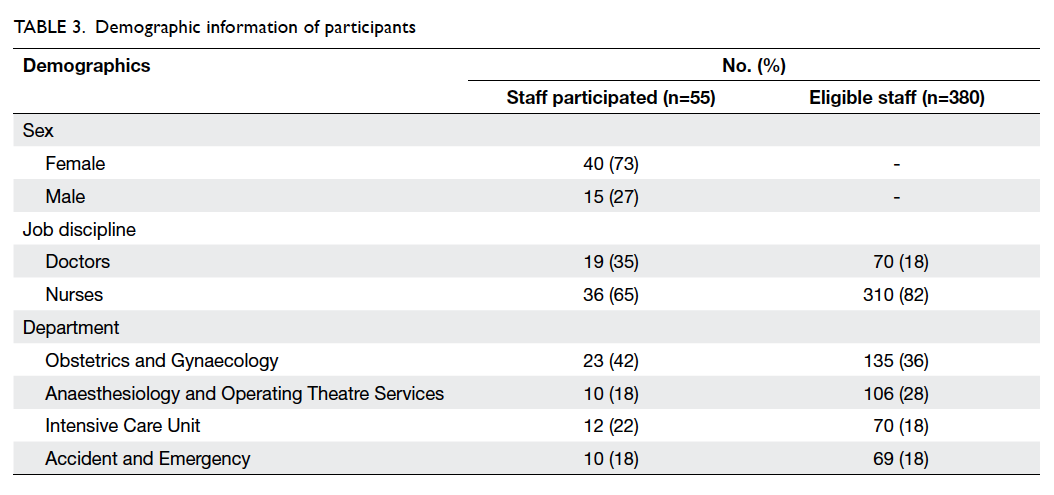

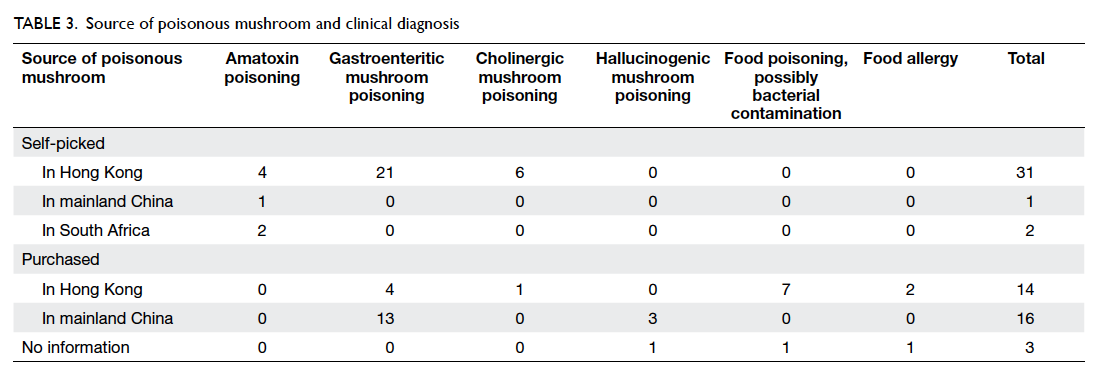

Demographic characteristics

The demographics of the two groups were

comparable. There was no statistical difference in

terms of age, tumour size, co-morbidity including

diabetes, pathology, laterality and location of the

lesion, or the rank of the surgeon involved (Table 1).

Use of OCA was associated with significantly

less time to complete the wound closure process

compared with suture (mean, 80.6 seconds vs 344.6

seconds; P<0.001; Table 1). With similar length of

surgical wound, OCA required 7.1 times less time to

close the wound than suture (P<0.001).

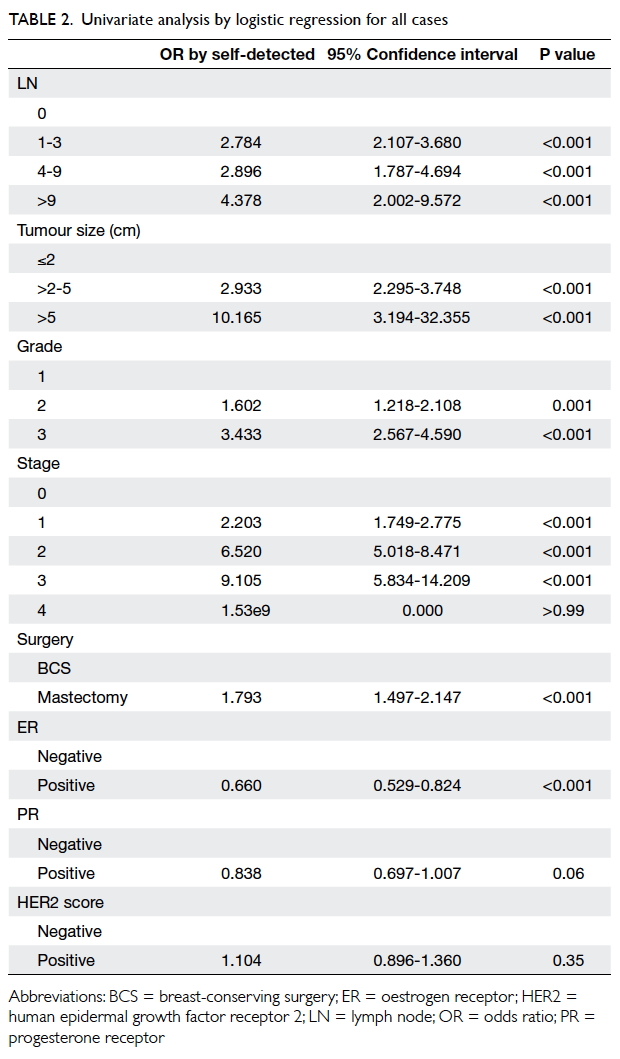

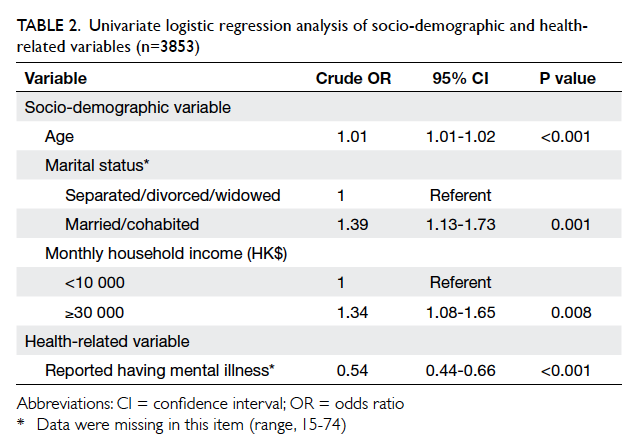

Wound conditions in early postoperative

period (day 0-1) and at first follow-up (day

10-14)

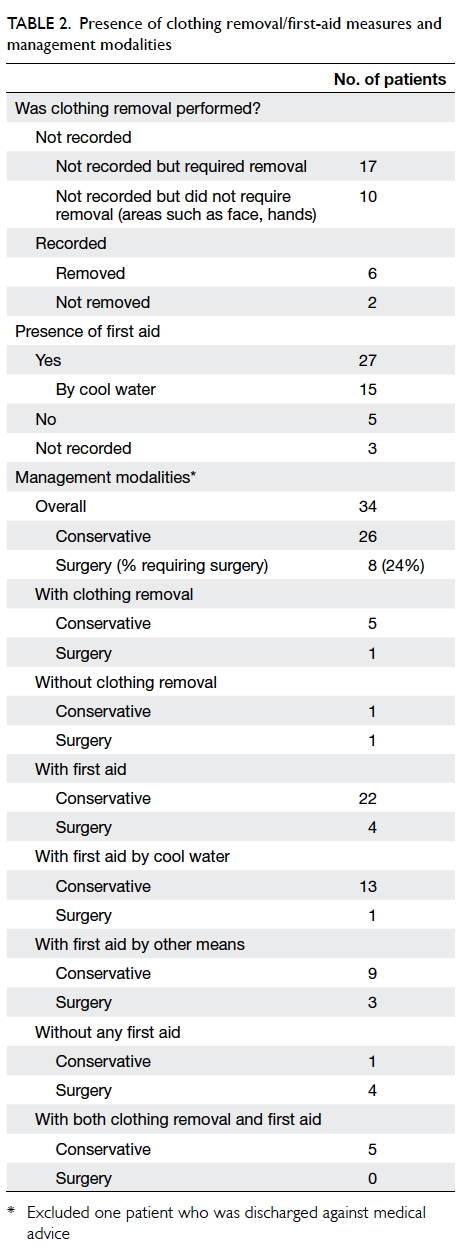

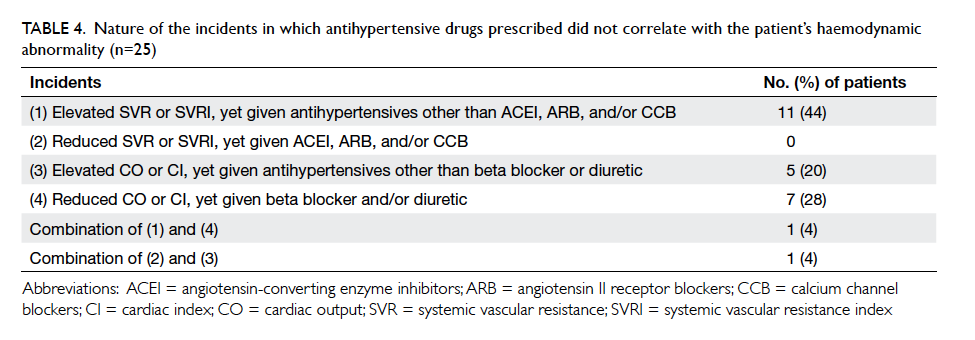

The occurrence of adverse wound condition is

shown in Table 2. There was no unfavourable

condition noticed upon first-day follow-up. Wound

complications on day 10-14 all occurred in the OCA

group.

Table 2. Breast cancer patients with wound complications after wound closure by either OCA (n=35) or standard suture (n=34) on early postoperative period (day 0-1) and upon first follow-up (day 10-14)

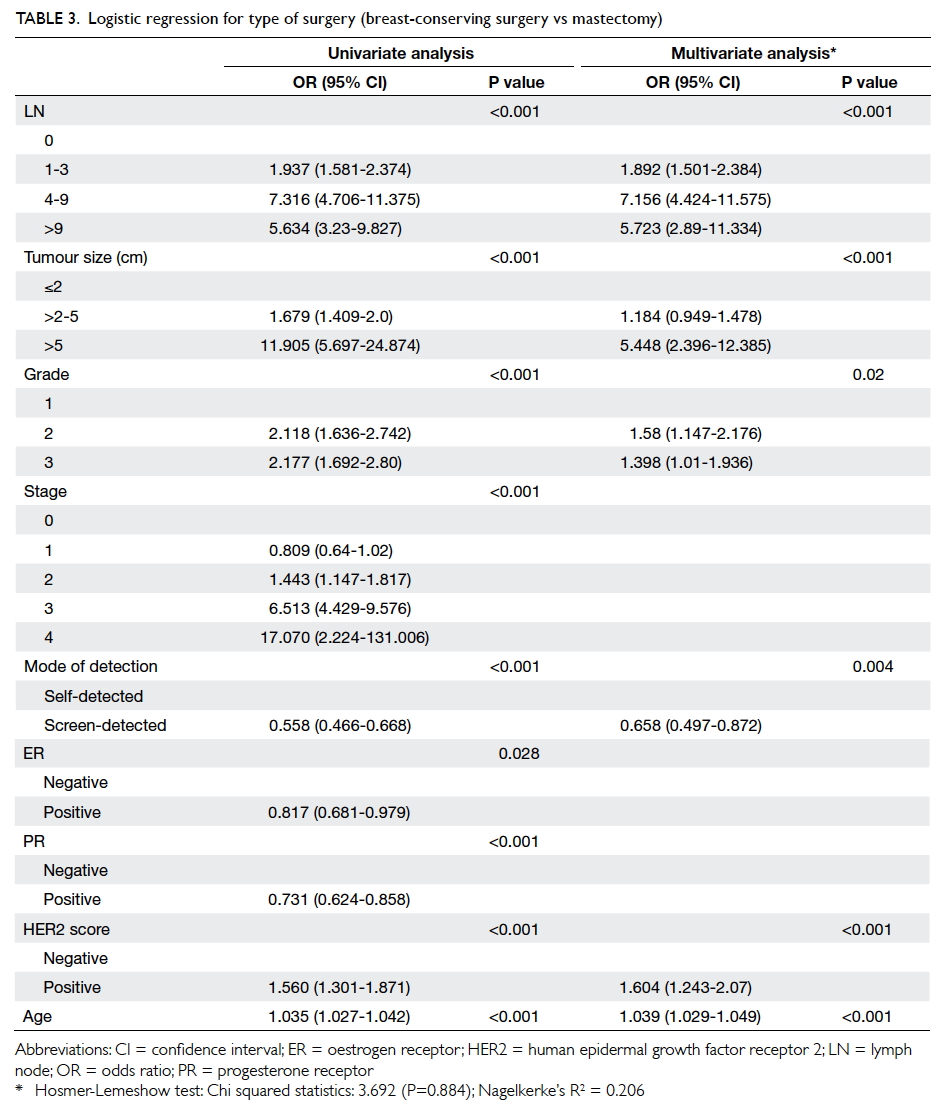

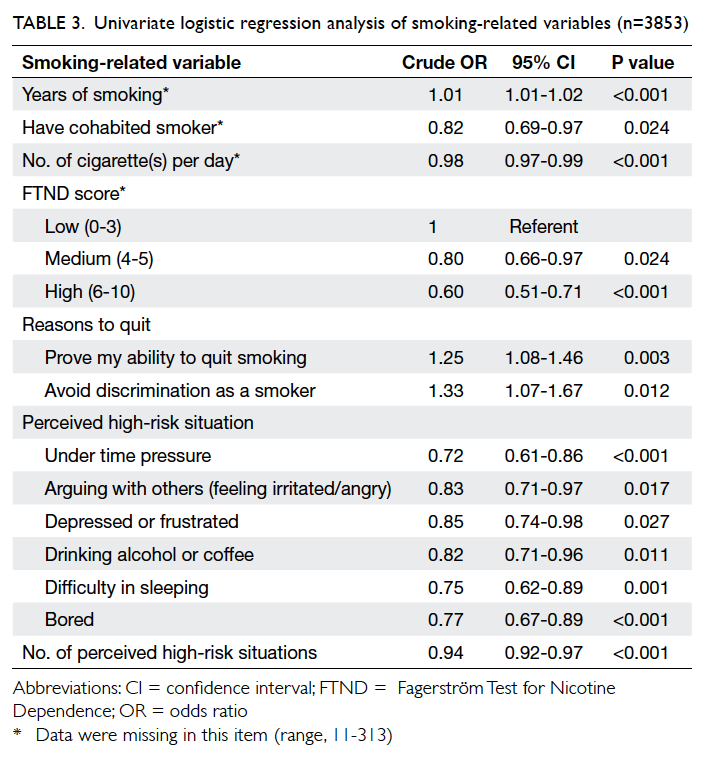

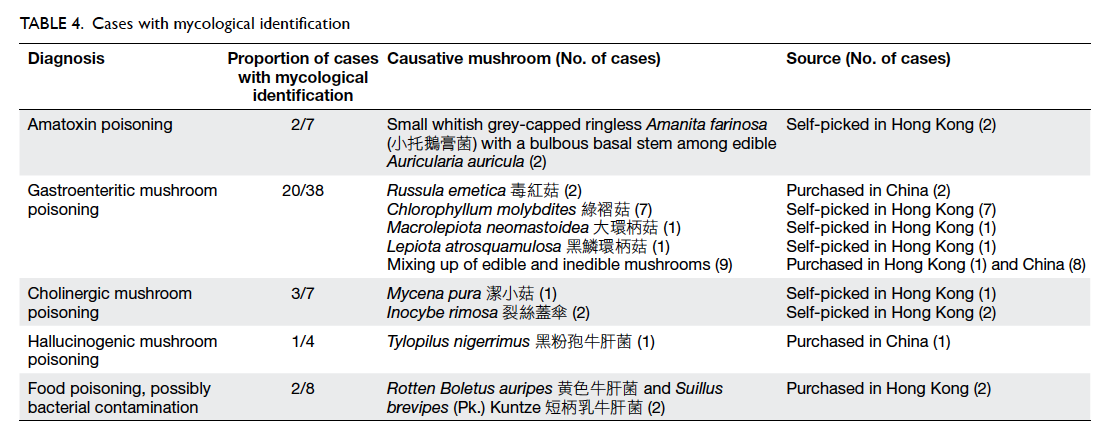

Cosmetic grading by an evaluator and

patients on day 30 and 180

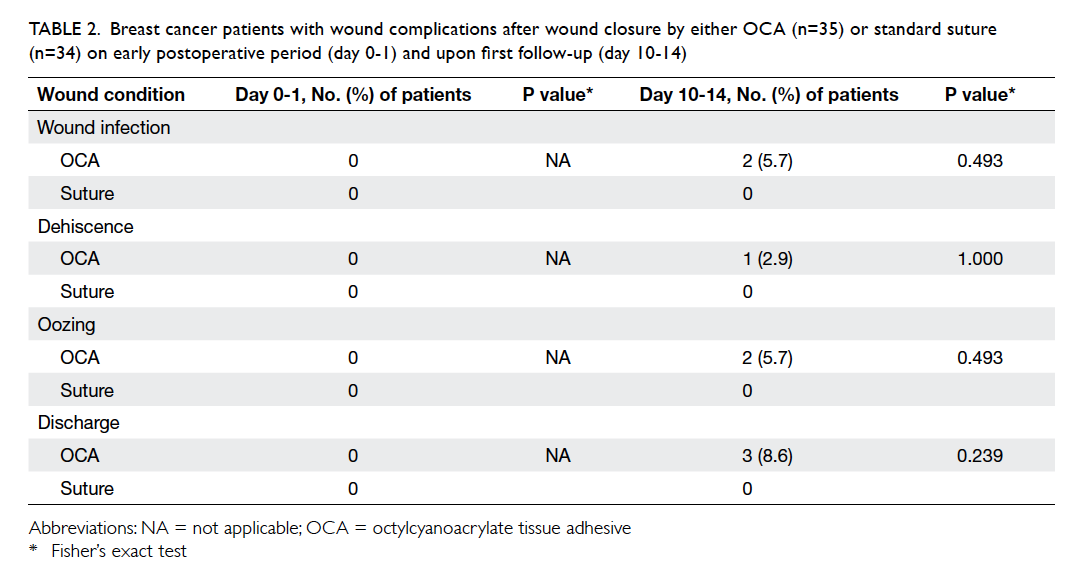

Table 3 summarises the incidence of any wound cosmetic problem on day 30 and 180. Cosmetic

problems were found only on day 30, and were not

confined to any one group. One patient from the

suture group felt that the overall appearance of the

surgical wound on day 30 was bad but subsequently

commented it was “good” on day 180. No bad

comments were received from any patient who had

undergone wound closure with OCA.

Table 3. Breast cancer patients with cosmetic problems with surgical wound closure by either OCA (n=35) or standard suture (n=34), graded by an evaluator on day 30 and day 180

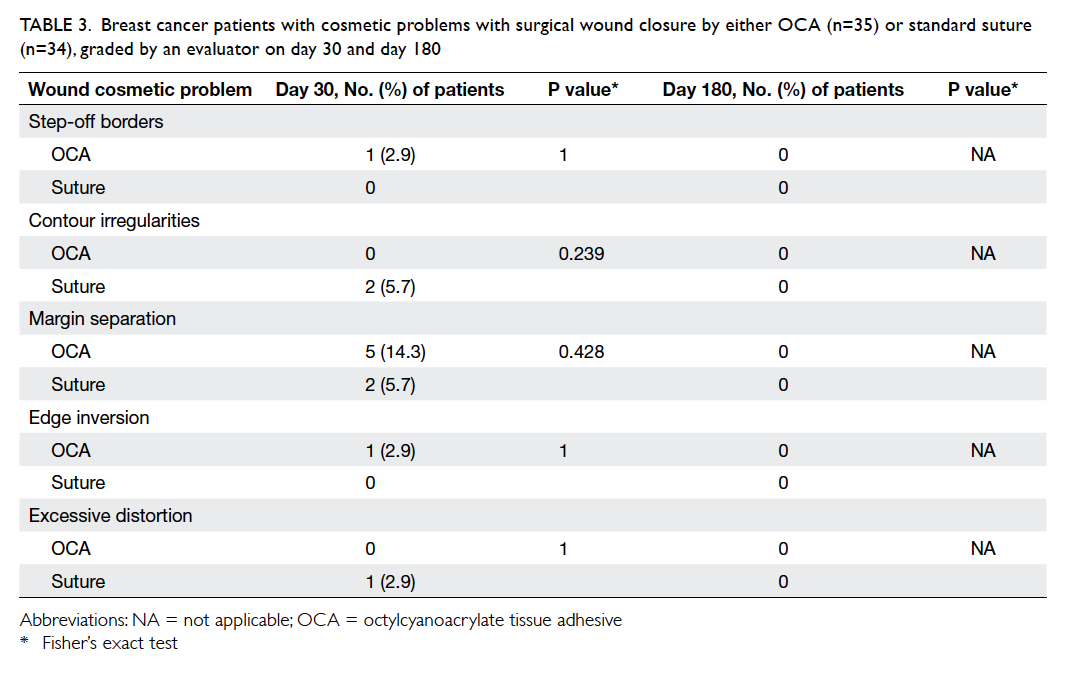

For the patient’s view of cosmetic outcome, a

higher score was given to wounds closed by sutures

compared with OCA on both day 30 and 180,

although the standard deviations were larger in the

OCA group, and the differences were not statistically

significant (Table 4). Higher scores were given on

day 180 compared with day 30 in both groups.

Table 4. Cosmetic grading by breast cancer patients of wounds closed by either OCA or standard suture on day 30 and day 180

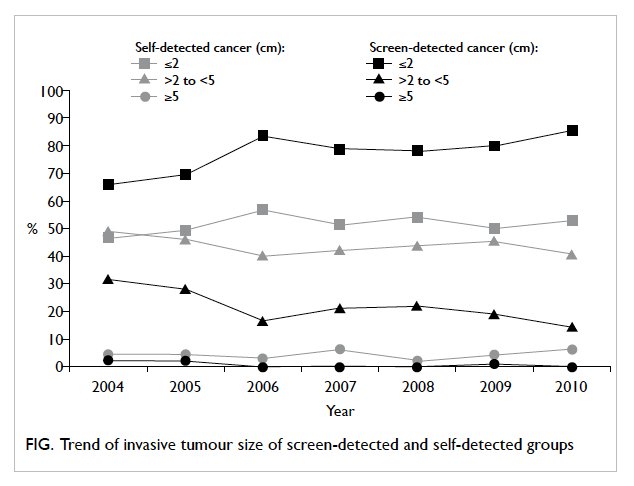

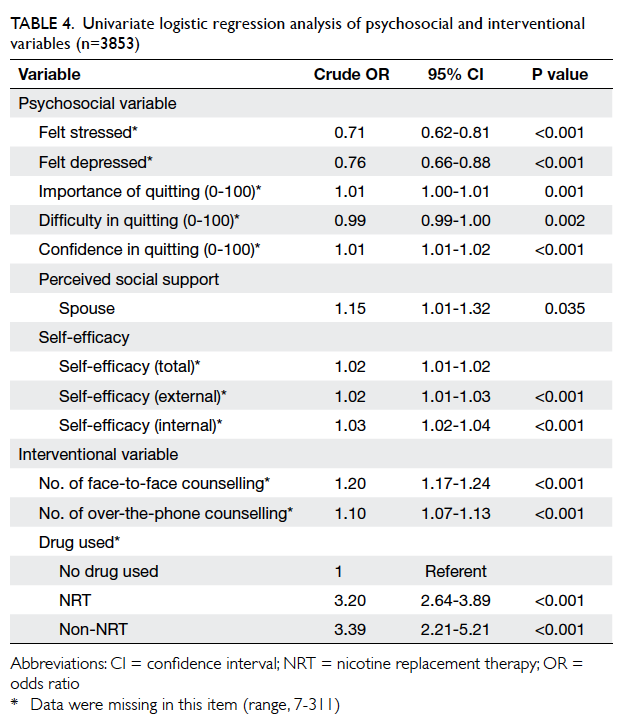

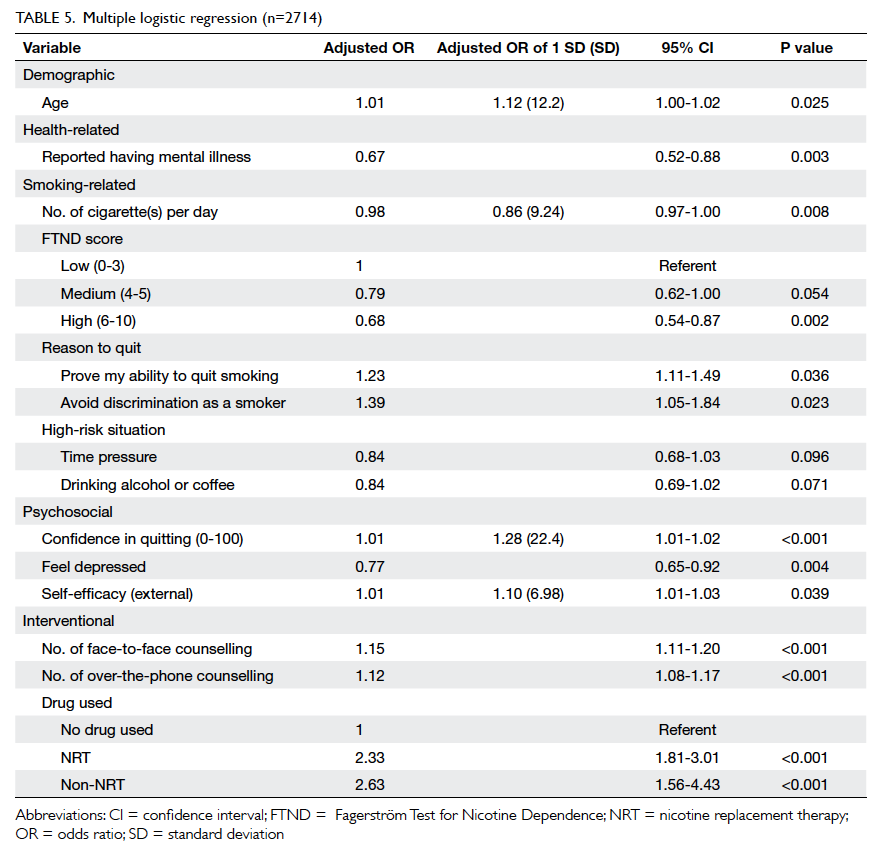

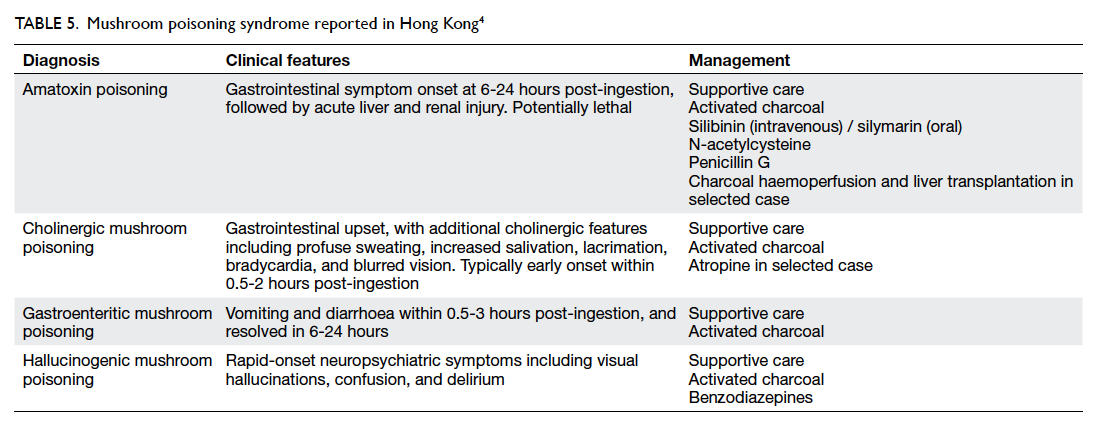

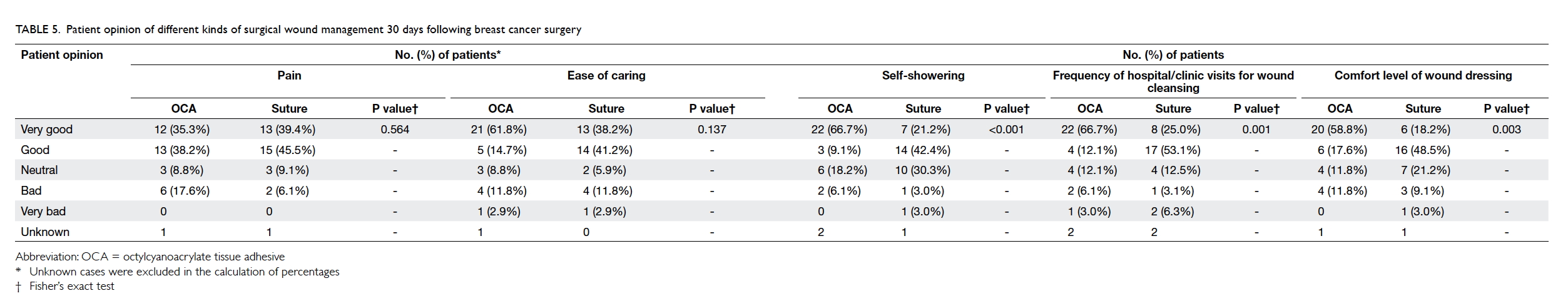

Patients’ opinion of different kinds of wound

management 30 days after surgery

The actual number of hospital or clinic visits was

recorded. Patients in the OCA group required fewer

visits than those in the suture group (16 OCA vs 18

sutures, 1.19 ± 2.66 vs 2.50 ± 4.57; P=0.063). A higher

percentage of patients in the OCA group felt “very

good” on ‘self-showering’ (OCA vs suture, 66.7% vs

21.2%; P<0.001), ‘frequency of hospital/clinic visits

for wound cleansing’ (OCA vs suture, 66.7% vs 25.0%;

P=0.001), and ‘comfort level of wound dressing’

(OCA vs suture, 58.8% vs 18.2%; P=0.003) [Table

5]. More patients in the suture group rated “good”,

instead of “very good” for these three categories. The

same applied for ‘ease of caring’ although statistical

significance was not reached. For patients who

commented “bad” or “very bad”, the percentages

were generally higher from the OCA group. There

was no significant difference between the two groups

for reports about pain (P=0.564).

Table 5. Patient opinion of different kinds of surgical wound management 30 days following breast cancer surgery

Discussion

Tissue adhesive material has long been used in

wound closure in western countries, and offers

the advantages of faster closure, need for less

postoperative wound care, and higher patient

satisfaction.

In this study among Chinese women, we

demonstrated that time required for wound closure

was much less in the OCA group compared with the

SWS group (P<0.001). Although the difference was

significant, time required for wound closure was not

a significant concern for the surgeon.

There were three instances of postoperative

complications in the OCA group. In two patients,

the surgery was performed by a trainee under

supervision, and in one by a specialist. One patient

required secondary suturing 3 weeks later. The other

two were treated conservatively with antibiotics. We

postulate that there is a learning curve for closure

with OCA, thus technical skill and experience of the

surgeon may play a role.

For cosmetic outcome, the score was

comparable in both groups, although slightly higher

in the SWS group. Nonetheless, the difference was

less than 1 point on a scale of 10. The standard

deviation in the OCA group was wider (OCA 2.17

vs SWS 1.36) at day 30 but was not statistically

significant.

For wound problems, margin separation

occurred on postoperative day 30 in five patients

in the OCA group compared with two in the SWS

group. There was no statistical difference in cosmetic

problem grading between the two study groups. It

should be noted that tissue adhesive wound repair

is a manual skill, just like suturing, and requires

practice and careful application. Factors such as

wound oozing or discharge may hinder proper

functioning of the tissue adhesive.

The skin of patients of Chinese or Asian descent

is more prone to keloid scarring and pigmentation,

thus the effect of using tissue adhesives may differ to

that of a western population. A previous study did not

show any difference in the rate of hypertrophic scar

formation.10 In our study, there was no hypertrophic

scar or keloid formation in either group.

There was a significant difference in preference

in terms of self-showering, frequency of hospital/clinic visits, and comfort level of dressing between OCA and SWS groups. These

factors affect patients since they impact on daily

activities and saving of time. On the other hand,

there was no statistical difference in degree of pain,

although the Phi value was very small, thus a larger

sample size may be required to detect any difference.

The sample size for all other values was adequate.

In terms of cost, a study in Hong Kong has

shown that tissue adhesive is more expensive than

SWS,11 but may be more cost-effective from a social

viewpoint in terms of superior cosmetic outcome

and overall patient satisfaction.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

First, this was a prospective randomised study confined to closure of benign breast lump wounds and thus not necessarily applicable to all surgical

wounds. We did not determine the number of

eligible patients for the study, or note how many of

them refused to take part. This may have led to self-selection

bias. Second, the operation was performed

by different surgeons of different seniority, and may

have led to varying levels of surgical technique. This

was not shown to be statistically significant but the

sample size was not designed to reflect this. Lastly,

during wound evaluation, the surgeon might not have

been totally blind to the type of closure if sutures

or stitch marks were visible. This may be a cause

of blinding bias. The use of a scoring scale is also a

subjective evaluation, and may be influenced by the

patient’s mood and other factors.

Conclusions

The use of OCA should be discussed and offered to

patients as an option for wound closure in breast

surgery. It achieves faster wound closure, is not

inferior to standard wound closure, has a higher

comfort level, and requires less frequent clinic

visits. Understanding cost-effectiveness is essential

in medical care, thus OCA should be offered as an

option to be provided as a self-financed item in the

public sector where it is now widely available.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Jack Chau and Miss Fidelia Wong for

performing the early statistical analysis, and Mr Ling-hiu

Fung and Mr Wing-pan Luk of the Hong Kong

Sanatorium & Hospital for the later review and re-running

of the statistical analysis methods. We also

thank Ethicon, Johnson and Johnson Company for

providing the OCA study material.

Declaration

Johnson and Johnson provided the study material.

No other conflict of interests was declared by

authors.

References

1. Top ten cancers in 2013. Hong Kong Cancer Registry.

Available from: http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/statistics.html. Accessed Jan 2016.

2. Singer AJ, Quinn JV, Clark RE, Hollander JE; TraumaSeal

Study Group. Closure of lacerations and incisions with

octylcyanoacrylate: a multicenter randomized controlled

trial. Surgery 2002;131:270-6. Crossref

3. Chow A, Marshall H, Zacharakis E, Paraskeva P,

Purkayastha S. Use of tissue glue for surgical incision

closure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Surg 2010;211:114-25. Crossref

4. Maw JL, Quinn JV, Wells GA, et al. A prospective

comparison of octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and

suture for the closure of head and neck incisions. J

Otolaryngol 1997;26:26-30.

5. Toriumi DM, O’Grady K, Desai D, Bagal A. Use of octyl-2-cyanoacrylate for skin closure in facial plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:2209-19. Crossref

6. Gennari R, Rotmensz N, Ballardini B, et al. A prospective,

randomized, controlled clinical trial of tissue adhesive

(2-octylcyanoacrylate) versus standard wound closure in

breast surgery. Surgery 2004;136:593-9. Crossref

7. Nipshagen MD, Hage JJ, Beekman WH. Use of 2-octylcyanoacrylate

skin adhesive (Dermabond) for wound

closure following reduction mammaplasty: a prospective,

randomized intervention study. Plast Reconstr Surg

2008;122:10-8. Crossref

8. Quinn JV, Osmond MH, Yurack JA, Moir PJ. N-2-butylcyanoacrylate: risk of bacterial contamination with

an appraisal of its antimicrobial effects. J Emerg Med

1995;13:581-5. Crossref

9. Soni A, Narula R, Kumar A, Parmar M, Sahore M,

Chandel M. Comparing cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and

conventional subcuticular skin sutures for maxillofacial

incisions—a prospective randomized trial considering

closure time, wound morbidity, and cosmetic outcome. J

Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013;71:2152.e1-8. Crossref

10. Wilson AD, Mercer N. Dermabond tissue adhesive versus

Steri-Strips in unilateral cleft lip repair: an audit of infection

and hypertrophic scar rates. Cleft Palate Craniofac J

2008;45:614-9. Crossref

11. Wong EM, Rainer TH, Ng YC, Chan MS, Lopez V. Cost-effectiveness

of Dermabond versus sutures for lacerated

wound closure: a randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong

Med J 2011;17 Suppl 6:4-8.