Impact of 18FDG PET and 11C-PIB PET brain imaging on the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in a regional memory clinic in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Med J 2016 Aug;22(4):327–33 | Epub 17 Jun 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154707

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Impact of 18FDG PET and 11C-PIB PET brain imaging on the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in a regional memory clinic in Hong Kong

YF Shea, MRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Joyce Ha, BSc1;

SC Lee, BHS (Nursing)1;

LW Chu, MD, FRCP1,2

1 Division of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine, LKS Faculty of Medicine,

The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 The Alzheimer’s Disease Research Network, SRT Ageing, The University

of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YF Shea (elphashea@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: This study investigated the improvement

in the accuracy of diagnosis of dementia subtypes

among Chinese dementia patients who underwent

[18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission

tomography (18FDG PET) with or without carbon 11–labelled Pittsburgh

compound B (11C-PIB).

Methods: This case series was performed in the

Memory Clinic at Queen Mary Hospital, Hong

Kong. We reviewed 109 subjects (56.9% were female) who

received PET with or without 11C-PIB between January

2007 and December 2014. Data including age, sex,

education level, Mini-Mental State Examination

score, Clinical Dementia Rating scale score,

neuroimaging report, and pre-/post-imaging clinical

diagnoses were collected from medical records. The

agreement between the initial and post-PET with or

without 11C-PIB dementia diagnosis was analysed by the

Cohen’s kappa statistics.

Results: The overall accuracy of initial clinical

diagnosis of dementia subtype was 63.7%, and

diagnosis was subsequently changed in 36.3% of

subjects following PET with or without 11C-PIB. The

rate of accurate initial clinical diagnosis (compared

with the final post-imaging diagnosis) was 81.5%,

44.4%, 14.3%, 28.6%, 55.6% and 0% for Alzheimer’s

disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal

dementia, vascular dementia, other dementia, and mixed dementia, respectively. The agreement

between the initial and final post-imaging dementia

subtype diagnosis was only fair, with a Cohen’s kappa

of 0.25 (95% confidence interval, 0.05-0.45). For the

21 subjects who underwent 11C-PIB PET imaging, 19%

(n=4) of those with Alzheimer’s disease (PIB positive)

were initially diagnosed with non–Alzheimer’s

disease dementia.

Conclusions: In this study, PET with or without

11C-PIB brain imaging helped improve the accuracy of

diagnosis of dementia subtype in 36% of our patients

with underlying Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with

Lewy bodies, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal

dementia.

New knowledge added by this study

- Positron emission tomography (PET) with or without Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) brain imaging helps improve the accuracy of dementia subtype diagnosis in Chinese patients.

- PET with or without PIB brain imaging should be considered in patients with dementia who attend the memory clinic, especially if there is diagnostic difficulty.

Introduction

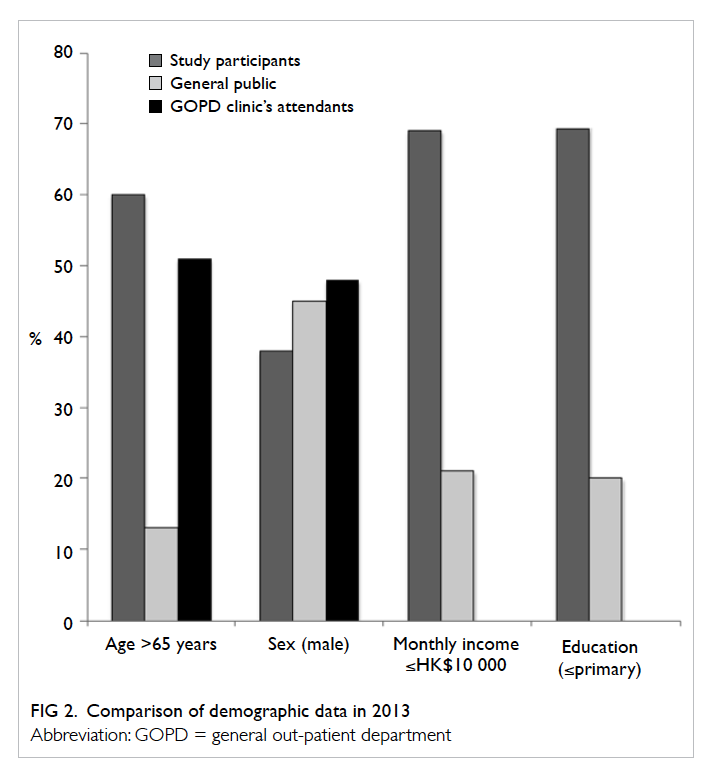

With ageing of the world’s population, the prevalence

of dementia increases: 46.8 million people worldwide

were living with dementia in 2015. This is projected to

reach 74.7 million in 2030 and 131.5 million in 2050,

with 60% suffering from Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1

In Hong Kong, the prevalence of mild dementia has

been reported to be 8.9% for adults aged 70 years or

over, with 64.6% suffering from AD.2 Appropriate

management of demented patients begins with

correct diagnosis of dementia subtype that allows

earlier implementation of disease-specific treatment.

In particular, cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) or N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists are mostly

suitable for the treatment of AD. The current clinical

diagnostic guidelines for various types of dementia

have limited sensitivities and specificities, however.

The sensitivity and specificity of clinical diagnostic

criteria for AD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB),

and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) have been

reported as 81% and 70%, 50% and 80%, 85% and

95%, respectively.3 4 5 6 In the most recent diagnostic

criteria for AD, additional use of biomarkers of AD

has been recommended by the National Institute

on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association to improve

the accuracy of AD diagnosis.3 Biomarkers for the

diagnosis of AD include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF),

amyloid pathological imaging (eg carbon 11–labelled

Pittsburgh compound B [11C-PIB] positron emission

tomography [PET]), and functional imaging (eg [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose [18F-FDG] PET) that

yield sensitivities and specificities of at least 90% and

85%, respectively in the diagnosis of AD, DLB, and

FTD.3 7 8 9 10 11 Because of the invasive nature of lumbar puncture in the collection of CSF, neuroimaging

modalities such as 18F-FDG PET and 11C-PIB PET

are more accepted in routine clinical practice to

improve the diagnosis of dementia subtype.

The most common functional neuroimaging is

with 18F-FDG12 and the most common pathological

neuroimaging is with 11C-PIB.13 These molecular

imaging markers are imaged using PET. The 18F-FDG

measures metabolic activity of the brain; 18F-FDG

PET distinguishes well between AD and non-AD

dementia.11 In a systematic review, the sensitivity

and specificity for 18F-FDG PET in distinguishing

between AD and DLB was 83%-99% and 71%-93%,

respectively; and the sensitivity and specificity for

18F-FDG PET in distinguishing between AD and

FTD was 97.6%-99% and 65%-86%, respectively.11 In

the same systematic review, 18F-FDG PET predicted

patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

deteriorating into dementia with sensitivity and

specificity of 81%-82% and 86%-90%, respectively.11

Besides, 11C-PIB can detect the presence of fibrillar

amyloid plaques that are a neuropathological marker

of AD.13 Correlation studies with neuropathology

have shown a sensitivity of 90% and specificity

of 100%; 11C-PIB can reasonably distinguish AD

from other types of dementia, eg FTD.13 Using

neuropathology as the gold standard, the sensitivity

and specificity was 89% and 83%, respectively.13

The presence of 11C-PIB retention also predicts the

progression of patients with MCI: 50% progress

to AD in 1 year and 80% progress to AD within 3

years.14

Previous studies with 18F-FDG and 11C-PIB

PET have focused on highly selected diagnostic

groups, and only a few studies have studied their

impact in the routine clinical setting of a memory

clinic at a tertiary university hospital. The latter are

referral centres, and often encounter patients with

complicated diagnostic issues. Ossenkoppele et al15

reported a cohort of 145 patients who underwent

18F-FDG and 11C-PIB PET after clinical assessment.

Change in clinical diagnosis was required in 23% with

the diagnostic confidence increased from a mean of

71% to 87%. Diagnosis remained unchanged in 96%

after PET over the next 2 years.15 In seven patients

with MCI and positive amyloid deposition on 11C-PIB

PET, six progressed to AD during follow-up (5 had

AD pattern of hypometabolism on 18F-FDG PET).15

In a retrospective study of 94 patients with MCI or

dementia, Laforce et al16 showed that 18F-FDG PET

brain scan led to a change in diagnosis in 29% of

patients, and reduced the frequency of atypical or

unclear diagnoses from 39.4% to 16%.

To the best of our knowledge, there are

no published data on the impact of molecular

neuroimaging on accuracy of diagnosis of AD or

other dementias in the Chinese population. We

hypothesised that brain 18F-FDG with or without

11C-PIB PET imaging can improve the accuracy

of diagnosis of common dementia subtypes in a

memory clinic. The objective of this study was to

investigate the impact of brain 18F-FDG with or

without 11C-PIB imaging in improving the accuracy

of diagnosis of dementia subtype in a local memory

clinic in Hong Kong.

Methods

This was a retrospective study conducted at the

Memory Clinic of Queen Mary Hospital, the

University of Hong Kong. Patients were referred by

general practitioners, neurologists, geriatricians,

surgeons, or psychiatrists. All patient records

between January 2007 and December 2014 were

reviewed. Inclusion criteria were a clinical diagnosis

of MCI, dementia of any type, or unclassifiable

dementia; and 18F-FDG with or without 11C-PIB

PET performed within 3 months after the initial

clinical diagnosis. The initial clinical assessment was

performed by a geriatrician experienced in dementia

care and included detailed history taking from

primary carers of the patient, physical examination,

cognitive assessment, and laboratory studies

(including thyroid function test, vitamin B12 level,

folate level, and syphilis serology [Venereal Disease

Research Laboratory]). Clinical criteria for AD, FTD,

DLB, and vascular dementia (VaD) were employed to

establish the clinical diagnosis initially, without using

any biomarker. The diagnosis of different dementia

subtype before neuroimaging was based on

the respective diagnostic guidelines. Patients with

AD were diagnosed according to the NINCDS-ADRDA

(National Institute of Neurological

and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders

Association) diagnostic criteria.17 Patients with DLB

were diagnosed by the McKeith criteria.4 Behavioural

variant (bv) of FTD was diagnosed by revised

diagnostic criteria reported by the International

bvFTD Criteria Consortium5 and language variant

of FTD was diagnosed by latest published criteria.6

Patients with VaD were diagnosed according to the

criteria of the NINDS-AIREN (National Institute

of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/Association

Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement

en Neurosciences).18 In this study, we reviewed the

medical records of eligible subjects and collected

data including age, sex, education level, Mini-Mental

State Examination score, Clinical Dementia Rating scale score,

molecular imaging report including the standardised

uptake value ratio (SUVR) of 11C-PIB PET, and the

pre- and post-imaging diagnoses. For patients who

were diagnosed with MCI, their progression during

subsequent follow-up visits was also reviewed.

The need for 18F-FDG with or without 11C-PIB

PET was determined by the geriatrician who

performed the initial clinical assessment. The images

were evaluated by a radiologist with more than 10

years of experience in reading PET scans. Dementias

were classified using the generally accepted criteria.

Patients were fasted for at least 4 hours before the

PET. The serum glucose level was measured in all

patients. For 18F-FDG PET, the patient was rested

in a dimly lit room with eyes closed for 30 minutes

prior to injection of 18F-FDG via a venous catheter.

Another 30 minutes of rest was observed before

starting the acquisition. The acquired data were

semi-quantitatively compared with age-stratified

normal controls using three-dimensional stereotactic

surface projections. For PIB imaging, acquisition was

performed at 5 minutes and 35 minutes after 11C-PIB

injection via a venous catheter, and SUVR images of

11C-PIB between 5 and 35 minutes were generated.

Cerebellar grey matter was chosen as reference

tissue. In this study, 11C-PIB PET scans were rated as

positive (PIB+; if binding occurred in more than one

cortical brain region; ie frontal, parietal, temporal, or

occipital) or negative (PIB–; if predominantly white

matter binding).

The pattern of 18F-FDG PET hypometabolism

that is suggestive of each subtype of dementia is as

follows6 12 19:

(1) AD—uni- or bi-lateral parietotemporal

hypometabolism with posterior cingulate

gyrus involvement or bilateral parietal and

precuneal hypometabolism.

(2) DLB—same as AD with added hypometabolism

in occipital lobes.

(3) bvFTD—uni- or bi-lateral frontotemporal

hypometabolism with or without less-severe

parietal hypometabolism.

(4) Semantic dementia—anterior temporal lobe

hypometabolism.

(5) Progressive non-fluent aphasia—left posterior

frontoinsular hypometabolism.

(6) VaD—well-defined focal defects not fitting the

above described patterns.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used for data analyses.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ±

standard deviation or median (interquartile range)

as appropriate. Categorical data were expressed as

number and percentages. The agreement between

pre- or post-imaging diagnoses of dementia subtype

was analysed by the Cohen’s kappa (κ) statistic. The

Cohen’s κ reflected the degree of agreement: <0 = no

agreement, 0-0.20 = slight agreement, 0.21-0.40 = fair

agreement, 0.41-0.60 = moderate agreement, 0.61-0.80 = substantial agreement, and 0.81-1.00 = almost

perfect agreement. All analyses were performed

with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 18.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US).

Results

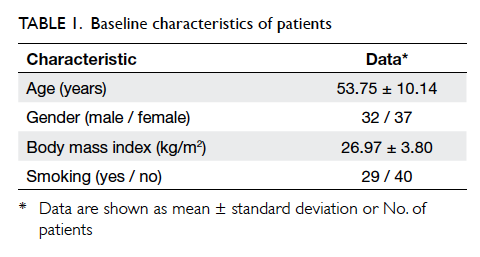

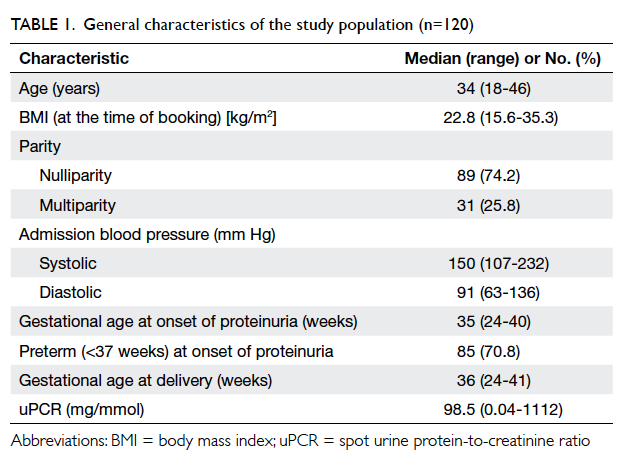

A total of 109 patients (56.9% were female) were recruited of whom 102

had dementia and seven had MCI. Both 18F-FDG

and 11C-PIB PET data were available for 45 (41.3%)

patients, and 64 patients underwent 18F-FDG only.

The final diagnosis of the 102 demented patients

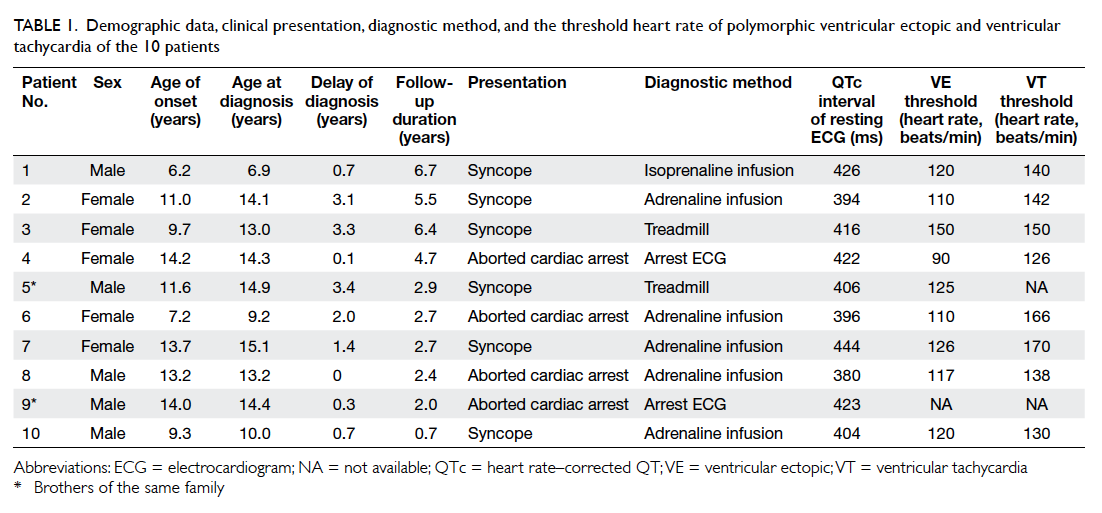

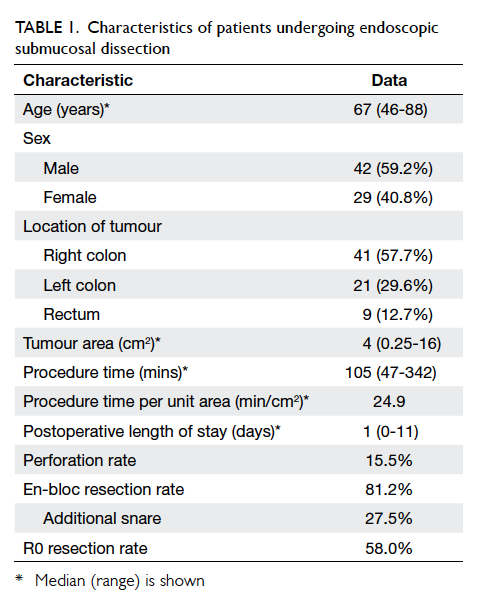

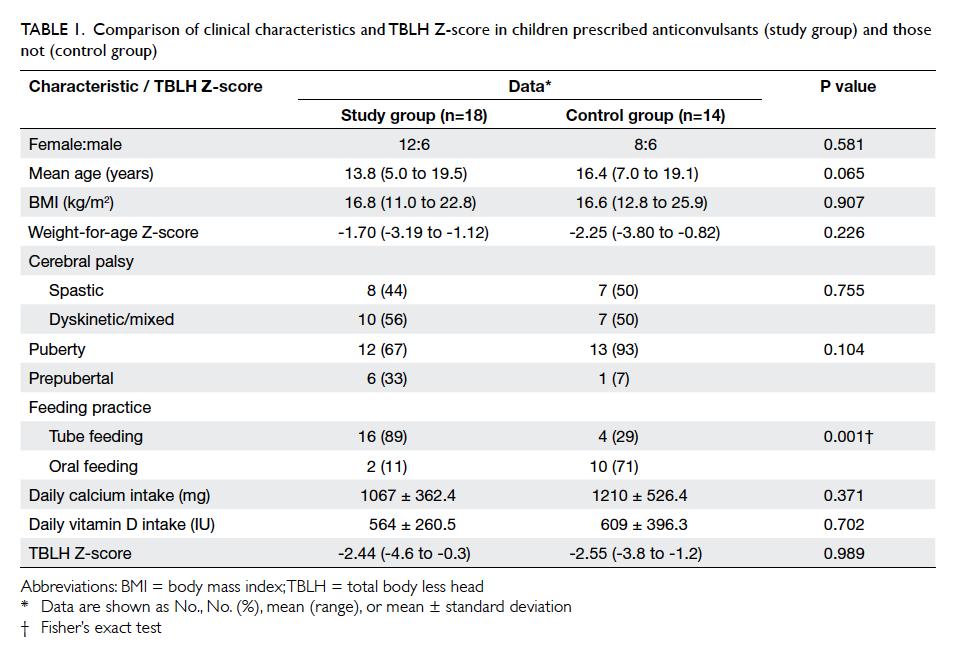

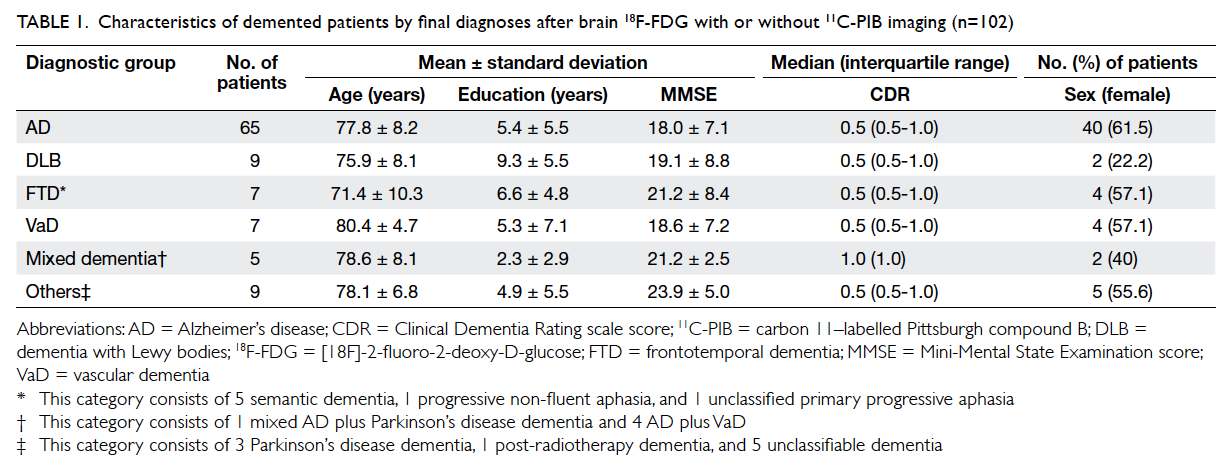

after neuroimaging is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of demented patients by final diagnoses after brain 18F-FDG with or without 11C-PIB imaging (n=102)

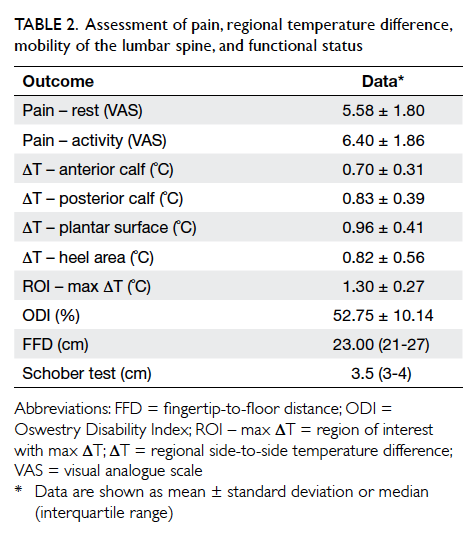

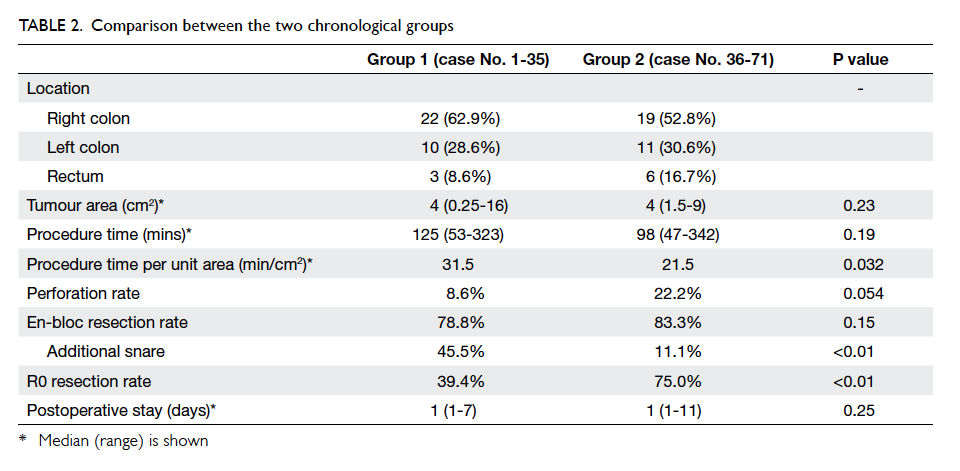

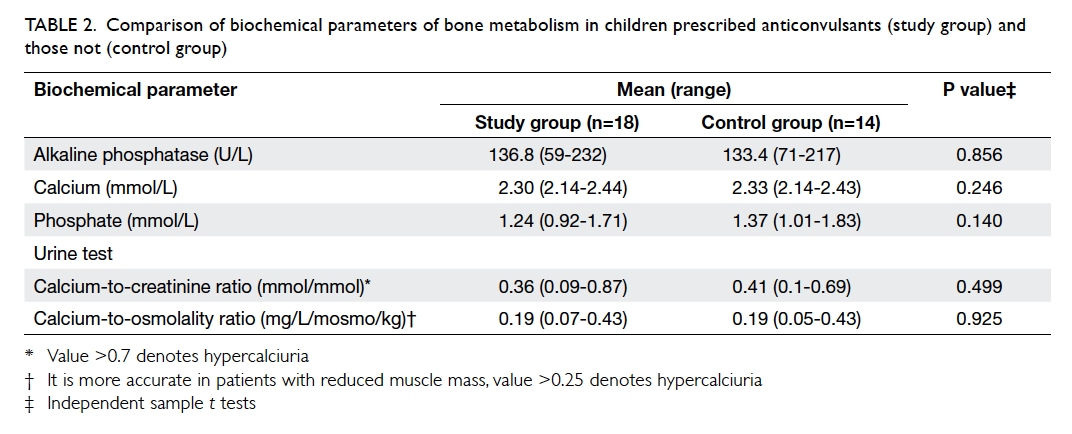

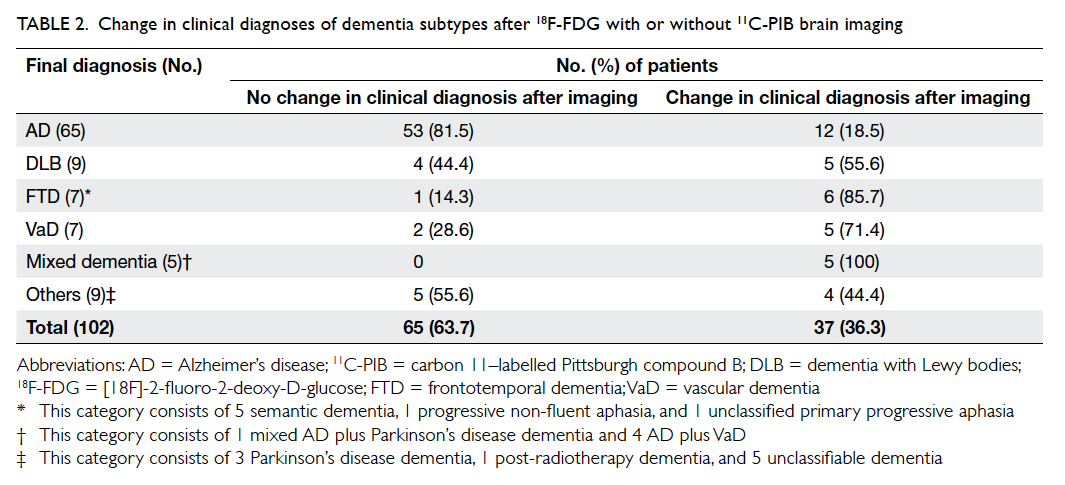

The accuracy of clinical diagnoses is

summarised in Table 2. Overall, PET scans confirmed

the clinical impression in 63.7% of patients, and

corrected the diagnosis in 36.3%. Using the result

of PET scan as the gold standard, the frequency of

accurate initial clinical diagnosis was low for FTD,

VaD, and mixed dementia (14.3%, 28.6%, and 0%,

respectively). The accuracy of clinical diagnosis for

AD and DLB was 81.5% and 44.4%, respectively. After

excluding subjects with an initial MCI diagnosis, the

agreement between the initial and final post-imaging

dementia diagnosis was only fair, with a Cohen’s κ of

0.25 (95% confidence interval, 0.05-0.45).

Table 2. Change in clinical diagnoses of dementia subtypes after 18F-FDG with or without 11C-PIB brain imaging

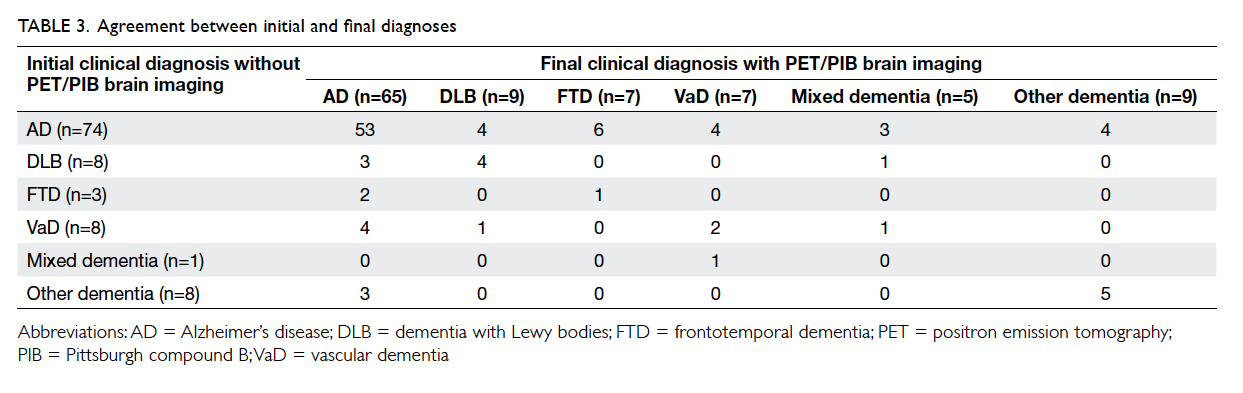

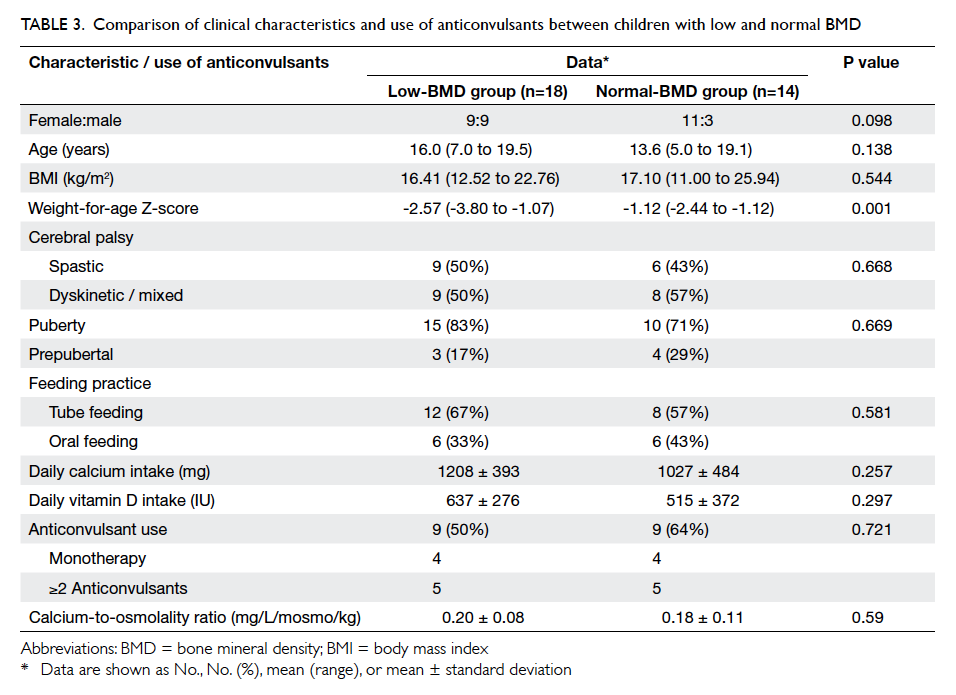

Table 3 lists the diagnosis of subjects before

and after the availability of 18F-FDG with or without

11C-PIB PET neuroimaging. For subjects with a final

diagnosis of AD (n=65), 18.5% (n=12) were initially

diagnosed with non-AD dementia (including 3 with

DLB, 2 with FTD, 4 with VaD, and 3 with other

dementia) and subsequently received symptomatic

AD therapy (ie ChEIs and/or memantine). For

the 21 subjects who underwent PIB PET imaging,

19% (n=4) of those with AD (PIB+) were initially

diagnosed with non-AD dementia. For subjects

with an initial diagnosis of AD (n=74), 28.4% (n=21)

had a change in diagnosis (including 4 DLB, 6 FTD,

4 VaD, 3 mixed AD plus VaD, and 4 with other

dementia). Excluding subjects with DLB and mixed

AD plus VaD, 13.7% of all subjects (14 out of 102)

had discontinued their previous symptomatic AD

therapy. For subjects with a final diagnosis of FTD

(n=7), 85.7% (n=6) were initially misdiagnosed as

AD. For subjects with a final diagnosis of DLB (n=9),

44.4% (n=4) were misdiagnosed as AD.

Five patients were diagnosed with unclassifiable

dementia following neuroimaging, which comprised

four females and one male with a mean age of

78 ± 9.4 years. All presented with amnesia. In

addition, one patient presented with apraxia and

dysexecutive syndrome and another presented with

hyperorality. All of them were PIB-. An AD pattern

of hypometabolism was present in four patients (2

with hypometabolism in posterior cingulate gyrus

and 2 with hypometabolism in temporoparietal

lobes). Isolated hypometabolism in the temporal

lobes was present in one patient.

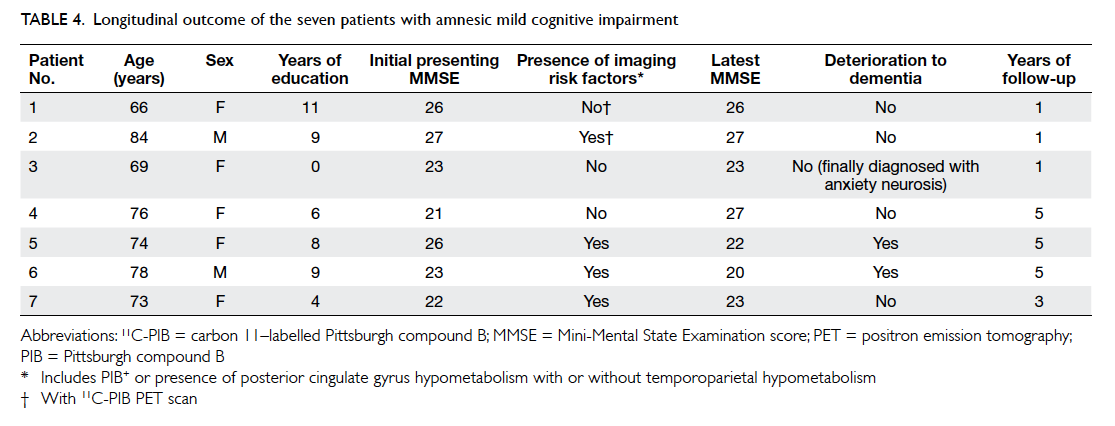

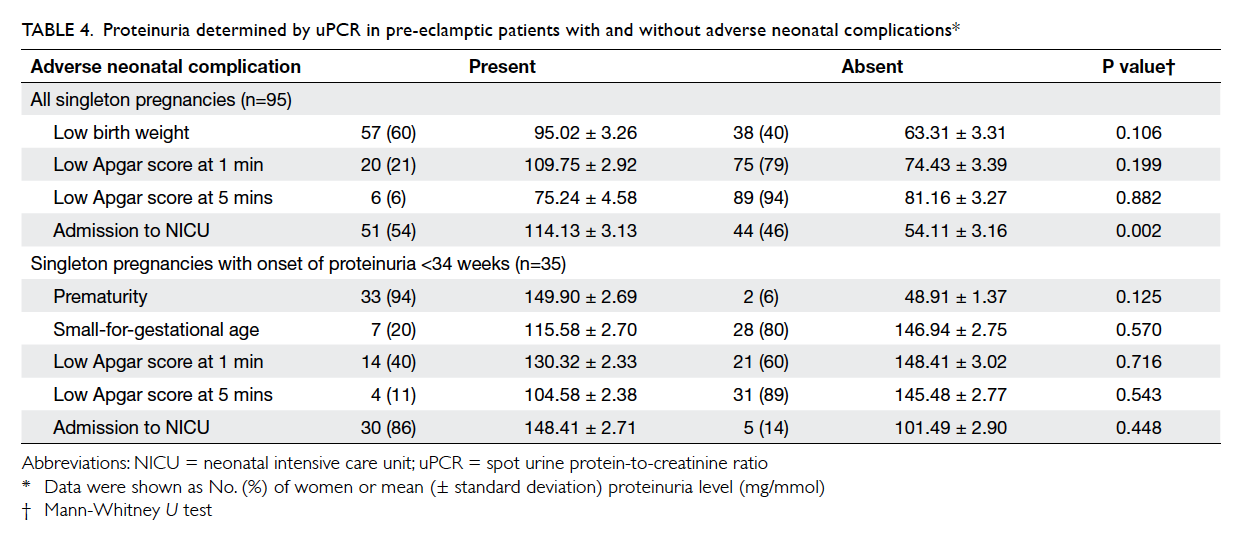

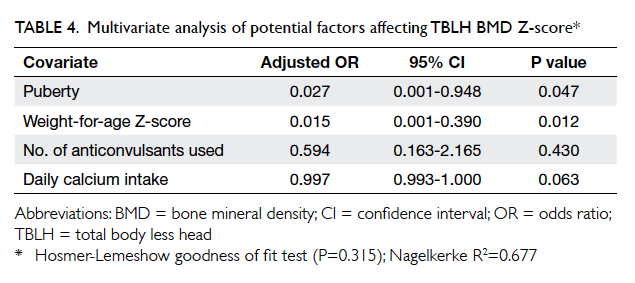

The clinical information of the seven amnesic

MCI subjects are summarised in Table 4. None of the

three subjects without imaging risk factors for AD

deteriorated over a follow-up period of 1 to 5 years.

Of the four amnesic MCI subjects with imaging risk

factors, two deteriorated into AD over a follow-up

period of 5 years.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that 18F-FDG with or

without 11C-PIB PET clarified and improved the

accuracy of dementia diagnosis in 36.3% of patients,

and confirmed the initial diagnosis in 63.7%. Using

the results of PET scan as the gold standard, the

accuracy of clinical diagnosis was low for FTD, VaD,

and mixed dementia collectively. On the one hand,

11.7% of patients (ie 12 out of 102) were started on

symptomatic AD therapy after the 18F-FDG with or

without 11C-PIB PET neuroimaging investigations.

On the other hand, 13.7% of patients (ie 14 out of

102) discontinued symptomatic AD therapy after

18F-FDG with or without 11C-PIB PET because they

did not have AD.

We also showed that the accuracy of clinical

diagnosis of DLB and FTD was low (44.4% and 14.3%,

respectively). This finding was in agreement with a

previous study.20 Both DLB and FTD are commonly

misdiagnosed clinically as AD (50% for DLB and

85.7% for FTD).20 We have previously reported that

100% of our patients with biomarkers that confirmed

DLB and FTD presented with memory impairment

in our memory clinic.20 A previous study also

reported that 26% of DLB patients were initially

misdiagnosed with AD, and 57% of these DLB

patients presented with memory impairment.21 We

understand that an accurate diagnosis of DLB is very

important for subsequent management. Patients

with DLB are particularly sensitive to neuroleptics.21

Neuroleptic sensitivity can present as drowsiness,

confusion, abrupt worsening of parkinsonism,

postural hypotension, or neuroleptic malignant

syndrome.21 Other clinical features of DLB that need

to be observed and tackled include well-formed

visual hallucinations, rapid eye movement sleep

behavioural disorder, and autonomic symptoms

(including postural hypotension, sialorrhoea, and

urinary and bowel symptoms).21 By accurately

establishing the diagnosis of DLB, careful

observation of classic DLB symptoms may reduce

unnecessary investigations. Regarding therapeutic

implications, DLB is characterised by far greater

cholinergic deficits than AD. Hence, most DLB

patients will benefit from ChEIs, and the extent of

symptomatic improvement should be monitored

after such therapy.22

Similarly, FTD may be misdiagnosed as AD.

The former can also present initially with memory

impairment, as illustrated by our FTD patients.

There is increasing evidence that elderly patients

with FTD often present with memory impairment.5 23 24

In one autopsy study, 64% (n=7) of 11 elderly

patients with FTD had anterograde memory loss.23

Current treatment guidelines do not advise giving

ChEIs or memantine treatments to FTD patients.

Thus, such medications should be stopped to prevent

unnecessary adverse effects.25

In the past few years, disease-modifying

treatments (eg bapineuzumab) have failed to

demonstrate their efficacy in clinical trials with

AD patients.26 Detailed post-hoc analyses with AD

biomarkers have shown the problem of diagnosing

AD in subjects recruited in these studies. Only

approximately 80% of these subjects had AD amyloid

pathology, according to the presence of amyloid

PET scan.26 Thus, including 11C-PIB PET to confirm

brain amyloid in study inclusion criteria can help

ensure recruitment of genuine AD patients to future

clinical trials of disease-modifying treatments for

AD.27 Given the minimally invasive nature of 11C-PIB

PET compared with CSF amyloid-beta (Aβ) 42 measurements,7 it is likely to be a more acceptable choice for patients in clinical trials. At present,

there are ongoing clinical trials of AD treatments

including secretase inhibitors, Aβ aggregation

inhibitors, Aβ and tau immunotherapy.27 We believe

that 11C-PIB PET will play an important role in these

clinical trials.

It is considered that 18F-FDG and 11C-PIB PET

may detect underlying AD in patients with MCI.28 In

the present study, 50% of MCI patients (ie 2 out of

4) with 18F-FDG and 11C-PIB PET imaging findings

positive for AD showed deterioration over a follow-up period of 5

years. Although recommending PET brain imaging

in MCI patients is still debatable, we believe that this

investigation can help clinicians to better plan future

and long-term treatments. In particular, disease-modifying

drugs for AD or MCI due to AD may

prove to be effective in the coming decade. Finally,

in the present study, five patients were diagnosed

with unclassifiable dementia. In the four patients

with an AD pattern of hypometabolism, AD may

still be present as they may have diffuse plaques

or amorphous plaques that do not bind well to

PIB. Alternatively they may have another type of

dementia that requires pathological confirmation,

eg argyrophilic grain disease or neurofibrillary

tangle–only dementia.29 We will follow up the

remaining patient with isolated hypometabolism in

the temporal lobes to see whether additional FTD

features develop.

There were several limitations to the present

study. This was a retrospective case series and as

such we were unable to collect further information

such as the pre-imaging or post-imaging confidence

of diagnosis. The diagnosis of dementia relied on

the clinical diagnostic criteria without pathological

confirmation. Therefore, we were also unable to

compare the relative accuracy of clinical diagnosis

and PET diagnosis with pathological diagnosis. For

patients with MCI, some were not followed up for

sufficiently long to ascertain whether or not they had

deteriorated and developed dementia. Structural

imaging (including computed tomography or

magnetic resonance imaging) of the brain was not

analysed as a separate variable but integrated into the

pre-functional imaging clinical diagnoses of dementia

subtypes. Our case series is likely to have selection

bias as PET imaging is mostly a self-paid service in

Hong Kong. The exception is for patients who are

retired civil servants or recipients of Comprehensive

Social Security Assistance. Demented patients who

could not afford PET may differ to the patients

selected. Although the PET images were analysed

and read by radiologists experienced in PET, the

interpretations depended heavily on individual

experience and training; also, radiologists were not

blinded to clinical information written on the request

form. Despite these limitations, our study should be

more reflective of day-to-day practice in a memory

clinic and how 18F-FDG with or without11C-PIB PET

imaging may assist clinical diagnosis.

Conclusions

In this study, 18F-FDG with or without 11C-PIB brain

imaging improved the accuracy of diagnosis of

dementia subtype in 36% of patients with underlying

AD, DLB, VaD, and FTD who presented to our

memory clinic.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Alzheimer’s Disease International World Alzheimer Report 2015: executive summary. Available from: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015-sheet.pdf. Accessed Sep 2015.

2. Lam LC, Tam CW, Lui VW, et al. Prevalence of very mild

and mild dementia in community-dwelling older Chinese

people in Hong Kong. Int Psychogeriatr 2008;20:135-48. Crossref

3. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The

diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease:

recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic

guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement

2011;7:263-9. Crossref

4. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and

management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report

of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2005;65:1863-72. Crossref

5. Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of

revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of

frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011;134:2456-77. Crossref

6. Harris JM, Gall C, Thompson JC, et al. Classification and

pathology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology

2013;81:1832-9. Crossref

7. Shea YF, Chu LW, Zhou L, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid

biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in Chinese patients:

a pilot study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen

2013;28:769-75. Crossref

8. Duits FH, Teunissen CE, Bouwman FH, et al. The

cerebrospinal fluid “Alzheimer profile”: easily said, but

what does it mean? Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:713-723.e2. Crossref

9. Sinha N, Firbank M, O’Brien JT. Biomarkers in dementia

with Lewy bodies: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

2012;27:443-53. Crossref

10. Harris JM, Gall C, Thompson JC, et al. Sensitivity and

specificity of FTDC criteria for behavioral variant

frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2013;80:1881-7. Crossref

11. Davison CM, O’Brien JT. A comparison of FDG-PET and

blood flow SPECT in the diagnosis of neurodegenerative

dementias: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

2014;29:551-61. Crossref

12. Schöll M, Damián A, Engler H. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET in

neurology and psychiatry. PET Clin 2014;9:371-90. Crossref

13. Vandenberghe R, Adamczuk K, Dupont P, Laere KV,

Chételat G. Amyloid PET in clinical practice: Its place

in the multidimensional space of Alzheimer’s disease.

Neuroimage Clin 2013;2:497-511. Crossref

14. Cummings JL. Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease drug

development. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:e13-44. Crossref

15. Ossenkoppele R, Prins ND, Pijnenburg YA, et al. Impact of

molecular imaging on the diagnostic process in a memory

clinic. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:414-21. Crossref

16. Laforce R Jr, Buteau JP, Paquet N, Verret L, Houde

M, Bouchard RW. The value of PET in mild cognitive

impairment, typical and atypical/unclear dementias: A

retrospective memory clinic study. Am J Alzheimers Dis

Other Demen 2010;25:324-32. Crossref

17. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price

D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease:

report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the

auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task

Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939-44. Crossref

18. Román GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular

dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report

of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology

1993;43:250-60. Crossref

19. Waldö ML. The frontotemporal dementias. Psychiatr Clin

North Am 2015;38:193-209. Crossref

20. Shea YF, Ha J, Chu LW. Comparisons of clinical symptoms

in biomarker-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease, dementia

with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal dementia patients

in a local memory clinic. Psychogeriatrics 2014;15:235-41. Crossref

21. Zweig YR, Galvin JE. Lewy body dementia: the impact on

patients and caregivers. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014;6:21. Crossref

22. Gauthier S. Pharmacotherapy of Parkinson disease

dementia and Lewy body dementia. Front Neurol Neurosci

2009;24:135-9. Crossref

23. Baborie A, Griffiths TD, Jaros E, et al. Frontotemporal

dementia in elderly individuals. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1052-60. Crossref

24. Hornberger M, Piguet O. Episodic memory in

frontotemporal dementia: a critical review. Brain

2012;135:678-92. Crossref

25. Portugal Mda G, Marinho V, Laks J. Pharmacological

treatment of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: systematic

review. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2011;33:81-90. Crossref

26. Blennow K, Mattsson N, Schöll M, Hansson O, Zetterberg

H. Amyloid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends

Pharmacol Sci 2015;36:297-309. Crossref

27. Wisniewski T, Goñi F. Immunotherapeutic approaches for

Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2015;85:1162-76. Crossref

28. Langa KM, Levine DA. The diagnosis and management

of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review. JAMA

2014;312:2551-61. Crossref

29. Kovacs GG. Tauopathies. In: Kovacs GG, editor.

Neuropathology of neurodegenerative diseases: a practical

guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;

2015: 125-8.