Corticosteroid adulteration in proprietary Chinese medicines: a recurring problem

Hong Kong Med J 2015 Oct;21(5):411–6 | Epub 28 Aug 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154542

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Corticosteroid adulteration in proprietary Chinese medicines: a recurring problem

YK Chong, MB, BS;

CK Ching, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology);

SW Ng, MPhil;

Tony WL Mak, FRCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)

Hospital Authority Toxicology Reference Laboratory, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Tony WL Mak (makwl@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate adulteration of

proprietary Chinese medicines with corticosteroids

in Hong Kong.

Design: Case series with cross-sectional analysis.

Setting: A tertiary clinical toxicology laboratory in

Hong Kong.

Patients: All patients using proprietary Chinese

medicines adulterated with corticosteroids and

referred to the authors’ centre from 1 January 2008

to 31 December 2012.

Main outcome measures: Patients’ demographic

data, clinical presentation, medical history, drug

history, laboratory investigations, and analytical

findings of the proprietary Chinese medicines were

analysed.

Results: The records of 61 patients who consumed

corticosteroid-adulterated proprietary Chinese

medicines were reviewed. The most common

corticosteroid implicated was dexamethasone. Co-adulterants

such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs and histamine H1-receptor antagonists were

detected in the proprietary Chinese medicine

specimens. Among the patients, seven (11.5%)

required intensive care, two (3.3%) died within 30

days of presentation, and 38 (62.3%) had one or more

complications that were potentially attributable to

exogenous corticosteroids. Of 22 (36.1%) patients

who had provocative adrenal function testing

performed, 17 (77.3% of those tested) had adrenal

insufficiency.

Conclusion: The present case series is the largest

series of patients taking proprietary Chinese

medicines adulterated with corticosteroids.

Patients taking these illicit products are at risk of

severe adverse effects, including potentially fatal

complications. Adrenal insufficiency was very

common in this series of patients. Assessment

of adrenal function in these patients, however,

has been inadequate and routine rather than

discretionary testing of adrenal function is indicated

in this group of patients. The continuing emergence

of proprietary Chinese medicines adulterated with

western medication indicates a persistent threat to

public health.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Adulteration of proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs) with corticosteroids is a significant yet underrecognised phenomenon. Co-adulteration with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and histamine H1-receptor antagonists is often seen.

- Adrenal insufficiency is a common complication in patients who have consumed pCMs adulterated with corticosteroids.

- Adrenal function testing is essential for patients suspected to have taken corticosteroid-adulterated pCMs.

- Public health education on the danger of taking pCMs of dubious sources and implementation of effective regulatory measures are important to address the problem of corticosteroid-adulterated pCMs.

Introduction

Proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs) are products

claimed to be made of Chinese medicines and

formulated in a finished dosage form. As with

traditional Chinese medicine, pCMs are generally

regarded by the public as benign and non-toxic, as

compared with western medications.

Undeclared corticosteroids, among other

adulterants, have been reported to be added to

pCMs, Ayurvedic medicine, and homeopathic

medicine.1 2 3 4 5 There are multiple incentives for adding

corticosteroids: they have powerful analgesic and

anti-inflammatory actions, making these proprietary

products effective against various allergic,

autoimmune, dermatological, and musculoskeletal

pain disorders.

From 2008 to 2012, the Hospital Authority

Toxicology Reference Laboratory, the only tertiary

referral centre for clinical toxicological analysis in

Hong Kong, confirmed 61 cases of corticosteroid-adulterated

pCMs. We report these cases to highlight

the severity and danger of using such adulterated

medications.

Methods

From 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2012, all

cases referred to the Hospital Authority Toxicology

Reference Laboratory that involved the use of

pCMs, which were subsequently found to contain

corticosteroids, were retrospectively reviewed.

Clinical data were obtained by reviewing the

laboratory database as well as the patients’ electronic

and, where necessary, paper health records.

Demographic data, clinical presentation, medical

history, drug history, laboratory investigations,

radiological investigations, and analytical findings

of the pCMs were reviewed. For the evaluation of

adrenocortical function, due to the heterogeneity

of patient population and the nature of the

retrospective case series for the present study, both

low-dose short synacthen test (LDSST) and short

synacthen test (SST) have been used for the diagnosis

of adrenal insufficiency. We adopted a cutoff of

550 nmol/L, which has been traditionally used for

SST, and previously validated in the local population

for LDSST.6

The presumed causal relationship between

the clinical features or complications or both of the

patients and the adulterants was evaluated based on

the temporal sequence, the known adverse effects of

the detected drugs, and the presence of underlying

diseases.

The presence of corticosteroids was analysed

qualitatively by liquid chromatography–tandem

mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with a linear

ion trap instrument. The presence of other co-adulterants

was analysed qualitatively by high-performance

liquid chromatography with diode-array

detection. Confirmations by LC-MS/MS or

gas chromatography–mass spectrometry were

performed as required.

This study was approved by the Hong Kong

Hospital Authority Kowloon West Cluster Research

Ethics Committee (approval number KW/EX-13-121). The Committee exempted the study group from

obtaining patient consent because the presented

data were anonymised, and the risk of identification was

low.

Results

A total of 61 patients involving the use of 61

corticosteroid-adulterated pCMs were referred

to the Hospital Authority Toxicology Reference

Laboratory in Hong Kong. There were 30 men and 31

women, with an age range of 1 to 91 years (median,

65 years). Seven (11.5%) patients were younger than

18 years. The usage duration ranged from 3 days to

10 years, with a median of 4 months.

Most (n=47, 77.0%) patients obtained the corticosteroid-adulterated

pCMs over-the-counter and 13 (21.3%) obtained the

steroid-adulterated pCMs from Chinese medicine

practitioners. The source for one case remained

unknown. Among the 47 patients who obtained their

pCMs over-the-counter, 38 (80.9%) obtained the pCMs in the Mainland China, seven

(14.9%) obtained the pCMs in Hong Kong,

and the remaining two patients (each accounting for

2.1%) obtained the pCMs from Taiwan and Malaysia.

For patients who obtained their pCMs from

Chinese medicine practitioners (n=13), the practitioners

were located in Hong Kong in nine (69.2%),

Mainland China in two (15.4%), and Macau in

two (15.4%) cases.

The three most common indications for the

use of pCMs were musculoskeletal pain (n=36;

59.0%), skin disorders such as eczema and psoriasis

(n=13; 21.3%), and airway problems such as asthma,

bronchiectasis, and chronic obstructive airway

disease (n=8; 13.1%). The indications for all seven

(11.5%) paediatric patients were for skin disorders.

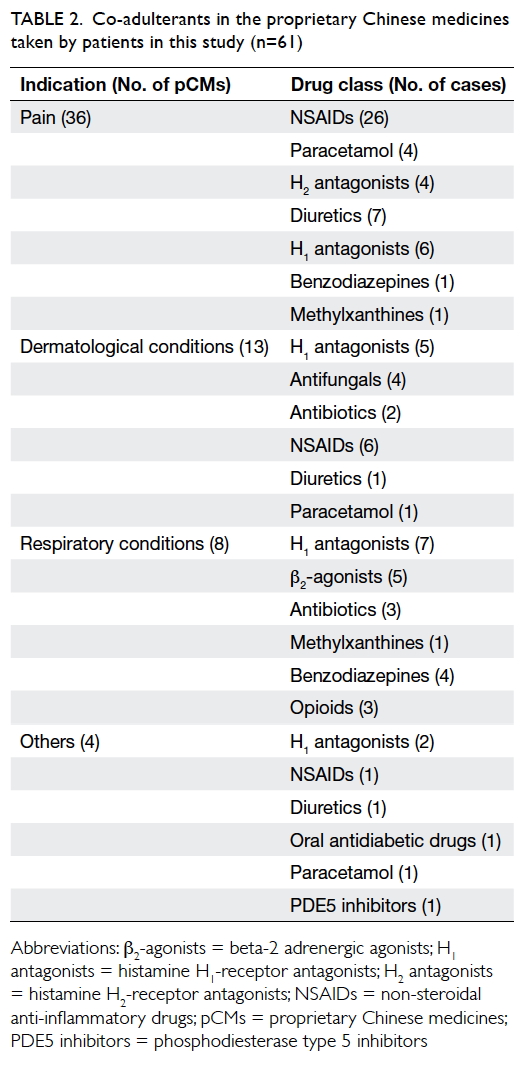

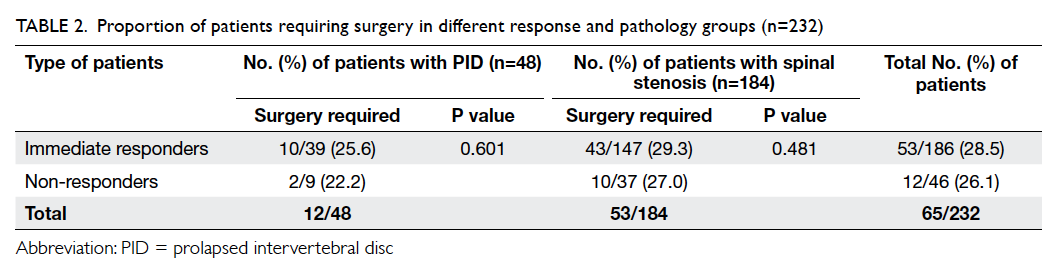

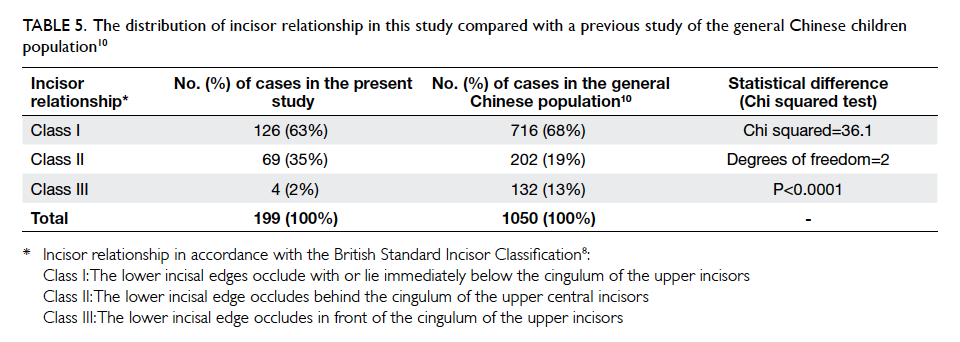

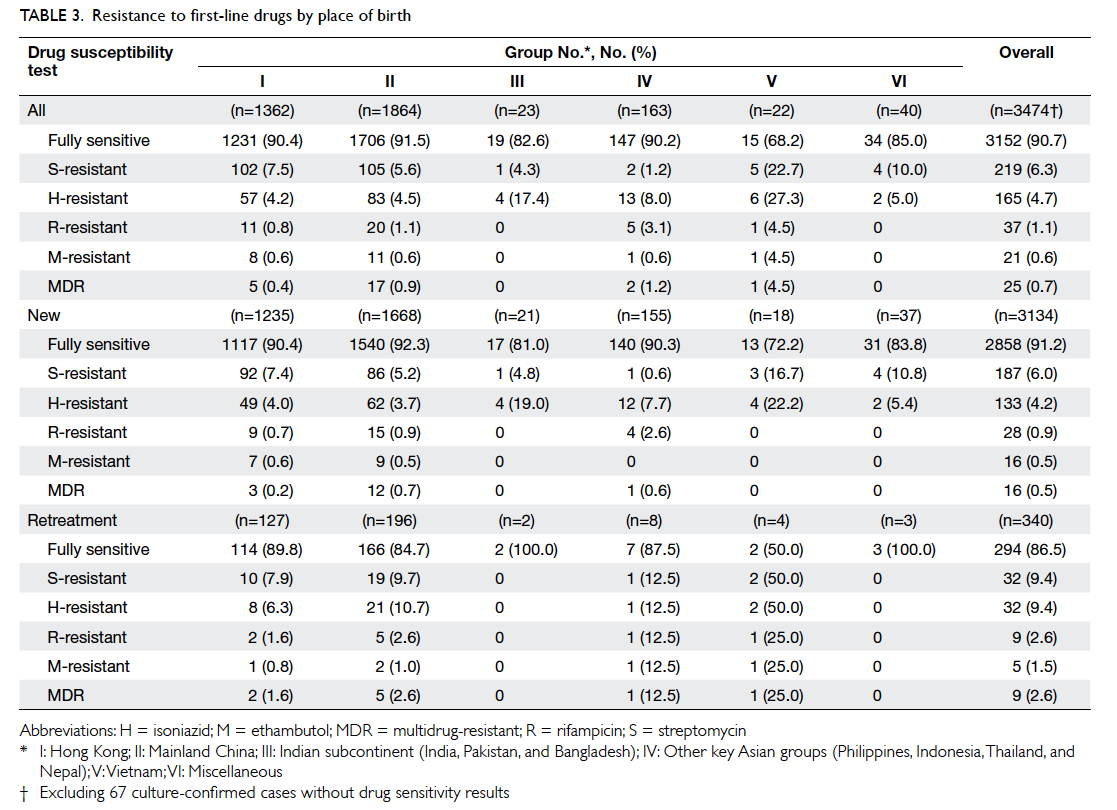

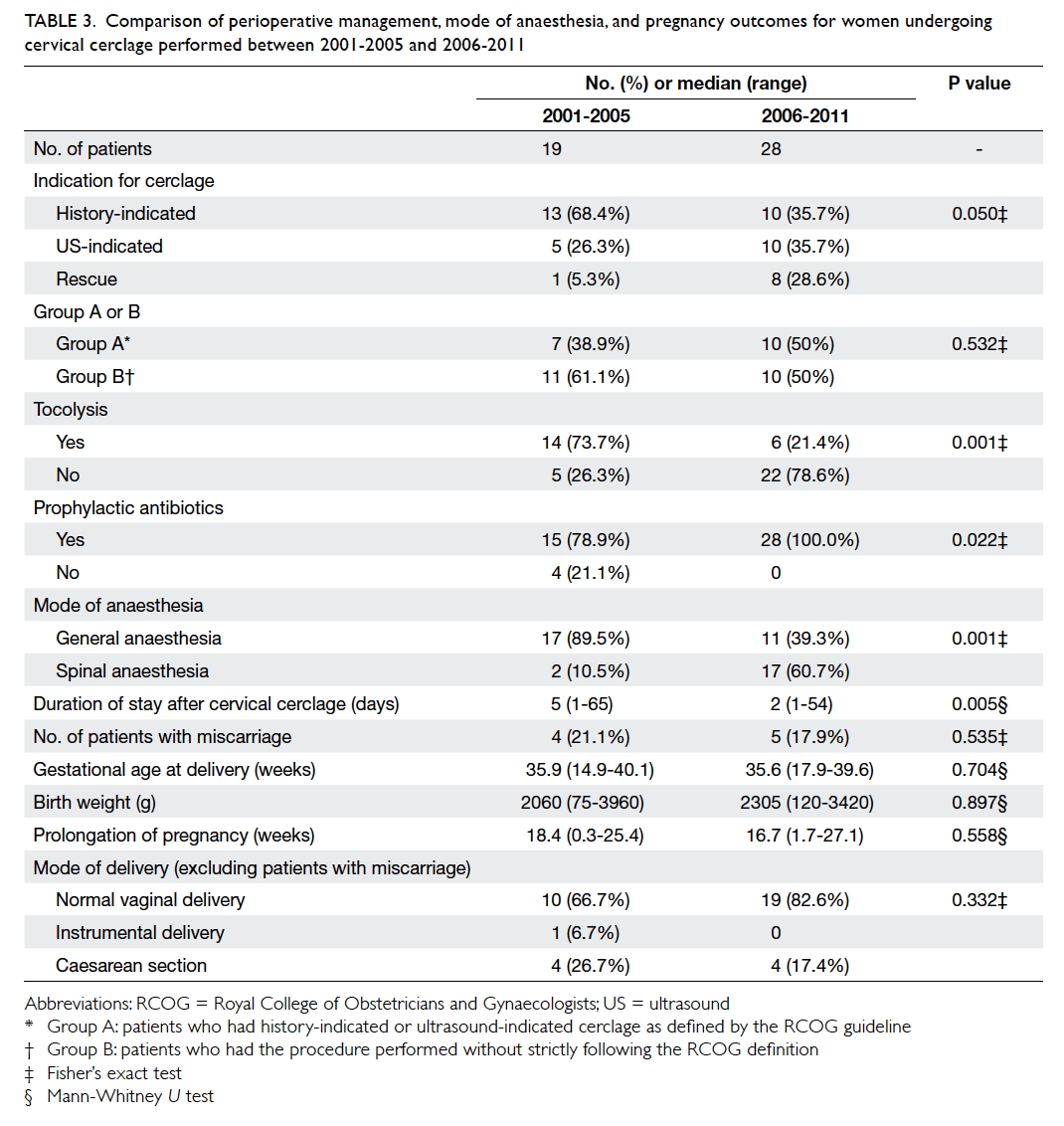

Dexamethasone, present in 29 (47.5%) pCMs,

and prednisone, present in 21 (34.4%) pCMs, were

the most common corticosteroid adulterants among

the pCMs submitted for analysis. Details of the

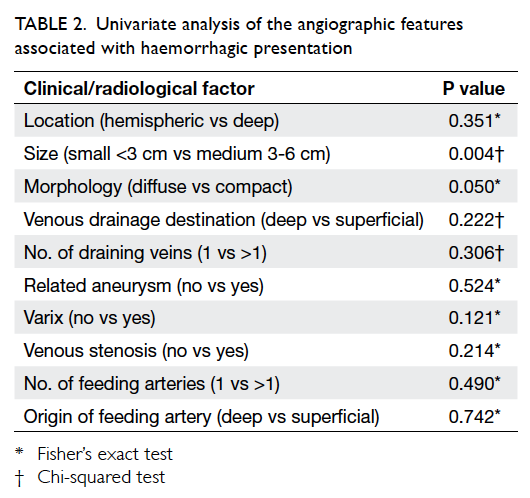

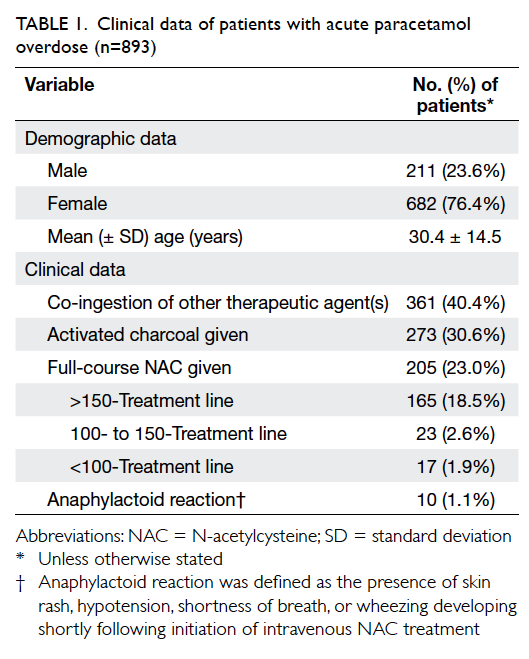

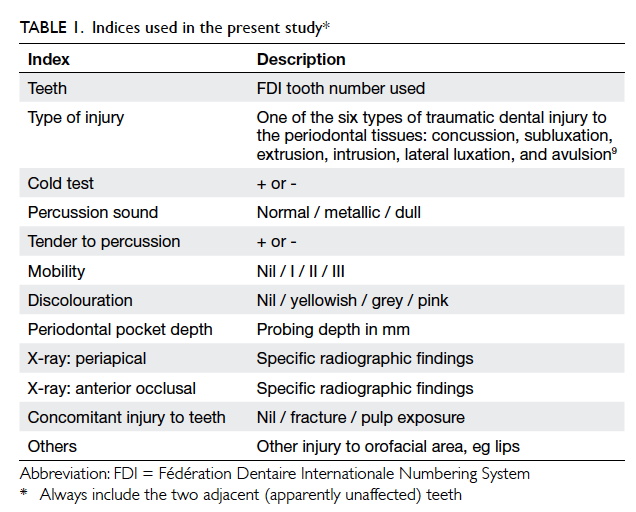

corticosteroid adulteration are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Corticosteroids used to adulterate the proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs) taken by patients in this study (n=61)

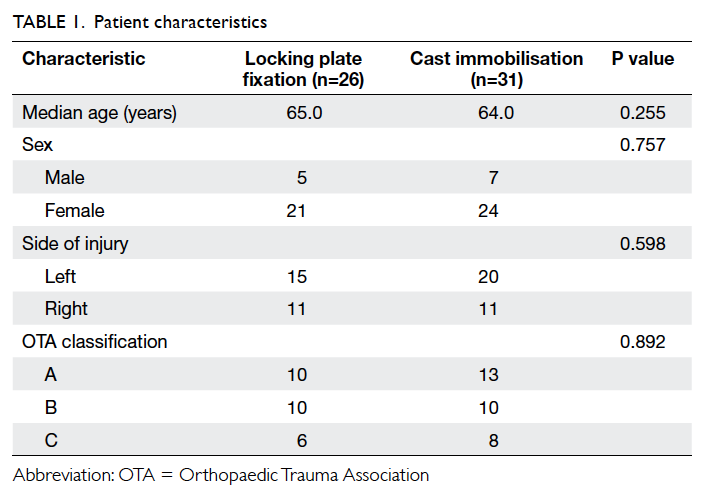

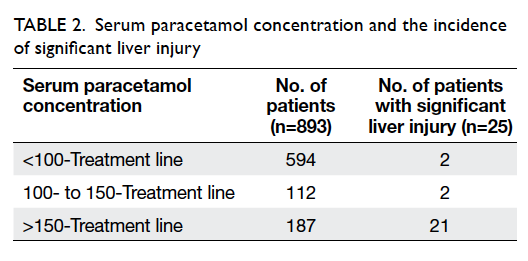

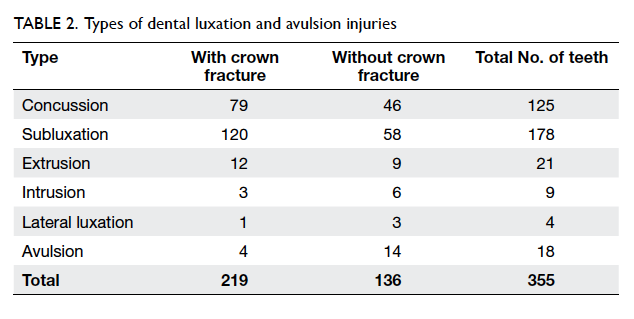

Other than steroids, co-adulterants were also

detected in 53 (86.9%) pCMs. The most common co-adulterants

were non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs; present in 33 [54.1%] pCMs) and

histamine H1-receptor antagonists (present in 20

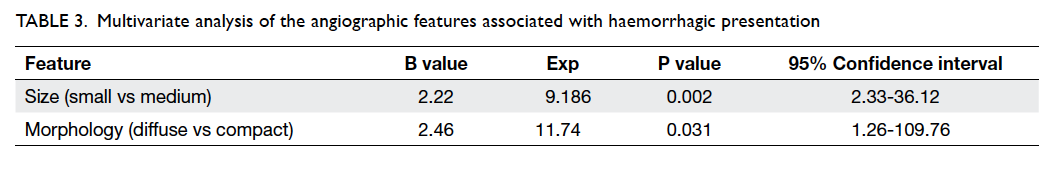

[32.8%] pCMs). The co-adulterants are listed in Table 2.

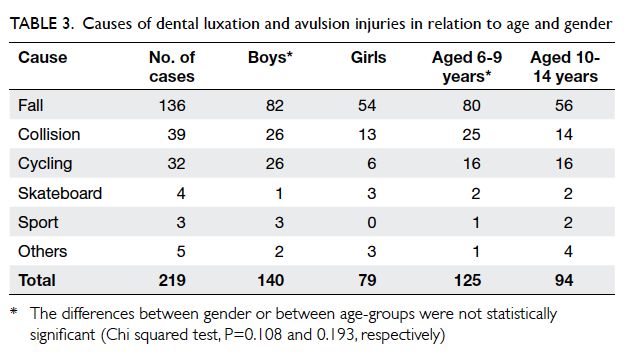

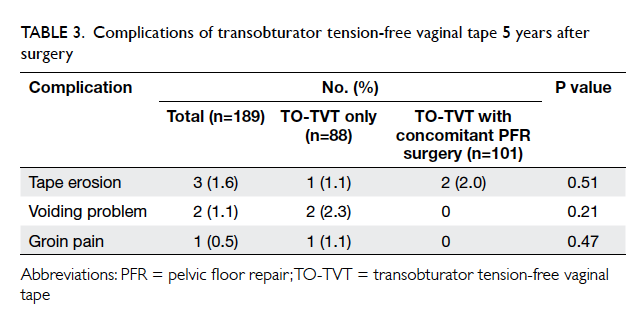

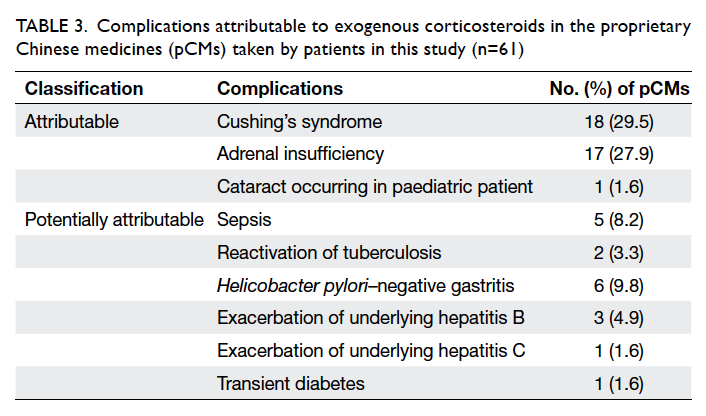

Overall, 38 (62.3%) patients had one or more

complications that were either attributable or

potentially attributable to the use of exogenous

corticosteroids: 18 (29.5%) were documented to

have clinical Cushing’s syndrome; eight (13.1%) had

endoscopic-proven gastritis or peptic ulcer disease,

of whom six (9.8%) were proven to be Helicobacter

pylori–negative; five (8.2%) had sepsis at presentation;

three (4.9%) had hepatitis B exacerbation; and two

(3.3%) had tuberculosis. Other clinical presentations

included hepatitis C reactivation, transient diabetes

that resolved after discontinuation of corticosteroids,

and cataract occurring in a paediatric patient.

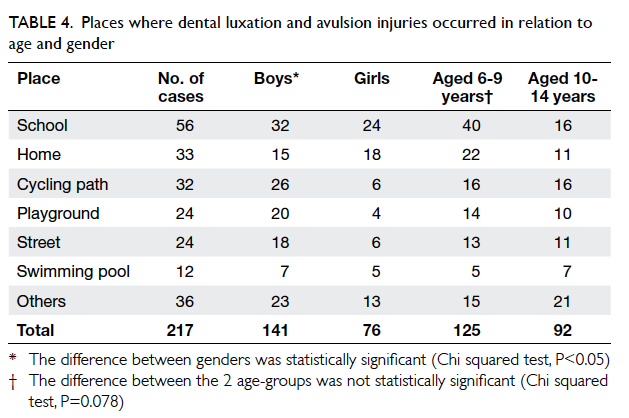

Overall, 22 (36.1%) patients had adrenal function

testing performed, and among them 17 (77.3%) had

biochemically confirmed adrenal insufficiency.

For the subgroup in whom Cushing’s

syndrome was not identified (n=43; 70.5%), LDSST/SST were performed in 11 (25.6%), and among those,

seven (63.6%) had biochemically confirmed adrenal

insufficiency.

Seven (11.5%) patients in this series required

intensive care, and two (3.3%) died within 1 month

of initial presentation. Among the patients who had

consumed pCMs adulterated with corticosteroids

and required intensive care unit admission, the

clinical presentations of two patients may have been

related to the use of corticosteroids, which are described below.

Case 1

The patient was a 67-year-old man who had a

history of psoriasis, diabetes, hypertension, and

chronic renal impairment. He presented in 2012

with fever, decreased urine output, and gastro-intestinal

upset. He reported a 2-month history of

using a pCM for psoriasis, and his skin condition

dramatically improved. He was in shock on

admission, with acute renal failure and respiratory

distress. He was admitted to the intensive care unit

where he stayed for 7 days. He required inotropic

support and mechanical ventilation. Computed

tomography revealed a large lung abscess and blood

culture showed Pseudomonas species. During his

hospitalisation, SST was performed, and the results

were adequate (cortisol level of 944 nmol/L at 30 minutes

after synacthen injection).

In the pCM submitted for analysis, prednisone

acetate was detected, among other herbal markers.

His condition improved with drainage of the abscess

and prolonged intravenous antibiotics, including

cefoperazone and sulbactam (1 g and later 2 g every

12 hours intravenously [IV] for 39 days) as well as

imipenem and cilastatin (500 mg every 8 hours

IV for 51 days). He was discharged after a long

rehabilitation programme, 3 months after the initial

admission.

Case 2

The patient was a 61-year-old man. He presented

in 2009 with a history of asthma, and was a chronic

smoker. He initially presented with low back pain

after slipping and falling. He, however, was noted to

have bilateral apical opacities on chest radiograph,

and was found to have smear-positive, open

pulmonary tuberculosis.

He was put on piperacillin (4 g every 6

hours IV), augmentin (1.2 g every 8 hours IV),

clarithromycin (500 mg twice a day orally), isoniazid

(300 mg daily orally), rifampicin (450 mg daily

orally), and ethambutol (700 mg daily orally) initially

while he was intubated, ventilated, and admitted to

intensive care unit for respiratory failure. During

his initial improvement in the intensive care unit,

he reported the use of a kind of herbal powder,

which he took to alleviate his airway condition. In

the herbal powder, opium alkaloids (morphine,

codeine), oxytetracycline, diazepam, clenbuterol,

and prednisone were detected, among other herbal

markers.

His condition later deteriorated and he went

into respiratory failure and required intubation.

Subsequently, he died of ventilator-associated

Escherichia coli pneumonia. In this patient,

adrenal function testing with LDSST/SST was not

performed.

Discussion

Corticosteroids are notorious for causing side-effects

such as Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency,

cataracts, peptic ulcer disease, osteoporosis, and

decreased immune response, particularly when used

for a protracted period of time in high doses. The

latest Endocrine Society guidelines on the diagnosis

of Cushing’s syndrome has also stressed obtaining

a thorough history to exclude excessive exogenous

glucocorticoid exposure leading to iatrogenic

Cushing’s syndrome.7 The continuing emergence

of corticosteroid-adulterated pCMs indicates that

iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome is a persistent

problem with public health implications.

The incentive behind adulteration of pCMs is

easily understandable. Most of the pCMs involved

suggest that they are useful for the treatment of pain,

skin problems, or respiratory ailments. Steroids,

notwithstanding their many adverse effects, are

effective therapy for pain, inflammatory disorders,

allergic skin problems, and respiratory disorders

such as asthma and chronic obstructive airway

disease.

Although the side-effects of corticosteroids

have been extensively described over the past century,

many of these effects are multifactorial in their

pathophysiology, and the effect of corticosteroids

is difficult to quantitate in isolation. For example,

Cushing’s syndrome and adrenal insufficiency as

adverse drug reactions associated with the use of

corticosteroid-adulterated pCMs are less likely to

be disputed, for example H pylori–negative peptic

ulcer disease can be due to stress, alcoholism, use of

NSAIDs, and other concomitant illnesses.

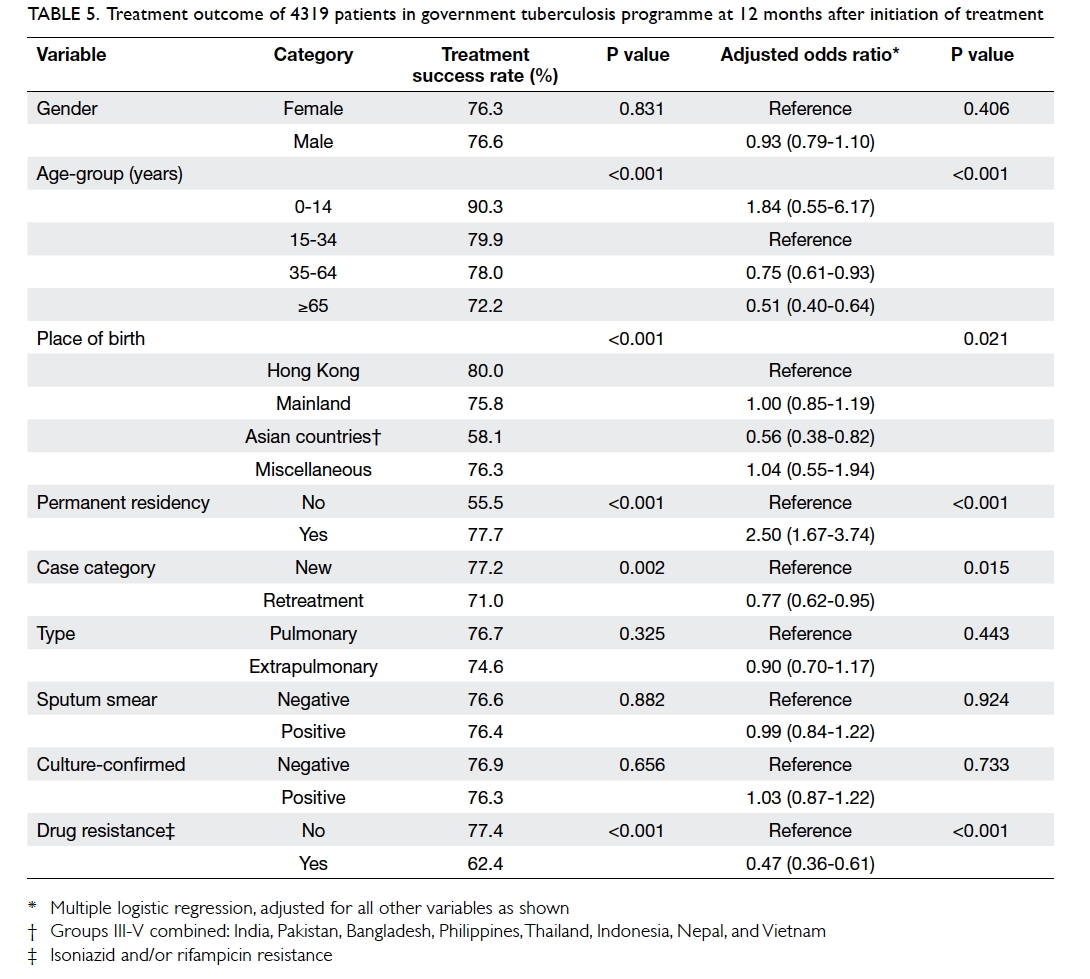

Despite the presence of confounding factors,

the adverse effects of corticosteroid use are suspected

in many of the patients who use corticosteroid-containing

pCMs: for example, the deep-seated

infection in patient 1 and open tuberculosis in patient

2 could well be a result of immunosuppression due to

the use of corticosteroids. For the paediatric patient

with cataract on presentation, given that the patient

had no other clinical features to suggest a metabolic

or exogenous cause for the cataract, it is more likely

that the presence of the cataract was due to the

use of corticosteroids. The authors considered all

cases of Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency,

and cataract occurring in paediatric patients to be

attributable to the use of exogenous steroids. The

prevalence of these conditions in this case series and

other conditions that are potentially attributable to

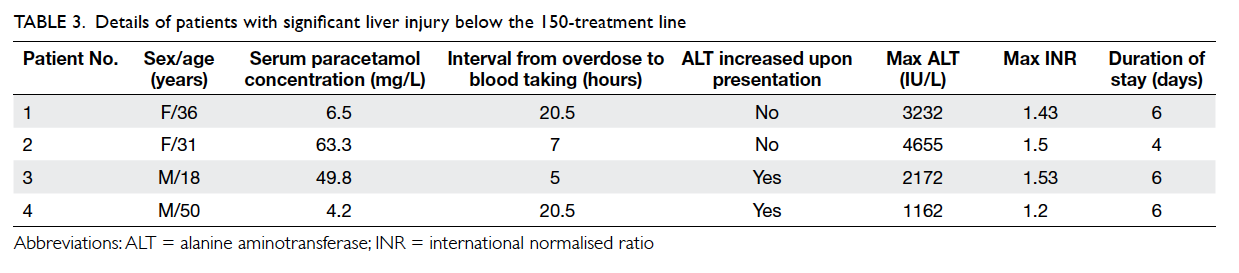

the use of exogenous corticosteroids are listed in

Table 3.

Table 3. Complications attributable to exogenous corticosteroids in the proprietary Chinese medicines (pCMs) taken by patients in this study (n=61)

The presence of co-adulterants in steroid-adulterated

pCMs appears to be the rule rather than

the exception. It cannot be overstressed that co-adulterants

present in pCMs are equally dangerous,

even when compared with corticosteroids, for

example, the presence of multiple NSAIDs

together with steroids puts patients at high risk

for complications (such as acute kidney injury and

peptic ulcer disease), and opiates (such as codeine

and morphine) present in pCMs indicated for

respiratory conditions puts patients, who most likely

have asthma or chronic obstructive airway disease,

at high risk for respiratory depression and carbon

dioxide narcosis. While effective at ameliorating

symptoms, these drugs delay the clinical presentation

and hence the opportunity to treat the disease at an

early stage.

Many therapeutically irrelevant medications

were also found in the pCMs. Examples include

histamine H1-receptor antagonists found in

adulterated pCMs that are intended to treat bone

pain, and the presence of tadalafil (a drug used to

treat erectile dysfunction) found in an adulterated

pCM that is supposed to treat diabetes.

It is difficult to comprehend the reason behind

the addition of such co-adulterants, although

contamination due to poor pharmaceutical

manufacturing practice is likely a contributing

factor, if not the sole reason.

For the diagnosis of exogenous corticosteroid

intake, maintaining a high index of suspicion is of

utmost importance. The classical feature of Cushing’s

syndrome was present in less than 30% of patients in

this series. This indicates that a large proportion of

cases would likely be missed if biochemical testing

was only performed following demonstration of

classical features of exogenous steroid intake. This

experience indicates that it is often worthwhile

testing patients who improve dramatically with the

use of pCMs from dubious sources, especially when

the treatment claims to be effective for treating

pain, airway diseases, and childhood eczema. In

these cases, a detailed drug history, and laboratory

analysis of suspicious pCMs can help to confirm the

diagnosis.

The management of these patients starts with

termination of exposure to the adulterated pCMs,

and treatment of the complications that have already

occurred. It is prudent to provide corticosteroid

replacement therapy pending dynamic function test

for adrenal function. For patients with underlying

inflammatory or autoimmune disorders such as

gouty arthritis, psoriasis, and eczema, abrupt

discontinuation of corticosteroid medications

may trigger an exacerbation of disease. In these

groups of patients, slow, gradual tapering should be

considered.

A worrying observation in the present series

is the occurrence of adrenal insufficiency, as well as

the lack of investigations thereof. Patients who were

exposed to pCMs adulterated with corticosteroids

were clearly at risk of adrenal insufficiency due

to suppression of adrenocorticotropic hormone

secretion and the resultant adrenocortical atrophy.

In this series, LDSST/SST was only performed

in 36.1% of the patients, and in those patients in whom

the tests were performed, 77.3% were inadequate.

It is clear that, among the patients who were not

tested, some were likely to have undiagnosed adrenal

insufficiency. As undiagnosed adrenal insufficiency

carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality, the

authors believe that LDSST should be performed on

all patients who have significant exposure to pCMs

adulterated with corticosteroids, even if they have

no signs of Cushing’s syndrome.

While spot cortisol obtained in the morning

is diagnostic if it is <100 nmol/L or >420 nmol/L

as verified locally by Choi et al,6 we recommend

LDSST as the test for adrenal function; LDSST

(1 µg) is preferred over the standard (250 µg) SST

because studies indicate that LDSST may be more

sensitive in detecting partial adrenal insufficiency.8 9

The authors further recommend that a sensitive

cutoff of 550 nmol/L at 30 minutes be used for the

purpose of diagnosing adrenal insufficiency in this

group of patients. Our recommendation for use of

provocative adrenal testing and a sensitive cutoff

level is based on the high probability of adrenal

insufficiency in this group of patients.

Prevention is always better than cure, and

this is especially true for public health issues. While

analytical and clinical toxicologists are well aware

of the situation, it is important to bring this matter

to the other stakeholders in society, namely, policy-makers, frontline clinicians, and the general public,

with communication tailored to the recipients.

For the general public, a simple rule can be

taught: if it sounds too good to be true, it probably

is; and this is especially so for pCMs that claim to

treat certain conditions in which western-drug

adulteration is common, for example, weight

reduction and diabetes, as previously reported by

our unit,10 11 and pain, respiratory conditions, and

skin problems, as reported in the present study. It

is prudent to consider brands and retailers that are

trustworthy and, in case of doubt, patients should

seek opinion from their primary care doctors.

For frontline clinicians, we wish to bring

to their attention that this adulteration issue is

common, recurring, and worthy of consideration,

and that patients who have a history of using such

corticosteroid-adulterated pCMs should have their

adrenal function tested. It is also important that

iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome subsequent to the

use of corticosteroids that are from a source of

adulteration be reported to the relevant authorities.

It is the opinion of the authors that liberal, but careful,

reporting would contribute to better understanding

of this problem, further the prosecution of those

behind steroid-adulteration of pCMs, and help to

ameliorate this public health problem.

As for legislation and policies, consideration of

fraudulent prescription contrary to the expectation

of patients, who would expect traditional Chinese

medicine rather than the inappropriate use of

corticosteroids seen in many of these cases, by the

legislators, judiciary, and relevant councils and

constituents, rather than focusing on the possession

and unlawful sale of the relevant compounds, would

be a great deterrent to these illicit practices.

Conclusion

The present case series is the largest series of patients

using pCMs adulterated with corticosteroids. The

continuing emergence of pCMs adulterated with

western medications indicates a persistent threat to

public health. It is thus important that the risk be

communicated not only to the medical profession,

but also to the public, and effective regulatory

measures to combat these illicit pCMs should be in

place.

References

1. Ahmed S, Riaz M. Quantitation of cortico-steroids

as common adulterants in local drugs by HPLC. Chromatographia 1991;31:67-70. Crossref

2. Hon KL, Leung TF, Yau HC, Chan T. Paradoxical use of oral

and topical steroids in steroid-phobic patients resorting to

traditional Chinese medicines. World J Pediatr 2012;8:263-7. Crossref

3. Ku Y, Wen K, Ho L, Chang YS. Solid-phase extraction and

high performance liquid chromatographic determination

of steroids adulterated in traditional Chinese medicines. J

Food Drug Anal 1999;7:123-30.

4. Morice A. Adulteration of homoeopathic remedies. Lancet 1987;329:635. Crossref

5. Savaliya AA, Prasad B, Raijada DK, Singh S. Detection and

characterization of synthetic steroidal and non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs in Indian ayurvedic/herbal

products using LC-MS/TOF. Drug Test Anal 2009;1:372-81. Crossref

6. Choi CH, Tiu SC, Shek CC, Choi KL, Chan FK, Kong PS.

Use of the low-dose corticotropin stimulation test for the

diagnosis of secondary adrenocortical insufficiency. Hong

Kong Med J 2002;8:427-34.

7. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis

of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical

Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1526-40. Crossref

8. Broide J, Soferman R, Kivity S, et al. Low-dose

adrenocorticotropin test reveals impaired adrenal function

in patients taking inhaled corticosteroids. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 1995;80:1243-6. Crossref

9. Streeten DH, Anderson GH Jr, Bonaventura MM. The

potential for serious consequences from misinterpreting

normal responses to the rapid adrenocorticotropin test. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:285-90. Crossref

10. Ching CK, Lam YH, Chan AY, Mak TW. Adulteration

of herbal antidiabetic products with undeclared

pharmaceuticals: a case series in Hong Kong. Br J Clin

Pharmacol 2012;73:795-800. Crossref

11. Tang MH, Chen SP, Ng SW, Chan AY, Mak TW. Case

series on a diversity of illicit weight-reducing agents: from

the well known to the unexpected. Br J Clin Pharmacol

2011;71:250-3. Crossref