Amoebic liver abscesses with an unusual source: a case report

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

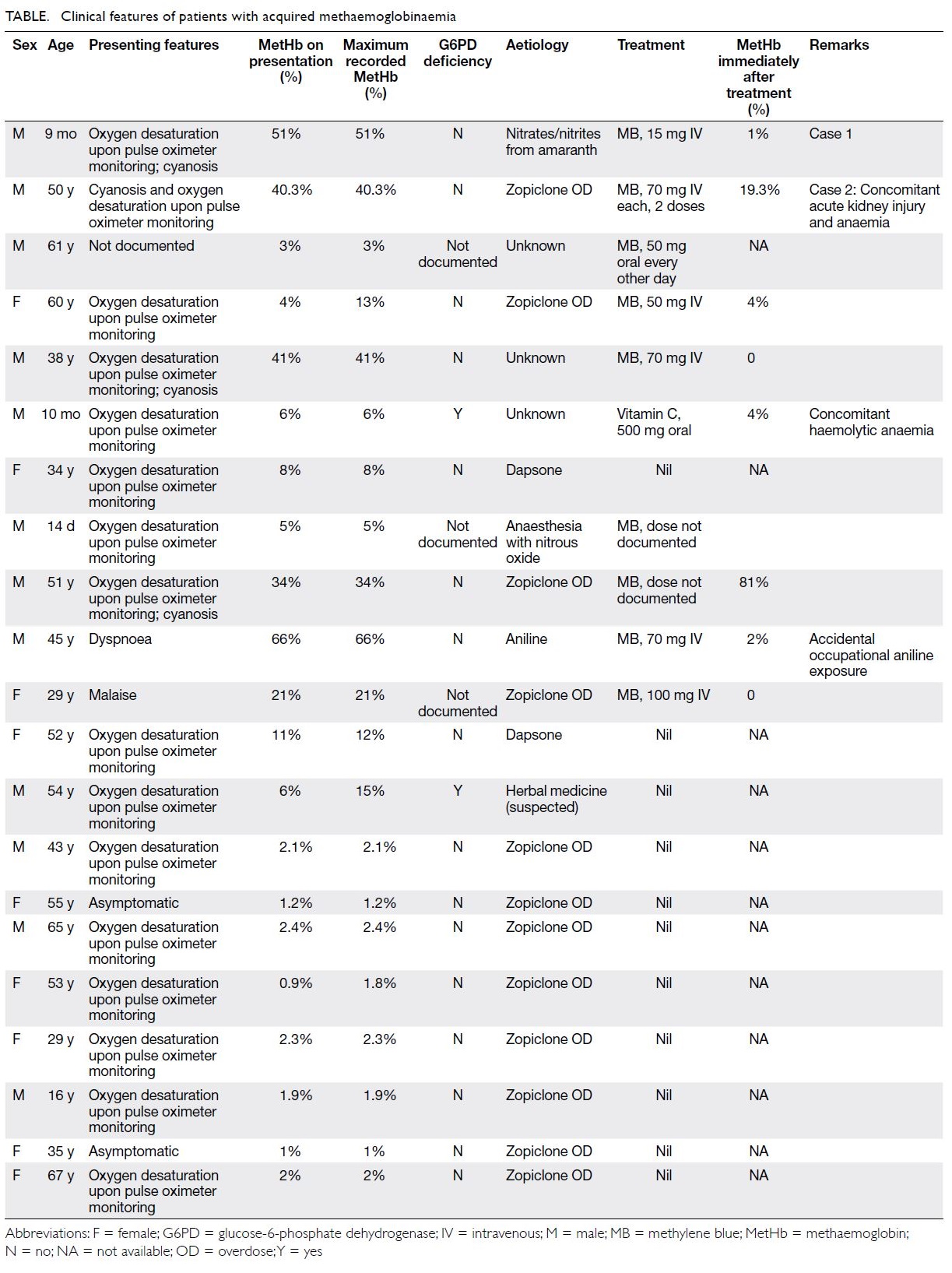

CASE REPORT

Amoebic liver abscesses with an unusual source:

a case report

Juanita N Chui, BSc (Adv), MD1; Albert KK Chui, FRACS, MD2

1 School of Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

2 Private Practice, 12/F, Emperor Commercial Centre, Central, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Albert KK Chui (akkchui@netvigator.com)

Case report

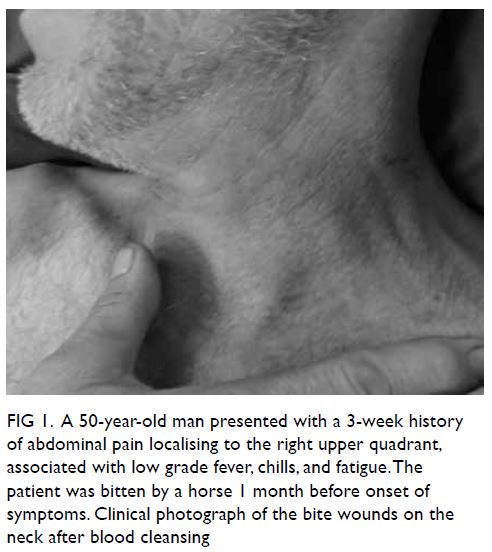

In July 2020, a 50-year-old man presented to a

public hospital in Hong Kong with a 3-week history

of abdominal pain localising to the right upper

quadrant, associated with low-grade fever, chills, and fatigue. He denied any diarrhoea or vomiting.

His medical history and family history were

unremarkable. He was a non-smoker and consumed

alcohol infrequently. He had recently returned from

Southern California, United States, where he was

bitten by a horse 1 month before the onset of his

symptoms. Despite sustaining deep wounds to his

left neck (Fig 1), he did not seek medical attention

at the time.

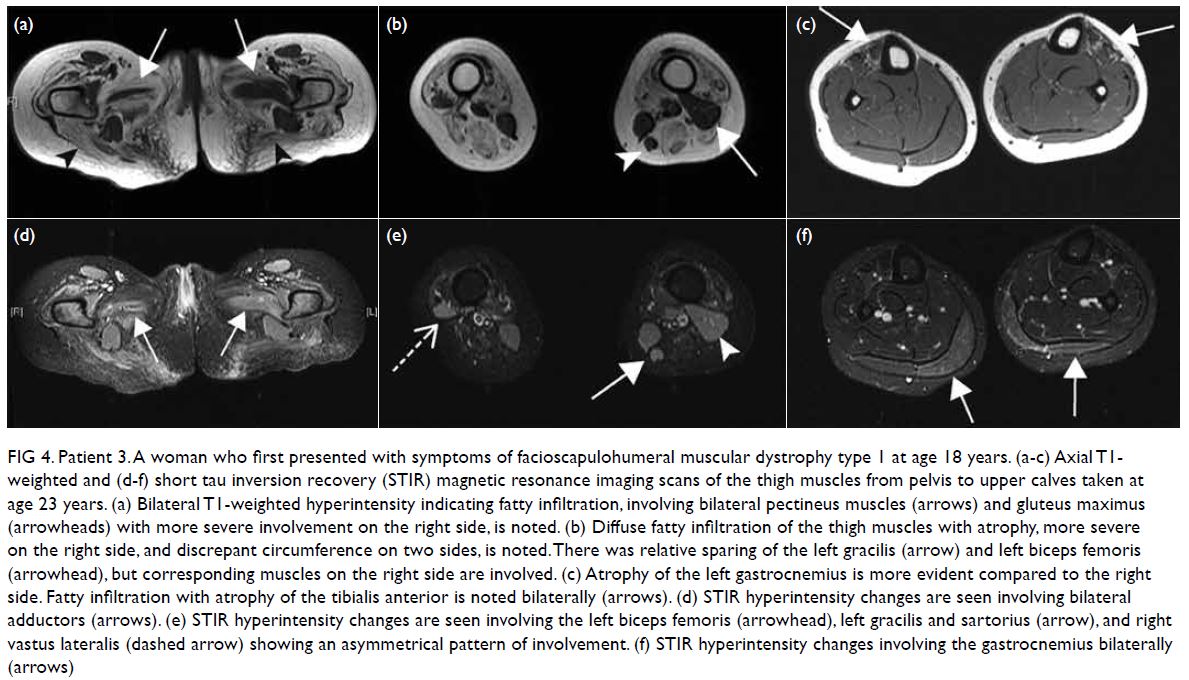

Figure 1. A 50-year-old man presented with a 3-week history of abdominal pain localising to the right upper quadrant, associated with low grade fever, chills, and fatigue. The patient was bitten by a horse 1 month before onset of symptoms. Clinical photograph of the bite wounds on the neck after blood cleansing

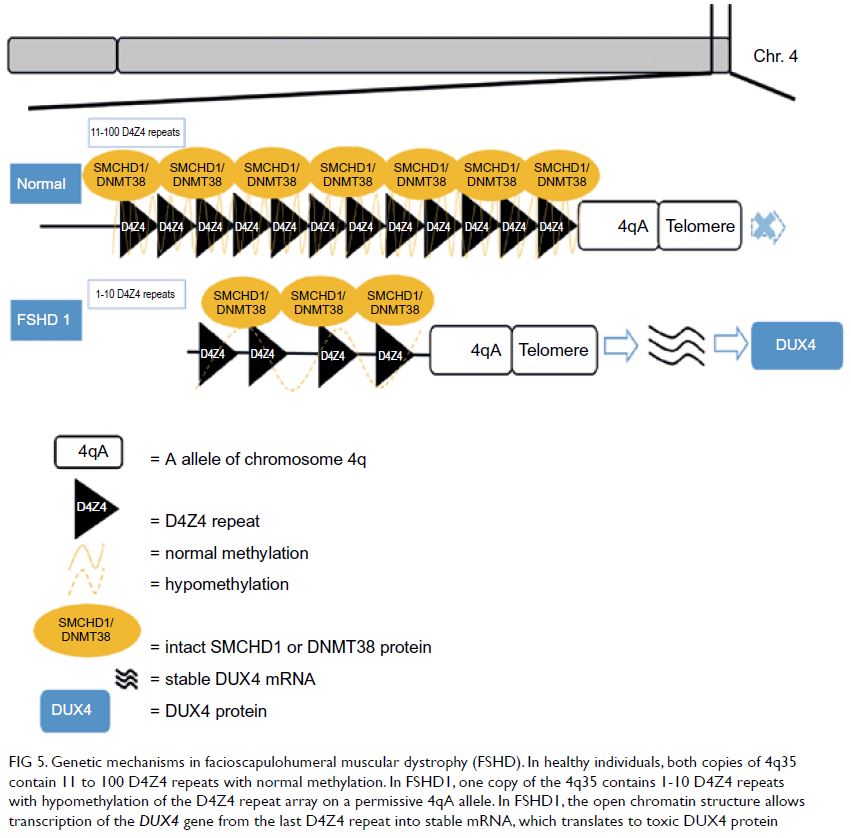

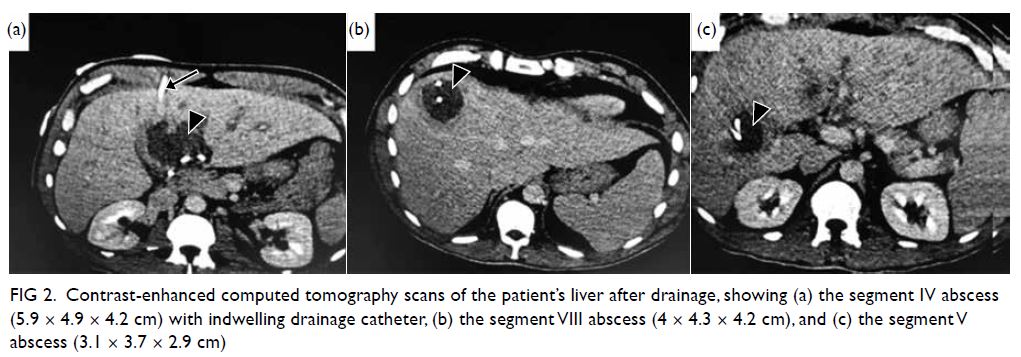

On admission, a contrast-enhanced computed

tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed

three liver abscesses. He was treated initially with

intravenous antibiotic (amoxicillin/clavulanic

acid for 5 days before switching to piperacillin/tazobactam) but his clinical condition showed no

improvement. A new CT scan 5 days later showed

enlargement of the abscesses. Percutaneous drainage

of the abscesses was performed under ultrasound

guidance and the patient was transferred to our

private hospital for further management.

On arrival, the patient was haemodynamically

stable but clinically dehydrated, jaundiced, and

delirious. The abdomen was soft and non-tender,

with three abdominal drainage tubes in situ. A new

CT scan confirmed that the liver abscesses and

the drainage tubes were blocked, and they had to

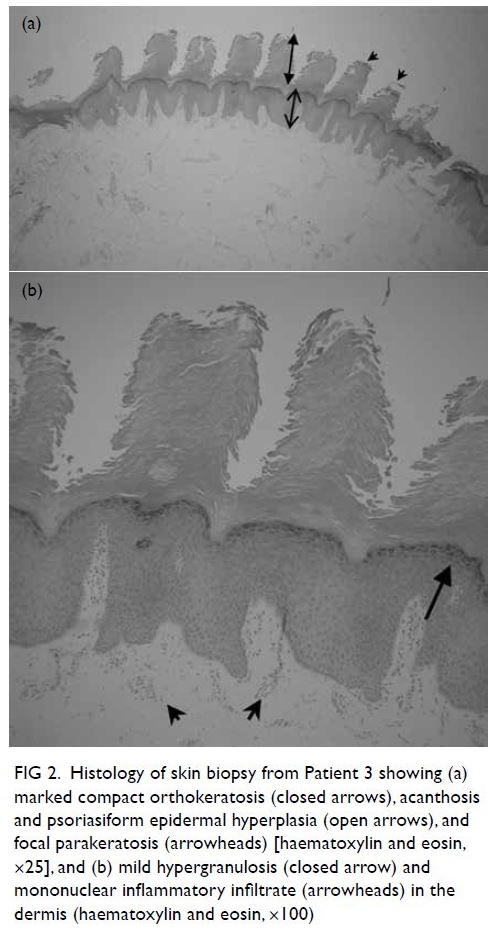

be replaced (Fig 2). Drainage fluid afterwards was

noted to have the appearance of anchovy sauce and

amoebic infection was suspected.

Figure 2. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans of the patient’s liver after drainage, showing (a) the segment IV abscess (5.9 × 4.9 × 4.2 cm) with indwelling drainage catheter, (b) the segment VIII abscess (4 × 4.3 × 4.2 cm), and (c) the segment V abscess (3.1 × 3.7 × 2.9 cm)

Blood tests on arrival showed leucocytosis

(white cell count 31 × 109/L) with markedly elevated

inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein 357 mg/L),

and deranged liver function (alkaline phosphatase

231 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 64 U/L, bilirubin

56 μmol/L and albumin 26.5 g/L). Blood cultures

were negative. No abnormalities were found on

colonoscopy and stool ova, cysts and parasite

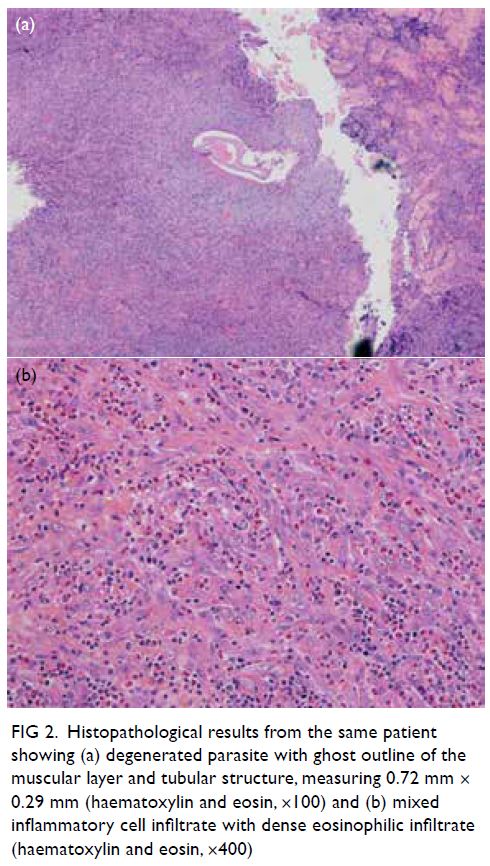

microscopy were negative. Fluid drained from the

abscesses was negative on microscopy and culture,

but positive for Entamoeba histolytica DNA on

polymerase chain reaction. Initial amoebic serology

was negative for E histolytica immunoglobulin G

antibodies. Intravenous metronidazole was

commenced empirically in addition to piperacillin/

tazobactam. The patient subsequently made a steady

recovery. New amoebic serology demonstrated a

significant titre of E histolytica immunoglobulin G

antibodies 9 days later, indicating recent amoebic

infection. Repeated blood tests showed continued

normalisation of initial results and follow-up CT

scans showed progressive resolution of abscesses.

The patient was discharged from the hospital after

2 weeks.

Discussion

Amoebiasis is a leading parasitic infection in terms

of morbidity and mortality worldwide. It is most

prevalent in developing countries and in tropical

regions. It is caused by the protozoa, E histolytica,

transmitted via the faecal-oral route by ingestion

of contaminated food or water containing amoebic

trophozoites or cysts. Acute infection typically

presents as amoebic colitis. The most common

symptoms associated with amoebiasis are abdominal

pain (98% of cases), fever (74%), and dysentery

(30%).1 2 Although extraintestinal complications

of invasive infection are rare (<1% of cases),

liver abscesses are the most common secondary

manifestation, occurring when trophozoites invade

the colonic mucosa and penetrate mesenteric

venules to enter the portal circulation.3

This case was an unusual presentation of

amoebic liver abscess, confirmed by polymerase

chain reaction testing of aspirates and serology

results that suggested an acute infection. However,

the patient presented with no gastrointestinal

symptoms typical of amoebic colitis and stool

investigations and colonoscopy were normal. The

typical period of incubation for amoebiasis in those

with liver abscesses has been reported to be 8 to

20 weeks.4 In this case, the patient presented with

symptoms of invasive disease 4 weeks following

his horse bite. The patient denied recent travel to

an endemic area or any sick contacts. Southern

California is known to have many migrants from

South America where amoeba is prevalent. There

was little evidence from the patient’s clinical history or investigations to support a faecal-oral route of

transmission. As such, the possibility of liver abscess

from a cutaneous source was considered.

The patient was initially treated for pyogenic

liver abscess. Drainage of the abscesses and the

addition of metronidazole dramatically improved

his condition. It is conceivable that the horse bite

harboured amoebic trophozoites or otherwise

facilitated their invasion from contaminated

environmental water, soil, or vegetation. Just as

invasive trophozoites are known to reach the liver

by hematogenous dissemination to form abscesses,

in our patient they may have entered the circulation

via the bite wound to invade the liver. The short

incubation period was also consistent with direct

inoculation. Although cutaneous bacterial infection

leading to liver pyogenic abscesses is well reported

in the literature, the development of amoebic liver

abscesses from a similar source has not previously

been described. This may be the first described case

of amoebic liver abscesses of cutaneous origin and

warrants further study.

Author contributions

Concept or design: AKK Chui.

Acquisition of data: AKK Chui.

Analysis or interpretation of data: AKK Chui.

Drafting of the manuscript: Both authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Both authors.

Acquisition of data: AKK Chui.

Analysis or interpretation of data: AKK Chui.

Drafting of the manuscript: Both authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Both authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the Journal, AKK Chui was not involved in the peer review process for this article. The other author has

disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient consent was obtained.

References

1. Akgün Y, Taçyιlιdιz ÏH, Çelik Y. Amoebic liver abscess: changing trends over 20 years. World J Surg 1999;23:102-6. Crossref

2. Donovon AJ, Yellin AE, Ralls PW. Hepatic abscess. World J Surg 1991;15:162-9. Crossref

3. Swaminathan V, O’Rourke J, Gupta R, Kiire CF. An unusual presentation of an amoebic liver abscess:

the story of an unwanted souvenir. BMJ Case Rep

2013;2013:bcr2012006964. Crossref

4. Li E, Stanley SL Jr. Protozoa. Amebiasis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996;25:471-92. Crossref