© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

secondary to dengue fever: a case report

SW Cheo, MRCP (UK)1; HJ Wong, MRCP (UK)2; EK Ng, MRCP (UK)3; QJ Low, MRCP (UK)4; YK Chia, MRCP (UK)5

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Lahad Datu, Lahad Datu, Sabah, Malaysia

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Duchess of Kent, Sandakan, Sabah, Malaysia

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Tawau, Sabah, Malaysia

4 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Sultanah Nora Ismail, Batu Pahat, Johor, Malaysia

5 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Queen Elizabeth, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia

Corresponding author: Dr SW Cheo (cheosengwee@gmail.com)

Case report

A 15-year-old boy with good past health presented

with a 1-day history of fever, four episodes of vomiting,

and lethargy. He denied diarrhoea, headache, or

any neurological symptoms. On arrival, he had

blood pressure 106/36 mm Hg, heart rate 127 bpm,

temperature 39°C, and oxygen saturation 99% on air.

He had reduced pulse volume with normal capillary

refilling time. Systemic examination was otherwise

unremarkable. Full blood count analysis revealed

a haemoglobin level of 14.7 g/dL, white cell count

of 9.31 × 109/L, and platelet count of 240 × 109/L.

The patient’s blood test results were positive for

dengue non-structural protein 1, and negative for

dengue immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin

G. His renal profile was normal, with mild raised

liver enzymes: alanine aminotransferase 82 U/L and

aspartate aminotransferase 310 U/L.

In view of the tachycardia and reduced pulse

volume, he was treated as a case of severe dengue

fever with compensated shock. He was admitted to

the intensive care unit and treated with fluid boluses

according to standard protocol. On day 3 of illness he

developed severe plasma leakage and was intubated

for respiratory distress. His condition soon stabilised

and he remained normotensive throughout his stay

in intensive care unit. He was extubated on day 7

when he entered a recovery phase. At that time, he

had a normal level of consciousness.

Three days later (day 10 of illness), he became

encephalopathic, disorientated and able to obey

only single step commands. Examination revealed

a Glasgow Coma Scale score of E4V4M6 with

normal motor power over both upper and lower

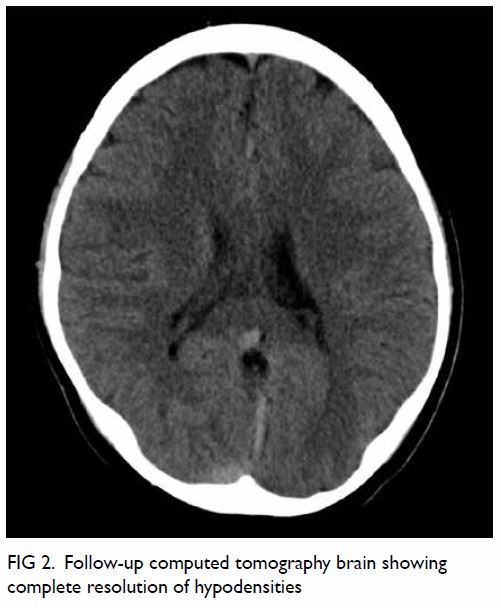

limbs. A plain computed tomography (CT) brain

scan showed hypodensities at bilateral occipital

regions and semiovale, predominantly involving the

white matter, and suggestive of posterior reversible

encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) [Fig 1]. A diagnostic lumbar puncture was offered but refused

by his parents. Blood and urine cultures were

negative and he was prescribed a 1-week course of intravenous meropenem. He subsequently improved

and was discharged well on day 16. Serum dengue

polymerase chain reaction was later confirmed as

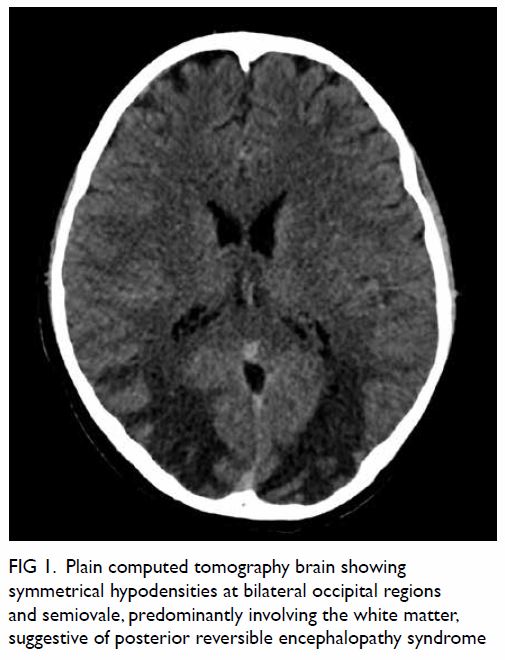

DEN-2. At clinic follow-up, the patient was well and

asymptomatic. Repeat CT brain at 3 months showed

complete resolution of white matter oedema (Fig 2).

Figure 1. Plain computed tomography brain showing symmetrical hypodensities at bilateral occipital regions and semiovale, predominantly involving the white matter, suggestive of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

Discussion and conclusion

Dengue fever is an important public health problem

in the tropics. At present, it is endemic in more

than 100 countries. The World Health Organization

estimates there to be around 390 million infections

per year with 96 million manifesting clinically.1 The

clinical features vary from those of a mild febrile illness to severe dengue with systemic complications.

Systemic complications include shock, bleeding,

plasma leakage, myocarditis and, in some patients,

neurological complications. The latter include

dengue encephalitis, dengue encephalopathy,

meningitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis,

and Guillain-Barré syndrome.2 Posterior reversible

encephalopathy syndrome can occur but is rare.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy

syndrome is a distinct clinicoradiological syndrome

characterised by headache, seizures, altered

consciousness and visual disturbances with the

presence of reversible brain vasogenic oedema.3 It can be caused by acute hypertension, hypertensive

disease in pregnancy, autoimmune diseases

(systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis),

immunosuppressants, cytotoxic agents, renal failure,

and infection. An infectious aetiology such as virus

and gram-positive or gram-negative sepsis have all

been associated with PRES as has dengue virus.4 5

The pathophysiology of PRES in dengue is still

not fully understood. It is postulated to be related

to endothelial dysfunction4 that subsequently leads

to vasogenic oedema and decreased cerebral blood

flow. In addition, inflammatory cytokines can

increase vascular permeability with consequent

interstitial brain oedema.3 Neuroimaging is essential

for diagnosis with characteristics that include

vasogenic oedema in the parieto-occipital region of

both cerebral hemispheres. The subcortical white

matter is always affected. Three primary patterns

of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain have been described, namely dominant parieto-occipital

pattern, holohemispheric watershed pattern, and

superior frontal sulcus pattern. Treatment is mainly

supportive with removal of causative factors.

In our patient, diagnosis of PRES was

based on clinical and radiological features. He

developed acute onset encephalopathy coupled with

typical neuroimaging features. Brain CT showed

symmetrical hypodensities at bilateral occipital

lobes and predominantly involving white matter,

suggestive of PRES. He was treated conservatively,

and he improved. Follow-up CT brain revealed

complete resolution of vasogenic oedema. In terms of

aetiology, our patient had no history of hypertension

or autoimmune disease or recent cytotoxic agent. In

addition, blood pressure remained stable throughout

his hospital stay with no decompensated shock. The

limitation of our case is the lack of MRI facilities.

Compared with CT, MRI better delineates lesions

and is preferable if available.

In terms of timing of PRES in relation to dengue

fever, PRES has been reported to have occurred

on day 5 to 6 of illness in one case,4 and within the

non-structural protein 1 antigen positive period

(first 7 days of illness) in another.5 In our case, it

occurred on day 10 of illness and was considered

compatible with the cases reported previously. A

diagnosis of PRES secondary to dengue is one of

exclusion, supported by typical imaging features and

within a reasonable time frame. Alternative causes of

PRES should be actively searched for and excluded

in every case.

In conclusion, this case highlights PRES as

an important differential diagnosis in a dengue

patient with neurological deficits. It is important to

differentiate PRES from other clinical syndromes

since management is mainly supportive and by

controlling the underlying conditions. Neuroimaging

plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis

in the compatible clinical context. The prognosis

of PRES is usually good. However, more studies

are needed to further elucidate the underlying

pathophysiology of PRES in dengue.

Author contributions

Concept or design: SW Cheo and QJ Low.

Acquisition of data: SW Cheo and HJ Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: HJ Wong and EK Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: SW Cheo and QJ Low.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SW Cheo and HJ Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: HJ Wong and EK Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: SW Cheo and QJ Low.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written informed consent

for all treatments and procedures, and written consent for

publication.

References

1. World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue: Fact sheet. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue.Accessed 4 Nov 2019.

2. Murthy JM. Neurological complications of dengue infection. Neurol India 2010;58:581-4. Crossref

3. Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Posterior reversible

encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological

manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding

questions. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:914-25. Crossref

4. Mai NT, Phu NH, Nghia HD, et al. Dengue-associated posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, Vietnam.

Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24:402-4. Crossref

5. Sohoni CA. Bilateral symmetrical parieto occipital involvement in dengue infection. Ann Indian Acad Neurol

2015;18:358-9. Crossref