Embolisation for thoracic paraspinal extramedullary haematopoiesis complicated by haemothorax: a case report

Hong Kong Med J 2026 Feb;32(1):62–5 | Epub 2 Feb 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Embolisation for thoracic paraspinal extramedullary haematopoiesis complicated by haemothorax: a case report

KH Chu, MB, BS; L Xu, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology); HS Fung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr L Xu (xl599@ha.org.hk)

Case presentation

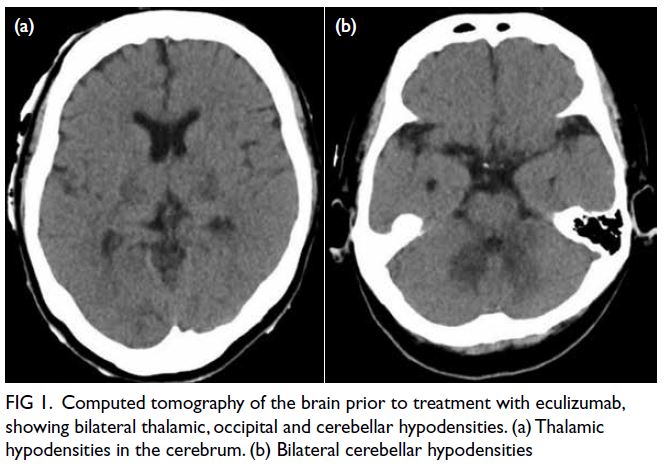

A 37-year-old male with thalassaemia intermedia

(alpha and beta) had undergone cholecystectomy

and splenectomy in childhood, but had received

no regular transfusions or medications since his

haemoglobin (around 8 g/dL) and ferritin levels

(approximately 4300 pmol/L) remained stable.

He had multiple extramedullary haematopoietic

(EMH) lesions in the bilateral paraspinal regions,

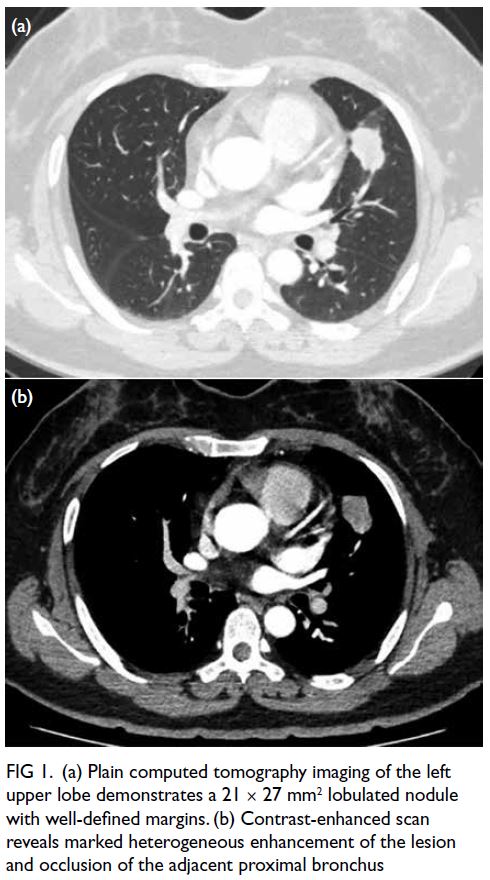

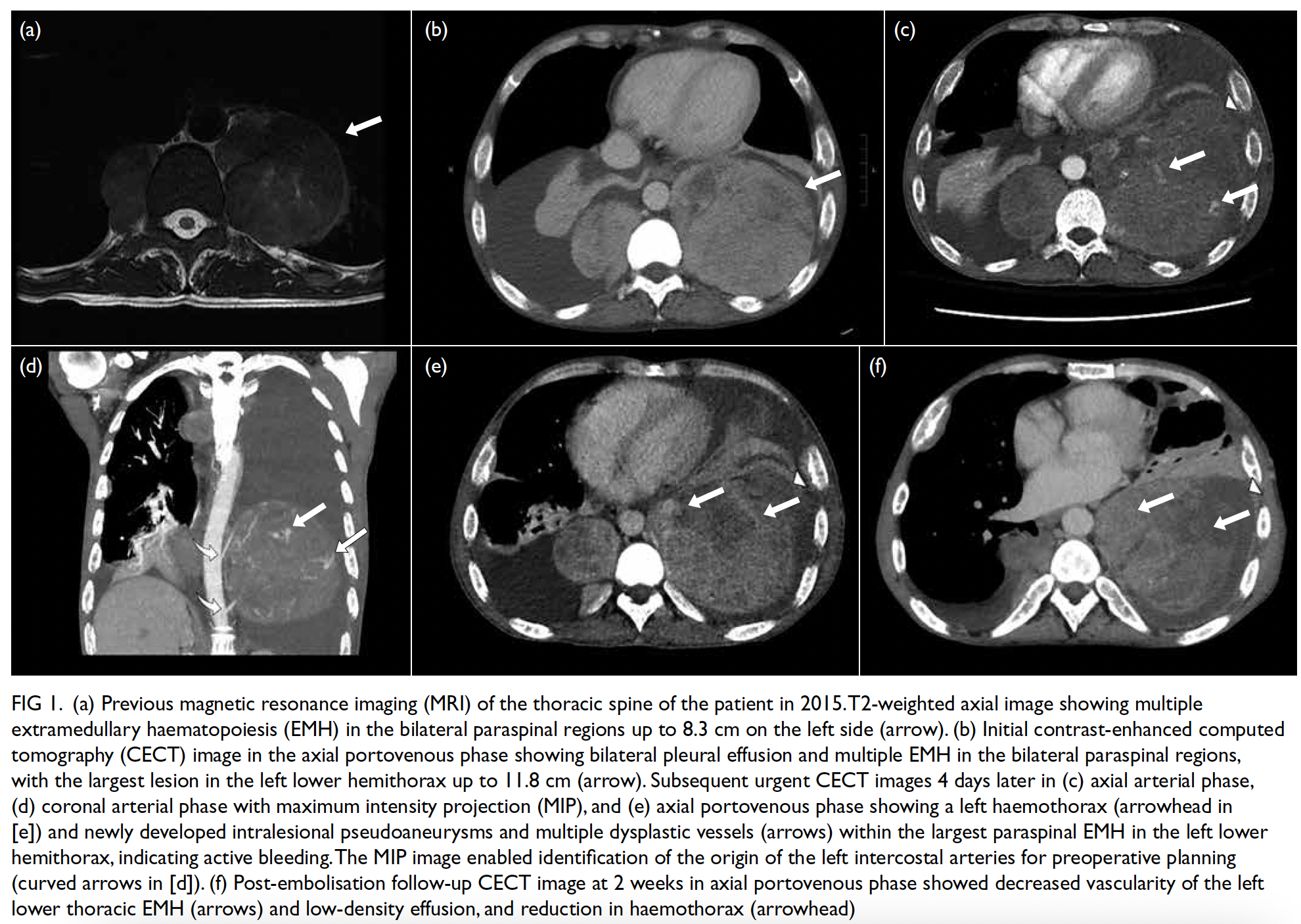

evident on previous magnetic resonance imaging (Fig 1a). Following a recent viral infection in January

2025 with nasopharyngeal swab testing positive for

influenza A and B and respiratory syncytial virus, he

reported back pain and dark-coloured urine. Blood

tests revealed a drop in haemoglobin level to 4.9 g/dL.

The working diagnosis was haemolysis precipitated

by infection. An initial computed tomography (CT)

of the thorax revealed bilateral pleural effusions and

the known EMH, but no evidence of haemorrhage

(Fig 1b).

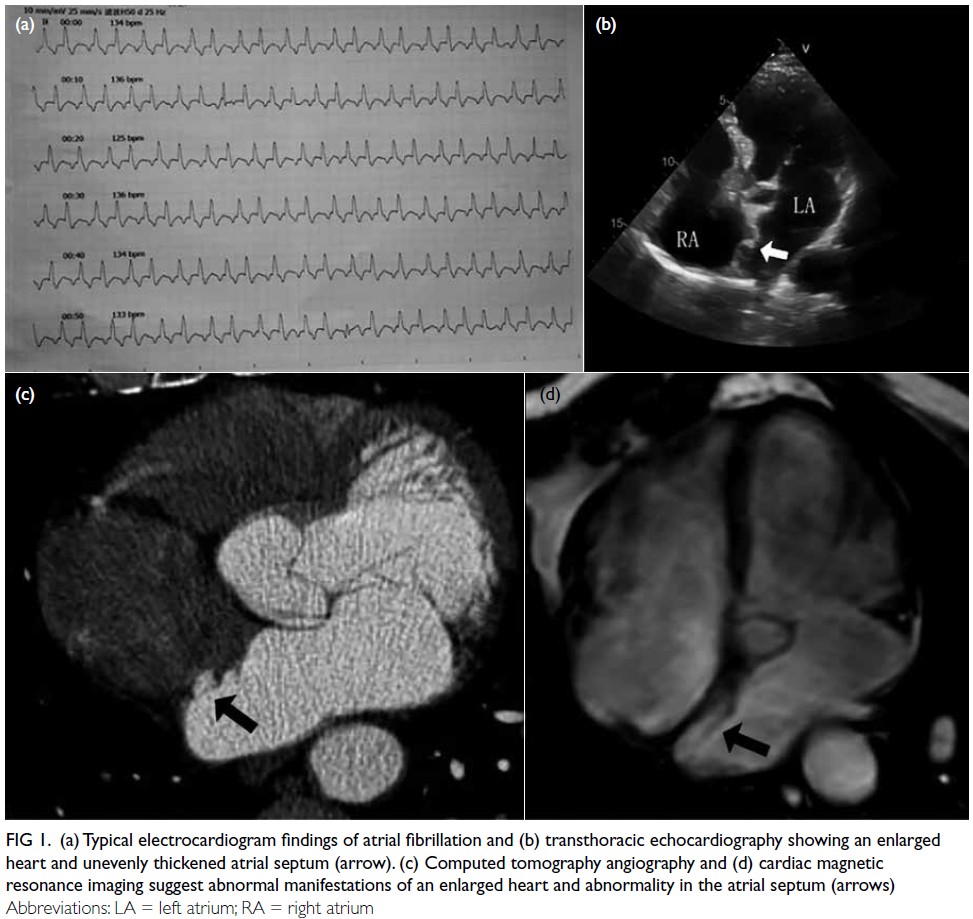

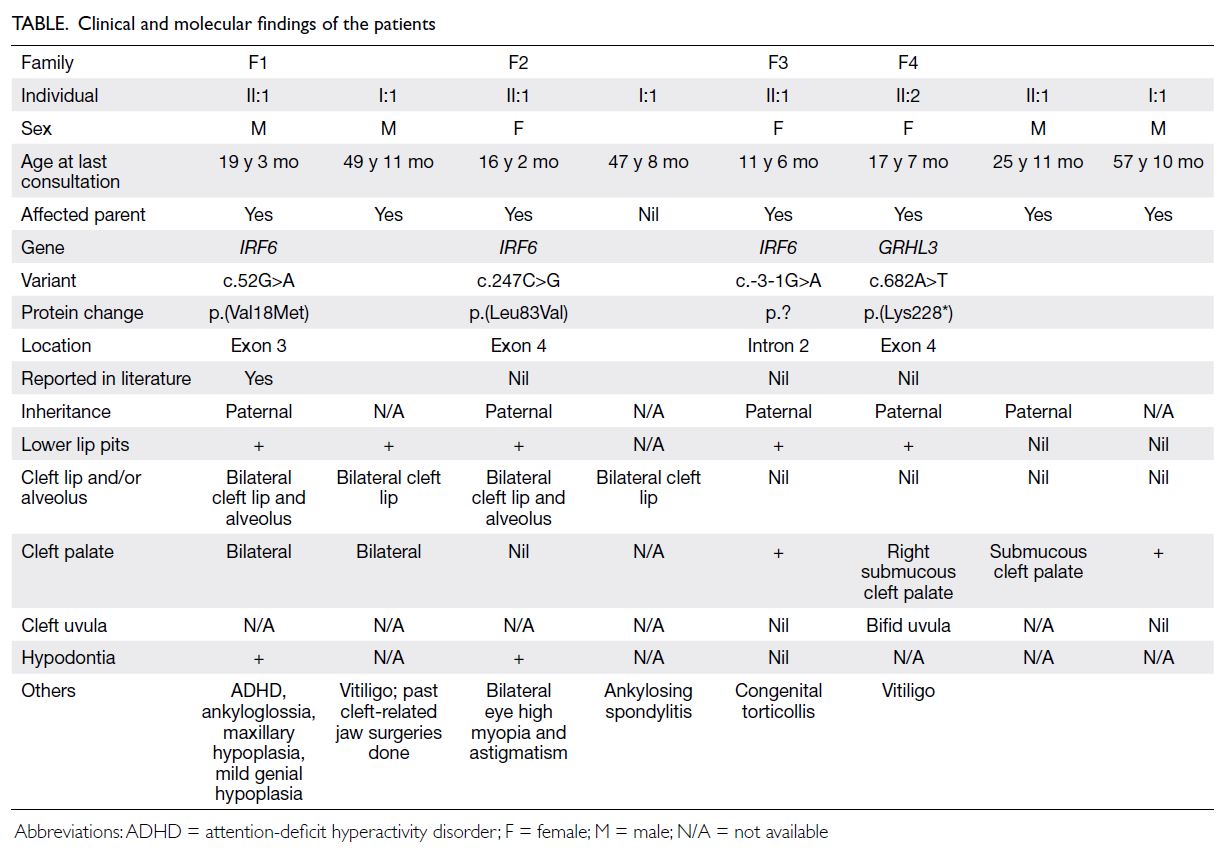

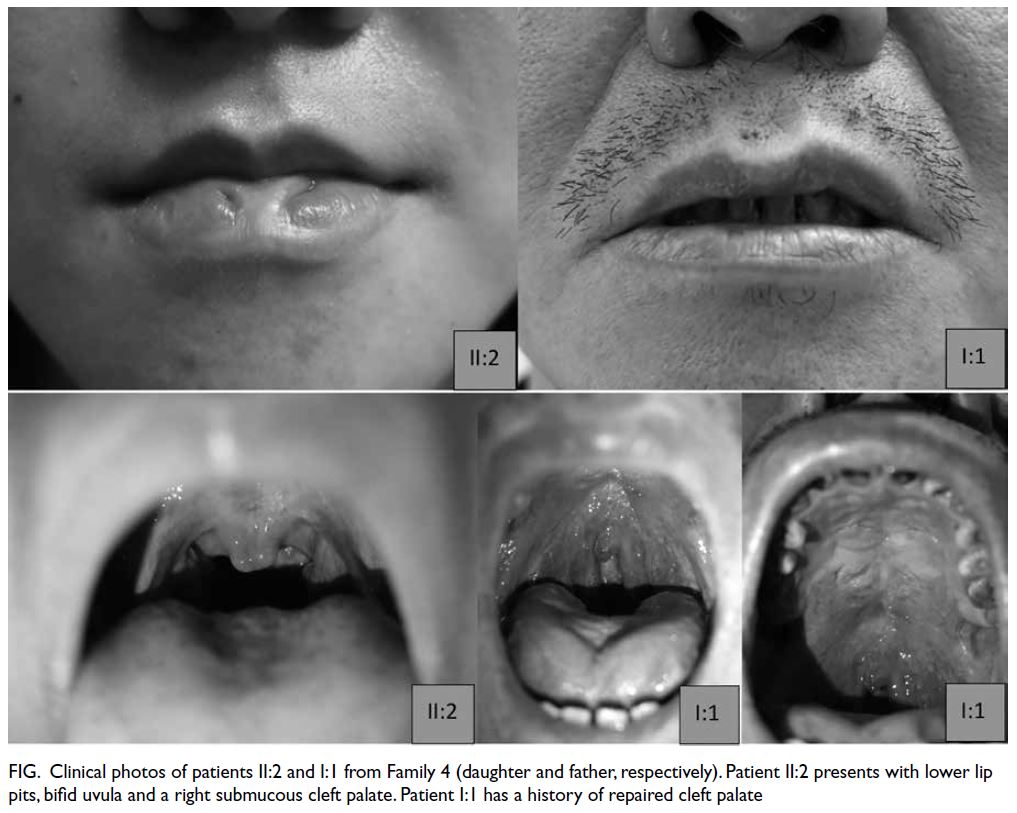

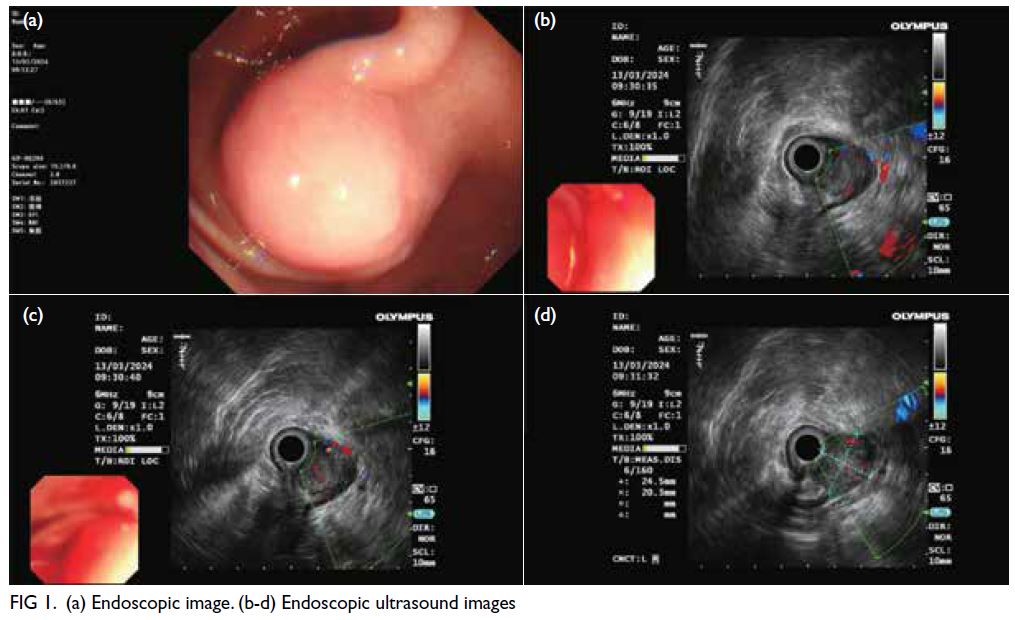

Figure 1. (a) Previous magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine of the patient in 2015. T2-weighted axial image showing multiple extramedullary haematopoiesis (EMH) in the bilateral paraspinal regions up to 8.3 cm on the left side (arrow). (b) Initial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) image in the axial portovenous phase showing bilateral pleural effusion and multiple EMH in the bilateral paraspinal regions, with the largest lesion in the left lower hemithorax up to 11.8 cm (arrow). Subsequent urgent CECT images 4 days later in (c) axial arterial phase, (d) coronal arterial phase with maximum intensity projection (MIP), and (e) axial portovenous phase showing a left haemothorax (arrowhead in [e]) and newly developed intralesional pseudoaneurysms and multiple dysplastic vessels (arrows) within the largest paraspinal EMH in the left lower hemithorax, indicating active bleeding.The MIP image enabled identification of the origin of the left intercostal arteries for preoperative planning (curved arrows in [d]). (f) Post-embolisation follow-up CECT image at 2 weeks in axial portovenous phase showed decreased vascularity of the left lower thoracic EMH (arrows) and low-density effusion, and reduction in haemothorax (arrowhead)

A few days later, the patient developed sudden

chest pain, with tachycardia and hypotension (blood

pressure: 82/43 mm Hg). Urgent CT of the thorax

revealed a left haemothorax and blood products

adjacent to the largest paraspinal EMH in the left

lower hemithorax, along with new intralesional

pseudoaneurysms and multiple dysplastic vessels,

indicative of active bleeding (Fig 1c-e). A left chest

drain was placed, yielding 1.3 L of heavily blood-stained

fluid. He was referred to interventional

radiologists for urgent embolisation to control the

bleeding.

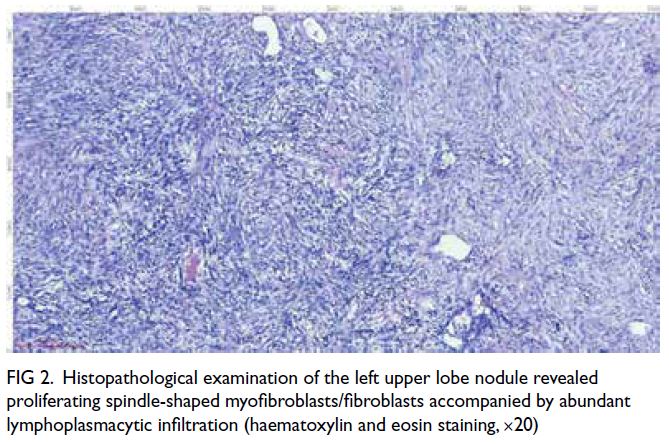

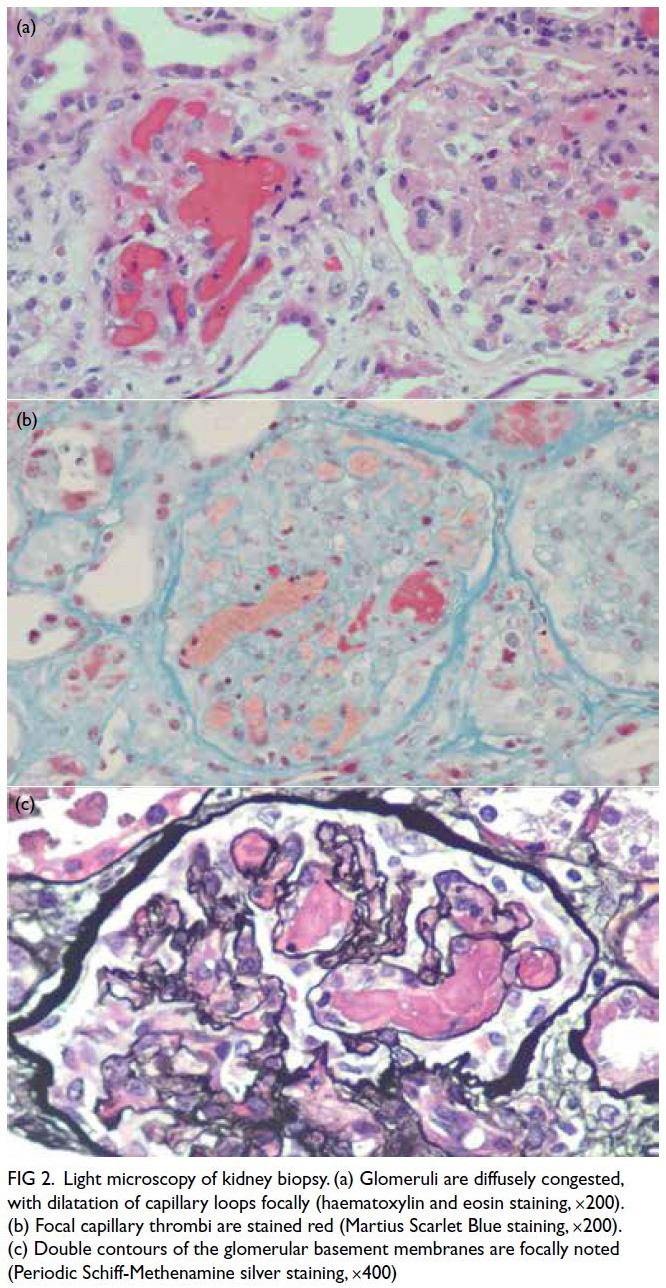

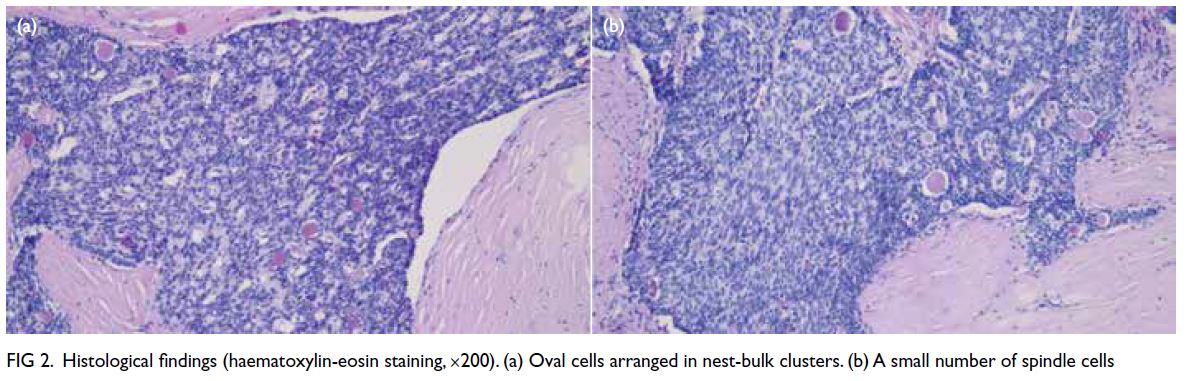

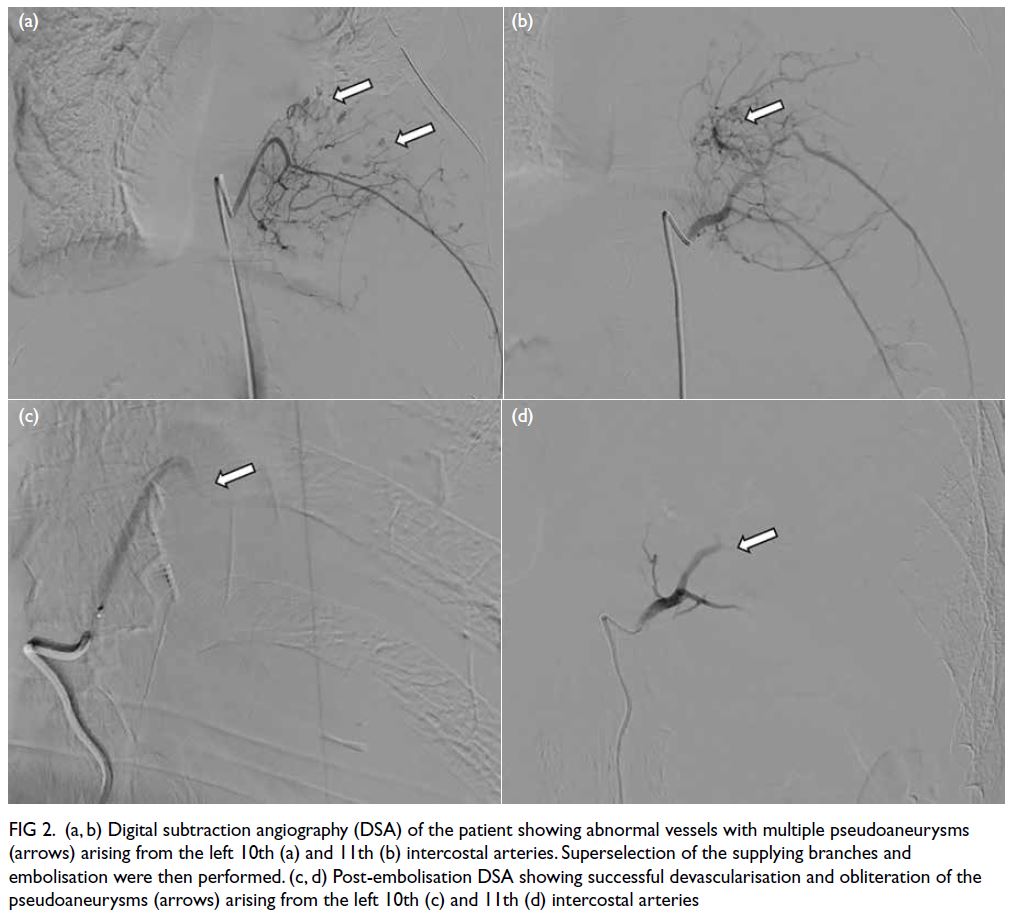

Urgent embolisation was performed under

local anaesthesia. A 5-Fr Mikaelsson catheter (Merit

Medical, South Jordan [UT], United States) was

inserted via transfemoral access to catheterise the

left lower intercostal arteries. Digital subtraction

angiography revealed abnormal, tortuous vessels

with small pseudoaneurysms arising from the left

10th and 11th intercostal arteries and supplying the dominant left lower thoracic EMH (Fig 2a and b). Selective cannulation of these arteries was

performed using a 2.1-Fr Maestro microcatheter

(Merit Medical). Superselective embolisation

was then performed at several branches using a

combination of 700-900 μm Embosphere (Merit

Medical) and 710-1000 μm EGgel (ENGAIN,

Hwaseong-si, South Korea). A postprocedural

angiogram showed successful devascularisation of

the lesion and obliteration of the pseudoaneurysms

(Fig 2c and d).

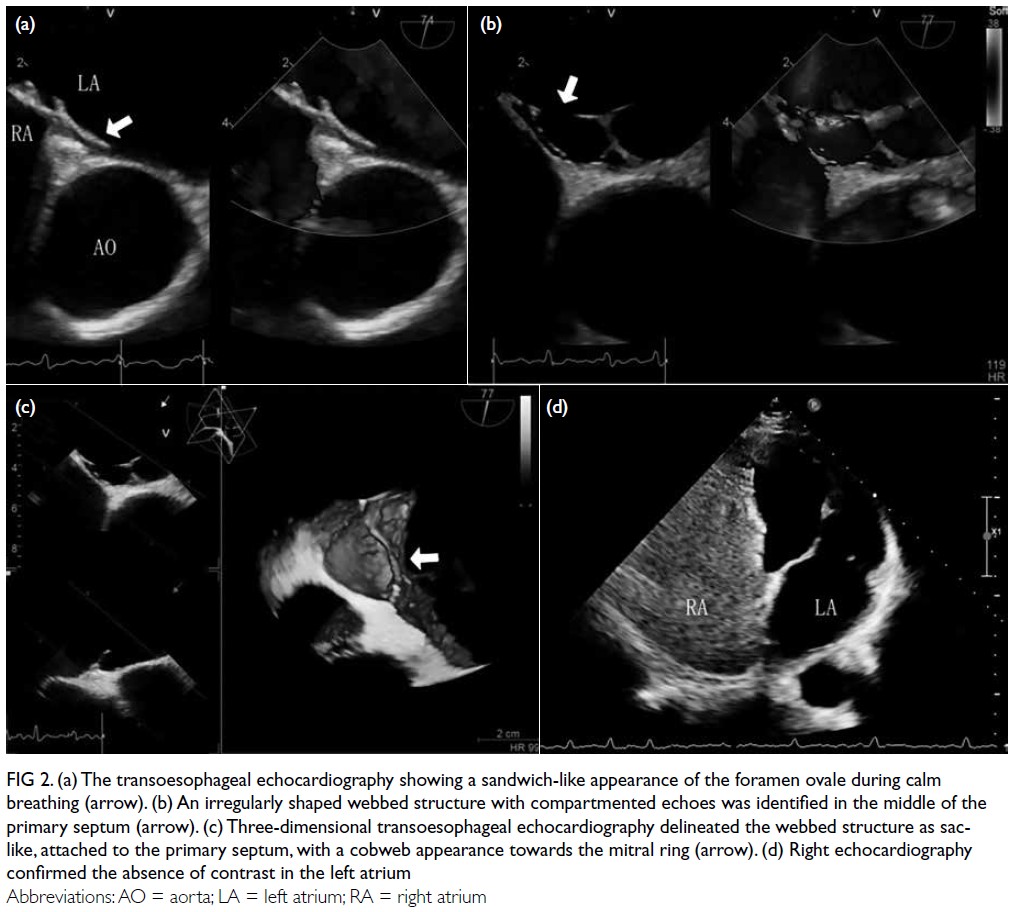

Figure 2. (a, b) Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the patient showing abnormal vessels with multiple pseudoaneurysms (arrows) arising from the left 10th (a) and 11th (b) intercostal arteries. Superselection of the supplying branches and embolisation were then performed. (c, d) Post-embolisation DSA showing successful devascularisation and obliteration of the pseudoaneurysms (arrows) arising from the left 10th (c) and 11th (d) intercostal arteries

Following the procedure, the patient’s vital signs

normalised and there were no neurological deficits.

His haemoglobin level stabilised at 7 to 8 g/dL and

chest drain was later removed due to minimal output.

Follow-up CT 2 weeks later showed a reduction in

the left haemothorax and decreased vascularity of

the left lower thoracic EMH (Fig 1f). The patient was

discharged and remains asymptomatic to date, with

no clinical evidence of re-bleeding.

Discussion

Extramedullary haematopoiesis refers to the

compensatory production of blood cells outside of

the bone marrow, typically occurring in patients with

insufficient bone marrow function, such as those

with thalassaemia. Diagnosis can be made clinically

and radiologically, especially when the lesions are

multifocal or bilateral, exhibiting characteristic

iron deposition or fatty replacement on imaging.1

Paraspinal EMH can lead to complications such as

spinal cord compression or, rarely, haemothorax

due to rupture and bleeding into the pleural cavity.

In our patient, it was hypothesised that haemolysis

from the recent infection increased the demand for

haematopoiesis, stimulating the existing EMH to

recruit additional blood vessels under stress. This

angiogenesis ultimately led to intralesional bleeding,

pseudoaneurysm formation and haemothorax.

There are no established evidence-based

guidelines for the treatment of EMH. Management

depends on lesion size and location, as well as the

patient’s clinical condition.2 In uncomplicated cases,

hypertransfusions aimed at correcting anaemia

and reducing haematopoietic demand can shrink

EMH lesions. Radiotherapy may also be used, as

haematopoietic tissue is radiosensitive and tends

to regress following irradiation. Nonetheless, when

complications such as haemorrhage arise, more

urgent intervention is needed. Thoracotomy with

surgical excision has traditionally been performed,

but emergency surgery carries higher risks of bleeding

and other complications.3 Embolisation has emerged

as a mainstay treatment for many haemorrhagic

conditions due to its versatility and precision. Our

case demonstrated its viability in EMH-related

haemorrhage, enabling accurate identification of

bleeding vessels and prompt haemostasis while

minimising the risks of more invasive surgery.

To ensure a safe and effective embolisation,

meticulous planning and identification of the

target vessels are essential, including superselective

cannulation to prevent non-target embolisation.

Spinal cord feeders can arise from intercostal

arteries and are identified by their characteristic

hairpin appearance as they course medially to

the vertebral pedicle.4 In particular, the artery of

Adamkiewicz, the largest anterior medullary branch

to the anterior spinal artery, commonly arises at

left-sided T9 to T12 levels. Reflux into these arteries

can lead to spinal cord ischaemia. A balance must

be struck between complete devascularisation of

the lesion and the risk of non-target embolisation.

Larger embolic agents, such as particles larger than

350 μm, are theoretically safer as they are too large

to enter the small-calibre spinal arteries. Embolic

agents should be injected slowly under fluoroscopic

guidance, with close monitoring for any interval

appearance of spinal artery supply or reflux.

The choice of embolic agents is important and

depends on factors such as the location of target

vessels, proximity to vital structures, and operator

experience. In our case, a combination of permanent

and temporary particulates was used to achieve

haemostasis. Embospheres are non-absorbable,

calibrated microspheres available in various sizes.

The 700-900 μm size was chosen to prevent entry

into spinal arteries. These provide a long-term

embolic effect with predictable delivery.5 EGgel (710-1000 μm), a porcine-derived gelatin microparticle,

was used for further proximal embolisation. It

offers temporary embolisation, complementing

Embospheres by preventing vessel recanalisation

under high intraluminal pressure.

Haemorrhage associated with EMH is a

critical condition requiring prompt and effective

intervention. Embolisation can be life-saving in

such cases. Although further studies are needed to

assess long-term outcomes, embolisation should be

considered part of the multidisciplinary management

of patients with EMH.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KH Chu, L Xu.

Acquisition of data: KH Chu, L Xu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KH Chu, L Xu.

Drafting of the manuscript: KH Chu, L Xu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: KH Chu, L Xu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KH Chu, L Xu.

Drafting of the manuscript: KH Chu, L Xu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Central Institutional Review

Board of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: CIRB-2025-064-2). The patient provided written informed consent

for all treatments and procedures, and for publication of the

case report, including the accompanying clinical images.

References

1. Hughes M. Rheumatic manifestations of haemoglobinopathies. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2018;20:61. Crossref

2. Gupta S, Krishnan AS, Singh J, Gupta A, Gupta M.

Clinicopathological characteristics and management of

extramedullary hematopoiesis: a review. Pediatr Hematol

Oncol J 2022;7:182-6. Crossref

3. Pornsuriyasak P, Suwatanapongched T, Wangsuppasawad N,

Ngodngamthaweesuk M, Angchaisuksiri P. Massive

hemothorax in a beta-thalassemic patient due to

spontaneous rupture of extramedullary hematopoietic masses: diagnosis and successful treatment. Respir Care 2006;51:272-6.

4. Papalexis N, Peta G, Gasbarrini A, Miceli M, Spinnato P,

Facchini G. Unraveling the enigma of Adamkiewicz:

exploring the prevalence, anatomical variability, and clinical impact in spinal embolization procedures for bone

metastases. Acta Radiol 2023;64:2908-14. Crossref

5. Wang CY, Hu J, Sheth RA, Oklu R. Emerging embolic

agents in endovascular embolization: an overview. Prog

Biomed Eng (Bristol) 2020;2:012003. Crossref

Three video clips showing the webbed left atrial septal pouch and contrast flow are available at

Three video clips showing the webbed left atrial septal pouch and contrast flow are available at