Primary penile tuberculosis masquerading as penile cancer: a case report

Hong Kong Med J 2023 Dec;29(6):554–5 | Epub 2 Nov 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Primary penile tuberculosis masquerading as penile cancer: a case report

Ankitkumar Sharma, MS, DrNB (Urology); Deepak Velmurugan, MB, BS; Kuppurajan Narayanasamy, MS, FRCS (Urology)

Department of Urology, Kovai Medical Center and Hospital, Coimbatore, India

Corresponding author: Dr Ankitkumar Sharma (dr.ankitkumarsharma@gmail.com)

Case presentation

A 53-year-old man from northwest Tamil Nadu,

India presented to our institution in January 2021

with a 3-month history of new-onset phimosis

with swelling of the glans and an ulcer and penile

discharge. The lesion presented initially with

seropurulent discharge from the preputial sac. The

patient later noticed some induration over the dorsal

aspect that progressed further to an ulcer with

frank purulent discharge. He had no family history

of tuberculosis (TB) and no venereal disease or

significant past surgical intervention. He had type 2

diabetes mellitus controlled by regular medication.

His spouse had no significant history of pelvic

inflammatory disease or secondary infertility and

no present complaint of vaginal discharge, lower

abdominal pain or productive cough.

On examination, the patient was of average

built and nourishment. Vital signs were stable and

examination of the respiratory, cardiovascular and

gastrointestinal systems was unremarkable. Local

examination of the external genitalia revealed

staining of garments, phimosis, and an ulcer of

1×1 cm in size over the dorsal aspect of the penis

with foul smelling purulent discharge near the

corona. The glans palpable through the prepuce

was hard in consistency and non-tender. The penile

shaft was indurated up to the base and non-tender.

There was no significant inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Testes, spermatic cord and scrotum were clinically

normal.

Blood investigations revealed haemoglobin

level of 13.1 g/dL, white blood cell count of 6900/mm3,

neutrophil level of 60%, platelet count of 234 000/μL,

and glycated haemoglobin level of 7.8%; serology

showed that human immunodeficiency virus,

hepatitis B surface antigen and syphilis were non-reactive.

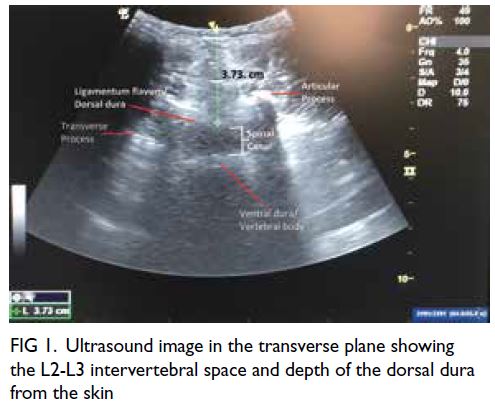

Ultrasound of bilateral groin revealed a

few inguinal nodes bilaterally, with the largest on

the right measuring 8.7 mm. All nodes showed

preserved fatty hilum and normal vascularity.

With the clinical diagnosis of localised

carcinoma penis in mind, the patient was counselled

about the need for intervention in the form of

penile biopsy followed by total amputation of the penis with perineal urethrostomy. Under spinal

anaesthesia, a dorsal slit was made in the penis that

revealed penile oedema with purulent discharge

from the preputial edge, multiple small granulomas

and a hard and purulent cover over the glans. The

glans penis was partially necrosed but the meatus

was preserved. On extension of the dorsal slit to

the base, the shaft was found to be covered in pus

and slough with a hard consistency of the corpora

cavernosa. Penile biopsy was taken from the glans

and shaft. The slit cut surface was approximated at

the base and haemostatic sutures placed over the

glans to let the wound drain. A 16-Fr catheter was

passed. Postoperatively, the patient was started

on 4.5-g piperacillin sodium and tazobactam

sodium via intravenous route three times a day. His

postoperative course was uneventful with the wound

showing purulent discharge, managed with twice

daily saline dressings. The possibility of infectious

origin of the disease was discussed with the patient.

After discussion with the pathologist, a

provisional report was obtained of granulomatous

inflammation with a few areas of necrosis. The need

for culture and sensitivity was discussed with the

patient, but due to financial constraints the patient

was unwilling to proceed. He was initiated on anti-tubercular

therapy as per regional antimicrobial

policy. The final histopathology confirmed

necrotising and granulomatous inflammation, with

no acid-fast bacilli noted.

The patient and his partner were screened

for pulmonary and genitourinary TB after the final

histopathology report. The patient was discharged

on postoperative day 9 with instructions to continue

ATT for 6 months. He was advised to attend a

local clinic for dressing changes every week until

the wound had healed. The wound showed signs

of healing on follow-up (Fig 1). After 6 weeks there

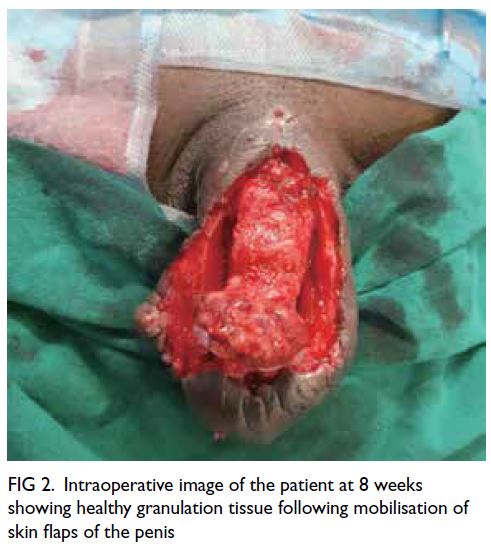

were signs of build-up of slough. At 8 weeks, after

completion of the intensive phase, the patient was

referred for local surgical debridement and wound

closure due to build-up of slough over the wound

surface. He completed the course of ATT and the

wound healed well (Fig 2). He has since developed

erectile dysfunction, probably owing to secondary fibrosis of the corpora cavernosa. He does not desire

treatment at this time.

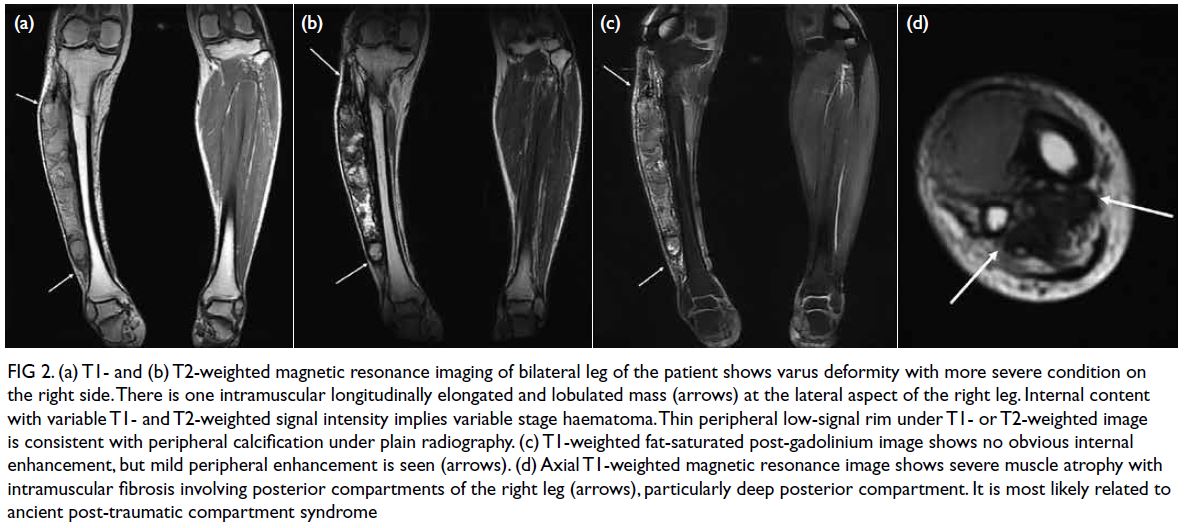

Figure 1. Postoperative image of the patient at 2 weeks following dorsal slit and biopsy showing sloughed tissue extending to the base of penis

Figure 2. Intraoperative image of the patient at 8 weeks showing healthy granulation tissue following mobilisation of skin flaps of the penis

Discussion

Genitourinary TB is the most common form of

extrapulmonary TB, but penile presentation is one of

the least common forms of genitourinary TB (<1%).1

The epididymis (42%) followed by seminal vesicle

(23%), prostate (21%), testis (15%) and vas deferens

(12%) are common sites of presentation.2 In its

primary form, local spread of bacilli from clothing,

ejaculation, endometrial secretions, circumcision,

and intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin has been

reported.2 The secondary form arises due to the

subsequent complication of lung TB or TB in other

parts of the urogenital tract, extending through the

urethra or via a haematogenous route.

Tuberculosis of penis may affect the skin,

glans penis or cavernous bodies. It can mimic penile

carcinoma in presentation, much like our patient.

Tuberculosis affecting the glans penis can present as

tuberculous chancre, papulo-necrotic tuberculoid,

TB cutis orificialis or tuberculous gumma. In most

cases, the lesion takes the form of an ulcer that is

difficult to differentiate from a malignant tumour.

The lesion can be extensive, with involvement of the

urethra and corpus cavernosum. Since young adults

are affected, their partner should always be evaluated

for genital TB.3 Although there are several tests

for diagnosis of TB, biopsy remains confirmatory.

Surgical management may be required in doubtful

cases in spite of successful treatment with ATT.

Organ sparing surgery coupled with ATT should be

the goal of treatment.4

Our experience highlights the similarities in

presentation of penile carcinoma and primary penile

TB, further cementing the need for a dorsal slit prior

to definitive procedure. A high index of suspicion

should be maintained considering the endemic

status of TB in South-East Asian countries. Biopsy

should always be performed in doubtful cases.

Author contributions

Concept or design: A Sharma.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: A Sharma.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: A Sharma.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publishing of data relevant to the case report.

References

1. Nimisha E, Gupta G. Penile lupus vulgaris: a rare presentation of primary cutaneous tuberculosis. Int J STD AIDS 2014;25:969-70. Crossref

2. Amir-Zargar MA, Yavangi M, Ja’fari M, Mohseni MJ. Primary tuberculosis of glans penis: a case report. Urol J 2004;1:278-9.

3. Gangalakshmi C, Sankarmahalingam. Tuberculosis of glans penis—a rare presentation. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:PD05-6. Crossref

4. Rajeev TP, Pranab KR, Phukan PK, Baruna SK, Das Roop R. Tuberculosis of penis mimicking an advanced penile cancer—a case report. Int J Sci Res 2018;7:16-7.