© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Q Fever spondylodiscitis in the presence of

endovascular infections: a case report

Austin SL Lim, MD, DPBO; Azizul AB Sali, MD, MMed; Jason PY Cheung, MS, MD

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Jason PY Cheung (cheungjp@hku.hk)

Case report

In areas endemic for tuberculosis infections, the

presence of infection on imaging and granulomatous

inflammation on histology is often sufficient to

start antituberculous pharmacotherapy. However,

this may not be appropriate in cases of non-tuberculous

granulomatous infection. Rarer causes

of spinal infection should be considered, especially

if the clinical response is suboptimal. We present

an unusual case of granulomatous spinal infection

caused by Coxiella burnetii.

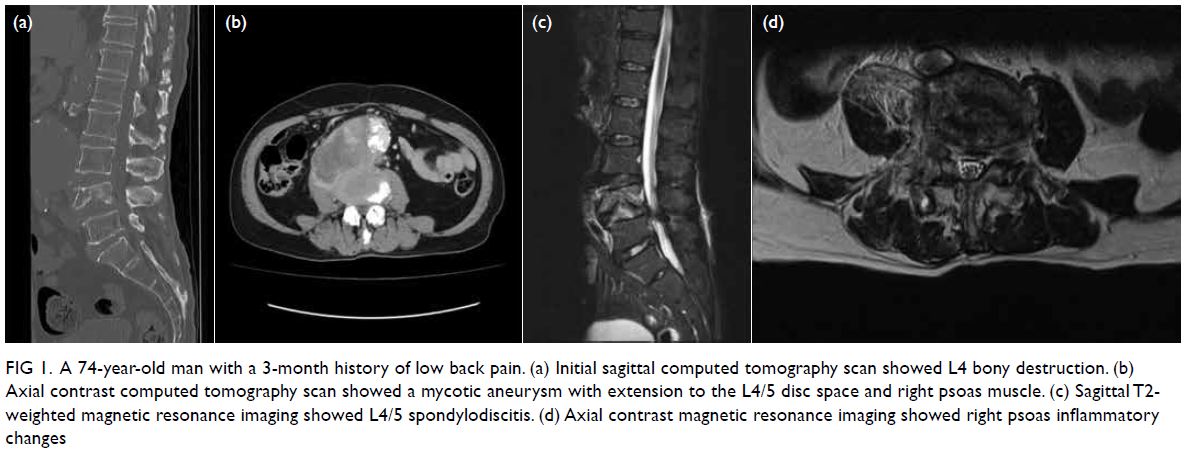

A 74-year-old man from southern China with

no travel history presented with a 3-month history

of low back pain in the absence of neurological

deficit or constitutional symptoms. Co-morbidities

included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and

hyperlipidaemia. There were no symptoms or signs

of endocarditis. Initial plain radiographs showed

lytic destruction of L4 and erosion of the L4-L5 disc

space. Laboratory investigations revealed raised

C-reactive protein (CRP) of 27.6 g/dL and erythrocyte

sedimentation rate of 32 mm/h. Blood culture, Widal

test for Salmonella, HIV testing and acid-fast bacilli

growth in sputum and blood were all negative. There

was no growth of fungus or brucellosis. Magnetic

resonance imaging and computed tomography (CT)

revealed L4/5 spondylodiscitis with psoas and

paravertebral abscesses (Fig 1), and a mycotic

infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm measuring

7.3 × 7.6 × 5.7 cm. He underwent endovascular stenting of the aneurysm. A CT-guided aspiration

of the psoas abscess was negative on Ziehl–Neelsen

and Grocott staining and tuberculous polymerase

chain reaction. Histology confirmed granulomatous

inflammation. After discussion with the microbiologist,

the patient was prescribed intravenous ceftriaxone

2 g per day and metronidazole 1 g per day but

switched to ertapenem 1 g per day due to a poor

clinical response. These antibiotics were used as

empirical therapy. Symptoms subsided and his CRP

normalised to <0.35 g/dL. He was discharged home

and prescribed lifelong amoxicillin/clavulanic acid

375 mg 3 times daily, with levofloxacin 500 mg once

daily for the mycotic aneurysm.

Figure 1. A 74-year-old man with a 3-month history of low back pain. (a) Initial sagittal computed tomography scan showed L4 bony destruction. (b) Axial contrast computed tomography scan showed a mycotic aneurysm with extension to the L4/5 disc space and right psoas muscle. (c) Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed L4/5 spondylodiscitis. (d) Axial contrast magnetic resonance imaging showed right psoas inflammatory changes

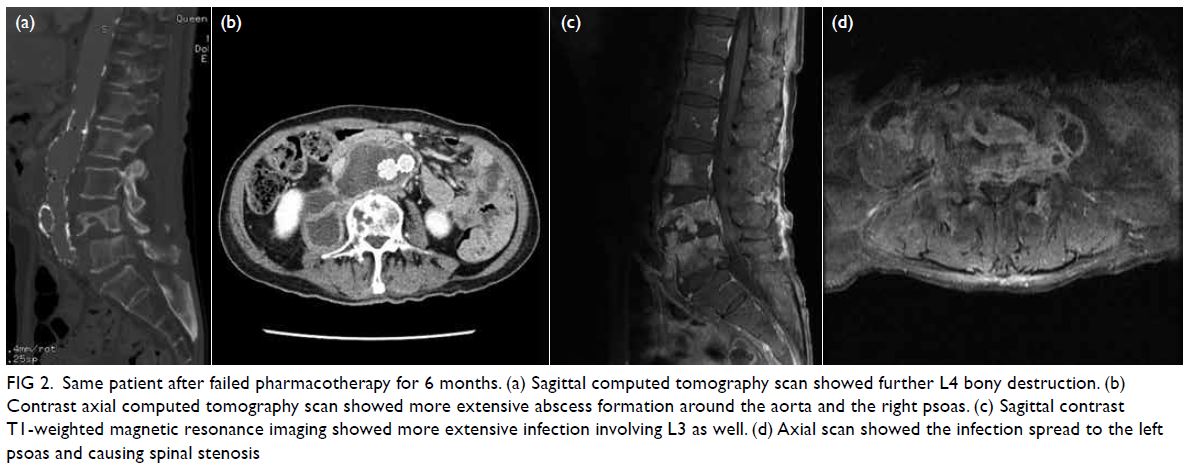

At 6 months after discharge he presented with

recurrent back pain along with radicular symptoms.

Inflammatory markers were elevated with CRP

3.5 g/dL and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 81 mm/h.

The same cultures and serology were negative.

Plain radiographs and CT showed increased bony

destruction of L4. Magnetic resonance imaging

revealed persistent retroperitoneal abscess with

progressive spondylodiscitis (Fig 2). A CT-guided

drainage of his right psoas abscess yielded negative

culture results. Due to the neurological deterioration,

an L3-L5 laminectomy with posterior instrumented

spinal fusion was performed. Anterior column

reconstruction was attempted by the vascular

surgeon but scarring prevented safe access to the

spinal column without aneurysmal injury. The L4-L5 disc material revealed granulomatous inflammation

and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. He

was treated as co-infection with tuberculosis and

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and

was given isoniazid 300 mg, rifampicin 450 mg,

and ethambutol 800 mg once daily, and linezolid

600 mg every 12 hours. His inflammatory markers

normalised but back pain persisted.

Figure 2. Same patient after failed pharmacotherapy for 6 months. (a) Sagittal computed tomography scan showed further L4 bony destruction. (b) Contrast axial computed tomography scan showed more extensive abscess formation around the aorta and the right psoas. (c) Sagittal contrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed more extensive infection involving L3 as well. (d) Axial scan showed the infection spread to the left psoas and causing spinal stenosis

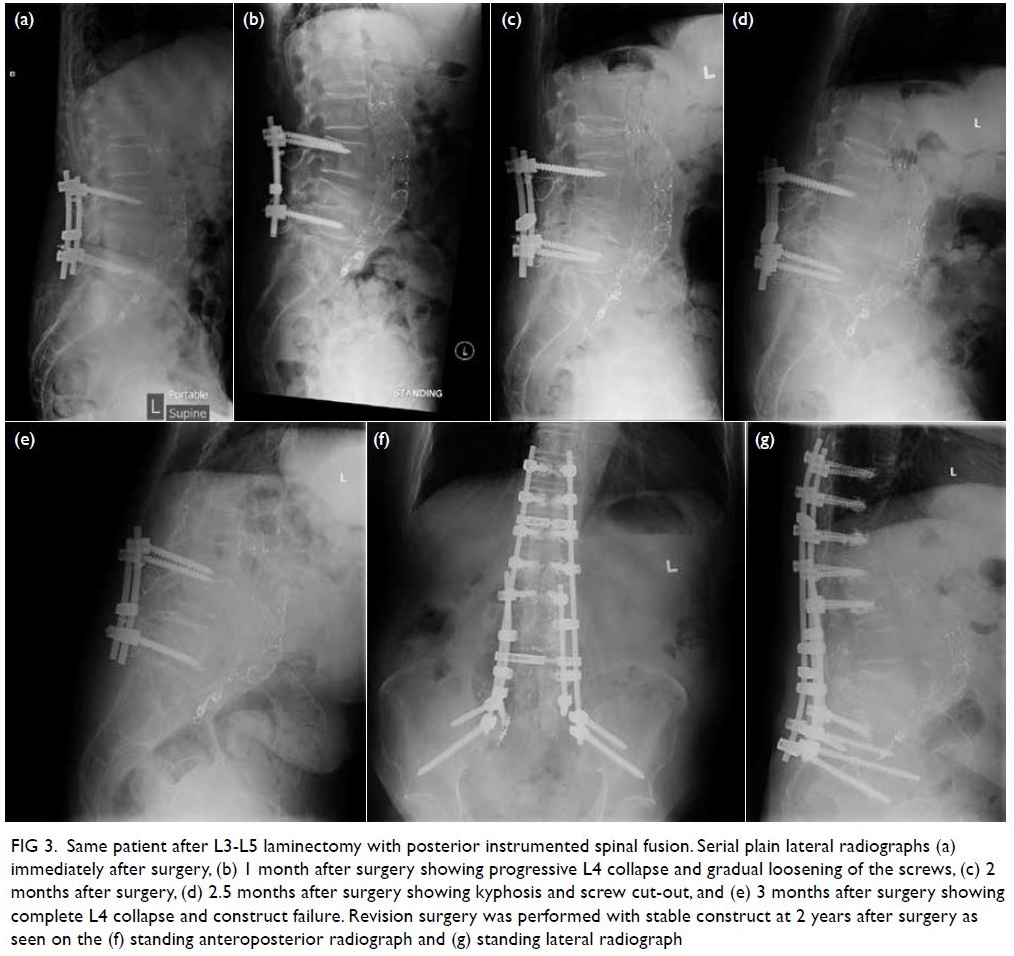

Serial radiographs showed implant failure

with further destruction of L4 (Fig 3) due to the

lack of anterior column support. Revision posterior

instrumented fusion was performed 3 months

after the initial surgery from T10 to the pelvis with

cement augmentation after removal of the loosened

L3-L5 implants. Intra-operative findings were friable

tissue and osteoporotic bone. Histology still showed

granulomatous inflammation but other cultures were

negative. Due to the persistent infection with negative

cultures, serology for C burnetii was performed and

revealed increased phase I and phase II polyvalent

antibodies with titre results of 3200 for both. The

patient was diagnosed with chronic Q fever and was

given lifelong hydroxychloroquine sulphate 200 mg

every 8 hours and doxycycline hyclate 100 mg every

12 hours owing to the presence of the endovascular

stent and spinal instrumentation. Serial monitoring

of Q fever serology was performed every 6 months.

At 2 years after surgery, he remains symptom free

with no implant loosening.

Figure 3. Same patient after L3-L5 laminectomy with posterior instrumented spinal fusion. Serial plain lateral radiographs (a) immediately after surgery, (b) 1 month after surgery showing progressive L4 collapse and gradual loosening of the screws, (c) 2 months after surgery, (d) 2.5 months after surgery showing kyphosis and screw cut-out, and (e) 3 months after surgery showing complete L4 collapse and construct failure. Revision surgery was performed with stable construct at 2 years after surgery as seen on the (f) standing anteroposterior radiograph and (g) standing lateral radiograph

Discussion

First described in 1937, Q fever is caused by

C burnetii and can be found worldwide with

an overall prevalence of 10%.1 2 Inoculation is

through direct contact, ingestion or inhalation of

contaminated materials. Traditionally it is thought

that contact with cows, goats, sheep or cats causes

this disease, but it is not always the case. In chronic Q

fever, endocarditis is the most common presentation, seen in 60% to 70% of cases. Other manifestations

include hepatitis, pericarditis, myocarditis, vascular

infections, and osteoarticular infection.3 Diagnosis

is usually by serological testing but can also be on

smears or frozen tissue with Giemsa staining that

reveals doughnut granulomas. Although serology

shows only indirect evidence of infection, it is a

simpler and reliable technique. In acute Q fever,

testing is performed for antibodies against phase II

antigens. In chronic Q fever, testing is for antibodies

against phase I antigens. Diagnosis is confirmed if

immunoglobulin G titre exceeds 1/800. Cultures are

not commonly performed due to its high infectivity

and is not available in our laboratory.

Osteoarticular Q fever infections are rare. One

study from France showed that only 7.3% of all their

patients with Q fever manifested with osteoarticular

infection.4 The most common form of Q fever

osteoarticular infection is chronic osteomyelitis. This

is usually a result of contamination from a previous

open fracture or prosthetic joints and vascular grafts.4

Adults usually present with an infected prosthetic

joint and children with multifocal osteomyelitis.1

A review of this case revealed that the patient had

previously travelled to Guangdong province in China

and had contact with farm animals. This was the only

potential source of infection from his history. A high

index of suspicion is needed for diagnosis, as seen in this

case, because a delay in treatment can lead to multiple

surgeries. Despite being in an endemic area for spinal

tuberculosis,5 other rarer causes of spondylodiscitis

with granulomatous inflammation must be considered.

These include other bacteria such as Brucellosis,

melioidosis, actinomycosis, and Bartonella infections.

Spirochetes, fungi, toxoplasmosis, and viruses such as

infectious mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus, measles,

and mumps are also potential causes. The presence

of endovascular infection with spondylodiscitis with

granulomatous inflammation and negative cultures

should raise the alarm for potential Q fever. Patients are commonly misdiagnosed and treated with prolonged

antimicrobials and surgery without improvement.

Author contributions

Concept or design: JPY Cheung.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JPY Cheung.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JPY Cheung.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JPY Cheung was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no

conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and provided informed consent for all treatments

and procedures and consent for publication.

References

1. El-Mahallawy HS, Lu G, Kelly P, et al. Q fever in China:

a systematic review, 1989-2013. Epidemiol Infect

2015;143:673-81. Crossref

2. Fantoni M, Trecarichi EM, Rossi B, et al. Epidemiological

and clinical features of pyogenic spondylodiscitis. Eur Rev

Med Pharmacol Sci 2012;16 Suppl 2:2-7.

3. Landais C, Fenollar F, Constantin A, et al. Q fever

osteoarticular infection: four new cases and a review of the

literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2007;26:341-7. Crossref

4. Melenotte C, Protopopescu C, Million M, et al. Clinical

features and complications of Coxiella burnetii infections

from the French National Reference Center for Q fever.

JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e181580. Crossref

5. Chan-Yeung M, Noertjojo K, Tan J, Chan SL, Tam CM. Tuberculosis in the elderly in Hong Kong. Int J Tuberc

Lung Dis 2002;6:771-9.