EDITORIAL

Living well with kidney disease by patient and

care partner empowerment: kidney health for everyone everywhere

Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, PhD1 #; Philip KT Li, MD2 #; Ekamol Tantisattamo, MD, MPH3; Latha Kumaraswami, BA4 #; Vassilios Liakopoulos, MD, PhD5 #; SF Lui, MD6 #; Ifeoma Ulasi, MD7 #; Sharon Andreoli, MD8 #; Alessandro Balducci, MD9 #; Sophie Dupuis, MA10 #; Tess Harris, MA11; Anne Hradsky, MA10; Richard Knight, MBA12; Sajay Kumar, BCom4; Maggie Ng13; Alice Poidevin, MA10; Gamal Saadi, MD14 #; Allison Tong, PhD15

1 The International Federation of Kidney Foundation–World Kidney Alliance (IFKF-WKA), Division of Nephrology and Hypertension and Kidney Transplantation, University of California Irvine, Orange, California, United States

2 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Carol & Richard Yu PD Research Centre, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 Division of Nephrology, Hypertension and Kidney Transplantation, Department of Medicine, University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Orange, California, United States

4 Tanker Foundation, Chennai, India

5 Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, 1st Department of Internal Medicine, AHEPA Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

6 Hong Kong Kidney Foundation and the International Federation of Kidney Foundations–World Kidney Alliance, The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

7 Renal Unit, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Nigeria, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria

8 James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, United States

9 Italian Kidney Foundation, Rome, Italy

10 World Kidney Day Office, Brussels, Belgium

11 Polycystic Kidney Disease Charity, London, United Kingdom

12 American Association of Kidney Patients, Tampa, Florida, United States

13 Hong Kong Kidney Foundation, Hong Kong

14 Nephrology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt

15 Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

# Members of the World Kidney Day Steering Committee

Full

paper in PDF

Full

paper in PDF

Living with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is

associated with hardships for patients and their

care partners. Empowering patients and their care

partners, including family members or friends

involved in their care, may help minimise the burden

and consequences of CKD-related symptoms to

enable life participation. There is a need to broaden

the focus on living well with kidney disease and

re-engagement in life, including an emphasis on

patients being in control. The World Kidney Day

(WKD) Joint Steering Committee has declared

2021 the year of ‘Living Well with Kidney Disease’

in an effort to increase education and awareness on

the important goal of patient empowerment and

life participation. This calls for the development

and implementation of validated patient-reported

outcome measures to assess and address areas of life

participation in routine care. It could be supported

by regulatory agencies as a metric for quality care

or to support labelling claims for medicines and

devices. Funding agencies could establish targeted calls for research that address the priorities of

patients. Patients with kidney disease and their care

partners should feel supported to live well through

concerted efforts by kidney care communities

including during pandemics. In the overall wellness

programme for kidney disease patients, the need

for prevention should be reiterated. Early detection

with a prolonged course of wellness despite kidney

disease, after effective secondary and tertiary

prevention programmes, should be promoted.

World Kidney Day 2021 continues to call for

increased awareness of the importance of preventive

measures throughout populations, professionals,

and policy makers, applicable to both developed and

developing countries.

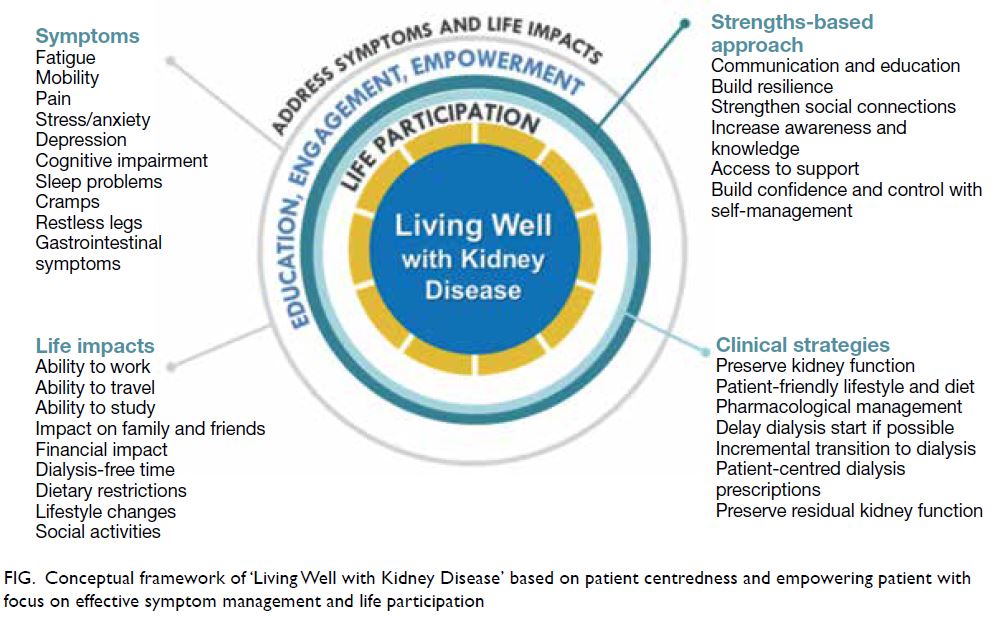

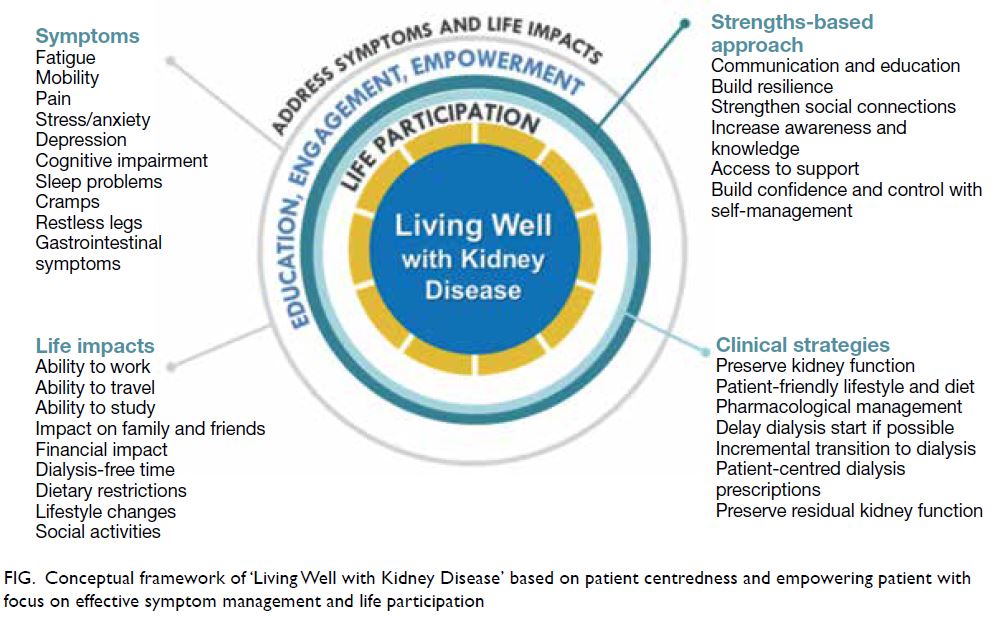

Patient priorities for living well: a

focus on life participation

Chronic kidney disease, its associated symptoms,

and its treatment, including medications, dietary and fluid restrictions, and kidney replacement

therapy can disrupt and constrain daily living, and

impair the overall quality of life of patients and their

family members. Consequently, this can also impact

treatment satisfaction and clinical outcomes.

1

Despite this, the past several decades have seen

limited improvement in the quality of life of people

with CKD.

1 To advance research, practice, and policy,

there is increasing recognition of the need to identify

and address patient priorities, values, and goals.

1

Several regional and global kidney health

projects have addressed these important questions

including the Standardised Outcomes in Nephrology

with more than 9000 patients, family members, and

healthcare professionals from over 70 countries.

2 3

Across all treatment stages, including CKD, dialysis

and transplantation, Standardised Outcomes in

Nephrology participating children and adults with

CKD consistently gave higher priority to symptoms

and life impacts than healthcare professionals.

2 3 In

comparison, healthcare professionals gave higher

priority to mortality and hospitalisation than

patients and family members. The patient-prioritised

outcomes are shown in the

Figure. Irrespective

of the type of kidney disease or treatment stage,

patients wanted to be able to live well, maintain their

role and social functioning, protect some semblance

of normality, and have a sense of control over their

health and well-being.

Figure.

Figure. Conceptual framework of ‘Living Well with Kidney Disease’ based on patient centeredness and empowering patient with

focus on effective symptom management and life participation

Life participation, defined as the ability to do

meaningful activities of life including, but not limited

to, work, study, family responsibilities, travel, sport, social, and recreational activities, was established

a critically important outcome across all treatment

stages of CKD.

1 2 The quotations from patients with

kidney disease provided in the

Box demonstrates how

life participation reflects the ability to live well with

CKD.

4 According to the World Health Organization

(WHO), participation refers to “involvement in a life

situation.”

5 This concept is more specific than the

broader construct of quality of life. Life participation

places the life priorities and values of those affected

by CKD and their family at the centre of decision

making. The World Kidney Day Steering Committee

calls for the inclusion of life participation, a key

focus in the care of patients with CKD, to achieve

the ultimate goal of living well with kidney disease.

This calls for the development and implementation

of validated patient-reported outcome measures,

that could be used to assess and address areas of

life participation in routine care. Monitoring of

life participation could be supported by regulatory

agencies as a metric for quality care or to support

labelling claims for medicines and devices. Funding

agencies could establish targeted calls for research

that address the priorities of patients, including life

participation.

Box.

Box. Quotations from patients with chronic kidney disease related to priorities for living well

Patient empowerment, partnership, and a paradigm shift towards a strengths-based approach to care

Patients with CKD and their family members including care partners should be empowered to

achieve the health outcomes and life goals that are

meaningful and important to them. The WHO defines

patient empowerment as “a process through which

people gain greater control over decisions or actions

affecting their health,”

6 which requires patients to

understand their role, to have knowledge to be able

to engage with clinicians in shared decision making,

skills, and support for self-management. For patients

receiving dialysis, understanding the rationale for a

lifestyle change, having access to practical assistance

and family support promoted patient empowerment,

while feeling limited in life participation undermined

their sense of empowerment.

7

The World Kidney Day Steering Committee

advocates for strengthened partnership with patients

in the development, implementation, and evaluation

of interventions for practice and policy settings, that

enable patients to live well with kidney diseases.

This needs to be supported by consistent, accessible,

and meaningful communication. Meaningful

involvement of patients and family members across

the entire research process, from priority setting and

planning the study through to dissemination and

implementation, is now widely advocated.

8 There

have also been efforts, such as the Kidney Health

Initiative, to involve patients in the development of

drugs and devices to foster innovation.

9

We urge for greater emphasis on a strengths-based

approach as outlined in the

Table, which

encompasses strategies to support patient resilience,

harness social connections, build patient awareness

and knowledge, facilitate access to support,

and establish confidence and control in self-management. The strengths-based approach is in

contrast to the medical model where chronic disease

is traditionally focussed on pathology, problems,

and failures.

10 Instead, the strengths-based approach

acknowledges that each individual has strengths and

abilities to overcome the problems and challenges

faced, and requires collaboration and cultivation of

the patient’s hopes, aspirations, interests, and values.

Efforts are needed to ensure that structural biases,

discrimination, and disparities in the healthcare

system also need to be identified, so all patients are

given the opportunity to have a voice.

Table.

Table. Suggested strategies for ‘living well with chronic kidney disease’ using a strengths-based approach

The role of care partner

A care partner is often an informal caregiver who is

also a family member of the patient with CKD.

11 They

may take on a wide range of responsibilities including

coordinating care (including transportation to

appointments), administration of treatment

including medications, home dialysis assistance,

and supporting dietary management. Caregivers of

patients with CKD have reported depression, fatigue,

isolation, and also burnout. The role of the care

partner has increasingly become more important

in CKD care given the heightened complexity in

communicative and therapeutic options including

the expansion of telemedicine under the coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and given the

goal to achieve higher life expectancy with CKD.

12

The experience of caring for a partially incapacitated

family member with progressive CKD can represent

a substantial burden on the care partner and may

impact family dynamics. Not infrequently, the career goals and other occupational and leisure aspects

of the life of the care partner are affected because

of CKD care partnership, leading to care partner

overload and burnout. Hence, the above-mentioned

principles of life participation need to equally apply

to care partners as well as all family members and

friends involved in CKD care.

Living with kidney disease in low-income

regions

In low and lower-middle-income countries including

in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin

America, patient’s ability to self-manage or cope

with the chronic disease vary but may often be

influenced by internal factors including spirituality,

belief system, and religiosity, and external factors

including appropriate knowledge of the disease,

poverty, family support system, and one’s grit

and social relations network. The support system

comprising healthcare providers and caregivers plays

a crucial role as most patients rely on them in making

decisions, and for the necessary adjustments in their

health behaviour.

13 In low-income regions, where

there are often a relatively low number of physicians

and even lower number of kidney care providers

per population especially in rural areas, a stepwise

approach can involve local and national stakeholders

including both non-governmental organisations and

government agencies by (1) extending kidney patient

education in rural areas; (2) adapting telehealth

technologies if feasible to educate patients and train

local community kidney care providers, and (3)

implementing effective retention strategies for rural

kidney health providers including adapting career

plans and competitive incentives.

Many patients in low-resource settings present

in very late stage needing to commence emergency dialysis.

14 The very few fortunate ones to receive

kidney transplantation may acquire an indescribable

chance to normal life again, notwithstanding the

high costs of immunosuppressive medications in

some countries. For some patients and care partners

in low-income regions, spirituality and religiosity

may engender hope, when ill they are energised

by the anticipation of restored health and spiritual

wellbeing. For many patients, informing them

of a diagnosis of kidney disease is a harrowing

experience both for the patient (and caregivers)

and the healthcare professional. Most patients

present to kidney physicians (usually known as

“renal physicians” in many of these countries) with

trepidations and apprehension. It is rewarding

therefore to see the patient’s anxiety dissipate after

reassuring him or her of a diagnosis of simple

kidney cysts, urinary tract infection, simple kidney

stones, solitary kidneys, etc, that would not require

extreme measures like kidney replacement therapy.

Patients diagnosed with glomerulonephritis who

have an appropriate characterisation of their disease

from kidney biopsies and histology; who receive

appropriate therapies and achieve remission are

relieved and are very grateful. Patients are glad to

discontinue dialysis following resolution of acute

kidney injury or acute-on-chronic kidney disease.

Many patients with CKD who have residual

kidney function appreciate being maintained in a

relatively healthy state with conservative measures,

without dialysis. They experience renewed energy

when their anaemia is promptly corrected using

erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. They are happy

when their peripheral oedema resolves with

treatment. For those on maintenance haemodialysis

who had woeful stories from emergency femoral

cannulations, they appreciate the construction of

good temporary or permanent vascular accesses. Many patients in low-resource settings present in

very late stage needing to commence emergency

dialysis. Patients remain grateful for waking from a

uraemic coma or recovering from recurrent seizures

when they commence dialysis.

World kidney day 2021 advocacy

World Kidney Day 2021 theme on ‘Living Well with

Kidney Disease’ is deliberately chosen to have the

goals to redirect more focus on plans and actions

towards achieving patient-centred wellness. “Kidney

Health for Everyone, Everywhere” with emphasis

on patient-centred wellness should be a policy

imperative that can be successfully achieved if policy

makers, nephrologists, healthcare professionals,

patients, and care partners place this within the

context of comprehensive care. The requirement

of patient engagement is needed. The WHO in

2016 put out an important document on patient

empowerment

15:

“Patient engagement is increasingly recognised

as an integral part of healthcare and a critical

component of safe people-centred services. Engaged

patients are better able to make informed decisions

about their care options. In addition, resources may be

better used if they are aligned with patients’ priorities

and this is critical for the sustainability of health

systems worldwide. Patient engagement may also

promote mutual accountability and understanding

between patients and healthcare providers. Informed

patients are more likely to feel confident to report both

positive and negative experiences and have increased

concordance with mutually agreed care management

plans. This not only improves health outcomes but

also advances learning and improvement while

reducing adverse events.”

In the International Society of Nephrology

Community Film Event at World Congress of

Nephrology 2020, it is good to see a quote in the film

from patients:

“Tell me. I will forget; Show me. I will remember; Involve me. I will understand.”

The International Society of Nephrology

Global Kidney Policy Forum 2019 included a patient

speaker Nicki Scholes-Robertson from New Zealand:

“Culturally appropriate and sensitive patient

information and care are being undertaken in New

Zealand to fight inequities in kidney health, especially

in Maori and other disadvantaged communities.”

World Kidney Day 2021 would like to promote

to the policy makers on increasing focus and

resources on both drug and non-drug programmes

in improving patient wellness. Examples include

funding for erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and

antipruritic agents for managing anaemia and

itchiness, respectively, just name but a few.

16 17 Home

dialysis therapies have been consistently found to

improve patient autonomy and flexibility, quality of life in a cost-effective manner, enhancing life

participation. Promoting home dialysis therapies

should tie in with appropriate ‘assisted dialysis’

programmes to reduce patient and care partner

fatigue and burnout. Also, examples like self-management

programmes, cognitive behavioural

therapy, and group therapies for managing

depression, anxiety, and insomnia should be

promoted before resorting to medications.

18 The

principle of equity recognises that different people

with different levels of disadvantage require different

approaches and resources to achieve equitable

health outcomes. The kidney community should

push for adapted care guidelines for vulnerable and

disadvantaged populations. The involvement of

primary care and general physicians especially in low

and lower-middle-income countries would be useful

in improving the affordability and access to services

through the public sector in helping the symptom

management of patients with CKD and improve

their wellness. In the overall wellness programme

for kidney disease patients, the need for prevention

should be reiterated. Early detection with a prolonged

course of wellness despite kidney disease, after an

effective secondary prevention programme, should

be promoted.

19 Prevention of CKD progression can

be attempted by lifestyle and diet modifications

such as a plant-dominant low-protein diet and

by means of effective pharmacotherapy including

administration of sodium-glucose transport protein

2 inhibitors.

20 World Kidney Day 2021 continues

to call for increased awareness of the importance

of preventive measures throughout populations,

professionals, and policy makers, applicable to both

developed and developing countries.

19

Conclusions

Effective strategies to empower patients and their

care partners strive to pursue the overarching goal

of minimising the burden of CKD-related symptoms

in order to enhance patient satisfaction, health-related

quality of life, and life participation. World

Kidney Day 2021 theme on ‘Living Well with Kidney

Disease’ is deliberately chosen to have the goals to

redirect more focus on plans and actions towards

achieving patient-centred wellness. Notwithstanding

the COVID-19 pandemic that had overshadowed

many activities in 2020 and beyond, the World

Kidney Day Steering Committee has declared 2021

the year of ‘Living well with Kidney Disease’ in an

effort to increase education and awareness on the

important goal of effective symptom management

and patient empowerment. Whereas the World

Kidney Day continues to emphasise the importance

of effective measures to prevent kidney disease

and its progression,

18 patients with pre-existing

kidney disease and their care partners should feel

supported to live well through concerted efforts by kidney care communities and other stakeholders

throughout the world even during a world-shattering

pandemic as COVID-19 that may drain

many resources.

21 Living well with kidney disease is

an uncompromisable goal of all kidney foundations,

patient groups, and professional societies alike, to

which the International Society of Nephrology and

the International Federation of Kidney Foundation

World Kidney Alliance are committed at all times.

Author contributions

K Kalantar-Zadeh reports honoraria from Abbott, AbbVie,

ACI Clinical, Akebia, Alexion, Amgen, Ardelyx, Astra-Zeneca,

Aveo, BBraun, Cara Therapeutics, Chugai, Cytokinetics,

Daiichi, DaVita, Fresenius, Genentech, Haymarket Media,

Hospira, Kabi, Keryx, Kissei, Novartis, Pfizer, Regulus,

Relypsa, Resverlogix, Dr Schaer, Sandoz, Sanofi, Shire, Vifor,

UpToDate, and ZS-Pharma. PKT Li reports personal fees

from Fibrogen and Astra-Zeneca. G Saadi reports personal

fees from Multicare, Novartis, Sandoz, and Astra-Zeneca.

V Liakopoulos reports non-financial support from Genesis

Pharma. All other authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

This article was published in Kidney International, volume

99, pages 278-284, Copyright World Kidney Day Steering

Committee (2021), and reprinted concurrently in several

journals. The articles cover identical concepts and wording,

but vary in minor stylistic and spelling changes, detail, and

length of manuscript in keeping with each journal’s style. Any

of these versions may be used in citing this article.

References

1. Tong A, Manns B, Wang AY, et al. Implementing core

outcomes in kidney disease: report of the Standardized

Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG) implementation

workshop. Kidney Int 2018;94:1053-68.

Crossref2. Carter SA, Gutman T, Logeman C, et al. Identifying

outcomes important to patients with glomerular disease and

their caregivers. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;15:673-84.

Crossref3. Hanson CS, Craig JC, Logeman C, et al. Establishing core

outcome domains in pediatric kidney disease: report of

the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Children and

Adolescents (SONG-KIDS) consensus workshops. Kidney

Int 2020;98:553-65.

Crossref4. González AM, Gutman T, Lopez-Vargas P, et al. Patient and

caregiver priorities for outcomes in CKD: a multinational

nominal group technique study. Am J Kid Dis 2020;76:679-89.

Crossref5. World Health Organization, The International

Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

Towards a common language for functioning, disability

and health. 2002. Available from: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr

2021.

6. World Health Organization. Health Promotion Glossary. 1998. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HPR-HEP-98.1. Accessed 11 Apr 2021.

7. Baumgart A, Manera KE, Johnson DW, et al. Meaning

of empowerment in peritoneal dialysis: focus groups

with patients and caregivers. Nephrol Dial Transplant

2020;35:1949-58.

Crossref8. PCORI. The Value of Engagement. Available from: https://

www.pcori.org/about-us/our-programs/engagement/public-and-patient-engagement/value-engagement. 2018. Accessed 1 Sep 2020.

9. Bonventre JV, Hurst FP, West M, Wu I, Roy-Chaudhury

P, Sheldon M. A technology roadmap for innovative

approaches to kidney replacement therapies: a catalyst for

change. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;14:1539-47.

Crossref10. Ibrahim N, Michail M, Callaghan P. The strengths based

approach as a service delivery model for severe mental

illness: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. BMC Psychiatry

2014;14:243.

Crossref11. Parham R, Jacyna N, Hothi D, Marks SD, Holttum S, Camic P. Development of a measure of caregiver burden

in paediatric chronic kidney disease: The Paediatric Renal

Caregiver Burden Scale. J Health Psychol 2014;21:93-205.

Crossref12. Subramanian L, Kirk R, Cuttitta T, et al. Remote

management for peritoneal dialysis: a qualitative study

of patient, care partner, and clinician perceptions and

priorities in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Kidney Med 2019;1:354-65.

Crossref13. Angwenyi V, Aantjes C, Kajumi M, De Man J, Criel B,

Bunders-Aelen J. Patients experiences of self-management

and strategies for dealing with chronic conditions in rural

Malawi. PLoS One 2018;13:e0199977.

Crossref14. Ulasi II, Ijoma CK. The enormity of chronic kidney disease

in Nigeria: the situation in a teaching hospital in South-East Nigeria. J Trop Med 2010;2010:501957.

Crossref15. World Health Organization. Patient engagement. Available

from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252269.

Accessed 11 Apr 2021.

16. Spinowitz B, Pecoits-Filho R, Winkelmayer WC, et al.

Economic and quality of life burden of anemia on patients

with CKD on dialysis: a systematic review. J Med Econ

2019;22:593-604.

Crossref17. Sukul N, Speyer E, Tu C, et al. Pruritus and patient reported

outcomes in non-dialysis CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol

2019;14:673-81.

Crossref18. Gregg LP, Hedayati SS. Pharmacologic and psychological

interventions for depression treatment in patients with

kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2020;29:457-64.

Crossref19. Li PK, Garcia-Garcia G, Lui SF, et al. Kidney health for

everyone everywhere—from prevention to detection and

equitable access to care. Kidney Int 2020;97:226-32.

Crossref20. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Li PK. Strategies to prevent kidney

disease and its progression. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020;16:129-30.

Crossref21. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Wightman A, Liao S. Ensuring choice

for people with kidney failure—dialysis, supportive care,

and hope. N Engl J Med 2020;383:99-101.

Crossref