EDITORIAL

Importance of surveillance and vaccination in

managing respiratory syncytial virus infections among older adults in Hong Kong

Jane CK Chan, MD (UChicago), DABIM1; Mike YW Kwan, MSc, MRCPCH1,2; Wilson Lam, FRCP (Edin), FHKAM (Medicine)3; Christopher KC Lai, FRCPath (UK), FHKAM (Pathology)4,5; Grant Waterer, FRACP, FCCP6; Anna Cheng, FHKAM (Paediatrics), MPH (CUHK)7; Maureen Wong, FHKAM (Medicine)8; KM Sin, FHKAM (Medicine)9; Ken KP Chan, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP (Glasg)10,11; Angus Lo, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP (Edin)12; Macy MS Lui, MD, FHKAM (Medicine)13; WS Leung, FHKAM (Medicine)14; Martin CS Wong, MD, MPH15,16

1 Hong Kong Chinese Medical Association Ltd, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Hong Kong Hospital Authority Infectious Disease Centre, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Specialist in Infectious Disease, Private Practice, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 SH Ho Research Centre for Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 Royal Perth Hospital, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia

7 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

8 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

9 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

10 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

11 Li Ka Shing Institute of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

12 Specialist in Respiratory Medicine, Private Practice, Hong Kong SAR, China

13 Division of Respiratory Medicine, Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

14 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

15 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

16 Editor-in-Chief, Hong Kong Medical Journal

Full paper in PDF

Full paper in PDF

Respiratory syncytial virus: an

underrecognised and evolving public health threat

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a common

cause of respiratory infections globally and in Hong

Kong.

1 2 It is the leading cause of hospitalisation due

to respiratory viral infections among infants and

young children, and it is increasingly recognised

as a substantial threat to older adults.

1 2 3 4 Although

hospitalised at lower rates than infants and young

children, older people are more likely to experience

severe outcomes, including cognitive decline,

infection-triggered acute myocardial infarction,

stroke, or even death.

1 2 3 4 Contemporary data

suggest that the spread and consequences of RSV,

particularly in older adults, have consistently been

underestimated.

1 2 4 In older adults, the clinical

outcomes of RSV infection are comparable to, or

even more severe than, those of influenza.

2 3 In Hong

Kong, large-scale epidemiological data on RSV are

currently unavailable.

Both upper respiratory tract and lower

respiratory tract (LRT) specimens may be used to test for RSV. In a previous local study reviewing multiplex

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results from 20 127

respiratory specimens tested in a hospital across

all age-groups between 2014 and 2023, RSV was

detected in 2.03% of LRT specimens (including sputa

and endotracheal/tracheal/bronchial aspirates)

and in 7.93% of upper respiratory tract specimens

(combined nasal/nasopharyngeal and throat swabs).

5

In a multicentre, prospective study recruiting

adult patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease and infective exacerbations, a higher RSV

positivity rate by quantitative PCR was observed

in sputum samples compared with nasopharyngeal

swabs (7.69% vs 2.02%, respectively).

6 Given that

there is no single RSV test in adults with acceptable

diagnostic accuracy, these figures may represent

underestimates.

6 In this study, 59% of RSV-associated

exacerbations were PCR-negative, despite sample

collection within 5 days of symptom onset.

6

Local studies have demonstrated substantial

morbidity and mortality associated with RSV

infections among older adults. A small study found

that, of 71 older adults (median age: 75 years; 74%

with co-morbidities) hospitalised with RSV, 61% required supplemental oxygen, and 18% had severe

disease requiring non-invasive ventilation or

intensive care, or resulting in death within 30 days.

7

Furthermore, in a retrospective study of adults

admitted between 2009 and 2011 to three acute care

general hospitals in Hong Kong serving a population

of over 1.5 million, 607 patients (mean age: 75 years)

had virologically confirmed RSV infection; 30-and 60-day mortality rates were 9.1% and 11.9%,

respectively.

3 Finally, in a study of hospitalised

patients with laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus

infections between 1998 and 2012, the incidence

of hospitalisation due to RSV was 2.09 per 10 000

population in both men and women aged 65 to 74

years. The mean annual mortality in this age-group

was 17.44 per 1 000 000 population for men and

11.02 per 1 000 000 population for women.

1

A disruption in the population genetic diversity

and seasonality of RSV as a consequence of the

COVID-19 pandemic has been observed.

8 9 10

Australian data demonstrated that many historically

detected RSV lineages were no longer circulating

after 2021, having been superseded by two novel

RSV-A lineages, which may become dominant due

to their greater resilience, fitness, infectivity, or a

combination of these factors.

8 Additionally, the RSV

Hospitalization Surveillance Network in the US has shown that COVID-19 affected RSV

seasonality, with a shorter but more intense season of

infection in 2022-2023, though with at least a trend

towards pre-COVID norms in the 2023-2024 season.

9

Although surveillance for RSV in Hong Kong

is comparatively less extensive, data from the local

health authority suggest that the post-COVID

pattern of RSV has also changed; it may now comprise

a single infective season peaking between April

and October.

10 Moreover, a recent local paediatric

study showed significantly increased odds of RSV

infection in children aged 3 years or above after the

COVID-19 lockdown, although the full impact

remains to be determined.

11

In addition to the evolving pathogenicity of

RSV infection following the COVID-19 pandemic,

it is important to note the increasingly ageing

population and, consequently, a growing vulnerable

population in regions such as Hong Kong, which

will inevitably contribute to a heavier RSV disease

burden.

12 Accordingly, it is crucial to conduct

adequate surveillance to monitor the changing

epidemiology and to inform appropriate risk

mitigation strategies.

Along with increased surveillance, the

recent introduction of vaccines against RSV (from

2023 onwards) has created a new opportunity to

manage the risk of infection and its consequences.

13

Internationally, vaccination against RSV has

been recommended by national or supranational

organisations in multiple locations; older age is recognised as an independent risk factor, alongside

various cardiopulmonary, metabolic, and immune

conditions (

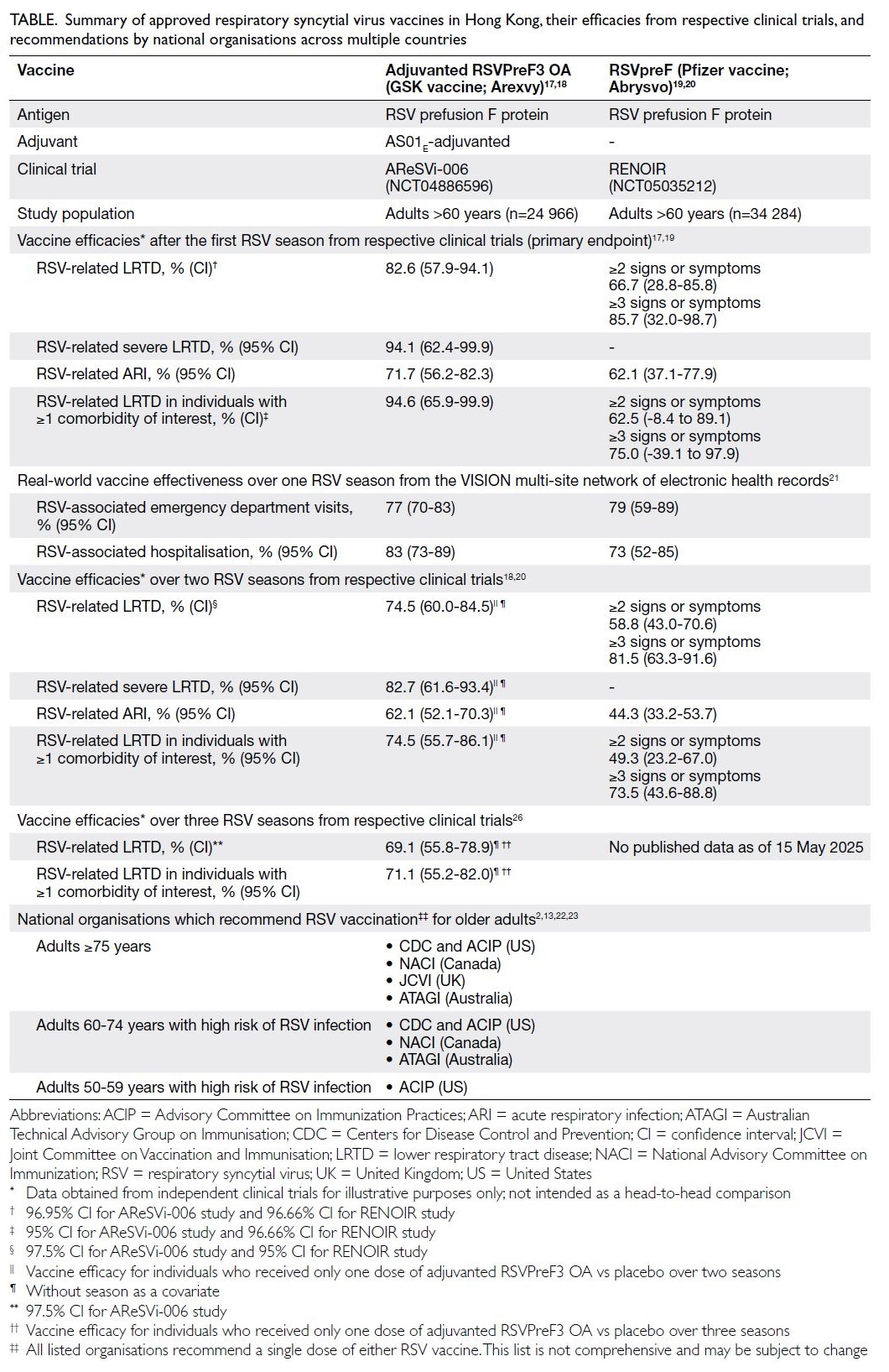

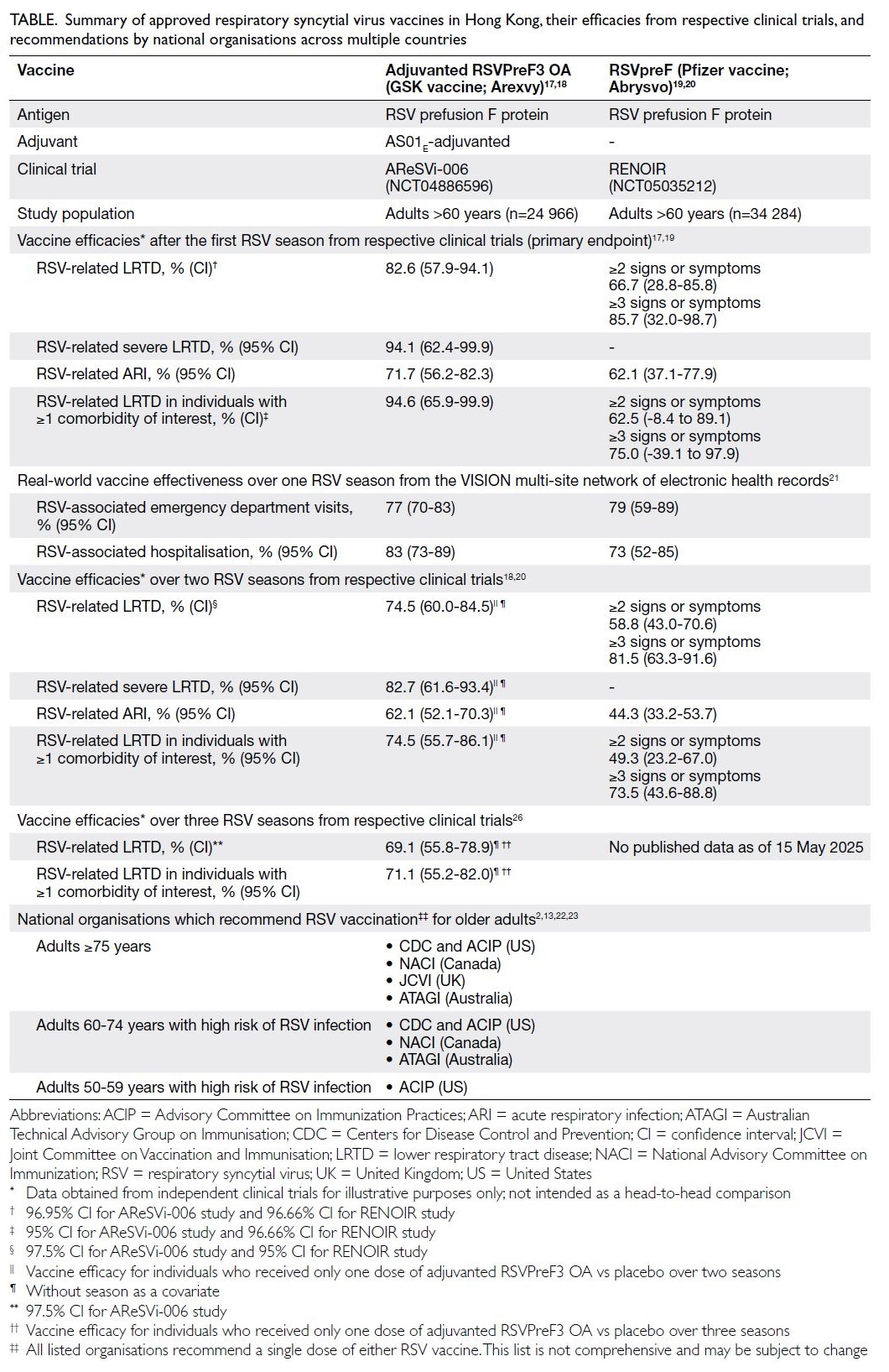

Table).

2 13 Understanding the extent of

risk for the local population in Hong Kong, as well as

the effectiveness of targeted interventions (eg, vaccine

rollout), will rely on analyses of epidemiological data.

Table.

Table. Summary of approved respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in Hong Kong, their efficacies from respective clinical trials, and recommendations by national organisations across multiple countries

Respiratory syncytial virus surveillance: international approaches and implications for Hong Kong

Globally, approaches to RSV surveillance vary

considerably. In Australia and South Korea, RSV

is actively monitored as a notifiable disease, and

healthcare professionals (HCPs) are mandated to

report all confirmed cases to a central source.

14 15

Active surveillance promotes testing for RSV, while

its status as a notifiable disease facilitates systematic

data collection, which, upon analysis, can effectively

support the formulation of health strategies, their

implementation, and informed health policy

decision making.

Given that RSV is not a notifiable disease,

its surveillance in Hong Kong is primarily

conducted through sentinel clinics and a limited

number of public and private hospitals. Sentinel

systems generally require relatively low resource

consumption but may not cover a sufficiently large

population to provide accurate estimates of virus

circulation. The impetus to test for RSV may also

be limited in patients presenting with non-severe

respiratory illnesses, which are common, exhibit

non-specific symptoms, and are typically managed

in a similar manner regardless of aetiology.

15 Thus,

where most sentinel activity occurs in primary care

or community settings, the true burden may be

underrepresented and skewed towards less severe

cases. In contrast, sentinel systems in hospital

settings can yield more detailed information on

severe cases and outcome data concerning the

most serious consequences of infection.

15 In Hong

Kong, RSV is likely underdiagnosed, partly due to

low testing rates in adults, and partly due to skewed

reporting by the existing sentinel system.

To enhance the RSV testing rate, educational

campaigns for HCPs should be implemented to

increase clinical suspicion of RSV in adults and

to raise awareness of its potential consequences

in older adults and other high-risk populations

(eg, those with chronic respiratory, cardiac,

endocrine, or renal diseases, as well as those with

immunodeficiency).

12 13 Targeted surveillance in

these patient groups may offer cost savings. Testing

sites can also be prioritised in areas of greatest risk,

assessing the penetration and spread of RSV among

populations such as older adults residing in higher-density

settings, including long-term care facilities.

To mitigate the resource and workload

implications of increased testing, European and

other international guidelines have recommended

incorporating RSV into existing surveillance systems

for respiratory infections.

15 16 Furthermore, it is

important to standardise the testing method

5 12 15;

PCR remains the preferred tool for confirming

RSV cases, given the risk of false-negative results

with current rapid antigen tests. Hospital-based

surveillance, covering nasopharyngeal specimens

and beyond, may be considered, particularly to

address the potential underdiagnosis of severe RSV

cases.

Practical considerations for enhancing RSV

surveillance in Hong Kong may include integration

with broader respiratory pathogen surveillance and

diagnostic systems, such as those for COVID-19

and influenza.

15 Moreover, it is essential to centralise

procedures, standardise case definitions, and expand

laboratory capacity to streamline the implementation

of territory-wide surveillance.

15

Respiratory syncytial virus

vaccines: efforts for prioritisation

At present, the management of severe RSV infection

is non-specific and largely supportive.

2 Although

this approach may discourage testing or screening

in patients presenting with symptomatic infections,

increased quantity and quality of surveillance data

could be used to optimise an RSV vaccination

campaign. For example, such optimisation could

involve prioritisation of high-risk groups, setting

an appropriate age threshold for vaccination,

and determining the overall cost-benefit ratio for

reducing healthcare resource utilisation under

various vaccination coverage scenarios.

To date, two of the three internationally

licensed RSV vaccines are available in Hong Kong:

the adjuvanted RSVPreF3 OA (Arexvy, GSK)

and RSVpreF (Abrysvo, Pfizer) [

Table].

17 18 19 20 These

vaccines have been evaluated using similar study

designs, although variations exist in the trial centres’

coverage of RSV ‘season’ periods and in the case

definitions used for acute respiratory illness, LRT

illness, and severe LRT illness across at least two RSV

seasons.

18 19 20 Both trials have shown high efficacy and

safety of the respective vaccines against symptomatic

infection and severe outcomes (

Table).

18 20 However,

head-to-head comparisons between the vaccines are

not yet available.

Recent data from the US Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention support the real-world

effectiveness of both RSV vaccines.

21 Based on

findings from the VISION multi-site network of

electronic health records (between 1 October

2023 and 31 March 2024), the effectiveness of

the adjuvanted RSVPreF3 OA vaccine against

RSV-associated emergency department visits and hospitalisations was 77% and 83%, respectively,

among adults aged 60 years or above (

Table).

21

Similarly, RSVpreF demonstrated effectiveness of

79% against emergency department visits and 73%

against hospitalisations.

21

The primary concerns regarding RSV

vaccination are similar to those associated with

other vaccines: how to enhance uptake, raise

awareness, address misconceptions, and identify

which populations should be prioritised for free

or subsidised vaccination through public health

programmes.

12 15 Unresolved scientific questions—such as the duration of protection and the appropriate

age for vaccine administration—continue to be

investigated and can be informed by local data. The

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

recommends RSV vaccination for adults aged 75

years or above, and for those aged 60 to 74 years

with certain chronic medical conditions or other

risk factors (eg, communal living) for severe RSV

infection (

Table).

22 On 16 April 2025, the Advisory

Committee on Immunization Practices extended

this recommendation to adults aged 50 to 59 years

who are at increased risk of severe RSV infection,

following the US Food and Drug Administration’s

licensure of the vaccine for this population group

(

Table).

23

Although RSV vaccines are generally well

tolerated, there have been reports of Guillain—Barré syndrome (GBS) and acute disseminated

encephalomyelitis following vaccination.

24 25

Assessment of GBS risk after vaccination with

RSVpreF and adjuvanted RSVPreF3 OA was

conducted in a self-controlled case series analysis,

using risk windows defined as 1 to 42 days post-vaccination

and control windows as 43 to 90 days

post-vaccination.

25 The analysis of all GBS cases from

this study suggests an increased risk within the first

42 days post-vaccination, equating to seven excess

cases per million doses of adjuvanted RSVPreF3 OA

and nine excess cases per million doses of RSVpreF,

in adults aged 65 years or above.

24 25 While the

findings indicate an increased GBS risk, they are

not sufficient to establish a causal relationship.

25 In

the RENOIR study, one case each of GBS and Miller

Fisher syndrome (a GBS variant) was reported

after RSVpreF vaccination,

19 whereas no cases of

GBS have been reported to date in the AReSVi-006

study investigating the adjuvanted RSVPreF3 OA

vaccine.

17 Nonetheless, both vaccines are required to

include a GBS warning, as mandated by the US Food

and Drug Administration.

25

Respiratory syncytial virus

vaccination in Hong Kong

Collectively, international experience suggests that

the commercial availability of RSV vaccines will

deliver clinical and public health benefits by reducing severe infections and the utilisation of healthcare resources.

In Hong Kong, the adjuvanted RSVPreF3

OA vaccine is indicated for active immunisation to

prevent LRT disease caused by RSV in adults aged 60

years or above, as well as in adults aged 50 to 59 years

who are at increased risk of RSV disease. RSVpreF

is indicated for active immunisation in individuals

aged 60 years or above to prevent LRT disease caused

by RSV. To promote uptake of privately purchased

(self-paid) vaccines, health education initiatives and

advertising campaigns highlighting the importance

of RSV vaccination should be encouraged.

As of January 2025, due to the lack of cost-benefit

studies in older adults, the Hong Kong

Scientific Committee on Vaccine Preventable

Diseases does not universally recommend RSV

vaccination. Instead, the Committee has advised

that vaccination should be considered, particularly

for individuals aged 75 years or above and those

residing in nursing homes.

24 Given that hospitalised

patients with RSV infection frequently present

with co-morbidities (>70% based on available

local data),

3 7 it is suggested that vaccination be

prioritised for all adults aged 75 years or above,

immunocompromised individuals, adults aged 60

years or above with relevant co-morbid conditions

(eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma,

congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease,

cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic

kidney disease, or frailty), and those living in

community housing or residential care settings—concordant with recommendations from the

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

13

Vaccination subsidies should be considered for at-risk

groups who are economically disadvantaged. The

precise target groups, as well as the potential health

and cost savings from a targeted vaccine rollout, will

depend on local epidemiological data. However, the

development of formal recommendations should be

prioritised by the government and relevant medical

societies involved in the care of at-risk populations.

Conclusion

Respiratory syncytial virus infection is not only a

childhood disease; it also poses a major health risk

to older adults, especially those with underlying

morbidities who require targeted prevention and

treatment. The ageing population in Hong Kong

further exacerbates this challenge. The recent

development of effective vaccines (

Table)

17 18 19 20 26

underscores the urgent need to develop up-to-date

recommendations and policies to guide

the rational use of vaccination, both to prevent

severe RSV infection and to reduce the associated

healthcare utilisation and societal costs. The precise

determination of target groups should be informed

by local epidemiological data, which can be generated through dedicated studies and enhanced

RSV surveillance, particularly in hospital settings.

In the interim, HCPs are encouraged to proactively

raise awareness of RSV among both medical peers

and the public, and to consider extending vaccination

to at-risk groups in line with international guidance

and published literature. These combined efforts will

promote a coherent policy of systematic vaccination,

achieving the greatest benefit for patients and the

broader community. Future studies should address

the cost-effectiveness of RSV vaccination across

various at-risk populations.

12 27

Author contributions

Concept or design: JCK Chan.

Acquisition of data: JCK Chan, MYW Kwan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: JCK Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

MCS Wong is an advisory committee member of Pfizer; an external expert of GlaxoSmithKline Limited; a member of the advisory board of AstraZeneca and has been paid consultancy fees for providing advice on research. Other authors did not receive an honorarium for participating

in the preceding advisory board meeting as declared in the

submitted ICMJE disclosure forms.

Acknowledgement

This editorial incorporates insights from an advisory board

meeting held on 15 July 2024 in Hong Kong, with contributions

from private practitioners Dr Aaron Lai, Dr Leung-cheung

Goh, and Dr Mary Cheng.

Funding/support

Medical writing, editorial, and publication coordination

support were independently funded by GSK in accordance with

the Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines. Editorial

and medical writing support were provided by MediPaper

Medical Communications Ltd. The funders had no role in study

design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript

preparation. Ultimate responsibility for the opinions,

interpretation, and conclusions lies with the authors.

References

1. Chan PK, Tam WW, Lee TC, et al. Hospitalization

incidence, mortality, and seasonality of common

respiratory viruses over a period of 15 years in a developed

subtropical city. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e2024.

Crossref2. Wildenbeest JG, Lowe DM, Standing JF, Butler CC.

Respiratory syncytial virus infections in adults: a narrative

review. Lancet Respir Med 2024;12:822-36.

Crossref3. Lee N, Lui GC, Wong KT, et al. High morbidity and

mortality in adults hospitalized for respiratory syncytial

virus infections. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:1069-77.

Crossref4. Savic M, Penders Y, Shi T, Branche A, Pirçon JY. Respiratory

syncytial virus disease burden in adults aged 60 years and

older in high-income countries: a systematic literature

review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses

2023;17:e13031.

Crossref5. Chan WS, Yau SK, To MY, et al. The seasonality of respiratory viruses in a Hong Kong hospital, 2014-2023. Viruses 2023;15:1820.

Crossref6. Wiseman DJ, Thwaites RS, Ritchie AI, et al. Respiratory

syncytial virus–related community chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease exacerbations and novel diagnostics: a

binational prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care

Med 2024;210:994-1001.

Crossref7. Lui G, Wong CK, Chan M, et al. Host inflammatory

response is the major marker of severe respiratory syncytial

virus infection in older adults. J Infect 2021;83:686-92.

Crossref8. Eden JS, Sikazwe C, Xie R, et al. Off-season RSV epidemics

in Australia after easing of COVID-19 restrictions. Nat

Commun 2022;13:2884.

Crossref9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US

Government. RSV-NET. Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Infection (RSV). 2024. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/php/surveillance/rsv-net.html. Accessed 12 Nov 2024.

10. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Detection of pathogens from

respiratory specimens. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/statistics/data/10/641/642/2274.html. Accessed 12 Nov 2024.

11. Pun JC, Tao KP, Yam SL, et al. Respiratory viral infection

patterns in hospitalised children before and after

COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Viruses 2024;16:1786.

Crossref12. Hung IF, Lin AW, Chan JC, et al. Bridging the gap in the

prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infection among

older adults in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2024;30:196-9.

Crossref13. Britton A, Roper LE, Kotton CN, et al. Use of respiratory

syncytial virus vaccines in adults aged ≥60 years:

updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on

Immunization Practices—United States, 2024. MMWR

Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:696-702.

Crossref14. Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

Laboratory surveillance service for influenza and

respiratory viruses. Available from:

https://www.kdca.go.kr/contents.es?mid=a30328000000#wrap. Accessed 12 Nov 2024.

15. Bont L, Krone M, Harrington L, et al. Respiratory syncytial

virus: time for surveillance across all ages, with a focus on

adults. J Glob Health 2024;14:03008.

Crossref16. Teirlinck AC, Broberg EK, Stuwitz Berg A, et al.

Recommendations for respiratory syncytial virus

surveillance at the national level. Eur Respir J

2021;58:2003766.

Crossref17. Papi A, Ison MG, Langley JM, et al. Respiratory syncytial

virus prefusion F protein vaccine in older adults. N Engl J

Med 2023;388:595-608.

Crossref18. Ison MG, Papi A, Athan E, et al. Efficacy and safety of

respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prefusion F protein

vaccine (RSVPreF3 OA) in older adults over 2 RSV seasons.

Clin Infect Dis 2024;78:1732-44.

Crossref19. Walsh EE, Pérez Marc G, Zareba AM, et al. Efficacy and

safety of a bivalent RSV prefusion F vaccine in older adults.

N Engl J Med 2023;388:1465-77.

Crossref20. Walsh EE, Pérez Marc G, Falsey AR, et al. RENOIR Trial—RSVpreF vaccine efficacy over two seasons. N Engl J Med

2024;391:1459-60.

Crossref21. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory

Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US

Government. Effectiveness of adult respiratory syncytial

virus (RSV) vaccines, 2023-2024. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/acip/downloads/slides-2024-06-26-28/07-RSV-Adult-Surie-508.pdf. Accessed 29 Apr 2025.

23. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory

Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US

Government. Evidence to Recommendations Framework

(EtR): RSV vaccination in adults aged 50-59 years. Available

from:

https://www.cdc.gov/acip/downloads/slides-2025-04-15-16/06-Melgar-Surie-adult-rsv-508.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2025.

24. Scientific Committee on Vaccine Preventable Diseases,

Centre for Health Protection, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Interim consensus on the use of respiratory

syncytial virus vaccines in Hong Kong (as of 17 January

2025). Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/interim_consensus_on_the_use_of_respiratory_syncytial_virus_vaccines_in_hong_kong_jan2025.pdf?f=13. Accessed 28 Jan 2025.

25. Drug Office, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. The United States: FDA requires Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) warning in the prescribing

information for RSV vaccines Abrysvo and Arexvy.

Available from:

https://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/eps/news/showNews/The+United+States%3A+FDA+requires+Guillain-Barr%C3%A9+Syndrome+%28GBS%29+warning+in+the+prescribing+information+for+RSV+Vaccines+Abrysvo+and+Arexvy/consumer/2025-01-08/tc/54792.html. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

26. Ison MG, Papi A, Athan E, et al. Efficacy, safety, and

immunogenicity of the AS01

E-adjuvanted respiratory

syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine (RSVPreF3

OA) in older adults over three respiratory syncytial

virus seasons (AReSVi-006): a multicentre, randomised,

observer-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Respir Med 2025;13:517-29.

Crossref27. Kwan MY, Chong PC, Chua GT, Ho MH, Poon LC.

Maternal vaccination: a promising preventive strategy

to protect infants from respiratory syncytial virus. Hong

Kong Med J 2024;30:264-7.

Crossref