EDITORIAL

Are your kidneys OK? Detect early to protect kidney health

Joseph A Vassalotti, MD, PhD1,2 #; Anna Francis, MD, PhD3 #; Augusto Cesar Soares Dos Santos Jr, MD, PhD4,5; Ricardo Correa-Rotter, MD, PhD6; Dina Abdellatif, MD, PhD7; Li-Li Hsiao, MD, PhD8; Stefanos Roumeliotis, MD, PhD9; Agnes Haris, MD, PhD10; Latha A Kumaraswami, MD, PhD11; Siu-Fai Lui, MD, PhD12 Alessandro Balducci, MD, PhD13; Vassilios Liakopoulos, MD, PhD8; for the World Kidney Day Joint Steering Committee

1 Mount Sinai Hospital, Department of Medicine-Renal Medicine, New York, New York, United States

2 National Kidney Foundation, Inc, New York, New York, United States

3 Queensland Children’s Hospital, Department of Nephrology, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

4 Faculdade Ciencias Medicas de Minas Gerais, Brazil

5 Hospital das Clinicas, Ebserh, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil

6 Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, Mexico City, Mexico

7 Department of Nephrology, Cairo University Hospital, Cairo, Egypt

8 Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, United States

9 Second Department of Nephrology, American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association (AHEPA) University Hospital Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

10 Nephrology Department, Péterfy Hospital, Budapest, Hungary

11 Tamilnad Kidney Research (TANKER) Foundation, Chennai, India

12 Division of Health System, Policy and Management, The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

13 Italian Kidney Foundation, Rome, Italy

# Equal contribution

Full paper in PDF

Full paper in PDF

Abstract

Early identification of kidney disease can protect

kidney health, prevent disease progression and

related complications, reduce cardiovascular risk,

and decrease mortality. We must ask, “Are your

kidneys OK?” by using serum creatinine to estimate

kidney function and urine albumin to assess for

kidney and endothelial damage. Evaluation of the

causes and risk factors for chronic kidney disease

includes testing for diabetes and measuring blood

pressure and body mass index. This World Kidney

Day, we assert that case-finding in high-risk

populations—or even population-level screening—can decrease the global burden of kidney disease. Early-stage chronic kidney disease is asymptomatic,

simple to test for, and recent paradigm-shifting

treatments (eg, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2

inhibitors) dramatically improve outcomes and

strengthen the cost–benefit case for screening or

case-finding programmes. Despite these factors,

numerous barriers exist, including resource

allocation, healthcare funding, infrastructure, and

healthcare professional and public awareness of

kidney disease. Coordinated efforts by major kidney

non-governmental organisations to prioritise the

kidney health agenda for governments—and to align

early detection efforts with existing programmes—will maximise efficiencies.

Introduction

Timely treatment is the primary strategy to protect

kidney health, prevent disease progression and

related complications, reduce cardiovascular

risk, and prevent premature kidney-related and

cardiovascular mortality.

1 2 3 International population

assessments show low awareness and detection

of kidney disease, along with substantial gaps in

treatment.

2 People with kidney failure universally

express a preference for having been diagnosed earlier

in their disease trajectory, which would allow more time for educational, lifestyle, and pharmacological

interventions.

4 Therefore, increasing knowledge and

implementing sustainable solutions for the early

detection of kidney disease to protect kidney health

are public health priorities.

2 3

Epidemiology and complications of kidney

disease

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is prevalent, affecting

10% of the global population—over 700 million

people.5 Nearly 80% of people with CKD live in low-income countries (LICs) and lower-middle-income

countries (LMICs), and approximately one-third of

the known affected population resides in China and

India alone.

5 6 The prevalence of CKD increased by

33% between 1990 and 2017.

5 This rising trend is

driven by population growth, ageing, and the obesity

epidemic, which contribute to higher rates of two

major CKD risk factors: type 2 diabetes mellitus

(T2DM) and hypertension. Additionally, risk factors

beyond cardiometabolic conditions add to the

growing burden of kidney disease. These include

social deprivation, pregnancy-related acute kidney

injury, preterm birth, and escalating environmental

threats such as infections, toxins, climate change,

and air pollution.

5 7 These threats disproportionately

affect people in LICs and LMICs.

8

Undetected and untreated CKD is more likely

to progress to kidney failure and cause premature

morbidity and mortality. Globally, more people

died in 2019 of cardiovascular disease attributed to

reduced kidney function (1.7 million people) than

the number who died of kidney disease alone (1.4

million).

5 Chronic kidney disease is expected to

become the fifth most common cause of years of life

lost by 2040, surpassing T2DM, Alzheimer’s disease,

and road injuries.

9 The rising mortality associated

with kidney disease is particularly remarkable

compared with other non-communicable diseases—such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and

respiratory illness—which are projected to exhibit

declining mortality rates.

8 Even in its early stages,

CKD is associated with multi-system morbidity that

diminishes quality of life. Notably, mild cognitive

impairment is linked to early-stage CKD; early

detection and treatment could slow cognitive

decline and reduce the risk of dementia.

10 Chronic

kidney disease in children has profound additional

consequences, threatening growth and cognitive

development, with lifelong health and quality of life

implications.

11 12 The number of people requiring

kidney failure replacement therapy—dialysis or

transplantation—is anticipated to more than

double from 2010 to 2030, reaching 5.4 million.

13 14

Kidney failure replacement therapy, particularly

haemodialysis, remains unavailable or unaffordable

for many in LICs and LMICs, contributing to

millions of deaths annually. Although LICs and

LMICs comprise 48% of the global population,

they represent only 7% of the treated kidney failure

population.

15

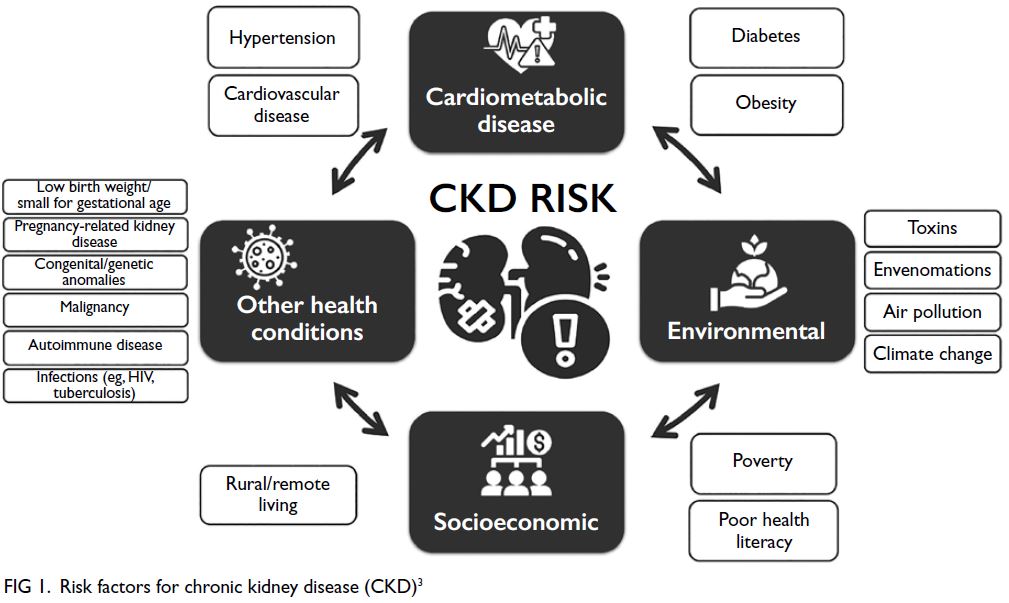

Who is at risk of kidney disease?

Testing individuals at high risk for kidney disease

(case-finding) minimises potential harms and false-positive

results compared with general population

screening, which should only be considered in high-income

countries (HICs). Testing limited to those

at increased risk of CKD would still encompass a large proportion of the global population. Moreover,

targeted case-finding in patients at high risk of

CKD is not optimally performed, even within

HICs. Approximately one in three people globally

have diabetes and/or hypertension. There is a

bidirectional relationship between cardiovascular

disease and CKD—each increases the risk of the

other. Both the American Heart Association and the

European Society of Cardiology recommend testing

individuals with cardiovascular disease for CKD as

part of routine cardiovascular assessments.

1 16

Other CKD risk factors include a family

history of kidney disease (eg, APOL1-mediated

kidney disease, which is common among individuals

of West African ancestry), prior acute kidney injury,

pregnancy-related kidney conditions (eg, pre-eclampsia),

malignancy, autoimmune disorders (such

as systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis),

low birth weight or preterm birth, obstructive

uropathy, recurrent kidney stones, and congenital

anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (

Fig 1).

3

Social determinants of health strongly influence

CKD risk, both at individual and national levels.

In LICs and LMICs, heat stress among agricultural

workers is thought to contribute to CKD of

unknown aetiology—an increasingly recognised and

major global cause of kidney disease.

17 Additionally,

envenomations, environmental toxins, traditional

medicines, and infections (such as hepatitis B or C,

HIV, and parasitic diseases) warrant attention as risk

factors, particularly in endemic regions.

18 19

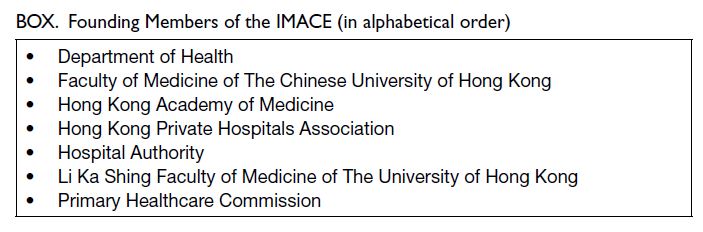

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Risk factors for chronic kidney disease (CKD)

3

How can we check kidney health?

Conceptually, there are three levels of CKD

prevention. Primary prevention aims to reduce

the incidence of CKD by treating risk factors;

secondary prevention focuses on slowing disease

progression and reducing complications in those

with diagnosed CKD; and tertiary prevention

seeks to improve outcomes in people with kidney

failure by enhancing management, such as through

improved vaccination coverage and optimised

dialysis delivery.

20 Primary and secondary prevention

strategies can incorporate the eight golden rules

for promoting kidney health: maintaining a healthy

diet, ensuring adequate hydration, engaging in

physical activity, monitoring and controlling blood

pressure, monitoring and controlling blood glucose

levels, avoiding nicotine, avoiding regular use of

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and targeted

testing for those with risk factors.

21 Five of these

rules are identical to Life’s Essential 8—guidelines

for maintaining cardiovascular health—which also

include achieving a healthy weight, getting adequate

sleep, and managing lipid levels.

22 Early detection

efforts are a form of secondary prevention that

involves protecting kidney health and reducing

cardiovascular risk.

Are your kidneys OK?

Globally, early detection of CKD remains rare,

inconsistent, and less likely in LICs or LMICs.

Currently, only three countries have a national

programme for actively testing at-risk populations

for CKD, and a further 17 countries perform such

testing during routine healthcare encounters.

23 Even in

HICs, albuminuria is not assessed in more than half

of individuals with T2DM and/or hypertension.

24 25 26

Startlingly, a diagnosis of CKD is often absent even

among those with documented reduced kidney

function. A study conducted in HICs showed that

62% to 96% of individuals with laboratory evidence of

CKD stage G3 had no recorded diagnosis of CKD.

27

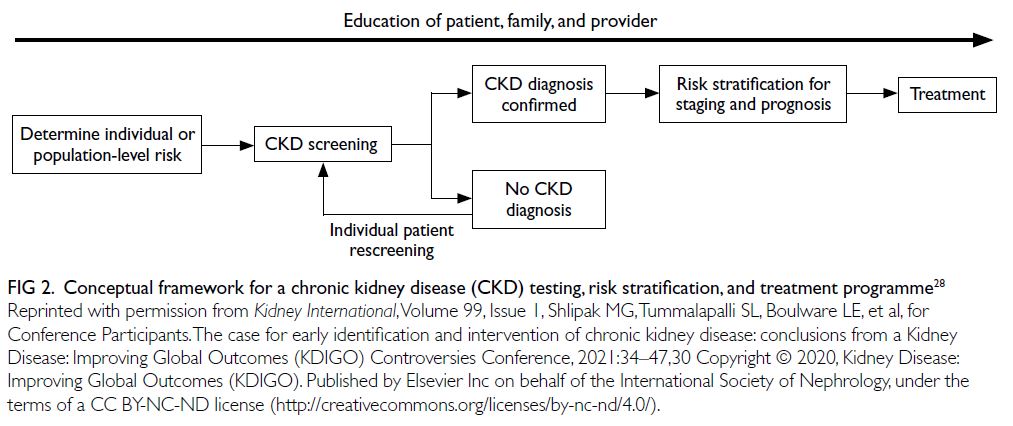

We recommend that healthcare professionals

perform the following tests for all risk groups to

assess kidney health (

Fig 2 28):

a) Blood pressure measurement: Hypertension is

the most prevalent risk factor for kidney disease

worldwide.

3 29 30

b) Body mass index: Obesity is epidemiologically

associated with CKD risk, both indirectly

(via T2DM and hypertension) and directly,

as an independent risk factor. Visceral

adiposity contributes to monocyte-driven

microinflammation and increased

cardiometabolic kidney risk.

3 29 30

c) Testing for diabetes: Assessment with

glycosylated haemoglobin, fasting blood glucose,

or random glucose should be part of kidney

health screening because T2DM is a common

risk factor.

3 29 30

d) Evaluation of kidney function: Serum creatinine

should be used to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in all healthcare settings.

3 Glomerular

filtration rate should be calculated using a

validated, race-free equation appropriate for the

specific country or region and age-group.

3 In

general, eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 is considered

the threshold for CKD in adults and children; a

threshold of <90 mL/min/1.73 m

2 can be regarded

as ‘low’ in children and adolescents over the age

of 2 years.

3 A limitation of creatinine-based eGFR

is its sensitivity to nutritional status and muscle

mass, which can lead to overestimation in states

of malnutrition or frailty.

3 28 Thus, the use of

both serum creatinine and cystatin C provides a

more accurate estimate of eGFR in most clinical

contexts. However, the feasibility of cystatin

C testing is mainly limited to HICs because of

assay availability and cost relative to creatinine

testing.

3 28 31

e) Testing for kidney damage (albuminuria): In both

adults and children, a first morning urine sample

is preferred for assessing albuminuria.

3 In adults,

the quantitative urinary albumin–creatinine ratio

(uACR) is the most sensitive and preferred test.

3

Analytical standardisation of urinary albumin

is currently underway, which should eventually

support global standardisation of uACR testing.

32

In children, both the protein–creatinine ratio

and uACR should be tested to identify tubular

proteinuria.

3 Semiquantitative albuminuria

testing provides flexibility for point-of-care or

home-based testing.

33 To be considered useful,

semiquantitative or qualitative screening tests

should correctly identify >85% of individuals

with a quantitative uACR of ≥30 mg/g.

34 In resource-limited settings, urine dipstick testing

may be used, with a threshold of +2 proteinuria

or greater to reduce false positives and guide

repeat confirmatory testing.

35

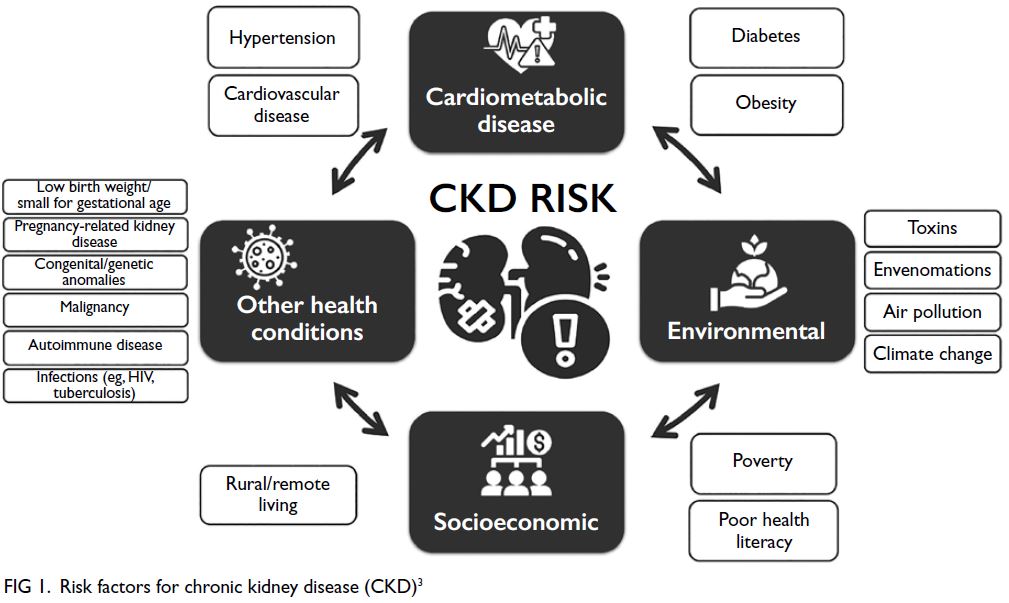

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework for a chronic kidney disease (CKD) testing, risk stratification, and treatment programme

28

In specific populations, the following

considerations may apply:

f) Testing for haematuria: Haematuria is often

overlooked in recent clinical practice guidelines,

despite its importance as a risk factor (particularly

for individuals at risk of glomerular disease, such

as immunoglobulin A nephropathy).

36

g) Baseline imaging: Imaging should be performed

in individuals presenting with signs or symptoms

of structural abnormalities (eg, pain and

haematuria) to identify kidney masses, cysts,

stones, hydronephrosis, or urinary retention.

Antenatal ultrasound can detect hydronephrosis

and other congenital anomalies of the kidney and

urinary tract.

h) Genetic testing: With increasing access to genetic

diagnostics, family cascade testing for CKD is

indicated where there is a known hereditary risk

of kidney disease.

37

i) Occupational health screening: Individuals with

occupational risk of developing kidney disease

should be offered kidney function testing as part

of workplace health programmes.

j) Post-donation surveillance: Kidney donors should

be included in long-term follow-up programmes

to monitor kidney health after donation.

38

Potential benefits of early detection

Screening for CKD aligns well with many

of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s

Wilson–Jungner principles.

39 Early-stage CKD

is asymptomatic; effective interventions—including lifestyle modification, interdisciplinary

care, and pharmacological treatments—are well

established.

2 3 28 35 Several WHO Essential Medicines

that improve CKD outcomes should be widely available, including angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, statins,

and SGLT2is (sodium-glucose co-transporter-2

inhibitors).

2 40 Sodium glucose co-transporter-2

inhibitors alone are estimated to decrease the risk

of CKD progression by 37% in individuals with and

without diabetes.

41 For a 50-year-old individual with

albuminuria and non-diabetic CKD, this treatment

could extend their healthy kidney function period

from 9.6 to 17 years.

42 These essential medicines

slow progression to more advanced CKD stages

and reduce cardiovascular hospitalisations,

offering near-term cost-effectiveness—especially

vital for LICs. Where available and affordable,

the range of paradigm-shifting medications to

slow CKD progression includes glucagon-like

peptide-1 receptor antagonists, non-steroidal

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, endothelin

receptor antagonists, and specific disease-modifying

drugs (eg, complement-inhibitors); these treatments

herald an exciting new era for nephrology.

Considering the substantial healthcare costs

associated with CKD—particularly those related

to hospitalisation and kidney failure—effective

preventive measures offer clear economic benefits

for both HICs and LICs. Chronic kidney disease

imposes enormous financial burdens on individuals,

their families, healthcare systems, and governments

worldwide. In the United States, CKD costs Medicare

over US$85 billion annually.

13 In many HICs and

middle-income countries, 2% to 4% of national

health budgets are allocated to kidney failure care

alone. In Europe, healthcare costs related to CKD

exceed those associated with cancer or diabetes.

43

Reducing the global burden of kidney care would also

yield important environmental benefits, including

reductions in water usage and plastic waste,

especially from dialysis.

44 On an individual level,

CKD costs are frequently catastrophic, particularly

in LICs and LMICs, where the individuals often bear the majority of healthcare expenses. Only 13%

of LICs and 19% of LMICs provide kidney failure

replacement therapy coverage for adults.

15 Each

year, CKD causes an estimated 188 million people

in LICs and LMICs to incur catastrophic healthcare

expenditures.

45

The most widely cited and studied incremental

cost effectiveness ratio threshold for assessing

screening interventions is US$<50 000 per quality-adjusted

life year.

46 When CKD prevalence is high,

population-wide screening strategies may be

considered in HICs.

33 47 For example, in the United

States, a recent Markov simulation model assessed

population-wide CKD screening in adults aged 35

to 75 years with albuminuria. The model included

treatment with SGLT2is, in addition to standard

care with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor

blockers. The analysis indicated that such a screening

approach would be cost-effective.

47 Additionally,

an evaluation of home-based, semiquantitative

albuminuria screening in the general population in

the Netherlands showed that it was cost-effective.

33

Case finding—targeting higher-risk groups for CKD

detection—offers a more efficient and cost-effective

approach than mass or general population screening.

It reduces costs and potential harms while increasing

the true positive rate of screening tests.

3 35 46 An

alternative incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

threshold, proposed by the WHO, suggests using

a benchmark of less than 1 to 3 times the gross

domestic product per capita per quality-adjusted

life year to evaluate cost-effectiveness in LICs and

LMICs.

46 The recommended tests for detecting

kidney disease are low-cost and minimally invasive,

making them feasible across diverse healthcare

settings. Basic tests, such as eGFR and uACR, are

widely available. In contexts where quantitative

testing for proteinuria is unavailable or unaffordable,

the use of urine dipstick testing can substantially

reduce costs.

31

When coupled with effective interventions,

early identification of individuals with kidney

disease would yield benefits for patients, healthcare

systems, governments, and national economies.

45

Health and quality-of-life gains for individuals

would lead to greater productivity—especially for

younger people with more working years ahead—while improving developmental and educational

outcomes in children and young adults. Individuals

would also be less likely to face catastrophic

healthcare expenses. Governments and healthcare

systems would benefit from reduced CKD-related

expenditures and lower cardiovascular disease costs.

Economies would benefit from increased workforce

participation. These benefits are especially crucial

for lower-income countries, where the burden of

CKD is greatest but the capacity to fund kidney care

is most limited.

Challenges and solutions for implementation

Structural barriers to widespread CKD identification

and treatment include high costs, limited test

reliability, and lack of health information systems

to monitor CKD burden. These challenges are

compounded by a lack of relevant government

and healthcare policy, low levels of CKD-related

knowledge and implementation among healthcare

professionals, and limited public awareness of CKD

and low perceived risk among the general population.

Solutions for implementing effective interventions

include integrating CKD identification into existing

screening programmes, educating both the public

and primary care professionals, and leveraging

joint advocacy efforts from non-governmental

organisations to focus health policy agendas

on kidney disease. Any proposed solution must

carefully balance the potential benefits and harms

of screening and case-finding initiatives. Ethical

considerations encompass resource availability

(such as trained healthcare workers and access to

medicines), affordability of testing and treatment,

and the psychological impact of false positives or

negatives, including potential anxiety for patients

and their families.

48

Successful screening and case-finding

programmes require adequate workforce capacity,

robust health information systems, reliable testing

equipment, and equitable access to medical

care, essential medicines, vaccines, and medical

technologies. Primary care plays a pivotal role in

protecting kidney health, particularly in LICs and

LMICs. The limited global nephrology workforce,

with a median prevalence of only 11.8 nephrologists

per million population, and an 80-fold disparity

between LICs and HICs, is inadequate to detect and

manage the vast majority of CKD.

23 As with other

chronic diseases, primary care clinicians and frontline

health workers are essential for the early detection and

management of CKD.

49 Testing must be affordable,

simple, and practical. In resource-limited settings,

point-of-care creatinine testing and urine dipsticks

are especially useful.

31 Educational efforts targeting

primary care clinicians are crucial to integrating CKD

detection into routine clinical practice, despite time

and resource constraints.

50 51 52 Additionally, automated

clinical decision support systems can leverage

electronic health records to identify individuals with

CKD or those at high risk, then prompt clinicians

with appropriate actions (

Fig 228).

Currently, few countries have CKD registries,

limiting the ability to accurately quantify disease

burden and advocate for resources. Knowledge of

the CKD burden is essential for prioritising kidney

health and developing strategies that progressively

expand to encompass the full spectrum of kidney care.

53 A global survey revealed only one-quarter

of countries (41/162) had a national CKD strategy,

and fewer than one-third (48/162) recognised

CKD as a public health priority.

23 Recognition by

the WHO that CKD is a major contributor to non-communicable

disease mortality would be a crucial

step forward. It would help raise awareness, enhance

local surveillance and monitoring, support the

implementation of clinical practice guidelines, and

improve allocation of healthcare resources.

2

Programmes for the early detection of CKD

will require extensive coordination and active

engagement from a wide range of stakeholders,

including governments, healthcare systems,

and insurers. International and national kidney

organisations—such as the International Society

of Nephrology—are already advocating to the

WHO and individual governments for greater

prioritisation of kidney disease. We must continue

this work through collaborative efforts to streamline

the planning and implementation of early detection

programmes. Integration with existing community

interventions (eg, cardiovascular disease prevention

initiatives) in both LICs and HICs can decrease costs

and maximise efficiency by building on established

infrastructures. Such programmes must be adapted

to local contexts and can be delivered in a variety of

settings, including general practice clinics, hospitals,

regional or national healthcare facilities, and rural

outreach initiatives. Depending on local regulations

and available resources, screening and case-finding

can also occur outside conventional medical

environments, for example, in town halls, churches,

or markets. Community volunteers can also assist

with these outreach and screening efforts.

In conjunction with changes in clinical

practice to promote earlier detection of CKD, we

must also focus on increasing public awareness of

kidney disease risk and promoting health education. Such campaigns should be aimed at both the general

public and patients, with the goal of fostering

greater awareness and self-empowerment. General

population awareness of CKD is poor: nine of ten

people with the condition are unaware that they are

affected.

54 Furthermore, kidney disease is missing

from mainstream media. One analysis of lay press

coverage showed that kidney disease was discussed

11 times less frequently than would be expected based

on its actual contribution to mortality.

55 A number

of national and international organisations have

developed public-facing quizzes to help individuals

assess their risk of kidney disease. These initiatives are

supported by regional studies showing that socially

vulnerable patients with hypertension often do not

understand their kidney health risks.

21 56 57 58 Online

and direct education for healthcare professionals

can also help improve consumer health literacy.

Awareness leads to increased patient activation,

engagement, and shared decision-making. However,

education around CKD must be nuanced—balancing

the need for detection and risk stratification with the

importance of informing and empowering, rather

than frightening, individuals about the timing and

extent of potential interventions (

Box).

4 58 Striking

this balance will be critical for optimising self-efficacy

and encouraging active involvement from

patients, families and caregivers.

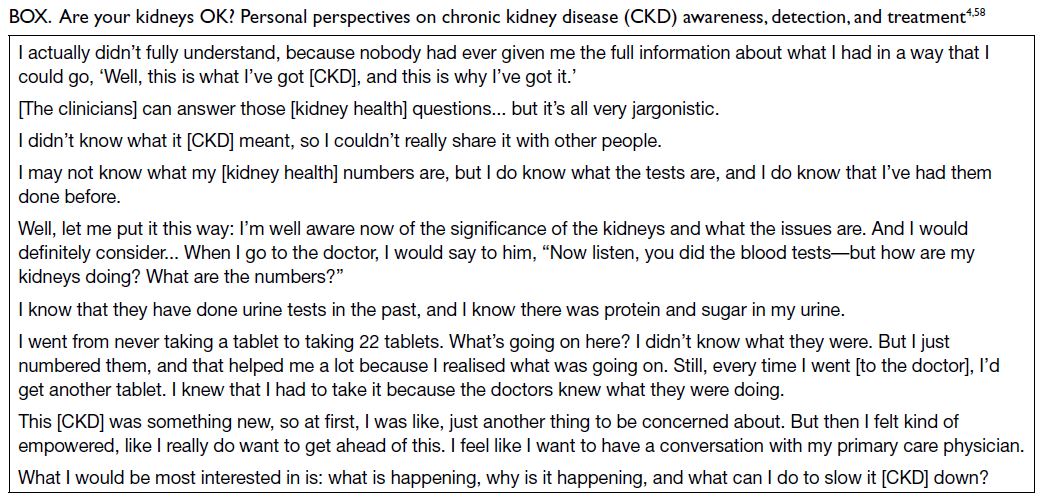

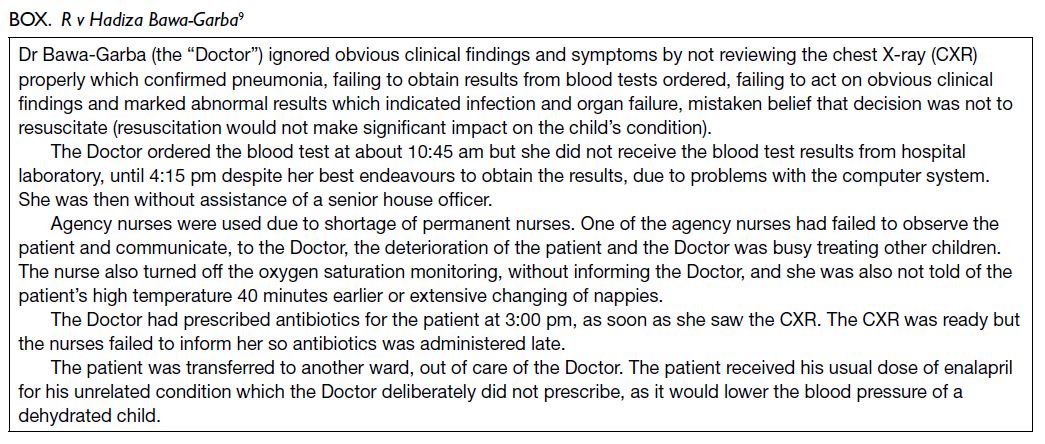

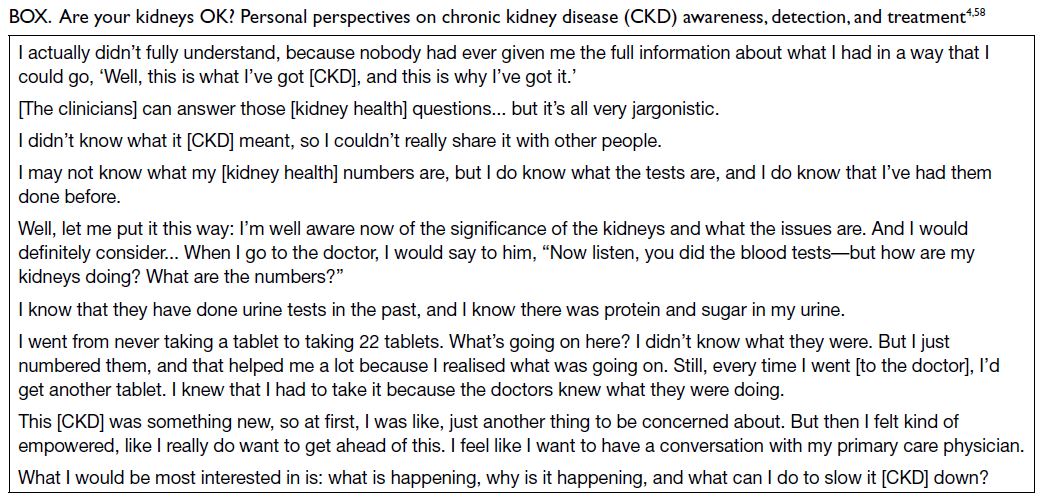

Box.

Box. Are your kidneys OK? Personal perspectives on chronic kidney disease (CKD) awareness, detection, and treatment

4 58

Conclusion: a call to action

We call on all healthcare professionals to assess

the kidney health of patients at risk of CKD.

Concurrently, we must partner with public health

organisations to raise awareness among the general

population about the risk of kidney disease and

empower at-risk individuals to proactively seek

kidney health checks. To make meaningful progress,

collaboration with healthcare systems, governments,

and the WHO is essential to prioritise kidney disease and develop effective, efficient early detection

programmes. Only through these efforts can we

ensure that the paradigm-shifting benefits of lifestyle

changes and pharmacological treatments are fully

realised, leading to better kidney and overall health

outcomes for people around the world.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception, preparation,

and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final

version for publication and take responsibility for its accuracy

and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank members of the World Kidney Day Joint

Steering Committee, including Valerie A Luyckx, Marcello

Tonelli, Ifeoma Ulasi, Vivekanand Jha, Marina Wainstein,

Siddiq Anwar, Daniel O’Hara, Elliot K Tannor, Jorge Cerda,

Elena Cervantes, and María Carlota González Bedat, for their

invaluable feedback on this article.

Declaration

This article was published in Kidney International

(Vassalotti JA, Francis A, Soares Dos Santos AC Jr, et al.

Are your kidneys Ok? Detect early to protect kidney health.

Kidney International. 2025;107(3):370-377.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2024.12.006) and reprinted concurrently

in several journals. The articles cover identical concepts and

wording, but vary in minor stylistic and spelling changes,

detail, and length of manuscript in keeping with each journal’s

style. Any of these versions may be used in citing this article.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Ndumele CE, Neeland IJ, Tuttle KR, et al. A synopsis of

the evidence for the science and clinical management of

cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome: a

scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

Circulation 2023;148:1636-64.

Crossref2. Luyckx VA, Tuttle KR, Abdellatif D, et al. Mind the gap in

kidney care: translating what we know into what we do.

Kidney Int 2024;105:406-17.

Crossref3. Stevens PE, Ahmed SB, Carrero JJ, et al. KDIGO 2024

Clinical Practice Guideline for the evaluation and

management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int

2024;105:S117-314.

Crossref4. Guha C, Lopez-Vargas P, Ju A, et al. Patient needs

and priorities for patient navigator programmes in

chronic kidney disease: a workshop report. BMJ Open

2020;10:e040617.

Crossref5. GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global,

regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease,

1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of

Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020;395:709-33.

Crossref6. Cojuc-Konigsberg G, Guijosa A, Moscona-Nissan A, et al. Representation of low- and middle-income countries in CKD drug trials: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis

2025;85:55-66.e1.

Crossref7. Hsiao LL, Shah KM, Liew A, et al. Kidney health for

all: preparedness for the unexpected in supporting the

vulnerable. Kidney Int 2023;103:436-43.

Crossref8. Francis A, Harhay MN, Ong AC, et al. Chronic kidney

disease and the global public health agenda: an international

consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol 2024;20:473-85.

Crossref9. Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, et al. Forecasting

life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific

mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and

alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and

territories. Lancet 2018;392:2052-90.

Crossref10. Viggiano D, Wagner CA, Martino G, et al. Mechanisms

of cognitive dysfunction in CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol

2020;16:452-69.

Crossref11. Chen K, Didsbury M, van Zwieten A, et al. Neurocognitive and educational outcomes in children and adolescents with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:387-97.

Crossref12. Francis A, Didsbury MS, van Zwieten A, et al. Quality of life of children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. Arch Dis Child 2019;104:134-40.

Crossref13. United States Renal Data System. 2023 USRDS Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2023.

14. Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet 2015;385:1975-82.

Crossref

15. Bello AK, Levin A, Tonelli M, et al. Assessment of global kidney health care status. JAMA 2017;317:1864-81.

Crossref16. Ortiz A, Wanner C, Gansevoort R; ERA Council. Chronic kidney disease as cardiovascular risk factor in routine clinical practice: a position statement by the Council of the European Renal Association. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023;38:527-31.

Crossref17. Johnson RJ, Wesseling C, Newman LS. Chronic kidney disease of unknown cause in agricultural communities. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1843-52.

Crossref18. McCulloch M, Luyckx VA, Cullis B, et al. Challenges of access to kidney care for children in low-resource settings. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021;17:33-45.

Crossref19. Stanifer JW, Muiru A, Jafar TH, Patel UD. Chronic kidney disease in low- and middle-income countries. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016;31:868-74.

Crossref20. Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Burrows NR, et al. Comprehensive public health strategies for preventing the development, progression, and complications of CKD: report of an expert panel convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:522-35.

Crossref21. Internation Society of Nephrology. World Kidney Day 2025. Available from:

https://www.worldkidneyday.org/about-kidney-health/. Accessed 11 Jan 2025.

22. Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CA, et al. Life's Essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association's Construct of Cardiovascular Health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146:e18-43.

Crossref23. Bello AK, Okpechi IG, Levin A, et al. An update on the global disparities in kidney disease burden and care across world countries and regions. Lancet Glob Health 2024;12:e382-95.

Crossref24. Ferrè S, Storfer-Isser A, Kinderknecht K, et al. Fulfillment and validity of the kidney health evaluation measure for people with diabetes. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2023;7:382-91.

Crossref25. Alfego D, Ennis J, Gillespie B, et al. Chronic kidney disease testing among at-risk adults in the U.S. remains low: real-world evidence from a national laboratory database. Diabetes Care 2021;44:2025-32.

Crossref26. Stempniewicz N, Vassalotti JA, Cuddeback JK, et al. Chronic kidney disease testing among primary care patients with type 2 diabetes across 24 U.S. health care organizations. Diabetes Care 2021;44:2000-9.

Crossref27. Kushner PR, DeMeis J, Stevens P, Gjurovic AM, Malvolti E, Tangri N. Patient and clinician perspectives: to create a better future for chronic kidney disease, we need to talk about our kidneys. Adv Ther 2024;41:1318-24.

Crossref28. Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, et al. The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2021;99:34-47.

Crossref29. Farrell DR, Vassalotti JA. Screening, identifying, and treating chronic kidney disease: why, who, when, how, and what? BMC Nephrol 2024;25:34.

Crossref30. Tuttle KR. CKD screening for better kidney health: why? who? how? when? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2024;39:1537-9.

Crossref31. Tummalapalli SL, Shlipak MG, Damster S, et al. Availability and affordability of kidney health laboratory tests around the globe. Am J Nephrol 2020;51:959-65.

Crossref32. Seegmiller JC, Bachmann LM. Urine albumin measurements in clinical diagnostics. Clin Chem 2024;70:382-91.

Crossref33. van Mil D, Kieneker LM, Heerspink HJ, Gansevoort RT. Screening for chronic kidney disease: change of perspective and novel developments. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2024;33:583-92.

Crossref34. Sacks DB, Arnold M, Bakris GL, et al. Guidelines and recommendations for laboratory analysis in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem 2023;69:808-68.

Crossref35. Tonelli M, Dickinson JA. Early detection of CKD: implications for low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;31:1931-40.

Crossref36. Moreno JA, Martín-Cleary C, Gutiérrez E, et al. Haematuria: the forgotten CKD factor? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:28-34.

Crossref37. Franceschini N, Feldman DL, Berg JS, et al. Advancing genetic testing in kidney diseases: report from a National Kidney Foundation Working Group. Am J Kidney Dis 2024;84:751-66.

Crossref38. Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, et al. Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int 2014;86:162-7.

Crossref39. Wilson JM, Jungner G, World Health Organization. Public

Health Papers. Principles and practice of screening for

disease. World Health Organization, 1968. Available from:

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37650. Accessed 11 Apr 2025.

40. Francis A, Abdul Hafidz MI, Ekrikpo UE, et al. Barriers to accessing essential medicines for kidney disease in low- and lower middle-income countries. Kidney Int 2022;102:969-73.

Crossref41. Baigent C, Emberson J, Haynes R, et al. Impact of diabetes on the effects of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes: collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled trials. Lancet 2022;400:1788-801.

Crossref42. Vart P, Vaduganathan M, Jongs N, et al. Estimated lifetime benefit of combined RAAS and SGLT2 inhibitor therapy in patients with albuminuric CKD without diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2022;17:1754-62.

Crossref43. Vanholder R, Annemans L, Brown E, et al. Reducing the costs of chronic kidney disease while delivering quality health care: a call to action. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:393-409.

Crossref44. Berman-Parks N, Berman-Parks I, Gómez-Ruíz IA, Ardavin-Ituarte JM, Piccoli GB. Combining patient care and environmental protection: a pilot program recycling polyvinyl chloride from automated peritoneal dialysis waste. Kidney Int Rep 2024;9:1908-11.

Crossref45. Essue BM, Laba M, Knaul F, et al. Economic burden of chronic ill health and injuries for households in low- and middle-income countries. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, editors. Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017.

Crossref46. Yeo SC, Wang H, Ang YG, Lim CK, Ooi XY. Cost-effectiveness of screening for chronic kidney disease in the general adult population: a systematic review. Clin Kidney J 2024;17:sfad137.

Crossref47. Cusick MM, Tisdale RL, Chertow GM, Owens DK, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. Population-wide screening for chronic kidney disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med 2023;176:788-97.

Crossref48. Yadla M, John P, Fong VK, Anandh U. Ethical issues related to early screening programs in low resource settings. Kidney Int Rep 2024;9:2315-9.

Crossref49. Szczech LA, Stewart RC, Su HL, et al. Primary care detection of chronic kidney disease in adults with type-2 diabetes: the ADD-CKD Study (awareness, detection and drug therapy in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease). PLoS One 2014;9:e110535.

Crossref50. Vassalotti JA, Centor R, Turner BJ, et al. Practical approach to detection and management of chronic kidney disease for the primary care clinician. Am J Med 2016;129:153-62.e7.

Crossref51. Thavarajah S, Knicely DH, Choi MJ. CKD for primary care practitioners: can we cut to the chase without too many shortcuts? Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67:826-9.

Crossref52. Vassalotti JA, Boucree SC. Integrating CKD into US primary care: bridging the knowledge and implementation gaps. Kidney Int Rep 2022;7:389-96.

Crossref53. Luyckx VA, Moosa MR. Priority setting as an ethical imperative in managing global dialysis access and improving kidney care. Semin Nephrol 2021;41:230-41.

Crossref54. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic

kidney disease in the United States, 2023. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/kidney-disease/php/data-research/index.html. Accessed 11 Jan 2025.

55. Dattani S, Spooner F, Ritchie H, Roser M. Causes of death.

2023. Available from:

https://ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death. Accessed 11 Jan 2025.

56. Boulware LE, Carson KA, Troll MU, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Perceived susceptibility to chronic kidney disease among high-risk patients seen in primary care practices. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:1123-9.

Crossref57. National Kidney Foundation. Kidney Quiz 2024. Available

from:

https://www.kidney.org/kidney-quiz/. Accessed 11 Jan 2025.

Crossref58. Tuot DS, Crowley ST, Katz LA, et al. Usability testing of the kidney score platform to enhance communication about kidney disease in primary care settings: qualitative think-aloud study. JMIR Form Res 2022;6:e40001.

Crossref