Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 10 Dec 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

EDITORIAL

The complementarity of quantitative and

qualitative methods: evaluating educational

activities using mixed methods

HY So, MHPE, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)1; Stanley SC Wong, MD, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)2; Abraham KC Wai, MD, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)3; Albert KM Chan, MHPE, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)4; Benny CP Cheng, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)5

1 Educationist, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Chairman, Scientific Committee, Hong Kong College of Anaesthesiologists, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Chairman, Research Subcommittee, The Jockey Club Institute for Medical Education and Development, Hong Kong Academy of

Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Chairman, Board of Education, Hong Kong College of Anaesthesiologists, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Honorary Director, The Jockey Club Institute for Medical Education and Development, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong

SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr HY So (sohingyu@fellow.hkam.hk)

In a recent position paper,1 the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine (HKAM) recommended that both

HKAM and its Colleges establish mechanisms to

evaluate faculty development programmes using

both quantitative and qualitative methods. This

recommendation underscores the importance

of mixed methods approaches in evaluating

educational activities within postgraduate medical

education (PGME). This editorial builds on our

study of the impact of the conjoint workplace-based

assessment (WBA) workshop, published in this

issue of the Hong Kong Medical Journal,2 to

illustrate the effective application of mixed methods

approaches.

Mixed methods combine quantitative and

qualitative approaches to provide a comprehensive

evaluation.3 In healthcare, experimental research

utilising quantitative methods is more familiar; these

methods are equally relevant in medical education.

Quantitative studies rely on measurable data and

statistical analyses to assess the effectiveness of

interventions in numerical terms, such as the

number of trainees achieving a specific competency

level or improvements in assessment scores.

This approach addresses questions such as ‘How

effective was the workshop in enhancing feedback

skills among trainers?’ or ‘What proportion of

trainees demonstrated improved competency after

implementing WBA?’ Quantitative methods are

particularly valuable for investigating cause-and-effect

relationships.4

For descriptive questions about ongoing

events or explanatory questions about how or

why something occurred, qualitative studies are

often the most suitable approach.4 These studies

enhance understanding by exploring experiences,

behaviours, and attitudes, providing insights that cannot be captured through numerical data alone.

This approach is particularly valuable for examining

complex interventions where contextual factors exert

substantial influence. In such situations, adoption of

the CMO model (Context + Mechanism = Outcome)

can be highly effective.5 Qualitative methods (eg,

interviews, focus groups, and observations) enable

the exploration of participants’ perspectives—what they value in an educational intervention,

the challenges they encounter, and areas requiring

improvement. For example, within the context of the

conjoint WBA workshop, qualitative research can

reveal how trainers and trainees perceive WBA and

feedback, their emotional responses, the barriers

they face in effectively integrating WBA into daily

practice, and the factors that facilitate learning

during the workshop.2 Despite the subjective nature

of qualitative research, quality criteria have been

established to ensure its rigour.6

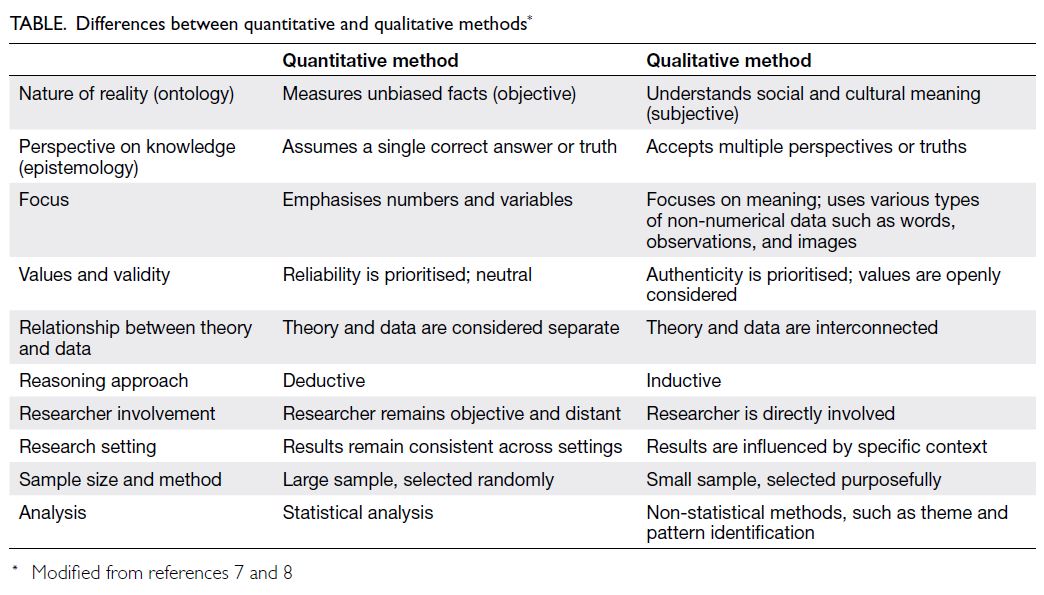

Quantitative and qualitative studies address

distinct research purposes and questions. They

also differ in aspects such as ontology, sampling

methods, and analysis, as summarised in the

Table.7 8 Mixed methods studies combine the

strengths of both approaches, compensating for

the limitations of each. Quantitative data reveal

patterns, whereas qualitative insights provide

essential context and depth, enabling a more

comprehensive understanding. This combination

is particularly important in PGME, where reliance

on quantitative measures alone risks neglecting key

nuances of learner experiences, while qualitative

approaches may lack generalisability. By integrating

both methods, evaluations become more robust

and better suited to inform faculty development,

curriculum enhancement, and improvements to the

clinical learning environment.

Four basic designs for mixed methods studies

are commonly used9:

- Exploratory sequential design: Qualitative research is conducted first to explore a topic, guiding a subsequent quantitative study, often for instrument development.

- Explanatory sequential design: Quantitative data are collected first, followed by qualitative research to explain or provide context to the results.

- Triangulation or convergent design: Qualitative and quantitative data are simultaneously collected to compare and contrast findings.

- Longitudinal transformation: Data are collected at multiple points, typically from different populations and using various methods; analysis and integration occur throughout the project.

In the evaluation of the conjoint WBA

workshop, both triangulation and explanatory

approaches were utilised.2 Quantitative outcomes

demonstrated the success of the intervention.

Qualitative findings not only supported these results

but also explained why specific outcomes were

achieved, guiding future refinements.

However, many clinicians are unfamiliar

with qualitative research methods, which limits

their ability to fully engage with mixed methods

evaluations. To address this limitation, the HKAM

position paper also recommended that training

in qualitative evaluation methods be provided to

Fellows responsible for quality assurance.1 The

Research Subcommittee of the Jockey Club Institute

for Medical Education and Development has

collaborated with the Scientific Committee of the Hong Kong College of Anaesthesiologists to develop

a research course that includes both quantitative and

qualitative methods. This course is now in progress

and may subsequently be offered to other Colleges,

thereby enhancing capacity for quality assurance

across specialties.

As PGME increasingly shifts towards

competency-based approaches, evaluations must

evolve to reflect these changes. Mixed methods

offer a practical means of achieving this evolution,

providing a comprehensive understanding of learner

progress and the contextual factors influencing

outcomes.

The integration of mixed methods into

educational evaluations aligns with HKAM’s vision

of a continuous, evidence-based improvement

cycle in PGME. By uncovering both the ‘what’ and

the ‘why’ behind educational outcomes, educators

become better equipped to make informed decisions

that enhance the learning experience and ultimately

improve the quality of care delivered by future

specialists.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the concept,

development, and critical revision of the manuscript. All

authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

HY So and AKM Chan are co-authors of the article by So et al

(Reference 2), published in the same issue. Other authors have

declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This editorial received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. So HY, Li PK, Lai PB, et al. Hong Kong Academy of Medicine

position paper on postgraduate medical education 2023.

Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:448-52. Crossref

2. So HY, Wong EW, Chan AK, et al. Improving efficiency and

effectiveness of workplace-based assessment workshop in

postgraduate medical education using a conjoint design.

Hong Kong Med J 2025 Dec 9. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

3. Maudsley G. Mixing it but not mixed up: mixed methods

research in medical education (a critical narrative review).

Med Teach 2011;33:e92-104. Crossref

4. Eisenhart M. Qualitative science in experimental time. Int

J Qual Stud Educ 2006;19:697-707. Crossref

5. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA 2008;299:1182-4. Crossref

6. Frambach JM, van der Vleuten CP, Durning SJ. AM last

page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative

research. Acad Med 2013;88:552. Crossref

7. Mehrad A, Zangeneh MH. Comparison between qualitative

and quantitative research approaches: social sciences. Int J

Res Educ Stud 2019;5:1-7.

8. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research: A

Practical Guide for Beginners. Los Angeles: Sage; 2013.

9. Schifferdecker KE, Reed VA. Using mixed methods

research in medical education: basic guidelines for

researchers. Med Educ 2009;43:637-44. Crossref