Improving the emergency department management of post-chemotherapy sepsis in haematological malignancy patients

Hong Kong Med J 2015 Feb;21(1):10–5 | Epub 10 Oct 2014

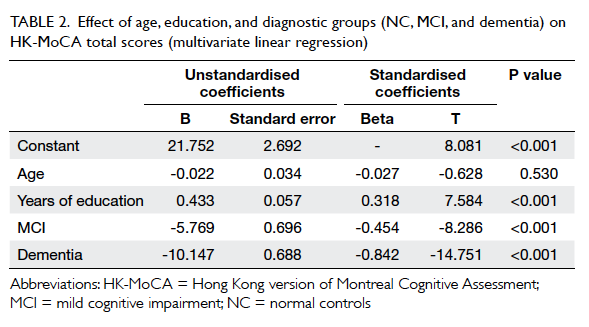

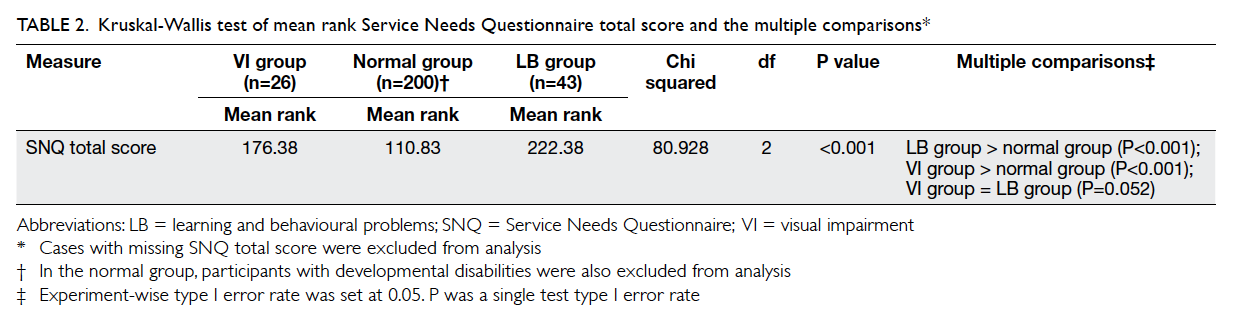

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144280

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Improving the emergency department management of post-chemotherapy sepsis in haematological malignancy patients

HF Ko, MB, BS, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1; SS Tsui, APN1; Johnson WK Tse, APN, BSN HD (Nursing)1; WY Kwong, MB, ChB1; OY Chan, MB, BS2; Gordon CK Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1

1 Accident and Emergency Department, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

2 Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr HF Ko (frankhko@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To review the result of the implementation

of treatment protocol for post-chemotherapy sepsis

in haematological malignancy patients.

Design: Case series with internal comparison.

Setting: Accident and Emergency Department,

Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong.

Patients: Febrile patients presenting to the Accident

and Emergency Department with underlying

haematological malignancy and receiving

chemotherapy within 1 month of Accident and

Emergency Department visit between June 2011 and

July 2012. Similar cases between June 2010 and May

2011 served as historical referents.

Main outcome measures: The compliance rate

among emergency physicians, the door-to-antibiotic

time before and after implementation of the protocol,

and the impact of the protocol on Accident and

Emergency Department and hospital service.

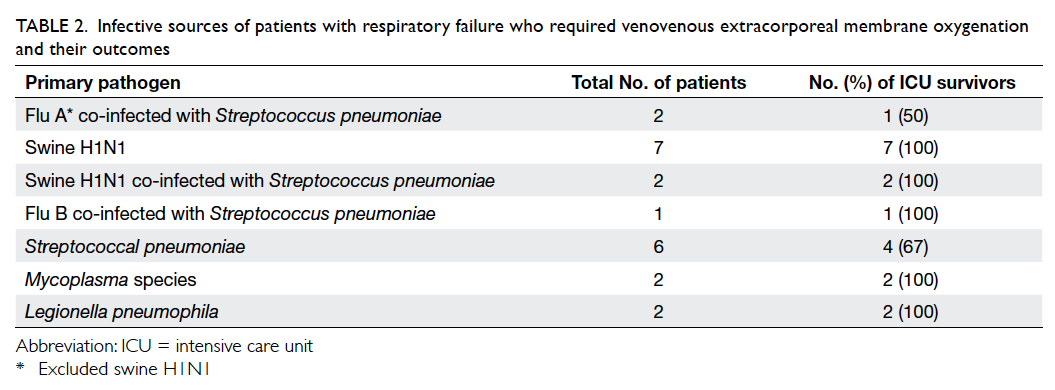

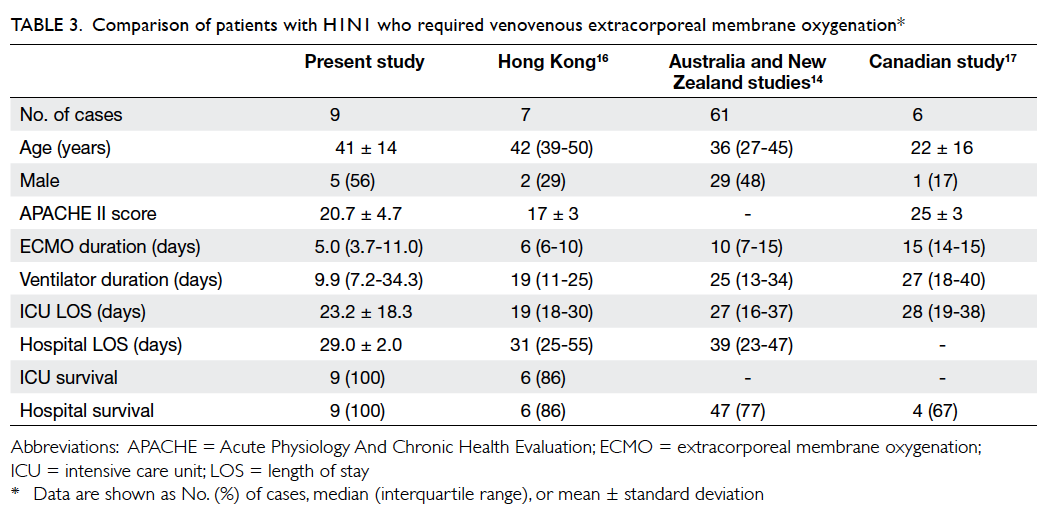

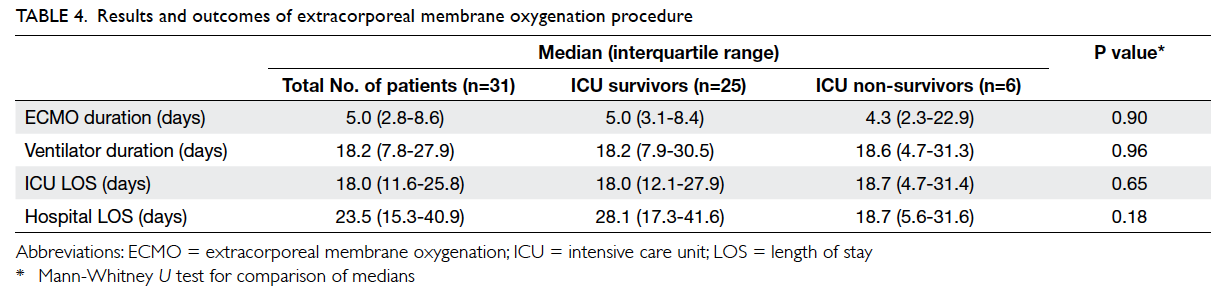

Results: A total of 69 patients were enrolled in

the study. Of these, 50 were managed with the

treatment protocol while 19 patients were historical

referents. Acute myeloid leukaemia was the most

commonly encountered malignancy. Overall, 88%

of the patients presented with sepsis syndrome. The

mean door-to-antibiotic time of those managed

with the treatment protocol was 47 minutes versus

300 minutes in the referent group. Overall, 86% of

patients in the treatment group met the target door-to-antibiotic time of less than 1 hour. The mean

lengths of stay in the emergency department (76 minutes vs

105 minutes) and hospital (11 days vs 15 days) were shorter

in those managed with the treatment protocol versus

the historical referents.

Conclusion: Implementation of the protocol can

effectively shorten the door-to-antibiotic time

to meet the international standard of care in

neutropenic sepsis patients. The compliance rate was

also high. We proved that effective implementation

of the protocol is feasible in a busy emergency

department through excellent teamwork between

nurses, pharmacists, and emergency physicians.

New knowledge added by this

study

- A well-written, easily available treatment protocol together with stocking of antibiotics in the emergency department can effectively shorten the door-to-antibiotic (DTA) time from 300 minutes to 47 minutes.

- In this study, 86% of patients met the target DTA time of less than 1 hour.

- Orchestrated efforts between nurses, pharmacists, and physicians are crucial for implementation of the protocol in one of the busiest emergency departments in the region.

Introduction

Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy sufficient

to cause myelosuppression and adverse effects on

the integrity of gastro-intestinal mucosa are at high

risk of invasive infections. Patients with profound,

prolonged neutropenia are at particularly high risk

of serious infections. Prolonged neutropenia is most

likely to occur in patients undergoing induction

chemotherapy for acute leukaemia. More than 80% of

those with haematological malignancies will develop

fever during more than one chemotherapy cycle.1

Since neutropenic patients are unable to mount a

strong inflammatory response to infections, fever may

be the only sign. Infection in neutropenic patients

can progress rapidly, leading to serious complications

and even death with a mortality rate ranging from

2% to 21%.2 3 It is critical to recognise neutropenic

fever patients early and initiate empirical, broad-spectrum antibiotics. Major international guidelines

advocate early administration of empirical antibiotics

within 1 hour of emergency department (ED)

presentation, sometimes even without cytological

proof of neutropenia.4 5 6 7 However, management of

febrile neutropenic patients varies across different

EDs, and even among different physicians. A recent

audit performed in the EDs of the United Kingdom

showed that only 26% of the audited patients received

intravenous antibiotics within the target time of

1 hour.8 Another study in French EDs showed that

management of febrile neutropenia was inadequate

and severity was under-evaluated in the critically ill.9

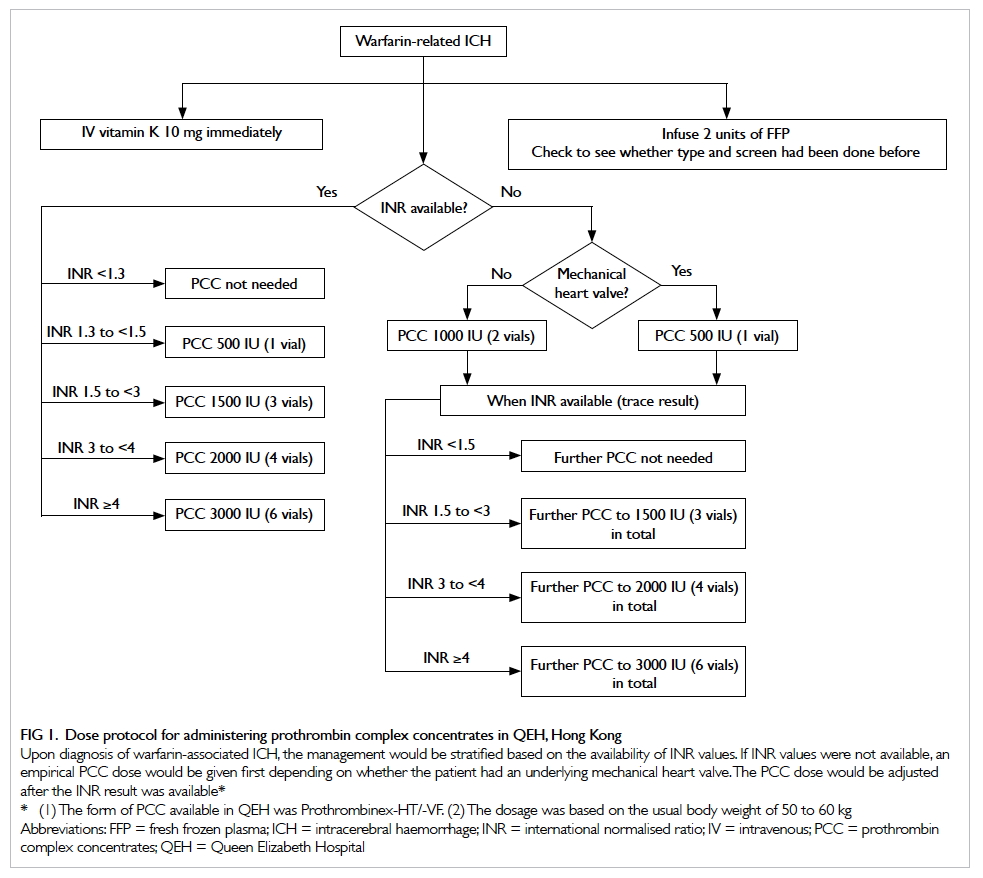

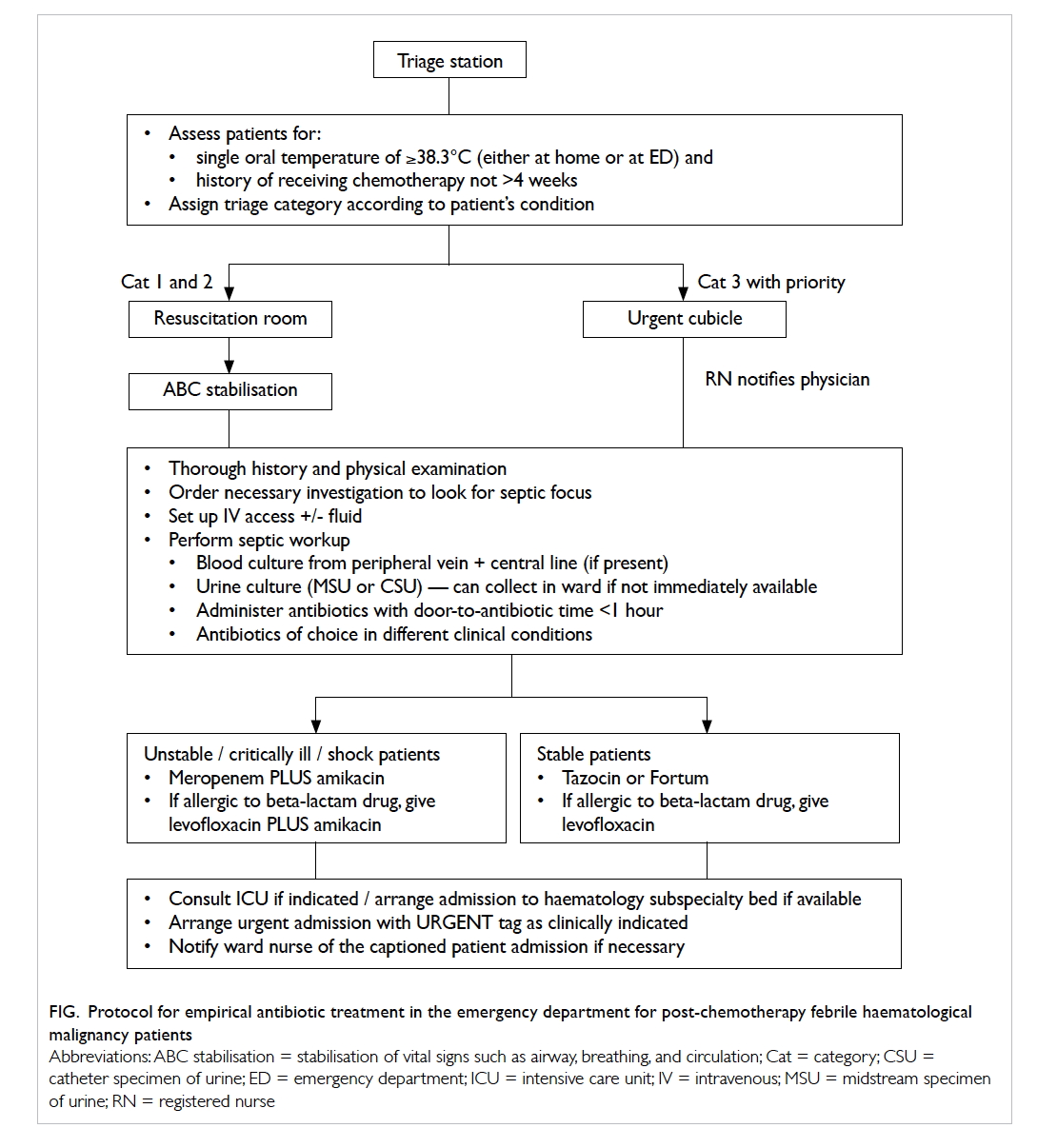

In order to improve and standardise the care of post-chemotherapy

sepsis in haematological malignancy

patients, the Accident and Emergency Department

(A&E) and Department of Medicine of Queen

Elizabeth Hospital (QEH) initiated a treatment

protocol in 2011. This is the first hospital in Hong

Kong to implement such a treatment protocol.

It included febrile patients with haematological

malignancy who had received chemotherapy within

1 month of ED visit. These patients were identified

at triage station and provided with a fast-track

consultation. The ED physician would verify the

history and perform a thorough physical examination

and targeted investigations. Empirical antibiotics

were administered after taking appropriate culture

samples aiming at a door-to-antibiotic (DTA) time

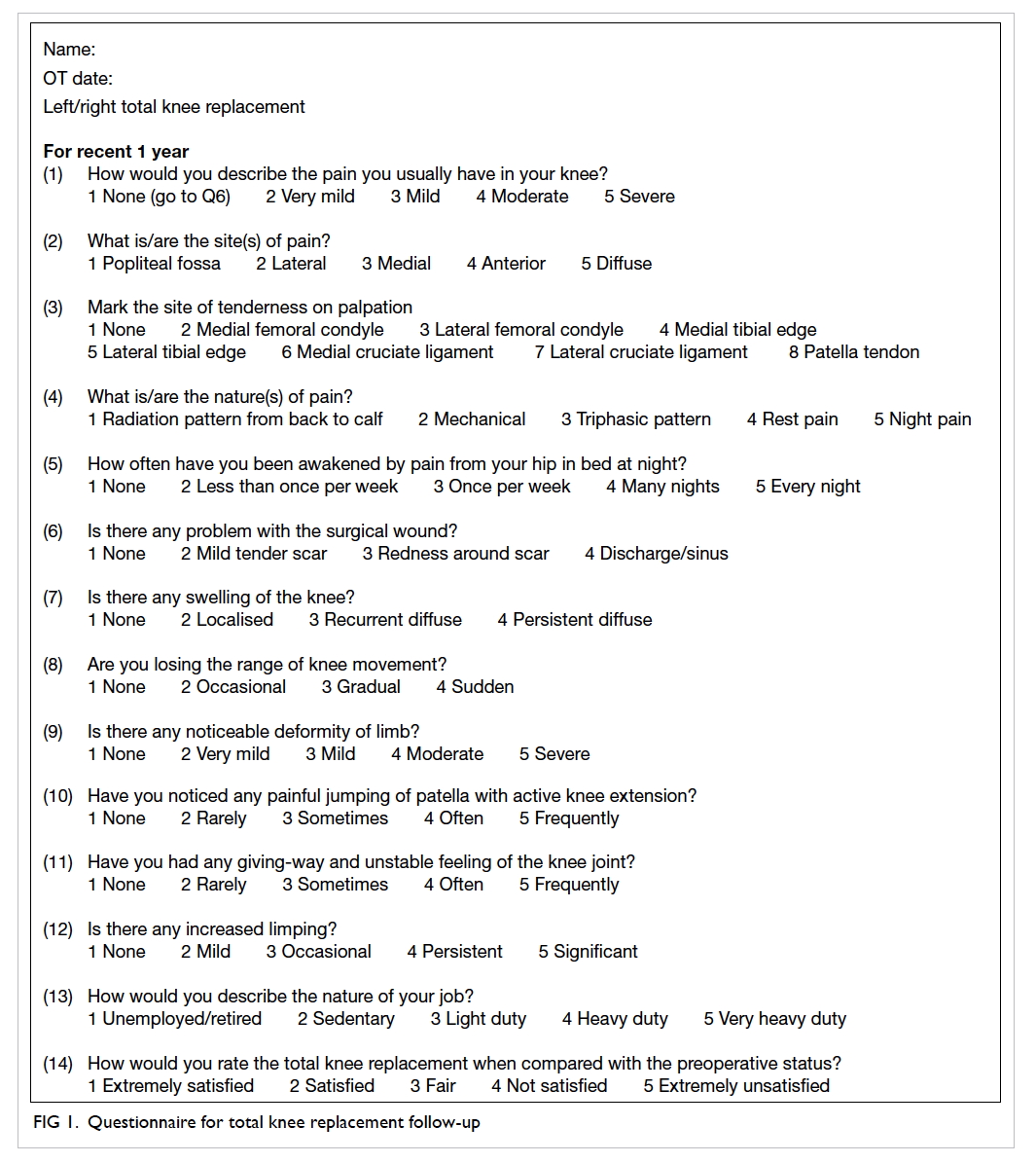

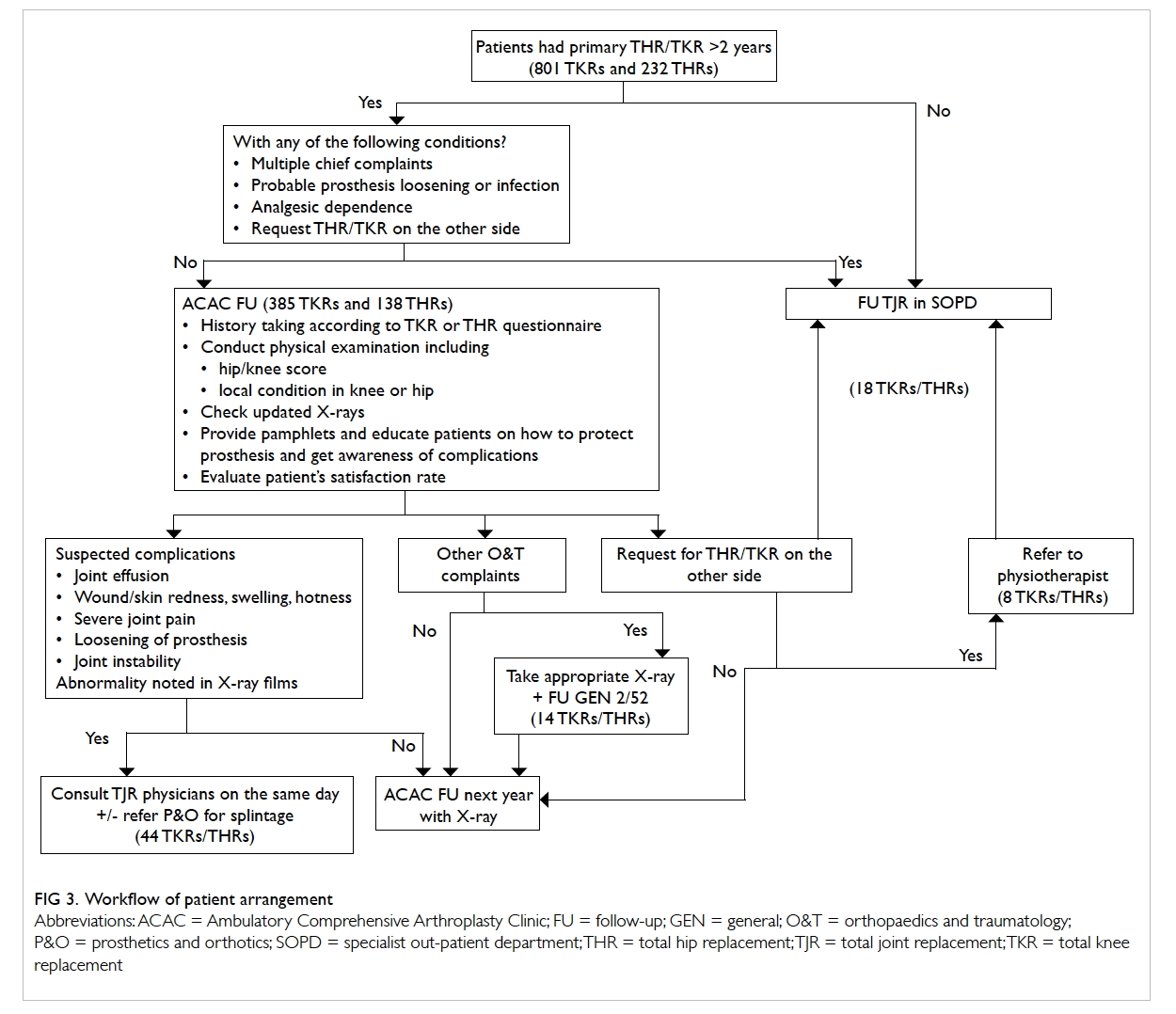

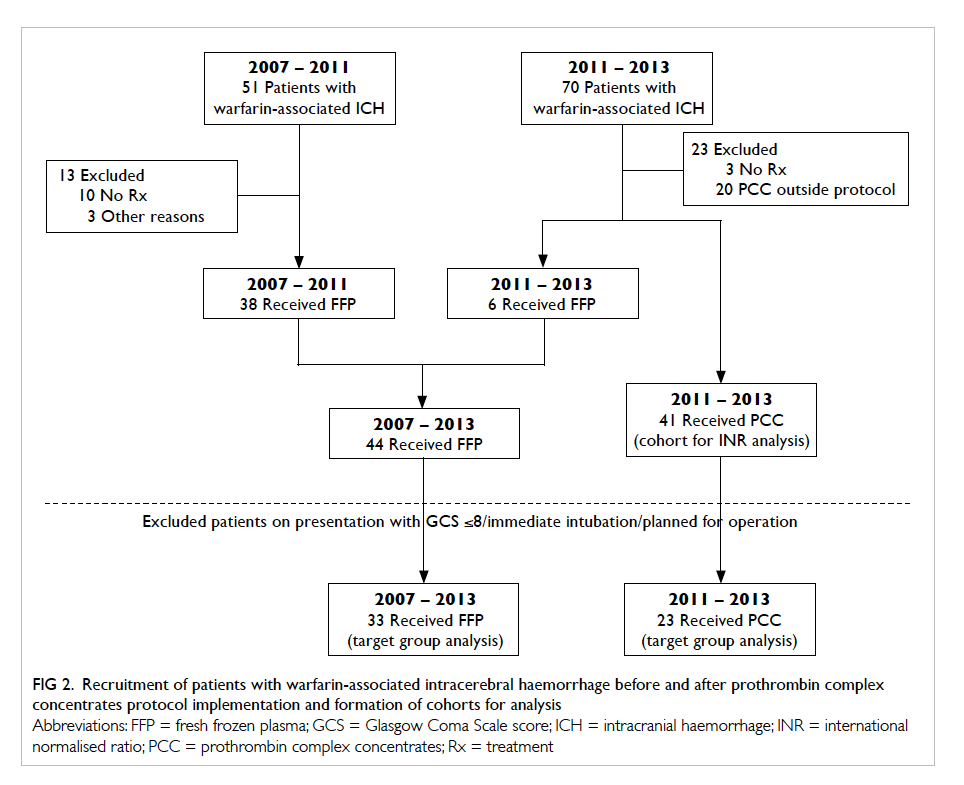

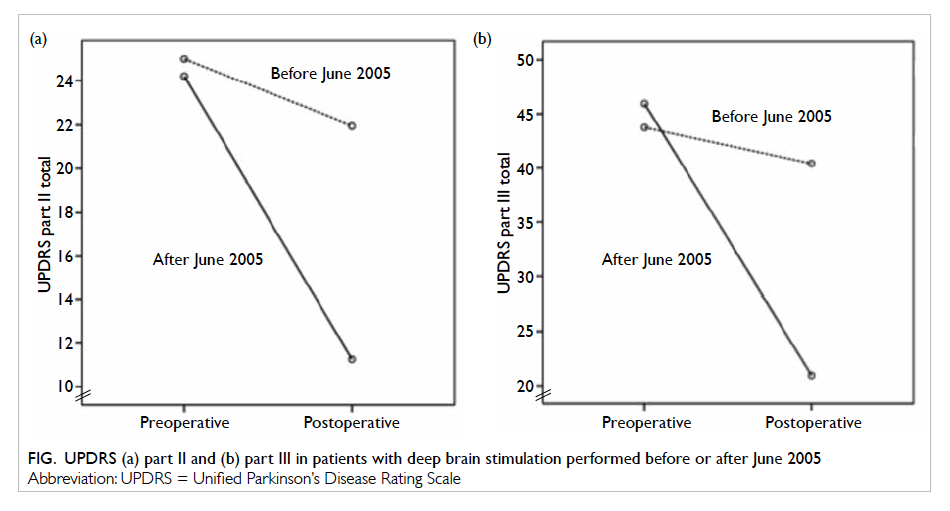

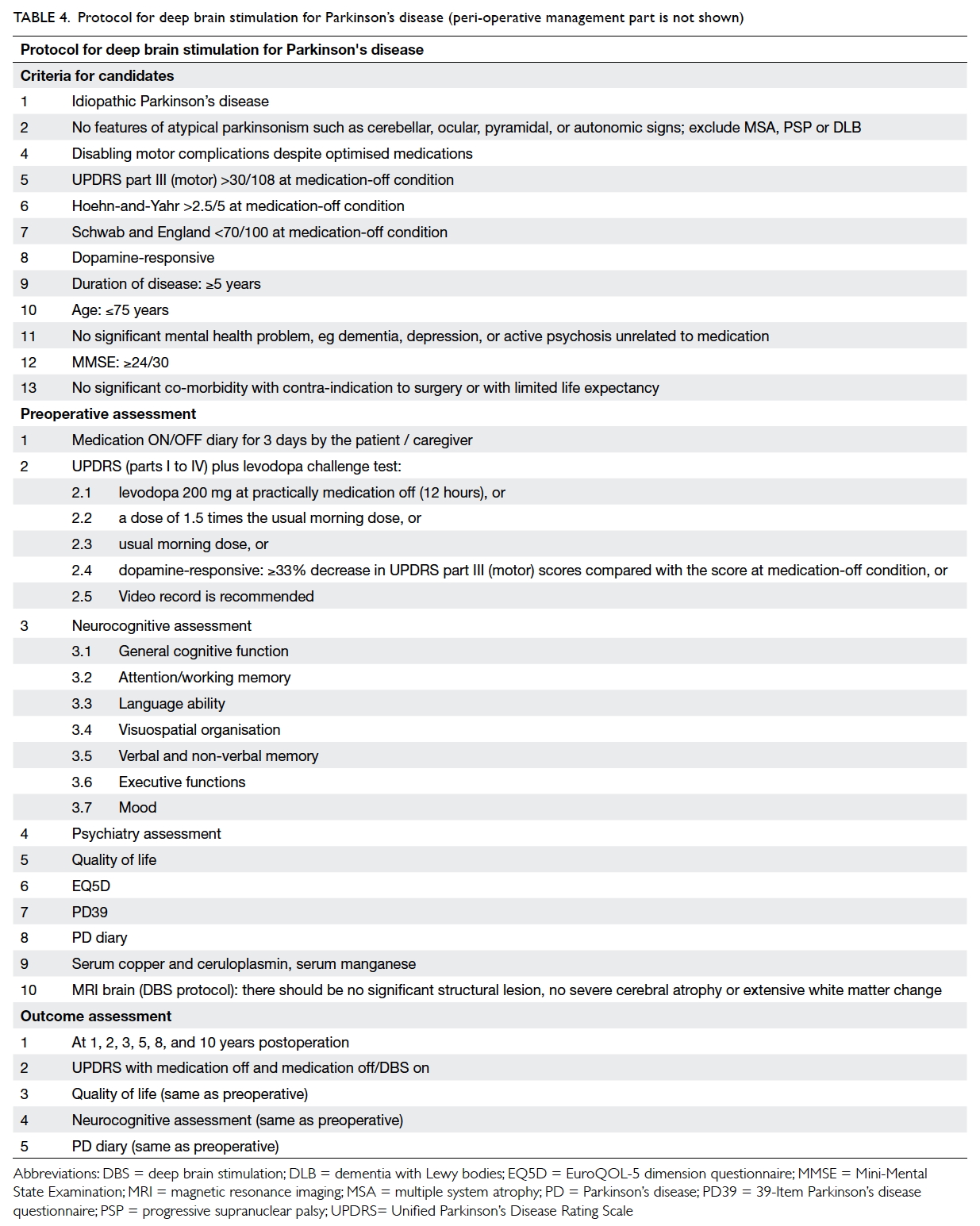

of less than 1 hour (Fig).

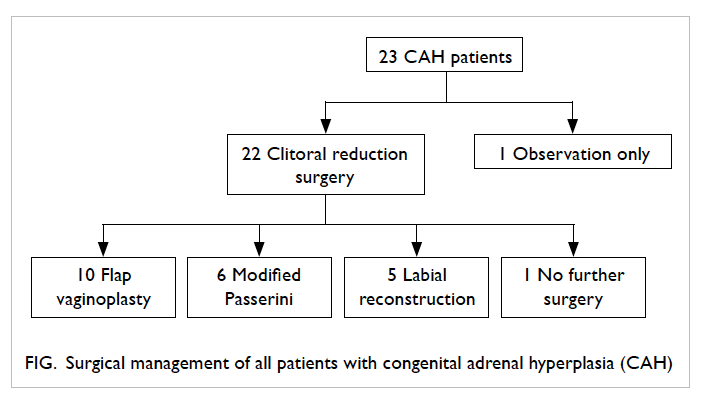

Figure. Protocol for empirical antibiotic treatment in the emergency department for post-chemotherapy febrile haematological malignancy patients

Local publication on post-chemotherapy

patients mainly focused on solid tumour patients,

in-patient management and their outcomes.10

There is a paucity of literature concerning the initial

ED management of haematological malignancy

patients. The objective of this study was to examine

the protocol compliance rate among ED physicians,

the DTA time before and after implementation of the

protocol, and the impact of the protocol on A&E and

hospital services. It also serves to provide invaluable

epidemiological data regarding the haematological

malignancy patients in Hong Kong.

Methods

This is a before-and-after study of the impact of a

protocol on the management of post-chemotherapy

sepsis in haematological malignancy patients. A

2-year retrospective chart review was conducted.

The first chart review was performed from June

2010 to May 2011. These patients were admitted

through ED to the haematological ward prior

to implementation of the protocol and served as

historical referents. Data were retrieved from the

admission book of the haematology ward. A diagnosis

of post-chemotherapy fever or neutropenic fever

was shortlisted. Cases that were admitted through

ED were analysed. The second year started from

June 2011. The intervention group included patients

recruited in the protocol. There were two patients

who fulfilled the inclusion criteria but were excluded

from the study since they refused any investigation

or treatment in ED despite explanation. The charts

were reviewed by two emergency physicians and

two senior nurses. Any discrepancy was resolved by

discussion among investigators. The protocol was

implemented on a 24-hour basis. According to the

protocol, fever was defined by a single measurement

of oral temperature of >38.3°C either at the triage

station or self-reported at home. Neutropenia was

defined as absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of

<1 x 10-9 /L. Sepsis was defined by Bone criteria11

(ie >2 out of 4 of the following: leukocyte count

<4 or >12 x 10-9 /L, respiratory rate >20/min, oral

temperature >38°C or <35°C, pulse >90 beats/min).

Door-to-antibiotic time was charted in the medical

record. Lengths of stay in the A&E and hospital

were retrieved from the Clinical Data Analysis and

Reporting System. The primary outcome was mean

DTA time. Secondary outcomes included compliance

of the ED physician with the protocol, mean ED

length of stay, mean hospital length of stay, and the

adverse outcome rate. Adverse outcomes included

occurrence of a serious medical complication or

death during index admission; these criteria are

commonly cited in oncology literature.12 Adverse

outcome was charted from patients’ medical record

during the index admission.

Chi squared tests were performed when

comparing categorical parameters between the

protocol and referent groups. Student’s t tests were

performed for parametric variables. All statistical

analyses were performed using the Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version

17; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). A P value of less

than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

The study was conducted in the A&E of

QEH, Hong Kong, a tertiary referral centre for

haematological malignancy patients. The A&E of

QEH is an urban ED with a daily attendance of 500

and is one of the busiest EDs in Hong Kong. This

study was approved by the chief of service of the department.

Results

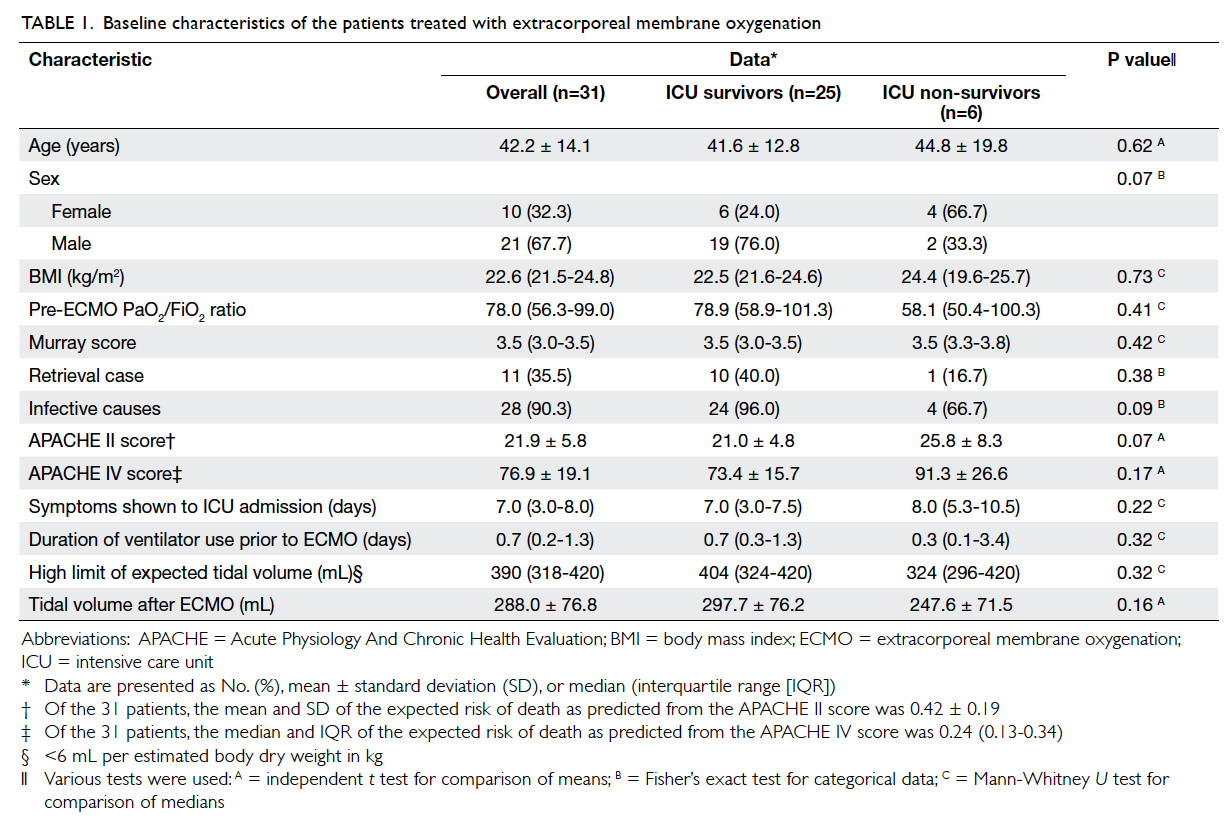

A total of 69 patients were recruited; 19 patients were

referents while 50 belonged to the protocol group.

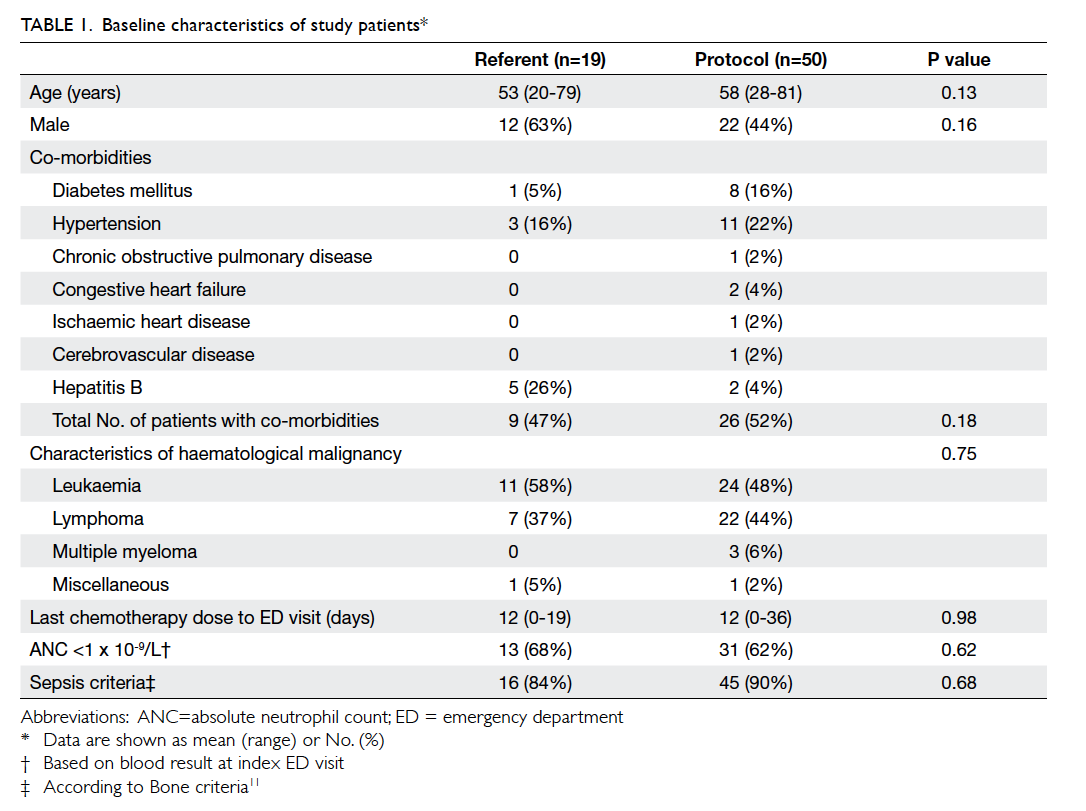

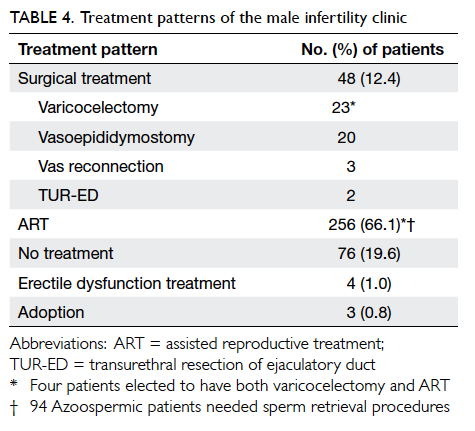

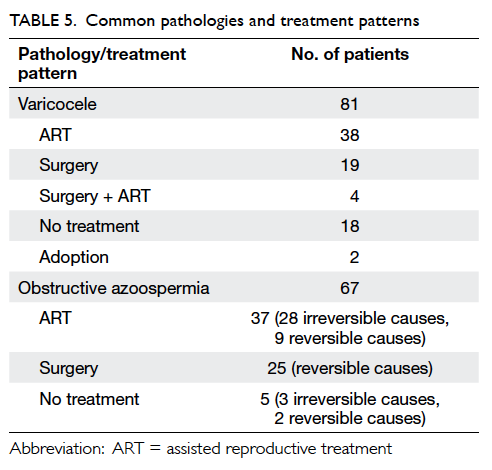

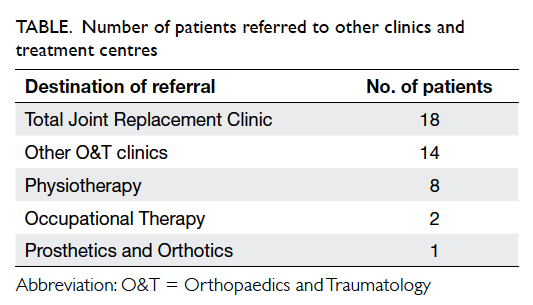

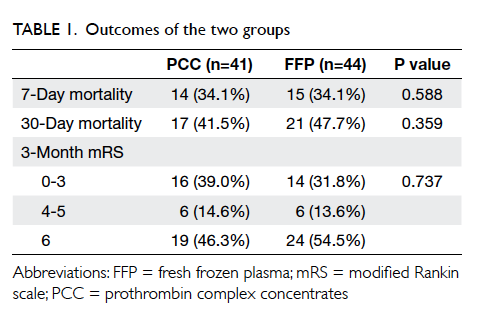

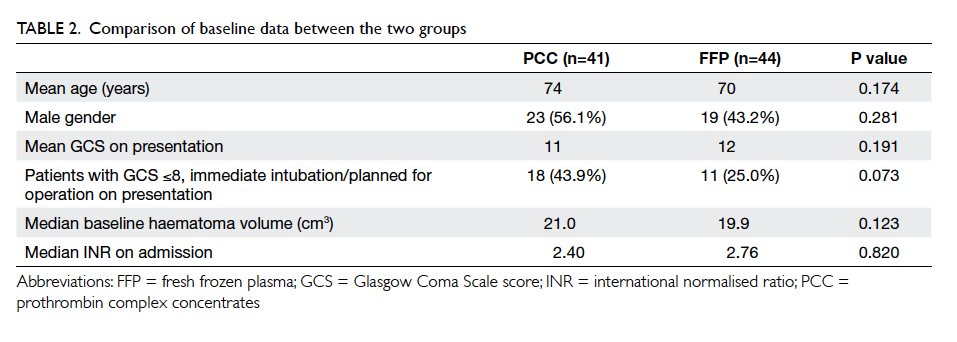

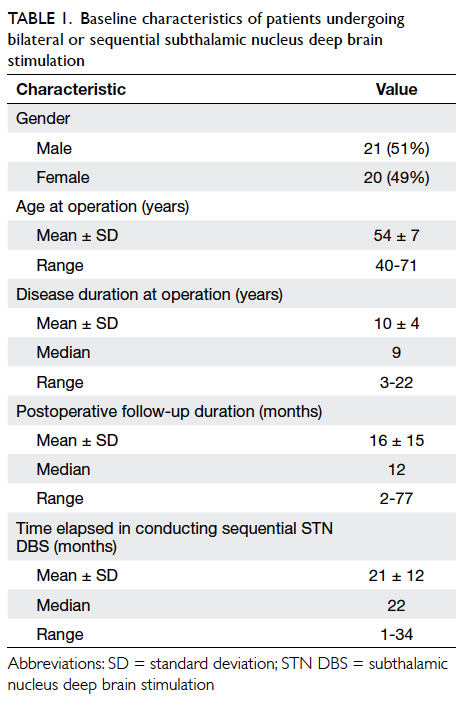

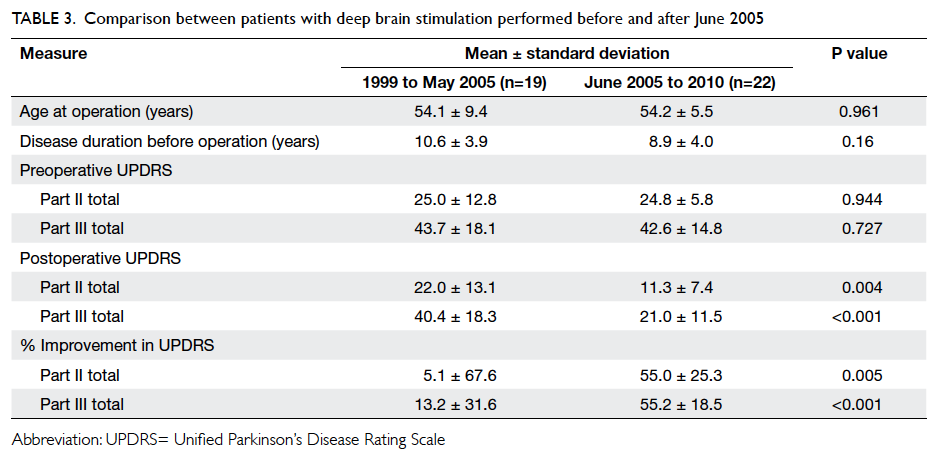

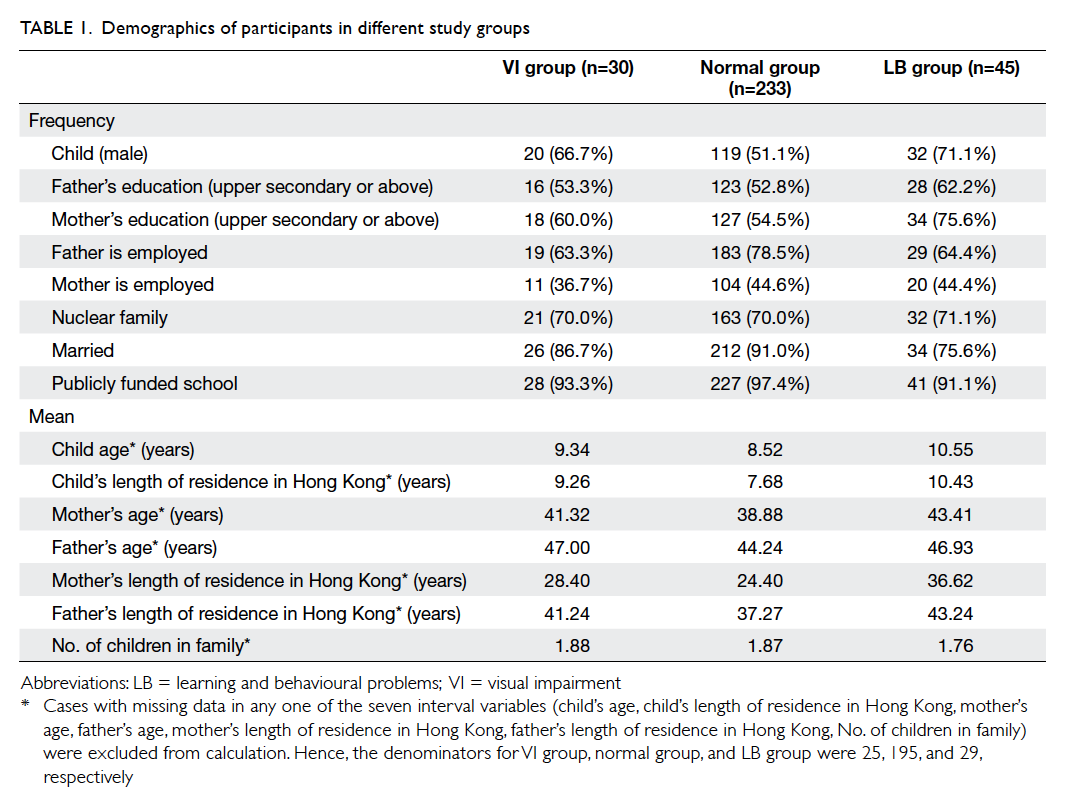

Baseline demographic data are shown in Table 1.

Overall, 49% of the patients were male. Their mean age

was 56 years (range, 20-81 years). Leukaemia was

the most commonly encountered haematological

malignancy, accounting for 51% of cases (n=35/69).

Among these, acute myeloid leukaemia was the most

prevalent subtype. Lymphoma was the second most

common haematological malignancy, making up

42% (n=29/69) of the cases. The mean duration of

the last chemotherapy dose to ED visit was 12 days

in both groups of patients. At least one co-morbidity

was present in 47% of patients in the referent

group and in 52% of patients in the protocol group

(P=0.18).

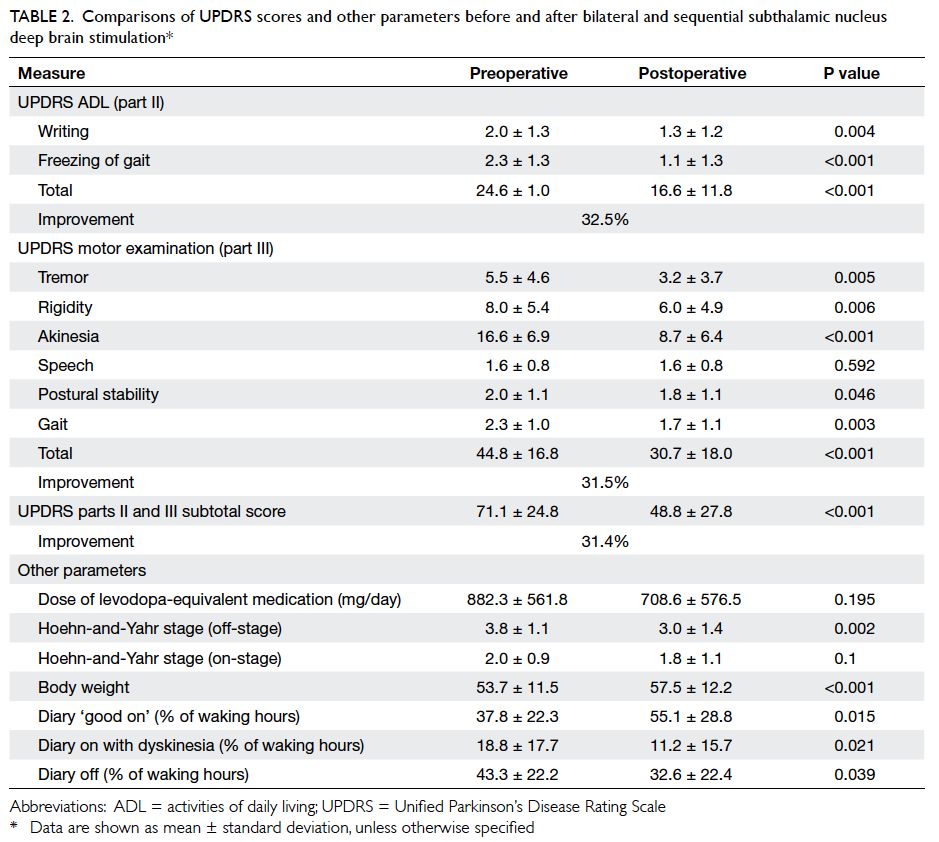

During the index ED visit, the mean door-to-consultation

time was 15 and 12 minutes in referent

group and protocol group, respectively (P=0.40).

Overall, 88% (n=16/19 in referent and n=45/50 in

protocol group) of the patients fulfilled the sepsis

criteria; 64% (n=44/69) had ANC of <1 x 10-9 /L,

although the result was not known at the time of

consultation. All protocol group patients received

antibiotics after blood cultures were taken during

their ED stay compared to none in the control group.

Tazobactam-piperacillin (Tazocin; Pfizer, Taiwan)

was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic in ED.

The mean DTA time in the protocol group was 47

minutes compared to 300 minutes in referent group

(P<0.05). Overall, 86% (n=43/50) of protocol group

patients could achieve the target DTA time of less

than 1 hour (P<0.05). The shortest time required

for antibiotic administration in the referent group was 70 minutes. The mean length of stay in

ED was 105 minutes in the referent group versus 76

minutes in the protocol group (P=0.46). The major

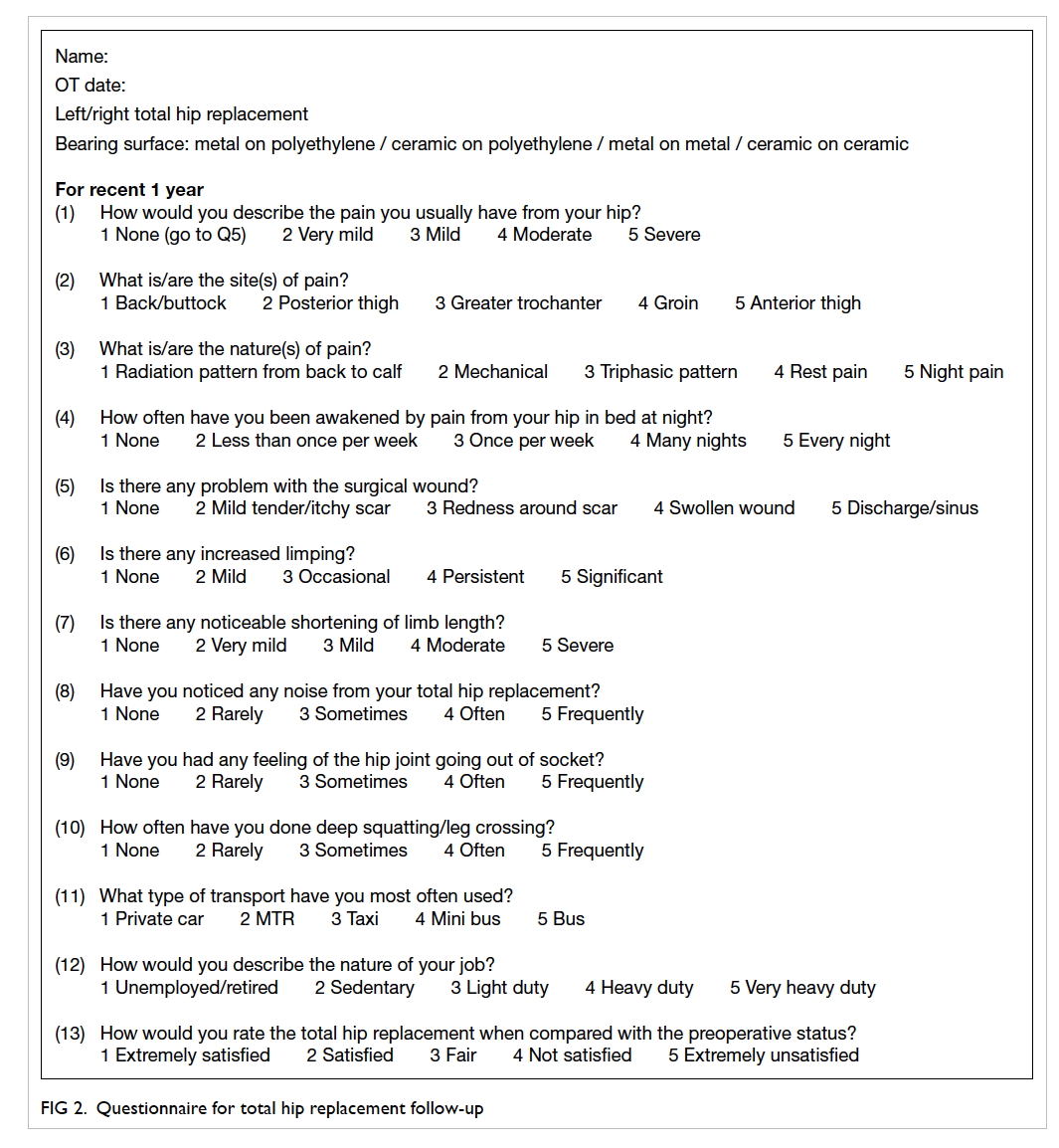

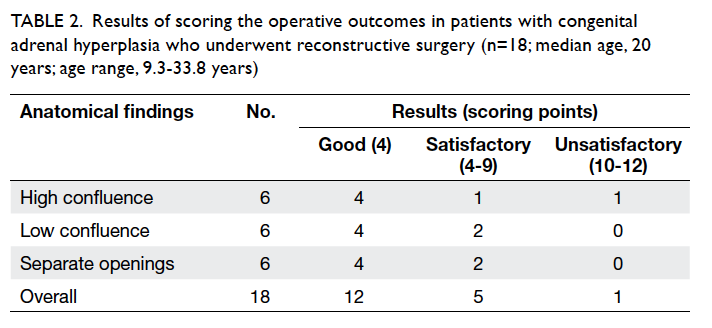

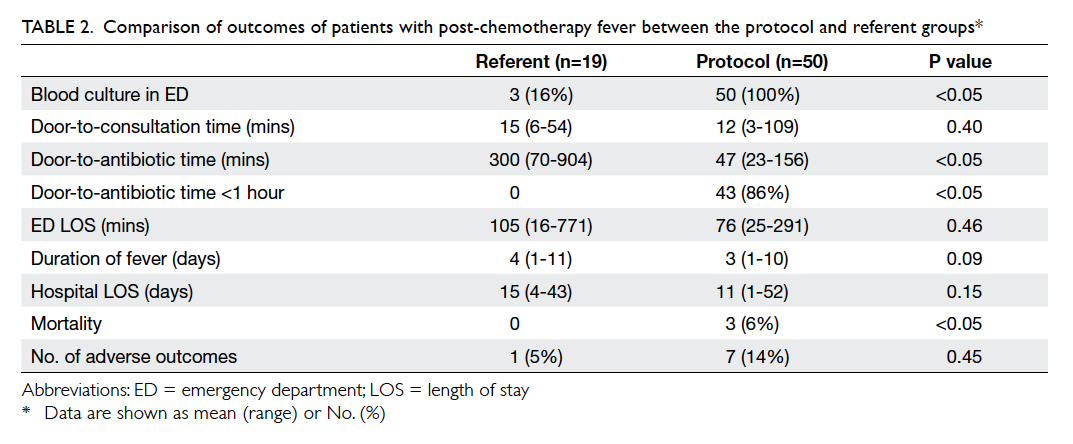

outcomes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of outcomes of patients with post-chemotherapy fever between the protocol and referent groups

The duration of fever, which was defined as

oral temperature of >38°C for 24 hours, was 4 days

in the referent group and 3 days in the protocol

group (P=0.09). One patient from the referent group

suffered from septic shock and required intensive

care unit (ICU) admission; no patient from this

group died. Six patients in the protocol group had

adverse outcomes; three had septic shock requiring

inotropic support, one of them required ICU

admission, while three patients died during index

admission. Adverse event rate was 5% in the referent

group versus 14% in the protocol group (P=0.45).

Overall, 25% (n=17/69) of patients had bacteraemia.

Escherichia coli was recovered in five samples of

which two were extended-spectrum beta-lactamase

(ESBL)–producing bacteria. Streptococcus mitis

was the second most common pathogen and was

found in four samples. Overall, 43% (n=30/69)

of the patients had microbiologically documented

infection. The mean length of hospital stay was 15

days in the referent group compared with 11 days in the

protocol group (P=0.15).

Discussion

Chemotherapy-induced sepsis is a medical

emergency that requires urgent assessment and

treatment with antibiotics. Our study shows that

88% of post-chemotherapy febrile patients fulfilled

the sepsis criteria. Overall, 25% of patients had

bacteraemia, a rate similar to that reported in

the literature.4 Hence, prompt identification and

early administration of broad-spectrum empirical

antibiotics is the cornerstone of management. In

a retrospective study of 2731 patients with septic

shock (only 7% of whom were neutropenic), each

hour delay in initiating effective antimicrobials

decreased survival by around 8%.13 Another cohort

study showed that the in-hospital mortality among

adult patients with severe sepsis or septic shock

decreased from 33% to 20% when time from triage

to appropriate antimicrobial therapy was ≤1 hour

compared with >1 hour.14 Our protocol suggested

Tazocin as the first-line antibiotic, in accordance

with the 2010 Infectious Diseases Society of America

guideline.4 However, the rising trend of ESBL E coli

infection may raise concern of antibiotic resistance.

A larger-scale cohort study should be carried out

to update the local microbiology prevalence and

amend the empirical antibiotic recommendations

accordingly.

Implementation of the protocol in our

department could significantly reduce the mean

DTA time from 300 minutes to 47 minutes (P<0.05).

Furthermore, 86% of patients could achieve the target

DTA time of <1 hour. The result was satisfactory

when compared with similar studies conducted in

Europe and North America where reported median

DTA ranged from 154 minutes to 3.9 hours.15 16 17

Audits from the UK report that only 18% to 26% of

patients receive initial antibiotic within the target

DTA of 1 hour.8 According to the authors, the

most common reasons for failure to comply with

this time frame included failure to administer the

initial dose of the empirical antibacterial regimen

until the patient has been transferred from ED to

the inpatient ward, prolonged time between arrival

and clinical assessment, lack of awareness of the

natural history of neutropenic fever syndrome and

its evolution to severe sepsis and shock, failure of the

ED to stock appropriate antibacterial medications,

and non-availability of neutropenic fever protocols

in the ED for quick reference.8 The last two points

were further supported by studies. A chart review of

201 febrile neutropenic patients in Canada showed

that the electronic clinical practice guideline could

decrease the DTA time by 1 hour (3.9 hours vs 4.9

hours).16 Another retrospective observational study

of timeliness of antibiotic administration in severely

septic patients presenting to a US community ED

showed that storing key antibiotics could decrease

the mean DTA time by 70 minutes (167 minutes

vs 97 minutes).18 The percentage of severely septic

patients receiving antibiotics within 3 hours of arrival

to the ED increased from 65% pre-intervention to

93% post-intervention.18 Before the implementation

of this protocol, multiple briefing sessions were held

with nurses and physicians to increase awareness

about prompt treatment of post-chemotherapy fever.

Antibiotics were stocked in the ED and were readily

available. The protocol could be easily downloaded

from the department website. Regular collaboration

existed between the nursing manager and the

pharmacist to replenish the antibiotic stock. Thus,

successful implementation of the protocol involved

a joint effort by different parties.

There was a trend towards reducing the

duration of fever and length of hospital stay in the

intervention group. Although this does not imply

causation, especially in view of the small sample size,

the correlation makes one ponder whether a delay

in antibiotic delivery indeed increases the length of

hospital stay. Similar correlation was demonstrated

in a UK review.15 However, we could not demonstrate

an impact on mortality and adverse outcome. The

reason may partly be related to the small sample

size, heterogeneous nature of haematological

malignancies, and overall low incidence of mortality

(4%) in our study as compared to 49.8% in-hospital

mortality rate reported in an 11-year review.19 Our

result shows that the length of ED stay was similar

between control and intervention groups, thus,

demonstrating that this protocol did not add further

burden to the overcrowding ED.

This study has two limitations that need to be

discussed. First, the study used a retrospective chart

review design and there were inherent challenges

with missing information and poor documentation.

Second, prior to implementation of the protocol,

the febrile haematological malignant patients were

often instructed to either attend the day ward or

A&E; this partly explains the relatively small case

number in the control group. In addition, we relied

on the diagnosis coding for case identification in the

control group; some cases might have been missed as

a result of error in coding. Even if they attended ED,

the lack of awareness and reluctance of physicians

to prescribe antibiotics led to a significant delay

in administration of the first dose of antibiotic.

Although the number of control cases was small,

mean DTA time of 300 minutes echoed the same in

a similar study performed overseas.16 Efforts were

made to use accepted chart review methods to assess

outcomes that were automatically recorded in the

electronic ED information systems, and to examine

the nurse records of antibiotic administration.

Conclusion

Implementation of a treatment protocol in post-chemotherapy

febrile haematological malignancy

patients can significantly shorten the mean DTA

time to <1 hour, which is now the standard of care

worldwide. The key to effective implementation lies

in orchestration of efforts between administrators,

physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. We can prove

that the protocol is feasible even in a busy urban ED.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Ms Kelly Choy for statistical

analysis.

Declaration

No conflicts of interests were declared by authors.

References

1. Klastersky J. Management of fever in neutropenic patients

with different risks of complications. Clin Infect Dis

2004;39 Suppl 1:S32-7. CrossRef

2. Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH, et al. 2006 Update

of recommendations for the use of white cell growth

factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J

Clin Oncol 2006;24:3187-205. CrossRef

3. Herbst C, Naumann F, Kruse EB, et al. Prophylactic

antibiotics or G-CSF for the prevention of infections

and improvement of survival in cancer patients

undergoing chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2009;(1):CD007107.

4. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice

guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic

patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases

Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:e56-93. CrossRef

5. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis

campaign: international guidelines for management

of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med

2013;41:580-637. CrossRef

6. Bate J, Gibson F, Johnson E, et al. Neutropenic sepsis:

prevention and management of neutropenic sepsis in

cancer patients (NICE Clinical Guideline CG151). Arch

Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2013;98:73-5. CrossRef

7. Flowers CR, Seidenfeld J, Bow EJ, et al. Antimicrobial

prophylaxis and outpatient management of fever and

neutropenia in adults treated for malignancy: American

Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J

Clin Oncol 2013;31:794-810. CrossRef

8. Clarke RT, Warnick J, Stretton K, Littlewood TJ. Improving

the immediate management of neutropenic sepsis in

the UK: lessons from a national audit. Br J Haematol

2011;153:773-9. CrossRef

9. André S, Taboulet P, Elie C, et al. Febrile neutropenia in

French emergency departments: results of a prospective

multicentre survey. Crit Care 2010;14:R68. CrossRef

10. Hui EP, Leung LK, Poon TC, et al. Prediction of outcome

in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia: a prospective

validation of the Multinational Association for Supportive

Care in Cancer risk index in a Chinese population and

comparison with the Talcott model and artificial neural

network. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1625-35. CrossRef

11. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis

and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative

therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus

Conference Committee. American College of Chest

Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest

1992;101:1644-55. CrossRef

12. Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, et al. The

Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer

Risk Index: a multinational scoring system for identifying

low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol

2000;18:3038-51.

13. Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of

hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial

therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human

septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1589-96. CrossRef

14. Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, et al. Impact of time

to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis

or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was

initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med

2010;38:1045-53. CrossRef

15. Sammut SJ, Mazhar D. Management of febrile neutropenia

in an acute oncology service. QJM 2012;105:327-36. CrossRef

16. Lim C, Bawden J, Wing A, et al. Febrile neutropenia in EDs:

the role of an electronic clinical practice guideline. Am J

Emerg Med 2012;30:5-11, 11.e1-5.

17. Nirenberg A, Mulhearn L, Lin S, Larson E. Emergency

department waiting times for patients with cancer with

febrile neutropenia: a pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum

2004;31:711-5. CrossRef

18. Hitti EA, Lewin JJ 3rd, Lopez J, et al. Improving door-to-antibiotic

time in severely septic emergency department

patients. J Emerg Med 2012;42:462-9. CrossRef

19. Legrand M, Max A, Peigne V, et al. Survival in neutropenic

patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Crit Care Med

2012;40:43-9. CrossRef

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: