Multicentre study of hospitalised patients with sports- and recreational cycling–related traumatic brain injury in Hong Kong

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Multicentre study of hospitalised patients

with sports- and recreational cycling–related traumatic brain injury in Hong Kong

Peter YM Woo, MMedSc, FRCS1; Eric Cheung, MRCS1; Fion WY Lau, MB, ChB1; Nancy WS Law, MB, ChB1; Carly KY Mak, MB, ChB1; Peony Tan, BMed MD1; Bertrand Siu, MB, BS1; Anson Wong, MB, ChB1; Calvin HK Mak, MB, BS, FRCS2; KY Chan, FRCS1; KY Yam, FRCS3; KY Pang, FRCS4; YC Po, FRCS5; WM Lui, FRCS6; Danny TM Chan, FRCS7; WS Poon, FRCS, PhD7

1 Department of Neurosurgery, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Neurosurgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Neurosurgery, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Department of Neurosurgery, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

5 Department of Neurosurgery, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

6 Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

7 Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Peter YM Woo (wym307@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Cycling is associated with a greater

risk of traumatic brain injury (TBI) than other

recreational activities. This study aimed to investigate

the epidemiology of sports-related TBI in Hong

Kong and to examine predictors for recreational

cycling-induced intracranial haemorrhage.

Methods: This retrospective multicentre study

included patients diagnosed with sports-related TBI

in public hospitals in Hong Kong from 2015 to 2019.

Computed tomography scans were reviewed by an

independent assessor. The primary endpoint was

traumatic intracranial haemorrhage. The secondary

endpoint was an unfavourable Glasgow Outcome

Scale (GOS) score at discharge from hospital.

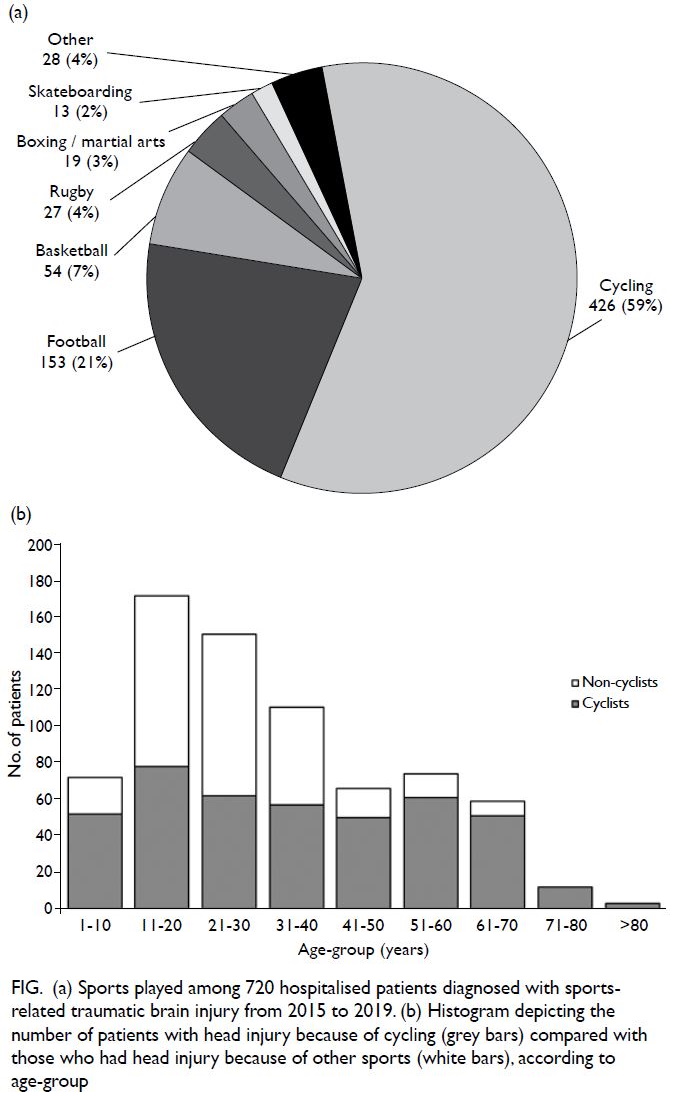

Results: In total, 720 patients were hospitalised with

sports-related TBI. The most common sport was

cycling (59.2%). The crude incidence of cycling-related

TBI was 1.1 per 100 000 population. Cyclists were

more likely to exhibit intracranial haemorrhage and

an unfavourable GOS score, compared with patients

who had TBI because of other sports. Although 47%

of cyclists had intracranial haemorrhage, only 15%

wore a helmet. In multivariate analysis, significant

predictors for intracranial haemorrhage were age

≥60 years, antiplatelet medication, moderate or

severe TBI, and skull fracture. Among 426 cyclists,

375 (88%) had mild TBI, and helmet wearing

was protective against intracranial haemorrhage,

regardless of age, antiplatelet medication intake, and

mechanism of injury. Of 426 cyclists, 31 (7.3%) had

unfavourable outcomes on discharge from hospital.

Conclusions: The incidence of sports-related TBI

is low in Hong Kong. Although cycling-related head injuries carried greater risks of intracranial

haemorrhage and unfavourable outcomes compared

with other sports, most cyclists experienced good

recovery. Helmet wearing among recreational

cyclists with mild TBI was protective against

intracranial haemorrhage and skull fracture.

New knowledge added by this study

- The incidence of sports-related traumatic brain injury (TBI) is lower in Hong Kong than in other countries or regions; cycling is the sport most frequently associated with TBI.

- A greater proportion of hospitalised patients with cycling-related TBI had intracranial haemorrhage and unfavourable functional outcomes, compared with patients who had TBI because of other sports. Risk factors for intracranial haemorrhage were older age (>60 years), antiplatelet medication intake, moderate or severe TBI, and skull fracture.

- Only 15% of hospitalised patients with cycling-related TBI wore a helmet at the time of injury; none of the patients who died had been wearing a helmet.

- The lack of an independent association with motor vehicle collisions suggests that recreational cycling at comparatively low speeds without protective head gear can be fatal.

- Cycling is becoming increasingly popular, but Hong Kong is one of the most dangerous regions in the world for cyclists in terms of fatality rate.

- Public health policies that improve bicycle rider safety (eg, mandatory helmet legislation) should be deliberated. Although helmet wearing is protective against intracranial haemorrhage for mild TBI individuals, the rate of its adoption is low.

- Measures to control the risk of sports-related TBI should be carefully considered when designing public health policies to promote sports engagement.

Introduction

Considerable physical and psychosocial benefits are

associated with participation in sporting activities.1 2

Physical activity has been demonstrated to reduce

the risks of coronary heart disease, some cancers,

obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.2 3 4 5 6

Its obvious merits have prompted several national

health programmes, including the health programme

in Hong Kong, to promote sports to the general

public.7 8 9 However, sports participation carries a risk

of injury, especially traumatic brain injury (TBI). It

has been estimated that 20% of all TBIs are sports-related.10 In addition, up to 20% of sports-related

TBI survivors (usually adolescents or young adults)

experience chronic symptoms including headache,

fatigue, and cognitive and balance difficulties.11 There

is a global trend of increasing sports-related TBI

incidence: from 3.5 to 31.5 per 100 000 population

in the past decade.12 13 Because many patients with

mild TBI do not seek medical attention, these

figures likely underestimate the total burden of this

condition.13 Population-based studies reviewing

sports-related TBI are sparse; most target specific

groups of individuals (eg, professional athletes) or

rely on self-reporting surveys that lack a uniform

definition and comprehensive assessment of brain

injury.14 For similar reasons, studies reviewing

outcome predictors have also been inadequate, thus

hindering the generation of meaningful conclusions

to guide governmental policy initiatives.14

Hong Kong is highly urbanised with an

established public transport system, such that cycling

is mainly regarded as a recreational activity.15 16 In

terms of fatality rate, Hong Kong is among the most

dangerous areas for cycling, compared with other

cities such as New York, the US, or countries such as

France.17

This study was performed to document the

epidemiology of sports-related TBI among patients

who required inpatient care by adopting territory-wide

uniform diagnostic coding criteria, clear data

definitions, and systematic assessments of radiologic

findings. Because cycling is a popular sport in Hong

Kong, factors predictive of intracranial haemorrhage

(eg, the effect of helmet use) and poor functional

outcomes among cyclists hospitalised with TBI were

determined.

Methods

Patients who required inpatient care at any Hospital

Authority institution for sports-related TBI

from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2019 were

reviewed. The Hospital Authority is a public health

service highly subsidised by the Hong Kong SAR

Government; it is responsible for 90% of inpatient

bed days in the city. Patients were identified by

the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification code (ICD-10-CM)

designation for TBI 854.0 secondary to a sports-related

external cause (E codes: E006-10). Data

from clinical records, operation notes, medication

prescriptions, and computed tomography (CT)

brain scans from a central digital imaging repository

were reviewed. In particular, the type of sport played,

the clinical presentation of symptoms, the Injury

Severity Score (ISS), the need for neurosurgery,

length of hospitalisation, and diagnosis of post-concussion

syndrome were recorded. Head injury

was classified into mild (presenting Glasgow Coma

Scale [GCS] score, 14-15); moderate (presenting

GCS score, 9-13), and severe (presenting GCS

score, 3-8), in accordance with criteria established

by the Neurotraumatology Committee of the World

Federation of Neurosurgical Societies.18 Post-concussion

syndrome was defined in accordance

with ICD-10 criteria. This required a 4-week duration

of symptoms from at least three categories following

a traumatic loss of consciousness. The symptom

categories were headache, irritability, concentration

impairment, insomnia, and a preoccupation with

the aforementioned symptoms. For neurosurgical

patients with cycling related–TBI, the mechanism

of injury and their experience level (ie, professional

athlete or amateur rider) were documented. All CT scans were reviewed by an independent assessor with

6 months of neurosurgical training experience who

was blinded to the patients’ clinical characteristics

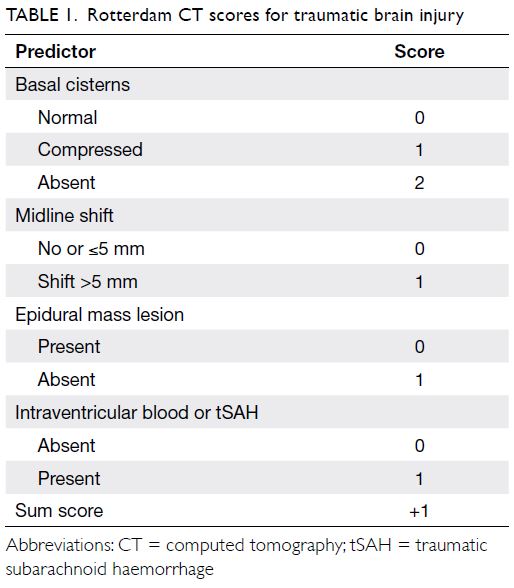

and outcomes. The scans were first evaluated using the

Rotterdam CT score, a commonly utilised validated

radiological assessment system for the prognosis of

patients with TBI. The classification has four distinct

elements that require the appraisal of the degree of

basal cistern obliteration, degree of midline shift,

the presence (or absence) of an epidural mass lesion,

and the presence (or absence) of intraventricular or

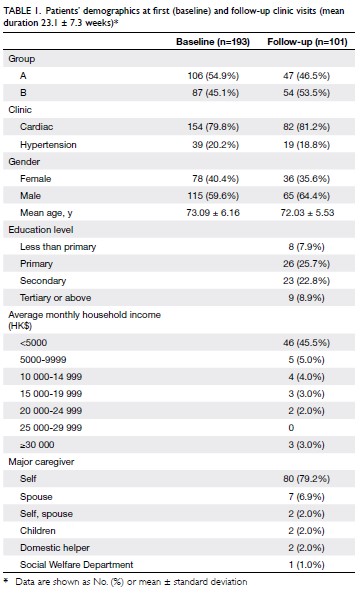

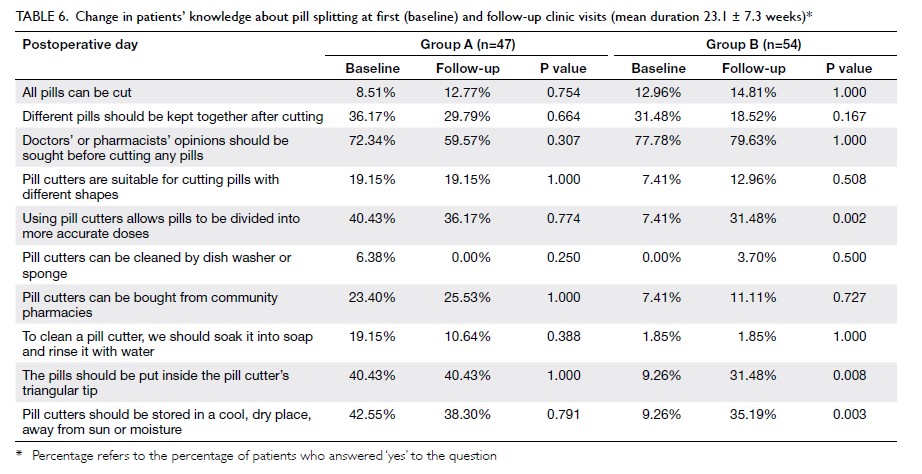

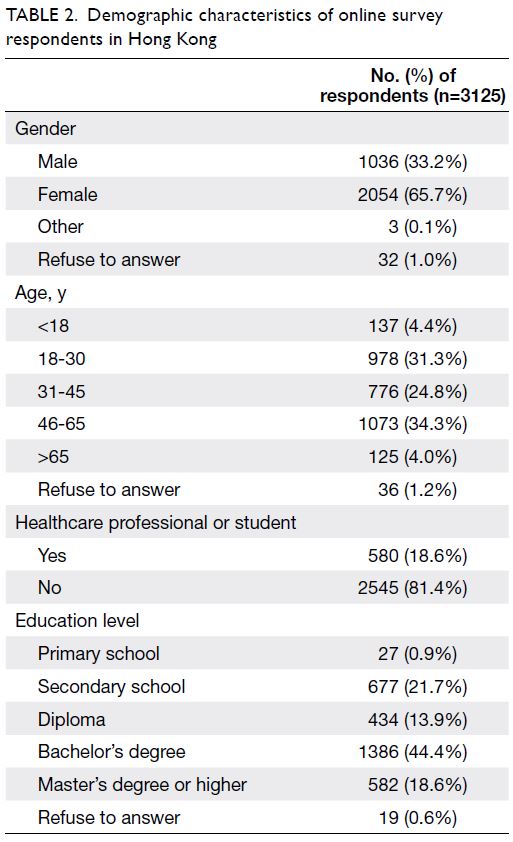

traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage (Table 1). In

addition, the scans were assessed for skull fractures,

cerebral contusions, and acute subdural haematomas

(ASDHs). The primary outcome of the study was

the presence of intracranial haemorrhage on the

admitting CT scan. All potential predictors were

categorised into patient-related, trauma-related, and

radiological factors. The secondary outcome was

unfavourable functional performance, defined as a

Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 3 to 5 on

discharge from the hospital (3, severe disability; 4,

persistent vegetative state; and 5, death).

Statistical analyses utilised the Chi squared

test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical

data such as patient gender or the use of antiplatelet

medication. Independent-samples t test was used

for continuous data such as patient age or duration

of hospitalisation. Multivariate binary logistic

regression was used to identify independent factors

for the presence (or absence) of traumatic intracranial

haemorrhage. A P value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant. Statistical analysis was

conducted using SPSS (Windows version 20.0; IBM

Corp, Armonk [NY], US).

Results

Overall characteristics of patients with

sports-related traumatic brain injury during the study period

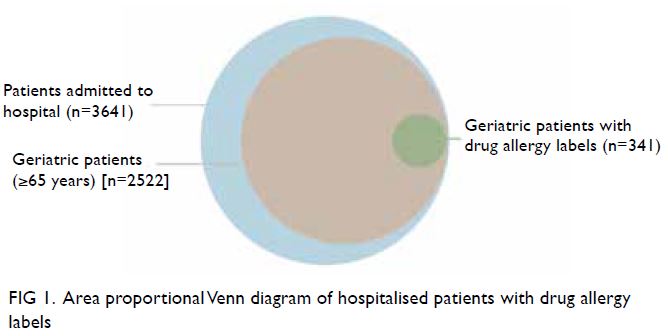

In total, 720 consecutive patients were hospitalised

with sports-related TBI during the 5-year study

period, and 705 (97.9%) of them were admitted

under neurosurgical care. This was equivalent

to a crude incidence of 1.9 per 100 000 general

population. The mean (± standard deviation [SD])

age was 32 ± 19 years; 521 (72.4%) patients were

adults (≥18 years) and 568 (78.9%) were male. The

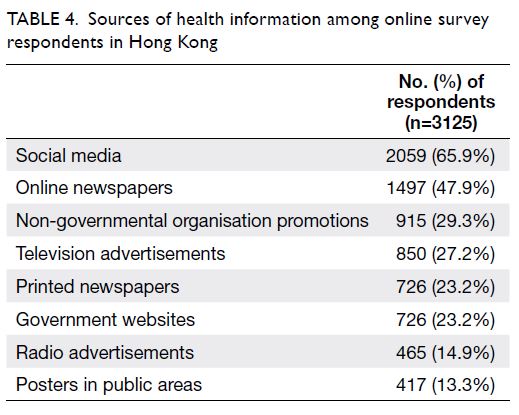

most common sport was cycling (59.2%), followed

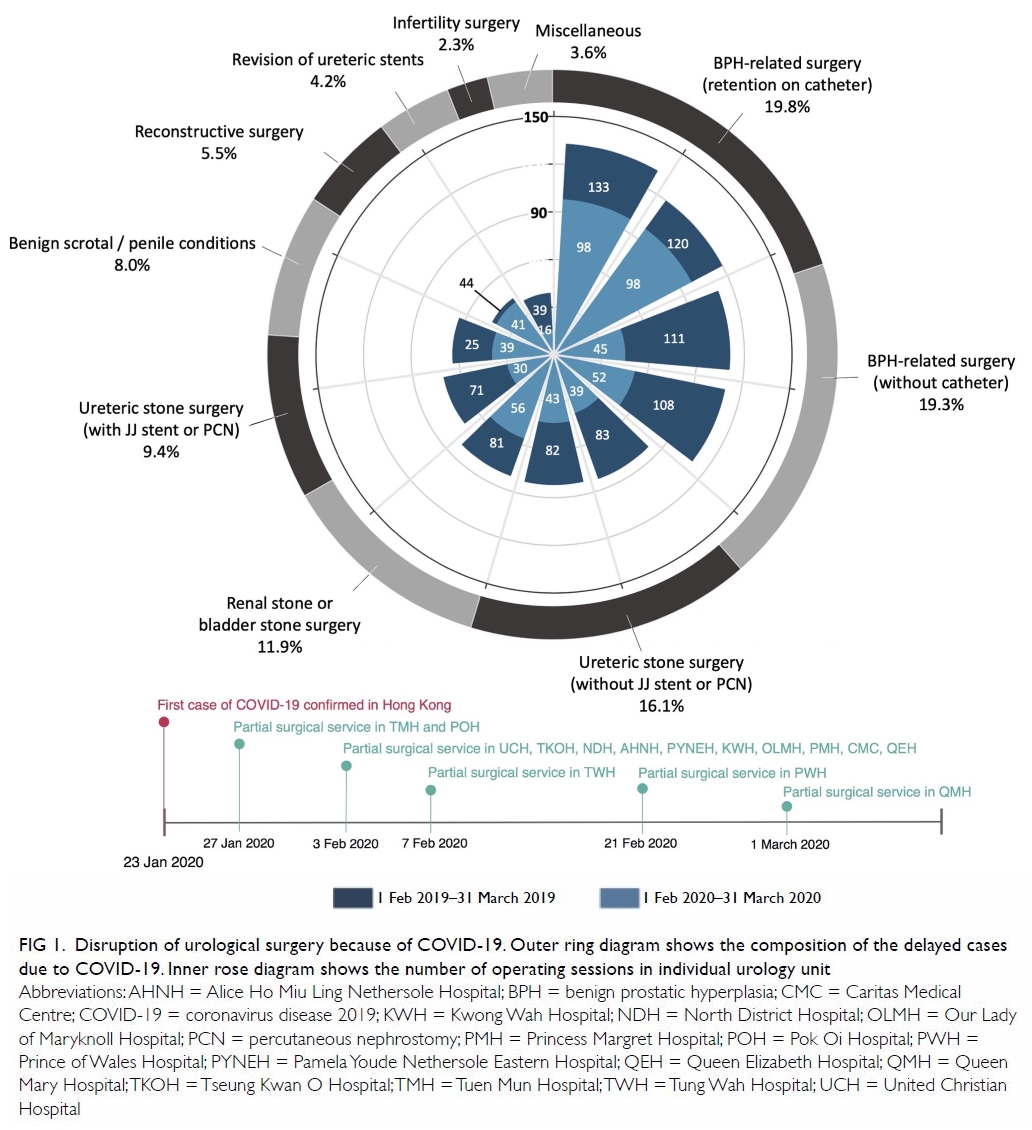

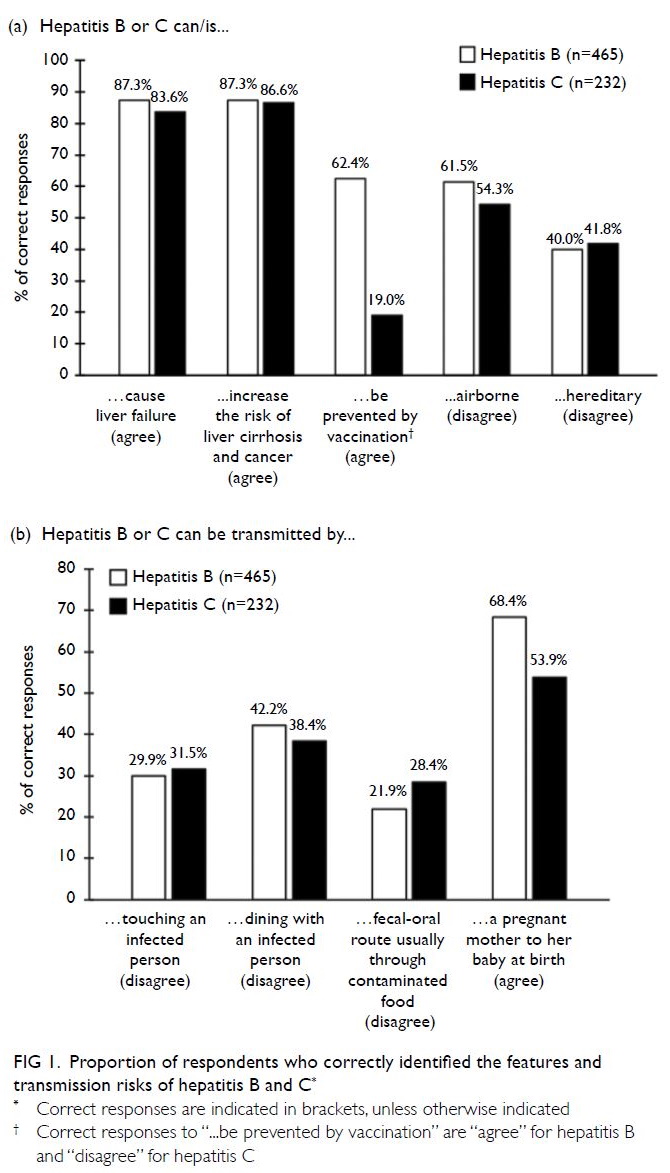

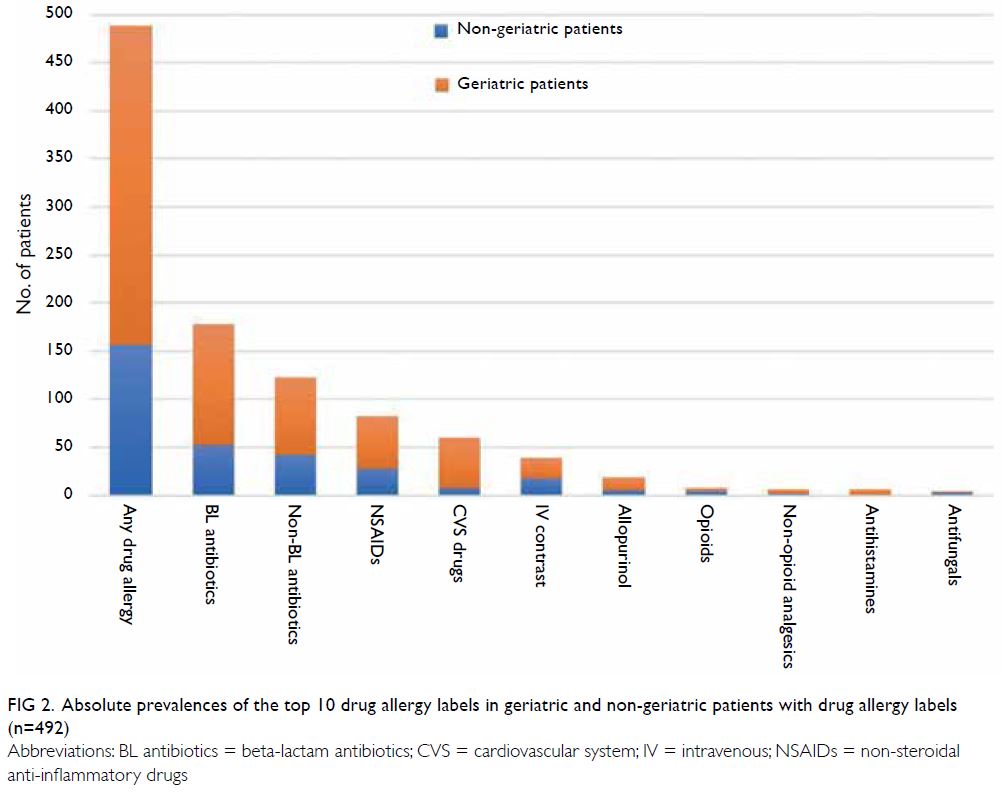

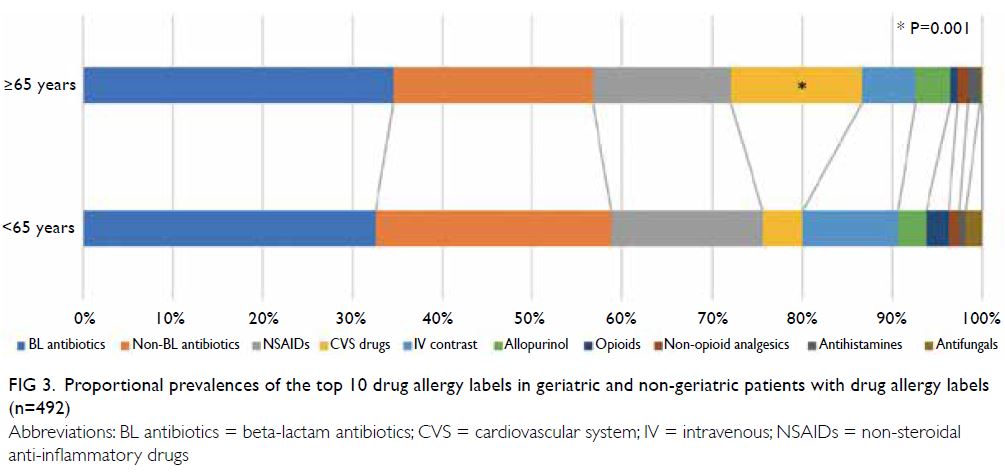

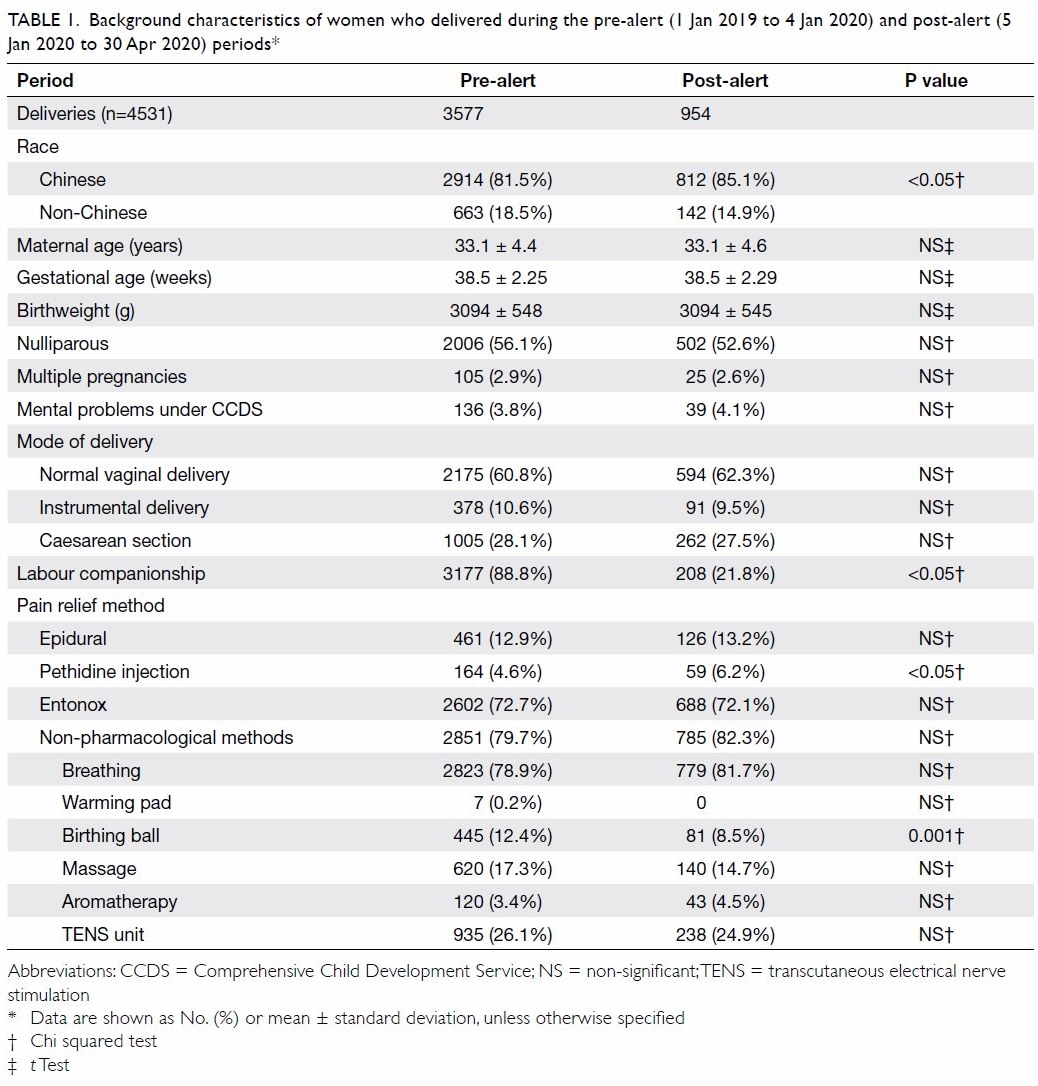

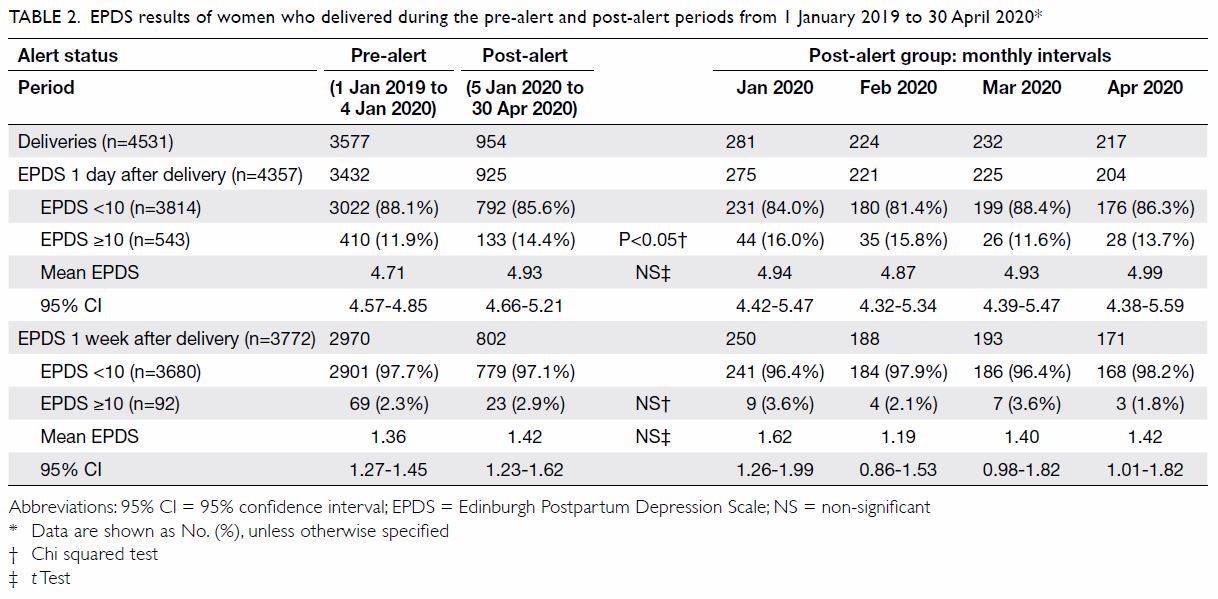

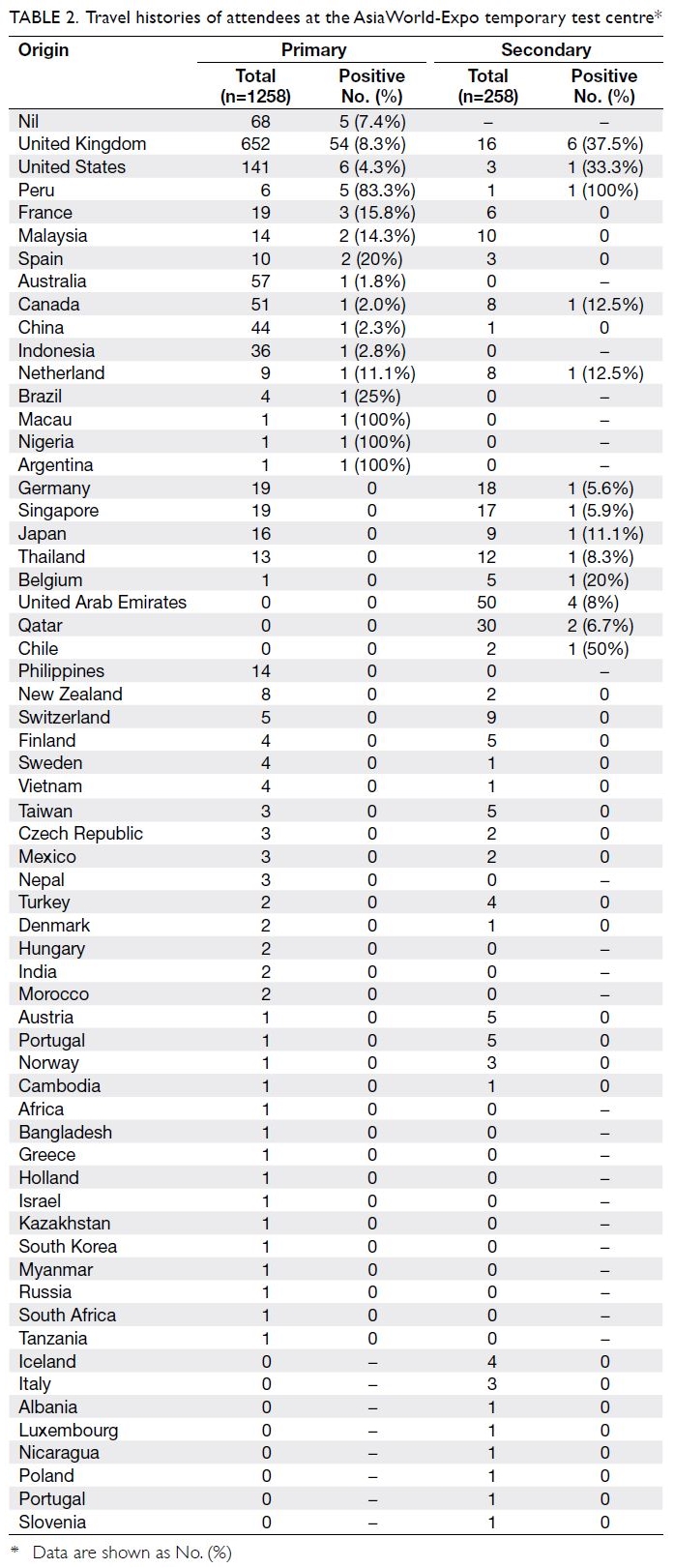

by football (21.3%) and basketball (7.5%) [Fig a].

On admission, most (86.1%) patients were fully

conscious. Overall, 658 (91.4%) patients had mild

TBI, 41 (5.7%) patients had moderate TBI, and

21 (2.9%) patients had severe TBI. Post-traumatic

seizures occurred in 36 (5.0%) patients. Furthermore,

324 (45.0%) patients had a loss of consciousness and

269 (37.4%) patients experienced post-traumatic

retrograde amnesia. Only 19 (2.6%) patients

were taking either antiplatelet or anticoagulant

medication. Extracranial injuries were sustained

by 208 (28.9%) patients; among them, injuries were

mainly either limb abrasions or contusions (62.1%).

The median ISS was 2 (interquartile range=2-8).

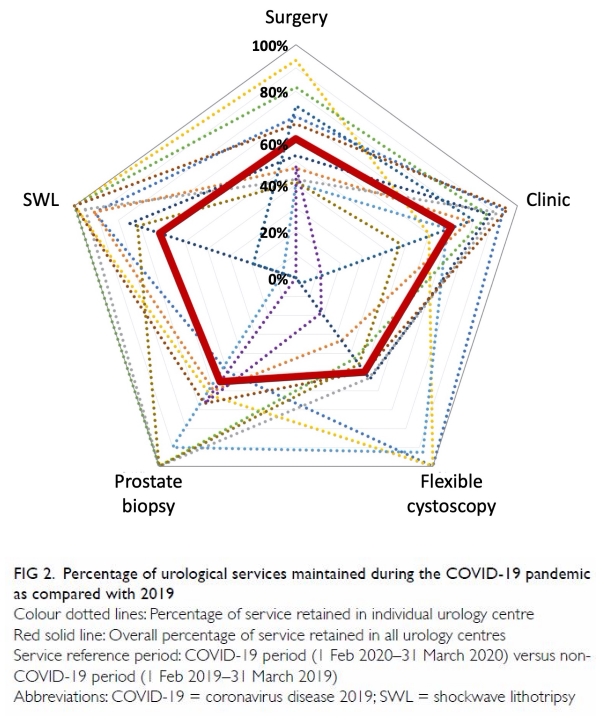

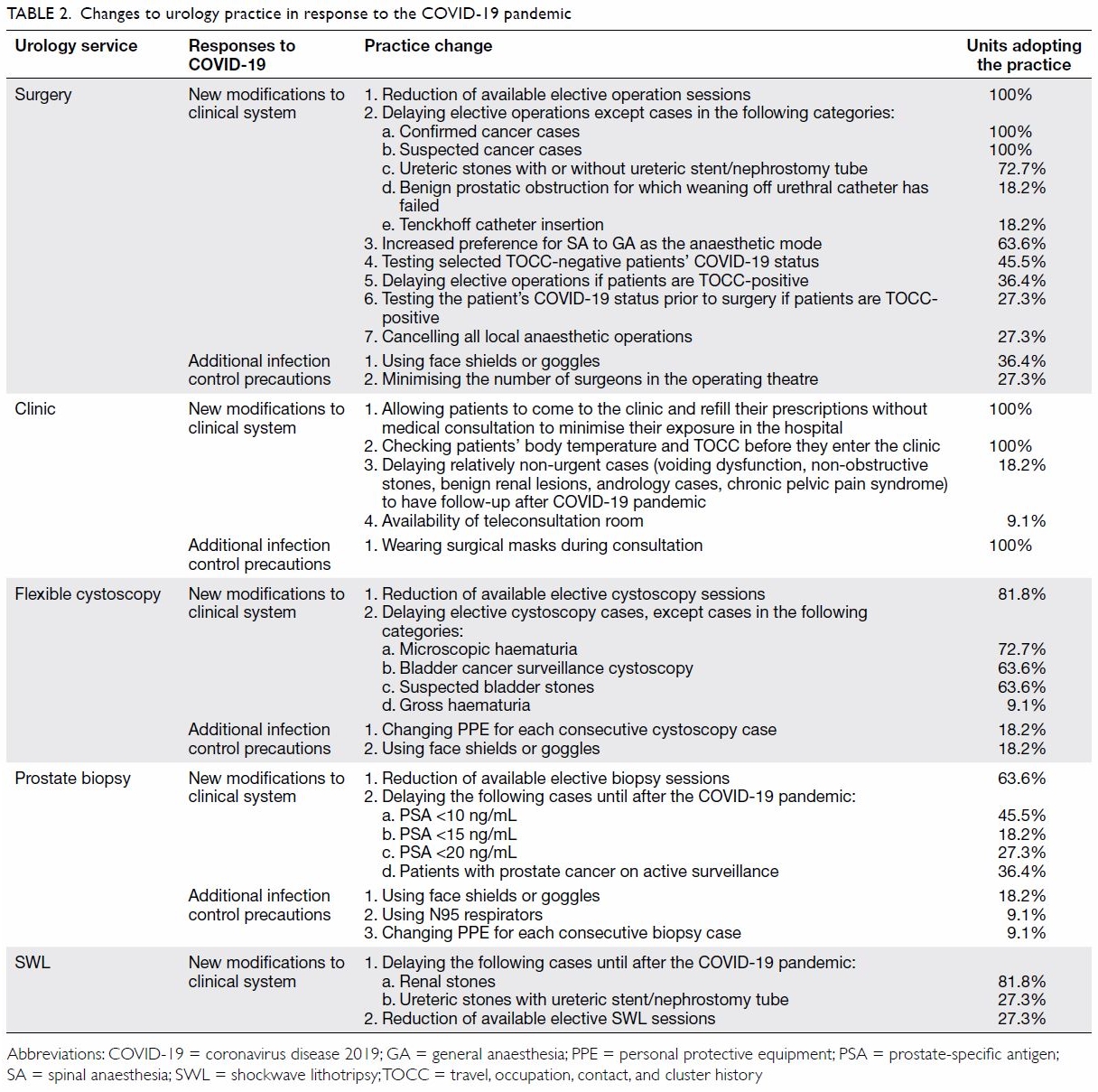

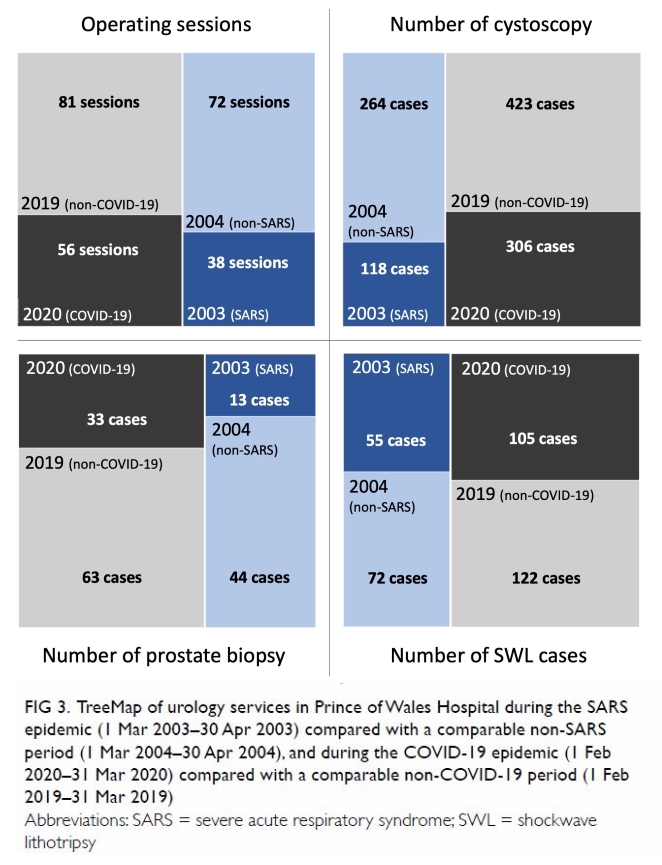

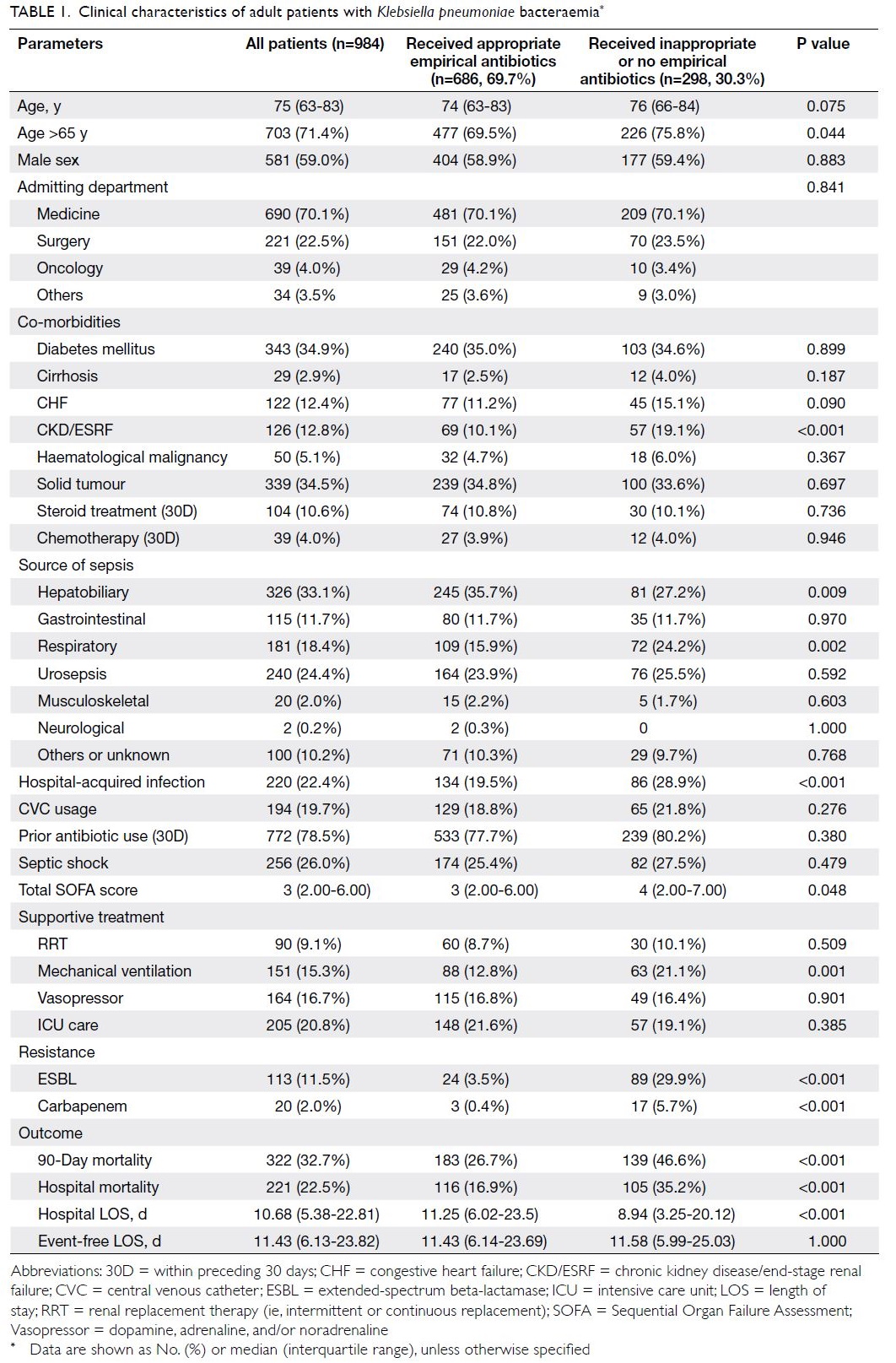

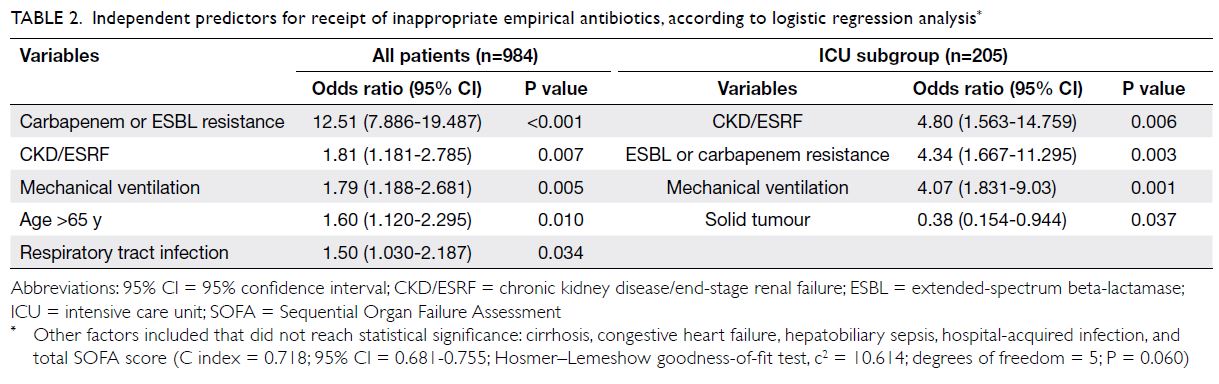

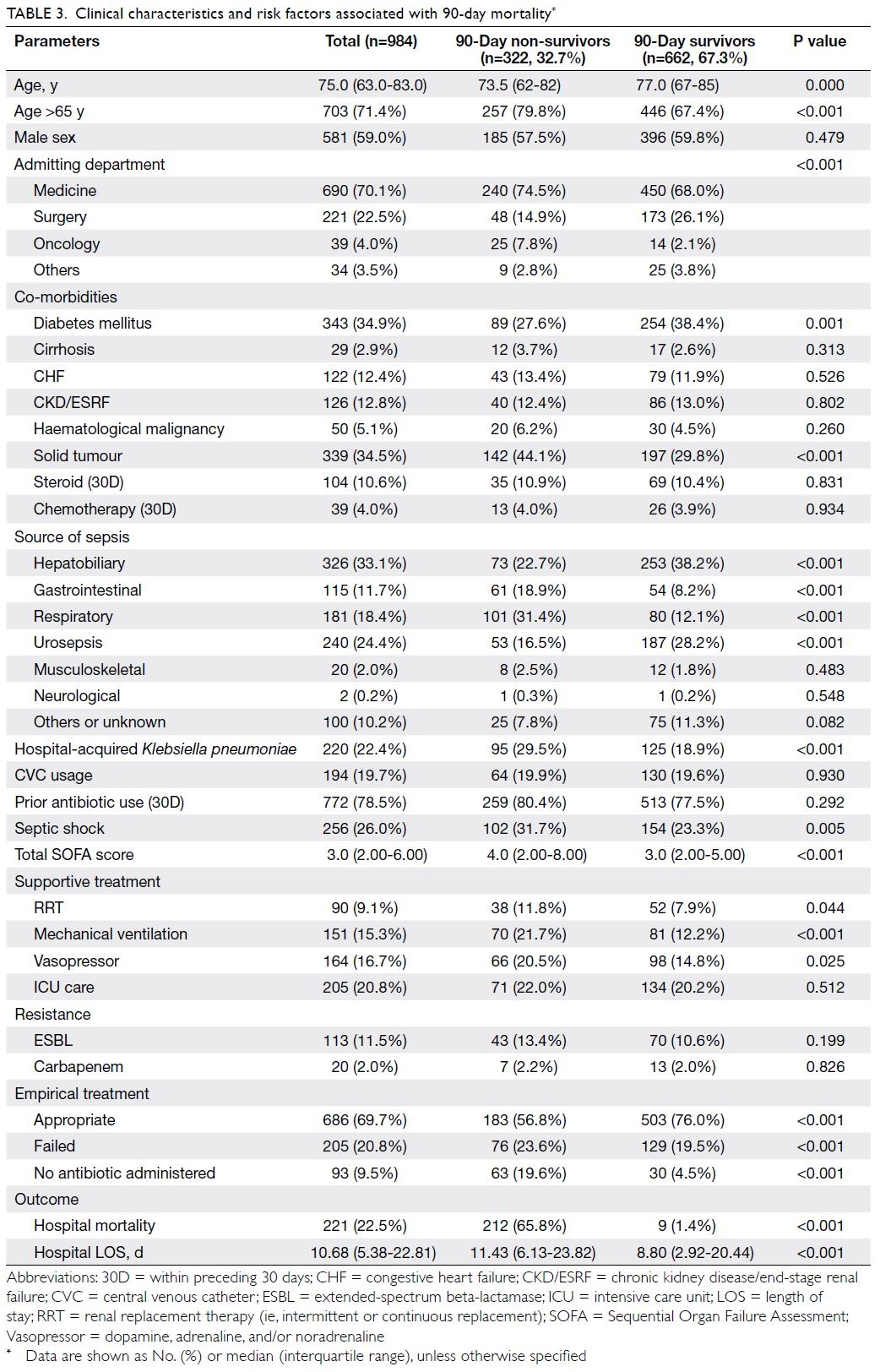

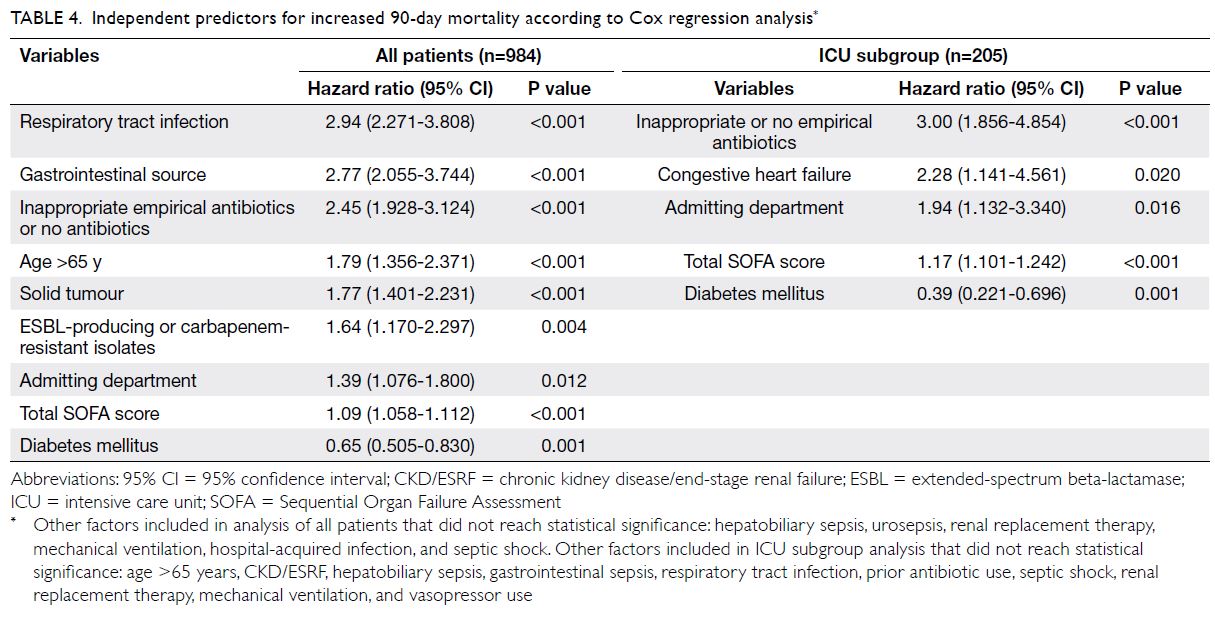

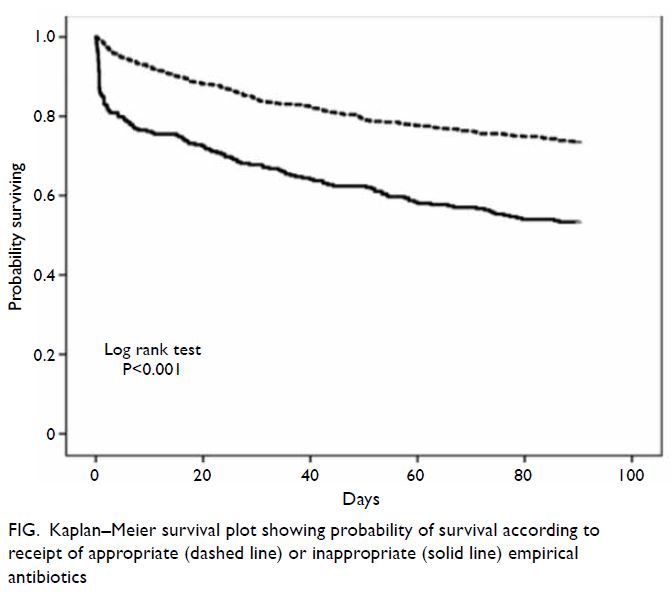

Figure. (a) Sports played among 720 hospitalised patients diagnosed with sports-related traumatic brain injury from 2015 to 2019. (b) Histogram depicting the number of patients with head injury because of cycling (grey bars) compared with those who had head injury because of other sports (white bars), according to age-group

Intracranial haemorrhage was noted in 283 (39.3%) patients with TBI; 166 (23.1%) patients

exhibited traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage and

157 (21.8%) exhibited ASDH. Skull fractures were

detected in 179 (24.9%) patients, with a median

Rotterdam CT score of 2 (interquartile range=2-2).

In total, 59 (8.2%) patients required neurosurgical

intervention; 32 (54.2%) of them had good recovery

with a median GOS score of 5 on discharge from

the hospital and at 6 months. The mean (± SD)

duration of hospitalisation was 5 ± 28 days. Among

307 (42.6%) patients in whom 6-month GOS scores

could be assessed, good recovery was observed in

260 (84.7%). Post-concussion syndrome was

diagnosed in 30 (6.2%) of 482 patients who attended

scheduled follow-up outpatient consultations.

Recreational cycling-related traumatic brain

injury

The crude incidence of recreational cycling-related

TBI requiring hospitalisation was 1.1 per 100 000

population. A comparison was performed between

cyclists with sports-related TBI and patients who had

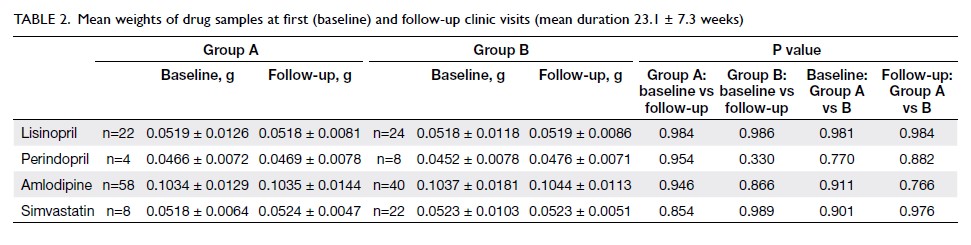

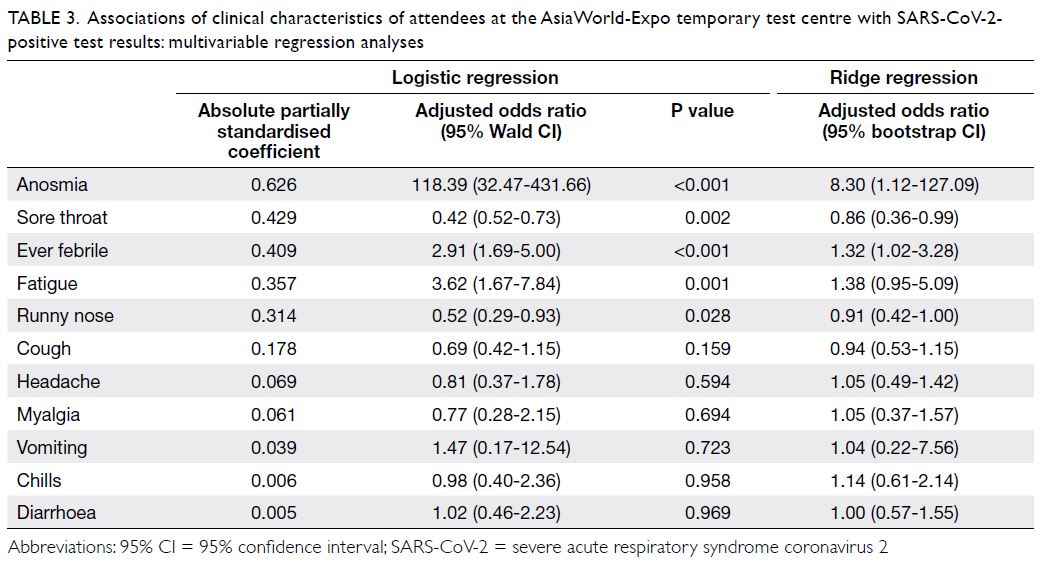

TBI because of other sports (Table 2). Cyclists were

significantly older (P<0.001) [Table 2; Fig b]. Among

426 cyclists, 306 (71.8%) were male and 120 (28.2%)

were female. However, the proportion of patients

who were female was significantly higher among

those who had TBI because of cycling (28.2%) than

among those who had TBI because of other sports (10.9%; P<0.001). Cyclists were likely to exhibit more

severe TBI with an almost three-fold greater risk of

sustaining extracranial injury (odds ratio [OR] 2.8;

95% CI: 1.9-4.0), resulting in a higher ISS (P<0.001).

Of cyclists admitted for head injury, 201 (47.2%) had

intracranial haemorrhage, which was radiologically

more extensive in terms of the Rotterdam CT

score, compared with haemorrhage in non-cyclists

(P<0.01). As a consequence, a greater proportion of

cyclists had a worse GOS score on discharge from

hospital (OR 2.8; 95% CI: 1.3-6.2) and at 6 months

(OR 4.7; 95% CI: 2.1-10.5). The cause of death for

all cyclists with 30-day mortality was severe TBI

with medically refractory intracranial hypertension.

Although the overall incidence was low, cyclists also

had a greater risk of post-concussion syndrome (OR

2.5; 95% CI: 1.2-5.4).

Table 2. Comparison of baseline characteristics and outcomes between cyclists and non-cyclists with sports-related traumatic brain injury

Predictors for traumatic intracranial

haemorrhage and poor functional outcome at

discharge from hospital among cyclists

Among the 426 cyclists in this study, 128 (30.0%)

experienced bicycle accidents during the weekend;

10 (2.3%) of the cyclists were professional athletes.

Most cyclists (273; 64.1%) accidently fell off their

bicycle on their own (ie, without colliding into

another object) on level ground. Of the injuries,

103 (24.2%) were sustained when the cyclist was

traveling downhill; for the 28 patients with records

of self-reported velocities, the estimated mean

(± SD) velocity at the moment before injury was

40 ± 15 km/h. At the time of injury, 361 (84.7%)

cyclists had not been wearing a helmet. Among eight

(1.9%) patients who subsequently died, none had

been wearing protective head gear.

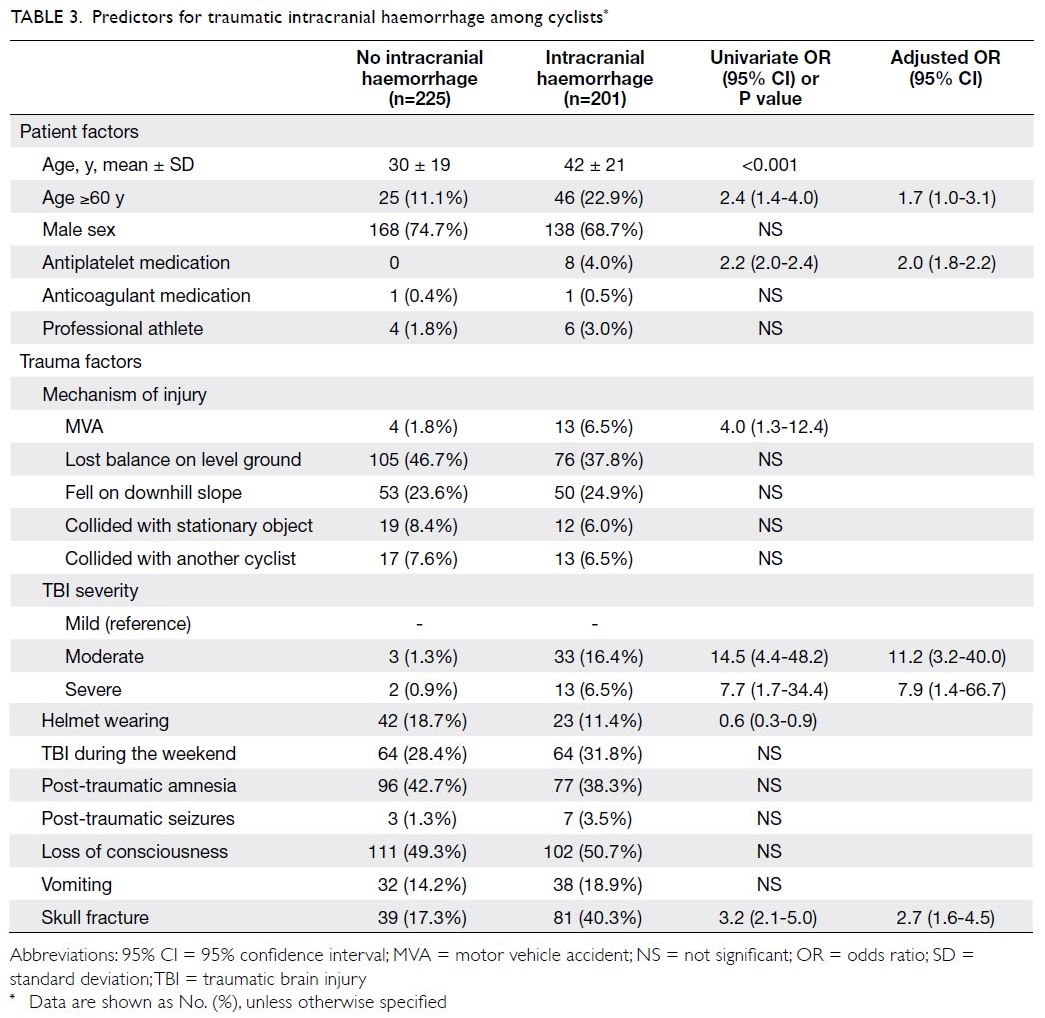

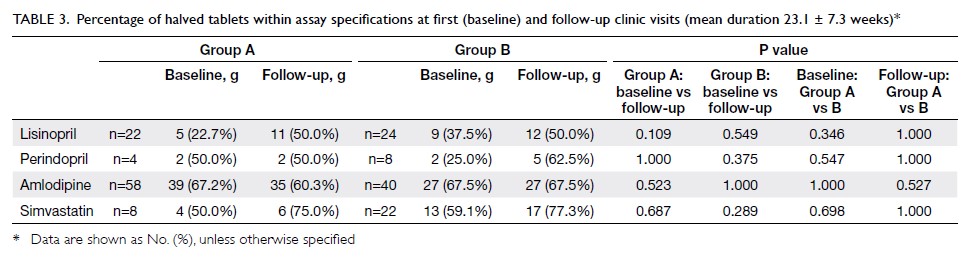

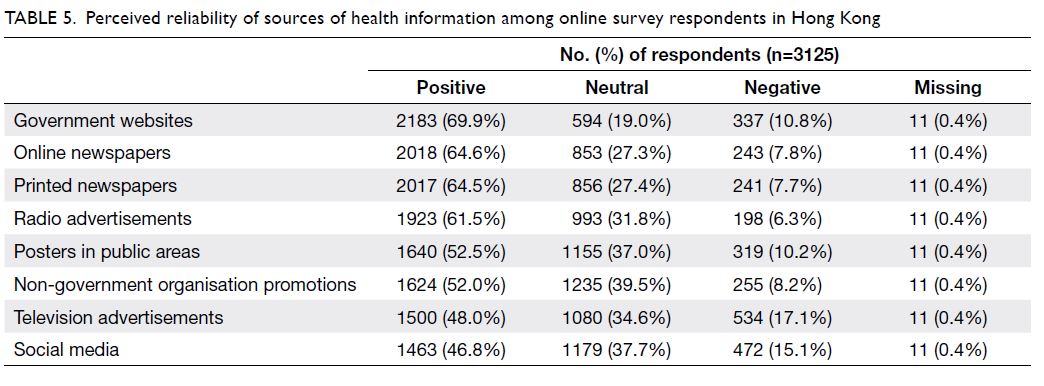

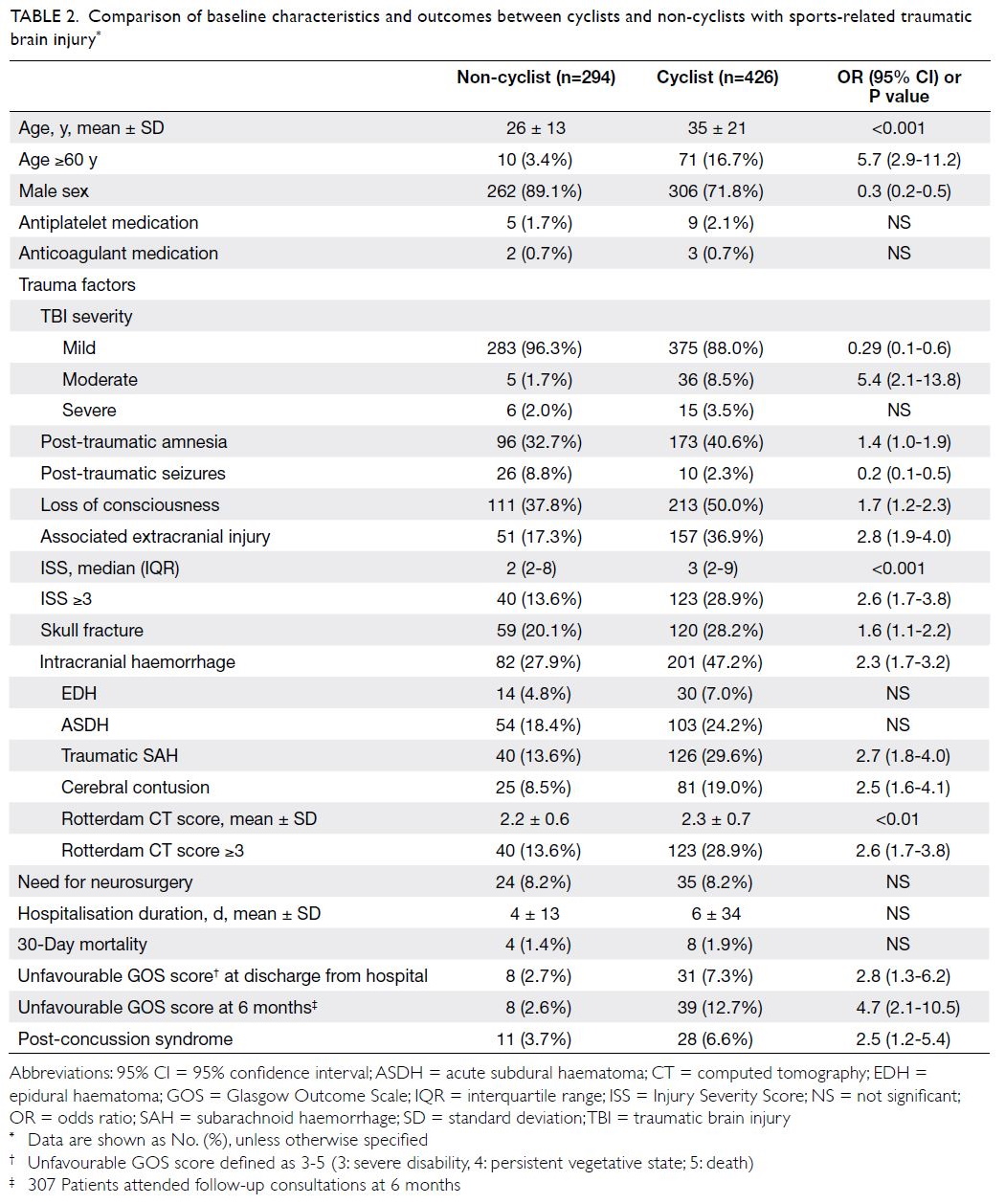

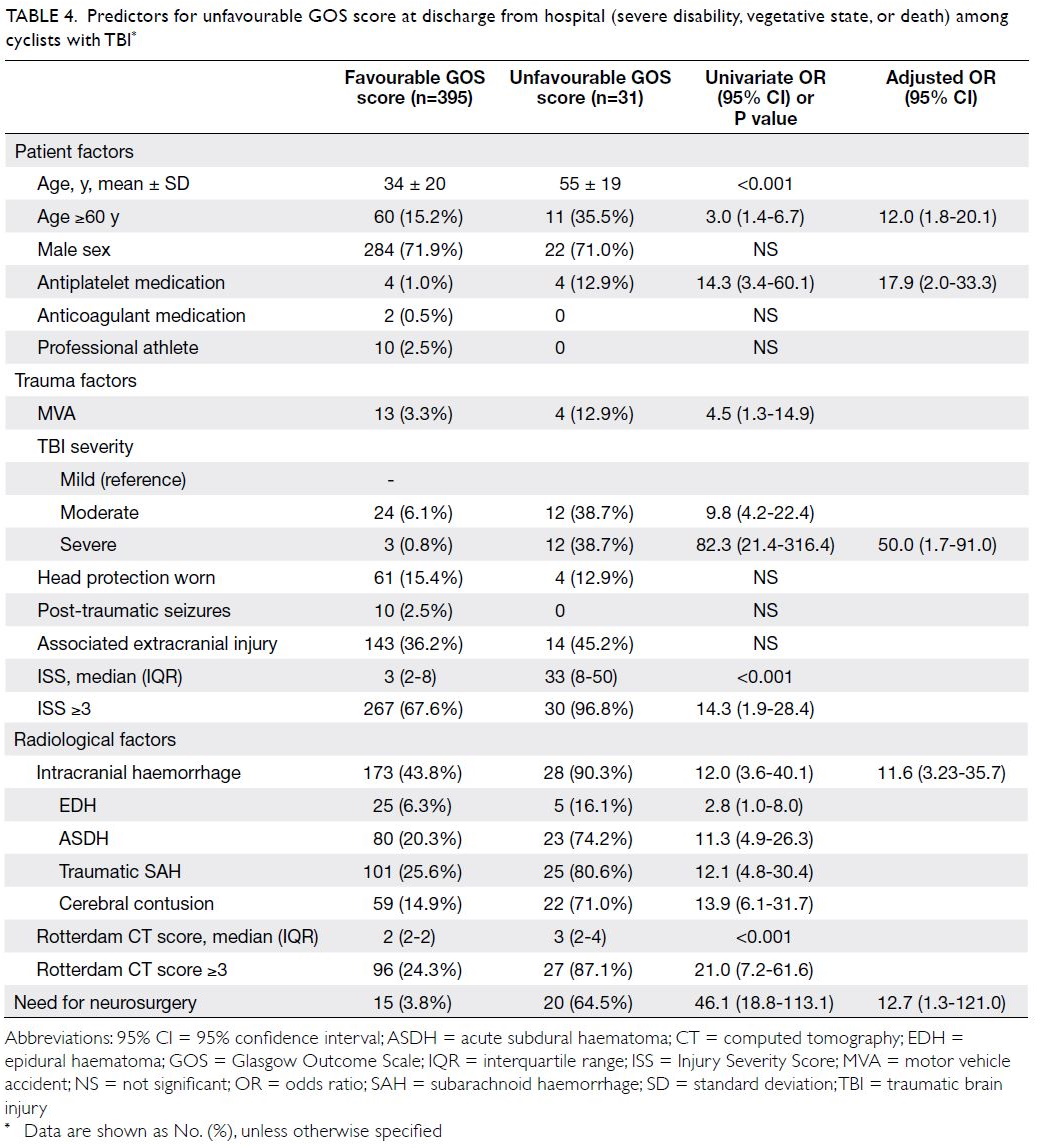

Risk factors for traumatic intracranial haemorrhage among cyclists are shown in Table 3.

Univariate analysis identified the following risk

factors: age ≥60 years, use of antiplatelet medication,

involvement in a motor vehicle collision, presence

of moderate to severe TBI, and skull fracture. In

univariate analysis, helmet wearing was protective

against intracranial haemorrhage. Multivariate

logistic regression identified the following

independent risk factors: age ≥60 years, antiplatelet

medication intake, moderate or severe TBI, and

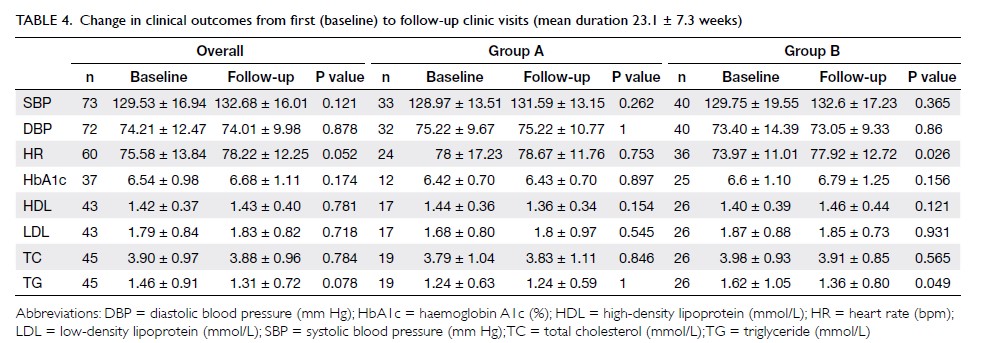

the presence of a skull fracture. Table 4 shows

independent significant predictors for unfavourable

GOS score on discharge from hospital: age ≥60 years,

antiplatelet intake, severe TBI, intracranial

haemorrhage, and the need for neurosurgical

operative intervention.

Table 4. Predictors for unfavourable GOS score at discharge from hospital (severe disability, vegetative state, or death) among cyclists with TBI

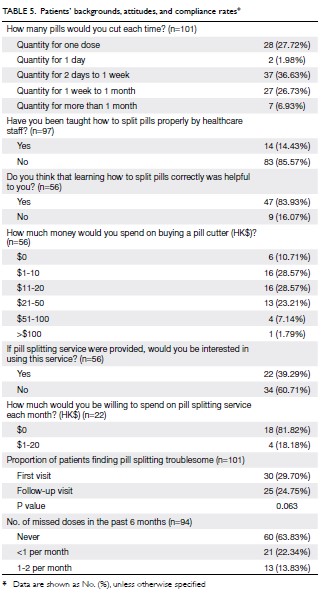

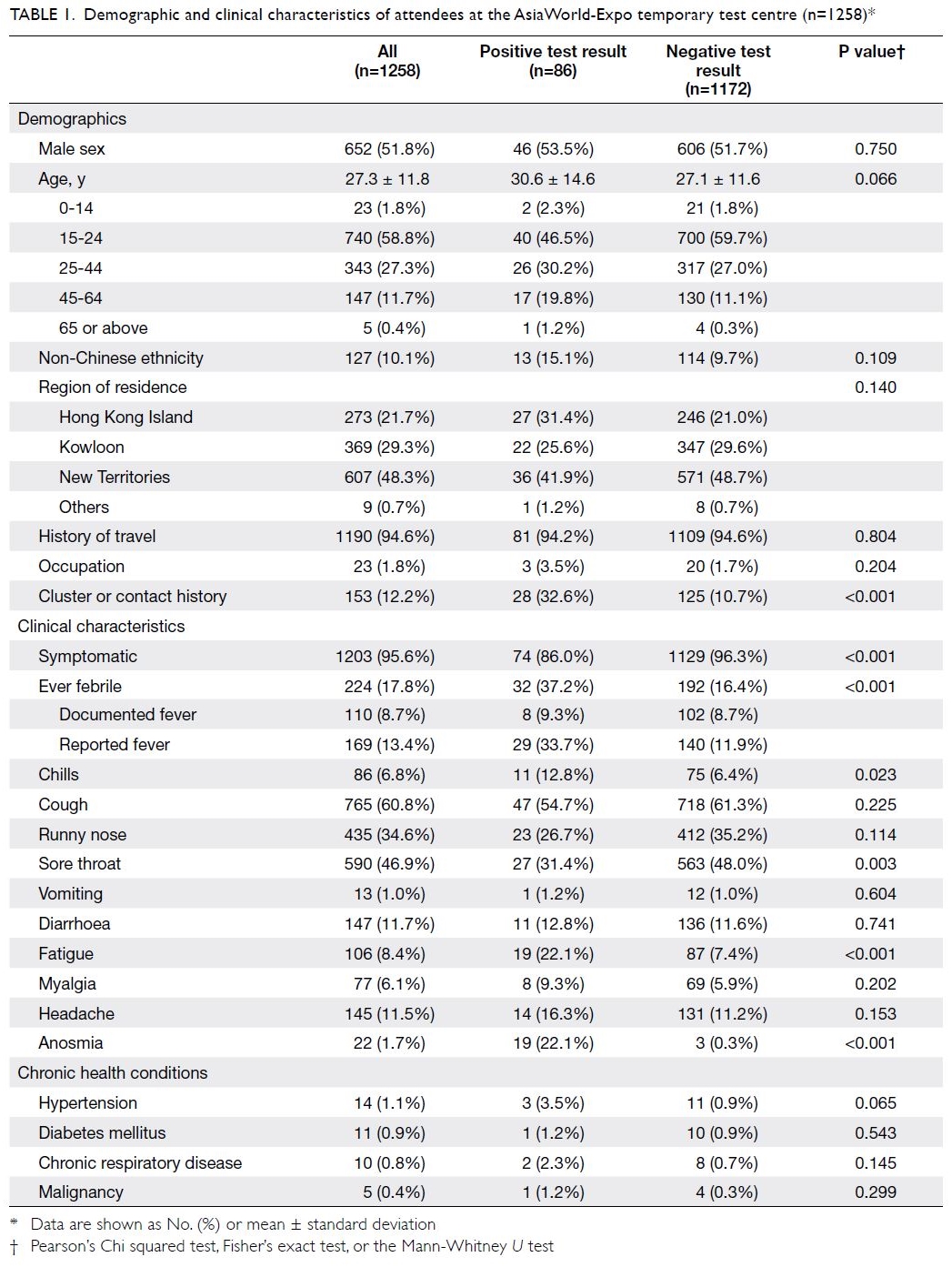

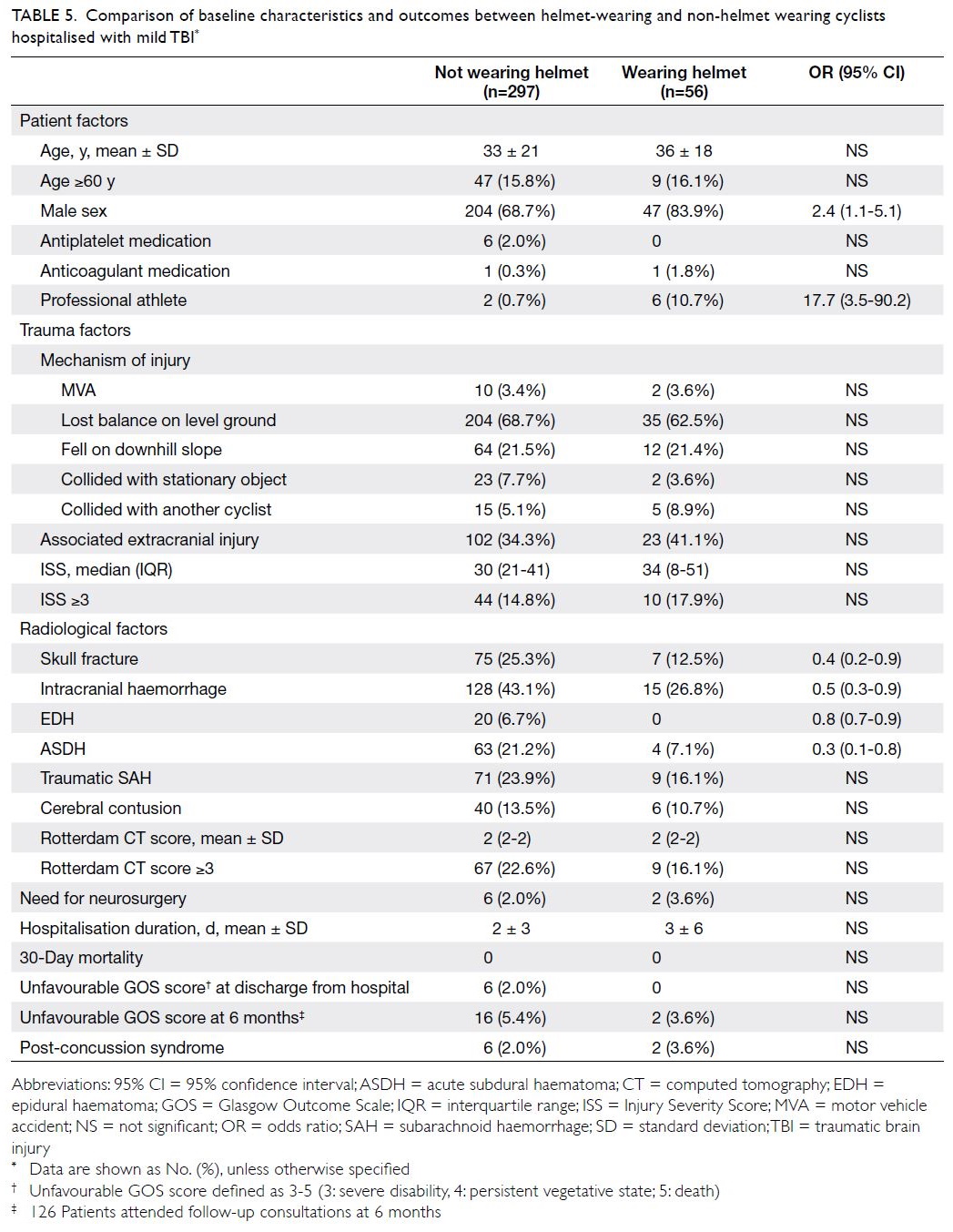

Effect of helmet use among cyclists

As shown in Table 2, 375 (88.0%) hospitalised cyclists had mild TBI, whereas only 36 (8.5%) cyclists

had moderate TBI and 15 (3.5%) had severe TBI. No protective effect of helmet use was noted in terms

of reducing TBI severity across these GCS-defined

categories (Table 3). However, among cyclists with

mild TBI, helmets were significantly protective

against intracranial haemorrhage and skull fracture,

regardless of age, antiplatelet medication intake, or

mechanism of injury (Table 5). Although the median

Rotterdam CT score was comparable between

cyclists with mild TBI who did or did not wear

helmets (P=0.68), significantly fewer patients with

head protection had epidural haematoma or ASDH.

For patients with mild TBI who had intracranial

haemorrhage, this difference in radiological factors led to a significantly shorter mean (± SD) duration

of hospitalisation for patients who wore helmets

(2.6 ± 2.9 days), compared with patients who did not

(7.1 ± 11.6 days, P<0.001). However, there was no

difference in the need for neurosurgical intervention

among patients with mild TBI who had intracranial

haemorrhage according to head protection status

(P=0.17). Similarly, unfavourable GOS scores on

discharge from hospital (P=0.43) and at 6 months

(P=0.71) were comparable among patients with mild TBI who had intracranial haemorrhage, regardless of

head protection status (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of baseline characteristics and outcomes between helmet-wearing and non-helmet wearing cyclists hospitalised with mild TBI

Discussion

Balancing sports engagement with sports-related

traumatic brain injury

The incidence of sports-related TBI in Hong Kong is 2 per 100 000 general population; this is lower

than in other countries (eg, the US, Australia, or Italy), where the incidences range from 4 to 32 per

100 000 population.12 The lower incidence in Hong

Kong is consistent with a previous finding that Hong

Kong residents (especially children and adolescents)

have lower physical activity and fitness levels than in

other regions, according to a global evidence-based

evaluation of such indicators from 49 countries.19

Considering the health benefits of an active lifestyle,

there is a clear need to promote sports engagement

in Hong Kong. A survey of 5701 residents performed

by the Transport Department of the Hong Kong SAR

Government estimated that 10% of households had

bicycles available for use; moreover, 69% (4 million)

of residents aged 15 years or older knew how to ride

one.16 In addition, most survey respondents (73%) cycled for recreational or fitness purposes.15

Cycling safety outcomes in Hong Kong

Previous epidemiological studies of sports-related

brain injuries revealed that cycling was one of the

most frequent activities involved.10 12 20 21 In 2019,

1738 road traffic accidents involving cyclists were

reported to the Hong Kong Transport Department.22

Half of these accidents (50.6%, 879/1738) occurred

in recreational areas such as cycling tracks, parks,

or playgrounds; eight (0.5%) patients experienced

fatal injuries.22 In the past 10 years, the number of

cyclist injuries in Hong Kong has increased by 5.2%

per year.17 Compared with other regions worldwide,

Hong Kong is one of the most dangerous areas

for cycling.17 The fatality rate (per billion minutes

cycled) in the city was 34, substantially higher than

the rates in Stockholm, Sweden (3), France (4), and other metropolitan areas (eg, New York City [18]

and Los Angeles [8]).17 These studies included riders

primarily involved in commuting and the causes

of death were not elucidated, but they indicate a

growing need to enhance the safety of vulnerable

road users.

To our knowledge, this is the first multicentre

study to comprehensively document the outcomes

of inpatients with recreational cycling-related TBI

using standard assessment criteria. By comparison

with patients who had TBI because of other sports,

we found that cyclists in Hong Kong exhibited greater risks of more severe injury, intracranial

haemorrhage, unfavourable GOS score at discharge

from hospital, and post-concussion syndrome.

Despite these findings, our results suggest that

cycling is generally safe and hospitalised patients had

a high (92.7%) likelihood of favourable functional

outcomes on discharge from hospital.

Single-centre reviews of cycling-related

injuries among various suburban districts in Hong

Kong found that limb injuries were the most

common form of trauma followed by head injury

(10%-39% of patients).23 24 25 26 Among patients with TBI, 16% to 53% exhibited “severe” injury; however, the

studies did not provide explicit definitions to qualify

this categorisation, and did not describe radiological

data regarding the extent of injury or the need

for neurosurgical intervention.23 26 In the present

study, 12% of hospitalised cyclists with head injury had moderate to severe TBI. There was also a high

incidence of intracranial haemorrhage involving

almost half of the patients. Both these factors were

independent predictors of poor GOS score on

discharge from hospital. Our results are consistent

with the findings in a previous study where 75% of all cycling-related deaths were caused by severe

TBI.27 The lack of an independent association with

motor vehicle collisions, which constituted only

a minority of injuries in this cohort, suggests that

recreational cycling at comparatively low speeds can

be fatal. Notably, the mechanism of injury for four

(50%) of the eight recreational cyclists who died in

this study was a loss of balance, followed by a fall on

level ground without colliding into another object,

person, or motor vehicle.

Helmet use: safety and legislative

implications

Previous studies in Hong Kong, the most recent of which was performed >10 years ago, revealed that recreational cyclists rarely wore protective headgear

(eg, frequencies of 0.2% to 2.2% among emergency

department attendees).24 25 26 Our findings revealed that

significantly more patients (15%) wore helmets at the

time of injury. Governmental advocacy initiatives for

promoting helmet wearing in recent years may have

resulted in heightened public awareness regarding

the risks of head trauma.28 There is little doubt

that helmets are protective. In the past 30 years,

several case-control and epidemiological studies

have delivered compelling evidence to support the

efficacy of bicycle helmet wearing in reducing the

risk of life-threatening TBI.29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 In a case-control

prospective multicentre study of over 3000 patients,

Thompson et al33 noted that helmets (irrespective

of design) conferred up to a 74% reduction in TBI

during accidents. A subsequent meta-analysis of five

studies observed that helmets provided a 63% to 88%

reduction in the risk of head, brain, and severe TBI

for all ages of cyclists; this included equal levels of

protection for collisions involving motor vehicles

and collisions due to other causes.38 In the present

study, helmet wearing did not reduce TBI severity

according to our broadly predefined categories.

However, among hospitalised recreational cyclists

with mild head injury, helmets did provide significant

protection against intracranial haemorrhage,

including potentially life-threatening epidural

haematomas and ASDHs, as well as skull fractures.

Thus, our findings may have important public health

implications with regard to introducing mandatory

bicycle helmet wearing legislation in the city.

Whether such laws should exist is a particularly

divisive issue among public health experts and

interest groups.39 40 41 42 43 In Australia, a nation with all-age

helmet wearing safety laws, an overall 46% decline

in cyclist fatalities per 1 000 000 population has been

reported, compared with the pre-legislation period.44

Similar findings were noted in New Zealand: a

67% decline in severe TBI was recorded after the

introduction of helmet laws.45 In the US, a significant

reduction in paediatric cyclist fatalities involving

motor vehicles was observed in states with such laws.46 A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of bicycle

helmet legislation revealed that it increased helmet

usage, while significantly reducing head injuries

and mortality.47 Several medical associations have

expressed support for introducing such legislation;

these include the World Health Organization, the

British Medical Association, the American Medical

Association, and the Royal Australasian College of

Surgeons.48 49 50 51 However, critics of such compulsory

policies have hypothesised that helmets could

encourage risk-compensation behaviour, whereby

cyclists may be more willing to engage in potentially

injurious risks or for motorists to exercise less

caution when encountering them.39 52 53 Other

reasons for opposition include infringement on

individual liberties; some public health scholars have

theorised that such laws could discourage cyclists

from participating in gainful physical activity.39 40 41 42 54

From a Hong Kong Transport Department survey

(5701 respondents) regarding attitudes towards

possible helmet law and enforcement measures, the

majority of respondents (78%-90%) were in favour of

introducing such legislation, especially when riding

on carriageways.16 However, among respondents

who knew how to ride a bicycle (3933 respondents),

23% declared they would ride less frequently if

mandatory helmet wearing was required.16

Limitations

An inherent limitation of a retrospective study of this

nature was the likely under-reporting of the number of

patients with sports-related head injuries. In the only

existing population-based study of TBI epidemiology

that included community-based injuries, 95% were

considered mild and 28% of respondents did not

seek medical attention.55 Among professional or

university-level athletes, under-reporting is more

apparent: questionnaire surveys reveal that 31% to

78% of respondents neglected to pursue medical

care despite experiencing a concussion during

the preceding 12 months.56 57 At the emergency

department level, no territory-wide TBI registry

exists in Hong Kong; moreover, diagnostic coding

to facilitate data retrieval is typically not performed

after consultations. Therefore, we could only identify

hospitalised patients with sports-related TBI by

means of an administrative database that utilised

the ICD-10 coding system. However, the validity

of such administrative data for research has been

questioned.58 Studies have shown significantly lower

TBI rates among young adults, men, and patients

with less severe injuries when the ICD system was

utilised, compared with thorough medical record

review.59 Analysis of a population-based TBI sample

showed that only 19% of individuals were assigned

a TBI-related diagnostic ICD code.60 In addition, a

degree of selection bias may have existed because

some non-hospitalised helmet-wearing cyclists with mild head injury may have been discharged from the

emergency department, mitigating the protective

effects of helmet use. This may explain why no

considerable differences in outcomes were detected

for patients with moderate or severely injured

patients. Despite the low rate of helmet use among

recreational cyclists (15%), significant protective

effects were detected among mildly injured patients

with regard to intracranial haemorrhage and skull

fracture. This limited participant identification

approach also allowed for a pragmatic review of

patients with clinically significant TBI who were

hospitalised following evaluation by an emergency

care physician. Computed tomography scans are

generally performed only for hospitalised patients

with head injury in our public healthcare system;

this approach offered an opportunity to evaluate

imaging data for intracranial haemorrhage. Because

the ICD coding system for traumatic intracranial

haemorrhage reportedly has high sensitivity and

specificity (both >80%),59 we adopted this coding

outcome as the study’s primary endpoint. Another

important limitation was the definition of mild

TBI, which affected most patients in this study. The

definitions offered by several authorities range from

conventional GCS-based criteria such as the US

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,61 and

the American College of Surgeons62 to additional

symptoms of confusion, memory impairment,

transient loss of consciousness, and irritability

proposed by the World Health Organisation and the

American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine.18 63 64

A better delineation of these symptoms would have

enhanced the identification of patients with “high-risk”

mild TBI; however, because these relevant

symptoms were often not systematically documented

in most medical records retrieved in our study, we

used GCS-based criteria to reduce the overall rate of

underdiagnosis. Using GOS score on discharge from

hospital as a secondary study endpoint, we found that

only 31 (7%) patients had unfavourable outcomes.

Although statistically significant predictors for TBI

were identified, the wide confidence intervals for

these predictors suggest that the sample size was

insufficient to draw robust conclusions. Finally, we

could only retrospectively assess GOS score as a

fundamental measure of functional outcome. More

sensitive instruments (eg, the extended GOS or

the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool65 66) might

have been better for assessing the psychosocial and

cognitive aspects of TBI, considering that a large

proportion of mildly injured cyclists had intracranial

haemorrhage.

Conclusions

The incidence of sports-related TBI in Hong Kong is low and cycling is the most frequently associated activity. Almost half of hospitalised recreational cyclists sustained intracranial haemorrhage.

Compared with patients who had head injury

because of other sports, cyclists are more likely to

experience severe consequences. There is evidence

that helmet use offers protection against intracranial

haemorrhage and skull fracture among cyclists

with mild head injury. Cycling is a safe physical

activity, but further legislative measures should be

introduced to promote and protect the welfare of

individuals enjoying this sport.

Author contributions

Concept or design: PYM Woo, E Cheung.

Acquisition of data: PYM Woo, E Cheung, FWY Lau, NWS Law, CKY Mak, P Tan, B Siu, A Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PYM Woo, E Cheung, CKY Mak.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: PYM Woo, E Cheung, FWY Lau, NWS Law, CKY Mak, P Tan, B Siu, A Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PYM Woo, E Cheung, CKY Mak.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

This research has not been presented or published in any form prior to submission.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Kowloon Central Cluster/Kowloon East Cluster research ethics committee (Ref KCC/KEC-2020-0331). All patients were treated in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained

from either the patient, next-of-kin, or their legal guardian.

References

1. Allender S, Cowburn G, Foster C. Understanding

participation in sport and physical activity among children

and adults: a review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res

2006;21:826-35. Crossref

2. Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ 2006;174:801-9. Crossref

3. Batty D, Thune I. Does physical activity prevent cancer?

Evidence suggests protection against colon cancer and

probably breast cancer. BMJ 2000;321:1424-5. Crossref

4. Batty GD, Lee IM. Physical activity and coronary heart disease. BMJ 2004;328:1089-90. Crossref

5. Aune D, Norat T, Leitzmann M, Tonstad S, Vatten LJ. Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol

2015;30:529-42. Crossref

6. Liu X, Zhang D, Liu Y, et al. Dose-response association between physical activity and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies.

Hypertension 2017;69:813-20. Crossref

7. Malm C, Jakobsson J, Isaksson A. Physical activity and

sports-real health benefits: a review with insight into the

Public Health of Sweden. Sports (Basel) 2019;7:127. Crossref

8. Puckett M, Neri A, Underwood JM, Stewart SL. Nutrition and physical activity strategies for cancer prevention in current national comprehensive cancer control program

plans. J Community Health 2016;41:1013-20. Crossref

9. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Towards 2025: strategy and action plan to prevent and

control non-communicable diseases in Hong Kong.

2018 Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/saptowards2025_fullreport_en.pdf. Accessed 2 Aug 2020.

10. Theadom A, Starkey NJ, Dowell T, et al. Sports-related brain injury in the general population: an epidemiological study. J Sci Med Sport 2014;17:591-6. Crossref

11. Manley G, Gardner AJ, Schneider KJ, et al. A systematic

review of potential long-term effects of sport-related

concussion. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:969-77. Crossref

12. Theadom A, Mahon S, Hume P, et al. Incidence of sports-related

traumatic brain injury of all severities: a systematic

review. Neuroepidemiology 2020;54:192-9. Crossref

13. Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC, Cantu RC. The epidemiology of sport-related concussion. Clin Sports

Med 2011;30:1-17. Crossref

14. Selassie AW, Wilson DA, Pickelsimer EE, Voronca DC,

Williams NR, Edwards JC. Incidence of sport-related

traumatic brain injury and risk factors of severity: a

population-based epidemiologic study. Ann Epidemiol

2013;23:750-6. Crossref

15. Transport Department, Hong Kong SAR Government. Cycling study. 2004. Available from: https://www.td.gov.hk/filemanager/en/publication/cyclingstudy.pdf. Accessed 22 Aug 2020.

16. Transport Department. Hong Kong SAR Government.

Travel Characteristics Survey 2011 Final Report.

Available from: https://www.td.gov.hk/filemanager/en/content_4652/tcs2011_eng.pdf. Accessed 22 Aug 2020.

17. Xu P, Dong N, Wong SC, Huang H. Cyclists injured in

traffic crashes in Hong Kong: a call for action. PLoS One

2019;14:e0220785. Crossref

18. Servadei F, Teasdale G, Merry G, Neurotraumatology

Committee of the World Federation of Neurosurgical

Societies. Defining acute mild head injury in adults: a

proposal based on prognostic factors, diagnosis, and

management. J Neurotrauma 2001;18:657-64. Crossref

19. Huang WY, Wong SH, Sit CH, et al. Results from the Hong Kong’s 2018 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J Exerc Sci Fit 2019;17:14-9. Crossref

20. Harris AW, Jones CA, Rowe BH, Voaklander DC. A

population-based study of sport and recreation-related

head injuries treated in a Canadian health region. J Sci Med

Sport 2012;15:298-304. Crossref

21. Beck AJ, Kee J. The epidemiology of sports head injuries in a rural population. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:A20. Crossref

22. Transport Department, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Road Traffic Accident Statistics. Year 2019. Road traffic

accidents involving bicycle by location and severity

2019. Available from: https://www.td.gov.hk/en/road_safety/road_traffic_accident_statistics/2019/index.html. Accessed 9 Aug 2020.

23. Lee LL, Yeung KL, Chan JT, Chen RC. A profile of bicycle-related injuries in Tai Po. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 2003;10:81-7.Crossref

24. Yeung JH, Leung CS, Poon WS, Cheung NK, Graham CA,

Rainer TH. Bicycle related injuries presenting to a trauma

centre in Hong Kong. Injury 2009;40:555-9. Crossref

25. Ng CP, Siu AY, Chung CH. Bicycle-related injuries: a local scene. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 2001;8:78-83. Crossref

26. Sze NN, Tsui KL, Wong SC, So FL. Bicycle-related crashes in Hong Kong: is it possible to reduce mortality and severe

injury in the metropolitan area? Hong Kong J Emerg Med

2011;18:136-43. Crossref

27. Rivara FP, Thompson DC, Thompson RS. Epidemiology of bicycle injuries and risk factors for serious injury. Inj Prev 1997;3:110-4. Crossref

28. Transport Department, Hong Kong SAR Government. Be a smart cyclist. Wear bicycle helmet always. 2020.

Available from: https://www.td.gov.hk/filemanager/en/content_4551/221201047_leaflet_a.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2020.

29. Attewell RG, Glase K, McFadden M. Bicycle helmet efficacy: a meta-analysis. Accid Anal Prev 2001;33:345-52. Crossref

30. Maimaris C, Summers CL, Browning C, Palmer CR. Injury

patterns in cyclists attending an accident and emergency

department: a comparison of helmet wearers and non-wearers.

BMJ 1994;308:1537-40. Crossref

31. McDermott FT, Lane JC, Brazenor GA, Debney EA. The effectiveness of bicyclist helmets: a study of 1710 casualties. J Trauma 1993;34:834-44. Crossref

32. Thomas S, Acton C, Nixon J, Battistutta D, Pitt WR, Clark R.

Effectiveness of bicycle helmets in preventing head injury

in children: case-control study. BMJ 1994;308:173-6. Crossref

33. Thompson DC, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Effectiveness of bicycle safety helmets in preventing head injuries. A case-control

study. JAMA 1996;276:1968-73. Crossref

34. Thompson RS, Rivara FP, Thompson DC. A case-control study of the effectiveness of bicycle safety helmets. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1361-7. Crossref

35. Strotmeyer SJ, Behr C, Fabio A, Gaines BA. Bike helmets

prevent pediatric head injury in serious bicycle crashes

with motor vehicles. Inj Epidemiol 2020;7(Suppl 1):24. Crossref

36. Sethi M, Heidenberg J, Wall SP, et al. Bicycle helmets are

highly protective against traumatic brain injury within a

dense urban setting. Injury 2015;46:2483-90. Crossref

37. Persaud N, Coleman E, Zwolakowski D, Lauwers B, Cass D.

Nonuse of bicycle helmets and risk of fatal head injury:

a proportional mortality, case-control study. CMAJ

2012;184:E921-3. Crossref

38. Thompson DC, Rivara FP, Thompson R. Helmets for

preventing head and facial injuries in bicyclists. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2000;1999(2):CD001855. Crossref

39. Robinson DL. No clear evidence from countries that have enforced the wearing of helmets. BMJ 2006;332:722-5. Crossref

40. Hong Kong Cycling Alliance. Helmets. Available from:

http://hkcyclingalliance.org/on-the-road/helmets. Accessed 21 Aug 2020.

41. Bateman-House A. Bikes, helmets, and public health: decision-making when goods collide. Am J Public Health 2014;104:986-92. Crossref

42. Goldacre B, Spiegelhalter D. Bicycle helmets and the law. BMJ 2013;346:f3817. Crossref

43. Rivara FP, Thompson DC, Patterson MQ, Thompson RS.

Prevention of bicycle-related injuries: helmets, education,

and legislation. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19:293-318. Crossref

44. Olivier J, Boufous S, Grzebieta R. The impact of bicycle helmet legislation on cycling fatalities in Australia. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48:1197-203. Crossref

45. Tin Tin S, Woodward A, Ameratunga S. Injuries to pedal cyclists on New Zealand roads, 1988-2007. BMC Public

Health 2010;10:655. Crossref

46. Meehan WP 3rd, Lee LK, Fischer CM, Mannix RC. Bicycle helmet laws are associated with a lower fatality rate from bicycle-motor vehicle collisions. J Pediatr 2013;163:726-9. Crossref

47. Macpherson A, Spinks A. Bicycle helmet legislation for the uptake of helmet use and prevention of head injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;2008(3):CD005401. Crossref

48. World Health Organisation. Why are helmets needed?

2006. Available from: https://www.who.int/roadsafety/projects/manuals/helmet_manual/1-Why.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2021.

49. British Medical Association. Healthy transport=healthy

lives. 2012. Available from: https://thepep.unece.org/sites/default/files/2017-06/Healthy%20transport%20healthy%20lives%20Britsh%20Medical%20Association.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2021.

50. American Medical Association. Helmets for riders of

motorized and non-motorized cycles H-10.964. Available

from: https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/bicycle helmets?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-3.xml. Accessed 20 Sep 2021.

51. McDermott FT. Helmet efficacy in the prevention of

bicyclist head injuries: Royal Australasian College of

Surgeons initiatives in the introduction of compulsory

safety helmet wearing in Victoria, Australia. World J Surg

1992;16:379-83. Crossref

52. Gamble T, Walker I. Wearing a bicycle helmet can increase

risk taking and sensation seeking in adults. Psychol Sci

2016;27:289-94. Crossref

53. Walker I. Drivers overtaking bicyclists: objective data on

the effects of riding position, helmet use, vehicle type and

apparent gender. Accid Anal Prev 2007;39:417-25. Crossref

54. Hooper C, Spicer J. Liberty or death; don’t tread on me. J

Med Ethics 2012;38:338-41. Crossref

55. Theadom A, Barker-Collo S, Feigin VL, et al. The spectrum

captured: a methodological approach to studying incidence

and outcomes of traumatic brain injury on a population

level. Neuroepidemiology 2012;38:18-29. Crossref

56. Delaney JS, Lamfookon C, Bloom GA, Al-Kashmiri A,

Correa JA. Why university athletes choose not to reveal

their concussion symptoms during a practice or game. Clin

J Sport Med 2015;25:113-25. Crossref

57. Meehan WP 3rd, Mannix RC, O’Brien MJ, Collins MW.

The prevalence of undiagnosed concussions in athletes.

Clin J Sport Med 2013;23:339-42. Crossref

58. van Walraven C, Bennett C, Forster AJ. Administrative

database research infrequently used validated diagnostic

or procedural codes. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1054-9. Crossref

59. Carroll CP, Cochran JA, Guse CE, Wang MC. Are we

underestimating the burden of traumatic brain injury?

Surveillance of severe traumatic brain injury using Centers

for Disease Control International Classification of Disease,

Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, traumatic brain

injury codes. Neurosurgery 2012;71:1064-70. Crossref

60. Barker-Collo S, Theadom A, Jones K, Feigin VL, Kahan M.

Accuracy of an International Classification of Diseases

Code Surveillance System in the identification of traumatic

brain injury. Neuroepidemiology 2016;47:46-52. Crossref

61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Glasgow

Coma Scale. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/masstrauma/resources/gcs.pdf. Accessed 20 Sep 2021.

62. American College of Surgeons. Best practices in the

management of traumatic brain injury. Available from:

https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/tbi_guidelines.ashx. Accessed 20 Sep 2021.

63. Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Holm L, Kraus J, Coronado VG,

WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic

Brain Injury. Methodological issues and research

recommendations for mild traumatic brain injury: the

WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic

Brain Injury. J Rehabil Med 2004;(43 Suppl):113-25. Crossref

64. Kay T, Harrington DE, Adams R, et al. Definition of mild

traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1993;8:86-7. Crossref

65. Kean J, Malec JF. Towards a better measure of brain injury outcome: new measures or a new metric? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:1225-8. Crossref

66. McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus

statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International

Conference on Concussion in Sport, Zurich, November

2012. J Athl Train 2013;48:554-75. Crossref