Hong Kong Med J 2020 Oct;26(5):382–9 | Epub 8 Oct 2020

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Comparison of carbetocin and oxytocin infusions

in reducing the requirement for additional

uterotonics or procedures in women at increased

risk of postpartum haemorrhage after

Caesarean section

KY Tse, MB, BS, MRCOG; Florrie NY Yu, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); KY Leung, FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KY Tse (barontse@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Postpartum haemorrhage is a major

cause of maternal mortality and morbidity, commonly

due to uterine atony. Prophylactic oxytocin use

during Caesarean section is recommended; patients

with a high risk of postpartum haemorrhage may

require additional uterotonics or procedures.

Carbetocin is a long-acting analogue of oxytocin

which has shown beneficial results, compared with

oxytocin. This study compared the requirement for

additional uterotonics or procedures between at-risk

women who underwent carbetocin infusion and

those who underwent oxytocin infusion.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study included

women at increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage

after Caesarean section for various indications

in a public hospital. Women who received carbetocin

infusion and women who received oxytocin infusion

were compared, stratified by Caesarean section

timing (elective or emergency). The primary outcome

was the requirement for additional uterotonic agents

or procedures. Secondary outcomes included total

blood loss, operating time, rate of postpartum

haemorrhage, need for blood transfusion, and need

for hysterectomy.

Results: Of 1236 women included in the study, 752

received oxytocin first and 484 received carbetocin

first. The two groups had comparable blood loss,

operating time, rate of postpartum haemorrhage,

requirement for additional uterotonics or

procedures, need for blood transfusion, and need

for hysterectomy. There was a reduction in the

requirement for additional uterotonics or procedures,

and in the rate of postpartum haemorrhage for

women with major placenta praevia or with multiple

pregnancies, following receipt of carbetocin first.

Conclusion: Compared with oxytocin, carbetocin

can reduce the requirement for additional uterotonics

or procedures in selected high-risk patient groups.

New knowledge added by this study

- The use of carbetocin reduced the requirement for additional uterotonics or procedures in women with major placenta praevia and in women with multiple pregnancies.

- Infusions of carbetocin and oxytocin had differential effects on the requirement for additional uterotonics or procedures in women who underwent Caesarean section for different indications.

- Women who received carbetocin infusion had similar blood loss, operating time, rate of postpartum haemorrhage, requirement for additional uterotonics or procedures, need for blood transfusion, and need for hysterectomy, compared with women who received oxytocin infusion.

- Carbetocin may be appropriate for women undergoing Caesarean section for major placenta praevia or multiple pregnancies.

- Oxytocin may be appropriate for women undergoing Caesarean section for other indications.

- There is a need to investigate the cost-effectiveness of carbetocin, which will aid clinicians in treatment selection.

Introduction

Postpartum haemorrhage is the major cause of

maternal death and morbidity worldwide,1 commonly

due to uterine atony (approximately 70% of cases).2 This type of haemorrhage is defined as blood loss of at

least 500 mL after vaginal delivery and blood loss of

>1000 mL after Caesarean section.3 Oxytocin (with or

without ergometrine) is the current standard therapy for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage; it is a

peptide hormone secreted by the posterior pituitary

gland, which stimulates myometrial contraction

in the second and third stages of labour. However,

failure of postpartum haemorrhage prophylaxis with

oxytocin (as demonstrated by the need for a rescue

uterotonic) occurs commonly, necessitating the use

of further oxytocin or other treatments to maintain

haemodynamic stability.4

Carbetocin is a synthetic analogue of oxytocin

which has a longer half-life than oxytocin, thus

reducing the requirement for an infusion after the

initial dose. This difference in structure, compared

with oxytocin, makes carbetocin more stable;

thus, carbetocin can avoid early decomposition by

disulfidase, aminopeptidase, and oxidoreductase

enzymes. Compared with oxytocin, carbetocin

induces a prolonged uterine response, in terms of

both amplitude and frequency of contractions, when

administered postpartum.5

A Cochrane review in 2012 found that

carbetocin reduced the use of additional uterotonics

and uterine massage, when compared with oxytocin.3

In 2018, a meta-analysis involving seven trials

showed that carbetocin was effective in reducing the

use of additional uterotonics, as well as in reducing

postpartum haemorrhage and transfusion, when

used during Caesarean section.6 A recent meta-analysis

involving 30 trials has shown that carbetocin

is effective in reducing the need for additional uterotonic use and postpartum blood transfusion in

women at increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage

after Caesarean delivery.7 Another recent

meta-analysis involving nine trials has shown that

carbetocin is associated with a 53% reduction in the

need for additional uterotonics, when compared with

oxytocin, at the time of elective Caesarean delivery.8

The use of carbetocin has been recommended in

elective Caesarean sections by the Royal College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists9 and the Society of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada.10

In one meta-analysis,6 heterogeneity was found

in the use of dose of oxytocin, which ranged from 2 IU

to 10 IU of bolus oxytocin to infusions of 20 to 30 IU,

and in the indications for Caesarean section. In a study

of 1568 Chinese women who underwent Caesarean

section for different indications, carbetocin and

oxytocin were found to have differential effects on

postpartum haemorrhage and related changes.6

However, to the best of our knowledge, most studies

have compared the differential therapeutic effects of

carbetocin and oxytocin in the general population or

in low-risk groups. Carbetocin is a relatively more

expensive drug than conventional synthetic oxytocin

(eg, Syntocinon), and there has not been sufficient

evidence from cost-effectiveness studies to support

its use in all patients. The use of carbetocin is therefore

limited to certain high-risk populations in some

institutions, including our hospital. The aim of the

present study was to compare effectiveness between

carbetocin and oxytocin in terms of reducing the

requirement for additional uterotonics in women at

increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage after

Caesarean section.

Methods

This study was conducted at the Department of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, Hong Kong, from 1 January 2016 to 30

June 2019; during this period, 5994 pregnant women

underwent Caesarean section in our hospital.

Demographic characteristics, obstetric histories,

risk factors, and perinatal outcomes were collected.

The study was approved by the Hospital Authority

Research Ethics Committee (Kowloon Central/Kowloon East) [KC/KE-20-0073/ER-1].

The inclusion criteria were women who

underwent Caesarean section for live birth after

24 weeks of completed gestation during the

aforementioned time period, with high risk of

developing postpartum haemorrhage (including

placenta praevia, presence of uterine fibroids,

multiple pregnancies, polyhydramnios, and

macrosomia), excluding patients with low risk

(n=4758, of whom 96 had low risk but received

oxytocin and carbetocin after identification of

postpartum haemorrhage). Patients who received

both oxytocin and carbetocin were assigned to the group where the first drug (oxytocin or carbetocin)

was used for prevention of postpartum haemorrhage,

then considered to require additional uterotonics

(carbetocin or oxytocin).

In our hospital, the implementation of

carbetocin began in April 2017. Prior to the

implementation of carbetocin, women who

were presumed to have a low risk of postpartum

haemorrhage were administered 10 IU oxytocin

intravenous bolus after delivery of the baby during

Caesarean section; women who were presumed to

have a high risk of postpartum haemorrhage were

administered 40 IU oxytocin intravenous infusion

over the course of 5 hours for a longer protective

effect. Depending on the clinical response,

further infusion of oxytocin might be indicated.

Following the implementation of carbetocin, we

have revised our protocol to administer the drug

100 μg intravenously over 1 minute for a single

dose after delivery of the baby, for women with

a high risk of postpartum haemorrhage (ie, with

the aforementioned risk factors) or for women

who required such treatment in accordance with

the obstetrician’s judgement. Contra-indications

included hypersensitivity to carbetocin, timing

prior to delivery of the baby, vascular disease

(especially coronary artery disease), and hepatic

or renal disease. The use of blood transfusion,

additional uterotonic agents (eg, carboprost 250 μg

intramuscularly or intramyometrially, misoprostol

800 μg rectally, oxytocin infusion after carbetocin,

or carbetocin after oxytocin infusion), obstetric

balloon tamponade, compression suture, uterine

artery embolisation, uterine artery ligation, or

hysterectomy was based on the control of postpartum

haemorrhage and the patient’s vital signs, as well as

the attending obstetrician’s judgement.

In this study, we subdivided the patients

according to risk factors. We then analysed each

patient group separately: patients who underwent

elective Caesarean section (ie, those who underwent

Caesarean section before labour onset) versus

patients who underwent emergency Caesarean

section (ie, those who either underwent intrapartum

Caesarean section, or who underwent Caesarean

section prior to the scheduled elective date for

reasons such as heavy antepartum haemorrhage).

The primary outcome was the requirement

for additional uterotonic agents or haemostatic

procedures (carboprost, misoprostol, oxytocin

infusion after carbetocin, carbetocin after oxytocin

infusion, obstetric balloon tamponade, uterine artery

embolisation, or uterine artery ligation). Secondary

outcomes were estimated blood loss, rate of

postpartum haemorrhage, operating time, the need

for blood transfusion, and the need for hysterectomy.

Blood loss was estimated by measuring the volume

within the suction bottle and the uptake in surgical drapes, pads, and gauzes. Postpartum haemorrhage

was defined as blood loss >1000 mL during or

immediately after the operation.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM

SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], United States). Continuous variables

were expressed as the mean±standard deviation and

compared by Student’s t test. Qualitative data were

expressed as number (percentage) and compared by

the Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test. A P value of

<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Linear

regression and multiple logistic regression were used

to control for potential confounding factors when

assessing the associations of carbetocin treatment

with primary outcomes. Potential confounding

factors included age, parity, fetal body weight,

gestation, and order of pregnancy. Unstandardised

regression coefficients, adjusted odds ratios, and

associated 95% confidence intervals were calculated

to estimate relative risk.

Results

Of 5994 pregnant women who underwent Caesarean

sections during the study period, 4758 were excluded

because they were at low risk of postpartum

haemorrhage. Of the remaining 1236 women who

met the criteria for inclusion in the study, 752

received oxytocin first and 484 received carbetocin

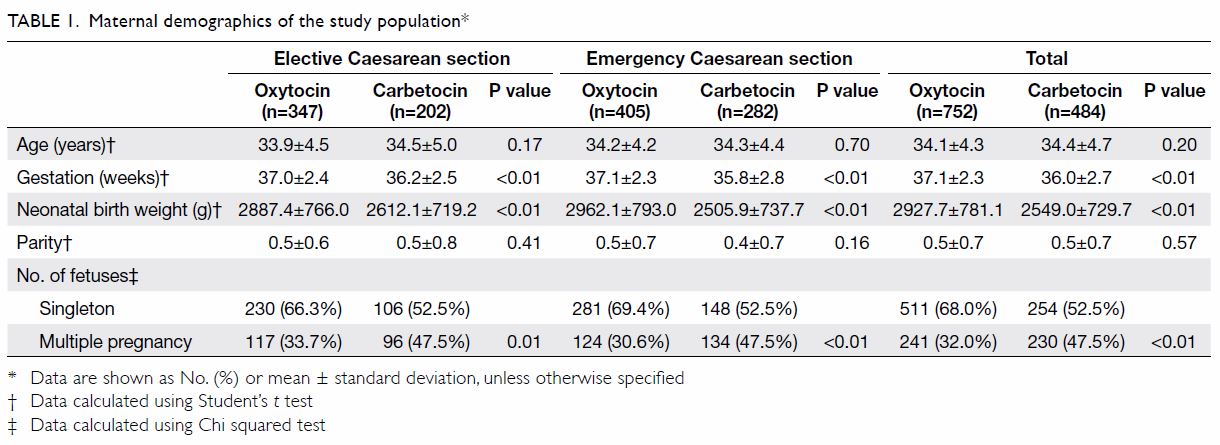

first. Compared with women who received oxytocin

first, women who received carbetocin first had earlier

gestation, lower neonatal birth weight, and a greater

proportion of twins or higher order pregnancy

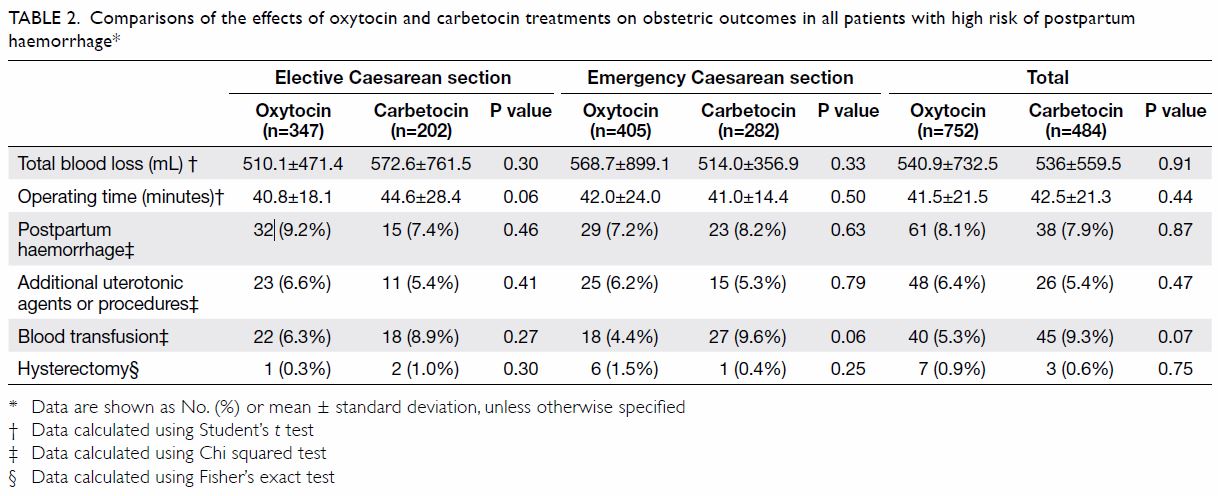

(Table 1). The two groups had comparable blood loss,

operating time, rate of postpartum haemorrhage,

requirement for additional uterotonics and

procedures, need for blood transfusion, and need for

hysterectomy (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparisons of the effects of oxytocin and carbetocin treatments on obstetric outcomes in all patients with high risk of postpartum haemorrhage

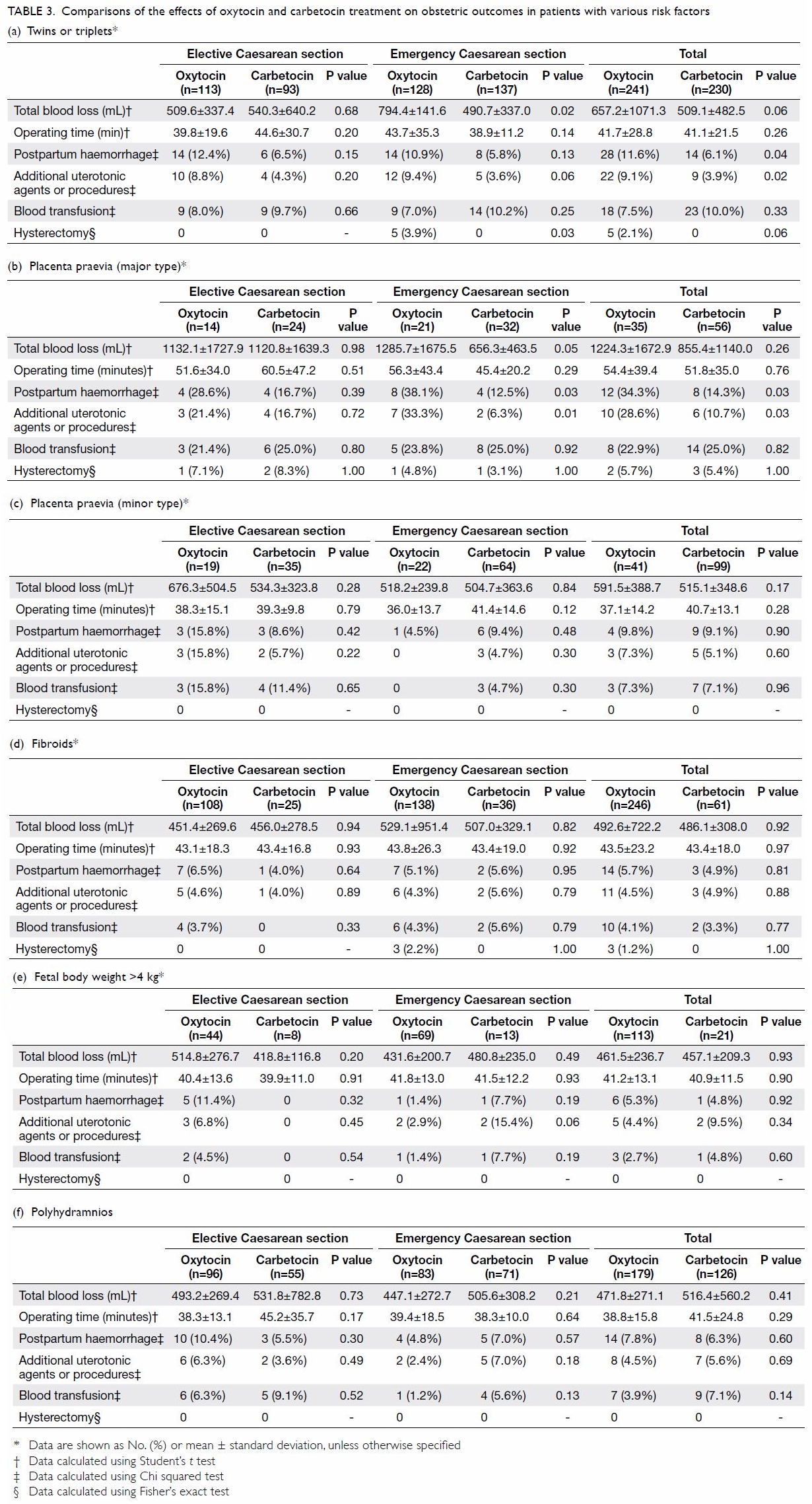

Significant reductions in the rate of postpartum

haemorrhage and in the requirement for additional

uterotonics or procedures were observed among

women with multiple pregnancies (Table 3a) and

women with major placenta praevia (Table 3b).

Significant reductions in total blood loss were also

observed for women with multiple pregnancies

and women with major placenta praevia in the

emergency Caesarean group. Additionally, the rate

of hysterectomy was significantly reduced in

women with multiple pregnancies in the emergency

Caesarean group.

Table 3. Comparisons of the effects of oxytocin and carbetocin treatment on obstetric outcomes in patients with various risk factors

For women with minor placenta praevia

(Table 3c), fibroids (Table 3d), macrosomia

(Table 3e), or polyhydramnios (Table 3f), no

significant differences in total blood loss, operating

time, rate of postpartum haemorrhage, requirement

for additional uterotonics, need for blood

transfusion, or need for hysterectomy were observed

between the two groups.

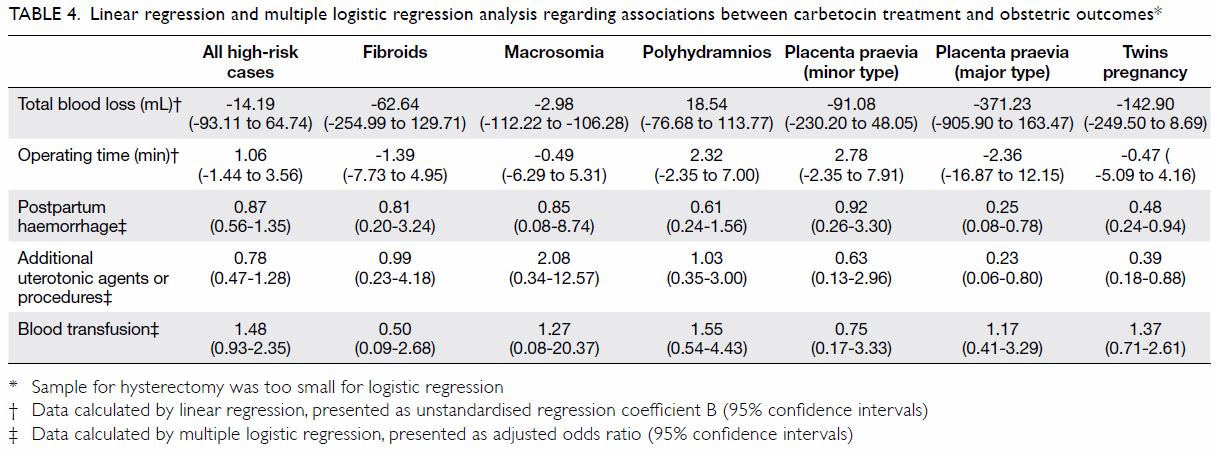

After adjustments for confounding effects,

linear regression analysis revealed reductions in

the rate of postpartum haemorrhage and in the

requirement for additional uterotonics or procedures

for Caesarean section in women with major placenta

praevia and in women with multiple pregnancies,

but not for other risk factors (Table 4).

Table 4. Linear regression and multiple logistic regression analysis regarding associations between carbetocin treatment and obstetric outcomes

No serious side-effects were reported after the

use of carbetocin.

Discussion

This study showed that the general cohort of women

with risk factors for postpartum haemorrhage who

received carbetocin treatment exhibited comparable

blood loss, rate of postpartum haemorrhage,

requirement for additional uterotonics or

procedures, need for blood transfusion, and need for

hysterectomy, compared with oxytocin treatment. Our results are inconsistent with the findings of

previous studies,11 12 13 14 in which there were reductions

in blood loss and risk of postpartum haemorrhage

among women in the general population following

receipt of carbetocin alone, compared with oxytocin

alone. We presume that the difference was related

partly to the use of different oxytocin regimens. In

particular, 40 IU oxytocin infusion (greater than the

effective dose of carbetocin, 10 IU oxytocin) was

used in the present study, whereas a smaller dose

of oxytocin infusion of 10 to 20 IU or a bolus of

5 IU was used in previous studies.4 15 16 Furthermore,

the indications for Caesarean section might

have differed between the present study and the

prior studies. Notably, carbetocin and oxytocin

have been shown to exert differential effects on

postpartum haemorrhage and related changes in

patients undergoing Caesarean section for different

indications.6

When we analysed individual risk factors for

postpartum haemorrhage, we found significant

reductions in the use of additional uterotonics

or procedures and in the rate of postpartum

haemorrhage in women with major placenta praevia

and in women with multiple pregnancies. We also

observed a significant reduction in total blood loss

in the emergency Caesarean section group for both

women with major placenta praevia and women with multiple pregnancies. Our results are consistent

with the findings of a previous study in which lower

haemoglobin and haematocrit differences were

found in women who received carbetocin treatment

during Caesarean section due to multiple gestation

or placenta praevia, compared with women who

received oxytocin treatment.15 Carbetocin can

induce strong contraction of an overdistended uterus

associated with twin pregnancies.16 However, a study in 2013 did not show beneficial effects of carbetocin

administration.17 The sample size was small in that

study and its design comprised a retrospective

before-and-after analysis. Additionally, we presume

that the beneficial effect of carbetocin in reduction

of bleeding in women with placenta praevia might

be related to its effectiveness in stimulating the

retroplacental myometrium.18 Carbetocin can

shorten the third stage, prevent and treat retained

placenta at term, and prevent and treat second

trimester abortion.19 However, our results were

inconsistent with the findings of a previous study,

in which the additional effects of carbetocin were

presumed to be trivial because of thinning in the

lower uterine myometrium, thereby reducing the

immunoreactivity of oxytocin receptors relative to

the upper part of the uterus.20

We noted that the significant differences in

outcomes between treatments were mainly due to the

contributions of the emergency Caesarean section

group. Previous studies have largely demonstrated

beneficial effects from carbetocin treatment in

women undergoing elective Caesarean section, but

not in women undergoing intrapartum Caesarean

section.15 21 A possible explanation might be that

emergency Caesarean sections were performed

before the date of scheduled Caesarean section date;

hence, the gestational age and fetal weight were

typically lower at the time of the operation.

The greatest strength of this study was that

it included a relatively large sample size, which

comprised 1236 patients in one hospital with

standard protocols. There were a few limitations in

this study. First, it used single-centre, retrospective

design. Second, complete blood count data were not

routinely collected before delivery during the study

period, so these data could not be compared among

subgroups. Third, the implementation of carbetocin

began in April 2017. Since this implementation, most

patients with the risk factors considered in this study

were administered carbetocin instead of oxytocin

infusion, in accordance with our department

protocol. This led to a comparison between different

time frames, during which there were changes in

medical personnel and training. Finally, judgement

regarding the use of additional uterotonic agents

and transfusion may have differed among attending

physicians.

In clinical practice, the use of carbetocin

has been acknowledged in guidelines from the

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of

Canada10 and the Royal College of Obstetricians

and Gynaecologists.9 We recommend the use of

carbetocin during Caesarean section for women with

multiple pregnancies and major placenta praevia,

based on the beneficial effects demonstrated in the

present study and in prior studies.15 In women with

other risk factors for postpartum haemorrhage, we recommend the use of oxytocin infusion, instead of

carbetocin.15 Larger studies or prospective trials are

needed to investigate the effectiveness of carbetocin

during Caesarean section for different indications

and in women with risk factors for postpartum

haemorrhage; such studies are also needed to

establish the cost-effectiveness of this relatively new

drug.

In conclusion, we found that carbetocin

and oxytocin infusion had differential effects on

the requirement for additional uterotonics or

procedures in women who underwent Caesarean

section for different indications. In particular,

compared with oxytocin infusion, carbetocin was

associated with a reduction in the requirement for

additional uterotonics or procedures for women

with multiple pregnancies and women with major

placenta praevia.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: KY Tse, FNY Yu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KY Tse, FNY Yu.

Drafting of the manuscript: KY Tse, KY Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KY Tse, KY Leung.

Acquisition of data: KY Tse, FNY Yu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KY Tse, FNY Yu.

Drafting of the manuscript: KY Tse, KY Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KY Tse, KY Leung.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KY Leung was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have no conflicts of

interests to disclose.

Funding/support

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agency in the public or commercial sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Hospital Authority Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Research Ethics Committee (Ref KC/KE-20-0073/ER-1).

References

1. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal

death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health

2014;2:e323-33. Crossref

2. Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of

postpartum haemorrhage. Am Fam Physician 2007;75:875-

82.

3. Su LL, Chong YS, Samuel M. Carbetocin for preventing

postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2012;(4):CD005457. Crossref

4. Fahmy NG, Yousef HM, Zaki HV. Comparative study

between effect of carbetocin and oxytocin on isofluraneinduced

uterine hypotonia in twin pregnancy patients

undergoing cesarean section. Egypt J Anaesth 2016;32:117-

21. Crossref

5. Hunter DJ, Schulz P, Wassenaar W. Effect of carbetocin,

a long-acting oxytocin analog on the postpartum uterus.

Clin Pharmacol Ther 1992;52:60-7. Crossref

6. Voon HY, Suharjono HN, Shafie AA, Bujang MA.

Carbetocin versus oxytocin for the prevention of

postpartum hemorrhage: a meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials in cesarean deliveries. Taiwan J Obstet

Gynecol 2018;57:332-9. Crossref

7. Kalafat E, Gokce A, O’Brien P, et al. Efficacy of carbetocin

in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic

review and Bayesian meta-analysis of randomized trials. J

Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019 Sep 19. Epub ahead of

print. Crossref

8. Onwochei DN, Van Ross J, Singh PM, Salter A, Monks DT.

Carbetocin reduces the need for additional uterotonics

in elective Caesarean delivery: a systematic review, meta-analysis

and trial sequential analysis of randomised

controlled trials. Int J Obstet Anesth 2019;40:14-23. Crossref

9. Mavrides E, Allard S, Chandraharan E, et al. Prevention

and management of postpartum haemorrhage. Green-top

Guideline No. 52. BJOG 2016;124:e106-49. Crossref

10. Leduc D, Senikas V, Lalonde AB. No. 235–Active

management of the third stage of labour: prevention and

treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol

Can 2018;40:e841-55. Crossref

11. El Behery MM, El Sayed GA, El Hameed AA, Soliman BS,

Abdelsalm WA, Bahaa A. Carbetocin versus oxytocin for

prevention of postpartum hemorrhage in obese nulliparous

women undergoing emergency cesarean delivery. J Matern

Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:1257-60. Crossref

12. Chen CY, Su YN, Lin TH, et al. Carbetocin in prevention of

postpartum hemorrhage: experience in a tertiary medical

center of Taiwan. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2016;55:804-9. Crossref

13. Mohamed Maged A, Ragab AS, Elnassery N, Ai Mostafa W,

Dahab S, Kotb A. Carbetocin versus syntometrine for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean

section. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;30:962-6. Crossref

14. Borruto F, Treisser A, Comparetto C. Utilization of

carbetocin for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage after

cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol

Obstet 2009;280:707-12. Crossref

15. Chen YT, Chen SF, Hsieh TT, Lo LM, Hung TH. A

comparison of the efficacy of carbetocin and oxytocin

on hemorrhage-related changes in women with cesarean

deliveries for different indications. Taiwan J Obstet

Gynecol 2018;57:677-82. Crossref

16. Seow KM, Chen KH, Wang PH, Lin YH, Kwang JL.

Carbetocin versus oxytocin for prevention of postpartum

hemorrhage in infertile women with twin pregnancy

undergoing elective cesarean delivery. Taiwan J Obstet

Gynecol 2017;56:273-5. Crossref

17. Demetz J, Clougueur E, D’Haveloose A, Staelen P, Ducloy AS,

Subtil D. Systematic use of carbetocin during cesarean

delivery of multiple pregnancies: a before-and-after study.

Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;287:875-80. Crossref

18. Abbas AM. Different routes and forms of uterotonics for

treatment of retained placenta: methodological issues. J

Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;30:2179-84. Crossref

19. Elfayomy AK. Carbetocin versus intra-umbilical oxytocin

in the management of retained placenta: a randomized

clinical study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:1207-13. Crossref

20. Kato S, Tanabe A, Kanki K, et al. Local injection of

vasopressin reduces the blood loss during cesarean section

in placenta previa. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2014;40:1249-56. Crossref

21. Elbohoty AE, Mohammed WE, Sweed M, Bahaa Eldin AM,

Nabhan A, Abd-El-Maeboud KH. Randomized controlled

trial comparing carbetocin, misoprostol, and oxytocin

for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage following

an elective cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet

2016;34:324-8. Crossref