Parapharyngeal abscess presenting as masticatory otorrhoea-persistent foramen tympanicum as a route of drainage: a case report

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Parapharyngeal abscess presenting as masticatory

otorrhoea-persistent foramen tympanicum as a route of drainage: a case

report

KH Lee, FRCR, FHKCR; YL Li, MB, BS, FRCR; ML Yu,

MB, ChB, FRCR

Department of Radiology, Queen Mary Hospital,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KH Lee (viclkh88@gmail.com)

Case report

A 26-year-old woman presented to the emergency

department of Queen Mary Hospital in August 2014 with fever and right

otorrhea following extraction of her right lower third molar 5 days

previously. Physical examination revealed right buccal swelling, limited

mouth opening, and pus-like discharge in the right external auditory canal

(EAC) exacerbated by mastication. There was no hearing loss or facial

nerve palsy. Otoscopy revealed granulation tissue and pus arising from the

anterior wall of the inner right EAC.

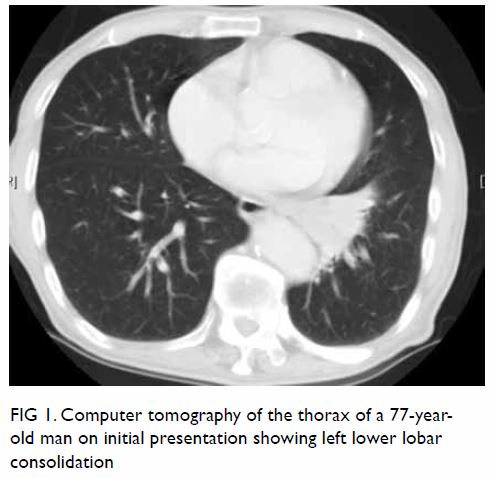

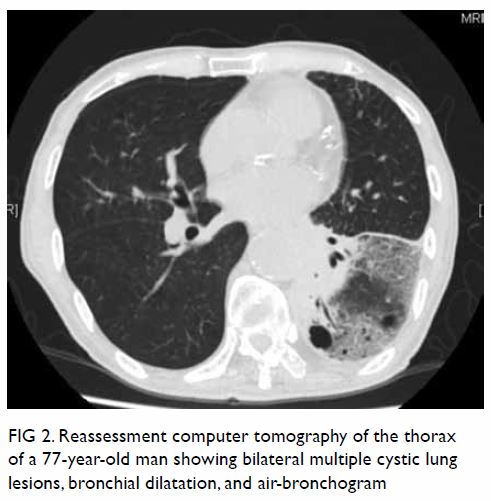

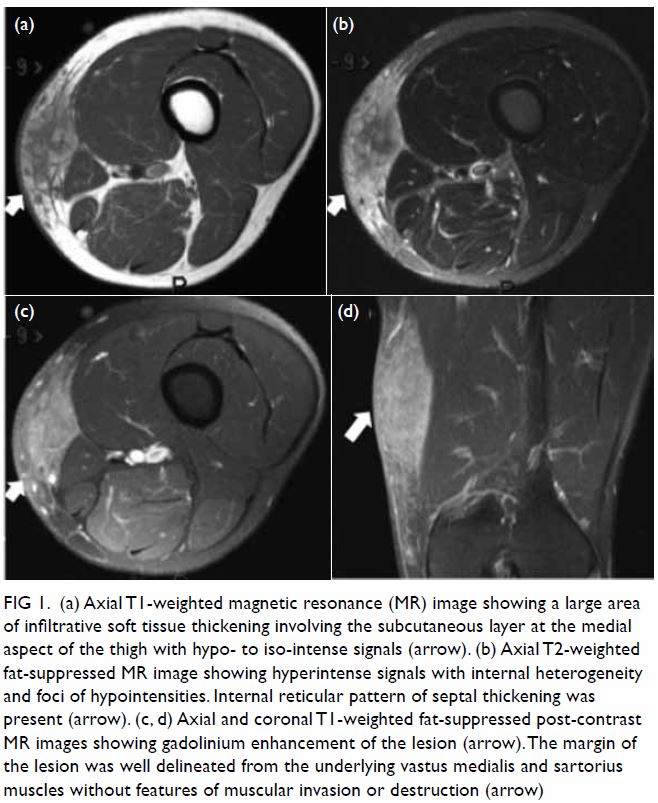

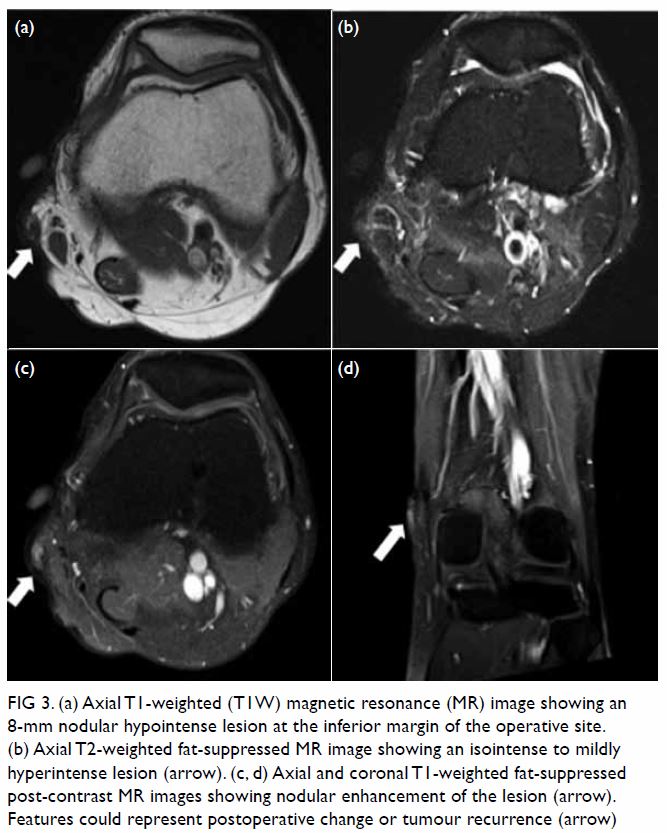

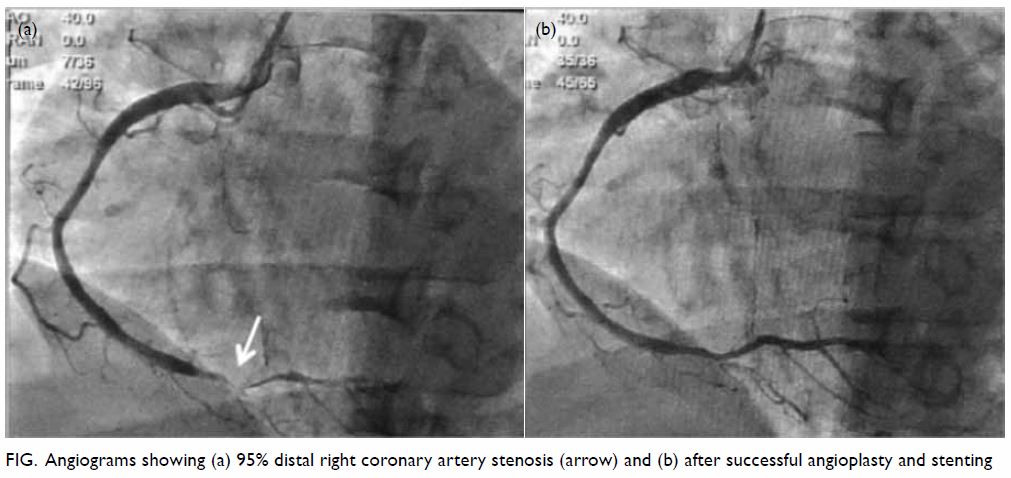

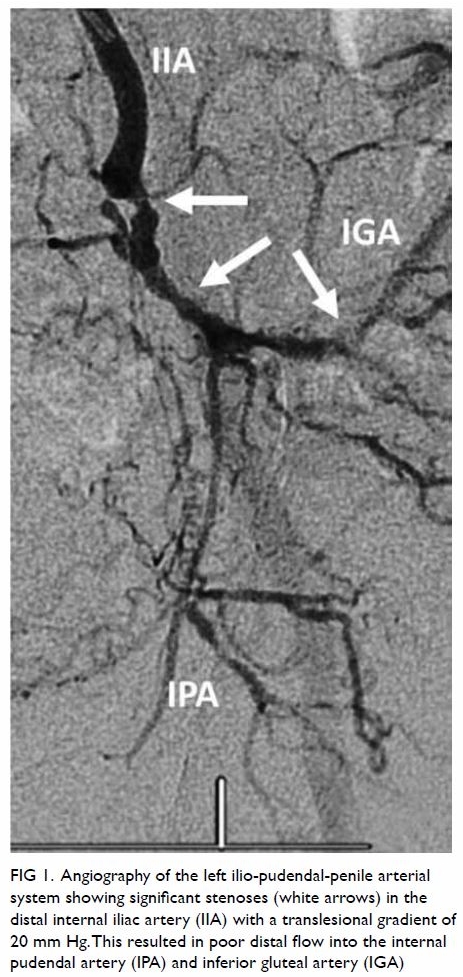

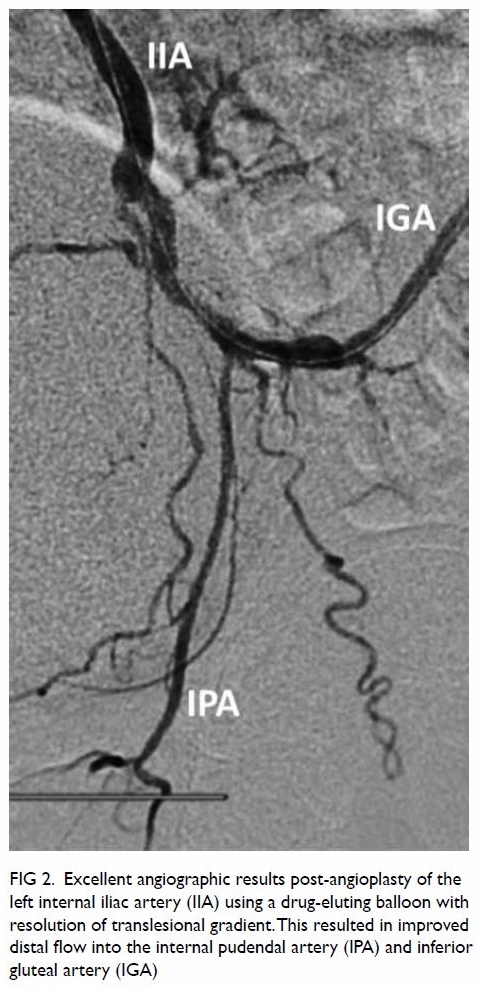

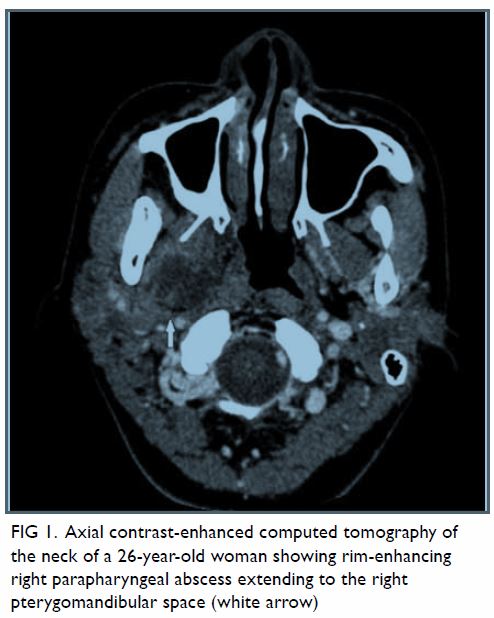

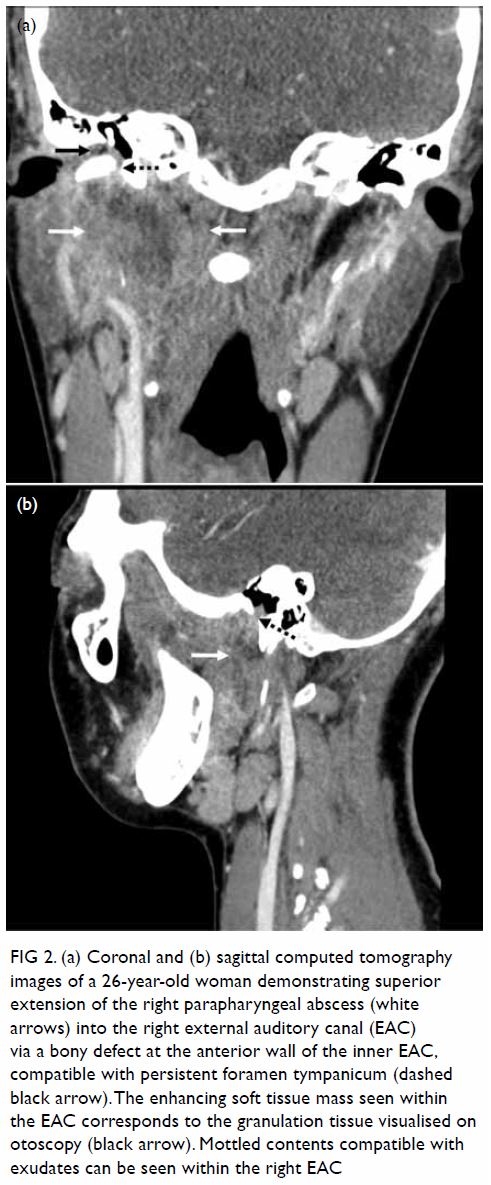

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showed a

right parapharyngeal rim enhancing collection (Fig 1) tracking into the right

temporomandibular fossa. Enhancing soft tissue was seen at the

inner one-third of the right EAC. A bony defect was present at its

anterior wall, compatible with a persistent foramen tympanicum (also known

as foramen of Huschke), allowing communication between the EAC and the

temporomandibular fossa (Fig 2). Overall findings were compatible with right

parapharyngeal abscess discharging via a persistent foramen tympanicum

into the right EAC.

Figure 1. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the neck of a 26-year-old woman showing rim-enhancing right parapharyngeal abscess extending to the right pterygomandibular space (white arrow)

Figure 2. (a) Coronal and (b) sagittal computed tomography images of a 26-year-old woman demonstrating superior extension of the right parapharyngeal abscess (white arrows) into the right external auditory canal (EAC) via a bony defect at the anterior wall of the inner EAC, compatible with persistent foramen tympanicum (dashed black arrow). The enhancing soft tissue mass seen within the EAC corresponds to the granulation tissue visualised on otoscopy (black arrow). Mottled contents compatible with exudates can be seen within the right EAC

The patient was treated with a course of

antibiotics in view of her stable condition and lack of airway compromise.

The patient responded clinically and repeat computed tomography scan 1

week after initial presentation showed complete resolution of the right

parapharyngeal abscess and enhancing soft tissue within the right EAC.

Subsequent bacterial culture of the right ear discharge yielded Streptococcus

anginosus, a common cause of oral infection.

Discussion

Parapharyngeal abscesses are deep cervical

infections with potential serious complications such as shock,

mediastinitis, jugular vein thrombosis, upper airway obstruction, and

death. Tonsillitis and odontogenic infection are the most common

aetiologies. The clinical presentation typically involves fever, neck

pain, odynophagia, neck oedema, and upper airway obstruction.1

Otorrhea is typically caused by external or middle

ear pathologies such as otitis. Otorrhoea as a presenting symptom for a

neck abscess is highly unusual. In our literature review, only two cases

were found. Biron et al2 described

a patient with a submandibular abscess that tracked into the ipsilateral

external auditory meatus via the parapharyngeal and masticator spaces.

Pepato et al3 reported a case of

lower third molar infection presenting as purulent ear discharge, with

persistent foramen tympanicum found in a follow-up cone-beam computed

tomography study. The route of spread was postulated to be either via the

Santorini fissures (the tiny defects in the anterior wall of the

cartilaginous EAC) or via a persistent foramen tympanicum.

Persistent foramen tympanicum, first described by

Emil Huschke in 1844, represents a failure of ossification of the tympanic

part of the temporal bone and normally occurs from birth with completion

by age 5 years. The foramen is located at the anteroinferior aspect of the

EAC, just posterior to the temporomandibular joint. Incidence is quoted

from 4.6% to 22.7% based on radiological and cadaveric studies.4

The majority of individuals with the foramen are

asymptomatic although various complications have been reported. Most are

benign, such as salivation from the ear during mastication and spontaneous

herniation of the temporomandibular joint into the EAC leading to otalgia

and tinnitus. Iatrogenic middle ear injury is possible when the foramen is

inadvertently traversed during temporomandibular joint arthroscopy.5 It is possible that the lack of bony integrity reduces

mechanical resistance to pathological processes, such as the spreading of

parapharyngeal abscess in our case. Parotid pleomorphic adenomas have also

been reported to herniate through the foramen to present as an EAC mass.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

case to provide direct radiological evidence of persistent foramen

tympanicum as a route for drainage leading to masticatory otorrhoea. It is

important for doctors to be aware of the clinical presentation to permit

diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept, image

acquisition, image and data interpretation, manuscript drafting, and

critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors had full

access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Patient consent was obtained for the purpose of

this case study.

References

1. Brito TP, Hazboun IM, Fernandes FL, et

al. Deep neck abscesses: study of 101 cases. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol

2017;83:341-8. Crossref

2. Biron A, Halperin D, Sichel JY, Eliashar

R. Deep neck abscess of dental origin draining through the external ear

canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;133:166-7. Crossref

3. Pepato AO, Yamaji MA, Sverzut CE,

Trivellato AE. Lower third molar infection with purulent discharge through

the external auditory meatus. Case report and review of literature. Int J

Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;41:380-3. Crossref

4. Akbulut N, Kursun S, Aksoy S, Kurt H,

Orhan K. Evaluation of foramen tympanicum using cone-beam computed

tomography in orthodontic malocclusions. J Craniofac Surg 2014;25:e105-9.

Crossref

5. Nakasato T, Nakayama T, Kikuchi K et al.

Spontaneous temporomandibular joint herniation into the external auditory

canal through a persistent foramen tympanicum (Huschke): radiographic

features. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2013;37:111-3. Crossref