DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154629

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

Heat treatment of biochemical samples to inactivate Ebola virus: does it work in practice?

Timothy B Nguyen, MD;

Vanessa Clifford, MB, BS;

Azni Abdul Wahab, MB, BS;

Vincent Sinickas, FRCPA, FRACP

Department of Pathology, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia

Full

paper in PDF

Full

paper in PDF

To the Editor—We read with interest the article

by Chong et al

1 on the effects of plasma heating

procedures on common biochemical tests. Heat

treatment at 60°C for 60 minutes has also been

suggested by our Australian guidelines as a means

to inactivate Ebola virus prior to routine laboratory

processing.

2

We recently performed a similar study to

Chong et al

1 in our laboratory at the Royal Melbourne

Hospital (Parkville, Australia). De-identified plasma

(n=29) and serum (n=38) venous samples were

collected in plastic BD vacutainer tubes (Becton,

Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes [NJ], US)

for electrolyte, liver function, and troponin testing on

the Architect c16000 analyser (Abbott Laboratories,

North Chicago [IL], US). After centrifugation, two

0.5-mL aliquots were obtained, one placed in a

heat block at 60°C for 60 minutes, and the other

paired sample left at room temperature. After heat

inactivation, 24/27 (89%) plasma samples and 25/36

(69%) serum samples changed to a viscous jelly-like

substance (

Fig) and caused aspiration error on the

Architect analyser. Centrifugation, manual stirring,

and vortexing did not resolve the problem.

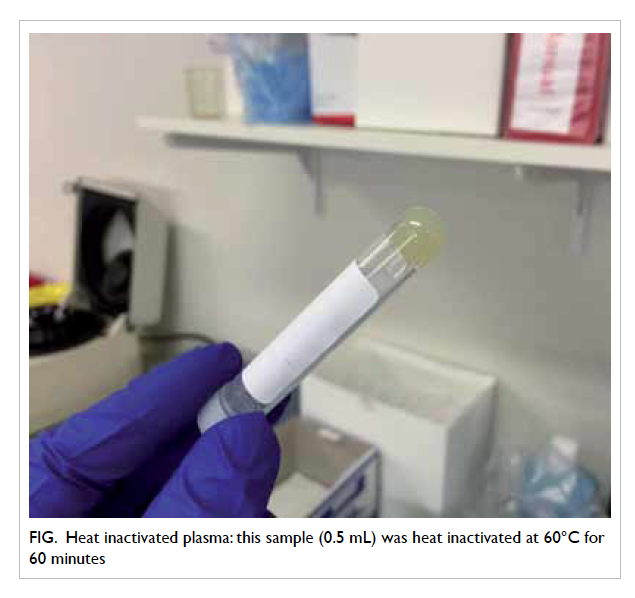

Figure.

Figure. Heat inactivated plasma: this sample (0.5 mL) was heat inactivated at 60°C for 60 minutes

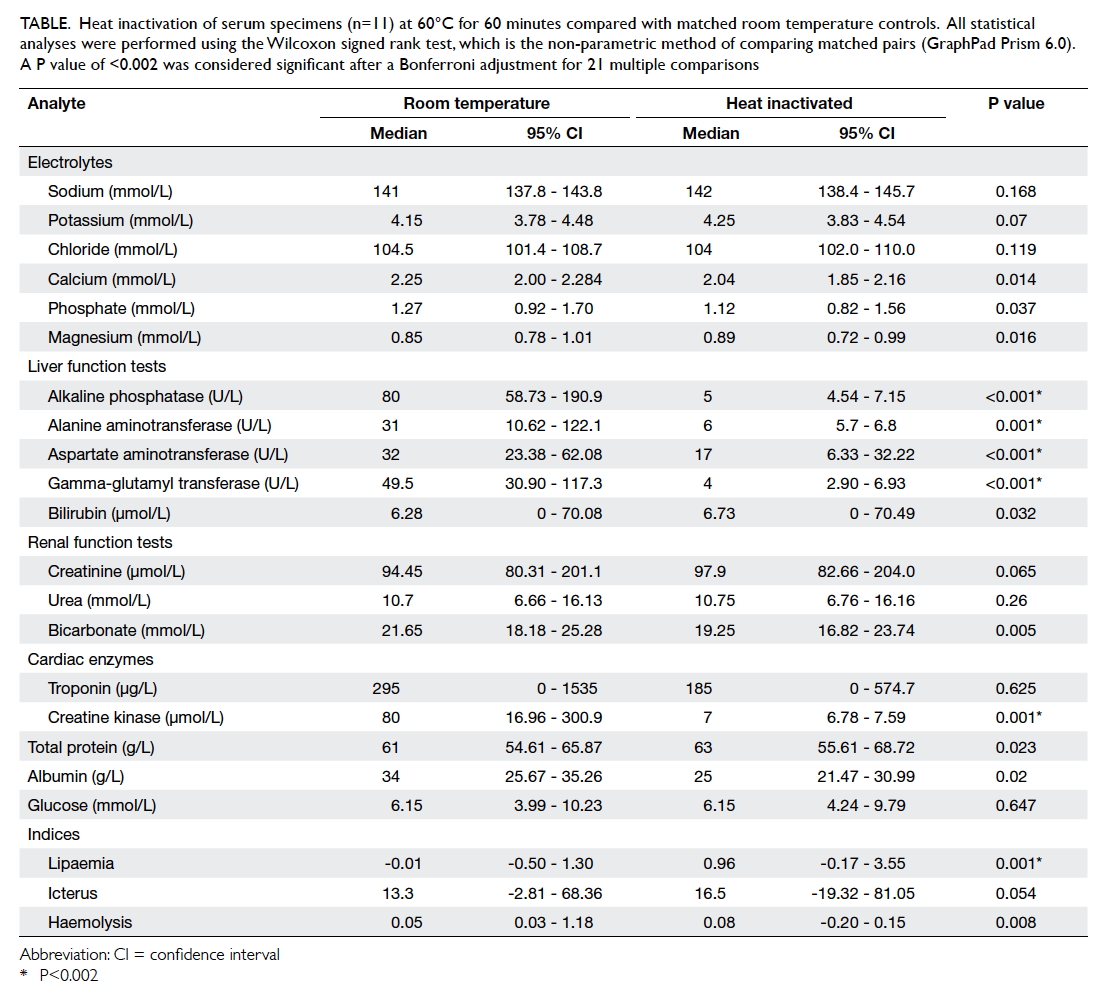

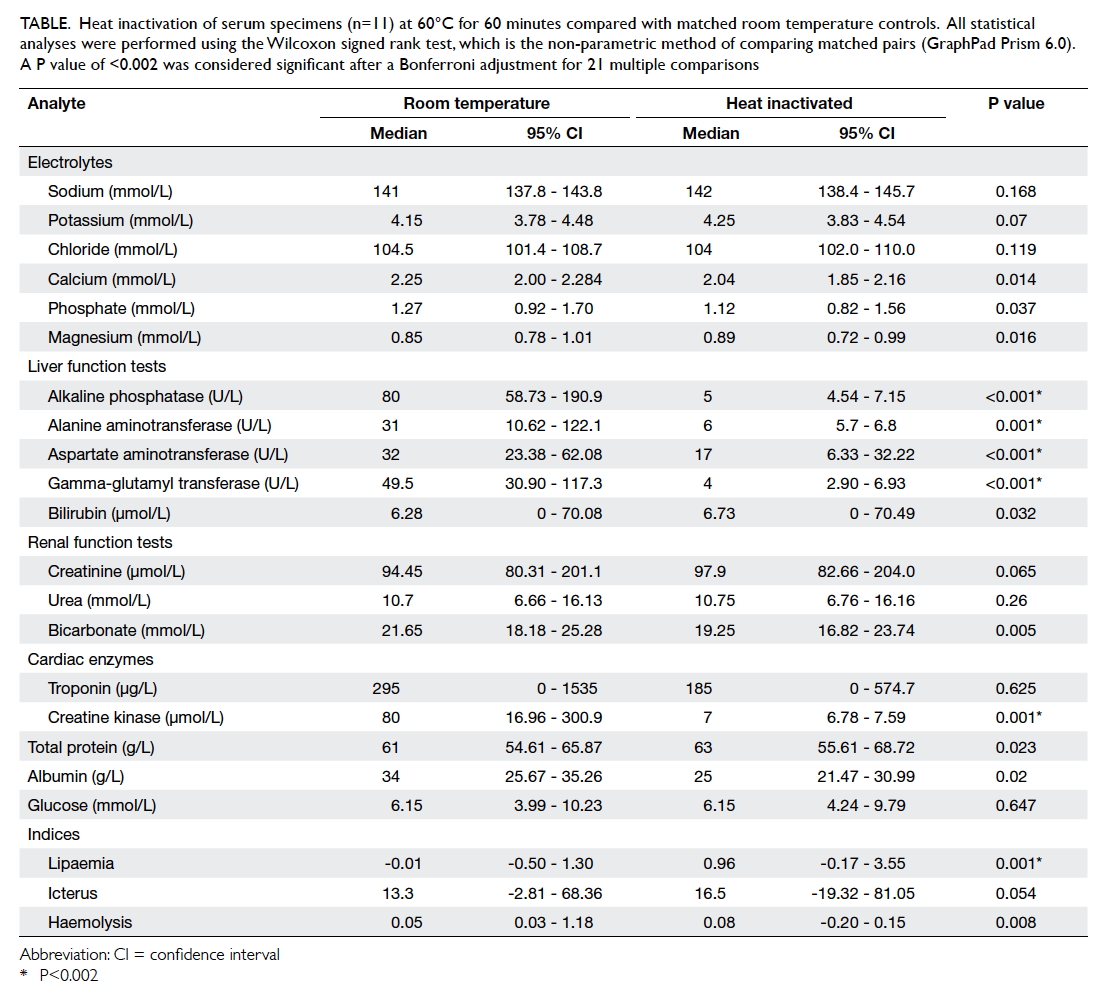

In serum samples that were not denatured

by heating, electrolyte measurements had a strong

correlation with results obtained by standard

testing. Nonetheless, enzyme tests (liver function

and troponin) showed a poor correlation (

Table).

Interestingly, these problems have not been

previously reported.

2 3 The use of a heat block instead of a water bath

2 may have exposed our specimens to

unequal heating, hotspots, or spikes in temperature,

causing condensation or irreversible denaturing of

proteins.

4

Table.

Table. Heat inactivation of serum specimens (n=11) at 60°C for 60 minutes compared with matched room temperature controls. All statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test, which is the non-parametric method of comparing matched pairs (GraphPad Prism 6.0). A P value of <0.002 was considered significant after a Bonferroni adjustment for 21 multiple comparisons

We found that, in our hands, it was not

possible to provide biochemical testing after heat

treatment, as recommended by current national and

international guidelines.

References

1. Chong YK, Ng WY, Chen SP, Mak CM. Effects of a plasma

heating procedure for inactivating Ebola virus on common

chemical pathology tests. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:201-7.

Crossref

2. Public Health Laboratory Network. Laboratory procedures

and precautions for samples collected from patients

with suspected viral haemorrhagic fevers: Australian

Government Department of Health; 2014. Available from:

http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-pubs-other-vhf.htm. Accessed 10 May 2015.

3. Bhagat CI, Lewer M, Prins A, Beilby JP. Effects of heating

plasma at 56 degrees C for 30 min and at 60 degrees C

for 60 min on routine biochemistry analytes. Ann Clin

Biochem 2000;37:802-4.

Crossref

4. Wetzel R, Becker M, Behlke J, et al. Temperature behaviour

of human serum albumin. Eur J Biochem 1980;104:469-78.

Crossref

Author’s reply

YK Chong, MB, BS;

WY Ng, MB, ChB, PhD;

Sammy PL Chen, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology);

CM Mak, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)

Chemical Pathology Laboratory, Department of Pathology, Princess

Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

To the Editor—We would like to thank Nguyen et al

for their comments.

We concur with Nguyen et al that the use of

heat blocks rather than a water bath may result in

unequal heating, hotspots, or spikes in temperature.

In our previous experience with heating procedures

performed to determine alkaline phosphatase

isoenzymes,

1 exposure of plasma to a temperature

of 65°C caused gelling of most plasma specimens

(unpublished observations). We suspect that the

gelling temperature of normal human plasma is 60°C

to 65°C.

In our experiments, we use a W14 water bath

with 14 L capacity (Sheldon Manufacturing Inc,

Cornelius [OR], US). The water bath has a much

higher heat capacity than heat blocks, due to the large

volume of water, as well as the considerably higher

specific heat capacity of water (4.1813 J g

-1 K

-1) when

compared with aluminium (0.897 J g

-1 K

-1),

2 a metal

often used to manufacture heat blocks.

References

1. Panteghini M, Bais R. Serum enzymes. In: Burtis CA,

Ashwood ER, Bruns DE. Tietz textbook of clinical

chemistry and molecular diagnostics. St Louis, US:

Elsevier; 2012: 579.

Crossref2. Chung DD. Composite materials. London: Springer; 2010: 283.

Crossref