DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164987

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Feasibility of short double-balloon

enteroscopy-assisted endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography in patients with

surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy:

experience in a regional centre

SW Cheung, MRCP, FHKCP1; KS Cheng, MRCP, FHKCP1; WM Yip, MRCP, FHKCP2; KK Li, MBBS, FRCP1

1 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Pok Oi Hospital, Yuen Long, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr SW Cheung (saiwahc@hotmail.com)

A video clip showing double-balloon enteroscopy–assisted endoscopic

retrograde cholangiopancreatography is available at www.hkmj.org

A video clip showing double-balloon enteroscopy–assisted endoscopic

retrograde cholangiopancreatography is available at www.hkmj.orgCase Reports

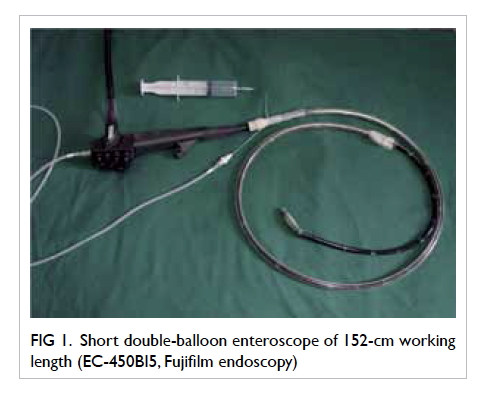

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

(ERCP) is a standard endoscopic technique for

treating biliary obstruction and cholangitis. The

presence of surgically altered gastrointestinal

anatomy, however, poses a major technical difficulty

to the procedure due to the long and tortuous access

to the small bowel. We report a three-case series

with successful attempts at short double-balloon

enteroscopy (DBE)–assisted ERCP in patients

with postoperative gastrointestinal anatomy. The

enteroscope employed was EC-450BI5, Fujifilm

endoscopy (Fig 1) and the sedation agents used

in all procedures were dexmedetomidine and

fentanyl continuous infusion combined with bolus

midazolam.

Case 1

A 76-year-old man was admitted to our hospital in

December 2015 with acute cholangitis that presented

as fever and deranged liver function tests (LFT)

with predominant elevation of alkaline phosphatase

(ALP). He had a history of stroke, hyperlipidaemia,

and a Billroth II gastrectomy performed 30

years ago. Blood cultures grew Escherichia coli.

Ultrasonography of the hepatobiliary system

revealed a 5-mm stone in the common bile duct

(CBD).

The first ERCP using a standard side-view

duodenoscope and end-view gastroscope failed

to identify the papilla. He continued to receive

antibiotic treatment, with the fever reduced but

liver biochemistry remained elevated. The DBE-assisted

ERCP was performed 2 weeks later with an

enteroscope of 152-cm working length. The papilla

was reached over the afferent limb of the small bowel

by manipulation of the overtube only (no balloon

inflation), followed by successful cannulation of

the CBD. Cholangiogram revealed a 1.2-cm dilated

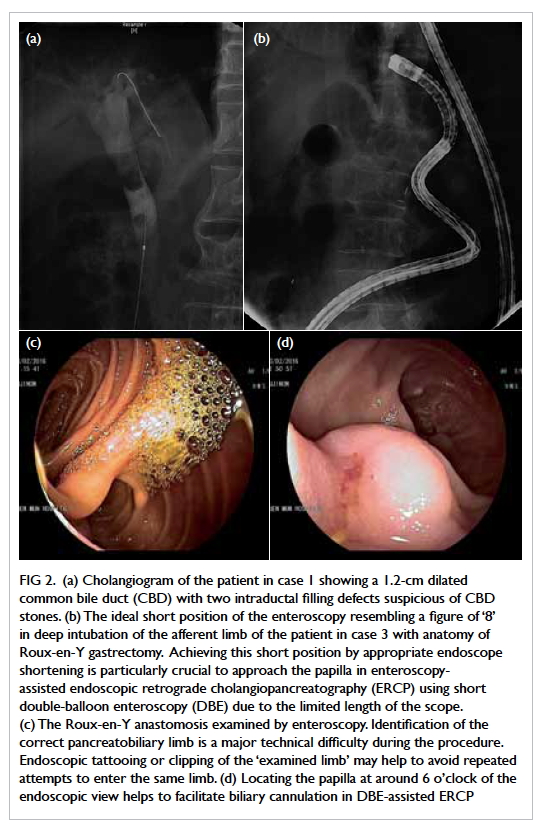

CBD with two intraductal filling defects (Fig 2a).

Pre-cut papillotomy on-stent was performed with

pre-insertion of a 7-French 7-cm plastic biliary stent.

The plastic stent was removed after papillotomy

and the papilla was dilated using a controlled radial

expansion (CRE) balloon dilator of 12-mm size and

subsequently stones were removed by a basket. The

ERCP procedure was completed in 115 minutes and

there were no complications. The patient’s LFT had

normalised at a follow-up 3 weeks later.

Figure 2. (a) Cholangiogram of the patient in case 1 showing a 1.2-cm dilated common bile duct (CBD) with two intraductal filling defects suspicious of CBD stones. (b) The ideal short position of the enteroscopy resembling a figure of ‘8’ in deep intubation of the afferent limb of the patient in case 3 with anatomy of Roux-en-Y gastrectomy. Achieving this short position by appropriate endoscope shortening is particularly crucial to approach the papilla in enteroscopy-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) using short double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) due to the limited length of the scope. (c) The Roux-en-Y anastomosis examined by enteroscopy. Identification of the correct pancreatobiliary limb is a major technical difficulty during the procedure. Endoscopic tattooing or clipping of the ‘examined limb’ may help to avoid repeated attempts to enter the same limb. (d) Locating the papilla at around 6 o’clock of the endoscopic view helps to facilitate biliary cannulation in DBE-assisted ERCP

Case 2

An 80-year-old man presented in January 2016

with a history of hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis,

and cerebral infarct. A Billroth II gastrectomy

had been performed 10 years previously for

gastrointestinal bleeding. He had an episode of acute

cholangitis 4 months ago. Endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography using a standard end-view

gastroscope failed to reach the papilla and the

infection resolved after a course of antibiotic. Follow-up

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography 3

weeks earlier had revealed a 1.2-cm distal CBD stone

with the CBD dilated to 1.7 cm. He then attended the

hospital again for fever, E coli septicaemia, and an

obstructive pattern of liver derangement; bilirubin

level was 93 µmol/L and ALP level was 1224 U/L.

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was

established and antibiotics were continued until

DBE-assisted ERCP was performed 2 weeks later.

With the push-pull manoeuvre, the blind end of

the afferent loop was reached. Initially, a nearby

minor papilla was mistaken as the major papilla and

repeated attempts failed to cannulate it.

The true major papilla was then identified

5 cm proximal to the minor papilla and pre-cut

papillotomy was performed due to difficult

cannulation. The impacted CBD stone was removed

following papillotomy and balloon sphincteroplasty

was performed with a 12-mm CRE balloon.

Subsequent cholangiogram was clear with a 1.5-cm

dilated CBD. The operating time was 163 minutes.

The patient remained asymptomatic and LFT had

normalised at a follow-up 1 month later.

Case 3

A female patient aged 81 years with a history

of mild Parkinson’s disease had undergone

gastrectomy 30 years ago for peptic ulcer disease.

She presented to our hospital in February 2016 for

biliary pancreatitis with sudden onset of jaundice

associated with epigastric pain. Amylase level was

elevated to 698 U/L, bilirubin level to 35 µmol/L,

and an ALP level of 1001 U/L. Ultrasonography of

the hepatobiliary system detected grossly dilated

intrahepatic ducts (IHD) and the CBD measured

up to 2.4 cm in diameter with one obstructing

CBD stone measuring 1.5 cm. The first gastroscopy

confirmed a previous total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Percutaneous transhepatic

biliary drainage was attempted but failed due to the

resolution of the IHD dilatation. The patient was

then managed conservatively with antibiotics and

a DBE-assisted enteroscopy was scheduled 3 weeks

later. The 152-cm DBE identified the blind end of

the afferent limb while the endoscope advanced to

140 cm from the incisors after push-pull manoeuvre

(Fig 2b to d). Successful guidewire cannulation was

followed with a cholangiogram that showed a dilated

CBD with no filling defect. In view of the recent

history of biliary obstruction and the possibility of

a passed stone, the papilla was dilated to 13.5 mm

with the CRE balloon and good bile drainage was

observed. The operating time was 130 minutes. The

major difficulty encountered was that the tip of the

enteroscope was very unstable making it difficult

to maintain the distal blind end and it was easily

slipped out proximally. As such, repeated endoscope

manipulation was required to achieve optimal

positioning. Postoperatively, the patient was well,

bilirubin normalised, and ALP level had reduced to

266 U/L at 1-month follow-up.

Discussion

Balloon enteroscopy–assisted ERCP using either

single-balloon enteroscopy or DBE has been

reported to be an effective modality for ERCP in these

patients.1 2 3 Traditional DBE with 200-cm length and

narrow (2.2-mm) accessory working channel limits

the utilisation of conventional ERCP accessories.

Recent attempts with a short 152-cm DBE have

been highly successful.1 2 4 To date, there have been

approximately 200 reports of patients who have

undergone ERCP using this short DBE procedure.

The success rate for reaching the blind end of the

afferent limb was 86% to 100%; it is not inferior to

that achieved using a long-type balloon enteroscope.4

The short-type enteroscope accommodates the use

of most available accessories to perform ERCP-related

procedures such as sphincterotomy, balloon

dilatation, stone extraction, and deployment of

plastic or metallic stents.

In our small series, all patients ran an

uneventful course during the perioperative and

postoperative period and none had any apparent

complications. The overall procedural complication

rate has been reported to be 8% to 10%, with the rate

of major complications of perforation or emphysema

being around 3.5%.4 The risk of complications,

however, may vary according to different surgical

approaches with consequent significant differences

in the endoscopic techniques anticipated.3 4 5 Since

it is a relatively new and evolving endoscopic

technique, these rates are still experience-dependent

and patients should be closely observed after the

procedure.

The ERCP in the patient with Roux-en-Y reconstruction posed particular technical

difficulties. The endoscopist should review previous

surgical reports in detail to map and anticipate

the endoscopic view at the anastomotic site. On

reaching the Roux-en-Y anastomosis, identification

of the pancreatobiliary limb is often difficult. After

choosing either limb, the endoscopist could perform

endoscopic marking by a clip or Indian ink tattoo at

the entrance of the chosen limb (Fig 2c). If the chosen

limb is confirmed wrong under fluoroscopy, the

endoscopist can return the endoscope to the Roux-en-Y anastomosis and then insert the endoscope into

the other limb. A marking at the entrance of a limb

has been shown to be useful as it avoids repeated

misidentification of the limb to be entered.6

Barotrauma is the major cause of intestinal

perforations and may be a result of excessive air

insufflation forming a closed loop between the

blind end and the inflated overtube or enteroscope

balloon.7 Use of carbon dioxide insufflation instead

of air insufflation may reduce the chance of this

closed-loop phenomenon. Additionally, use of a

transparent hood at the tip of the enteroscope with

instillation of water into the intestinal lumen has

also been suggested to maintain the endoscopic

view without gas insufflation and avoid consequent

barotrauma.8

With regard to the cannulation techniques,

the catheter exits from a 7 o’clock direction of

the enteroscope during DBE-assisted ERCP.

Endoscopists should attempt to locate the papilla

at 6 o’clock of the endoscopic view to facilitate

biliary cannulation (Fig 2b). In case of an unstable

endoscopic manoeuvre, an inflated enteroscope

balloon may help to grip the intestine and stabilise

the manipulation. In cases where the papilla is

located at 11 to 12 o’clock in the endoscopic view,

the overtube balloon should remain inflated and the

enteroscope rotated to solve difficult cannulation.6

In conclusion, short DBE-assisted ERCP is

a safe and effective endoscopic method to treat

patients with surgically altered anatomy and

biliary conditions. Nonetheless local experience in

enteroscopy-assisted ERCP, particularly using the

short DBE, is scant because of the unavailability

of the endoscopic devices. Further discussion and

training opportunities are encouraged to consolidate

experience and minimise procedural complications

in future practice.

References

1. Moreels TG. Altered anatomy: enteroscopy and ERCP

procedure. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2012;26:347-57. Crossref

2. Cheng CL, Liu NJ, Tang JH, et al. Double-balloon

enteroscopy for ERCP in patients with Billroth II anatomy:

results of a large series of papillary large-balloon dilation

for biliary stone removal. Endosc Int Open 2015;3:E216-22. Crossref

3. Mönkemüller K, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P.

Therapeutic ERCP with the double-balloon enteroscope in

patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Gastrointest Endosc

2008;67:992-6. Crossref

4. Kato H, Tsutsumi K, Harada R, Okada H, Yamamoto K.

Short double-balloon enteroscopy is feasible and effective

for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in

patients with surgically altered gastrointestinal anatomy.

Dig Endosc 2014;26 Suppl 2:130-5. Crossref

5. Katanuma A, Yane K, Osanai M, Maguchi H. Endoscopic

retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients

with surgically altered anatomy using balloon-assisted

enteroscope. Clin J Gastroenterol 2014;7:283-9. Crossref

6. Hatanaka H, Yano T, Tamada K. Tips and tricks of double-balloon

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

(with video). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2015;22:E28-34. Crossref

7. De Koning M, Moreels TG. Comparison of double-balloon

and single-balloon enteroscope for therapeutic endoscopic

retrograde cholangiography after Roux-en-Y small bowel

surgery. BMC Gastroenterol 2016;16:98. Crossref

8. Yamamoto H. Be aware of the fatal risk of air embolism.

Dig Endosc 2014;26:23. Crossref