DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144237

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Unexplained childhood anaemia: idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis

KK Siu, MB, ChB, MRCPCH1; Rever Li, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2; SY Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2

1 Department of Paediatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

2 Department of Paediatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KK Siu (skk053@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

This report demonstrates pulmonary haemorrhage

as a differential cause of anaemia. Idiopathic

pulmonary hemosiderosis is a rare disease in children;

it is classically described as a triad of haemoptysis,

pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph, and iron-deficiency

anaemia. However, anaemia may be the

only presenting feature of idiopathic pulmonary

hemosiderosis in children due to occult pulmonary

haemorrhage. In addition, the serum ferritin is falsely

high in idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis which

increases the diagnostic difficulty. We recommend

that pulmonary haemorrhage be suspected in any

child presenting with iron-deficiency anaemia and

persistent bilateral pulmonary infiltrates.

Case report

We report the case of a 5-year-old boy, who

presented with recurrent episodes of unexplained

iron-deficiency anaemia in February 2010 since the

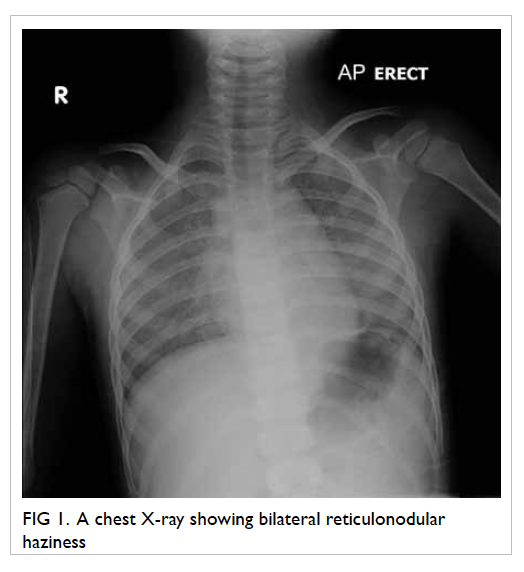

age of 27 months. Serial chest X-rays (CXRs) showed

bilateral reticulonodular haziness. Bronchoalveolar

lavage and lung biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of

idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (IPH).

The patient first presented at 27 months of age

in Mainland China with malaise, loss of appetite,

and shortness of breath for 10 days. He did not have

fever, cough, or haemoptysis. He received two doses

of H1N1 vaccination before pallor was noted. There

was no history of drug or herb intake.

The presenting haemoglobin (Hb) level was

65 g/L (reference range [RR], 115-145 g/L), mean

corpuscular volume (MCV) 84.4 fL (RR, 76-90 fL),

mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) level 25.8 pg (RR,

25-31 pg), and reticulocyte count 10.4% (reference

level [RL], <2%). White cell count and platelet count

were unremarkable. Blood smear showed moderate

anisopoikilocytosis with polychromasia. Bone

marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy revealed

active marrow with erythroid preponderance.

Other investigations were performed for

anaemia. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was

elevated to 980 U/L (RL, <615 U/L). Haptoglobin level

was reduced (<0.09 g/L; RR, 0.3-2.7 g/L). Direct

Coombs test was negative. Bilirubin was normal.

Urine for bilirubin and urobilinogen was negative.

Haemoglobin pattern, serum vitamin B12, and G6PD

activity were unremarkable. Serum ferritin level

was 137 pmol/L (RR, 45-449 pmol/L). Antinuclear

antibody assay was negative. Flow cytometry

showed normal expression of CD55 and CD59 which

ruled out paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria.

Donath-Landsteiner antibody assay was negative,

which excluded the diagnosis of paroxysmal cold

haemoglobinuria.

Blood work for viral infection including

antibodies to parvovirus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV),

mycoplasma, and viral titres was unremarkable.

Screening for blood loss was negative. Stool

for occult blood and urine for Hb were negative. Red

blood cell scan showed no evidence of haemorrhage.

Blood transfusion was given to correct the

anaemia. Microcytic hypochromic anaemia was

noted at 2 months after presentation. Haemoglobin

level was 54 g/L. Mean corpuscular volume

dropped from 84.4 fL to 68 fL. Mean corpuscular

haemoglobin level was 21.3 pg. Iron profile showed a low

serum iron level of 3 µmol/L (RR, 5-20 µmol/L), elevated

total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 70 µmol/L

(RR, 37-68 µmol/L), and iron saturation of 4% (RR,

20-55%). However, the serum ferritin level was normal at

220 pmol/L (RR, 45-449 pmol/L). Iron supplement

was started as a therapeutic trial for suspected iron-deficiency

anaemia.

His Hb level remained stable in the next 2 years.

However, in the subsequent 8 months, there were

three intermittent episodes of anaemia (lowest Hb level,

60 g/L). The anaemia occurred with fever and cough

which were considered symptoms of pneumonia

and upper respiratory tract infection. There was no

history of haemoptysis.

At 36 months after the presentation, he was

admitted again for pallor, fatigue, and fever. This time,

he needed oxygen therapy. Chest was clear with mild

subcostal insucking. Hepatomegaly of 4 cm below the

costal margin was noted. Chest X-ray showed bilateral

reticulonodular haziness (Fig 1). Haemoglobin level was 61 g/L. Both MCV (78 fL) and MCH level (25 pg) were

in the lower normal limits. The serum ferritin level was

879 pmol/L. A diagnosis of pneumonia was made;

he was started on oral co-amoxiclav (amoxicillin and

clavulanic acid) and azithromycin and given blood

transfusion. Fever subsided and oxygen was weaned

off. Ultrasonography of abdomen performed 1

month later showed no hepatomegaly; mild hepatic

coarsening was suggestive of parenchymal disease.

Liver function tests were normal all along. However,

the patient tested positive for EBV immunoglobulin

(Ig) M antibodies. Thus, he was diagnosed to have

pneumonia with EBV infection.

Review of old CXRs showed similar

reticulonodular shadows. In view of his history of

recurrent iron-deficiency anaemia and CXR findings,

pulmonary hemosiderosis was suspected. Flexible

bronchoscopy was performed; bronchoscopic lavage

over left lingular and right middle lobe showed

blood-stained fluid. Bronchoalveolar lavage yielded

abundant hemosiderin-laden macrophages (HLM

index, 92%). High-resolution computed tomography

of thorax showed extensive ground glass opacities

and reticular shadows, suggestive of interstitial lung

disease. Diffuse visceral pleural brownish deposits

were noted over the entire left lung on video-assisted

thoracoscopy. Lung biopsy was performed to rule

out systemic disorders with pulmonary capillaritis,

which could cause diffuse alveolar haemorrhage

(DAH). These included Goodpasture’s syndrome, IgA

nephropathy, Wegener’s granulomatosis, systemic

lupus erythematosus, and antiphospholipid syndrome.

Biopsy of lung tissue showed numerous HLM. There

was no evidence of capillaritis or vasculitis. Absence

of fibrosis and negative exposure history also excluded

hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Immunostaining for

IgG, IgM, and IgA was negative. The overall picture

was compatible with pulmonary hemosiderosis.

Further blood investigations were performed to

exclude systemic causes of pulmonary haemorrhage

as stated above. Antiglomerular basement membrane

antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil

cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, anti-extractable

nuclear antibodies, and anti-cardiolipin

IgG antibodies were not detected. Furthermore,

the patient was negative for anti-transglutaminase

antibody for coeliac disease. He tested weakly

positive for IgE antibodies against cow’s milk.

Immunoglobulin pattern was unremarkable apart

from mildly raised IgA antibody level at 2.28 g/L

(range, 0.5-1.92 g/L). Renal function and urinalysis

were normal.

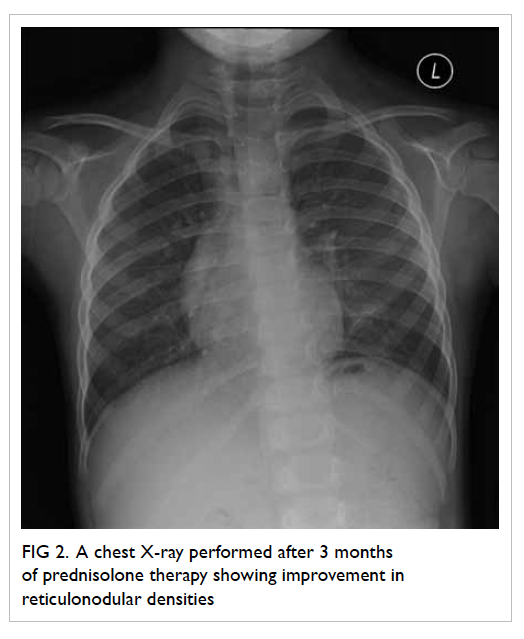

A diagnosis of IPH was made based on the

above findings. Oral prednisolone was started

after the diagnosis for disease control. Chest X-ray

performed after 3 months of prednisolone showed

improvement in reticulonodular densities (Fig 2). We

plan to monitor the disease with clinical symptoms,

Hb levels, LDH levels, CXRs, and spirometry.

Figure 2. A chest X-ray performed after 3 months of prednisolone therapy showing improvement in reticulonodular densities

Discussion

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis is a rare disease

in children with an unknown aetiology. The estimated

yearly incidence among Swedish children from 1960

through 1979 was 0.24 per 1 000 000 children.1 A

retrospective review of records from a tertiary

paediatric hospital in northern Taiwan noted five

cases over 25 years.2 Patients classically presented

with a triad of recurrent or chronic pulmonary

symptoms (cough, dyspnoea, wheeze, haemoptysis),

pulmonary infiltrates on CXR, and iron-deficiency

anaemia. Our patient had only anaemia without

obvious underlying causes. Subsequent CXR changes

led to the suspicion of IPH.

Serum ferritin has been traditionally taken

as a reliable surrogate marker of body iron stores.

Hypoferritinaemia is commonly used as a diagnostic

marker for iron deficiency.3 However, as it is an acute-phase reactant, abnormally raised serum ferritin level

may be seen during acute infection or liver disease

even in the presence of iron deficiency.4 In IPH,

iron study usually shows low serum iron with low

iron saturation, and microcytosis and hypochromia

in the blood picture. However, plasma ferritin level

can be normal or elevated in IPH because of alveolar

synthesis and release into the circulation and does

not reflect the iron deposits in the body.5 This makes

the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anaemia in IPH

difficult. We recommend the use of serum iron and

transferrin saturation (serum iron/TIBC) instead to

evaluate suspected iron-deficiency anaemia.4

Diagnosis of IPH is based on exclusion of other

causes of intrapulmonary haemorrhage and systemic

diseases. In the absence of systemic disease, findings

of HLM in bronchoscopic lavage or gastric aspirate/sputum along with chronic pulmonary symptoms

lead to a diagnosis of IPH. Lung biopsy is the gold

standard for diagnosis. We performed lung biopsy to

exclude pulmonary capillaritis, which is one of the

causes of DAH. Pulmonary capillaritis is a small-vessel

vasculitis, which can occur as an isolated

condition or in association with multiple systemic

vasculitides. Isolated DAH without identifiable

causation or associated disease is referred to as IPH.6

Daily oral corticosteroids or weekly

intravenous pulse methylprednisolone is commonly

used in the induction treatment of IPH. Other

immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine,

cyclophosphamide, and hydroxychloroquine have

also been used alone or in combination with oral

corticosteroids.7 8 9 10 11 Low-dose oral corticosteroids,

azathioprine, or methotrexate are used in

maintenance phase. As there is lack of large patient

series and inadequate follow-up in previous studies,

the prognosis of IPH remains unclear. However,

aggressive treatment with the use of corticosteroids

and immunosuppressive agents are associated with

a prolonged survival and improved prognosis.12

Long-term low-dose corticosteroid therapy was also

reported to result in a milder disease course and

prevent bleeding crisis.13

In conclusion, iron-deficiency anaemia results

from poor dietary intake of iron in infants and

toddlers. However, every child older than 24 months

presenting with iron-deficiency anaemia should be

evaluated for chronic blood loss. In this report, we

have illustrated that anaemia without any respiratory

symptoms can be the sole presenting feature of IPH,

preceding other signs and symptoms, especially in

young children. Haemoptysis may not be present in

young children with IPH, as they tend to swallow

their sputum. We recommend that when children

present with unexplained anaemia and bilateral lung

infiltrations, pulmonary haemorrhage should be

suspected.

References

1. Kjellman B, Elinder G, Garwicz S, Svan H. Idiopathic

pulmonary haemosiderosis in Swedish children. Acta

Paediatr Scand 1984;73:584-8. Crossref

2. Yao TC, Hung IJ, Wong KS, Huang JL, Niu CK. Idiopathic

pulmonary haemosiderosis: an Oriental experience. J

Paediatr Child Health 2003;39:27-30. Crossref

3. Rybo E. Diagnosis of iron deficiency. Scand J Haematol

Suppl 1985;43:5-39.

4. Li CH, Lee AC, Mak TW, Szeto SC. Transferrin saturation

for the diagnosis of iron deficiency in febrile anaemic

children. Hong Kong Pract 2003;25:363-6.

5. Ioachimescu OC, Sieber S, Kotch A. Idiopathic pulmonary

haemosiderosis revisited. Eur Respir J 2004;24:162-70. Crossref

6. Fullmer JJ, Langston C, Dishop MK, Fan LL. Pulmonary

capillaritis in children: a review of eight cases with

comparison to other alveolar hemorrhage syndromes. J

Pediatr 2005;146:376-81. Crossref

7. Milman N, Pedersen FM. Idiopathic pulmonary

haemosiderosis. Epidemiology, pathogenic aspects and

diagnosis. Respir Med 1998;92:902-7. Crossref

8. Rossi GA, Balzano E, Battistini E, et al. Long-term

prednisolone and azathioprine treatment of a patient with

idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. Pediatr Pulmonol

1992;13:176-80. Crossref

9. Colombo JL, Stolz SM. Treatment of life-threatening

primary pulmonary hemosiderosis with cyclophosphamide.

Chest 1992;102:959-60. Crossref

10. Zaki M, al Saleh Q, al Mutari G. Effectiveness of chloroquine

therapy in idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis. Pediatr

Pulmonol 1995;20:125-6. Crossref

11. Bush A, Sheppard MN, Warner JO. Chloroquine in

idiopathic pulmonary haemosiderosis. Arch Dis Child

1992;67:625-7. Crossref

12. Saeed MM, Woo MS, MacLaughlin EF, Margetis MF,

Keens TG. Prognosis in pediatric idiopathic pulmonary

hemosiderosis. Chest 1999;116:721-5. Crossref

13. Kiper N, Göçmen A, Ozçelik U, Dilber E, Anadol D. Long-term

clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary

hemosiderosis (1979-1994): prolonged survival with low-dose

corticosteroid therapy. Pediatr Pulmonol 1999;27:180-4. Crossref