Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Feb;25(1):30–7 | Epub 18 Jan 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Totally laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for

advanced gastric cancer: a matched retrospective cohort study

Brian YO Chan, MB, ChB, MRCSEd1; Kelvin

KW Yau, MStats, PhD2; Canon KO Chan, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)1

1 Department of Surgery, Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Management Sciences,

City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Canon KO Chan (chankoc@gmail.com)

A video clip illustrating totally

laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy for a patient with gastric cancer is available at www.hkmj.org

A video clip illustrating totally

laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy for a patient with gastric cancer is available at www.hkmj.orgAbstract

Introduction: Laparoscopic

gastrectomy revolutionised the management of gastric cancer, yet its

oncologic equivalency and safety in treating advanced gastric cancer

(especially that in smaller centres) has remained controversial because

of the extensive lymphadenectomy and learning curve involved. This study

aimed to compare outcomes following laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy

for advanced gastric cancer at a regional institution in Hong Kong.

Methods: Fifty-four patients who

underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy from January 2009 to March 2017 were

compared with 167 patients who underwent open gastrectomy during the

same period. All had clinical T2 to T4 lesions and underwent

curative-intent surgery. The two groups were matched for age, sex,

American Society of Anaesthesiologists class, tumour location,

morphology, and clinical stage. The endpoints were perioperative and

long-term outcomes including survival and recurrence.

Results: All patients had

advanced gastric adenocarcinoma and received D2 lymph node dissection.

No between-group differences were demonstrated in overall complications,

unplanned readmission or reoperation within 30 days, 30-day mortality,

margin clearance, rate of adjuvant therapy, or overall survival. The

laparoscopic approach was associated with less blood loss (150 vs 275

mL, P=0.018), shorter operating time (321 vs 365 min, P=0.003), shorter

postoperative length of stay (9 vs 11 days, P=0.011), fewer minor

complications (13% vs 40%, P<0.001), retrieval of more lymph nodes

(37 vs 26, P<0.001), and less disease recurrence (9% vs 28%,

P=0.005).

Conclusion: Laparoscopic

gastrectomy offers a safe and effective therapeutic option and is

superior in terms of operative morbidity and potentially superior in

terms of oncological outcomes compared with open surgery for advanced,

surgically resectable gastric cancer, even in a small regional surgical

department.

New knowledge added by this study

- This is the first study showcasing the efficacy and safety profile

of laparoscopic gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer in a small

regional surgical centre in Hong Kong.

- Laparoscopic gastrectomy was superior in terms of operative

morbidity and potentially superior in terms of oncological outcomes.

- Laparoscopic gastrectomy is a viable first-line treatment for

surgically resectable advanced gastric cancer.

- This study could spark a paradigm shift in other local surgical

departments and specialist training centres.

Introduction

With an age-standardised incidence rate of 24.2 per

100 000 population, gastric cancer is a major clinical entity in Eastern

Asia.1 Operative resection remains

the only curative treatment available. Over the years, advances in

minimally invasive surgery have caused a paradigm shift towards

laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG), with high-quality evidence from both the

East and West demonstrating a satisfactory safety profile and enhanced

postoperative recovery related to reduction of surgical trauma.2 3

However, one major concern regarding LG is its

oncologic equivalency compared with the open technique, as LG requires

adequate lymphadenectomy and involves a steep learning curve. Several

overseas studies have shown comparable lymph node harvest and survival

data2 3

4 but are limited by either short

follow-up periods or being published by major centres in Korea or Japan,

where extensive experience is available. Whether or not these results are

reproducible in smaller regional centres is unknown, especially in Hong

Kong, where no comparative studies concerning LG for gastric cancer exist

in the literature. It has been suggested that a case volume of

approximately 50 to 60 LGs is required to achieve proficiency, with

demonstrable decreases in blood loss, conversion rate, and hospital length

of stay (LOS) with increasing experience.5

Furthermore, most of these data were based on operations for early gastric

cancer in patients selected according to strict criteria. In advanced

cases requiring extensive lymphadenectomy, evidence is still emerging, and

the learning curve may be steeper.

At our regional surgical centre in Hong Kong, LG is

currently the first-line modality in the absence of contra-indications. We

aimed to perform a matched retrospective cohort study of laparoscopic

versus open gastrectomy for resectable advanced gastric adenocarcinoma of

all sites, comparing intra- and peri-operative characteristics,

oncological clearance, and long-term outcomes including survival and

recurrence.

Methods

Study design and participants

A prospective gastric cancer database was

maintained at the Department of Surgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital. From

January 2009 to March 2017, 221 patients who underwent curative

gastrectomy for advanced gastric adenocarcinoma (ie, clinical T2 to T4

lesions of all sites) were identified. Clinical T1 lesions (n=23); cases

with pathologies other than adenocarcinoma, like high-grade dysplasia

(n=1); squamous cell carcinoma (n=2); neuroendocrine tumours (n=4);

gastrointestinal stromal tumours (n=3); and cases involving conversion of

approach (n=6) were excluded. A total of 54 patients operated via a

totally laparoscopic approach were identified and matched with 167

patients who underwent the same operation via an open approach during the

same 8-year period. The case ratio between the laparoscopic and open

groups was 1:3.09. Patients from both groups were matched in terms of age,

sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, tumour location,

morphology, and clinical stage. Follow-up was performed on all subjects at

the Upper Gastrointestinal Surgical Specialist Outpatient Clinic of our

hospital at 3-month intervals up to 2 years postoperation and every 6

months thereafter.

Operative technique

All 54 LG and 167 open operations were performed by

two experienced upper gastrointestinal surgeons with experience of more

than 100 gastrectomy operations each. The choice of approach was decided

by the attending surgeon. All subjects underwent radical gastrectomy with

D2 lymph node dissection as per the guidelines of the Japanese Gastric

Cancer Association6; that is, in

addition to the perigastric nodes, a second tier of lymph nodes along the

celiac axis branches were removed. Distal subtotal, proximal, or total

gastrectomy was selected depending on tumour location and macroscopic

characteristics. Splenectomy or distal pancreatectomy was performed if

there was direct invasion with the possibility of en bloc complete

resection.

Under general anaesthesia, with the patient in

supine split leg position, LG was performed with the surgeon operating on

either side of the patient and a camera assistant in the middle.

Pneumoperitoneum was created via the open Hasson technique at a pressure

of 12 mm Hg, followed by insertion of a 12-mm infra-umbilical camera port,

then one 12-mm and one 5-mm working port in each upper quadrant of the

abdomen for a total of five ports.

Distal and total gastrectomy accounted for 98% of

all LGs performed. Hence, our discussion of technique shall focus on them.

For total gastrectomy, entry to the lesser sac was obtained via dissection

of the avascular plane between the greater omentum and transverse

mesocolon. The gastrocolic ligament was divided proximally and then

distally towards the pylorus using a laparoscopic energy device. The right

gastroepiploic vessels were doubly clipped and divided at their origin.

Then, dissection of the hepatoduodenal ligament was performed, with

division of the right gastric artery and transection of the duodenum with

a linear stapler. The dissection continued towards the gastroesophageal

junction along the lesser curvature. Along with that dissection,

simultaneous D1 lymphadenectomy of the perigastric nodes was performed.

Then, D2 lymphadenectomy was performed, with removal of the common hepatic

artery (Station 8) nodes. The root of the left gastric artery was doubly

clipped and then divided, followed by dissection of celiac trunk (Station

9) and left gastric artery (Station 7) nodes. The splenic artery lymph

nodes (Station 11) and hilar nodes (Station 10) were excised together with

the surrounding fatty connective tissues. During distal gastrectomy, the

left cardia (Station 2), greater curvature (Station 4sa), splenic hilum

(Station 10), and distal splenic artery (Station 11d) nodes were left

intact.

After adequate mobilisation, the stomach or distal

oesophagus was divided using a linear stapler with several centimetres of

margin, and the surgical specimen was placed in an endobag for later

retrieval. Following total gastrectomy, oesophagojejunal anastomoses were

fashioned end-to-side using a circular stapler and a transoral anvil

device, whereas distal gastrectomy reconstruction was performed by either

Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy or delta-shaped Billroth I anastomosis.

Side-to-side oesophagogastrostomy was utilised in cases of proximal

gastrectomy.

Open gastrectomies followed standard procedures

from the surgical literature and were characterised by a wider range of

reconstructive techniques in our study.

Outcome variables and bias

All clinical data originated from the patients’

electronic and handwritten medical records and were recorded into the

prospective gastric cancer database by one principal investigator. Recall

and observer bias were addressed by this approach. Selection bias was

minimised by matching and controlling for covariates in the outcome

analyses. Our pathological staging followed that of the American Joint

Committee on Cancer (AJCC) for gastric cancer. Complications were graded

from 1 to 5 according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, with 1 to 2

being minor complications and 3 to 5 being major complications. We defined

30-day mortality as any death, inside or outside of the hospital, within

30 days of surgery. Recurrences were documented as either local or

distant, depending on the first recognised disease site. We designated

survival time as the time from the date of the operation until death or

the last available follow-up (if the patient did not experience an event

of interest).

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using the

SPSS (Windows version 22.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Frequency matching was employed to ensure that the laparoscopic and open

groups had equal distributions of age, sex, ASA class, tumour location,

morphology, and clinical stage. Appropriate univariate analyses like the

Mann-Whitney U test were selected to examine continuous variables,

whereas Chi squared and Fisher’s exact tests were run for dichotomous and

categorical variables, respectively. Operative outcomes like blood loss,

operating time (OT), type of operation, complications, 30-day mortality,

LOS, and oncologic outcomes such as margin clearance, pathological stage,

lymph node yield, adjuvant treatment, survival time, and disease

recurrence were compared. Survival probabilities were estimated using the

Kaplan-Meier method and compared using stratified log-rank tests. All P

values were based on two-tailed statistical analyses with P<0.05 as the

threshold for statistical significance. All percentages were rounded off

to nearest integer.

Results

Baseline demographics

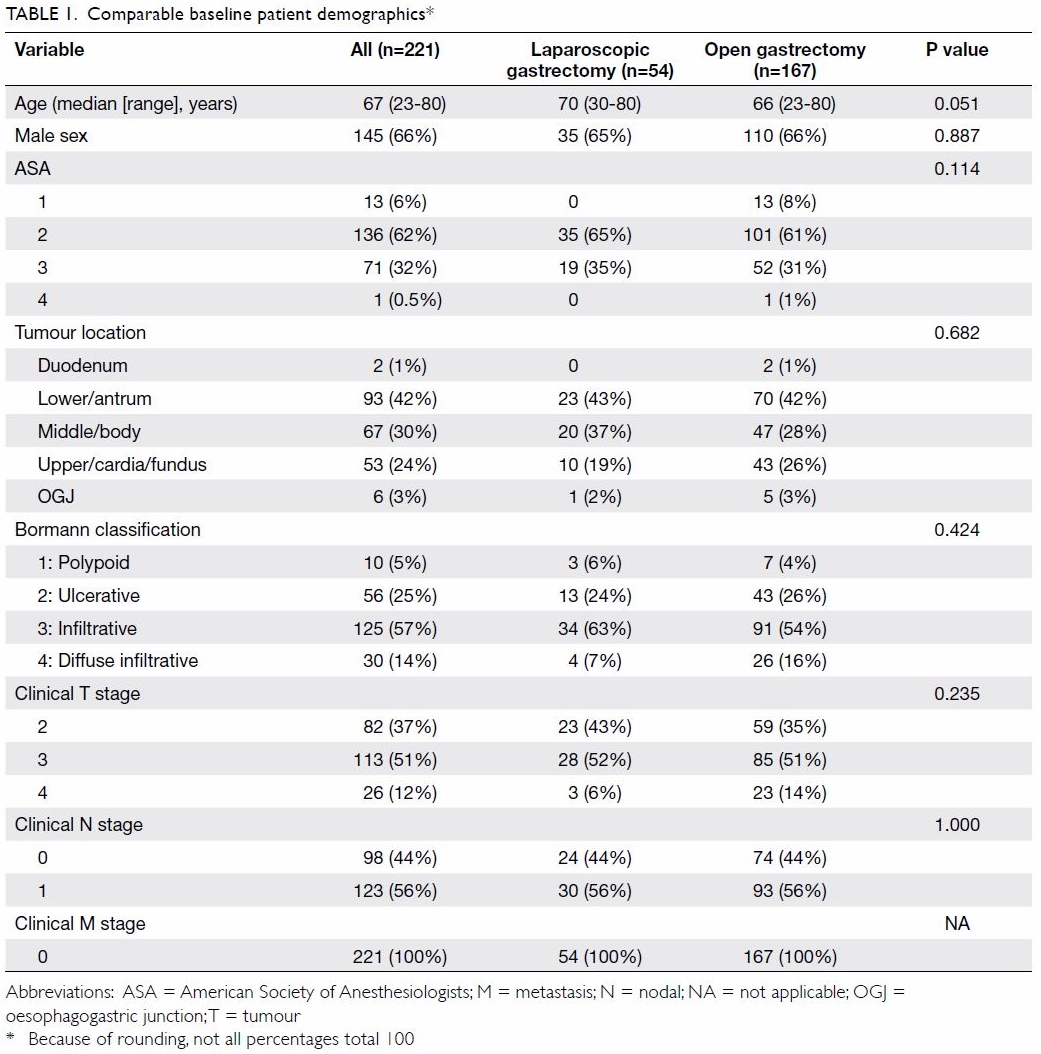

A total of 221 matched patients were evaluated. The

median age at the time of operation was 67 years (range, 23-80 years),

with the majority of patients (145, 66%) being male. Most patients (62%)

were in the ASA 2 category (ie, mild systemic disease without functional

limitation).

In order of descending frequency, 42% of the

tumours were located in the antrum, followed by the gastric body (30%) and

cardia/fundus (24%). All 221 patients had advanced gastric cancer

according to the AJCC clinical staging. Clinical T3 and T2 lesions

accounted for 51% and 37% of cases, respectively, and the remaining 12%

were category T4. Macroscopically, 70% of the tumours were of Bormann

types 3 or 4; only 30% were types 1 or 2 (ie, polypoid or ulcerative with

clear margins). Of all the investigated subjects, 56% had N1 disease on

imaging, while the rest (44%) were negative. No subject had clinically

detectable metastases.

No statistically significant differences were

demonstrated in any of the six matching parameters between the

laparoscopic and open patient groups. The details of the subjects’

demographic variables are charted in Table 1.

Operative outcomes

All 221 patients underwent D2 lymphadenectomy. The

frequency of operation type was comparable between distal and total

gastrectomy (43% and 53%, respectively). Distal pancreatectomy was

performed in six (4%) subjects in the open group only, with no

statistically significant difference between groups (P=0.340). Splenectomy

was performed in 10 (6%) versus 0 subjects in the open and laparoscopic

groups, respectively, and this difference was not statistically

significant (P=0.124). The history of laparotomy was comparable between

groups (7% vs 11% for the laparoscopic and open groups, respectively,

P=0.606).

The laparoscopic group had shorter median OT (321

vs 365 min, P=0.003) and less intra-operative blood loss (150 vs 275 mL,

P=0.018). Operative complications were observed in 41% and 51% of

laparoscopic and open cases, respectively; this trend seemed to favour the

laparoscopic group but failed to reach statistical significance (P=0.210).

Subgroup analyses showed that fewer minor complications were demonstrated

in the laparoscopic group (13% vs 40%, P<0.001). One case of open

distal gastrectomy and laparoscopic total gastrectomy each accounted for

the 30-day mortality among all subjects. Both were older adults in their

70s who developed sudden cardiac arrest and cerebrovascular accident,

respectively, in the days after operation. The median postoperative LOS

was 9 and 11 days, significantly shorter in the laparoscopic group

(P=0.011).

Pathological characteristics

Tumour location and clinical stage were comparable

between groups, as they were matching variables. All patients had

adenocarcinoma. Margin clearance was satisfactory, ranging from 96% to 98%

in the laparoscopic group and 94% to 96% in the open group, and the P

value showed no significant between-group difference in this metric. Over

half (57%) of the patients were in pathological stage III, with no

significant difference in staging between the groups. Interestingly, the

median number of lymph nodes harvested was higher in the laparoscopic

group at 37 (range, 7-77) compared with 26 (range, 3-95) in the open group

(P<0.001). Adjuvant treatment was prescribed in 41% (22 of 54) of

laparoscopic group patients versus 28% (47 of 167) of open group patients,

but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.093).

Oncological outcomes

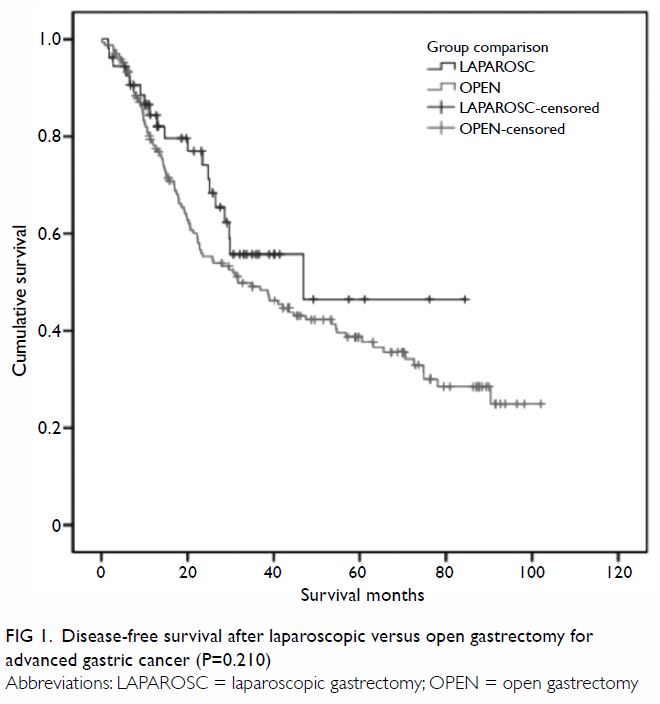

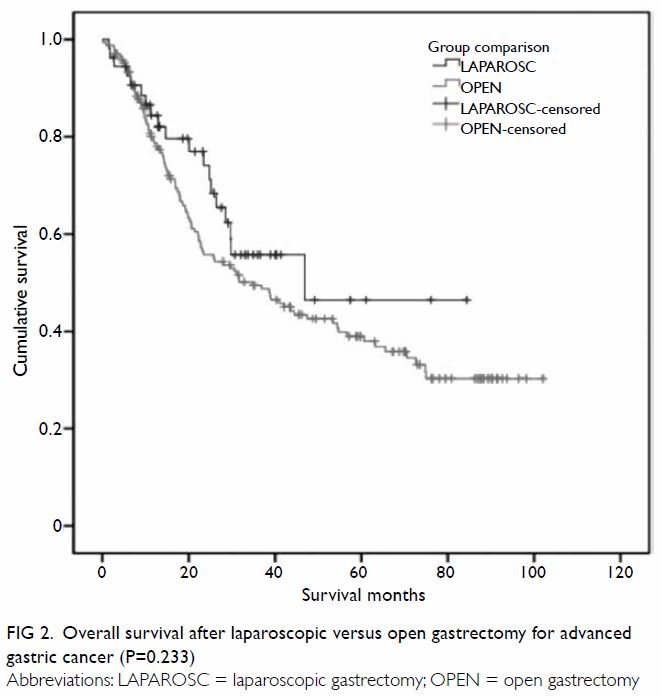

The mean postoperative follow-up duration was 33

months (laparoscopic group: 25 months, open group: 35 months). Disease

recurrence was observed in 9% and 28% of laparoscopic and open group

patients, respectively, with a statistically significant between-group

difference (P=0.005). During the entire follow-up period, death occurred

in 19 out of 54 laparoscopic group (35%) and 97 out of 167 open group

(58%) patients. Median disease-free survival (DFS) was 46.9 months and

31.7 months, and median overall survival (OS) was 46.9 months and 34.9

months, for the laparoscopic and open groups, respectively. Using a

60-month cut-off, the estimated 5-year DFS and OS were both 47% for the

laparoscopic group and 39% for the open group (P=0.210 and P=0.233,

respectively). The details of the operative, pathological, and oncological

outcomes are charted in Table 2, and the Kaplan-Meier plots for DFS and OS

are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1. Disease-free survival after laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer (P=0.210)

Figure 2. Overall survival after laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer (P=0.233)

Discussion

Laparoscopic gastrectomy has markedly matured since

its inception by Kitano et al7 in

1994. In early gastric cancer, high-quality evidence including

meta-analyses has demonstrated the equivalence of laparoscopic distal

gastrectomy and open surgery. Early postoperative benefits include less

blood loss, fewer complications, and shorter LOS with comparable

mortality. However, lengthier operations and smaller lymph node yield

remain issues in the laparoscopic approach.8

Technical difficulties in anastomosis and laparoscopic lymph node

dissection have resulted in poorer translation of these results to total

gastrectomies, and such application is often practised only in expert

centres with exceptional case volume.9

Similar controversies also exist in the field of advanced gastric cancer,

where adequate lymphadenectomy is of the utmost importance. Acceptable

short-term outcomes have been reported only in studies that incorporated

experienced surgeons, with the technique’s long-term safety still unknown.10 11

12

As such, the safety and oncologic efficacy of LG

are influenced to a large extent by regional incidence and the case volume

of individual centres. With an age-standardised incidence rate of 9.1 per

100 000 population in Hong Kong, compared with 41.8 per 100 000 population

in Korea and 24.2 per 100 000 population overall in Eastern Asia, gastric

carcinoma is far from the top in terms of cancer incidence ranking.1 13 While this

low age-standardised incidence rate may be partially explained by the

absence of population-wide screening, this lack of screening also implies

that a higher proportion of patients will present with advanced disease.

These two points, together with the absence of studies evaluating LG in

the local literature, mark the importance of our study in evaluating the

efficacy and safety of such procedures in treatment of advanced gastric

cancer in Hong Kong.

Queen Elizabeth Hospital, the largest acute

hospital in Hong Kong and a tertiary surgical referral centre, has a

significant case volume and a patient pool that is representative of the

local population. Through this study, we aimed to document the local Hong

Kong experience, comparing and contrasting results from Hong Kong with

those from overseas expert centres.

In accordance with other major studies, we

demonstrated that LG was associated with less blood loss, fewer minor

complications, and shorter LOS while achieving similar overall levels of

complications and operative mortality to open surgery. The lesser degrees

of pain, blood loss, ileus, and surgical site infections associated with

laparotomy than open surgery are well-investigated benefits of the

laparoscopic approach, and this explains the scarcity of minor

complications.3 8 Median postoperative LOS was 2 days shorter after LG

than open surgery, a small but statistically significant difference. No

local data on average post-gastrectomy LOS exist, but our results are

comparable with an LOS of 11 days (range, 8-12.5 days) observed in the

United Kingdom.14 The small

difference in LOS between the laparoscopic and open groups may be

partially explained by the fact that, compared with Western counterparts,

local Chinese patients prefer in-patient care over community care despite

being fit for out-patient treatment. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery

(ERAS) protocols have been gradually adapted in local surgical units in

recent years, but no data on their efficacy in gastrectomy patients have

been reported.15 With wider

implementation of ERAS and better patient education, it is expected that

differences in LOS between types of surgery will become even more

apparent.

About half (53%) of the operations performed in

this study were total gastrectomies, and all patients had advanced gastric

cancer; both of these factors have been associated with longer OT in the

literature.16 The OT inherent to

the laparoscopic approach has been reported as longer in many studies, but

the median OT of LG was 44 minutes shorter than that of open surgery in

our series. This may be partly explained by the more complex procedures

expected in patients chosen for open gastrectomies. For example, en bloc

splenectomy and distal pancreatectomy were only performed in the open

group, despite the between-group differences in frequency not reaching

statistical significance. Further, the overall histories of laparotomy,

tumour location, and clinical and pathological staging were comparable

between the two groups. Another explanation for the shorter OT observed in

LG in our study is the maturation of our surgeons’ laparoscopic technique.

The higher ratio of total gastrectomies (50%-54%) compared with literature

values was caused by pathological characteristics and surgeon preference.

The 42% of cases with distally located tumours accounted for a compatible

43% of cases in which distal gastrectomies were performed. In contrast,

for the remaining tumours in the gastric cardia or body, because 70% of

tumours were Bormann types 3 and 4, total gastrectomy was the curative

operation of choice.

The median number of lymph nodes harvested was

significantly higher in the LG group (37 compared with 26 in the open

group). Both groups had more lymph nodes harvested than the 15 required

for proper staging. Laparoscopic D2 lymphadenectomy is a technically

challenging procedure, especially at Stations 4, 6, 9, and 11 and in

spleen-preserving lymphadenectomy at the splenic hilum. However, advances

in optics have offered unparalleled amplified clarity for identification

of anatomical structures. The latest laparoscopic energy devices have also

enabled pinpoint precision while performing dissection and sealing in

extensive lymphadenectomies.17

With time and experience, there are indications that our centre’s surgeons

have overcome the learning curve involved.

The importance of adjuvant chemotherapy in curing

advanced gastric cancer cannot be undermined, as many cases have occult

micrometastases. Yet, it has been reported that only 48% to 67% of

patients indicated for adjuvant chemotherapy had it successfully

administered, with postoperative morbidity being a significant factor

behind this deficiency.3 The

advantages of fewer minor complications, shorter LOS, and overall better

general condition of patients may potentially benefit those who undergo LG

and are eligible for adjuvant therapy. Such eligibility was shown in 41%

of patients who underwent LG versus 28% in the open group, but the

difference barely fell short of reaching statistical significance

(P=0.093). Higher rates of receiving adjuvant treatment may translate into

the significantly lower disease recurrence of 9% in the LG group compared

with 28% in the open group (P=0.005). No differences in 5-year DFS nor OS

were demonstrated between the groups. Further large-scale, multicentre

randomised controlled trials like the Korean Laparo-endoscopic

Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS-02; registered at

www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01456598), the Japanese Laparoscopic Gastric

Surgery Study Group (JLSSG 0901; registered at www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/ as

UMIN000003420), and the Chinese Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery

Study (CLASS-01; registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01609309) are

needed to elucidate the short- and long-term results of LG for advanced

gastric cancer.

The limitations of our study include its

retrospective and single-centre nature and its limited number of

participants and follow-up period. Anticipated en bloc distal

pancreatectomy and splenectomy were handled exclusively via the open

approach in this series. With increasing experience, it may be possible to

perform these adjunct procedures laparoscopically, yielding more

homogenous groups for comparison. Efforts have been made to minimise

recall and observer bias and to reduce selection bias through matching.

In summary, LG was associated with shorter OT, less

blood loss, fewer minor complications, shorter LOS, higher lymph node

yield, and, importantly, lower rates of disease recurrence. Overall

complications, 30-day mortality, margin clearance, pathological stage,

percentage receiving adjuvant therapy, and survival time were comparable

between groups. Despite this study’s retrospective cohort nature, which

limits its generalisability, because of the characteristics of our patient

base and the level of our hospital, we believe that our results are

representative of the latest Hong Kong experience.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic gastrectomy is effective and safe as a

curative treatment for patients with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma in

Hong Kong. Apart from its overall equivalent operative and oncological

outcomes, it benefited patients by being associated with less morbidity,

shorter LOS, and higher lymph node clearance than open surgery. This

represents the first local study of its type and illustrates the maturity

of LG as a first-line treatment in our surgical department.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept and design of study: All authors.

Acquisition of data: BYO Chan, CKO Chan.

Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of manuscript: BYO Chan.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: BYO Chan, CKO Chan.

Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of manuscript: BYO Chan.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Hospital Authority

Kowloon Central Cluster/Kowloon East Cluster Research Ethics Committee

(Ref No. KC/KE-18-0100/ER-1).

References

1. International Agency for Research on

Cancer, World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.1, cancer incidence

and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. 2014. Available from:

http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 1 Jun 2018.

2. Wang JF, Zhang SZ, Zhang NY, et al.

Laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for elderly patients with

gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol

2016;14:90. Crossref

3. Kelly KJ, Selby L, Chou JF, et al.

Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma in the

west: a case-control study. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3590-6. Crossref

4. Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, et al. Long-term

results of laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a large-scale

case-control and case-matched Korean multicenter study. J Clin Oncol

2014;32:627-33. Crossref

5. Gholami S, Cassidy MR, Strong VE.

Minimally invasive surgical approaches to gastric resection. Surg Clin

North Am 2017;97:249-64. Crossref

6. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association.

Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric

Cancer 2011;14:101-12. Crossref

7. Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi

K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc

1994;4:146-8.

8. Viñeula EF, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Coit

DG, Strong VE. Laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy for gastric

cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and high-quality

nonrandomized studies. Ann Surg 2012;255:446-56. Crossref

9. Son T, Hyung WJ. Laparoscopic gastric

cancer surgery: current evidence and future perspectives. World J

Gastroenterol 2016;22:727-35. Crossref

10. Wei HB, Wei B, Qi CL, et al.

Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for

gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech

2011;21:383-90. Crossref

11. Uyama I, Suda K, Satoh S. Laparoscopic

surgery for advanced gastric cancer: current status and future

perspectives. J Gastric Cancer 2013;13:19-25. Crossref

12. Shinohara T, Satoh S, Kanaya S, et al.

Laparoscopic versus open D2 gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a

retrospective cohort study. Surg Endosc 2013;27:286-94. Crossref

13. Hospital Authority. Hong Kong Cancer

Registry. Available from: www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg. Accessed 1 Jun 2018.

14. Tang J, Humes DJ, Gemmil E, Welch NT,

Parsons SL, Catton JA. Reduction in length of stay for patients undergoing

oesophageal and gastric resections with implementation of enhanced

recovery packages. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013;95:323-8. Crossref

15. Mortensen K, Nilsson M, Slim K, et al.

Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced

Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Br J Surg

2014;101:1209-29. Crossref

16. Nozoe T, Kouno M, Iguchi T, Maeda T,

Ezaki T. Effect of prolongation of operative time on the outcome of

patients with gastric carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2012;4:119-22. Crossref

17. Rosati R, Parise P, Giannone

Codiglione F. Technical pro & cons of the laparoscopic

lymphadenectomy. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;1:93. Crossref