© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

HEALTHCARE FOR SOCIETY

The Hong Kong Hospital Authority reform: a historical perspective

Part 2: From reform blueprint to practice

Part 2: From reform blueprint to practice

William SW Ho, FCSHK, FHKCCM

Hong Kong College of Community Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

Preface

The previous article (Part 1) in this series1 describes

the historical transition of Hong Kong’s public

hospital system from being part of the Civil Service

to a separate corporatised entity established by

statute, charged with modernising its management

and service quality. After the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority (HA) was inaugurated on 1 December

1990, it took merely 12 months of preparation for

the takeover of the entire public hospital system

overnight on 1 December 1991. This article describes

how the Authority turned the ambitious blueprint

laid down in the Scott Report,2 further modified and

elaborated in the Provisional Hospital Authority

(PHA) Report,3 into reality.4 Current HA staff may

be amazed that so many systems and processes that

have long been taken for granted were once non-existent.

This historical account may give not only

an understanding of how the existing practices came

about, but also a useful case study in healthcare

organisational management.

Comprehensive reform dimensions

Mission and strategies

For the first time, the public hospital system

had a mission statement as laid down by the HA

Board after a 3-day workshop in February 1991,5

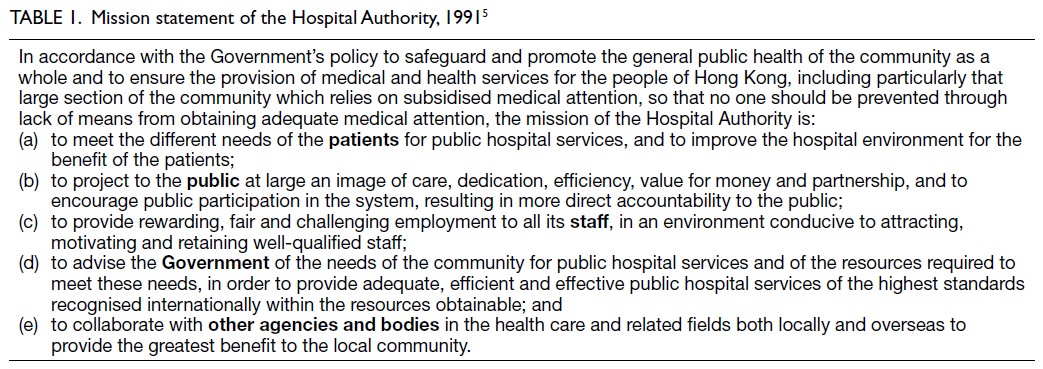

developed according to the organisational function spelt out in the HA Ordinance (Table 1). This

rather lengthy mission statement merely reiterates

upfront the communitarian healthcare policy of

the Government, and goes on to enunciate the

Authority’s responsibility towards each of the major

stakeholder parties.

From this first version of the mission

statement, major strategies were derived, which

served to focus the whole organisation on priority

goals and targets to improve population health and

service quality. This was a far cry from the past,

when there were hardly any coordinated directions

beyond simple bed-to-population or manpower

ratios to cope with population growth, and where

service improvements were heavily influenced by

the preferences of powerful medical consultants and

their respective political clout in securing resources

within the former Medical and Health Department.

Three levels of governance

Empowered by the HA Ordinance, the Government-appointed

Members of the HA (commonly referred

to collectively as the HA Board) governed all

public hospitals independently of the Civil Service,

thus enjoying much greater flexibility in the use

of available funds and the management of human

resources, while accountable to the Secretary for

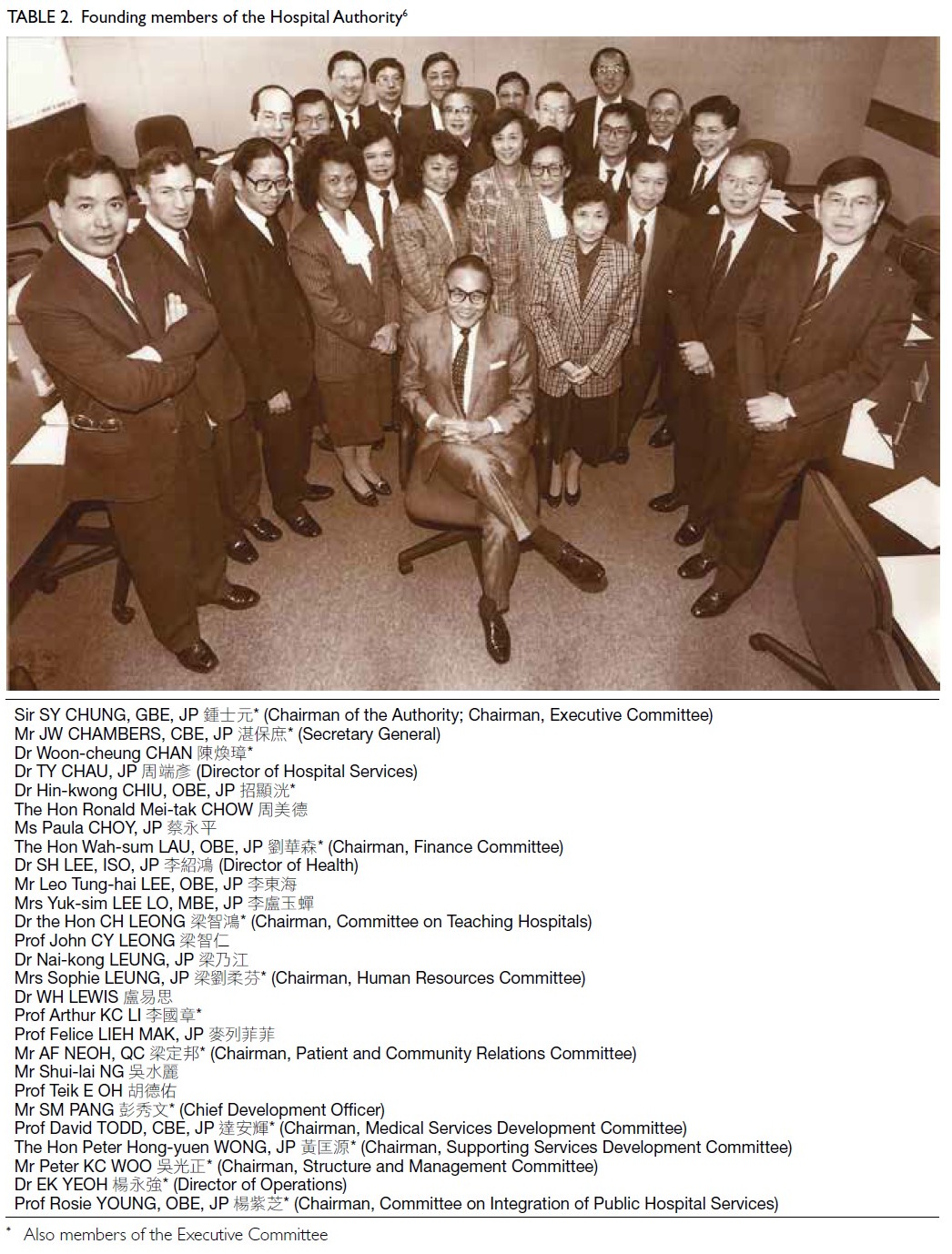

Health and Welfare. The Chairman of the PHA, Sir Sze-yuen Chung 鍾士元爵士, was reappointed as

Chairman of the HA (Table 26).

Eight functional committees under the HA

Board served to introduce external expertise

and steer managerial modernisation in specific

areas. The chairmen and vice-chairmen of these committees together with the three principal officers

constituted an Executive Committee, which was the

chief decision-making body of the Authority chaired

by the HA Chairman. In addition, an independent

Public Complaints Committee was established to

deal with appeal cases not settled at the hospitals.

At the second level, three Regional Advisory

Committees were established to enable community

participation. At the third level, each hospital was

governed by a Hospital Governing Committee with

the introduction of community leaders. For Schedule

2 (ex-subvented) hospitals, the parent body would

nominate a two-thirds majority of the members

(with the rest appointed by the HA) and would chair

the Hospital Governing Committee.

Two levels of management

The previous three-tiered structure of the Medical

and Health Department—Headquarters, Regional

Offices, and Hospitals—was simplified into two

levels to enhance efficiency and hospital autonomy.

The Regional Offices were abolished with their staff

absorbed into the HA Head Office.

Management structure: Head Office level

A tripartite top management structure of principal

officers—Director of Operations, Chief Development

Officer, and Secretary General—was initially

adopted, reporting to the Executive Committee

of the HA Board, until a suitable candidate for the

Chief Executive (CE) position emerged.

The appointment of the three principal officers

was completed upon the HA’s establishment on 1

December 1990. There was a balanced mix of talents.

The Director of Operations, Dr EK Yeoh 楊永強, was

a senior medical consultant recruited from within the

system. The Chief Development Officer, Mr SM Pang

彭秀文, was an experienced hospital administrator

recruited from Australia. The Secretary General, Mr

John Chambers 湛保庶, was former Secretary for

Health and Welfare from the Administrative Officer

rank of the Civil Service. Recruitment of various

deputies was also completed by the time the HA

formally took over the operations of all hospitals on

1 December 1991. Dr Yeoh was eventually appointed

to the CE position in 1994.

Management structure: Hospital level

Under the new management structure, each hospital

was headed by a Hospital Chief Executive (HCE),

with more power and autonomy than the previous

Medical Superintendents, and assisted by a number

of General Managers in clinical and business

functions. The HCEs reported directly to the CE

of the HA. Appointment of HCEs went through

a nurturing process, assisted by a Management

Transformation Implementation Task Force from the

Head Office. The first batch of HCEs was appointed

in March 1992, and appointments for all other

hospitals were largely completed within 3 years.

Eighteen of the newly appointed HCEs were senior

doctors, reflecting a major effort by the HA to bring

new blood into management roles from clinicians within the system. Seventeen other HCEs were

former Medical Superintendents, and four HCEs of

smaller hospitals came from nursing or allied health

backgrounds.7 Internal hospital appointments to new

management positions and structural remodelling

followed accordingly.

Each clinical department was headed by a

Chief of Service, who reported to the HCE, and was

assisted by a Departmental Operations Manager

(DOM) who would be a senior nurse.8 Each ward

was headed by a Ward Manager, also a senior nurse,

who reported to the DOM. All nurses working in a

clinical department therefore ultimately reported

to the Chief of Service as part of an integrated

multidisciplinary team, rather than to the Chief

Nursing Officer in a hierarchical manner as in the old

days. The General Manager (Nursing), who replaced

the Chief Nursing Officer position, became part of

the HCE’s top management team and no longer held

line authority over the DOMs.

Under the new management culture, an inverted

pyramid model was advocated, where frontline

clinical units were regarded as the most important

and better supported by the revamped management

structure and capabilities.9 Decentralisation of

decision making and participatory management

were to be encouraged.

Staffing

No reform would be successful by merely putting

old wine in new bottles. Whatever new mission

statement, management positions, systems and

processes were put in place would need to be

embraced and operationalised by the very people

within the system. Given the staff unions’ animosity

towards the old regime and suspicion of the new,

as reflected in Part 1 of this series,1 winning them

over was of utmost importance. An attractive new

remuneration package would be a crucial first

step. On the other hand, as the Government would

ultimately shoulder the HA’s staff costs, consideration

should be given to the long-term financial burden

and comparability with Civil Service terms.10 Both

fronts had to be tackled by the HA.

Under the principle of “what the total cost to

Government of running the service would be had all

staff been given Civil Service terms”, the approach was

taken to divide all staff in the former Government

hospital system into pay bands for separate analysis,

as the ‘fringe benefits’ differed across bands. An

arbitrary snapshot of the situation as at 1 April 1989

was taken to calculate the total cost per staff band,

divided by the number of staff members to yield the

averaged-out cost per staff member in that band.

This would form the basis for constructing the new

HA staff terms ‘at comparable cost’.11

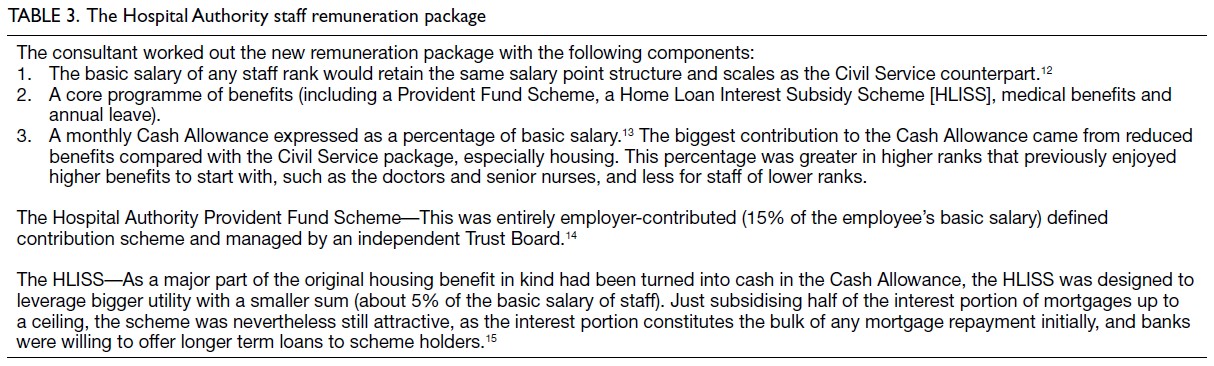

The PHA engaged Tower, Perrin, Forster

and Crosby to develop a new HA remuneration package (Table 312 13 14 15). To increase its attractiveness,

the idea was to change the pension portion into a

Provident Fund arrangement that would be invested

to generate a higher yield, and to reduce housing

and other ‘in kind’ benefits so as to translate more

of these into cash. Amid the booming economy at

the time, immediate cash, despite the ‘averaging

out’ effect, was often more attractive than potential

in-kind benefits, and certainly much more flexible

for the staff. Whether existing staff would choose to

switch over was a matter of individual consideration.

Having settled the new HA terms, another

challenge arose concerning the ‘bridging over’

arrangement for Civil Servants in Schedule 1 (ex-Government) hospitals opting into the new terms.

Unlike staff employed in Schedule 2 (ex-subvented)

hospitals who could simply take out their respective

provident fund balances from their previous

employers to join the new HA package, those working

in Schedule 1 hospitals were mostly on permanent,

pensionable terms. The staff unions hoped for

some kind of ‘pay-off’ to sever the link with the

Civil Service before switching over to the new HA

package. This would however incur a large sum of

upfront payment from the Government. Moreover,

not all staff would work to retirement age and attract

a pension. The idea of a deferred pension emerged,

namely, one only obtainable upon retirement from

the HA and computed using the same methodology

of years of service (as Civil Servants) and the last

salary drawn before switching over to HA term.16

All existing staff were given an irrevocable

choice within 3 years to switch to the new HA terms

or remain in their existing terms. Irrespective of

terms, all would be subject to the same management

on a fair basis within the HA. By the end of the

option period, 99.5% of Schedule 2 hospital staff

and 58.1% of Schedule 1 hospital staff changed over

to the new terms, giving an overall figure of 74.8%.

The generally inferior original employment terms

in various Schedule 2 hospitals compared with their Civil Service counterparts explained the former’s

high conversion rate. Among former Civil Servants

in the system, lower-ranking staff bands with less

to gain from the new package tended to record

fewer switching. Some also suspected that staff on

HA terms might have less job security than Civil

Servants ‘protected’ by their strong unions.

For clarity, all new hires after the HA

took over operation of all public hospitals on 1

December 1991 were only offered the HA terms of

employment. Settling staff terms of employment

was just a prerequisite, raising staff understanding

and performance in the management reform was

most important to ensure success. Major resources

were thereby committed to support tailored

management training courses for senior, middle

and frontline clinical staff, equipping them with

the concepts and know-how to carry out their

new roles. Additional resources were put into the

professional training of clinical staff to enhance their

competence, job satisfaction and retention. There

were also specific training courses for other staff to

uplift their performance in areas such as customer

service and complaints management. Expansion

of management functions also meant introduction

of external expertise in a host of non-clinical areas

such as information technology (IT), finance, legal,

engineering, human resources and other areas of

general management.

With improved staff packages, training and

professional advancement opportunities, there was

an atmosphere of progression and high morale in

the new organisation. As a result, staff wastage rate

quickly dwindled.

Direct patient service improvements

On clinical services, task forces were formed to tackle

overcrowding, waiting time, accident and emergency

service improvements, nursing services, and more

on a territory-wide basis. Clinical Coordinating

Committees were formed for each clinical specialty to foster inter-hospital collaboration and service

planning to improve system-wide performance in

quality and efficiency.

Priority areas of improvement included better

inter-hospital cooperation for patient diversion

from the most severely overloaded Schedule 1

hospitals to Schedule 2 hospitals, as well as better

bed management within each hospital, resulting in

drastic reduction in ‘camp beds’. A triage system

was implemented in all accident and emergency

departments to ensure minimal waiting time for

urgent cases. Computerised booking system for

Specialist Outpatient Clinics and doubling of

effort to increase throughput led to shorter waiting

lists and improved access to specialist care. New

signages, open counters, upgraded furniture and

hospital environment, as well as air-conditioning

projects also completely transformed the image of

public hospitals.

Infrastructure and capacity building

The Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital

was completed in 1993, eventually adding more

than 1800 beds to the eastern part of Hong Kong

Island. In view of the low bed-to-population ratio

in northern New Territories, the HA planned and

built the North District Hospital, which opened in

1998. There were numerous other additional blocks,

extensions, and improvement projects for existing

hospitals. Investment in major equipment included

the first magnetic resonance imaging machine in the

public system installed at Queen Elizabeth Hospital,

and additional computerised tomography scanners

in major hospitals, etc.

Information technology

There were hardly any major IT systems in use

in public hospitals before the HA, save for very

basic ones for payroll and accounting. There was

massive investment to revamp these systems and

to build many other essential systems for patient

registration and appointments, billing and revenue

collection, medical records tracing, pharmaceutical

management, laboratory results reporting, inventory

management, medical equipment management and

so on. This original weakness turned out to be a

blessing, as it largely obviated the pain of needing to

integrate multiple legacy IT systems from different

provider organisations, as often encountered

overseas when trying to unify data definitions and

functionalities, etc. for territory-wide connectivity.

The HA also chose to mostly build rather than

buy IT systems to maximally fit its own needs and

circumstances.

Eventually, the HA embarked on a most

comprehensive Clinical Management System to

support the work of clinicians and enhance service quality and patient safety. The system became

internationally acclaimed in the field of medical

informatics, and indeed pride of the organisation.

It was clinician-driven from the start, tailored to

the clinical workflow, and incorporated advanced

features to help doctors and nurses in decision

making such as drug allergy and dosage alerts,

knowledge support for evidence-based medicine,

and so on.17

Patient and community relations

The HA launched the Patients’ Charter that explicitly

listed patients’ rights and responsibilities, with

extensive staff communication to change the former

‘we (doctor/nurse) know best’ attitude. Patient

feedback on service quality and staff performance

was systematically collected. Full-time Patient

Relations Officers were employed in hospitals to deal

with complaints and suggestions. Patient Resource

Centres were set up in hospitals, while an HA

InfoWorld was eventually established in the new HA

Building to provide a health promotion and patient

education platform for the public.

As mentioned above, the Public Complaints

Committee incorporating members of the

community provided an independent platform

for appeals. Partnership with the community was

enshrined through the appointment of external

members, including patient advocacy organisations,

to different levels of governance, a far cry from the

closed system of the past.

Financing the reform

After adjusting for the resources required to uplift the

terms of employment of Schedule 2 hospitals’ staff to

be comparable to that of Schedule 1 hospitals, the

baseline recurrent budget of the HA for maintaining

the same level, scope and volume of services at the

beginning of financial year 1992/93 was agreed

to be HK$10 301 million.18 There were additional

upfront allocations that represented a true increase

in investment in the HA to kick-start the reform,

including HK$198 million for new projects,19 HK$98

million for new management initiatives,20 HK$90

million for capital projects, and HK$70 million for

IT projects.18

Quantifiable results

Significant improvements in system capacity and

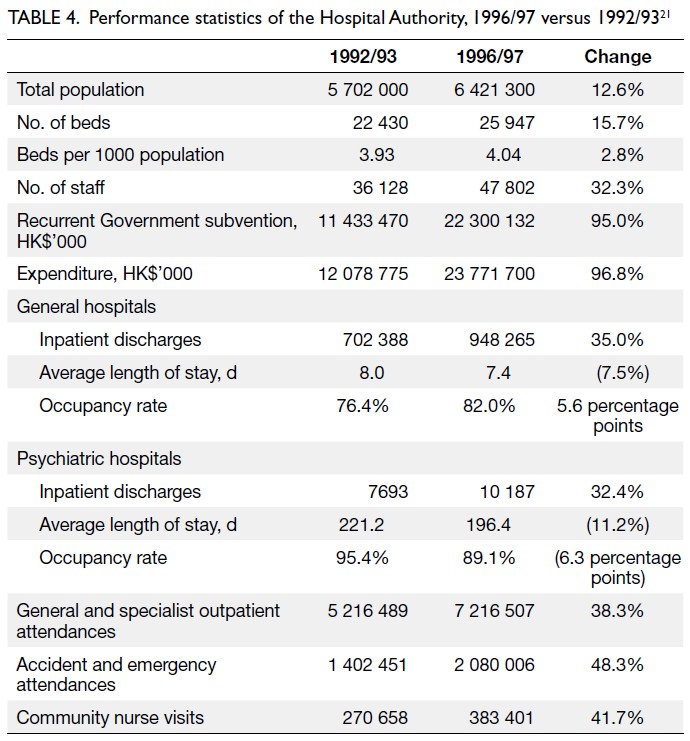

efficiency in the HA, underpinned by substantial

Government investment, can be seen in Table 4 which compares the full-year effect after the HA’s

takeover of management with that 5 years later.21

A number of observations can be made:

- The number of hospital beds increased more than population growth (15.7% vs 12.6%), improving the number of beds per 1000 population.

- Growth in inpatient discharges (35.0% general and 32.4% psychiatric) greatly exceeded growth in total bed numbers (15.7%), indicating more active patient management, as also reflected by shortened average lengths of stay for both general (by 7.5%) and psychiatric (by 11.2%) hospitals.

- The overall occupancy rate improved for general hospitals (from 76.4% to 82.0%), following better utilisation of beds in Schedule 2 hospitals and convalescent hospitals.

- Severe overcrowding in psychiatric hospitals was reduced (from 95.4% to 89.1% occupancy).

- An increase in staff productivity is evidenced by the increase in activities (35.0% for general inpatients, 32.4% for psychiatric inpatients, 38.3% for out-patients, 48.3% for accident and emergency attendances, and 41.7% for community nurse visits) exceeding the increase in staff numbers (32.3%). This does not yet reflect the immense improvements in service quality.

- Taking inflation into account,22 the increase in Government funding to the HA (real growth around 57.8%) and growth in expenditure (real growth around 59.2%) exceeded the increase in staff numbers and activities. As staff costs constituted more than 75% of total expenditure, this mainly reflected the creation of senior posts and general improvement in remuneration.

Analysis

The HA reform represented a bold social experiment

of unprecedented scale in Hong Kong’s history,

given that the HA became the second largest

employer, after the Civil Service, upon its takeover

of all Government and subvented hospitals in

one go. The direction of reform followed the then

prevalent international trend of new managerialism

and corporatisation to free the entity from rigidities

and confines of the Civil Service, and went much

further than the earlier Housing Authority reform.23

It coincided with a period of economic prosperity

during which the Government could afford investing

heavily in upgrading staff terms, funding new

management initiatives, hospital infrastructure,

computerisation, service improvements, and staff

training and development.

While Part 1 of this series describes the success

story of setting up the new HA,1 the management

takeover was when ‘the rubber hits the road’ that

could make or break any well-intentioned reform. Led

by a visionary Board with high-calibre experts from

various fields, the Authority took a pragmatic path

by selecting leaders for major executive positions

from among influential clinicians within the system

with a track record of being reformists who were

passionate to change the dysfunctional system of the

past.24 The atmosphere was nothing short of a brave

new world where the energy of doctors, nurses, allied

health staff and administrators was unleashed to

learn modern management concepts and methods,

and apply them to better the service. This was,

needless to say, highly appreciated by the public, to

the extent that the private sector felt threatened by

a loss of competitiveness in attracting both patients

and talented staff.25

While immense success was justified to

describe this early period, new issues also emerged.

The abolition of the previous Regional Offices

level and the emphasis on individual hospital’s

autonomy aimed to free up local initiatives and

promote internal competition to improve quality

and efficiency. However, this also led to reduced

cooperation and, arguably, an over-proliferation

of management positions (even small hospitals

were supposed to have their own HCEs and a full

complement of managers). This also meant that the

CE had dozens of direct reports, including HCEs

and Head Office deputies. As the system evolved, the

concept of hospital clustering became increasingly

emphasised to streamline management, initially by

function and eventually through formal structure.

At the hospital level, it remains uncertain to what

extent the inverted pyramid model and participative

management was fully embraced, depending on

the style and preferences of the rather autonomous

HCEs. Nevertheless, these were merely minor

issues for any major reforms of this complexity, and paled in significance compared to the overall

achievement.

As in all such reforms involving tens of

thousands of staff, managing the transition was

critical. From a historical perspective, the bridging-over

arrangement and the new HA terms represented

a major victory for staff coupled with the clever

design plus political clout of the then HA Board in

obtaining extra resources. Such a generous offer had

apparently not been repeated since for any other

corporatisation exercise of Government functions.

On the other hand, the retained linkage to the

Civil Service pay scales and salary point systems also

imposed limitation in flexibility when responding to

changing circumstances. When the economy turned

south and particularly after the Asian Economic

Crisis in 1998 when the HA faced budget cuts from

the Government, continued hiring on the original

terms to cope with the ever-increasing service

demand became increasingly untenable. The HA had

no choice but to repeatedly create new ranks with

less favourable packages, to circumvent the rank-to-rank

comparability with the Civil Service, much to

the dismay of new hires. The old culture of the ‘iron

rice bowl’ expecting job stability and annual salary

increments also persisted.

Be that as it may, the experience of turning

such a comprehensive reform blueprint into reality

with success for such an enormous public system,

rendered the HA internationally famous, especially

in the healthcare management circles. This was

achieved not by simply copying other models, but

by integrating best practices from multiple fields

and adapting them to the local situation to address

Hong Kong’s unique circumstances. An important

factor worth mentioning was the cross-disciplinary

learning that happened during that period. There

were intense interactions among Board members,

each with distinct expertise in their own fields,

with the senior executives. Conversely, Board

members also came to better understand the public

healthcare system and its contextual issues. Among

the senior executives, there were also vibrant mutual

learning between those with clinical and non-clinical

disciplines (in management, finance, IT, legal,

engineering, etc.) which provided synergistic results.26

Epilogue

Once the newborn organisation was firmly on its feet

with a new set of management structure, processes

and systems in place, a new phase of reform outgrew

the original blueprint. As the appointed senior

executives including the CE were predominantly

clinician-managers, the subsequent trajectory was

heavily influenced by the clinical and public health

perspectives, rather than simply system efficiency

and customer-focus concerns. The next article (Part

3) describes the emergent philosophy and practice of deepening reform within the HA in the subsequent years.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank the Hospital Authority for

permission to use the historical photo of its founding members

in this article, as scanned from its Annual Report 1990-1991.

Declaration

The author declares full responsibility for the accuracy of the

content, which does not represent the views of the Hospital

Authority. Given the scale of the reform, not all aspects can

be covered in detail. Interested readers and scholars are

encouraged to consult the Hospital Authority’s publications

for further information.

Notes

1. Ho W. The Hong Kong Hospital Authority reform: a historical perspective. Part 1: From pre–Hospital Authority era to establishment of the Hospital Authority. Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:508-14.

2. Coopers & Lybrand WD Scott. The Delivery of Medical Services in Hospitals—A Report for the Hong Kong Government. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer; December 1985.

3. Chung SY. Provisional Hospital Authority Report. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer; December 1989.

4. Also refer Chung SY, The Hospital Authority of Hong Kong–Part I: From Inception to Reality and its Initial Success. The Medical and Dental Directory of Hong Kong, fifth edition, 1994.

5. Hospital Authority, Hospital Authority Annual Report 1990-1991, pp 5-6. This version of the mission statement was in use until 2009, when the HA Board considerably simplified it.

6. Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority Annual Report 1990-1991, Appendix 2.

7. This is quite different from the picture in the UK, United States or Australia where hospital chiefs are more often non-doctors.

8. Except for radiology and radiotherapy departments where the Department Manager (DM) would be a senior radiographer; pathology departments where the DM would be a senior laboratory technologist; and allied health departments where the DM would be from their own discipline.

9. This puts patient care at the clinical frontline into centre stage at the ‘top’, while the ‘top management team’ should assume a more supportive rather than directive function at the ‘bottom’.

10. The Scott Report proposed the equalisation of staff terms by aiming at a level between that of Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 hospitals, which was vehemently opposed by those working in the former. From the start, therefore, the new HA package was designed to benchmark that of the Civil Servants, which meant an up-front recurrent investment to bring up those working in Schedule 2 hospitals.

11. While all staff of a particular pay band in the Civil Service may be entitled to a host of benefits, not all of them were enjoying all benefits at the same time (eg, government quarters depending on availability), hence the snapshot approach for computing comparable cost.

12. While not explicitly stated, it was implied that retention of the basic salary scales also meant retention of the yearly salary increment practice. In addition, the annual salary adjustments in line with inflation also followed that of the Civil Service.

13. Linking of the Cash Allowance as a percentage of basic salary was under the assumption that in time, the Government would also increase benefits for Civil Servants together with salary increase. However, it turned out that Government was cutting back Civil Service housing benefits a few years down the road. Following a report of the Director of Audit in 1994 that alleged breaching of the comparability principle, the Cash Allowance for new hires was delinked from basic salary.

14. As it played out, the HA Provident Fund Scheme was among the best-performing retirement funds in Hong Kong, both in terms of its administration and investment returns, thanks to the expertise in the Trust Board as well as professionals employed to manage the scheme.

15. With time, the interest portion of mortgages would decrease as will the Home Loan Interest Subsidy Scheme subsidy amount, but the staff member would generally have had pay rise or even promotion, hence could better afford the mortgage. It also meant regenerating available fund to the Scheme to support new applications.

16. Staff unions successfully negotiated using the last drawn salary point as Civil Servant (value updated to the date of retirement from HA) for calculation in the Frozen Pension arrangement. Another option was the Mixed Service Pension arrangement where the staff would retain full pension eligibility for total years served including as HA staff, but receive a reduced Cash Allowance and would not be eligible for the HA Provident Fund. There was also negotiation on the accumulated leave days, resulting in agreement that each staff member was allowed to carry over a maximum of 30 days of ‘sinking leave’.

17. In contrast, many overseas systems are fragmented across hospitals and often structured on the business/financial side while weak on clinical side. The Clinical Management System eventually evolved to become the territory-wide Electronic Health Record (eHR) system that spans the private sector as well.

18. Hospital Authority, Hospital Authority Annual Report 1992-93, p 18. Since HA only took over operation on 1 December 1991, the budget for 1992/93 was the first full-year budget.

19. This amount was for commissioning and opening of new beds and facilities, which would have to be spent with or without the HA’s establishment.

20. Mainly the salaries of all new management positions in the Head Office and hospitals.

21. Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority Annual Reports 1992/93 and 1996/97, Appendices.

22. Inflation figures in Hong Kong were 8.8% (1993), 8.7% (1994), 9.1% (1995) and 6.3% (1996). International Financial Statistics database, International Monetary Fund. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG?locations=HK. Accessed 29 Dec 2025. This gives a cumulative inflation of around 37.2% for the period.

23. The Housing Department, which is the executive arm of the Hong Kong Housing Authority, remained within the Civil Service.

24. The first two CEs of HA, Dr EK Yeoh and the author, were active members of the former Government Doctors’ Association, as were Deputy Directors Dr WM Ko 高永文 and Dr Hong Fung 馮康. It is noteworthy that Dr Yeoh, Dr York Chow 周一嶽 (one among the first batch of HCEs) and Dr Ko later became the three successive policy secretaries in the Government (Secretary for Health and Welfare/Secretary for Food and Health) spanning the period 1999 to 2017.

25. The private hospitals began to get their acts together and formed the Hong Kong Private Hospitals Association (HKPHA) in 2000, as well as introduced the UK-based Trent Accreditation system in an effort to improve their own management and quality of service. The author became Chairman of HKPHA in 2018 and thus conversant with its history.

26. Such cross-disciplinary learning seemed to have lost momentum in recent times, as fewer clinicians promoted to management positions pursue formal management courses, while non-clinician executives entirely home-grown within the system may not be able to bring in fresh perspectives and expertise as in the formative years.