Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 2 Feb 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Utilisation trends and early outcomes of robotic

arm–assisted total hip arthroplasty in a tertiary

joint replacement centre in Hong Kong

KL Fong1; Amy Cheung, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery), FHKCOS2; Michelle Hilda Luk, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery), FHKCOS2; Thomas KC Leung, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery), FHKCOS2; Lawrence CM Lau, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery), FHKCOS2; PK Chan, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery), FHKCOS1; KY Chiu, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery), FHKCOS1; Henry Fu, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery), FHKCOS1

1 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof H Fu (drhfu@ortho.hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study evaluated utilisation

trends and early outcomes of robotic arm–assisted

primary total hip arthroplasty (rTHA) compared

with conventional THA (cTHA) in Hong Kong.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study included

all patients who underwent primary THA in public

hospitals under the Hong Kong West Cluster

(HKWC) from 2019 to 2024. Data were retrieved

from the Hospital Authority’s electronic databases.

The primary outcome was the percentage utilisation

of rTHA relative to cTHA. Secondary outcomes

included operating time (skin-to-skin), length of

stay (LOS), 30- and 90-day reoperation rates, and

30- and 90-day emergency department attendance.

Differences in these outcomes between rTHA and

cTHA were examined.

Results: In total, there were 311 and 242 cases of

rTHA and cTHA, respectively. Robotic utilisation

increased from 32.0% in 2019 to 62.2% in 2024.

Regarding patient outcomes, rTHA increased

operating time by 14.59 minutes (142.02 ± 53.88 vs

127.43 ± 53.34; P=0.002). There was no significant

difference in median LOS between the two groups.

Robotic surgery was also associated with a lower

30-day reoperation rate (0.32% vs 2.07%; P=0.049).

One reoperation due to dislocation was performed in the rTHA group. In the cTHA group, one

dislocation, two periprosthetic fractures, and two

infections required revision surgery.

Conclusion: Given the increasing use of rTHA in

the HKWC, the present findings suggest that rTHA

is associated with a lower 30-day reoperation rate.

As the first local study on early outcomes of rTHA,

these results may serve as reference data for other

centres.

New knowledge added by this study

- Utilisation of robotic arm–assisted primary total hip arthroplasty (rTHA) nearly doubled between 2019 and 2024.

- Robotic arm–assisted primary total hip arthroplasty was associated with a lower 30-day reoperation rate.

- Early results suggested that rTHA was associated with fewer postoperative complications requiring reoperation.

- Long-term data are needed to further evaluate trends in operating time and length of stay, and to determine how these outcomes translate into improved functional outcomes.

Introduction

In Hong Kong, robotic surgery has gained popularity

across various specialties, with the Da Vinci robot

becoming the standard of care in urology and seeing

widespread use in general surgery.1 Orthopaedic

robotic systems are often semi-active and partially

controlled by the surgeon.2 In total hip replacement,

an image-based, semi-active, haptic-constrained

robotic arm system is commonly used. The Mako Robotic Arm Assisted Surgical System (Stryker Corp,

Fort Lauderdale [FL], US) is a surgical system for total

hip replacement approved by the US Food and Drug

Administration.3 Surgical planning is performed

using three-dimensional computed tomography

scans, enabling accurate, patient-specific planning.

Bone removal is performed under haptic control

by the robotic arm, with component implantation

angles also guided by the robot, enhancing precision and accuracy.4 5 Western literature has shown that

robotic arm–assisted primary total hip arthroplasty

(rTHA) yields better radiological and clinical

outcomes.6 7 8 However, local data on the early clinical

outcomes of robotic total hip replacement remain

limited. Robotics was first introduced locally by

the Hong Kong West Cluster (HKWC) in 2019, and

its use has been increasing. Our cluster has since

accumulated substantial experience and moved

beyond the learning curve. This study aimed to

evaluate utilisation trends and patient outcomes of

rTHA compared with conventional THA (cTHA).

Methods

Objective

The primary outcome was the percentage utilisation

of rTHA relative to cTHA in the HKWC from 2019

to 2024. Secondary outcomes included operating

time (skin-to-skin), length of stay (LOS), 30-day

and 90-day reoperation, and 30-day and 90-day

emergency department attendance. Length of stay

was defined as the duration of inpatient admission

following THA. Discharge criteria included the

ability to ambulate with a walking aid and the absence

of impending medical conditions. Reoperation was

defined as undergoing another hip procedure, such

as revision or implant removal, within 30 or 90

days of surgery. Emergency department attendance was defined as presentation to the accident and

emergency department within 30 or 90 days

following discharge.

Additionally, postoperative complication

rates were examined in terms of reoperation,

emergency department attendance, and the

corresponding diagnoses. Complications of interest

included dislocation, periprosthetic fracture, and

periprosthetic joint infection. The study adhered

to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guideline.

Surgical technique

Total hip arthroplasty in both groups was performed

via a posterior approach with the patient in the left

lateral decubitus position. All patients received

a cementless, proximally coated femoral stem

(Accolade II; Stryker Corp, Mahwah [NJ], US) and a

porous acetabular shell (Trident Acetabular System;

Stryker Corp, Mahwah [NJ], US).3

In the cTHA group, the femoral osteotomy site

was marked based on a predetermined distance from

the lesser and greater trochanters. The acetabulum

was reamed freehand, down to the true floor and

healthy bleeding bone. Cup impaction was guided

by an alignment guide and intraoperative landmarks,

including the transverse acetabular ligament and the

anterior and posterior acetabular walls, to determine

the orientation of the acetabular component.9 10

All rTHAs were performed using the Mako

Robotic Arm Assisted Surgical System, which guided

acetabular reaming and component placement

within haptically confined boundaries. A trial cup

was inserted at the appropriate abduction angle,

with anteversion guided by the robotic arm.10

Study design and patient selection

This was a retrospective cohort study. Data were

retrieved from the Clinical Data Analysis and

Reporting System (CDARS) and the Clinical

Management System (CMS). The CDARS is a

database containing medical information for

research purposes, whereas the CMS is primarily

used for day-to-day clinical management. The

function to distinguish between rTHA and cTHA

was introduced in CDARS in 2021. Therefore, data

from 1 January 2021 to 31 December 2024 were

collected via CDARS, while data from 2019 to 2020

were obtained through CMS chart review. Both

systems follow standardised data protocols and can

be used concurrently.

All patients who underwent primary unilateral

rTHA or cTHA in the HKWC were included.

Diagnoses included osteoarthritis, avascular

necrosis, aseptic necrosis, developmental dysplasia

of the hip, dislocation, and fractures. Patients with

diagnoses of bone malignancy, chronic osteomyelitis,

or complex primary THA—such as Crowe type III/IV hip dysplasia or post-traumatic osteoarthritis with retained hardware—were excluded. Patients

who had staged bilateral procedures were included

as separate cases. During the initial learning phase

in 2019, all surgeries were performed by a single

surgeon (corresponding author). From 2020 onwards, other surgeons

within the division began performing rTHA.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS (Windows

version 29.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). A two-tailed

significance threshold was set at P<0.05. The

normality of continuous variables was assessed

using skewness and kurtosis, as well as the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Normally

distributed continuous variables, such as operating

time, were compared using independent samples

t tests. The non–parametric continuous variable,

LOS, was analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Categorical data were compared via the Chi squared

test.

Results

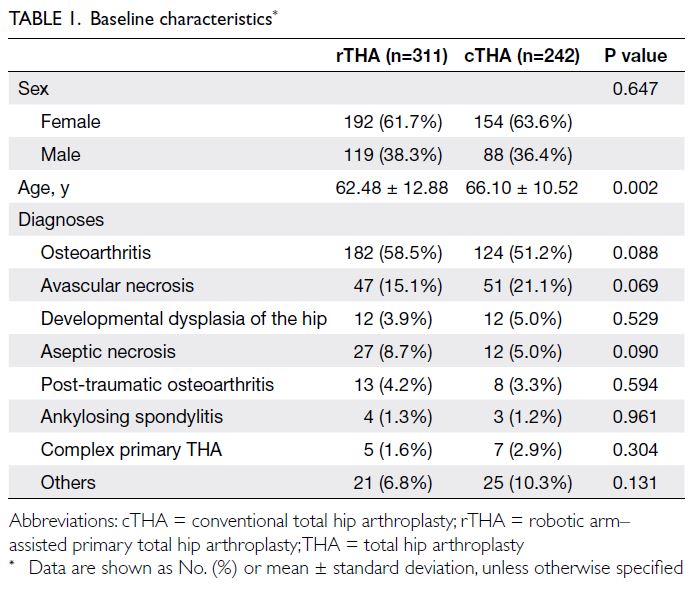

From 2019 to 2024, a total of 311 and 242 THAs

were performed in the rTHA and cTHA groups,

respectively. Patient demographics are summarised

in Table 1. In terms of sex distribution, 61.7% of

patients in the rTHA group and 63.6% of those in

the cTHA group were women. Patients undergoing

rTHA had a lower mean age at the time of surgery

compared with those receiving cTHA (62.48 ± 12.88 vs 66.10 ± 10.52 years; P=0.002). There was

a tendency for rTHA to be performed in younger

patients, although the distribution of diagnostic

categories was similar between groups.

Osteoarthritis was the most common diagnosis

in both groups, accounting for 58.5% of rTHA cases

and 51.2% of cTHA cases. The second most common

diagnosis was avascular necrosis, representing 15.1%

of rTHA cases and 21.1% of cTHA cases (Table 1).

Utilisation trends

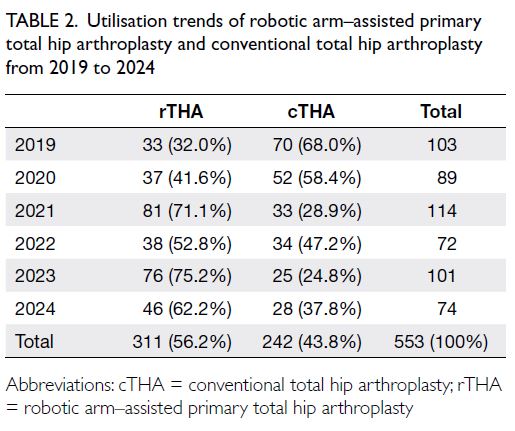

The primary outcome was the utilisation rate

of rTHA in the HKWC. As shown in Table 2, a

steady increase in robotic cases was observed,

from 32.0% in 2019 to 62.2% in 2024. Notably, the

highest proportion was recorded in 2023, at 75.2%.

In contrast, the proportion of conventional cases

steadily declined, almost halving from 68.0% in 2019

to 37.8% in 2024. The substantial increase in rTHA

proportion illustrates a clear shift from cTHA to

rTHA as the predominant surgical approach over

the study period.

Table 2. Utilisation trends of robotic arm–assisted primary total hip arthroplasty and conventional total hip arthroplasty from 2019 to 2024

Operating time (skin-to-skin)

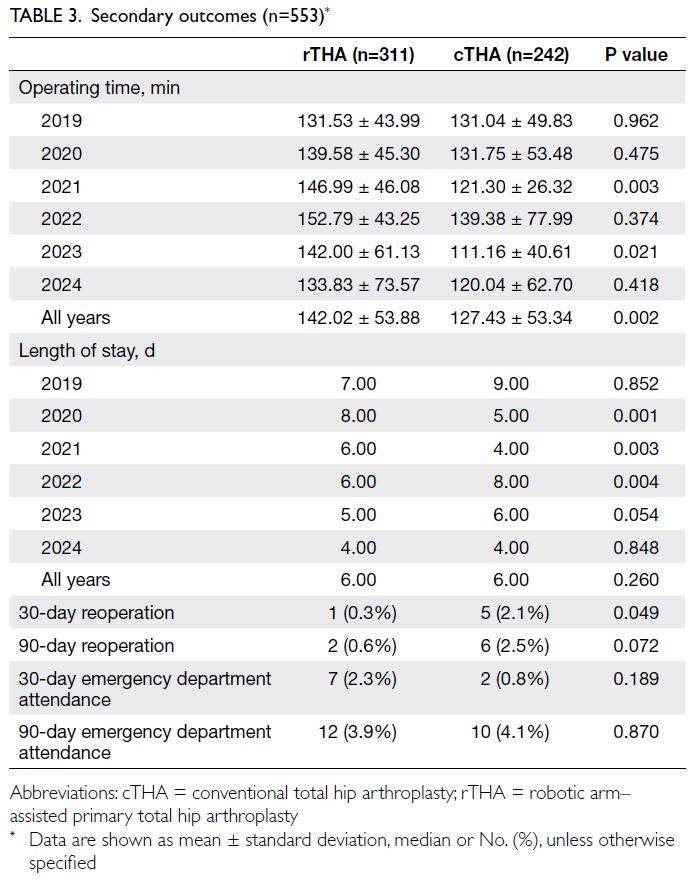

The secondary outcomes are presented in Table 3.

Robotic arm–assisted primary total hip arthroplasty had a mean operating time of 142.02 minutes, which was 14.59 minutes longer than that

of cTHA (127.43 minutes). For rTHA, the mean

operating time was 131.53 minutes in 2019, increased

to 139.58 minutes in 2020 with more surgeons

beginning their learning curve, and then reached a

plateau over the next 2 years (2021: 146.99 minutes;

2022: 152.79 minutes). In the final 2 years of the

study, operating time decreased to 142.00 minutes in

2023 and 133.83 minutes in 2024, reflecting passing

of learning curve by the whole surgical team. In

contrast, cTHA operating times ranged from 111

to 139 minutes, without a clear trend. In the first

2 years, operating times were similar (2019: 131.04

minutes; 2020: 131.75 minutes), followed by a slight

increase to 139.38 minutes in 2022, then dropped to

111.16 minutes in 2023, with a moderate increase to

120.04 minutes in 2024.

Length of stay

Discharge criteria remained consistent throughout

the study period and included the ability to ambulate

independently with a walking aid, effective pain

control, absence of immediate wound complications,

and no major medical issues. Most patients were

discharged directly under the enhanced recovery

after surgery protocol; only those undergoing

complex primary THA (<10% of the cohort) were

transferred to rehabilitation hospitals. The median

LOS was the same in both groups (6.00 vs 6.00 days;

P=0.260) [Table 3]. When rTHA was first introduced

in 2019, all procedures were performed by a single

surgeon, which may have influenced early outcomes.

In 2020 and 2021, more surgeons began performing

rTHA, which may partly explain the longer LOS

observed during this learning-curve period.

Reoperation and emergency department

attendance

Robotic arm–assisted primary total hip arthroplasty

was associated with a lower 30-day reoperation rate compared with cTHA (0.32% vs 2.07%; P=0.049).

Similarly, a trend towards a lower 90-day reoperation

rate was observed for rTHA (0.64% vs 2.48%;

P=0.072) [Table 3].

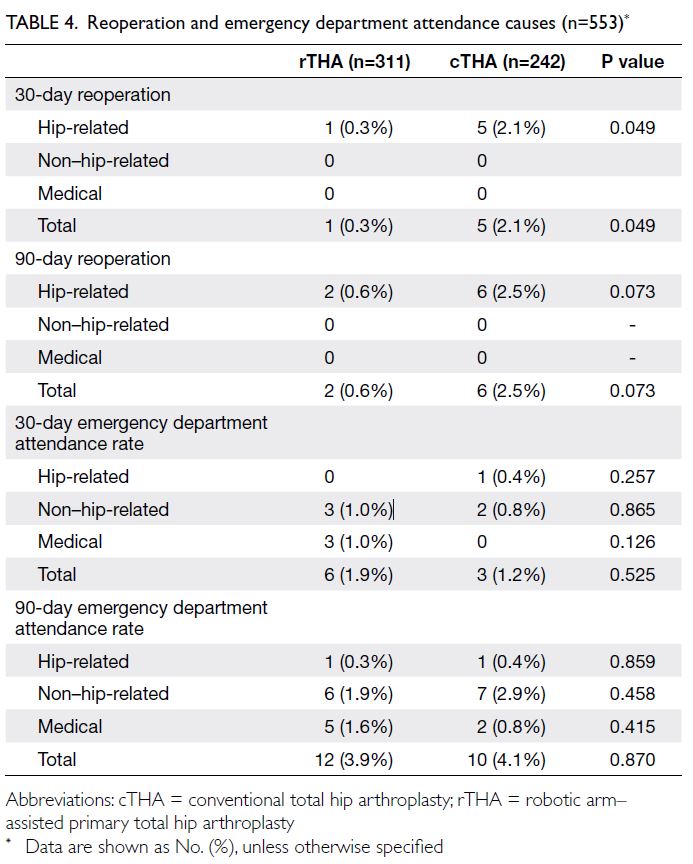

All 30-day reoperations were hip-related. As

shown in Table 4, one reoperation was performed

in the rTHA group and five in the cTHA group.

In the rTHA group, reoperation was required for

a hip dislocation, which was managed by closed

reduction. In the cTHA group, two periprosthetic

fractures of the proximal femur were treated with

open reduction and internal fixation. Two additional

reoperations were performed for wound infections,

and one hip dislocation was managed by closed

reduction.

All 90-day reoperations were also hip-related.

In the rTHA group, one additional case of dislocation

was noted. In the cTHA group, one new case of

periprosthetic fracture was identified (Table 4).

Discussion

The number of THAs utilising robotic assistance

increased over the study period. The proportion of

robotic cases relative to cTHA also rose, with rTHA

accounting for 56.2% of all THAs when all years

were combined. These findings indicate a shift in the

primary surgical approach within the HKWC from

conventional to robotic techniques. At present, four

public hospitals in Hong Kong have acquired robotic

systems, with several additional systems available on

loan. Brinkman et al11 reported that public interest

in rTHA substantially increased between 2011

and 2020. Compared with online search volumes

for conventional arthroplasty, this growth was

statistically significant.

Clement et al12 reported that, despite the higher

costs associated with robotics, rTHA was a cost-effective

intervention compared with cTHA owing

to greater gains in health-related quality of life, as

measured by the EuroQol 5-Dimension. In addition,

the rising popularity of rTHA may be attributed to

its favourable clinical, functional, and radiological

outcomes, which are discussed further below.

Robotic THA was associated with an increase

in operating time of approximately 15 minutes, which

is slightly less than the 20-minute increase reported

by Han et al (20.72 minutes; P=0.002).13 This

difference may be attributable to the need for system

registration or placement of positioning pins, as well

as the effects of the learning curve. When rTHA

was first introduced in Hong Kong in 2019, only

one experienced surgeon was using the procedure,

with an average operating time of 131 minutes. As

more surgeons began using the robotic system, a

learning-curve effect was suggested by an increase

in operating time over the next 3 years (139.6, 147.0,

and 152.8 minutes, respectively). Notably, robotic

operating time then decreased by 11 minutes from 2022 to 2023, and by a further 8 minutes to 133.83

minutes, suggesting increased familiarity with the

system and the possible completion of the learning

curve. Kayani et al14 similarly reported that robot-assisted

acetabular cup positioning during THA was

associated with a learning curve of 12 cases.

There were no statistically significant

differences in LOS between the rTHA and cTHA

groups; both had a median LOS of 6.00 days. In a

retrospective study, Remily et al15 matched patients

in a 1:1 ratio between robotic and conventional

groups (4630 patients per group) and reported

a significantly shorter mean LOS in the rTHA

group (3.4 vs 3.7 days; P=0.001). These findings

may reflect the ability of robotic technology to

execute preoperative plans tailored to each patient’s

unique anatomy. The results may also be related to

reduced iatrogenic trauma and faster postoperative

rehabilitation. Similarly, Heng et al16 found that the

mean LOS in the robotic group was approximately

1 day shorter. Nevertheless, differences in data

distribution and reporting methods should be noted.

While previous authors reported mean LOS, we

reported the median LOS due to the non-parametric

distribution of our data.

Social and cultural factors may also influence

LOS. Western patients often have access to more

spacious home environments, whereas patients

in Hong Kong may reside in more confined living

spaces, potentially reducing their willingness or

readiness for early discharge. Furthermore, patients

and their families in Hong Kong often adopt a more

conservative approach to discharge, preferring

extended care under medical supervision and a self-perceived

burden to their family members if they

return home early.17 These factors may contribute to

a prolonged LOS.

It was evident that rTHA was associated

with a lower 30-day reoperation rate, with a trend

towards a lower 90-day reoperation rate. Our

findings are consistent with those of Shaw et al18

who reported significantly lower dislocation rates

with rTHA compared with cTHA (0.6% vs 2.5%;

P<0.046). Notably, all cases of unstable rTHA were

successfully managed conservatively in the absence

of component malposition, whereas 46% of unstable

cTHA cases required revision surgery for recurrent

instability due to malalignment.18 A previous

postoperative analysis in Hong Kong19 showed that

96% of robotically positioned acetabular cups fell

within the Lewinnek safe zone (inclination 30°-50°,

anteversion 5°-25°).

Although rTHA improves the accuracy

of implant positioning and reduces outliers in

acetabular cup placement,20 21 there remains a lack

of data concerning how these improved radiological

outcomes translate into differences in long-term

clinical recovery, functional outcomes, implant survivorship, and complication rates when compared with cTHA.22

Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first territory-wide

study in Asia comparing cTHA and rTHA. However,

several limitations should be acknowledged. First,

the use of big data analysis through the CDARS

precluded adjustment for certain confounding

factors, such as surgeon- and hospital-related

variables. Second, the dataset was confined to the

HKWC as ethics approval could not be obtained

for multi-cluster or private hospital data. Although

other public-sector clusters are also managed by

the Hospital Authority, caution should be exercised

when comparing our findings to other settings.

Nevertheless, the inclusion of multiple surgeons

reflects real-world clinical practice. Finally,

functional outcomes and patient-reported outcome

measures were not assessed; as such, the impact of

rTHA from the patient’s perspective could not be

evaluated.

Evaluation of longer-term outcomes and

registry data from additional clusters will be essential to develop optimal THA strategies, those that

achieve key technical objectives, enhance patient

outcomes, and reduce complications.

Conclusion

The use of rTHA nearly doubled between 2019

and 2024 and was associated with a lower 30-day

reoperation rate compared with cTHA. However, as

this study focused solely on early patient outcomes,

further research is warranted to determine whether

these findings translate into improved long-term

functional outcomes.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KL Fong, H Fu.

Acquisition of data: KL Fong, H Fu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KL Fong, H Fu.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: KL Fong, H Fu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KL Fong, H Fu.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

The results of this study were presented as an oral presentation

at the 44th Annual Congress of Hong Kong Orthopaedic

Association, Hong Kong, 2-3 November 2024.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board

of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong

Kong West Cluster, Hong Kong (Ref No.: UW 24-128). The

requirement for informed patient consent was waived by the

Board due to the retrospective nature of the study.

References

1. Ng AT, Tam PC. Current status of robot-assisted surgery.

Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:241-50. Crossref

2. Smith A, Picheca L, Mahood Q. Robotic Surgical Systems

for Orthopedics. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs

and Technologies in Health; 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK602663/. Accessed 12

Mar 2025.

3. Stryker. Available from: https://www.stryker.com. Accessed 12 Mar 2025.

4. Inabathula A, Semerdzhiev DI, Srinivasan A, Amirouche F,

Puri L, Piponov H. Robots on the stage: a snapshot of the

American robotic total knee arthroplasty market. JB JS

Open Access 2024;9:e24.00063. Crossref

5. Jahng KH, Kamara E, Hepinstall MS. Haptic robotics in total hip arthroplasty. In: Minim Invasive Surg

Orthopaedics. New York: Springer; 2015: 1-15. Crossref

6. Salášek M, Pavelka T, Rezek J, et al. Mid-term functional

and radiological outcomes after total hip replacement

performed for complications of acetabular fractures. Injury

2023;54:110916. Crossref

7. De Santis V, Bonfiglio N, Basilico M, et al. Clinical and

radiographic outcomes after total hip arthroplasty with the

NANOS neck preserving hip stem: a 10 to 16-year followup

study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;22(Suppl

2):1061. Crossref

8. Perets I, Walsh JP, Close MR, Mu BH, Yuen LC, Domb BG.

Robot-assisted total hip arthroplasty: clinical outcomes

and complication rate. Int J Med Robot 2018;14:e1912. Crossref

9. Fontalis A, Kayani B, Plastow R, et al. A prospective

randomized controlled trial comparing CT-based planning

with conventional total hip arthroplasty versus robotic

arm-assisted total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2024;106-B:324-35. Crossref

10. Domb BG, El Bitar YF, Sadik AY, Stake CE, Botser IB.

Comparison of robotic-assisted and conventional

acetabular cup placement in THA: a matched-pair

controlled study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:329-36. Crossref

11. Brinkman JC, Christopher ZK, Moore ML, Pollock JR,

Haglin JM, Bingham JS. Patient interest in robotic total

joint arthroplasty is exponential: a 10-year Google trends

analysis. Arthroplast Today 2022;15:13-8. Crossref

12. Clement ND, Gaston P, Hamilton DF, et al. A cost-utility

analysis of robotic arm-assisted total hip arthroplasty:

using robotic data from the private sector and manual

data from the National Health Service. Adv Orthop

2022:2022:5962260. Crossref

13. Han PF, Chen CL, Zhang ZL, et al. Robotics-assisted versus

conventional manual approaches for total hip arthroplasty:

a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative

studies. Int J Med Robot 2019;15:e1990. Crossref

14. Kayani B, Konan S, Huq SS, Ibrahim MS, Ayuob A, Haddad

FS. The learning curve of robotic-arm assisted acetabular

cup positioning during total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int

2021;31:311-9. Crossref

15. Remily EA, Nabet A, Sax OC, Douglas SJ, Pervaiz SS,

Delanois RE. Impact of robotic assisted surgery on

outcomes in total hip arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today

2021;9:46-9. Crossref

16. Heng YY, Gunaratne R, Ironside C, Taheri A. Conventional

vs robotic arm assisted total hip arthroplasty (THA) surgical

time, transfusion rates, length of stay, complications and

learning curve. J Arthritis 2018;7:1000272. Crossref

17. Bayer-Oglesby L, Zumbrunn A, Bachmann N; SIHOS

Team. Social inequalities, length of hospital stay for

chronic conditions and the mediating role of comorbidity

and discharge destination: a multilevel analysis of hospital

administrative data linked to the population census in

Switzerland. PLoS One 2022;17:e0272265. Crossref

18. Shaw JH, Rahman TM, Wesemann LD, Jiang CZ,

G Lindsay-Rivera K, Davis JJ. Comparison of postoperative

instability and acetabular cup positioning in robotic-assisted

versus traditional total hip arthroplasty. J

Arthroplasty 2022;37(8S):S881-9. Crossref

19. Fu CH, Cheung YL, Cheung MH, et al. Robotic arm-assisted

total hip replacement: early experience in Hong

Kong. In: Proceedings of the 40th Annual Congress of the

Hong Kong Orthopaedic Association; 2020 Oct 31-Nov 1; Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Academy of

Medicine Press; 2020: 71. Available from: https://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/305989. Accessed 12 Mar 2025.

20. Beverland DE, O’Neill CK, Rutherford M, Molloy D,

Hill JC. Placement of the acetabular component. Bone

Joint J 2016;98-B(1 Suppl A):37-43. Crossref

21. Kayani B, Konan S, Thakrar RR, Huq SS, Haddad FS.

Assuring the long-term total joint arthroplasty: a triad of

variables. Bone Joint J 2019;101-B(1_Supple_A):11-8. Crossref

22. Kayani B, Konan S, Ayuob A, Ayyad S, Haddad FS. The

current role of robotics in total hip arthroplasty. EFORT

Open Rev 2019;4:618-25. Crossref