Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 30 Jan 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

A ten-year evaluation of the incidence of

obstetric anal sphincter injury with a reduced episiotomy rate

YY Lau, MB, ChB, MRCOG; TW Chau, MB, ChB; WC Tang, MB, BS; Rachel YK Cheung, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); SM Ng, MSc; TM Tso, MSc, BN; Symphorosa SC Chan, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr YY Lau (yanyanlau@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The role of episiotomy in preventing

obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) remains

controversial. Liberal use of episiotomy has been

reduced locally. This study aimed to review the

incidence of OASIS in our unit over the past decade

given the reduced episiotomy rate.

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted in a

single tertiary obstetrics and gynaecology unit. All

singleton vaginal deliveries, including normal and

instrumental deliveries, between 2012 and 2021

were included. Data were retrieved from the hospital

electronic delivery database between July 2022 and

June 2023. The degree of OASIS was assessed using

the Abdul Sultan classification.

Results: In total, 43 732 deliveries were included.

The episiotomy rate decreased from 62.8% in 2012

to 44.7% in 2021 (P<0.001), while the OASIS rate

increased from 0.3% to 1.4% over the same period

(P<0.001). Among nulliparous women, the OASIS

rate was significantly lower with episiotomy in both

normal vaginal deliveries (0.6% vs 1.7%; P<0.001) and

instrumental deliveries with episiotomy than without

(1.7% vs 42.9%; P<0.001). Among multiparous

women, the OASIS rate was significantly lower in

normal vaginal delivery without episiotomy than with (0.3% vs 0.5%; P=0.026), but significantly lower

in instrumental deliveries with episiotomy than

without (0.5% vs 23.5% P<0.001). Overall, episiotomy

was a protective factor for OASIS (odds ratio=0.273,

95% confidence interval= 0.208-0.358; P<0.001).

Conclusion: Episiotomy was protective against

OASIS among nulliparous women with singleton

normal vaginal delivery and instrumental delivery

in an Asian population. It also conferred protection

among multiparous women undergoing instrumental

delivery but not in those having normal vaginal

delivery.

New knowledge added by this study

- Episiotomy is a protective factor against obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) among nulliparous women undergoing singleton normal vaginal delivery and instrumental delivery in an Asian population.

- Episiotomy also confers protection against OASIS among multiparous women undergoing instrumental delivery in an Asian population.

- Conversely, episiotomy may increase the risk of OASIS in multiparous women undergoing normal vaginal delivery.

- It is recommended that women should be informed of these findings to support informed decision-making regarding episiotomy.

- A more restrictive approach should be adopted in multiparous women undergoing normal vaginal delivery.

Introduction

Obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) is a serious

complication of vaginal delivery that can result in

faecal incontinence, thereby impairing women’s

quality of life. Reported prevalence rates of OASIS

range from less than 1% to 11%.1 2 3 In the United

Kingdom, the incidence tripled from 1.8% to 5.9%

between 2000 and 2012, presumably due to improved detection techniques and increased awareness.4 In

Hong Kong, the incidence increased from 0.04% in

2004 to 0.1% in 2009, and to 0.3% in 2014 during

normal vaginal deliveries.5 Episiotomy, commonly

performed during the second stage of labour to

facilitate delivery and prevent excessive stretching

of the perineal muscles, may increase intrapartum

blood loss and perineal pain.6 The role of episiotomy in mitigating OASIS remains controversial.7 8

Consequently, the liberal use of episiotomy has

declined in Hong Kong, with rates falling from 81%

in 2004 to 66.2% in 2009 and 47.4% in 2014.5 Ethnic

differences in pelvic floor biometry and pelvic organ

mobility have been reported,8 9 and studies suggest

that Asian women are more prone to OASIS.10 11 This

study aimed to review the incidence of OASIS in our

unit over the past decade in the context of declining

episiotomy rates.

Methods

This study was conducted in Prince of Wales

Hospital, a tertiary obstetrics and gynaecology unit

with an annual delivery volume of approximately

4500 to 6000. All singleton vaginal deliveries—including spontaneous vaginal, ventouse, or

forceps deliveries—between 1 January 2012 and 31

December 2021 were included. Breech and preterm

deliveries were excluded. Maternal demographics

were entered into the electronic record either

antenatally by midwives or obstetricians if women

had received antenatal care in our unit, or by

midwives immediately after delivery. Maternal

age and body mass index (BMI) were recorded at

delivery. Macrosomia was defined as a birth weight

of ≥4000 g. Most spontaneous vaginal deliveries

were conducted by trained midwives or student

midwives under supervision; instrumental deliveries

were performed by trained obstetricians or trainees

under senior supervision. When indicated, a left

mediolateral episiotomy and a hands-on approach

to protect the perineum were used by both midwives

and doctors. Per vaginal and per rectal examinations

were performed immediately after delivery. If

OASIS was suspected, assessment was conducted

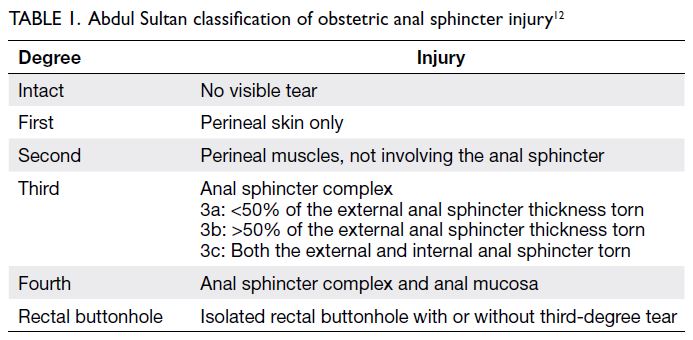

by an obstetric specialist. The degree of OASIS

was classified using the Abdul Sultan classification

(Table 1).12 Delivery details were documented by

midwives immediately after birth. Operative records

for instrumental deliveries and OASIS repair, where

applicable, were completed immediately after the

procedure. Data were extracted from the hospital’s

electronic delivery database between July 2022 and

June 2023. Statistical analyses were performed using

SPSS (Windows version 29.0; IBM Corp, Armonk

[NY], United States). Descriptive analyses were used

to examine demographics, mode of delivery, and the

prevalences of episiotomy and OASIS. Means were

compared between groups using the independent

samples t test. Frequencies were compared using

the Pearson Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test,

as appropriate. Trends were analysed using the Chi

squared test for trend (Cochran–Armitage test). All

risk factors were included in multivariable logistic

regression analysis except epidural analgesia,

nulliparity, and neonatal birth weight (justification

provided in Results section). A P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 43 732 deliveries were included in this

study. The mean ± standard deviation maternal

age at delivery was 31.5 ± 4.7 years and the median

parity was 0 (interquartile range, 1). Of these, 22 566

(51.6%) were nulliparous and 21 166 (48.4%) were

multiparous. Among the latter, 2268 (10.7%) had

only previously delivered by Caesarean section and were therefore vaginally nulliparous. Data

concerning previous delivery mode were missing

for 905 women (4.3%). In total, 39 603 women

(90.6%) had a normal vaginal delivery, 3528 (8.1%)

had ventouse delivery, and 601 (1.4%) had a forceps

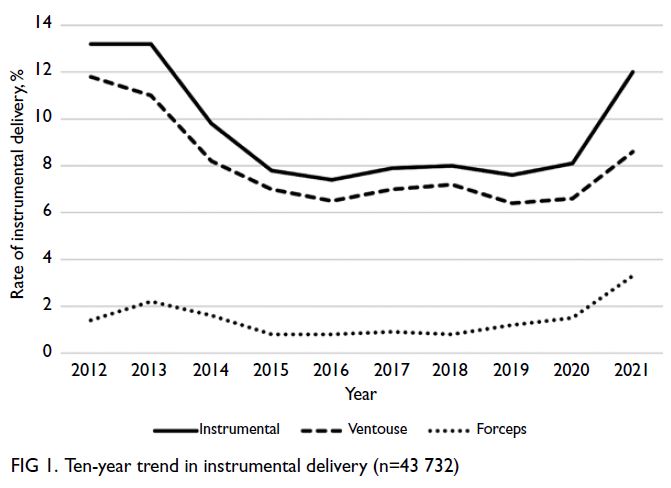

delivery. Over the 10-year period from 2012 to 2021,

the overall instrumental delivery rate and ventouse

delivery rate declined significantly, from 13.2% to

12.0% (P<0.001) and from 11.8% to 8.6%, respectively

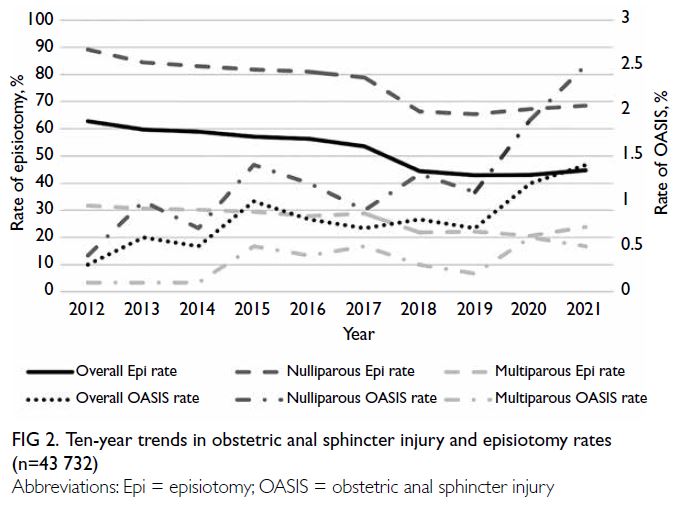

(P<0.001) [Fig 1]. Overall, 23 325 women (53.3%)

underwent episiotomy, whereas 20 407 (46.7%) did

not; 326 women (0.7%) sustained OASIS, whereas

43 406 (99.3%) did not. The overall episiotomy rate

decreased from 62.8% to 44.7% (P<0.001), with

reductions observed in both nulliparous (from 89.2%

to 68.5%; P<0.001) and multiparous women (from

31.7% to 23.8%; P<0.001). Conversely, the overall

OASIS rate increased from 0.3% to 1.4% (P<0.001),

with higher rates in nulliparous (from 0.4% to 2.5%;

P<0.001) and multiparous women (0.1%-0.5%;

P<0.001) [Fig 2].

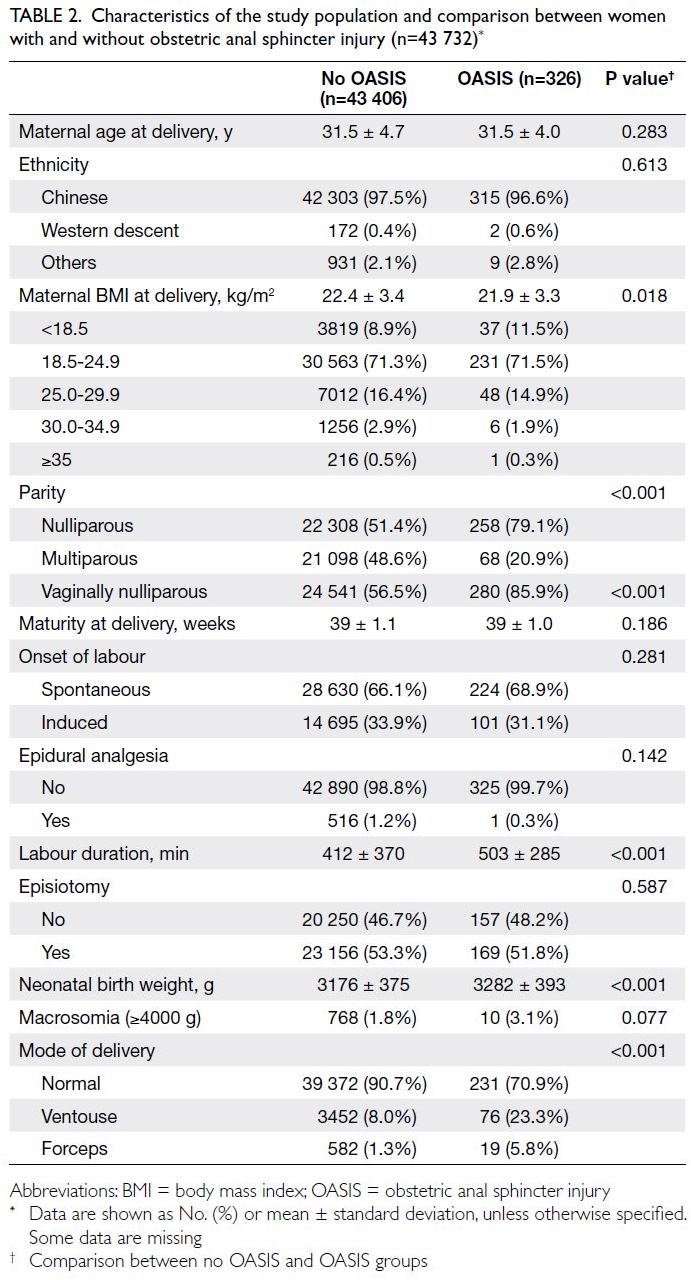

The characteristics of the study population

are summarised in Table 2. Episiotomy rates among

women with and without OASIS were 51.8% and

53.3%, respectively (P=0.587). A higher proportion

of women in the OASIS group were nulliparous

(79.1% vs 51.4%; P<0.001) and vaginally nulliparous

(85.9% vs 56.5%; P<0.001). Instrumental delivery

was also more common in the OASIS group

compared with the non-OASIS group (29.1% vs

9.3%; P<0.001). No statistically significant difference

was observed between the type of instrumental

vaginal delivery and the occurrence of OASIS

(P=0.128). Women with OASIS had a lower BMI,

a longer duration of labour, and delivered heavier

neonates. No significant differences were observed

in mean maternal age, ethnicity, gestational age,

onset of labour, epidural analgesia, episiotomy, or

macrosomia. All risk factors were included in the

multivariable logistic regression analysis except

epidural analgesia, nulliparity, and neonatal birth

weight. Epidural analgesia was excluded because

only one delivery with OASIS involved epidural

analgesia, while nulliparity and neonatal birth weight

were excluded due to their strong correlation with

vaginal nulliparity and macrosomia, respectively.

Macrosomia was considered to have greater clinical

relevance than neonatal birth weight because a

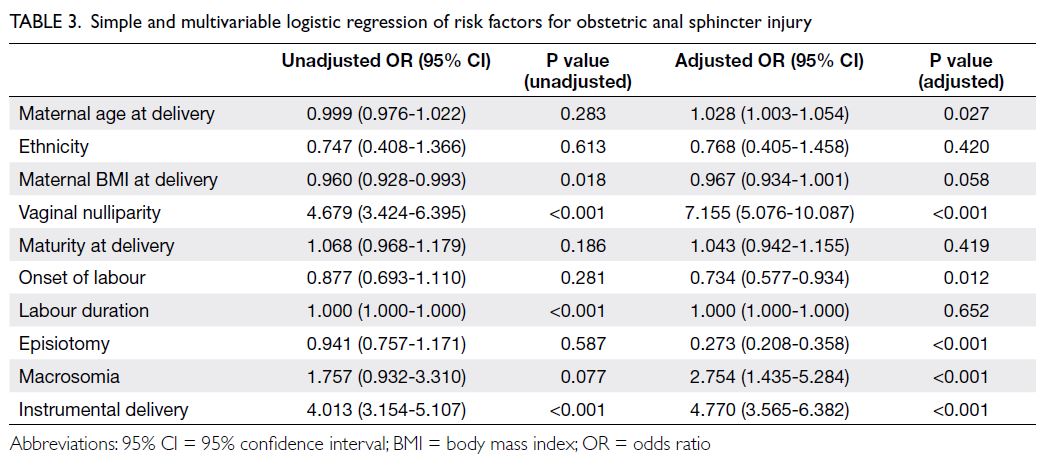

standard cut-off value exists. Multivariable logistic

regression analysis revealed that vaginal nulliparity

and instrumental delivery remained independent risk

factors for OASIS, whereas BMI and labour duration

did not. Induced labour (odds ratio [OR]=0.734,

95% confidence interval [CI]=0.577-0.934; P=0.012)

and episiotomy (OR=0.273, 95% CI=0.208-0.358;

P<0.001) were identified as protective factors,

while macrosomia (OR=2.754, 95% CI=1.435-5.284;

P<0.001) was identified as a risk factor for OASIS (Table 3). Missing data were noted for BMI in 543 cases (1.2%) and for onset of labour in 82 cases

(0.2%).

Table 2. Characteristics of the study population and comparison between women with and without obstetric anal sphincter injury (n=43 732)

Table 3. Simple and multivariable logistic regression of risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury

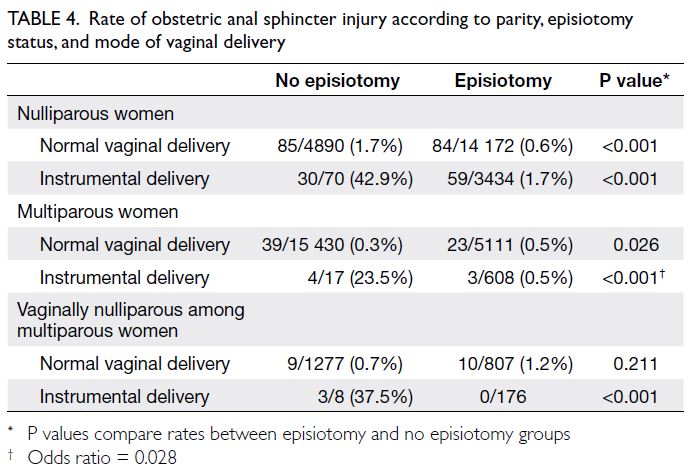

In the subgroup analysis of nulliparous women,

the OASIS rate was significantly lower among those

undergoing normal vaginal delivery with episiotomy

compared to those without (0.6% vs 1.7%; P<0.001)

and those undergoing instrumental delivery with

episiotomy (1.7% vs 42.9%; P<0.001). Among

multiparous women, the OASIS rate was significantly

lower in those undergoing normal vaginal delivery

without episiotomy (0.3% vs 0.5%; P=0.026) and those

undergoing instrumental delivery with episiotomy (0.5% vs 23.5% without episiotomy; P<0.001). Among

vaginally nulliparous women within the multiparous

group, no statistically significant difference in

OASIS rates was observed between normal vaginal

deliveries with and without episiotomy; however,

the OASIS rate was significantly lower among those

undergoing instrumental deliveries with episiotomy

compared with those without (0% vs 37.5%; P<0.001)

[Table 4].

Table 4. Rate of obstetric anal sphincter injury according to parity, episiotomy status, and mode of vaginal delivery

Discussion

In recent years, many obstetric units in Hong

Kong have promoted a reduction in episiotomy

use in recent years. Our unit achieved substantial

reductions in episiotomy rates among nulliparous

and multiparous women between 2012 and 2021.

Although the overall rate of OASIS remained low,

considerable increases were observed in both

groups during the study period. Vaginal nulliparity

and operative vaginal delivery were identified as

independent risk factors for OASIS, consistent with

previous findings.7 11 Furthermore, episiotomy was

identified as a protective factor against OASIS in

multivariable logistic regression analysis (OR=0.273,

95% CI=0.208-0.358) [Table 3].

In nulliparous women, episiotomy was

protective against OASIS in both normal and

instrumental vaginal deliveries. These findings

differ from those of previous large-scale studies.7 11

In a large retrospective study in the Netherlands

involving over 281 000 vaginal deliveries,13 and in

another study including more than 10 000 women

in Australia,14 mediolateral episiotomy was shown to reduce the risk of OASIS in nulliparous women

(OR=0.2113 and 0.54,14 respectively). However,

Mahgoub et al11 in France reported no association

between episiotomy and OASIS. In their cohort of

42 626 women, the overall OASIS rate was 1.2% and

the overall episiotomy rate was only 10%.11 Perrin et al7

reported an episiotomy rate of 63.2% in nulliparous

women and an OASIS rate of 0.7%, regardless of

episiotomy use. In their analysis, episiotomy was not

associated with OASIS in normal vaginal delivery

but appeared to be protective in nulliparous women

undergoing operative vaginal delivery at term.7

The above studies mainly involved women in

Western populations. Several studies have indicated

that Asian women have a two- to nine-fold increased

risk of sustaining OASIS.15 16 17 18 19 In a study conducted

in Israel involving over 80 000 women, including

997 of Asian origin, the OASIS rate among Asian

women was 9 times higher than that among women

of Western descent (3.5% vs 0.4%; P=0.001).16 Asian

women also had a higher proportion of fourth-degree

tears (17.1% vs 6.6%; P=0.039), despite smaller

newborns (mean birth weight: 3318 g vs 3501 g;

P=0.004).16 Anatomical differences between ethnic

groups may contribute to this disparity. Cheung et al9

reported that pregnant women of East Asian origin

had a thicker pubovisceral muscle, a smaller levator

hiatus, and reduced pelvic organ mobility compared

with pregnant women of Western descent. These

factors may contribute to the higher risk of OASIS.9

Moreover, Bates et al20 found that a shorter perineal

length measured during the second stage of labour

prior to pushing was significantly associated with

OASIS. Although a study conducted in Hawaii

found no significant difference in perineal body length between Western and Chinese women,

measurements were taken during the first stage of

labour rather than before pushing.21 Further studies

are needed to determine whether perineal body

length differs during the second stage of labour. The

reasons for the higher OASIS rates among Asian

women remain unclear but are likely to be complex

and multifactorial.

Another notable point is the higher rate of

epidural analgesia use among Western women

compared with Asian women (50%-90% vs 0%-2.2%),

even within the same hospital setting where epidural

analgesia is offered free of charge to all women.7 11 16 20

In the present study, the rate of epidural analgesia

was low throughout the study period. In this cohort,

epidural analgesia was not associated with OASIS.

A meta-analysis examining risk factors for OASIS

found no association with epidural analgesia;

however, it included only two studies.22 In contrast,

Mahgoub et al11 identified epidural analgesia as a

protective factor for OASIS, whereas another meta-analysis

reported it as a risk factor.19 These conflicting

findings suggest that the role of epidural analgesia in

OASIS remains unclear.

There is limited literature on the role of

episiotomy in normal vaginal delivery among

multiparous women. In the present study, episiotomy

did not protect multiparous women from OASIS,

except in the context of instrumental vaginal delivery.

Indeed, episiotomy may increase the risk of OASIS

in this group.23 However, we noted that episiotomy

was protective against OASIS among multiparous

women undergoing instrumental vaginal delivery

(OR=0.028). This finding is supported by a Dutch

study which reported five-fold and ten-fold

reductions in OASIS during vacuum and forceps

deliveries, respectively.24 In light of these findings, we recommend a more restrictive approach to episiotomy among multiparous women undergoing normal vaginal delivery.

The rising trend of OASIS over the past

decade may also be attributable to improvements

in clinical detection following the promotion of

more thorough post-delivery assessments by both

midwives and obstetricians. Kwok et al25 reported

that the prevalence of occult OASIS—detected by

endoanal ultrasound but not identified by clinical

examination after delivery—was as high as 7.8% after

normal vaginal delivery and 3.8% after instrumental

delivery. Subsequently, regular OASIS workshops

were introduced to train midwives and doctors

in performing standardised vaginal and rectal

examinations after vaginal delivery. When a major

perineal tear is suspected, immediate reassessment

by an obstetric specialist is conducted. This practice has been shown to improve the detection rate of

OASIS.26 We also analysed trends in instrumental

vaginal delivery over the 10-year period. Overall,

decreasing trends were observed for both

instrumental and ventouse deliveries. The rate of

forceps delivery remained similar or showed a slight

decrease, except in 2021. Therefore, the rising trend

in OASIS is unlikely to be explained by changes in

instrumental delivery rates.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include its large sample size,

10-year study period, and the documented reduction

in episiotomy rates, which allowed evaluation of the

role of episiotomy in OASIS. Our unit is a tertiary

centre with the highest delivery volume in Hong

Kong, and this represents the largest retrospective

study to date focusing on an Asian population.

However, as a retrospective study, missing data were

noted during data collection and entry. In addition,

several risk factors previously identified in meta-analyses—such as the duration of the second stage

of labour, fetal head position at delivery, history of

previous OASIS, and shoulder dystocia—were not

analysed in the present study,19 27 representing a key

limitation. Furthermore, some cases of OASIS may

have been missed on clinical examination. High-quality

research is needed to further investigate

OASIS, given its substantial impact on women’s

quality of life.

Conclusion

With a substantial reduction in episiotomy rates,

a corresponding increase in the rate of OASIS

was observed. Episiotomy was protective against

OASIS among nulliparous women undergoing

singleton normal vaginal delivery and instrumental

delivery. It also conferred protection in multiparous

women undergoing instrumental delivery but not

in those having normal vaginal delivery. Among

vaginally nulliparous women within the multiparous

group, the OASIS rate was significantly higher in

those undergoing instrumental deliveries without

episiotomy, similar to the rate observed in nulliparous

women. Conversely, the OASIS rate was higher

in the episiotomy group during normal vaginal

delivery, although this difference was not statistically

significant and may have been influenced by the

small sample size. Further high-quality research

is warranted, and women should be informed of

these findings to enable informed decision-making

regarding episiotomy.

Author contributions

Concept or design: SSC Chan, RYK Cheung.

Acquisition of data: SSC Chan, RYK Cheung, TW Chau, YY Lau, SM Ng, TM Tso.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SSC Chan, YY Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: YY Lau.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SSC Chan, RYK Cheung, TW Chau, YY Lau, SM Ng, TM Tso.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SSC Chan, YY Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: YY Lau.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Ms LL Lee, our research assistant, for her assistance with data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation.

Declaration

Findings from this study were partially presented as an e-poster

at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

World Congress 2024, Muscat, Oman, 15-17 October 2024.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was obtained from the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical

Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2022.259).

The requirement for patient consent was waived by the

Committee due to the retrospective nature of the research.

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and the

International Council for Harmonization Guideline for Good

Clinical Practice.

References

1. Tung CW, Cheon WC, Tong WM, Leung HY. Incidence

and risk factors of obstetric anal sphincter injuries after

various modes of vaginal deliveries in Chinese women.

Chin Med J (Engl) 2015;128:2420-5. Crossref

2. Jangö H, Langhoff-Roos J, Rosthøj S, Sakse A. Modifiable

risk factors of obstetric anal sphincter injury in primiparous

women: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obst

Gynecol 2014;210:59.e1-6. Crossref

3. Hsieh WC, Liang CC, Wu D, Chang SD, Chueh HY,

Chao AS. Prevalence and contributing factors of severe

perineal damage following episiotomy-assisted vaginal

delivery. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2014;53:481-5. Crossref

4. Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, et al. Third- and

fourth-degree perineal tears among primiparous

women in England between 2000 and 2012: time trends

and risk factors. BJOG 2013;120:1516-25. Crossref

5. Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Territory-wide Audit in Obstetrics & Gynaecology.

2014. Available from: https://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/Download/Territory-wide_Audit_in_Obstetrics_Gynaecology_2014.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2020.

6. Woolley RJ. Benefits and risks of episiotomy: a review of

the English-language literature since 1980. Part II. Obstet

Gynecol Surv 1995;50:821-35. Crossref

7. Perrin A, Korb D, Morgan R, Sibony O. Effectiveness of episiotomy to prevent OASIS in nulliparous women at

term. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2023;162:632-8. Crossref

8. Abdool Z, Dietz HP, Lindeque BG. Ethnic differences in

the levator hiatus and pelvic organ descent: a prospective

observational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2017;50:242-6. Crossref

9. Cheung RY, Shek KL, Chan SS, Chung TK, Dietz HP.

Pelvic floor muscle biometry and pelvic organ mobility in

East Asian and Caucasian nulliparae. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol 2015;45:599-604. Crossref

10. Brown J, Kapurubandara S, Gibbs E, King J. The great

divide: country of birth as a risk factor for obstetric anal

sphincter injuries. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2018;58:79-85. Crossref

11. Mahgoub S, Piant H, Gaudineau A, Lefebvre F, Langer B,

Koch A. Risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injuries

(OASIS) and the role of episiotomy: a retrospective series

of 496 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2019;48:657-62. Crossref

12. de Leeuw JW, Struijk PC, Vierhout ME, Wallenburg HC.

Risk factors for third degree perineal ruptures during

delivery. BJOG 2001;108:383-7. Crossref

13. Okeahialam NA, Taithongchai A, Thakar R, Sultan AH.

The incidence of anal incontinence following obstetric anal

sphincter injury graded using the Sultan classification: a

network meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023;228:675-88.e13. Crossref

14. Hauck YL, Lewis L, Nathan EA, White C, Doherty DA.

Risk factors for severe perineal trauma during vaginal

childbirth: a Western Australian retrospective cohort

study. Women Birth 2015;28:16-20. Crossref

15. Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, et al. Racial and ethnic

disparities in maternal morbidity and obstetric care. Obst

Gynecol 2015;125:1460-7. Crossref

16. Baruch Y, Gold R, Eisenberg H, et al. High incidence of

obstetric anal sphincter injuries among immigrant women

of Asian ethnicity. J Clin Med 2023;12:1044. Crossref

17. D’Souza JC, Monga A, Tincello DG. Risk factors for

perineal trauma in the primiparous population during non-operative

vaginal delivery. Int Urogynecol J 2020;31:621-5. Crossref

18. Yeaton-Massey A, Wong L, Sparks TN, et al. Racial/ethnic

variations in perineal length and association with perineal

lacerations: a prospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal

Neonatal Med 2015;28:320-3. Crossref

19. Hu Y, Lu H, Huang Q, et al. Risk factors for severe perineal

lacerations during childbirth: a systematic review and

meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Clin Nurs 2023;32:3248-65. Crossref

20. Bates LJ, Melon J, Turner R, Chan SS, Karantanis E.

Prospective comparison of obstetric anal sphincter injury

incidence between an Asian and Western hospital. Int

Urogynecol J 2019;30:429-37. Crossref

21. Tsai PJ, Oyama IA, Hiraoka M, Minaglia S, Thomas J,

Kaneshiro B. Perineal body length among different racial

groups in the first stage of labor. Female Pelvic Med

Reconstr Surg 2012;18:165-7. Crossref

22. Barba M, Bernasconi DP, Manodoro S, Frigerio M. Risk

factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury recurrence: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet

2022;158:27-34. Crossref

23. Eggebø TM, Rygh AB, von Brandis P, Skjeldestad FE.

Prevention of obstetric anal sphincter injuries with

perineal support and lateral episiotomy: a historical cohort

study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2024;103:488-97. Crossref

24. van Bavel J, Hukkelhoven CW, de Vries C, et al. The

effectiveness of mediolateral episiotomy in preventing

obstetric anal sphincter injuries during operative vaginal

delivery: a ten-year analysis of a national registry. Int

Urogynecol J 2018;29:407-13. Crossref

25. Kwok SP, Wan OY, Cheung RY, Lee LL, Chung JP, Chan SS.

Prevalence of obstetric anal sphincter injury following

vaginal delivery in primiparous women: a retrospective

analysis. Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:271-8. Crossref

26. Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Occult anal

sphincter injuries—myth or reality? BJOG 2006;113:195-200. Crossref

27. Pergialiotis V, Bellos I, Fanaki M, Vrachnis N,

Doumouchtsis SK. Risk factors for severe perineal trauma

during childbirth: an updated meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet

Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;247:94-100. Crossref