Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 29 Jan 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Influenza and Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis in children: could we be missing them and why?

Julian WT Tang, MB, BS, FRCP1,2; KL Hon, MB, BS, MD3

1 Clinical Microbiology, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, Leicester, United Kingdom

2 Department of Respiratory Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom

3 Department of Paediatrics, CUHK Medical Centre, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof KL Hon (ehon@cuhk.edu.hk)

We note the case of influenza A encephalopathy

reported in the Hong Kong Medical Journal in 2020,

involving an unvaccinated 10-year-old child who

presented with high fever, convulsions, and altered

consciousness.1 The patient was successfully treated

with anticonvulsants, oseltamivir, and hypertonic

saline and mannitol to control cerebral oedema. The

electroencephalogram showed diffuse slow-wave

activity.1 Although Hong Kong offers a free seasonal

influenza vaccination programme for children aged

6 months to under 12 years (those attending primary

school), uptake remains relatively low (50%-60%),2

and several paediatric influenza-related deaths

are reported annually in the city, primarily among

unvaccinated children.3

A diagnosis of influenza encephalitis is

made after exclusion of all other possible causes,

following confirmed detection of influenza virus in a

respiratory sample, but only very rarely by detection

of influenza RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Clinical presentation can be variable, including

fever, seizures, meningism, photophobia, excessive

sleepiness, disorientation, agitation, altered

personality, and leg paresis. Electroencephalogram

findings can show diffuse slowing or generalised

spike-wave activity, while magnetic resonance

imaging may be normal or show multiple focal

lesions.4

This form of ‘indirect’ diagnosis in viral

encephalitis is not unique to influenza. Among other

viral encephalitis—such as West Nile virus, Japanese

encephalitis virus, and tick-borne encephalitis

viruses—diagnosis is often confirmed by serology or

seroconversion as the virus may have already cleared

from the CSF by the time patients with neurological

symptoms present. Concerning influenza

encephalitis, virus detection in a respiratory

sample by polymerase chain reaction is a common

diagnostic approach. Treatment of influenza in

otherwise healthy children is often not required;

whether treated or not, the clinical outcomes of

presumed influenza encephalitis are generally good,

especially when oseltamivir and neurosupportive

treatment are promptly instituted.5

A practical diagnostic distinction has been made between acute influenza encephalitis—occurring within a few days of confirmed infection

and influenza encephalopathy, which occurs within

3 weeks after diagnosis, after respiratory symptoms

have resolved.4 6 Clinical treatment is essentially the

same.7 8

Another underrecognised cause of encephalitis

is Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the usual cause of

glandular fever in teenagers and young adults. An

important differential diagnosis is streptococcal

pharyngitis or tonsillitis. We have encountered

unwell teenagers with tonsillitis, cervical

lymphadenitis, atypical lymphocytosis, and normal

inflammatory markers but negative rapid throat

streptococcal antigen test results. Prompt diagnosis

of EBV glandular fever can help avoid unnecessary

antibiotics (personal communication). Epstein-Barr virus is a herpesvirus that becomes latent in

B lymphocytes after primary infection, which is

often asymptomatic. Reviews of EBV encephalitis

suggest it is more common than previously thought,

particularly in children.9 10 11 12 13 As with influenza, most

cases resolve spontaneously with few sequelae, and

the diagnostic criteria remain poorly defined.

In EBV encephalitis, EBV DNA is more

frequently detected in CSF polymerase chain

reaction, particularly in cases that involve reactivated

EBV infection.9 However, such EBV DNA–positive

CSF results are often interpreted and dismissed as

benign ‘bystander’ EBV reactivations assumed to

play no role in the current illness.

Similar to influenza encephalitis, EBV

encephalitis presents with a wide range of

symptoms, including headache, fever, nausea,

vomiting, tonsillitis, myalgia, and neurological

manifestations such as cerebellar syndromes, tonic-clonic

seizures, meningism, hypotonia, myalgia,

psychiatric disorders, and cognitive, sensory or visual

impairments. Brain imaging may show white matter

changes in the cerebellum, basal ganglia, frontal

lobe, and cerebral cortex, and electroencephalogram

findings may be normal or indicate diffuse slowing.9

However, none of these features is specific to EBV

encephalitis and may also be found with other viral

causes.

Diagnosis of EBV encephalitis is therefore

often made by exclusion when no other pathogen

is identified. Where treatment has been initiated,

intravenous acyclovir or ganciclovir (although

neither is licensed for EBV treatment) has been used,

with or without corticosteroids—or corticosteroids

alone, often with good outcomes.9 Although the

direct efficacy of acyclovir and ganciclovir against

EBV encephalitis is doubtful, they may help suppress

concurrent reactivation of herpes simplex virus

(HSV)–1, which could otherwise lead to more severe

HSV-1 encephalitis.

Acute encephalitis due to dual or simultaneous

coinfections by EBV and influenza is theoretically

possible and may cause diagnostic dilemma.

However, a PubMed review of literature does not

identify any report. In any case, treatment will

essentially be the same by using specific antiviral

medications for both viruses.

Viral encephalitis is inflammation of the brain

caused by a virus.14 Diagnosis is based on symptoms,

travel history, and investigations such as histology,

imaging, and lumbar puncture. Many viruses can cause

encephalitis.15 These viruses often replicate outside

the central nervous system before triggering diverse

forms of viral encephalitis. Differential diagnosis

helps rule out non-infectious encephalitis.14 Some

viruses have characteristic symptoms of infection

that may aid diagnosis.16 A broad differential

diagnosis should be considered, including infectious

and non-infectious aetiologies (eg, malignancy,

autoimmune or paraneoplastic encephalitis, abscess, tuberculosis, drug reactions, vascular or

metabolic disease).15 16 17 It may not always be possible

to distinguish viral encephalitis from immune-mediated

inflammatory central nervous system

diseases (eg, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

and immune-mediated encephalitis) in children.18

Symptoms usually occur acutely, with fever, stiff

neck, headache, altered mental status, photophobia,

vomiting, confusion, and, in severe cases, seizures,

paralysis, or coma.16 18 Most cases are mild.15

Neuroimaging and lumbar puncture are essential14;

computed tomography or magnetic resonance

imaging can identify increased intracranial pressure

and the risk of uncal herniation. Cerebrospinal

fluid should be analysed for opening pressure, cell

counts, glucose, protein, and immunoglobulin G and

immunoglobulin M antibodies. Polymerase chain

reaction testing for HSV-1, HSV-2, and enteroviruses

is also recommended. Where indicated, brain

biopsy and body fluid specimen cultures may assist.

Electroencephalogram findings are abnormal in

over 80% of viral encephalitis cases, and continuous

monitoring may be needed to identify nonconvulsive

status epilepticus.15 18

Thus, if clinical outcomes are generally good

with current non-specific supportive management

protocols, even in the absence of a specific cause,

there may be little additional value in defining

a precise diagnosis. Brain biopsy to confirm the

exact cause is usually unnecessary. Treatment is

usually supportive, with antivirals such as acyclovir

for herpes simplex encephalitis. Where specific

treatment (eg, oseltamivir for influenza) is available,

it should be used because it may alleviate encephalitic

symptoms. Furthermore, once a diagnosis of

encephalitis is made, the clinical team can avoid

extensive investigation for other causes, reassured

that most cases resolve with appropriate supportive

care and good outcomes.

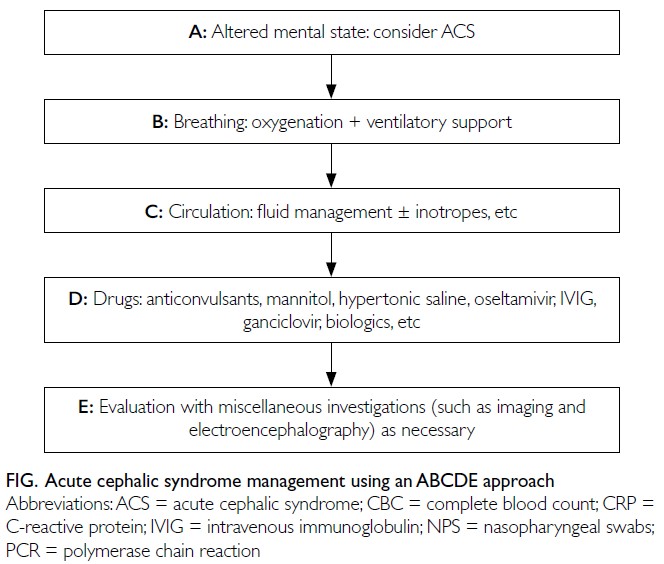

In conclusion, infection or infectionassociated

encephalitis and encephalopathy can

often be managed empirically. A definitive diagnosis

can support targeted antiviral therapy and reduce

unnecessary investigations, provided the diagnosis

is robust. We propose a flowchart to guide frontline

physicians and paediatricians in the diagnosis and

management of these conditions (Fig). Because it

is often impractical or impossible to confirm the

presence of the causative infectious agent in the brain

parenchyma, there is limited relevance in labelling

the condition as encephalitis or encephalopathy. The

term acute cephalic syndrome (ACS) may be more

appropriate. The cardinal symptom of ACS is an

altered or fluctuating mental state. Irrespective of

whether the aetiology is infectious, para-infectious,

or non-infectious, the ABCDE approach should aid

physicians during initial management of patients

with ACS.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the concept or design,

acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting

of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. Both authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in

the peer review process. The other author has declared no

conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Hon KL. Successful treatment of influenza A

encephalopathy. Hong Kong Med J 2020;26:154. Crossref

2. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Seasonal influenza vaccination

& pneumococcal vaccination arrangement for 2020/21.

Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/sivpv_vaccination_arrangement_for_2020_2021.pdf . Accessed 31 Jan 2025.

3. Hon KL, Tang JW. Low mortality and severe complications

despite high influenza burden among Hong Kong children.

Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:497-8. Crossref

4. Steininger C, Popow-Kraupp T, Laferl H, et al. Acute

encephalopathy associated with influenza A virus infection.

Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:567-74. Crossref

5. Hui WF, Leung KK, Au CC, et al. Clinical characteristics

and outcomes of acute childhood encephalopathy in a

tertiary pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Emerg Care

2022;38:115-20. Crossref

6. Edet A, Ku K, Guzman I, Dargham HA. Acute

influenza encephalitis/encephalopathy associated with

influenza a in an incompetent adult. Case Rep Crit Care 2020;2020:6616805. Crossref

7. Ochi N, Takahashi K, Yamane H, Takigawa N. Acute

necrotizing encephalopathy in an adult with influenza A

infection. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018;14:753-6. Crossref

8. Au CC, Hon KL, Leung AK, Torres AR. Childhood

infectious encephalitis: an overview of clinical features,

investigations, treatment, and recent patents. Recent Pat

Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2020;14:156-65. Crossref

9. Peuchmaur M, Voisin J, Vaillant M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus

encephalitis: a review of case reports from the last 25 years.

Microorganisms 2023;11:2825. Crossref

10. Hashemian S, Ashrafzadeh F, Akhondian J, Beiraghi Toosi M.

Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis: a case report. Iran J Child

Neurol 2015;9:107-10.

11. Akkoc G, Kadayifci EK, Karaaslan A, et al. Epstein-Barr

virus encephalitis in an immunocompetent child: a case

report and management of Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis.

Case Rep Infect Dis 2016;2016:7549252. Crossref

12. Cheng H, Chen D, Peng X, Wu P, Jiang L, Hu Y. Clinical

characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus infection in the

pediatric nervous system. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20:886. Crossref

13. Rzhevska OO, Khodak LA, Butenko AI, et al. EBV-encephalitis in children: diagnostic criteria. Wiad Lek

2023;76:2263-8.Crossref

14. Venkatesan A, Tunkel AR, Bloch KC, et al. Case definitions,

diagnostic algorithms, and priorities in encephalitis:

consensus statement of the international encephalitis

consortium. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:1114-28. Crossref

15. Said S, Kang M. Viral encephalitis. StatPearls. 8 August

2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470162/. Accessed 28 Mar 2025.

16. Schibler M, Eperon G, Kenfak A, Lascano A, Vargas MI,

Stahl JP. Diagnostic tools to tackle infectious

causes of encephalitis and meningoencephalitis in

immunocompetent adults in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect

2019;25:408-14. Crossref

17. Bradshaw MJ, Venkatesan A. Herpes simplex virus–1

encephalitis in adults: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and

management. Neurotherapeutics 2016;13:493-508. Crossref

18. Costa BK, Sato DK. Viral encephalitis: a practical review

on diagnostic approach and treatment. J Pediatr (Rio J)

2020;96 Suppl 1:12-9. Crossref