Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 29 Jan 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PERSPECTIVE

From workplace-based assessment to

programmatic assessment: continuing the

evolution of medical assessment to support

competency-based medical education

HY So, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)1; Albert KM Chan, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)2; Benny CP Cheng, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)2

1 Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 The Jockey Club Institute for Medical Education and Development, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr HY So (sohingyu@fellow.hkam.hk)

Introduction

In our article on workplace-based assessment (WBA),

we outlined how WBAs represent an important step

in the evolution of medical education assessment.1

By focusing on real-time evaluation and providing

formative feedback, WBAs allow learners to refine

their clinical performance in actual patient-care

settings. However, WBAs alone—similar to any

single assessment method—have limitations. As van

der Vleuten2 noted, no single assessment method

can comprehensively meet all quality criteria, such

as reliability, validity, educational impact, and cost.

Reliance on a single approach limits the breadth of

information that can be gathered about a learner’s

abilities, much like relying on a single laboratory test

to diagnose a complex medical condition.

Programmatic assessment overcomes these

limitations by combining multiple assessment

methods in a complementary fashion to provide

a more comprehensive and accurate evaluation of

learner competence.3 4 This approach—a cornerstone

of competency-based medical education (CBME)—offers a more holistic and continuous form of

assessment.5 In this article, we discuss the rationale

behind the shift from traditional assessments to

programmatic assessment, the principles that

underlie this model, and how it can be successfully

implemented in postgraduate medical training

programmes.

Limitations of traditional

assessment

Traditional assessments often rely heavily on

high-stakes examinations at the end of a course or

programme. Although these examinations serve a

purpose, they fail to fully support the development

of clinical competence as required in CBME.5

High-stakes examinations typically induce anxiety,

promote short-term memorisation, and do not

capture the complexities of real-world clinical

decision-making. When examinations are regarded as make-or-break moments, learners often shift

their focus from genuine understanding to mere

performance, which does not support long-term

mastery.6

Several specific limitations of traditional

assessments include:

Programmatic assessment is designed to

address these shortcomings. By incorporating

multiple data points and reducing reliance on any

single examination, it provides a more nuanced and

comprehensive evaluation of learners’ progression

and competencies.

Core principles of programmatic

assessment

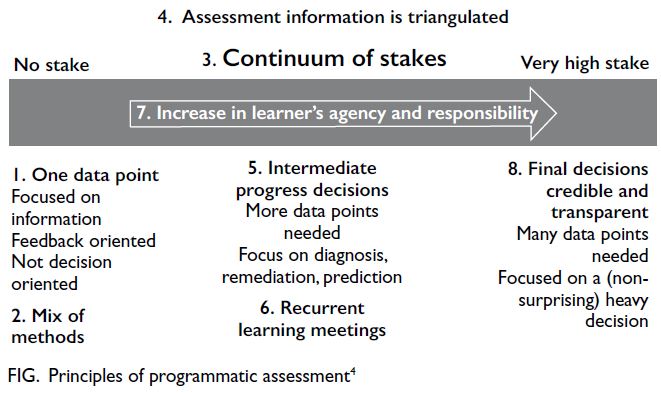

Programmatic assessment is based on a set of

principles derived from educational theories10 that

promote a comprehensive, learner-centred approach

to medical education (Fig4):

1. “Every assessment is but a data point, which

should be optimised for learning by giving

meaningful feedback to the learner. Pass/fail

decisions are not given on a single data-point.”4

No single assessment can reliably determine a learner’s progression. In programmatic assessment, each assessment—whether formative or summative—contributes to a cumulative understanding of the learner’s abilities. This is similar to using multiple diagnostic tools to form a complete clinical picture. Overall judgement of the learner’s competence is made by aggregating these data points over time. At this stage, the focus is on providing meaningful feedback to facilitate learning.4

2. “Use a mix of assessment methods; the choice of method depends on the educational justification for using that method.”4

Competence in medical practice is multidimensional, and different assessment methods capture distinct facets of a learner’s development. Programmatic assessment uses a mix of standardised tests (such as multiple-choice examinations or objective structured clinical examinations [OSCEs]) and non-standardised methods (such as narrative feedback or direct observation during WBAs). This approach mirrors clinical practice, where a combination of laboratory tests, imaging, and clinical examinations provides a comprehensive understanding of a patient’s condition.4

No single assessment can reliably determine a learner’s progression. In programmatic assessment, each assessment—whether formative or summative—contributes to a cumulative understanding of the learner’s abilities. This is similar to using multiple diagnostic tools to form a complete clinical picture. Overall judgement of the learner’s competence is made by aggregating these data points over time. At this stage, the focus is on providing meaningful feedback to facilitate learning.4

2. “Use a mix of assessment methods; the choice of method depends on the educational justification for using that method.”4

Competence in medical practice is multidimensional, and different assessment methods capture distinct facets of a learner’s development. Programmatic assessment uses a mix of standardised tests (such as multiple-choice examinations or objective structured clinical examinations [OSCEs]) and non-standardised methods (such as narrative feedback or direct observation during WBAs). This approach mirrors clinical practice, where a combination of laboratory tests, imaging, and clinical examinations provides a comprehensive understanding of a patient’s condition.4

For standardised assessments, it is

important to recognise that competence is

content-specific—a learner’s performance in one

scenario or question may not reliably predict

performance in another. Thus, standardised

assessments require large samples of data

to ensure reliability. This applies equally to

objective tests (eg, multiple-choice questions)

and more subjective assessments, such as oral

examinations. Broad sampling of questions

and examiners enhances validity. Additionally,

quality assurance measures must be established

to ensure fairness and relevance to intended

competencies.10

For non-standardised assessments, the

emphasis lies in real-life application and

expert judgement. Bias is inherent, but it can

be minimised by using multiple assessors and

multiple assessments over time. Feedback

should be narrative, offering deeper insights

into performance. Validity depends on adequate

preparation of both trainers and trainees.11

3. “Distinction between summative and formative is

replaced by a continuum of stakes, and decision-making

on learner progress is proportionally

related to the stakes.”4

In traditional assessments, the distinction between formative (low-stakes) and summative (high-stakes) is clear. In programmatic assessment, this becomes more fluid. Low-stakes assessments guide learning and improvement, while high-stakes assessments are used for certification or other key decisions. The amount of evidence required is proportional to the stakes involved, similar to monitoring a patient’s condition over time—minor issues are addressed early on, whereas major decisions (eg, surgery) are based on cumulative understanding of the patient’s health.4

4. “Assessment information is triangulated across data-points.”4

Information pertaining to the same content is triangulated, similar to synthesising laboratory results, imaging, and patient history in diagnosis. For example, history-taking skills can be assessed using an OSCE, a mini-clinical evaluation exercise, and patient feedback. This method of aggregating results is more meaningful than aggregating by test format.4

5. “Intermediate reviews are made to discuss and decide with the learner on their progress.”4

Learners meet regularly with mentors or supervisors to reflect on feedback and adjust learning plans, much like adjusting a treatment based on new laboratory results. These intermediate reviews prevent surprising high-stakes decisions at the end of the programme.4

6. “Learners have recurrent learning meetings with faculty using a self-analysis of all assessment data.”4

Self-assessment is critical for learners to become self-directed professionals. Learners are encouraged to review their portfolio data and discuss with mentors. Initially, guidance from trainers is required for self-assessment to foster deeper learning and professional development.4

7. “Learners are increasingly accountable for their learning.”4

Over time, learners are expected to take greater responsibility for their learning, similar to patients who assume greater ownership of their health as they become more informed about their condition. This shift in responsibility helps prepare learners for independent practice and fosters lifelong learning.4

8. “High-stakes decisions are made in a credible and transparent manner.”4

High-stakes decisions, such as those related to certification, are based on multiple assessments collected over time. This approach ensures that decisions are fair and reflect a holistic understanding of the learner’s competence. Much like the review of a complex clinical case by a multidisciplinary team, programmatic assessment enables thorough and transparent decision-making.4

In traditional assessments, the distinction between formative (low-stakes) and summative (high-stakes) is clear. In programmatic assessment, this becomes more fluid. Low-stakes assessments guide learning and improvement, while high-stakes assessments are used for certification or other key decisions. The amount of evidence required is proportional to the stakes involved, similar to monitoring a patient’s condition over time—minor issues are addressed early on, whereas major decisions (eg, surgery) are based on cumulative understanding of the patient’s health.4

4. “Assessment information is triangulated across data-points.”4

Information pertaining to the same content is triangulated, similar to synthesising laboratory results, imaging, and patient history in diagnosis. For example, history-taking skills can be assessed using an OSCE, a mini-clinical evaluation exercise, and patient feedback. This method of aggregating results is more meaningful than aggregating by test format.4

5. “Intermediate reviews are made to discuss and decide with the learner on their progress.”4

Learners meet regularly with mentors or supervisors to reflect on feedback and adjust learning plans, much like adjusting a treatment based on new laboratory results. These intermediate reviews prevent surprising high-stakes decisions at the end of the programme.4

6. “Learners have recurrent learning meetings with faculty using a self-analysis of all assessment data.”4

Self-assessment is critical for learners to become self-directed professionals. Learners are encouraged to review their portfolio data and discuss with mentors. Initially, guidance from trainers is required for self-assessment to foster deeper learning and professional development.4

7. “Learners are increasingly accountable for their learning.”4

Over time, learners are expected to take greater responsibility for their learning, similar to patients who assume greater ownership of their health as they become more informed about their condition. This shift in responsibility helps prepare learners for independent practice and fosters lifelong learning.4

8. “High-stakes decisions are made in a credible and transparent manner.”4

High-stakes decisions, such as those related to certification, are based on multiple assessments collected over time. This approach ensures that decisions are fair and reflect a holistic understanding of the learner’s competence. Much like the review of a complex clinical case by a multidisciplinary team, programmatic assessment enables thorough and transparent decision-making.4

Implementing programmatic

assessment

The implementation of programmatic assessment

clearly requires transformative changes to our

assessment system. The Royal College of Physicians

and Surgeons of Canada has adopted a Competence

by Design approach to implement CBME, serving

as a ‘hybrid’ model that blends a competency-based

framework within the existing system.12 Similarly, the

transition in our assessment system can be guided by

applying the following principles of programmatic

assessment while building on the structure of the

current framework.

Provide meaningful feedback

A cornerstone of programmatic assessment is

detailed feedback. Traditional methods such as grades or pass/fail results offer limited insight, whereas

narrative feedback can help learners understand

the nuances of their performance. While we have

highlighted the value of feedback in WBA, it should

also be incorporated into other forms of assessment.

For example, detailed feedback after an OSCE could

break down performance in communication, clinical

reasoning, and technical skills, helping learners

target areas for improvement.13

Establish a reliable system for collecting

information

All assessment data, including feedback, reflective

reports, and performance outcomes, must be

systematically collected to enable learners and

educators to monitor progress over time. e-Portfolios

play a crucial role in programmatic assessment,

serving as essential tools for tracking these data.

An effective e-portfolio should be user-friendly,

facilitating seamless access and integration across

various platforms.13 14

Organise intermediate assessments

Portfolios are only valuable if they are actively used to

promote learning. Regular intermediate assessments

play a key role by offering diagnostic, therapeutic,

and prognostic insights. These assessments ensure

that learners receive timely feedback on their

current performance, understand areas requiring

improvement, and have a clear sense of their future

trajectory. By providing of ongoing guidance, they

help prevent unexpected outcomes at the end of

programmes and enable timely interventions when

needed.13 14

Adapt high-stakes examinations for

competency-based medical education

Although CBME relies heavily on frequent low-stakes

assessments, high-stakes examinations

continue to hold value. However, these examinations

must be adapted to align with the CBME framework.

The optimal approach is still evolving. The Royal

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

has implemented several changes that are worth

considering.15

Earlier timing

Scheduling examinations earlier in training allows

learners to demonstrate competence sooner, freeing

up time in later stages to focus on clinical practice.

Integration with other assessments

Examinations should complement WBAs by

focusing on competencies that are more difficult to

assess in clinical settings, such as the management of

rare conditions.

Sequencing

Written examinations should precede practical

or oral examinations, ensuring learners have

the necessary foundational knowledge before

progressing to more complex skills.

Global rating scales

In practical examinations, transitioning from

checklists to global ratings encourages the

assessment of higher-order clinical decision-making,

rather than rote memorisation of facts.

Updated psychometrics

New psychometric approaches focus on decision

consistency, ensuring that examinations measure

true competence rather than simply comparing

learners with their peers.

Promote faculty development

As assessment methods and tools are only as

effective as the faculty who utilise them, it is essential

that faculty develop the competencies required for

accurate assessment and effective feedback. Strong

leadership, supported by a committed faculty, has

been identified as the most important factor enabling

implementation of programmatic assessment.16 17

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine has developed

a comprehensive faculty development framework

for trainers, examiners, supervisors of training, and

collegial leads.18 Additionally, it is crucial to prepare

trainees for this new assessment model. Training

programmes are either currently in place or will

soon be introduced to support and facilitate this

transition.

Ensure reliable decision-making

For high-stakes decisions, such as passing or

promoting a learner, it is essential to consider a

comprehensive range of data gathered from diverse

settings, methods, and assessors. These data should

include both quantitative measures and qualitative

feedback, such as written or verbal evaluations.

Professional judgement is required to effectively

interpret and synthesise this information. Given

the significant consequences of these decisions,

it is critical to ensure that the process is fair and

trustworthy.12 To support the integrity of this

decision-making process, recommendations have

been established for procedural measures and

quality assurance frameworks.8 19

Evaluate and adapt the programme

Like any curriculum, an assessment programme

must undergo regular evaluation to identify potential

issues and areas for improvement. Continuous

monitoring ensures the programme remains aligned with its goals and is responsive to learner and faculty

feedback. This process is essential to maintain

the relevance and effectiveness of programmatic

assessment.13

Conclusion

Programmatic assessment represents a major

advancement in medical education by integrating

diverse assessment methods, providing continuous

feedback, and using multiple data points to make

informed decisions. This learner-centred approach

helps ensure that future clinicians are equipped to

meet the challenges of modern healthcare, much like

a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment plan

supports better outcomes for patients.

As articulated in our Position Paper on

Postgraduate Medical Education,9 we are progressing

along the journey towards CBME, within which

programmatic assessment is a key component. In

this context, there is a clear need to review Hong

Kong’s assessment systems to ensure alignment

with CBME principles. However, such progression

does not imply the complete replacement of high-stakes

examinations. Even in countries that have

advanced further along the CBME journey, high-stakes

examinations continue to serve important

roles in maintaining standards and ensuring public

accountability.15 The priority, therefore, is not to

abolish such examinations but to integrate them

within a programmatic framework that values

multiple sources of evidence, meaningful feedback,

and longitudinal decision-making. The evolution

towards programmatic assessment should be

viewed as a gradual and deliberate process requiring

sustained faculty development, structural support,

and system-level coordination.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: HY So.

Analysis or interpretation of data: HY So, AKM Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: HY So.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: HY So.

Analysis or interpretation of data: HY So, AKM Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: HY So.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency

in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. So HY, Choi YF, Chan PT, Chan AK, Ng GW, Wong GK.

Workplace-based assessments: what, why, and how to

implement? Hong Kong Med J 2024;30:250-4. Crossref

2. van der Vleuten CP. The assessment of professional

competence: developments, research and practical implications. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 1996;1:41-67. Crossref

3. Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. Programmatic

assessment: from assessment of learning to assessment for

learning. Med Teach 2011;33:478-85. Crossref

4. Henneman EA, Cunningham H. Ottawa 2020 consensus

statement for programmatic assessment—1. Agreement

on the principles. Med Teach 2021;43:1139-48. Crossref

5. Van Melle E, Frank JR, Holmboe ES, et al. A core

components framework for evaluating implementation

of competency-based medical education programs. Acad

Med 2019;94:1002-9. Crossref

6. Bok HG, Teunissen PW, Favier RP, et al. Programmatic

assessment of competency-based workplace learning:

when theory meets practice. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:123. Crossref

7. Cilliers FJ, Schuwirth LW, Herman N, Adendorff HJ, van

der Vleuten CP. A model of the pre-assessment learning

effects of summative assessment in medical education. Adv

Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2012;17:39-53. Crossref

8. van der Vleuten C, Heeneman S, Schuwirth LW.

Programmatic assessment. In: Dent J, Harden RM, Hunt D,

editors. A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers. 6th ed.

Elsevier; 2021: 295-303.

9. So HY, Li PK, Lai PB, et al. Hong Kong Academy of Medicine

position paper on postgraduate medical education 2023.

Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:448-52. Crossref

10. Torre DM, Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. Theoretical

considerations on programmatic assessment. Med Teach

2020;42:213-20. Crossref

11. van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW, Scheele F, Driessen EW,

Hodges B. The assessment of professional competence: building blocks for theory development. Best Pract Res

Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2010;24:703-19. Crossref

12. Frank JR, Karpinski J, Sherbino J, et al. Competence by

Design: a transformational national model of time-variable

competency-based postgraduate medical education.

Perspect Med Educ 2024;13:201-23. Crossref

13. van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW, Driessen EW,

Govaerts MJ, Heeneman S. Twelve tips for programmatic

assessment. Med Teach 2015;37:641-6. Crossref

14. van Tartwijk J, Driessen E. Portfolios for assessment and

learning: AMEE Guide No. 45. Med Teach 2009;31:790-801. Crossref

15. Bhanji F, Naik V, Skoll A, et al. Competence by Design: the

role of high-stakes examinations in a competence based

medical education system. Perspect Med Educ 2024;13:68-74. Crossref

16. Iobst WF, Holmboe ES. Programmatic assessment: the

secret sauce of effective CBME implementation. J Grad

Med Educ 2020;12:518-21. Crossref

17. Torre D, Rice NE, Ryan A, et al. Ottawa 2020 consensus

statements for programmatic assessment—2.

Implementation and practice. Med Teach 2021;43:1149-60. Crossref

18. So HY, Li PK, Cheng BC; Faculty Development

Workgroup, Hong Kong Jockey Club Innovative Learning

Centre for Medicine; Leung GK. Faculty development

for postgraduate medical education in Hong Kong. Hong

Kong Med J 2024;30:428-30. Crossref

19. Uijtdehaage S, Schuwirth LW. Assuring the quality of

programmatic assessment: moving beyond psychometrics.

Perspect Med Educ 2018;7:350-1. Crossref