Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 20 Jan 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Pneumonia-associated inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour: a case report

Xiuxin Mo1; Yuchun Zhuang1; Liming Zhang1; Chengcheng Chen2

1 Department of Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgery, Weifang Second People’s Hospital, Weifang, China

2 Department of Radiology, People’s Hospital of Rizhao, Rizhao, China

Corresponding author: Dr Chengcheng Chen (chengcheng9987@163.com)

Case presentation

A 42-year-old woman was admitted to Weifang

Second People’s Hospital on 20 June 2024 following

an incidental finding of a pulmonary nodule (21 × 27 mm2) during a routine physical examination 1

year previously. Although serial imaging over the

following year showed stable size and morphology,

suggesting a benign nature, malignancy remained

possible. The patient had no significant medical,

family, or psychosocial history, and denied tobacco

and alcohol use. Preoperative evaluation included

fine-needle aspiration cytology, which revealed

spindle cells with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration.

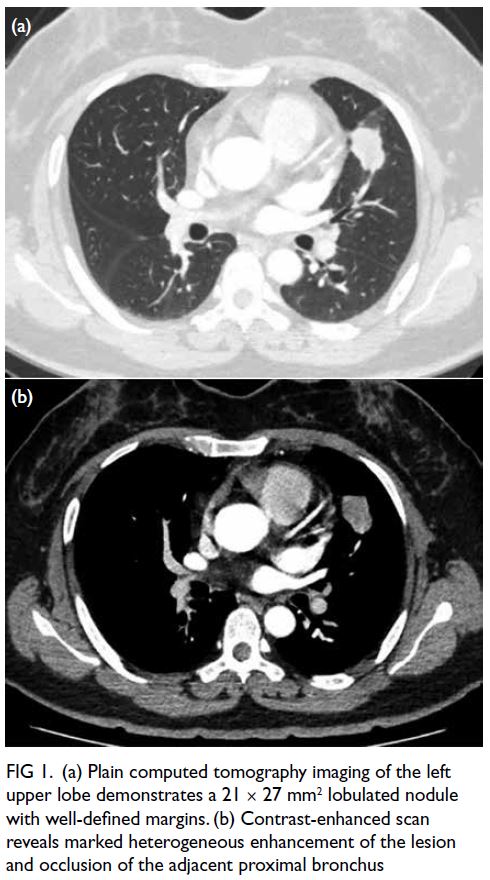

Contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography

demonstrated a lobulated left upper lobe nodule

with heterogeneous enhancement and partial

bronchial obstruction (Fig 1). Magnetic resonance

imaging of the brain and abdominal ultrasound

showed no metastasis. Based on the above

investigations and considering the patient’s financial

circumstances, a positron emission tomography

scan was not performed. Tumour marker levels

were within the normal range—neuron-specific

enolase: 13.06 ng/mL, carbohydrate antigen 19-9:

9.76 U/mL, carcinoembryonic antigen: 1.54 ng/mL,

cytokeratin 19 fragment: 1.23 ng/mL, and squamous

cell carcinoma antigen: 0.51 ng/mL. Thoracoscopic

left upper lobectomy was performed on 22 June

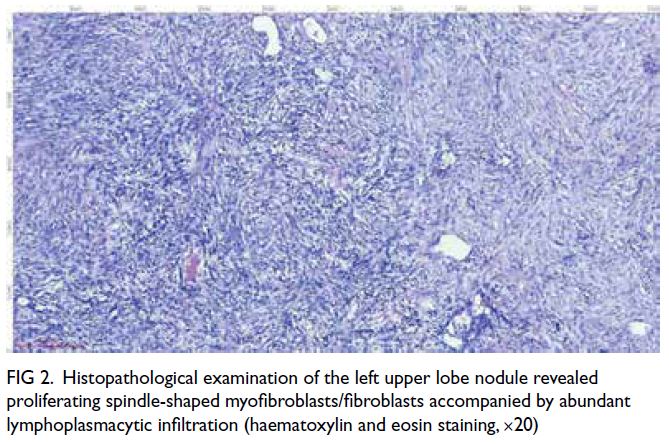

2024. Histopathology revealed proliferating spindle

myofibroblasts/fibroblasts with lymphoplasmacytic

infiltration and focal mucin deposition (Fig 2).

Immunohistochemistry confirmed inflammatory

myofibroblastic tumour (IMT): positive for

cytokeratin, vimentin, smooth muscle actin (SMA),

and epithelial membrane antigen; STAT6 (signal

transducer and activator of transcription 6) negative

with a Ki-67 index of 30%. The patient recovered

well, with no recurrence at 3-month follow-up,

although long-term surveillance was recommended.

Figure 1. (a) Plain computed tomography imaging of the left upper lobe demonstrates a 21 × 27 mm2 lobulated nodule with well-defined margins. (b) Contrast-enhanced scan reveals marked heterogeneous enhancement of the lesion and occlusion of the adjacent proximal bronchus

Figure 2. Histopathological examination of the left upper lobe nodule revealed proliferating spindle-shaped myofibroblasts/fibroblasts accompanied by abundant lymphoplasmacytic infiltration (haematoxylin and eosin staining, ×20)

Discussion

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour, originally

termed inflammatory pseudotumour (IPT) in

1939, has been reclassified through molecular

insights from a reactive proliferation to a true neoplasm.1 Although IPT remains a non-neoplastic

inflammatory lesion with regression potential, IMT

is now defined as a clonal neoplasm composed

of myofibroblastic spindle cells within a plasma

cell/lymphocyte/eosinophil-rich stroma. This

distinction is crucial clinically since IMT exhibits

local invasiveness and recurrence risk, unlike IPT’s

benign course.2

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour is a

rare mesenchymal neoplasm that primarily affects

children and young adults, with lower incidence

in adults.3 Its broad anatomical distribution

most commonly involves the lungs (0.7% of

pulmonary tumours)4 and the abdomen/mesentery/retroperitoneum; rare sites include the oesophagus,

cardiac chambers, and adrenal glands. As a

borderline malignancy, recurrence rates differ by

site (pulmonary 2% vs extrapulmonary 25%), with

less than 5% risk of distant metastasis.5 Symptoms

vary anatomically: pulmonary cases may present

with cough or haemoptysis (including incidental

detection), abdominal lesions may cause pain or

obstruction, while systemic symptoms include fever

and weight loss. Pulmonary IMTs, as observed in

our patient, may present with cough, atypical chest

pain, haemoptysis, or dyspnoea, although incidental

detection during routine health screening, as in our

case, is not uncommon.

The non-specific radiological features of IMT

pose significant diagnostic challenges, necessitating

histopathological confirmation. In our patient, the

nodule was identified during a routine physical

examination 1 year prior to admission, and serial

imaging demonstrated stable lesion size. This

supported a benign nature but did not entirely

exclude malignancy. Although minimally invasive

techniques such as fine-needle aspiration biopsy

and bronchoscopic sampling are often attempted,

these methods frequently yield insufficient

tissue for definitive diagnosis. Complete surgical

resection therefore remains the gold standard

for both diagnostic confirmation and therapeutic

intervention.

Histopathological examination typically reveals spindle-shaped myofibroblastic proliferation

within variable stromal matrices (myxoid,

collagenous, or calcified patterns), accompanied

by a polymorphic inflammatory infiltrate. In

our patient, the histopathological features were

consistent with IMT, showing proliferating spindle-shaped

myofibroblasts/fibroblasts with abundant

lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and focal mucin

deposition. The diagnosis was further supported by

immunohistochemical findings, including positivity

for cytokeratin, vimentin, SMA, and epithelial

membrane antigen, although anaplastic lymphoma

kinase (ALK) and STAT6 were negative.

Molecular studies have identified

chromosomal 2p23 translocations in approximately

50% of IMT cases, leading to constitutive activation

of ALK pathways.6 This genetic aberration

correlates with tumour aggressiveness and local

recurrence, supporting IMT’s classification as a

true neoplasm rather than a reactive pseudotumour.

Immunophenotypically, most IMTs express

mesenchymal markers such as ALK (cytoplasmic/membranous), caldesmon, desmin, and SMA,

with ALK reactivity aiding differentiation from

histological mimics. Notably, our case showed an

atypical immunoprofile with SMA positivity and ALK

negativity, reflecting the phenotypic heterogeneity

and the need for comprehensive molecular profiling

in challenging cases.

Therapeutic strategies for IMT depend on

disease stage and resectability. For localised lesions,

complete surgical resection (R0 margins) achieves a

2% recurrence rate, whereas incomplete resection

(R1/R2) increases recurrence risk to 60% (P<0.01).7

In our patient, thoracoscopic left upper lobectomy

was performed with negative surgical margins, and

no tumour recurrence was observed during the initial

3-month postoperative follow-up. Nonetheless,

longer-term surveillance is recommended to confirm

the absence of tumour recurrence. Non-resectable

or recurrent cases require multimodal approaches,

including radiotherapy (45-50 Gy), platinum-based

chemotherapy, and ALK inhibitors for ALK-positive

subtypes.

Emerging molecular insights have identified

ALK rearrangements as key oncogenic drivers,

positioning ALK-targeted therapies as both

diagnostic and therapeutic tools.8 Clinical trials have

demonstrated the efficacy of crizotinib: an initial

phase 1 study (NCT01121588)9 achieved a 42.9%

partial response rate in refractory paediatric/young

adult IMTs (n=7), while cohort expansion (n=14)

improved the overall response rate (ORR) to 86% (36%

complete responses). Japanese studies corroborate

these findings, with 100% ORR (1 complete response,

2 partial responses) in ALK-rearranged IMTs

treated with crizotinib or alectinib.10 Nonetheless,

therapeutic heterogeneity (ORR: 36%-100%), small sample sizes, and geographical bias necessitate

standardised multicentre trials to validate efficacy

and durability.

In summary, IMT represents a rare borderline

neoplasm with intermediate malignant potential,

distinct from the historically described IPT. The

present case highlights the importance of accurate

histopathological and immunohistochemical

diagnosis, particularly in immunophenotypically

atypical lesions, and underscores the need for long-term

follow-up to monitor for potential recurrence.

Author contributions

Concept or design: X Mo.

Acquisition of data: Y Zhuang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: L Zhang.

Drafting of the manuscript: X Mo.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: C Chen.

Acquisition of data: Y Zhuang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: L Zhang.

Drafting of the manuscript: X Mo.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: C Chen.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study was supported by the Science and Technology

Development Project of Weifang (Ref No.: 2024YX077) and

Weifang Youth Medical Talent Cultivation Support Program,

China. The funders had no role in the study design, data

collection/analysis/interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Weifang

Second People’s Hospital, China (Ref No.: KY2024-077-01)

and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki. The patient provided written informed consent for

participation and publication of this case report, including the

accompanying clinical images.

References

1. Höhne S, Milzsch M, Adams J, Kunze C, Finke R. Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT): a representative literature review occasioned by a rare IMT of the transverse colon in a 9-year-old child. Tumori 2015;101:249-56. Crossref

2. Sagar AE, Jimenez CA, Shannon VR. Clinical and histopathologic correlates and management strategies for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung. A case series and review of the literature. Med Oncol 2018;35:102. Crossref

3. Kiratli H, Uzun S, Varan A, Akyüz C, Orhan D.

Management of anaplastic lymphoma kinase positive

orbito-conjunctival inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

with crizotinib. J AAPOS 2016;20:260-3. Crossref

4. Surabhi VR, Chua S, Patel RP, Takahashi N, Lalwani N,

Prasad SR. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors: current

update. Radiol Clin North Am 2016;54:553-63. Crossref

5. Bedi D, Clark BZ, Carter GJ, et al. Prognostic significance

of three-tiered World Health Organization classification

of phyllodes tumor and correlation to Singapore General

Hospital nomogram. Am J Clin Pathol 2022;158:362-71. Crossref

6. Pacheco E, Llorente JL, López-Hernández A, et al. Absence

of chromosomal translocations and protein expression of

ALK in sinonasal adenocarcinomas [in English, Spanish].

Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2017;68:9-14. Crossref

7. Baldi GG, Brahmi M, Lo Vullo S, et al. The activity of

chemotherapy in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors: a

multicenter, European retrospective case series analysis.

Oncologist 2020;25:e1777-84. Crossref

8. Mossé YP, Lim MS, Voss SD, et al. Safety and activity of

crizotinib for paediatric patients with refractory solid

tumours or anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: a Children’s

Oncology Group phase 1 consortium study. Lancet Oncol

2013;14:472-80. Crossref

9. Antoniu SA. Crizotinib for EML4-ALK positive lung

adenocarcinoma: a hope for the advanced disease?

Evaluation of Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al.

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non–small-cell

lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363(18):1693-703. Expert

Opin Ther Targets 2011;15:351-3. Crossref

10. Takeyasu Y, Okuma HS, Kojima Y, et al. Impact of ALK

inhibitors in patients with ALK-rearranged nonlung solid

tumors. JCO Precis Oncol 2021;5:PO.20.00383. Crossref