© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

HEALTHCARE FOR SOCIETY

The Hong Kong Hospital Authority reform: a

historical perspective

Foreword

Fei-chau Pang, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Community Medicine)

President, Hong Kong College of Community Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

The Hong Kong College of Community Medicine

is pleased to present a special edition of a series of

articles written by Dr William Ho JP,1 our Honorary

Fellow and former Chief Executive of the Hong Kong

Hospital Authority (HA), on the HA’s early history

as well as his insightful reflections. More than three

decades have passed since the inception of the HA

in December 1990. At the time, the HA reform was

hailed as an unprecedented successful management

transformation exercise, galvanising the energy of

healthcare professionals to improve service quality

by leaps and bounds. Upon leaving the HA in 2005,

Dr Ho began writing about this part of Hong Kong’s

health system’s history, from the unique angle and

vantage point of a frontline clinician in the pre-HA

era, a doctors’ union leader involved in negotiations

with the Government during the transition period,

and subsequently as a medical administrator in

the newly formed HA, working all the way to the

top position of Chief Executive. His focus was not

so much on the detailed chronology of events,

but on the socio-economic, political, managerial

and philosophical underpinnings that shaped the

trajectory of the HA reform.

Today, the organisation is once again

approaching a critical point, facing challenges of

increasing demand, long waiting times, and staff

shortages. Last year, the Government called upon

the HA to conduct ‘a comprehensive review of

the systemic issues and the need for reform with

regard to the management of public hospitals.’2 It

is noteworthy that many of the problems currently

encountered are not dissimilar to those Dr Ho

described in the pre-HA era. Given the passage of

time and changes in the environment, many of the

original ideas and concepts should be reinstalled

in the organisation’s memory and laid down as

a foundation for future faculty development in

healthcare management. From the perspective of

our Administrative Medicine subspecialty, such

historical material is most valuable for sharing

and learning, particularly for Fellows in healthcare

leadership roles. We also believe it will have a wider impact on the medical community and even

the lay public. Hence, we have discussed with Dr

Ho, who has kindly reviewed and suitably revised

what he wrote back then, culminating in a trilogy

of articles for the Hong Kong Medical Journal. We

are also grateful to the journal’s Editorial Board for

facilitating the publication as a special series.

Part 1: From pre–Hospital

Authority era to establishment of the Hospital Authority

William SW Ho, FCSHK, FHKCCM

Hong Kong College of Community Medicine, Hong Kong SAR,

China

This article series, comprising three parts (Part 1 to

Part 3), attempts to describe and analyse the early

history of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority (HA)

reform, from its inception to around the year 2000.

The HA is a huge organisation, second only to

the Civil Service in staff size, shouldering the

lion’s share of healthcare services in Hong

Kong. The process of its establishment and the

extensive reforms of the public hospital system

were most transformational and quite unique in

the international scene. Apart from the dramatic

service improvements achieved, the underlying

management concepts, philosophy and methods

were exemplary. Yet, there appears to be little in-depth

study on this epic journey, either within or

outside the organisation. As time has passed and

circumstances have changed, there is a feeling of

‘lost organisational memory’ in how the HA came

about and the underlying spirit of its systems and

processes, as reflected to the author by executives

and clinicians.

Background to the reform

Public health services in the 1980s

Public health services in Hong Kong traditionally

were under the purview of the Health and Welfare

Branch of the Hong Kong Government Secretariat,

and provided through the Medical and Health

Department (M&HD). The Director of Medical

and Health Services was in charge of the public

health functions and operation of the Government hospitals. In 1985, 47% of all hospital beds were in

Government hospitals,3 while another 41% were in

Subvented hospitals4 run by charitable organisations

such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals,

Caritas Hong Kong, and so on. The remainder were

in private hospitals. While the parent organisations

of Subvented hospitals owned the land and buildings,

as well as managed these hospitals’ operations and

staff, the operating costs were increasingly subsidised

by the Government, hence the term ‘Subvented’. In

general, their hospital equipment, staff terms and

training opportunities were inferior compared with

Government hospitals. Public hospital services were

highly subsidised and fees were nominal compared

with the actual cost.

Health services provision in the late 1970s

and early 1980s generally followed the 1974 White

Paper of the Hong Kong Government entitled

The Further Development of Medical and Health

Services in Hong Kong. The main proposals included

organising services on a regional basis, building

new facilities to cater for the needs of the growing

population, particularly in new towns, to achieve a

target of 5.5 hospital beds per 1000 population, and

starting a new medical school, a new nursing school

and a dental school.5 By the mid-1980s, the system

was evidently not coping. One reason was the rapid

increase in the population, which grew by 24.18%

in the 10-year period after 1974, particularly due to

legal and illegal immigrants from Chinese Mainland,

and Vietnamese refugees.6 Serious overcrowding,

particularly in the Government hospitals, with the

infamous ‘camp beds’ lining hospital corridors, was a

public eye sore. Staff discontent, both in terms of the

poor working environment and low morale, resulted

not only in a brain drain to the lucrative private

sector, but also in waves of union actions.7

Vivid accounts of the public hospital scenes at

that time can be found in the book entitled Bedside

Manner: Hospitals and Health Care in Hong Kong by

Robin Hutcheon.8 Observations from people in the

system whom he interviewed could be summarised

as a severe lack of proper management in public

hospitals, poor quality of care, inefficiency in

using Subvented hospitals in the system, jealousy

over unequal staff terms, and hospital Medical

Superintendents being poorly trained for their jobs.8

Approach to the reform

International influence

It is to be noted that Hong Kong was not unique in

having a poorly run public healthcare service. In the

United Kingdom, the government-commissioned

Griffiths Report of 19839 severely criticised its

National Health Service (NHS), and recommended

wholesale management reform. This was quickly

embraced and implemented by the Thatcher government. The United Kingdom’s experience

then influenced other Commonwealth countries

such as Australia, New Zealand and Singapore,

where similar reforms were planned for their public

health systems. Indeed, managerial reform of public

entities to improve performance was the trend of the

period in many countries. This ranged from internal

management strengthening, corporatisation ‘hiving

off’ Civil Service functions to be run by corporate

entities, to outright privatisation. An example in

Hong Kong would be the formation of the Housing

Authority in 1973 to introduce professional housing

management.10

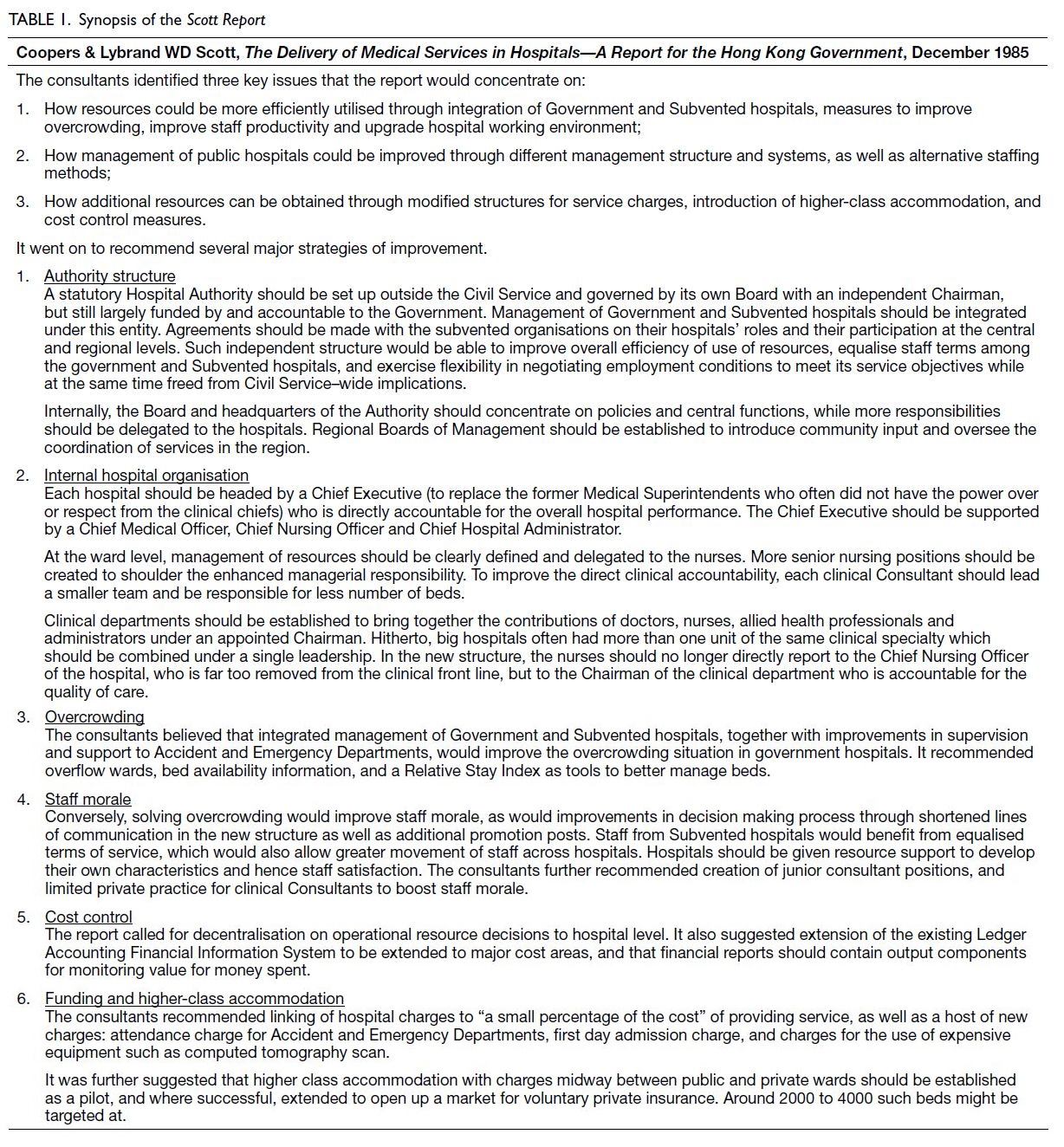

Consultancy study

Facing increasing public discontent over the quality

of the public hospital services, several legislators

pressed for change, including Dr Harry Fang 方心讓,

Dr Henrietta Ip 葉文慶, and Ms Lydia Dunn 鄧蓮如.

The Secretary for Health and Welfare Mr Henry

Ching 程慶禮 proposed calling in consultants to

conduct an overall review, which was approved by the

Executive Council. The job was eventually awarded

to Coopers & Lybrand, WD Scott from Australia,

who published their report in December 1985 (the

Scott Report) [Table 1]. A key recommendation

was to take the whole public hospital system away

from the M&HD, to be managed by an independent

Hospital Authority, free from the constraints of the

Civil Service.

At the outset, however, the consultancy study

was criticised for its limited scope, which even the

consultants themselves admitted in their report. As

the pressure at the time was over public hospital

services, the consultants’ brief was merely to look at

how the public hospital system could be improved.11

This approach of excluding the public health and

primary care sides of the healthcare system from the

reform proposal sowed the seed for eventual over-reliance

on hospital systems and fragmentation.

Such weakness was particularly felt much later

during the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)

epidemic of 2003 when coordination between the

hospital and public health sides was most vital for

the success of control.

Political process

Public and stakeholder consultation

The Government conducted public consultation on

the Scott Report in 1986. Public opinion welcomed

proposals on enhancing community participation

and the overall objective of management reform

in public hospitals, but vehemently objected to the

suggestion of linking service fees to a percentage

of the cost. Staff working in Subvented hospitals

welcomed the proposals, as they expected better

pay and a more equitable allocation of resources to their hospitals, even though the directors of the

parent organisations feared a loss of autonomy. Civil

Servants working in Government hospitals, however,

opposed to the proposal, which threatened to cut

their existing benefits in order to equalise terms

with Subvented hospital staff, and possibly reduce job stability compared with Civil Servants. Nursing

unions also opposed the proposed change that would

place nurses under the doctors’ management in the

new clinical departmental structure.

The OMELCO (Office of Members of the

Executive and Legislative Councils) Standing Panel on Health Services, as presented by the then medical

constituency representative Dr Hin-kwong Chiu

招顯洸 was generally in favour of the HA

proposal.12 The Governor-in-Council Sir David

Wilson 港督衛奕信 announced in his Policy Speech

on 7 October 1987 the decision to proceed with the

establishment of an HA to integrate the management

of all Government and Subvented hospitals into

a single system, and to introduce the necessary

management reform. To prepare for the change, the

original M&HD was to be split into a Department

of Health and a Hospital Services Department.

The latter would eventually be abolished upon the

management takeover by the HA. Meanwhile, a

Provisional Hospital Authority (PHA) was to be set

up to plan and prepare for the establishment of the

HA.

A historical twist

Meanwhile, the public hospital system continued

to deteriorate with severe overcrowding, poor

environment, long queues, and overworked staff with

low morale. The exodus of doctors into the private

sector reached a historical high of around 13% for

Government hospitals and exceeded 20% for some

Subvented hospitals in 1988. Sentiments among

members of the Government Doctors’ Association

(GDA)13 culminated in a call for industrial action,

which was echoed by the The Joint Council of

Subvented Hospitals of Hong Kong, and nursing

unions. The plight of overworked doctors gained

the support of some legislators, such as Dr Che-hung

Leong 梁智鴻 and Mr Martin Lee 李柱銘.14

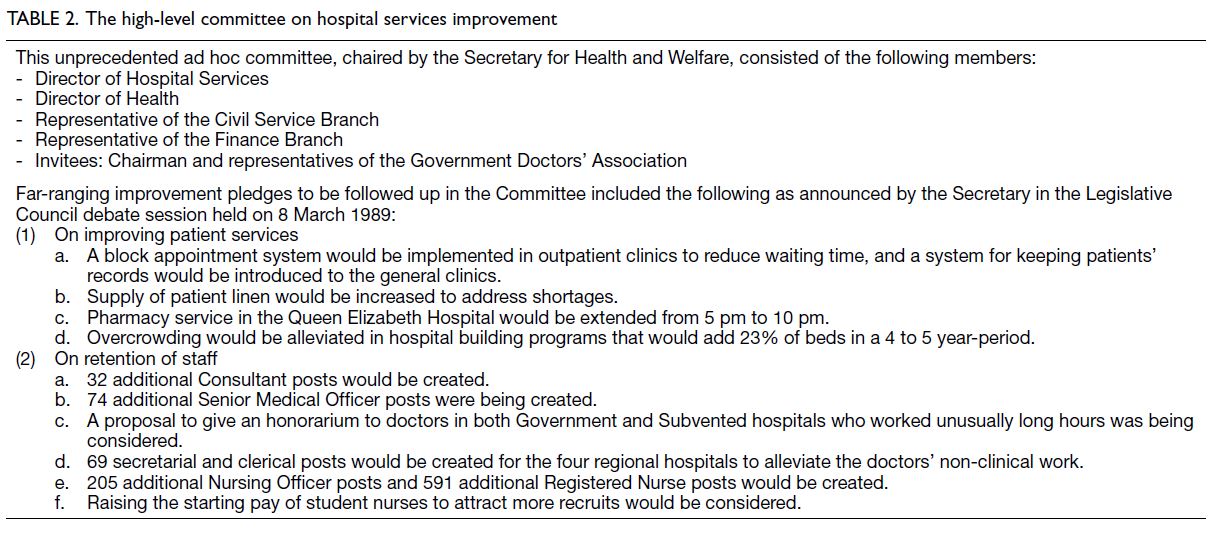

In a symbolic strike that lasted for 10 days from 1 March 1989,15 the GDA was able to win over

public sympathy and succeeded in pressing the

Government to agree to their demand for setting up

a high-level committee, comprising representatives

of relevant Government branches and departments,

as well as GDA representatives. Chaired by the then

Secretary for Health and Welfare Mr Brian Tak-hay

Chau 周德熙, the committee provided a platform for

negotiation and for monitoring progress on promised

improvements, without deferring to the yet-to-be-established

HA. These included plans to eliminate

camp beds, reduce patients’ waiting times in

specialist clinics, improve linen supply for patients,

as well as significantly enhance the salary structure

and promotion opportunities for both doctors and

nurses. The scale of these improvements within such

a short time was unprecedented in the history of the

M&HD (Table 2).

From Provisional Hospital Authority to

Hospital Authority

The PHA was established on 1 October 1988,

chaired by Sir Sze-yuen Chung 鍾士元爵士, a

veteran Executive and Legislative Councillor. The

PHA adopted most of the recommendations of

the Scott Report and developed detailed plans.

The Government published the PHA Report on

1 April 1990. Legislative processes ensued, and

the HA Ordinance was enacted on 1 December

1990, when the HA was formally established, with

Sir Sze-yuen Chung at the helm. Most proposed

changes were planned for phased implementation,

except the proposal to link fees and charges to costs.

Indeed, it was written into the HA Ordinance: “the principle that no person should be prevented, through lack of means, from obtaining adequate medical treatment”.16

Negotiations with the Government on funding

and administrative arrangements turned out to

be complex, as more than 20 other Government

departments had previously served the public

hospitals as part and parcel of their work. Examples

included the Architectural Services Department

looking after hospital buildings and capital projects;

the Electrical and Mechanical Services Department

overseeing building services and hospital equipment;

the Government Supplies Department handling

procurement and inventories; and the Department

of Health with its intricate involvement in hospital

operations. Once the HA was established, however,

it was envisaged that either the HA would have to

take over the work or be cross-charged.

Another dimension was the additional resources

incurred simply because the HA became a separate

legal entity. In the past, Government departments

were deemed exempt from many pieces of legislation.

However, the HA would not enjoy such exemptions

and would incur additional resources to comply with

the myriad requirements of various ordinances. The

Government agreed to allocate additional resources

for the HA to purchase necessary insurance policies,

licences and registration fees. Nevertheless, the full

implications of these requirements could not be

easily appreciated from day one.17

There were also negotiations with staff unions

on new HA terms of employment and ‘bridging-over

terms’, as well as with the boards of directors

of Subvented hospitals, which proceeded in earnest.

For the latter, it was agreed that ownership of land,

properties, and equipment would continue to

belong to the parent organisations, including any

subsequent Government investment in hardware

upgrades. It was also agreed that nominations from

the parent bodies would constitute the majority in

future Hospital Governing Committees.18 Formal

contract signing with all 15 Subvented organisations

that governed 23 hospitals in the system took place

on 24 May 1991.19 In a ‘big bang’ approach, the HA

took over the management of all 38 public hospitals

and 37 000 staff overnight on 1 December 1991.20

Thus, it took merely around 6 years from the

conception of an independent HA, to 1 December

1990, when the HA was formally established,

and another 12 months for the HA to take over

all operations of public hospitals. Given the scale

of public hospital services and the enormity of

major changes to be implemented, this was a most

successful feat, even by international standards.

Such a result could be attributed to congruence with

prevailing societal values and concerns, as well as

major stakeholders’ interests. An attempt to explain

these factors is made below.

Analysis

Societal value system

Hong Kong as a predominantly Chinese society

first and foremost embodied the traditional values

of communitarianism and the Confucian care-based

ideology of good government, particularly

in healthcare.21 At the same time, Hong Kong, as a

British colony for more than a century, had inherited

much of the British system in its social structure.

The public healthcare system was similar to the

British NHS, with centralised bureaucratic control,

funded entirely through general taxation, and with

all doctors employed as salaried staff. The ideology

was similarly one of egalitarianism, where the

stated Government policy was that every citizen

had the right to appropriate public healthcare when

sick. This spirit was eventually written into law, as

mentioned above, namely “no person should be

prevented, through lack of means, from obtaining

adequate medical treatment”.16

However, unlike the NHS with its framework

of General Practitioner gatekeeping, Hong Kong

did not have a well-developed public primary care

system. Instead, there existed a large private sector

in which patients typically paid out of pocket for

treatment. Under such a ‘dual system’, people could

afford private care for minor illnesses, while most

depended on the public system for hospital services.

Such a value system explains:

a. The vehement community opposition to even

a hint of linking public hospital charges to a

percentage of the cost.

b. The relative tolerance of the Government’s

decision to focus reform efforts solely on public

hospitals, rather than clinics, even though no

one would consider the services in Government

General Out-Patient Clinics to be any better.

c. The general sympathy for overworked hospital

staff, given that patients’ lives were at stake.

Stakeholders' interests

Any major reform has to address the interests of key

societal stakeholders. The state of affairs at the time

can be summarised as follows:

a. Public: While the majority of patients with severe

illnesses depended on the public sector for the

highly subsidised care, there was widespread

discontent over the poor state of public hospitals

in the early 1980s. Change for the better was, in

fact, long overdue.

b. Staff: Doctors and nurses in the system were

increasingly frustrated by overcrowding and

poor working environment. They deeply felt

the constraints of stifling bureaucracies, where

obvious problems were left unaddressed.

Manpower shortages worsened as experienced

staff left for the private sector in growing numbers.

c. Government: There was evidence that the

Government was equally concerned about

system-wide inefficiencies and the limited

management capabilities in the M&HD. At

the same time, while the Government was

increasingly funding the Subvented hospitals,

it felt it lacked a commensurate level of control

over their operations.

d. Subvented organisations: There was a strong

sense of second-class treatment among

Subvented hospitals, particularly in terms of staff

conditions, equipment, and funding compared

to Government hospitals. Any reform aimed at

levelling these disparities would be welcomed.

Although the respective boards of directors

feared losing autonomy under the new HA, such

concerns were outweighed by overwhelming staff

support for change.

e. Politicians: The interests of Legislative

Councillors largely coincided with those of

the public. Moreover, there were ‘functional

constituency’ legislators at the time, including

one seat for the Medical constituency (elected

by registered medical practitioners) and another

for the Health constituency (elected by other

healthcare professionals). There were also

appointed members with medical backgrounds.

Their expertise in the healthcare field often gave

them considerable influence in related debates.

f. Professional bodies: The Hong Kong Medical

Association was all along supportive of public

hospital reform, in light of the plight of public

doctors who formed a considerable part of its

membership.22 The same applied to nurses’

unions, particularly The Hong Kong Association

of Nursing Staff and the Nurses Branch of the

Hong Kong Chinese Civil Servants’ Association,

as well as other bodies such as the Association of

Hospital Administrators, Hong Kong.

g. Business sector: The business sector generally

welcomed any Government initiative to improve

public hospital services, viewing it as beneficial

for societal stability, economic development and

the health of the workforce. Moreover, a high-quality,

heavily subsidised public hospital service

would also indirectly benefit private businesses

by helping lower the premium of health insurance

they needed to provide for employees.

h. Private hospitals: Private hospitals only

constituted a small portion of the market share

for hospital services, as most people could not

afford private care and fewer than half of the

population had any meaningful private health

insurance cover at the time. These hospitals also

operated as separate entities without a united

front and thus did not exert much political

influence.23

Epilogue

As described above, the 6 years from the initial

conception to the formal establishment of the HA

were by no means straightforward and guaranteed.

Political determination by the Government was

paramount, while leadership from legislators,

community organisations and staff bodies was

also instrumental. Equally important, the buoyant

economy of Hong Kong at the time helped support

such bold reform, which predictably had major

resource implications. Be that as it may, this was only

the first step in the journey. Part 2 will describe how

the HA undertook the mammoth task of reforming

the public hospital system in its initial years, based

on the blueprint established thus far.

Declaration

The author declares full responsibility for the accuracy of the

content, which does not represent the views of the Hospital

Authority. Given the scale of the reform, not all aspects can

be covered in detail. Interested readers and scholars are

encouraged to consult the Hospital Authority’s publications

for further information.

Acknowledgement

This article series is based on an unfinished project from

the author’s time as a visiting fellow at the Harvard School

of Public Health, aiming to document both the history

and philosophy of the reform. The author is grateful to

two successive Presidents of the Hong Kong College of

Community Medicine, Dr Libby Lee and Dr Fei-chau Pang,

for encouraging its revival.

Notes

- The author was Chief Executive of the HA from 1999 to 2005. He was initially trained as a specialist in general surgery and worked in the former M&HD. Upon the establishment of the HA in 1991, he joined the HA Head Office to assist in the management transformation process, and thereafter worked in the operations team in various positions. He was appointed Hospital Chief Executive of Kwong Wah Hospital from 1995 to 1999, before being further promoted to head the entire organisation as Chief Executive.

- Hong Kong SAR Government. Secretary for Health deeply concerned about management of public healthcare system [press release]. 21 Jun 2024. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202406/21/P2024062100808.htm. Accessed 1 Sep 2025.

- Coopers & Lybrand WD Scott. The Delivery of Medical Services in Hospitals—A Report for the Hong Kong Government. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer; December 1985. Section 3.1.

- These hospitals, originally established as private institutions, became increasingly dependent on Government subvention for financial sustainability over time, hence the term ‘Subvented hospitals’.

- Coopers & Lybrand WD Scott. The Delivery of Medical Services in Hospitals—A Report for the Hong Kong Government. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer; December 1985. Appendix 3A.

- Coopers & Lybrand WD Scott. The Delivery of Medical Services in Hospitals—A Report for the Hong Kong Government. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer; December 1985. Appendix 3B.

- Ng A. Medical and health. In: Tsim TL, Luk BH, editors. The Other Hong Kong Report. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 1989.

- Hutcheon R. Bedside Manner: Hospital and Health Care in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 1999: 34-42.

- National Health Service Management Inquiry. Griffiths Report. London: Department of Health and Social Security; 1983.

- Hutcheon R. Bedside Manner: Hospital and Health Care in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 1999.

- Coopers & Lybrand WD Scott. The Delivery of Medical Services in Hospitals—A Report for the Hong Kong Government. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer; December 1985. Section 1.1.

- Official Report of Proceedings of the Hong Kong Legislative Council. Session held on 15 October 1986. Hong Kong: Legislative Council; 1986.

- The author was Vice Chairman of the Government Doctors’ Association in 1989 and actively took part in negotiations with the Government. He became Chairman in 1990-1991.

- Official Report of Proceedings of the Hong Kong Legislative Council. Session held on 8 March 1989. Hong Kong: Legislative Council; 1989.

- The main action that achieved the aim of embarrassing the Government without adversely affecting patient care was the refusal of public doctors to sign the payment slips for discharged patients, who were discharged anyway but without the need to pay up. The other actions—refusing to teach nursing students, attend non-urgent medical boards, and write non-urgent medical reports “because the doctors were too busy”—were essentially cosmetic, with little real impact during the short period.

- Hong Kong SAR Government. Hospital Authority Ordinance (Cap 113), Section 4(d). Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Printer; 1990.

- Indeed, the HA was haunted years later by stipulations in the Employment Ordinance that certain staff unions claimed the organisation had violated, due to the long working hours of doctors—the subject of a lawsuit that lingered until 2006 over matters dating back to before 2000.

- The HA also promised to honour the traditions and philosophies of the parent organisations. Examples included service restrictions (such as abortion) in some religious hospitals, and the traditional Free Medical Service provided by the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGHs) for out-patients. With these concessions, the HA was able to reach agreement first with the TWGHs, which owned five hospitals. Once this was accomplished, the other subvented organisations soon followed suit.

- Following enactment of the HA Ordinance, these hospitals became known as Schedule 2 hospitals. Schedule 1 hospitals comprised all former Government hospitals previously under M&HD.

- Such a feat was rarely seen elsewhere. Singapore, for example, reformed its public hospitals one at a time.

- Tao J. Confucian care-based philosophical foundation of health care, In: Leung GM, Bacon-Shone J, editors. Hong Kong’s Health System: Reflections, Perspectives and Visions. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2006: 41-60.

- The Association’s stance changed considerably a few years later, due to concerns that a “too successful” HA posed a threat to the business of its private sector members. It complained of an “unequal playing field” as the HA was able to offer services that were equal to, if not better than, those of the private sector, while being heavily subsidised by the Government. However, this was not foreseen at the time.

- The Hong Kong Private Hospitals Association was not established until as late as 2000.