Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 5 Dec 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Van der Woude syndrome with novel variants: a case series

LT Leung, MB, ChB; Stephanie KL Ho, MB, BS; WC Yiu, MSc; Min Ou, MPhil; Jennifer YY Poon, MB, ChB; Shirley SW Cheng, MB, ChB; Ivan FM Lo, MB, ChB; HM Luk, MD (HK)

Department of Clinical Genetics, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

# Equal contribution

Corresponding author: Dr HM Luk (lukhm@ha.org.hk)

Case presentations

In January 2024, individuals presenting to the

Department of Clinical Genetics at Hong Kong

Children’s Hospital with suspected pathogenic

variants in the IRF6 or GRHL3 genes were assessed.

Eight patients with molecularly confirmed Van

der Woude syndrome (VWS) from four unrelated

families were identified, aged between 17 and 58

years, with a male-to-female ratio of 5:3. All four

index cases had an affected parent. Pedigrees of the

four families are shown in online supplementary Figure 1.

Cleft palate was observed in 75% (n=6) of

individuals, of whom two had bilateral cleft palate

and two had submucous cleft palate. Lower lip pits

were present in 62.5% (n=5). Cleft lip and/or alveolus

was evident in four patients (50%), usually affecting

both sides. Bifid uvula was observed in only one

individual, while hypodontia was seen in two. One

patient had ankyloglossia and two patients (25%)

developed vitiligo.

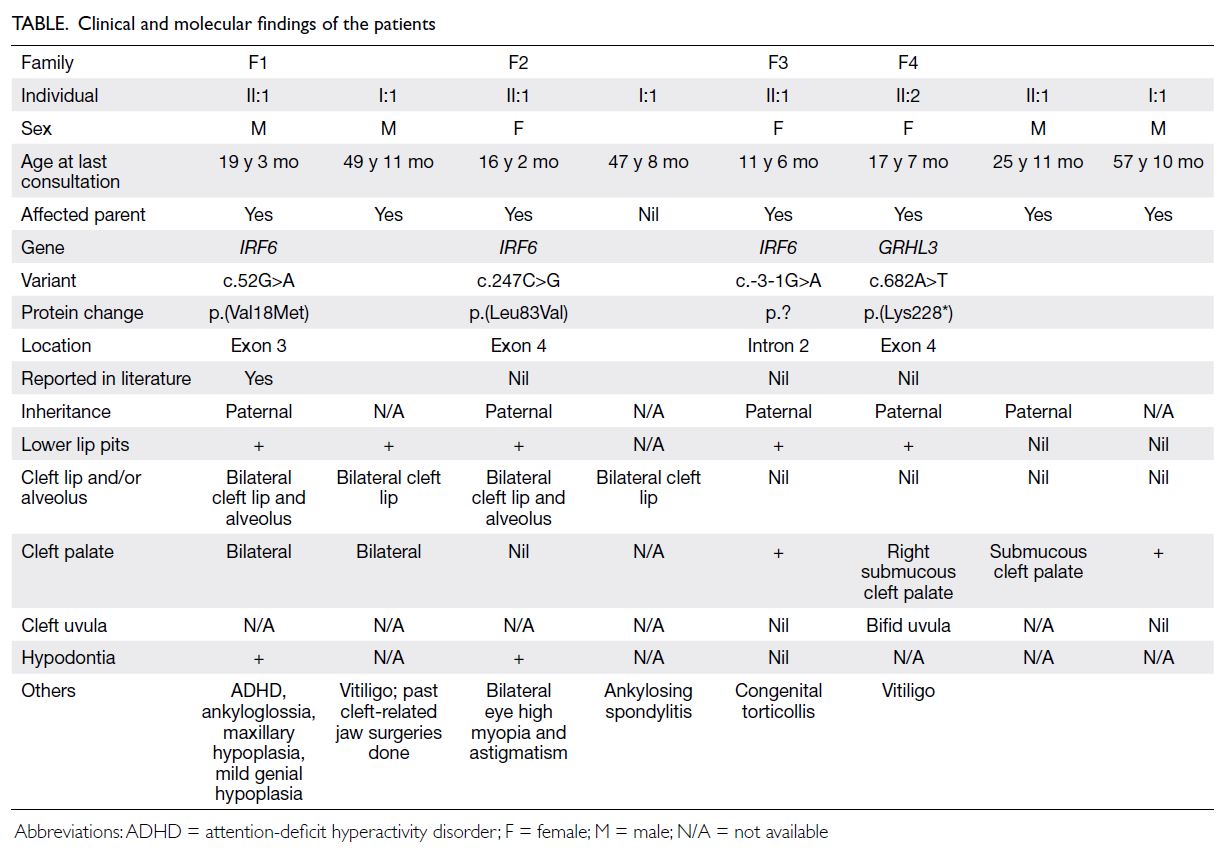

The clinical findings are summarised in the

Table. Clinical photos demonstrating oral findings

from Family 4 are shown in the Figure.

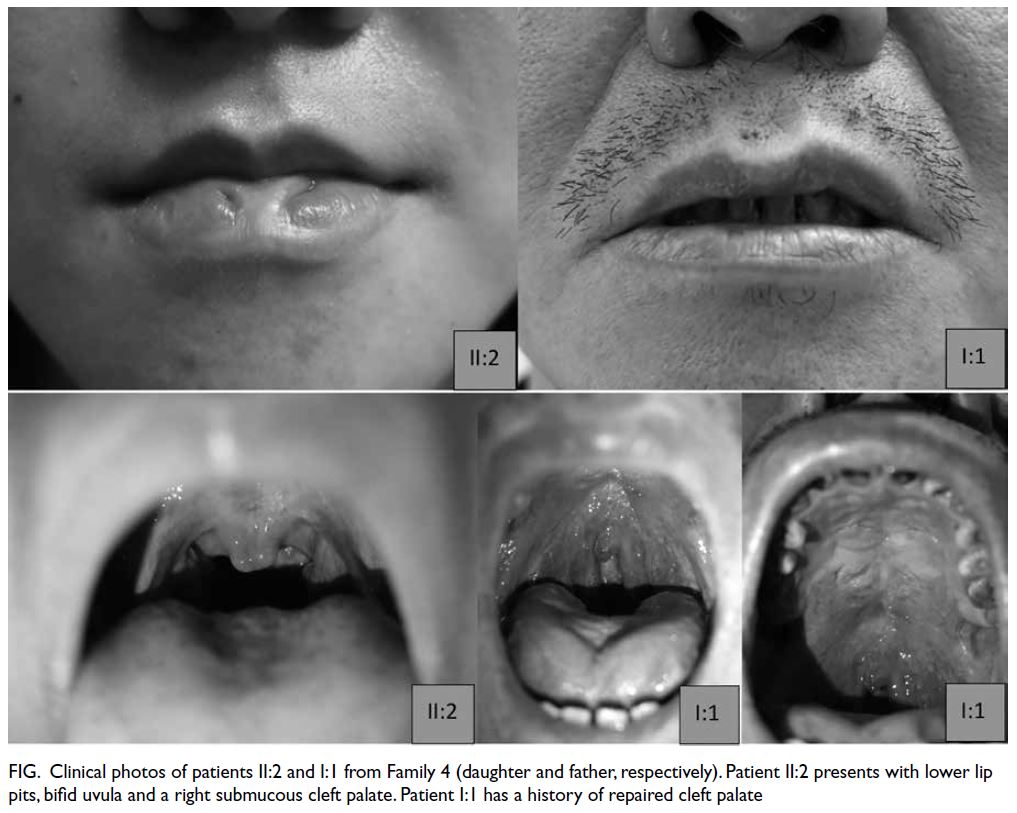

Figure. Clinical photos of patients II:2 and I:1 from Family 4 (daughter and father, respectively). Patient II:2 presents with lower lip pits, bifid uvula and a right submucous cleft palate. Patient I:1 has a history of repaired cleft palate

A different variant was identified in each of the

index patients in our cohort. Three harboured an IRF6

(NM_006147.4) variant, while the remaining index

patient had a variant in GRHL3 (NM_198173.3).

All variants were classified as likely pathogenic or

pathogenic according to the American College of

Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines1. Two

of the IRF6 variants were missense variants, while

the remaining one was a splice site variant. The

only GRHL3 variant identified in our cohort was a

nonsense variant. All other variants in our cohort

were novel, except IRF6 c.52G>A p.(Val18Met)

which has been previously reported.2

The molecular findings of our patients are

summarised in the Table and online supplementary Figure 2.

Discussion

Orofacial cleft is a prevalent congenital defect with an estimated global occurrence of 1 in 500 to 1000 births and a comparatively higher incidence in

Asia according to 2019 Global Burden of Disease

data3. It is linked to both environmental and

genetic factors. Most cases are non-syndromic,

presenting a reduced risk of a genetic disorder, with

orofacial clefts manifesting as isolated structural

anomalies. Nevertheless, syndromic cases comprise

approximately 30% of all cases, with an associated

higher risk in patients with central cleft lip and/or

palate (CL/P) or isolated cleft palate.4 Cases may be

familial or non-familial. According to a local study,4

the diagnostic yield of genomic variants, including

variants of uncertain significance, for non-syndromic

orofacial clefts was only about 4%. In contrast, for

syndromic cases, the detection rate of genomic

variants is as high as around 70%. Among these,

most variants have been detected by karyotyping or

chromosomal microarray.5 In view of this finding,

genetic testing (ie, chromosomal microarray) is

conventionally offered as first-line screening in

patients with syndromic orofacial clefts. Whole

exome sequencing is less commonly performed in

Hong Kong’s public clinical sector, although there is

no international consensus. Clinical and molecular

findings from our four families with VWS suggest

that whole exome sequencing may be helpful in

making a genetic diagnosis in patients with orofacial

clefts. This is advantageous for both the patient

and their family, as reproductive options such

as preimplantation genetic diagnosis or prenatal

diagnosis can be provided for at-risk individuals.

Van der Woude syndrome has historically been

linked to pathogenic variants in IRF6, which encodes a

transcription factor essential for the differentiation of

skin, as well as breast and oral epithelium. Abnormal

differentiation of the epidermis or oral periderm

may be implicated in the pathogenesis of CL/P.

The subsequent increase in the number of patients

with CL/P has been accompanied by the discovery

of a second gene, GRHL3. In vivo studies have

demonstrated that GRHL3 regulates the epidermal

permeability barrier through action downstream

of IRF6, explaining the phenotypic convergence.6

Although it has been postulated that GRHL3 is

more likely associated with cleft palate and less likely with cleft lip, CL/P and lip pits, the number of

affected patients remains too small to draw definitive

conclusions about genotype-phenotype correlations.

In our cohort, all three individuals with a GRHL3

variant had cleft palate (mostly submucous), no cleft

lip, and only one had lower lip pits. These findings

appear to align with previous reports.2 4 5

According to the literature, approximately 60%

of VWS cases show familial occurrence.7 All index

individuals in our cohort had an affected parent.

The concurrence of lower lip pits and CL/P has

been reported as the most common clinical features

among patients with VWS, affecting 80% of cases.8

In total, 75% and 62.5% of our patients had cleft

palate or lower lip pits, respectively. Cleft lip and/or alveolus was evident in 50% of individuals. These

findings are comparable with figures described in

previous studies.2 4 5 Disease-causing variants in

both genes have also been associated with dental

anomalies, including hypodontia, dental aplasia,

and malocclusion. Bifid uvula, hypodontia and

ankyloglossia were also observed in our cohort. It

is known that individuals with VWS exhibit highly

variable expressivity, ranging from isolated lower lip pits to bilateral CL/P. As highlighted by Family

4 in our cohort, lower lip pits were identified only

in individual II:2, but not in her elder sibling (II:1)

or father (I:1). This again demonstrates the broad

intrafamilial variability.

An enriched prevalence of vitiligo was also

observed in our cohort. Although not previously

reported in patients with VWS, two patients (one

harbouring an IRF6 and one a GRHL3 variant) in

our cohort had vitiligo. In individual F1 I:1, vitiligo

was diagnosed during adulthood; in individual F4

II:2, at 16 years of age. Our observation points to

a possible disease association, with the argument

that interferon regulatory factors play a significant

role in the immune system by functioning as major

transcriptional regulators of type I interferon.9 Further

research has revealed that IRF6 regulates a subset of

toll-like receptor 3 responses in human keratinocytes

and may play a role in keratinocyte and/or immune

cell functions during cell damage and wound healing.

Alternatively, GRHL3 is a transcription factor critical

for epidermal differentiation and skin barrier repair.

A possible association of dysfunction in interferon

regulatory factors or GRHL3 with autoimmune dermatological conditions such as vitiligo cannot be

excluded. Further studies are required to confirm a

potential correlation.

All IRF6 and GRHL3 variants found in our

cohort, except one, were novel. In previous VWS

reports, missense variants in IRF6 were mainly

clustered in exons 3, 4, 7, and 9, whereas truncating

variants were evenly distributed across the whole

gene.10 One novel IRF6 variant in our cohort was

a missense variant in exon 4, while another was a

splice site variant in intron 2. No specific genotype-phenotype

correlation was established in our current

study due to the limited sample size.

Due to the highly variable expressivity and

incomplete penetrance, it is essential for clinicians

to remain vigilant in diagnosing individuals with

a relatively mild phenotype. Referral to clinical

geneticists for consideration of genetic testing is

beneficial for affected individuals with familial

occurrence of CL/P or when other features suggest a

syndromic diagnosis. In view of the limited number

of individuals identified in our cohort, future studies

may be needed to establish clearer genotype-phenotype genotypephenotype

correlations, explore a potential

association with vitiligo, and evaluate the diagnostic

efficacy of whole exome sequencing.

Author contributions

Concept or design: LT Leung, SKL Ho.

Acquisition of data: WC Yiu, M Ou, JYY Poon, SSW Cheng, IFM Lo, HM Luk.

Analysis or interpretation of data: LT Leung, SKL Ho, WC Yiu.

Drafting of the manuscript: LT Leung, SKL Ho, IFM Lo, HM Luk.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: IFM Lo, HM Luk.

Acquisition of data: WC Yiu, M Ou, JYY Poon, SSW Cheng, IFM Lo, HM Luk.

Analysis or interpretation of data: LT Leung, SKL Ho, WC Yiu.

Drafting of the manuscript: LT Leung, SKL Ho, IFM Lo, HM Luk.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: IFM Lo, HM Luk.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the patients and their family for their support.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency

in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki. The patients/their legal guardian provided written

informed consent for participation and publication of this

case report.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors

and some information may not have been peer reviewed.

Accepted supplementary material will be published as

submitted by the authors, without any editing or formatting.

Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those

of the author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong

Academy of Medicine or the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J,

Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K.

Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of

sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of

the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in

medicine. 2015 May;17(5):405-23. Crossref

2. Kondo S, Schutte BC, Richardson RJ, et al. Mutations

in IRF6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes. Nat Genet 2002;32:285-9. Crossref

3. Wang D, Zhang B, Zhang Q, Wu Y. Global, regional and

national burden of orofacial clefts from 1990 to 2019:

an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Annals of Medicine. 2023 Dec 12;55(1):2215540. Crossref

4. Chan KW, Lee KH, Pang KK, Mou JW, Tam YH. Clinical

characteristics of children with orofacial cleft in a

tertially centre in Hong Kong. HK J Paediatr (new series)

2013;18:147-51.

5. Li YY, Tse WT, Kong CW, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and

pregnancy outcomes of fetuses with orofacial cleft: a

retrospective cohort study in two centres in Hong Kong.

Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2024;61:391-9. Crossref

6. De La Garza G, Schleiffarth JR, Dunnwald M, Mankad A,

Weirather JL, Bonde G, Butcher S, Mansour TA, Kousa YA,

Fukazawa CF, Houston DW. Interferon regulatory factor

6 promotes differentiation of the periderm by activating

expression of Grainyhead-like 3. Journal of investigative

dermatology. 2013 Jan 1;133(1):68-77. Crossref

7. Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Van der Woude

Syndrome [Internet]. Philadelphia: CHOP; 2024 Mar 31

[cited 2025 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/van-der-woude-syndrome

8. Hersh JH, Verdi GD. Natal teeth in monozygotic twins

with Van der Woude syndrome. Cleft Palate Craniofac J

1992;29:279-81. Crossref

9. Honda K, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. Type I interferon

[corrected] gene induction by the interferon regulatory

factor family of transcription factors. Immunity

2006;25:349-60. Crossref

10. Leslie EJ, Standley J, Compton J, Bale S, Schutte BC,

Murray JC. Comparative analysis of IRF6 variants in

families with Van der Woude syndrome and popliteal

pterygium syndrome using public whole-exome databases.

Genetics in Medicine. 2013 May;15(5):338-44. Crossref