Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 19 Sep 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Clinical and imaging patterns of child abuse in Hong Kong: a 10-year review from a tertiary centre

Catherine YM Young, MB, BS, FRCR1; CH Yiu1; Kathleen CH Tsoi, MB, ChB, MRCPCH2; Dorothy FY Chan, MB, ChB, FRCPCH2; Ki Wang, MB, BS, FRCR1; Winnie CW Chu, MB, ChB, MD1

1 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Paediatrics, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Catherine YM Young (youngymc@connect.hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Child abuse, a pressing medical and

social issue in Hong Kong, requires high vigilance

for prompt identification and early management.

The Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse Ordinance

has recently been gazetted, establishing a mandatory

obligation for suspected injury reporting to protect

children’s rights. This study aimed to describe the

incidence and patterns of child abuse in Hong Kong

to draw attention to this key issue.

Methods: A retrospective review of all reported child

abuse cases admitted to Prince of Wales Hospital

over a 10-year period (2014-2023) was performed.

Results: In total, 503 cases of child abuse were

retrieved from the hospital’s electronic system,

revealing an increasing trend over the years. Of

these cases, 341 cases (67.8%) were attributed to

physical abuse. Most cases involved trivial soft

tissue injuries, apart from two limb fracture cases,

which represented 0.4% of all reported child abuse

cases (n=503) and 0.6% of all reported physical child

abuse cases (n=341). Abusive head trauma (n=3)

constituted 0.6% of all reported physical child abuse

cases and 0.9% of all reported child abuse cases.

Two cases of severe abusive head trauma required

paediatric intensive care, and one case warranting neurosurgical intervention subsequently exhibited

gross motor delay.

Conclusion: Most child abuse cases in Hong Kong

present with minor clinical manifestations. Imaging

evidence of skeletal or neurological injury is present

in a small proportion of patients. Abusive head injury

is uncommon but carries far-reaching consequences;

early recognition is essential to protect affected

children from further harm. Paediatric radiologists

play a pivotal role in making the diagnosis.

New knowledge added by this study

- Fractures resulting from non-accidental injury are less common in Hong Kong, which has a predominantly Chinese population, than in Western countries; the fracture patterns differ.

- The overall incidence of abusive head trauma is low; however, a substantial proportion of patients with non-accidental injury who undergo further neuroimaging display positive findings.

- Interpretation of plain radiographs in cases of non-accidental injury should not solely rely on classical textbook fracture patterns; correlations with a compatible clinical history are particularly important.

- Neuroimaging is essential for children under 1 year of age with clinical suspicion of non-accidental injury, particularly those showing abnormal neurological signs, to detect abusive head trauma.

Introduction

Child abuse is a prevalent yet frequently overlooked

condition in paediatric patients worldwide, affecting

between 4% and 16% of the paediatric population.1

It may manifest as physical abuse, neglect, sexual

abuse, or psychological abuse,2 all of which carry

substantial long-term medical and psychological

consequences. Clinical presentation is often vague,

requiring a high degree of clinical suspicion by both clinicians and radiologists to ensure early activation

of child protection services. Multidisciplinary input

is needed for timely intervention and prevention of

recurrence.

While clinical evaluation is crucial for

identifying apparent or superficial injuries,

radiological imaging also plays a vital role in detecting

old or clinically occult injuries. John Caffey, a

paediatric radiologist, was among the first to describe the association between long bone fractures and

chronic subdural haematoma in infants, introducing

the concept of non-accidental injury.3 Since then, a

growing body of literature has emerged concerning

the radiological features of non-accidental injury,

contributing to increased global awareness. Various

guidelines have also been developed, including

those by The Royal College of Radiologists4 and the

American College of Radiology,5 which recommend

appropriate imaging modalities in suspected cases to

protect children’s welfare while balancing the risks of

radiation exposure.

Various retrospective studies in Western

populations have examined the epidemiology, injury

patterns, and outcomes of non-accidental paediatric

injuries in their respective regions6 7 8 9; however,

limited research has been conducted in Asia,

particularly within Hong Kong. This study aimed to

describe the incidence, clinical presentation, imaging

features, and treatment outcomes of child abuse in

a tertiary regional hospital in Hong Kong, with the

goal of raising awareness towards this commonly

overlooked condition.

Methods

This retrospective study included all reported cases

of child abuse involving paediatric patients (aged

0-18 years) admitted to Prince of Wales Hospital,

a tertiary regional hospital in Hong Kong, over a 10-year period (from January 2014 to December

2023). All suspected or confirmed cases of child

abuse were identified from the Clinical Data Analysis

and Reporting System, an electronic health registry

managed by the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong.

The search utilised key terms under the International

Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision coding,

including “Child maltreatment syndrome”, “Child

and adult battering and other maltreatment”, “Child

abuse”, and “Child maltreatment syndrome, shaken

infant syndrome”. Clinical records of all reported

cases were reviewed. Cases were excluded if they

were inappropriately categorised (aged >18 years),

erroneously reported as unrelated to child abuse, or

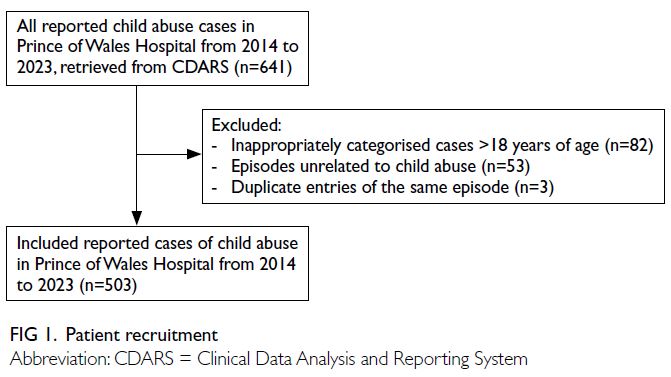

duplicate entries of the same episode (Fig 1).

Clinical data including patient demographics

(age at presentation and sex), clinical presentation,

type of abuse, imaging performed, multidisciplinary

case conferences (MDCCs) held, management

strategies, and any long-term adverse outcomes

were reviewed from electronic patient records and

case notes. Relevant imaging studies were reviewed

by the primary investigator (5 years of radiology

experience) and cross-checked against the original

reports. In cases of discrepancy, images were re-interpreted

through consensus reading with an

experienced paediatric radiologist (20 years of

radiology experience).

Results

Patient demographics and clinical

presentation

In total, 503 reported cases of child abuse were

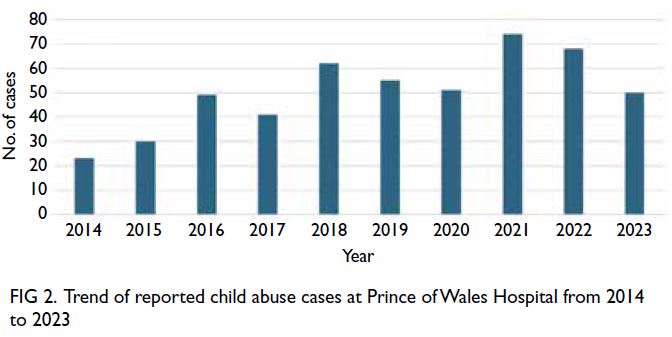

included in the study. The number of reported cases

showed an upward trend over the 10-year period,

from 23 cases in 2014 to 50 cases in 2023 (Fig 2).

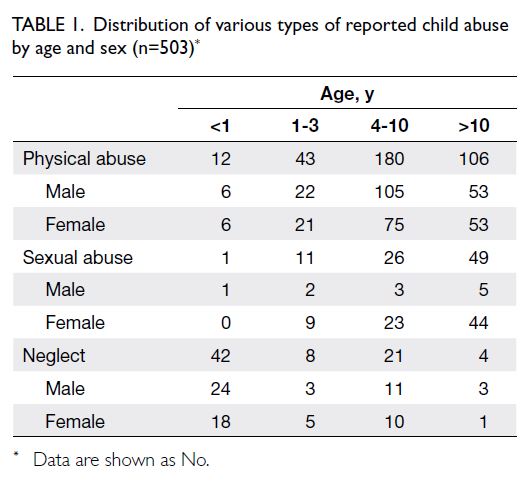

The case distribution is presented in Table 1.

The cohort comprised 265 (52.7%) girls and 238

(47.3%) boys. The mean age was 8.25 years (range,

0-17), with 55 cases (10.9%) involving infants

under 1 year of age. Physical abuse was the most

common type at presentation, accounting for 341

cases (67.8%). The vast majority (>99%) of patients

presented with erythematous marks, bruises, or

lacerations. Other presenting symptoms included

seizures, loss of consciousness, and vomiting. Sexual

abuse was the second most common type (n=87,

17.3%), followed by child neglect (n=75, 14.9%).

More than half of the cases (n=263, 52.3%)

were admitted via the Accident and Emergency

(A&E) Department. The vast majority of these

patients presented directly to our hospital, and only

two transferred from adjacent acute hospitals—one involving abusive head trauma requiring

neurosurgical intervention, and another with a

suspected vaginal tear necessitating input from

obstetricians and gynaecologists. Most of these patients (254 cases, 96.6%) were referred due to

clinical suspicion of abuse raised by non-offending

parents (n=137), social workers (n=78), the patients

themselves (n=22), or witnesses (n=17). In the

remaining nine cases (3.4%), suspicion was first

raised by medical staff either in the Emergency

Department/General Outpatient Clinic (n=4) or after

admission (n=5). Although medical staff identified a

relatively small proportion of these cases, many were

severe, including three abusive head trauma cases

initially presenting with seizures. In such cases,

abuse was only suspected after imaging.

The remaining 240 cases (47.7%) were admitted

through other channels, including referral by social

workers (n=203), neonatal admission (n=28),

abnormalities identified by medical staff during

follow-up or screening (n=8), and sibling screening

(n=1).

Imaging modalities and findings

Imaging was performed for 100 patients (19.9%),

including 86 cases with skeletal imaging, 24 with

neurological imaging, and one with abdominal

imaging. Among the 24 patients who underwent

neuroimaging, 10 also had skeletal imaging, while 14

received neuroimaging only.

Of the 86 patients who underwent skeletal

imaging, 77 had plain radiographs of the targeted

region as initial screening, and nine received a

complete skeletal survey. Most patients had minor

soft tissue injuries. Fractures were identified in

two patients: a supracondylar fracture in a 3-year-old

boy and a foot fracture in a 13-year-old girl,

representing 2.3% of all skeletal imaging cases

(Fig 3). Both fractures were detected on dedicated

radiographs directed at regions of pain, as indicated

by the patients. In another case, initial radiographs

in a 13-year-old boy showed no obvious fracture, but

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for persistent

wrist pain subsequently revealed a mild ligamentous

sprain.

Figure 3. (a) Anteroposterior plain radiograph of the right elbow showing a linear transverse supracondylar fracture of the right humerus (arrow). (b) Anteroposterior plain radiograph of the left fifth toe showing cortical buckling over the lateral aspect of the shaft of the left fifth metatarsal bone (arrow)

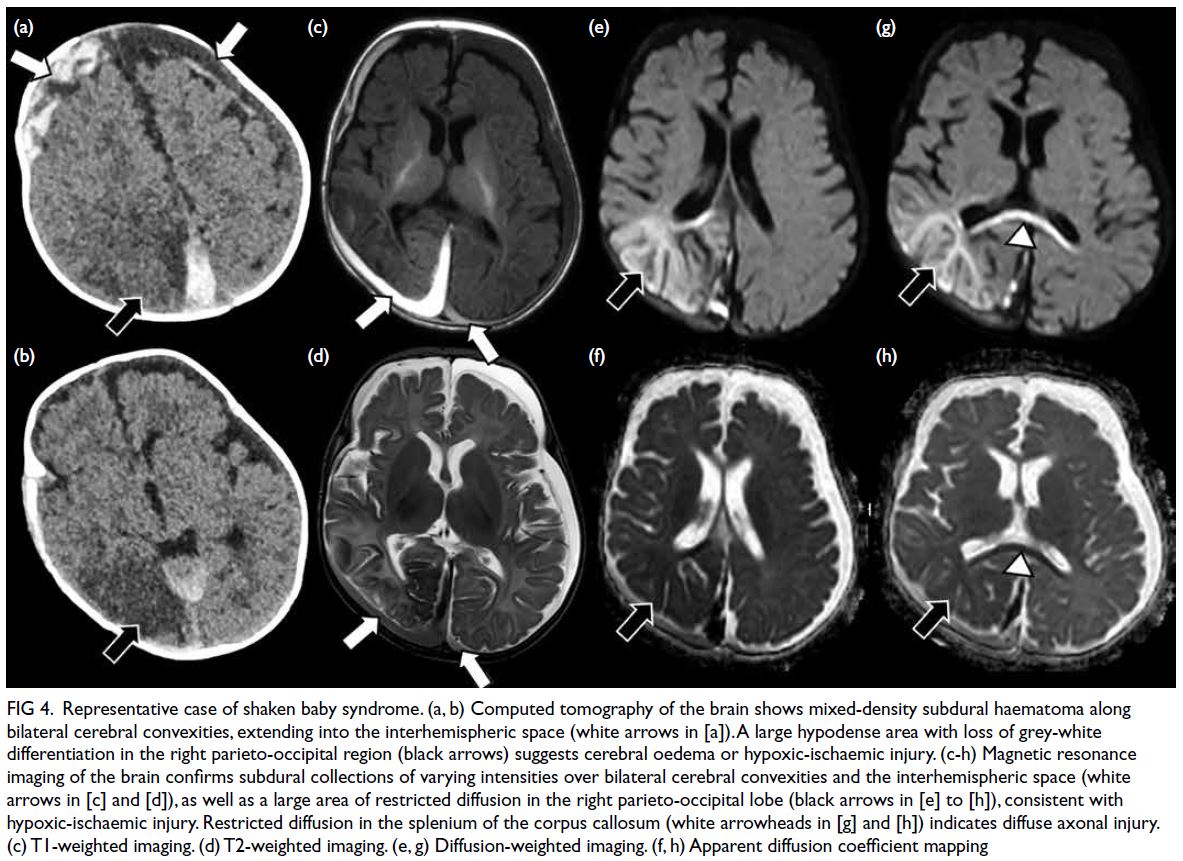

Computed tomography (CT) was the

initial imaging modality in 24 cases evaluated for

suspected intracranial injury; five cases (20.8%)

showed positive findings. Three cases (12.5%)

demonstrated alarming features suggestive of shaken

baby syndrome on initial brain CT scans, including

subdural haemorrhage (n=3) and cerebral oedema

(n=1), prompting further evaluation by MRI. Shaken

baby syndrome was confirmed in all three cases on

MRI, which showed subdural haemorrhage (n=3)

and brain parenchymal injuries, including diffuse

axonal injury (n=3) and hypoxic-ischaemic injury

(n=2) [Fig 4]. These patients, aged between 2 and

7 months, presented with non-specific symptoms

such as seizures (n=3), vomiting (n=2), and loss of

consciousness (n=1). Fundoscopic examination

confirmed multilayered retinal haemorrhages in all three cases, whereas skeletal surveys were

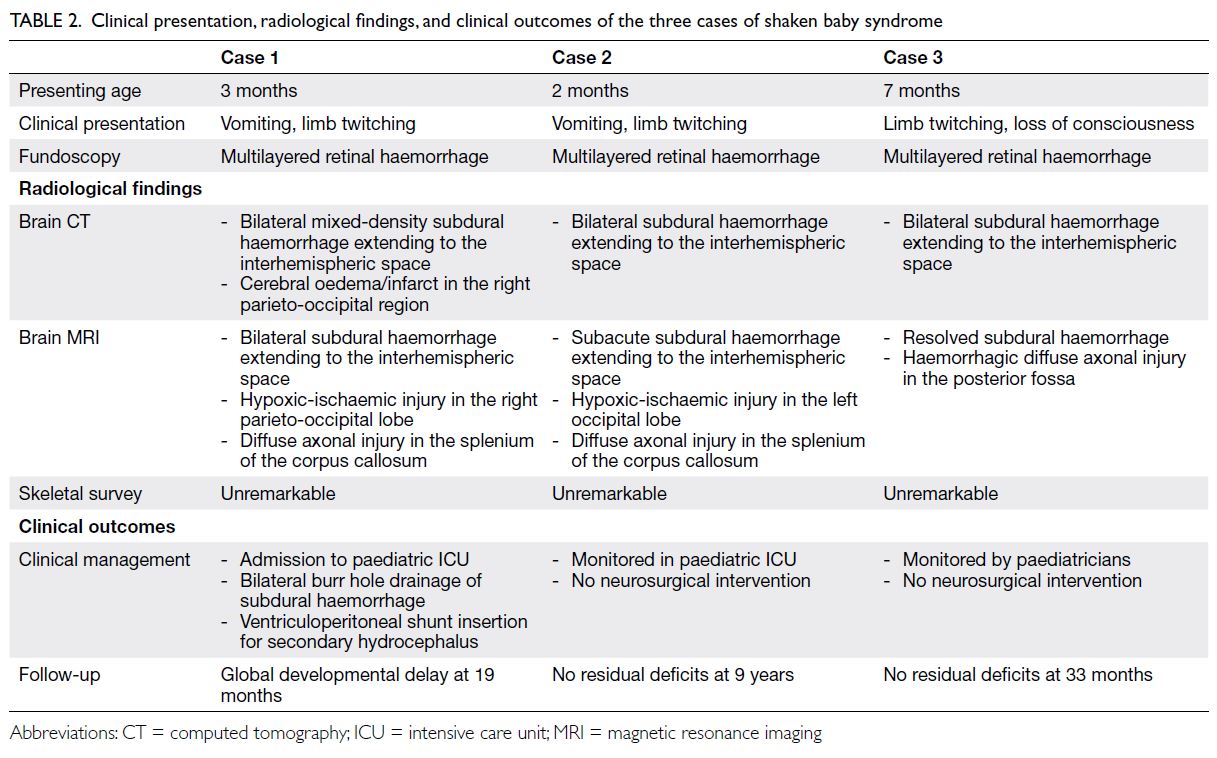

unremarkable (Table 2). The remaining two CT-positive

cases included one with a scalp haematoma

and another with a mildly depressed parietal skull

fracture; both lacked intracranial findings.

Figure 4. Representative case of shaken baby syndrome. (a, b) Computed tomography of the brain shows mixed-density subdural haematoma along bilateral cerebral convexities, extending into the interhemispheric space (white arrows in [a]). A large hypodense area with loss of grey-white differentiation in the right parieto-occipital region (black arrows) suggests cerebral oedema or hypoxic-ischaemic injury. (c-h) Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain confirms subdural collections of varying intensities over bilateral cerebral convexities and the interhemispheric space (white arrows in [c] and [d]), as well as a large area of restricted diffusion in the right parieto-occipital lobe (black arrows in [e] to [h]), consistent with hypoxic-ischaemic injury. Restricted diffusion in the splenium of the corpus callosum (white arrowheads in [g] and [h]) indicates diffuse axonal injury. (c) T1-weighted imaging. (d) T2-weighted imaging. (e, g) Diffusion-weighted imaging. (f, h) Apparent diffusion coefficient mapping

Table 2. Clinical presentation, radiological findings, and clinical outcomes of the three cases of shaken baby syndrome

Ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvis was

performed in one patient with persistent abdominal

pain; no clinically significant solid organ injury was

identified.

Multidisciplinary case conference assessment

and long-term adverse outcomes

Overall, 44 cases (8.7%) were dismissed for various

reasons, such as cross-border status, family

refusal, or discharge against medical advice. Of the

remaining 459 cases (91.3%) evaluated by MDCC,

documentation was not retrievable from clinical

records in 45 cases (8.9%).

Among the 414 cases with available MDCC

documentation or conclusions, child abuse was

confirmed in 199 cases (48.1%), comprising physical

abuse (n=95), child neglect (n=63), and sexual abuse

(n=41). Another 84 cases (20.3%) were categorised

as high-risk, involving suspected physical abuse

(n=81) or sexual abuse (n=3). Child abuse was not

established in the remaining 131 cases (31.6%); these

were considered to have low or moderate risk of

recurrence.

Of the 89 cases in which MDCC was dismissed

or notes were unavailable, more than half (n=63,

70.8%) had presented with suspected physical abuse,

followed by sexual abuse (n=22, 24.7%) and neglect

(n=4, 4.5%). All cases were deemed minor, with

no clinically or radiologically significant findings.

No specific treatment or long-term follow-up was

required.

The majority of cases exhibited minor severity

and were managed conservatively without long-term

adverse outcomes.

A long arm cast was applied for one patient

with a supracondylar fracture, whereas a resting

splint was prescribed for another patient with a

ligamentous wrist sprain. Both patients recovered

uneventfully after short-term follow-up (1 year) by

the orthopaedics team, with no residual impact on

daily functioning.

Two patients with severe abusive head

trauma required admission to the paediatric

intensive care unit. One of these patients warranted

multiple neurosurgical interventions, including

bilateral burr hole drainage and placement of a

ventriculoperitoneal shunt. The remaining two cases

of abusive head trauma were managed conservatively.

At the most recent follow-up, one patient—the most severely affected—demonstrated gross motor delay

at 19 months of age. All other patients showed no

neurological deficits or developmental delay to date.

No mortality was recorded in this cohort.

Repeated admissions for suspected child

abuse were identified in 22 cases. Of these, 16 were

recurrent, established cases of child abuse. In 14 of

these 16 cases, the type of abuse remained consistent

across episodes, whereas two cases involved different

types of abuse in separate incidents. Four cases

were initially classified as established child abuse,

but subsequent admissions were considered non-established,

with recurrence risk ranging from low to

high. Two cases were categorised as non-established

child abuse on both occasions but were considered

to have moderate or high risk of recurrence.

Discussion

This retrospective 10-year study documented a

significant rise in reported child maltreatment cases,

emphasising that child abuse remains an ongoing

medical and social concern. This issue persists

despite concerted efforts by the government and

various organisations to provide social support

to new mothers and at-risk families in an effort to

prevent child maltreatment.

Types of child abuse

Physical abuse was the most common type of

presentation in our study, consistent with data

from the Child Protection Registry10 and similar

findings from Singapore.11 The high prevalence of

physical abuse in Hong Kong may reflect cultural

differences in parenting practices, such that corporal

punishment remains more commonly accepted in

Chinese households than in Western contexts.12

Over 50% of families in Hong Kong use physical

punishment as part of child-rearing.13 In moments of

anger or impulsiveness, the line between ineffective

parenting and child abuse may easily be crossed.

Pattern of injury and imaging findings

The majority of cases in our study were considered mild in nature, with no serious long-term

consequences after clinical evaluation and

appropriate imaging. Fractures were infrequent,

comprising 0.4% of all reported child abuse cases

and 0.6% of all reported physical child abuse cases.

These rates are slightly lower than those reported in

previous Asian studies, which revealed fractures in

1% of all reported physical child abuse cases11 and

3.6% to 7% of all reported child abuse cases.14 15 The

present rates are substantially lower than the 28%

observed in a Western population.6 The fracture

detection rate among patients who underwent

imaging in our study (2.3%) was also considerably

lower than that in Western populations (24%-32%).7 8 Compared with a previous Hong Kong

study in 2005,15 our findings suggest a decline in

the overall fracture rate despite an overall increase

in reported child maltreatment cases, implying a

trend towards milder injuries in recent years. This

trend may reflect increased societal awareness of

the consequences of severe child abuse, potentially

leading parents to move away from traditional

forms of physical punishment (eg, caning) and

towards less injurious methods, such as striking

with the hand. Greater awareness may also facilitate

earlier detection and reporting, thereby preventing

escalation.

No fractures were identified on skeletal surveys

in the few cases of confirmed shaken baby syndrome

in our cohort. One case of parietal bone fracture

was documented—the parietal bone is among the

most commonly fractured skull bones, according

to current literature.14 16 The other identified

fractures—supracondylar and foot fractures—do

not reflect the classical abuse-specific fracture types

described in the literature, such as posteromedial

rib fractures or metaphyseal corner fractures.16

However, these findings align with previous studies

in Singapore, where the humerus was the most

frequently fractured bone.11 14 Our results also differ

from the findings of Fong et al,15 who reported that

forearm and rib fractures were most common in Hong Kong. With the exception of rib fractures, the

sites noted in our study are not typically associated

with non-accidental injury. This highlights potential

differences in injury severity and fracture patterns

between Asian and Western populations and

underscores the importance of maintaining clinical

suspicion for non-accidental injury, even in the

absence of classical fracture sites or textbook

imaging findings.16

Abusive head trauma is the leading cause of

morbidity and mortality among children subjected

to abuse, with an estimated morbidity rate of up to

80% and a mortality rate ranging from 15% to 30%.17 18

Despite the deceptively low overall occurrence

of abusive head trauma in our study (0.6% of all

reported physical child abuse cases and 0.9% of all

reported child abuse cases), compared with Western

counterparts (up to 40%-50%),6 9 it is notable that

20.8% of our imaged cases showed positive findings,

and shaken baby syndrome was confirmed in 12.5%

via MRI. All confirmed cases involved infants under

1 year of age, whose relatively oedematous brains,

immature intracranial vasculature, and poor neck

muscle control render them more susceptible to

the effects of abusive head trauma.19 It is therefore

imperative that neuroimaging be performed for all

children under 1 year of age with suspected non-accidental

injury, particularly those with abnormal

neurological signs, such as seizures or coma.4 Bilateral

subdural haemorrhages of varying densities, focal and

diffuse brain parenchymal injuries (eg, diffuse axonal

injury or cerebral oedema), and multilayered retinal

haemorrhages on fundoscopy, as demonstrated in

our study, are consistent with cardinal features of

abusive head trauma described in the literature.17 20

Our study also revealed more favourable morbidity

(33%) and mortality (0%) outcomes compared with

current literature reports,2 17 possibly due to the

relatively small number of cases.

Current practice in the management of cases

of suspected child abuse

At present, suspected child maltreatment presents

to our hospital via two main pathways: attendance

at the A&E Department for suspicious injuries,

and referral by social workers who observe unusual

behaviour or injuries.21 For cases requiring inpatient

care, the paediatric team conducts history taking and

physical examination, documents findings (including

clinical photographs), and manages the injuries.21

Relevant parties—such as social workers, clinical

psychologists, and police officers—are informed

as necessary.21 Minor cases may be assessed and

discharged directly from the A&E Department.21

An MDCC is typically convened within 10 days of

presentation, involving doctors, social workers,

school personnel, clinical psychologists, and police

officers to determine the nature of the incident, assess the risk of future maltreatment, and recommend

preventive measures.21

Radiologists play an active role in the

multidisciplinary management of child abuse—not

only in assessing the full extent of injuries but also

in detecting subtle, suspicious findings, alerting the

clinical team, and proactively contributing to early

intervention and the reduction of long-term adverse

outcomes. The reporting of suspicious injuries is

currently conducted on a voluntary basis, guided

by recommendations from the Social Welfare

Department.22 However, the recently gazetted

Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse Ordinance,23

which becomes effective in January 2026, will

impose a legal obligation on professionals to report

suspected injuries, thereby strengthening safeguards

for children.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest

retrospective study to investigate the clinical and

radiological features of child abuse in a regional

hospital in Hong Kong over the past decade. It

provides an updated local overview while drawing

comparisons with Western data to highlight

distinguishing features and emphasise the need for

greater attention to this critical issue.

This study had several limitations. First, it

was a retrospective analysis based on voluntarily

reported cases, and some instances of child abuse

may have been under-recognised or underreported

by attending clinicians. A small number of cases

also lacked accessible MDCC notes or conclusions

due to record loss over time. Second, our dataset

includes only admitted cases from a single regional

hospital, which may have introduced selection bias

because minor cases discharged directly from A&E

were excluded. The generalisability of our findings

is limited, given that the distribution of child

maltreatment cases varies substantially across Hong

Kong districts. Sha Tin accounted for approximately

6.2% of all reported child maltreatment cases from

2014 to 2023, whereas Yuen Long accounted of 12%.24

Variations in demographic and socio-economic

backgrounds across districts may also influence

clinical presentation and severity of injuries; further

investigation is warranted. Third, despite the large

cohort of child abuse cases included in our series,

the proportion of positive imaging findings remains

relatively small. Larger-scale studies are needed

to better characterise local injury patterns. Finally,

due to the extended retrospective recruitment

period, follow-up durations varied widely—from 15 months in recent cases to 9 years in earlier cases.

Consequently, the long-term effects of abusive head

trauma may not yet be evident in patients with

shorter follow-up, highlighting the need for further

longitudinal assessment into later childhood.

Conclusion

This study provides an updated overview of the

clinical and radiological features of child abuse

in Hong Kong, revealing patterns that differ

from those described in Western literature.

Although most cases involved only minor clinical

manifestations, a small proportion of patients

exhibited positive imaging findings of skeletal or

neurological injury, which may carry serious long-term

consequences. Radiologists play a critical role

in the multidisciplinary management of child abuse,

both in flagging suspicious injuries to alert clinicians

and in evaluating the full extent of trauma to protect

children from further harm.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CYM Young, WCW Chu.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CYM Young, WCW Chu.

Drafting of the manuscript: CYM Young.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CYM Young, WCW Chu.

Drafting of the manuscript: CYM Young.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was conducted in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from

the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories

East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong

(Ref No.: 2024.071). The requirement for informed patient

consent was waived by the Committee due to the retrospective

design of the research.

References

1. Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E,

Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment

in high-income countries. Lancet 2009;373:68-81. Crossref

2. Guastaferro K, Shipe SL. Child maltreatment types by

age: implications for prevention. Int J Environ Res Public

Health 2023;21:20. Crossref

3. Caffey J. Multiple fractures in the long bones of infants

suffering from chronic subdural hematoma. Am J

Roentgenol Radium Ther 1946;56:163-73.

4. The Society and College of Radiographers; The Royal

College of Radiologists. The Radiological Investigation

of Suspected Physical Abuse in Children (Revised First

Edition). London: The Royal College of Radiologists; 2018.

Available from: https://www.rcr.ac.uk/media/nznl1mv4/rcr-publications_the-radiological-investigation-of-suspected-physical-abuse-in-children-revised-first-edition_november-2018.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

5. Wootton-Gorges SL, Soares BP, Alazraki AL, et al. ACR

Appropriateness Criteria® suspected physical abuse—child. J Am Coll Radiol 2017;14:S338-49. Crossref

6. Ward A, Iocono JA, Brown S, Ashley P, Draus JM Jr. Non-accidental

trauma injury patterns and outcomes: a single

institutional experience. Am Surg 2015;81:835-8. Crossref

7. Day F, Clegg S, McPhillips M, Mok J. A retrospective case

series of skeletal surveys in children with suspected non-accidental

injury. J Clin Forensic Med 2006;13:55-9. Crossref

8. Loos MH, Ahmed T, Bakx R, van Rijn RR. Prevalence

and distribution of occult fractures on skeletal surveys in

children with suspected non-accidental trauma imaged

or reviewed in a tertiary Dutch hospital. Pediatr Surg Int

2020;36:1009-17. Crossref

9. Rosenfeld EH, Johnson B, Wesson DE, Shah SR, Vogel AM,

Naik-Mathuria B. Understanding non-accidental trauma

in the United States: a national trauma databank study. J

Pediatr Surg 2020;55:693-7. Crossref

10. Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Child Protection Registry Statistical Report 2023. 2024.

Available from: https://www.swd.gov.hk/storage/asset/section/654/Annual%20CPR%20Report%202023_Biligual_Final.pdf . Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

11. Chew YR, Cheng MH, Goh MC, Shen L, Wong PC,

Ganapathy S. Five-year review of patients presenting with

non-accidental injury to a children’s emergency unit in

Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap 2018;47:413-9. Crossref

12. Liu W, Guo S, Qiu G, Zhang SX. Corporal punishment

and adolescent aggression: an examination of multiple

intervening mechanisms and the moderating effects of

parental responsiveness and demandingness. Child Abuse

Negl 2021;115:105027. Crossref

13. Tang CS. Corporal punishment and physical maltreatment

against children: a community study on Chinese parents in

Hong Kong. Child Abuse Negl 2006;30:893-907. Crossref

14. Gera SK, Raveendran R, Mahadev A. Pattern of fractures

in non-accidental injuries in the pediatric population in

Singapore. Clin Orthop Surg 2014;6:432-8. Crossref

15. Fong CM, Cheung HM, Lau PY. Fractures associated with

non-accidental injury—an orthopaedic perspective in a local regional hospital. Hong Kong Med J 2005;11:445-51.

16. Offiah A, van Rijn RR, Perez-Rossello JM, Kleinman PK.

Skeletal imaging of child abuse (non-accidental injury).

Pediatr Radiol 2009;39:461-70. Crossref

17. Sidpra J, Chhabda S, Oates AJ, Bhatia A, Blaser SI, Mankad K.

Abusive head trauma: neuroimaging mimics and diagnostic

complexities. Pediatr Radiol 2021;51:947-65. Crossref

18. Karibe H, Kameyama M, Hayashi T, Narisawa A, Tominaga T.

Acute subdural hematoma in infants with abusive head

trauma: a literature review. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo)

2016;56:264-73. Crossref

19. Hung KL. Pediatric abusive head trauma. Biomed J

2020;43:240-50. Crossref

20. Sun DT, Zhu XL, Poon WS. Non-accidental subdural

haemorrhage in Hong Kong: incidence, clinical features,

management and outcome. Childs Nerv Syst 2006;22:593-8. Crossref

21. So EC, Chan D. Management of Child Maltreatment

(Abuse). Hong Kong: Hospital Authority New Territories

East Cluster Prince of Wales Hospital Department of

Paediatrics; 2024.

22. Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Protecting Children from Maltreatment Procedural

Guide for Multi-disciplinary Co-operation (Revised

2020). Jan 2020. Available from: https://www.swd.gov.hk/storage/asset/section/652/en/Procedural_Guide_Core_Procedures_(Revised_2020)_Eng_2Nov2021.pdf . Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

23. Legislative Council, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse Ordinance. 2024.

Available from: https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr2024/english/ord/2024ord023-e.pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2024.

24. Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Statistics on child protection, spouse/cohabitant battering

and sexual violence cases captured by the Child Protection

Registry (CPR) and the Central Information System on

Spouse/Cohabitant Battering Cases and Sexual Violence

Cases (CISSCBSV). Social Welfare Department; 2025.

Available from: https://data.gov.hk/en-data/dataset/hk-swd-fcw-ca-scb-sv-stat/resource/6229e2b4-73d0-4285-a892-838c683c9966. Accessed 8 Aug 2025.