Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:Epub 7 Aug 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PERSPECTIVE

A call for interdisciplinary bereavement care in

miscarriage and stillbirth: a stepped-care model approach

Celia HY Chan, PhD, MSW1,2,3; Sherman S Zhang, MSW2; Chris NL Ng, MSS2; Ernest HY Ng, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)3; Raymond HW Li, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)3; LM Yeung, MPH, BNur4; Kathy SF Wong, MPhil5

1 Department of Social Work, Melbourne School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

2 Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Family Wellness Centre, Hong Kong Young Women’s Christian Association, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Celia HY Chan (celia.chan@unimelb.edu.au)

Background

Bereavement following pregnancy loss, such as miscarriage or stillbirth, profoundly affects individuals

and families due to its sudden and traumatic nature.

The emotional toll can manifest as grief, depression,

anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),

often exacerbated by uncertainty and a lack of

preparedness. While healthcare primarily addresses

the medical and surgical aspects of management,

psychosocial support remains insufficient, leaving

many individuals and families feeling isolated.

Integrated perinatal bereavement care is needed

across hospital and community settings. This article

advocates for an interdisciplinary, stepped-care

model to provide tailored emotional, psychological,

and practical support. Embedding this framework

within healthcare systems can effectively address

the physical and psychosocial needs of bereaved

individuals and families, promoting healing and

overall well-being.

Definition and prevalence of miscarriage and

stillbirth

Miscarriage, defined as the spontaneous loss of

pregnancy before a specific gestational threshold,

affects 15% to 20% of pregnancies globally,1 with an

estimated 23 million cases annually, equating to 44

cases per minute.2 While the American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the European

Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

classify early pregnancy loss as occurring within the

first 12 6/7 weeks of gestation,3 4 the World Health

Organization includes fetal weight criteria.5 In Hong

Kong, the Hospital Authority and the Hong Kong

SAR Government define miscarriage as pregnancy

loss before 24 weeks of gestation.6 According to

the Department of Health,7 nearly 10 000 cases of spontaneous abortion, medical abortion, and other

abortive outcomes were reported in 2023.

Stillbirth, defined as fetal death beyond a

certain gestational age, affects approximately 1.9

million pregnancies each year, occurring at a global

rate of 2.3 per 1000 births.8 The World Health

Organization defines stillbirth as fetal death at 28

weeks or later (or a weight of ≥1000 g if gestational

age is unknown), whereas the United States sets the

threshold at 20 weeks.9 In Hong Kong, stillbirth is

defined as fetal death at 24 weeks or later. A 20-year

retrospective study analysing 128 967 deliveries

between 2000 and 2019 recorded 429 stillbirths,

with the perinatal mortality rate declining by 16.7%,

from 5.52 per 1000 in 2000-2009 to 4.59 per 1000 in

2010-2019. The singleton stillbirth rate also slightly

decreased from 3.27 to 2.91 per 1000 births.10 These

reductions are attributed to advancements in early

prenatal screening and diagnosis of congenital and

genetic conditions.

Psychological impact and psychiatric

morbidity after pregnancy loss

Women who experience pregnancy loss are highly

susceptible to the onset of psychiatric morbidities,

including depression, anxiety, and PTSD.11 12 13 14

Depression is particularly prevalent, with a systematic

review reporting prevalence rates ranging from 5.4%

(minor depression as defined by the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM], fourth

edition) to 18.6% (depressive disorders as defined by

the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth

Revision).13 For most women, depressive symptoms

peak in the initial months following pregnancy loss

and tend to decline over time. However, some women

may also experience significant anxiety symptoms,

including generalised anxiety and panic attacks, or develop PTSD, particularly when the pregnancy loss

is experienced as sudden, traumatic, or medically

complex. When compounded by profound grief,

these psychiatric responses can result in long-term

mental health challenges, including chronic

depression, suicidal ideation, and prolonged grief

disorder. Some women continue to experience these

symptoms even years after their loss.15

Grief following pregnancy loss is distinct and

often marginalised, lacking public acknowledgement

or support. This is particularly evident in cultures

such as Chinese society, where early-stage

pregnancies are commonly concealed.16 Such cultural

taboos can lead to isolated mourning, hindering

emotional expression and processing of grief. This

disenfranchisement intensifies the psychological

burden, highlighting the need for specialised mental

health interventions tailored to women coping

with pregnancy loss.17 Some individuals may even

develop prolonged grief reactions or persistent

complex bereavement disorder.15 These conditions

are characterised by intense and prolonged grief

symptoms, impairments in daily functioning, and

difficulties adapting to the loss, further complicating

the emotional distress experienced by bereaved

parents.

Clinical practice guidelines on management

of pregnancy loss in various countries

Recent advances in bereavement care for pregnancy

loss emphasise the integration of counselling

and psychotherapy to address emotional needs.

Guidelines from leading organisations such as the

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

(United Kingdom)18 and The Royal Australian

and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (Australia)19 advocate for counselling,

stigma reduction, respectful maternity care, and

planning for future pregnancy. The RESPECT Study

(Randomised Evaluation of Sexual health Promotion

Effectiveness informing Care and Treatment)

reinforces the global consensus on bereavement

care.20 Prioritising counselling and psychotherapy

as integral components of bereavement care enables

healthcare providers to offer tailored support to

bereaved individuals.

Perinatal bereavement care: the Hong Kong

context

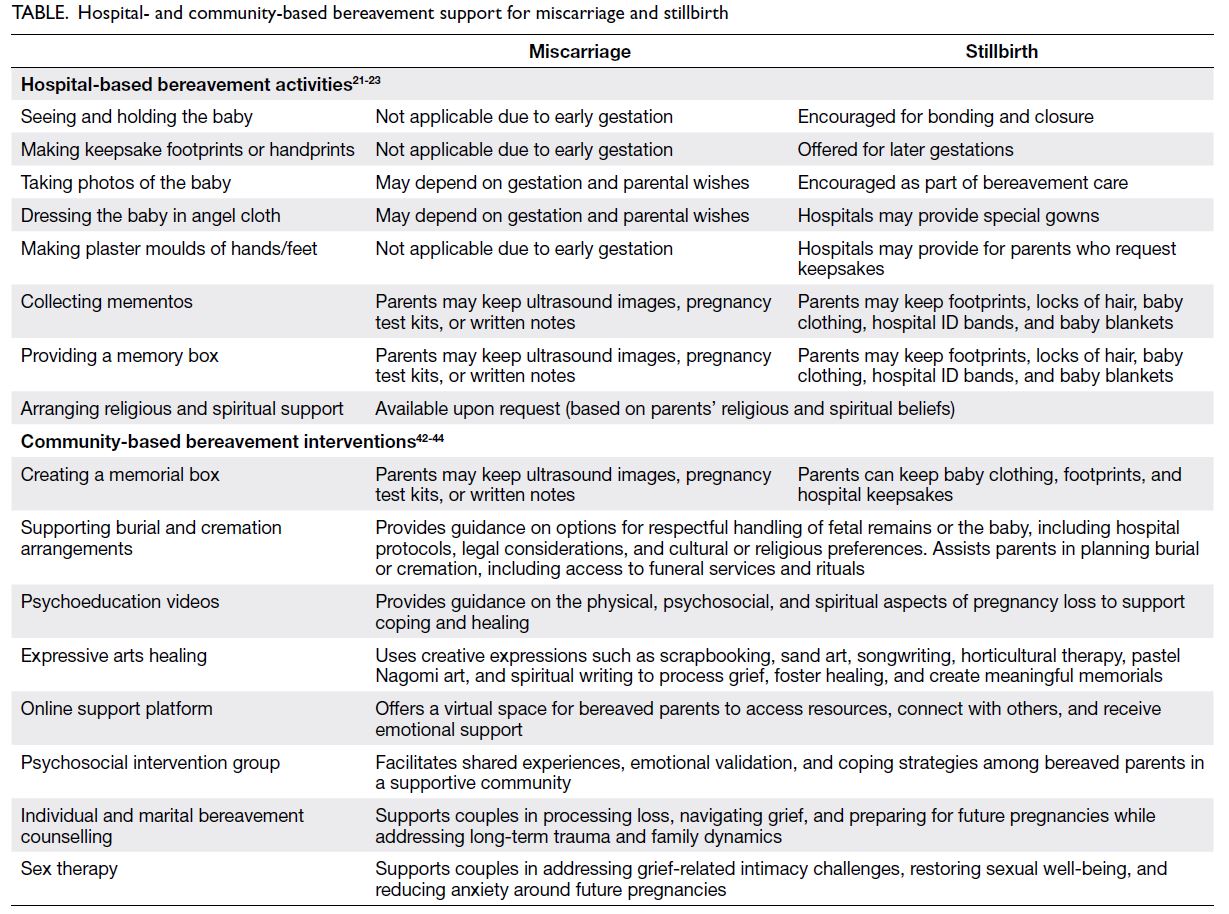

Perinatal bereavement care offers emotional,

psychological, and practical support to help families

cope with grief following miscarriage, stillbirth,

or neonatal death. Timely support is crucial

for parents coping with pregnancy loss. While

medical care primarily addresses complications

and interventions such as medication or surgery,

healthcare professionals can also play a role in

facilitating meaningful memorial experiences, such as seeing and holding the baby, creating keepsakes,

or capturing memories through photography. These

practices help parents process grief and create lasting

remembrances. Additional perinatal mourning

resources are detailed in the Table.21 22 23

The Hong Kong SAR Government has made

substantial progress in improving fetal burial and

cremation services. Previously, fetuses miscarried

before 24 weeks of gestation were classified as

medical waste, limiting options for grieving parents.

In 2017, the Government amended relevant

regulations to permit cremation for these fetuses,

and six private cemeteries now offer services for

storing the remains.24 The Hospital Authority

has also updated its guidelines to promote the

compassionate handling of fetal remains; however,

legal and logistical challenges remain.

However, ongoing bereavement support often

diminishes following hospital discharge, leaving

parents feeling isolated and uncertain about how to

seek emotional support or counselling. Integrating

comprehensive bereavement care is essential to

ensure continuous access to emotional support,

counselling, and resources for navigating long-term

grief.

A call for a stepped-care model in perinatal

bereavement care

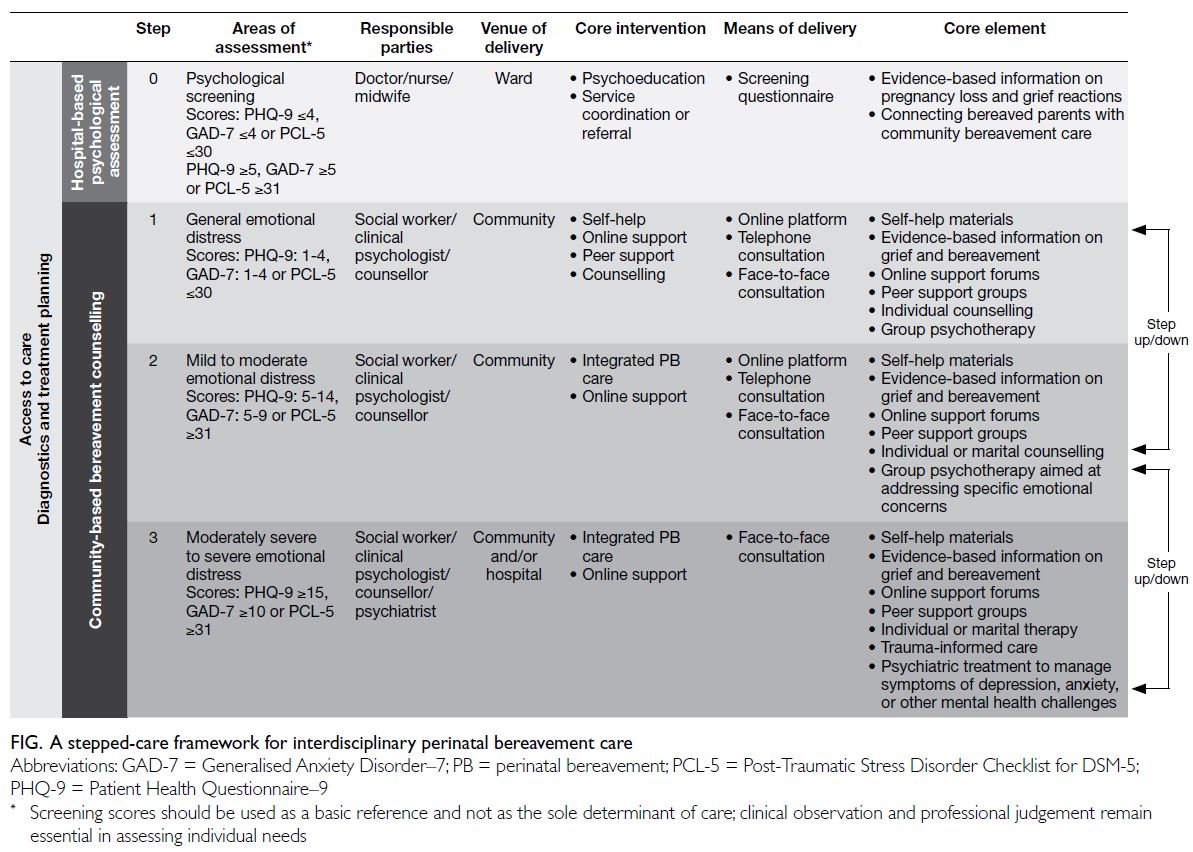

In recent years, stepped-care models have been

widely adopted across global and local public health

and mental health systems due to their tiered

approach to care delivery, which has demonstrated

positive outcomes and helped alleviate healthcare

burdens.25 26 27 28 Newman proposed a cost-effective

method for identifying at-risk individuals and

delivering stepped interventions based on

standardised psychometric assessments.29 This

model begins with less intrusive, lower-cost options

and escalates care as needed for individuals with

greater mental health needs. Stepped care also

accommodates a spectrum of interventions, from

low-intensity self-help to specialised high-intensity

therapies, ensuring timely and appropriate care.30

Perinatal bereavement care supports parents

through the complexities of loss by providing clear,

empathetic information about its causes, physical

recovery, and emotional responses. Sensitive

communication is crucial for addressing parents’

emotional needs during this distressing time. A

systematic review and meta-analysis found that

stepped-care interventions were significantly more

effective than usual care in reducing depression.31

Incorporating a stepped-care model into

bereavement support offers a structured framework,

with varying levels of intervention tailored to the

degree of psychosocial distress among bereaved

parents. Comprehensive screening facilitates

assessment of distress severity, guiding parents towards the most appropriate level of support. This

model fosters emotional healing and resilience,

ensuring that bereaved parents receive the right care

at the right time.

Step 0: Hospital-based psychological

screening and follow-up

The provision of follow-up care through detailed

information about the causes of loss, associated

symptoms, recovery, and future pregnancy

prospects empowers individuals to prioritise their

health, make informed decisions, and navigate their

grief. Discussions with bereaved parents should

address the risks and benefits of future pregnancies,

considering their physical and emotional readiness

along with medical causes. This dialogue should

also include available support services, such as

preconception counselling and specialised high-risk

pregnancy care.

Standardised psychological screening

enables consistent assessment, effective triage, and

appropriate referrals. A scoping review identified 93 studies involving 6248 women who had terminated

pregnancies due to fetal anomalies, with the most

commonly used psychological tools being the

Perinatal Grief Scale (22%) and the Impact of Event

Scale–Revised (18%).32 Additional measures, such

as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,33

the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9),21

the Generalised Anxiety Disorder–7 (GAD-7),22

and the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

for DSM-5 (PCL-5),23 have been utilised to assess

emotional distress, anxiety, depression, and trauma-related

symptoms. In Hong Kong, the 12-item

General Health Questionnaire combined with the

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I

Disorders identified psychiatric morbidity following

miscarriage.14 34

Although grief is a natural emotional response

to pregnancy loss, depression, generalised anxiety,

and post-traumatic stress are clinically actionable

screening parameters due to their prevalence,

impact, and established treatment pathways.35

Unlike grief which can vary in duration and intensity, conditions such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD

may become pathological, substantially impairing

daily functioning, increasing the risk of suicidal

ideation, and influencing future reproductive

decision making.

Given time constraints, clinician workload and

resource limitations, comprehensive psychological

assessments may be impractical. A brief yet reliable

screening tool is therefore more feasible for early

identification and intervention. The PHQ-9, GAD-7,

and PCL-5 have been validated and utilised across

diverse and general populations and offer a practical

approach to mental health screening.36 37 38 39 40 41 The

abovementioned Step 0 is conducted using these

tools to assess depressive symptoms, generalised

anxiety, and post-traumatic stress. Individuals with

minimal distress (scores: PHQ-9 ≤4, GAD-7 ≤4, and

PCL-5 ≤30) may not require immediate intervention,

whereas those with elevated distress (scores: PHQ-9

≥5, GAD-7 ≥5, or PCL-5 ≥31) should receive further

psychological support and appropriate referrals.

This structured screening process facilitates early

identification of individuals in need of additional psychosocial support. The Figure illustrates the

stepped-care framework, integrating psychological

assessment into medical treatment to ensure that

bereaved parents receive services tailored to their

needs.

Steps 1 to 3: Community-based psychosocial

support

Grief and emotional distress following pregnancy loss

can vary, necessitating tailored support. Accessible,

community-based care ensures that bereaved

parents receive appropriate psychosocial assistance.

Beyond medical and psychological interventions,

connecting bereaved parents with non-governmental

organisations and community resources is essential.

These organisations provide guidance on burial

or cremation arrangements, funeral services, and

bereavement support, helping families to navigate

their grief beyond the hospital setting (Table42 43 44). A

stepped-care model based on PHQ-9, GAD-7, and

PCL-5 scores enables structured intervention at

varying levels of emotional distress, ensuring that

individuals receive care aligned with their needs.

Step 1: General emotional distress

For individuals experiencing general emotional

distress (scores: PHQ-9: 1-4, GAD-7: 1-4, or PCL-5

≤30), low-intensity support is recommended.

Although clinical intervention may not be necessary,

emotional validation, short-term counselling, online

forums, self-help materials, and peer support can

offer reassurance. Psychoeducational workshops on

grief and coping may also be helpful. A brief follow-up

via telephone or through primary care helps

ensure timely support if distress increases.

Step 2: Mild to moderate emotional distress

For individuals experiencing mild to moderate

emotional distress (scores: PHQ-9: 5-14, GAD-7:

5-9, or PCL-5 ≥31), structured psychosocial care

is beneficial. Support may include individual or

group therapy, bereavement counselling, expressive

activities, and self-help tools such as journaling,

art therapy, and mindfulness. Online mental health

resources with guided self-help tools can also be

valuable. Periodic reassessment ensures ongoing

care and timely referrals if distress escalates, enabling

appropriate intervention based on evolving needs.

Step 3: Moderately severe to severe emotional

distress

For individuals experiencing moderate to severe

emotional distress (scores: PHQ-9: ≥15, GAD-7:

≥10, or PCL-5 ≥31), a multidisciplinary approach

is required. Psychological symptoms at this severity

may impair daily functioning, strain relationships, or

affect decision making regarding future pregnancies.

Support may include individual therapy, trauma-informed

care, family counselling, and psychiatric

evaluation. Immediate intervention is crucial for

those at risk of prolonged grief disorder, severe

depression, or suicidal ideation. Close monitoring

and coordinated care among hospital-based

professionals, community grief services, and

primary care providers help ensure continuity and

timely support.

Capacity building for healthcare

professionals

Enhancing healthcare professionals’ capacity for

perinatal bereavement care requires structured

strategies. Key approaches include developing

patient-centred bereavement care plans, training

staff in grief support, and establishing dedicated

teams. The integration of psychosocial assessments,

mental health referrals, and staff support fosters

compassionate care. Sensitivity, empathy, and

ongoing training improve service quality. Strategies

to provide follow-up care, referrals, and clear

information empower families in decision making.

By recognising the long-term impact of grief, sustained support can ensure continuity of care,

thereby strengthening bereavement services within

Hong Kong’s healthcare system.

Conclusion

Ensuring continuity of care is essential in supporting

families affected by pregnancy loss. Integrated

bereavement care, delivered with empathy,

acknowledges the profound impact on bereaved

parents. A holistic approach addressing diverse

emotional and practical needs is vital, supported by

a structured care model grounded in evidence-based

practices. Collaborations among medical doctors,

psychiatrists, midwives, clinical psychologists, social

workers, and counsellors are key, encompassing

counselling and access to resources such as support

groups. Prioritising continuity and interdisciplinary

teamwork fosters healing and recovery from the

profound grief of pregnancy loss.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CHY Chan.

Acquisition of data: CHY Chan, SS Zhang, CNL Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: CHY Chan, SS Zhang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CHY Chan, CNL Ng, EHY Ng, RHW Li, LM Yeung, KSF Wong.

Acquisition of data: CHY Chan, SS Zhang, CNL Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: CHY Chan, SS Zhang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CHY Chan, CNL Ng, EHY Ng, RHW Li, LM Yeung, KSF Wong.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

The stepped-care model used in this study was developed

under the Jockey Club Perinatal Bereavement Care Project,

a community-based initiative supported by the Hong Kong

Jockey Club Charities Trust (Ref No.: 2021-0395). The funder

had no role in the study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

References

1. Tong F, Wang Y, Gao Q, et al. The epidemiology of

pregnancy loss: global burden, variable risk factors, and

predictions. Hum Reprod 2024;39:834-48. Crossref

2. Quenby S, Gallos ID, Dhillon-Smith RK, et al. Miscarriage

matters: the epidemiological, physical, psychological,

and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. Lancet

2021;397:1658-67. Crossref

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’

Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG

Practice Bulletin No. 200: early pregnancy loss. Obstet

Gynecol 2018;132:e197-207. Crossref

4. Kolte AM, Bernardi LA, Christiansen OB, et al. Terminology

for pregnancy loss prior to viability: a consensus statement

from the ESHRE early pregnancy special interest group.

Hum Reprod 2015;30:495-8. Crossref

5. World Health Organization. Definitions and Indicators in Family Planning Maternal & Child Health and

Reproductive Health used in the WHO Regional Office for

Europe. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe;

2000.

6. Hong Kong SAR Government. Employment Ordinance (Cap 57). Available from: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap57!en?INDEX_CS=N. Accessed 12 Jul 2025.

7. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Tables on health status and health services 2023. Available

from: https://www.dh.gov.hk/english/pub_rec/pub_rec_ar/pdf/2324/supplementary_table2023.pdf . Accessed 12 Jul 2024.

8. World Health Organization. Stillbirth rate (per 1000 total

births): latest data. Available from: https://platform.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/indicator-explorer-new/MCA/stillbirth-rate-(per-1000-total-births). Accessed 12 Jul 2025.

9. Smith LK, Morisaki N, Morken NH, et al. An international

comparison of death classification at 22 to 25 weeks’

gestational age. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20173324. Crossref

10. Wong ST, Tse WT, Lau SL, Sahota DS, Leung TY. Stillbirth

rate in singleton pregnancies: a 20-year retrospective study

from a public obstetric unit in Hong Kong. Hong Kong

Med J 2022;28:285-93. Crossref

11. Farren J, Jalmbrant M, Ameye L, et al. Post-traumatic

stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage or

ectopic pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open

2016;6:e011864. Crossref

12. Xiao M, Huang S, Hu Y, Zhang L, Tang G, Lei J. Prevalence

of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder and its

determinants in Mainland China: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2023;44:76-85. Crossref

13. Mergl R, Quaatz SM, Lemke V, Allgaier AK. Prevalence

of depression and depressive symptoms in women with

previous miscarriages or stillbirths—a systematic review.

J Psychiatr Res 2024;169:84-96. Crossref

14. Sham AK, Yiu MG, Ho WY. Psychiatric morbidity

following miscarriage in Hong Kong. Gen Hosp Psychiatry

2010;32:284-93. Crossref

15. Bodunde EO, Buckley D, O’Neill E, et al. Pregnancy and

birth complications and long-term maternal mental health

outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG

2025;132:131-42. Crossref

16. Sun JC, Rei W, Chang MY, Sheu SJ. Care and management

of stillborn babies from the parents’ perspective: a

phenomenological study. J Clin Nurs 2022;31:860-8. Crossref

17. Shaohua L, Shorey S. Psychosocial interventions on

psychological outcomes of parents with perinatal loss:

a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud

2021;117:103871. Crossref

18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial

management. 2019. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng126. Accessed 12 Jul 2025.

19. Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines. Australian Living

Evidence Collaboration; 2025.

20. Shakespeare C, Merriel A, Bakhbakhi D, et al. The

RESPECT Study for consensus on global bereavement care

after stillbirth. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2020;149:137-47. Crossref

21. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Patient Health

Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) [database record]. American

Psychological Association PsycTests; 1999. Crossref

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092-7. Crossref

23. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Palmieri PA, Keane TM, Marx BP,

Schnurr PP. PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). United

States: National Center for PTSD; 2013.

24. Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government.

LCQ16: Handling of abortuses [press release]. 28 June

2017. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201706/28/P2017062800450.htm. Accessed 12 Jul 2025.

25. Wang Y, Hu M, Zhu D, Ding R, He P. Effectiveness of

collaborative care for depression and HbA1c in patients

with depression and diabetes: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Int J Integr Care 2022;22:12. Crossref

26. Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A.

Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making

sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and

meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:484-93. Crossref

27. Lee WK, Lo A, Chong G, et al. New service model for

common mental disorders in Hong Kong: a retrospective

outcome study. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2019;29:75-80. Crossref

28. Tang A, Liang HJ, Ungvari GS, Tang WK. Screening for

psychiatric morbidity in the postpartum period: clinical

presentation and outcome at one-year follow-up. J

Womens Health Care 2014;3:147. Crossref

29. Newman MG. Recommendations for a cost-offset model

of psychotherapy allocation using generalized anxiety

disorder as an example. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:549-55. Crossref

30. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Depression in adults: treatment and management.

Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222. Accessed 12 Jul 2025.

31. van Straten A, Hill J, Richards DA, Cuijpers P. Stepped care

treatment delivery for depression: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2015;45:231-46. Crossref

32. Slade L, Obst K, Deussen A, Dodd J. The tools used to assess

psychological symptoms in women and their partners after

termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly: a scoping

review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2023:288:44-8. Crossref

33. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and

Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361-70. Crossref

34. Lok IH, Lee DT, Yip SK, Shek D, Tam WH, Chung TK.

Screening for post-miscarriage psychiatric morbidity. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:546-50. Crossref

35. Farren J, Jalmbrant M, Ameye L, et al. Post-traumatic

stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage or

ectopic pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open

2016;6:e011864. Crossref

36. Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening

Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient

Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect

major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis.

BMJ 2019;365:l1476. Crossref

37. Kroenke K. PHQ-9: global uptake of a depression scale.

World Psychiatry 2021;20:135-6. Crossref

38. Saunders R, Moinian D, Stott J, et al. Measurement

invariance of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 across males and

females seeking treatment for common mental health

disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2023;23:298. Crossref

39. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The Patient

Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry

2010;32:345-59. Crossref

40. Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL.

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5

(PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation.

J Trauma Stress 2015;28:489-98. Crossref

41. Horesh D, Nukrian M, Bialik Y. To lose an unborn child:

post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive

disorder following pregnancy loss among Israeli women.

Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018;53:95-100. Crossref

42. Caritas Family Service. Jockey Club Perinatal Bereavement

Care Project Grace Port–Caritas Miscarriage Support Centre. 2025. Available from: https://family.caritas.org.hk/. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

43. Department of Social Work and Social Administration,

The University of Hong Kong. Jockey Club Perinatal

Bereavement Care Project Department of Social Work and

Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong. 2025.

Available from: https://www.jcperinatal-bc.hk/. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.

44. Hong Kong Young Women’s Christian Association. Jockey

Club Perinatal Bereavement Care Project Hong Kong

Young Women’s Christian Association. 2025. Available

from: https://fwcyyc.ywca.org.hk. Accessed 17 Feb 2025.