© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Through the lens of history: century-old snapshots from Tsan Yuk Hospital

Stephanie Adams, MD, MWomHMed1; CP Lee, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2 Elce Au Yeung, RNM, MN3; WC Leung, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of

Medical Sciences

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Tsan Yuk Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 School of Midwifery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Founded in 1922, Tsan Yuk Hospital celebrates its

103rd anniversary this year. As one of Hong Kong’s

first maternity hospitals, Tsan Yuk Hospital provided

safe, professional in-patient obstetric services to

women and their newborns until 3 November 2001,

when the last delivery occurred.1 Since then, Tsan

Yuk Hospital has transitioned from a standalone

maternity hospital to an out-patient centre focused

on antenatal care.1

In 1928, Prof Richard Edwin Tottenham, one

of the first obstetrics and gynaecology professors

to work at the hospital, published a clinical report

containing photographs of the then newly built

institution’s labour ward and the operating theatre

(Figs 1 and 2).2 Comparing these with their modern-day

equivalents (Figs 3 and 4) highlights the

advancement of obstetric care over the last century.

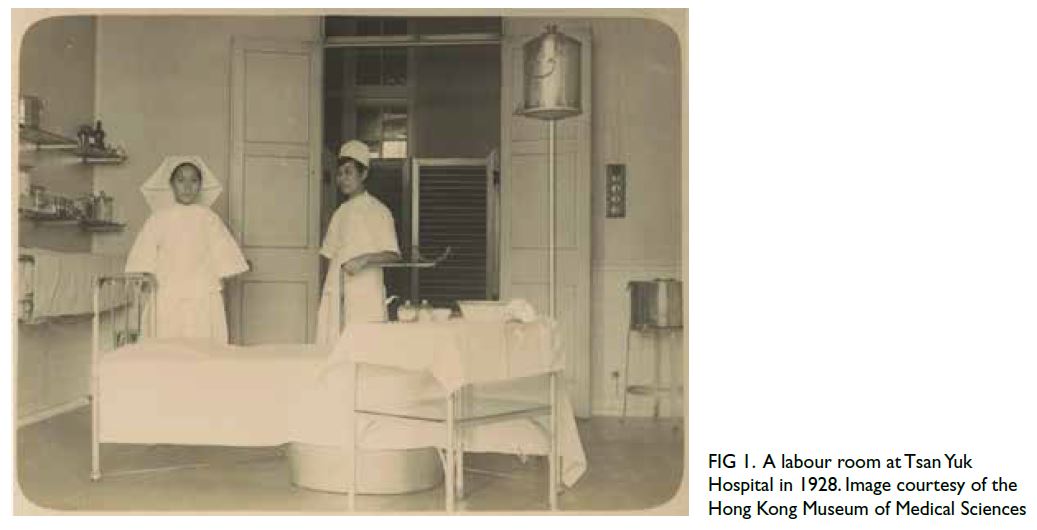

Figure 1. A labour room at Tsan Yuk Hospital in 1928. Image courtesy of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences

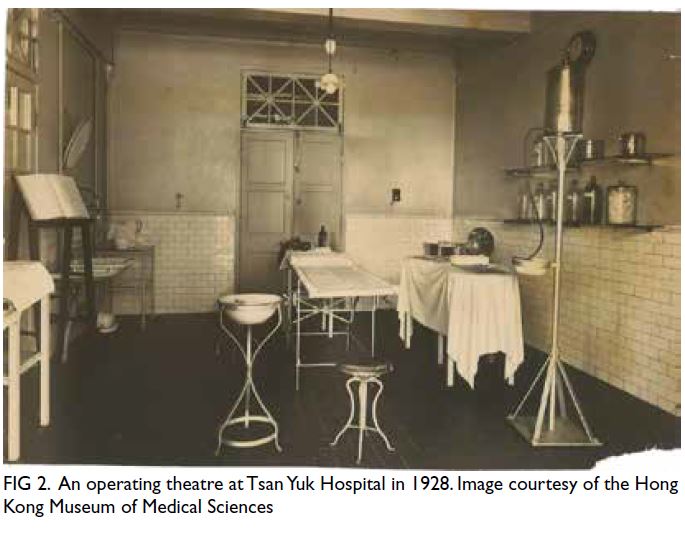

Figure 2. An operating theatre at Tsan Yuk Hospital in 1928. Image courtesy of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences

The 1920s labour room (Fig 1) was minimalist

compared to today’s. The focal point was a simple

bed, positioned in the room’s centre. Wall-mounted

shelves held glass jars and metal containers, likely filled with medications and consumables. Next to

the bed, there was a table upon which sat multiple

bowls. Most consumables were placed in a bowl. The

bowl itself would be used by one patient at a time

and disinfected between patients. The special metal

container held up by a pole next to the bed is thought

to be a water tank storing sterilised water, but this

has not been confirmed.

Figure 3 shows a current labour room in a

new Kwong Wah Hospital building that has been

operational since 2024. Unlike the relatively bare

1920s room, the modern labour room boasts

equipment to ensure the baby’s safety, including

a cardiotocography machine to monitor fetal

heartbeat, an incubator to keep the baby warm,

and a resuscitaire in case of neonatal resuscitation.

The electric bed can be adjusted for height and

dismantled in seconds for the mother to transition

into the lithotomy position. Mounted to the wall,

there is an emergency alarm, a suction device and

equipment providing oxygen or nitrous oxide. Bowls are obsolete as most consumables are now placed in

single-use plastic containers.

Figure 2 captures an operating theatre at Tsan

Yuk Hospital in the 1920s, while Figure 4 features

an operating theatre on the labour ward at Kwong

Wah Hospital. A hundred years ago, the theatre was

equipped with basic instruments and had limited

lighting. There were no anaesthetic machines or

monitoring equipment. Seen side by side, one can

appreciate the rapid development of medicine in

Hong Kong.

There were 1109 admissions to Tsan Yuk

Hospital and 537 admissions to the Government

Civil Hospital in 1928.2 In those days, before safe

anaesthesia and antibiotics, caesarean delivery

carried a very high risk. That year, only two caesarean

sections were performed in which both the women

and their babies survived.2 The low maternal

morbidity rate at Tsan Yuk Hospital in the 1920s can

be attributed to the enhanced hygiene resulting from

each patient having their own pan, bowl and chamber

pot at each bed, as Prof Tottenham reported.2

The introduction of anaesthesia changed the

labouring experience. In the 1920s, most mothers

laboured without any analgesia. However, inspired

by the use of rectal ether during their visit to the New

York Lying-In Hospital in the United States, doctors

at Tsan Yuk Hospital tested colonic ether on 27

primiparous women.2 The medication was a mixture

of olive oil, ether and paraldehyde, administered via

an enema at the start of labour. When the cervix

was almost fully dilated, an additional small dose

of morphine was injected through a rectal tube

into the colon. Pure olive oil would then be injected

into the tube, followed by more olive oil and ether,

with or without paraldehyde. Once labour ended,

the rectum was washed. Nowadays, most expectant

mothers would reject such a form of pain relief.

In fact, colonic ether is no longer used to alleviate

labour pain. Instead, many other pharmacological

and non-pharmacological options, such as an

epidural, nitrous oxide inhalation, injections and

childbirth massage, are available to manage the pain

of childbirth.

Prior to the introduction of Western medicine

in the late 19th century, traditional Chinese

medicine was mainstream.3 Most women chose to

deliver their babies at home and only presented at

hospital after exhausting their traditional Chinese

midwives’ treatment options.3 After giving birth,

women typically returned to their communities as

soon as possible.3 Yet this started to change around

1928 as Western medicine gained greater public

acceptance. According to Prof Tottenham’s report,2

more than 90% of postpartum patients stayed at

Tsan Yuk Hospital for a week, whereas a few years

prior, nursing staff were to be congratulated if

patients stayed for more than 3 days after delivery. A longer postpartum stay in hospital was considered

a safe practice in the 1920s, when sepsis rates were

high and most homes lacked a clean water supply.

The pendulum swung back in the 1980s, and early

discharge from hospital became the norm, owing

to improved housing and an increased demand for

maternity beds due to the influx of Vietnamese and mainland Chinese immigrants.3

Since its inception over a century ago, Tsan

Yuk Hospital has provided the highest-quality

obstetric care in Hong Kong. As we reflect on Tsan

Yuk Hospital’s remarkable legacy, may its history

continue to guide and inspire the future of maternal

care in Hong Kong.

References

1. Law BM, Hui PW. Tsan Yuk Hospital: a century of dedicated obstetrical service. Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2023;23:135-9. Crossref

2. Tottenham RE, Pillai DK, Lam SK, Lai PC. Clinical report of the Tsan Yuk Hospital and of the Maternity Bungalow, Government Civil Hospital. Caduceus 1928;7:194-219.

3. Chow AW. Metamorphosis of Hong Kong midwifery. Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2001;1:72-80.