Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 21 May 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Roles of unmet supportive care needs, supportive

cancer care service disruptions, and COVID-19–related perceptions in psychological distress among recently diagnosed breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong

Nelson CY Yeung, PhD1; Stephanie TY Lau, BSSc1; Winnie WS Mak, PhD2; Cecilia Cheng, PhD3; Emily YY Chan, PhD1; Judy YM Siu, PhD4; Polly SY Cheung, PhD5

1 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Psychology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Psychology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Applied Social Sciences, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Hong Kong Breast Cancer Foundation, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Nelson CY Yeung (nelsonyeung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Receiving a cancer diagnosis and

living with breast cancer can be particularly stressful

during pandemic situations. This study examined

how cancer care service disruptions, unmet

supportive care needs (SCNs), and coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related perceptions were

associated with psychological distress among Hong

Kong breast cancer survivors (BCS) during the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: A total of 209 female BCS diagnosed since

January 2020 (ie, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic

in Hong Kong) were recruited from the Hong Kong

Breast Cancer Registry to complete a cross-sectional

survey measuring the aforementioned variables.

Results: Multivariable logistic regression analysis

indicated that unmet physical/daily living needs (odds

ratio [OR]=1.03; P=0.002), unmet psychological

needs (OR=1.06; P<0.001), and perceived severity

of COVID-19–related health consequences in BCS

(OR=1.67; P=0.02) were significantly associated

with moderate-to-severe psychological distress.

However, cancer treatment/supportive care service

disruptions, fear of COVID-19, and unmet SCNs

in patient care/health system information/sexual

domains were not significant contributors (P=0.77-0.89).

Conclusion: Half of the BCS in Hong Kong

experienced substantial psychological distress during

the pandemic. Survivors with higher levels of unmet SCNs in physical/daily living and psychological

domains, as well as those with greater perceived

severity of COVID-19–related health consequences,

were more likely to experience moderate-to-severe

psychological distress. These findings suggest that

efforts to address specific unmet SCNs and risk

perceptions are important for reducing psychological

distress among BCS during pandemic situations.

New knowledge added by this study

- At least 50% of breast cancer survivors (BCS) in Hong Kong experienced a moderate-to-severe level of psychological distress during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

- Unmet needs in physical/daily living and psychological domains were associated with moderate-to-severe psychological distress among local BCS.

- Perceived COVID-19 severity, but not fear of COVID-19, was associated with moderate-to-severe psychological distress among local BCS.

- To address the physical and psychological needs of BCS, healthcare providers should consider how telemedicine services can provide remote support for symptom management and psychological counselling.

- The provision of up-to-date educational materials can help alleviate distress and risk perceptions related to COVID-19.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

pandemic has had a broad public health impact on

global populations. Pandemic-control measures

(eg, social distancing regulations and changes in

hospital services) have affected both the general

population and individuals with chronic diseases

(including cancer survivors).1 A recent meta-analysis

found that 53.9% of cancer patients (n=27

590) experienced high levels of distress during the

COVID-19 pandemic2; breast cancer survivors

(BCS) reported highest prevalence of post-traumatic

stress symptoms (52.3%) among all groups of cancer

patients.2 In Hong Kong, 40% of cancer survivors

reported feeling anxious and depressed during

COVID-19.3 However, factors associated with

psychological distress among local BCS during the

pandemic have been understudied.

After completion of active treatment, BCS

require a range of supportive cancer care services for

rehabilitation. To prioritise resources for managing

COVID-19, some oncology services were postponed

in Hong Kong.4 Among a heterogeneous sample

of cancer survivors in Hong Kong,3 <10% reported

that the COVID-19 pandemic had affected their

hospital treatments or follow-ups. Despite this

low prevalence, the potential negative impacts of such disruptions on cancer survivors’ well-being

should not be ignored. A systematic review found

that delays or changes in treatment plans were

associated with high levels of psychological distress,

above and beyond the contributions of other socio-demographic

factors.5 Similarly, BCS in the United

Kingdom who experienced disrupted oncology

services reported worse emotional well-being.6 In

China, a 3-week treatment delay was significantly

associated with increased psychological symptoms

among BCS.7 Based on these findings, we speculated

that cancer treatment and supportive care service

disruptions would be associated with greater

psychological distress among BCS in Hong Kong.

Given that cancer survivors are more

aware of the risks of infection compared with the

general population,8 their emotional reactions and

perceptions towards COVID-19 also contribute

to their well-being. Due to the rapidly changing

pandemic situations caused by different variants

of the COVID-19 virus, cancer survivors tend to

experience fear of contracting COVID-19 and

express concerns about the severity of its negative

health impacts on cancer prognosis.9 10 Based

on a review of 51 studies (19.5% conducted in

Asia), COVID-19–related fear and worries were

associated with psychological distress among cancer

survivors.11 However, a recent study in Hong Kong

showed that 49.7% of cancer survivors did not feel

worried about contracting COVID-19,3 and they did

not consider themselves to experience more negative

consequences of contracting COVID-19 compared

with the general population.12 Whether COVID-19–related fear and risk perceptions are associated with

psychological distress among BCS in Hong Kong has

yet to be explored.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unmet

supportive care needs (SCNs) among BCS. According

to Fitch’s Supportive Care Needs Framework,13 a

medical diagnosis affects people’s abilities to meet

their own needs across life domains; unmet needs

may result in worse adjustment outcomes. It is

common for cancer survivors to report physical,

psychological, social, and health system–related

unmet needs during COVID-19.14 A longitudinal

survey of Asian and Asian American cancer survivors

revealed a significant increase in psychological and

healthcare access needs during COVID-19.15 In

Hong Kong, higher levels of unmet SCNs were

identified in the health system/information,

psychological, and patient care/support domains

among cancer survivors during COVID-19.3 In

Australia, unmet SCNs were associated with greater

psychological distress among haematological

and gynaecological cancer survivors.16 However,

research examining the associations between unmet

SCNs and BCS’ psychological distress has been

sparse.

This study examined factors associated with

psychological distress among Hong Kong BCS during

COVID-19. We hypothesised that different domains

of unmet SCNs, disruptions in cancer treatment

and supportive cancer care services, increased fear

of COVID-19, and a stronger belief that COVID-19

would cause more severe health consequences for

BCS (compared with the general population) were

associated with greater psychological distress.

Methods

Prospective participants were recruited from

the Hong Kong Breast Cancer Registry, the most

representative monitoring system for BCS in Hong

Kong.17 Based on the cancer registry data, those

fulfilling the inclusion criteria were invited to

participate in a cross-sectional survey. Breast cancer

survivors eligible for the study were required to be:

≥18 years old, diagnosed with stages 0 to III cancer

since January 2020, in active treatment, able to read

Chinese and communicate in Cantonese, and able to

provide informed consent.

Among 946 BCS contacted, 409 were

unreachable, 23 were ineligible, and 227 were

uninterested in the study. With verbal consent

given over the phone, those who were eligible and

interested in the study (n=287) received a mail

package enclosing a cover letter explaining the study

details, a consent form, a questionnaire packet, a

stamped return envelope, and a thank-you card. After

they had provided consent, participants completed

the survey at home. Participants were compensated

with supermarket vouchers (worth HK$100) for

their time upon returning the completed survey. The

study was conducted between June and December

2022. Overall, 209 completed surveys were returned

(from 287 sent), yielding a completion rate of 72.8%.

Measurement

Psychological distress

The one-item National Comprehensive Cancer

Network Distress Thermometer was used to

assess participants’ psychological distress over

the past week.18 On an 11-point Likert scale, the

thermometer ranged from 0 (no distress) to 10

(extreme distress).19 A higher score indicated a

higher level of psychological distress. A cut-off point

of ≥4 indicated moderate-to-severe distress.20 The

Chinese version of the Distress Thermometer has

demonstrated reliability and validity among Chinese

cancer patients.21

Cancer treatment and supportive cancer care

service disruptions during coronavirus disease

2019

Participants’ experiences of any postponement or

cancellation of various types of cancer treatments (eg, surgery and adjuvant therapies) and supportive

cancer care services (eg, psychological counselling

and peer support groups) during COVID-19 were

measured (no=0, yes=1).

Supportive care needs

The Chinese version of the 34-item Short-Form

Supportive Care Needs Questionnaire was used to

measure five domains of SCNs (namely, physical/daily living, psychological needs, patient care and

support, sexuality, and health system/information

needs) over the past month. On a five-point scale (no

need–not applicable, no need–satisfied, low need,

moderate need, high need), items were scored using

standardised guidelines.22 Higher scores indicated

higher levels of unmet SCNs. The scale has shown

reliability and validity among Hong Kong cancer

survivors.3 22

Fear of coronavirus disease 2019

The Chinese version of the seven-item Fear

of COVID-19 Scale was adapted to measure

participants’ fear of COVID-19.23 On a five-point

scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree),

a higher mean score indicated greater fear of

COVID-19 (eg, “My heart races or palpitates when I

think about getting COVID-19”; Cronbach’s α=0.88).

The scale has demonstrated reliability and validity in

a Chinese general population.23

Perceived severity of consequences of coronavirus

disease 2019 on breast cancer survivors

A single item was developed to measure participants’

perception of the severity of COVID-19 health

consequences for BCS (ie, “COVID-19 can cause

more severe health consequences in BCS than in the

general population”). Responses were recorded on

a five-point scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly

agree); higher scores indicated greater perceived

severity.

Clinical and socio-demographic characteristics

Participants self-reported the following

characteristics: (1) socio-demographic information;

(2) treatment-related variables (surgery undergone,

treatments being received or completed, and time

since last treatment); and (3) breast cancer–related

variables (eg, stage at diagnosis and time since

diagnosis).

Planned analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

among the variables were computed. Multivariable

logistic regressions were used to examine

associations between independent variables

and moderate-to-severe levels of psychological distress (binary-coded), based on the suggested

Distress Thermometer cut-off of ≥4. Simple logistic

regression analysis was used to assess how individual

variables (including socio-demographic/cancer-related

variables, cancer treatment/supportive

cancer care service disruptions, unmet SCNs, fear

of COVID-19, and COVID-19 risk perception)

were associated with psychological distress. Odds

ratios (ORs) were obtained by separately fitting each

variable against psychological distress.24 Significant

variables in the simple analyses were then entered

into a multivariable logistic regression model using

the enter method. These analyses were performed

using SPSS (Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], US). P values <0.05 were considered

statistically significant.

Sample size calculation

Based on prior studies regarding BCS’ psychological

distress,24 25 we assumed a similar prevalence of

30% for moderate-to-severe levels of psychological

distress in our target population. With α=0.05 (two-tailed)

and a statistical power of 80%, a sample

size of 203 would be sufficient to detect an OR of

1.56 for the key independent variables (G*Power

version 3.1.2).26 The current sample size (n=209)

was sufficient to detect the expected effect sizes with

adequate statistical power.

Results

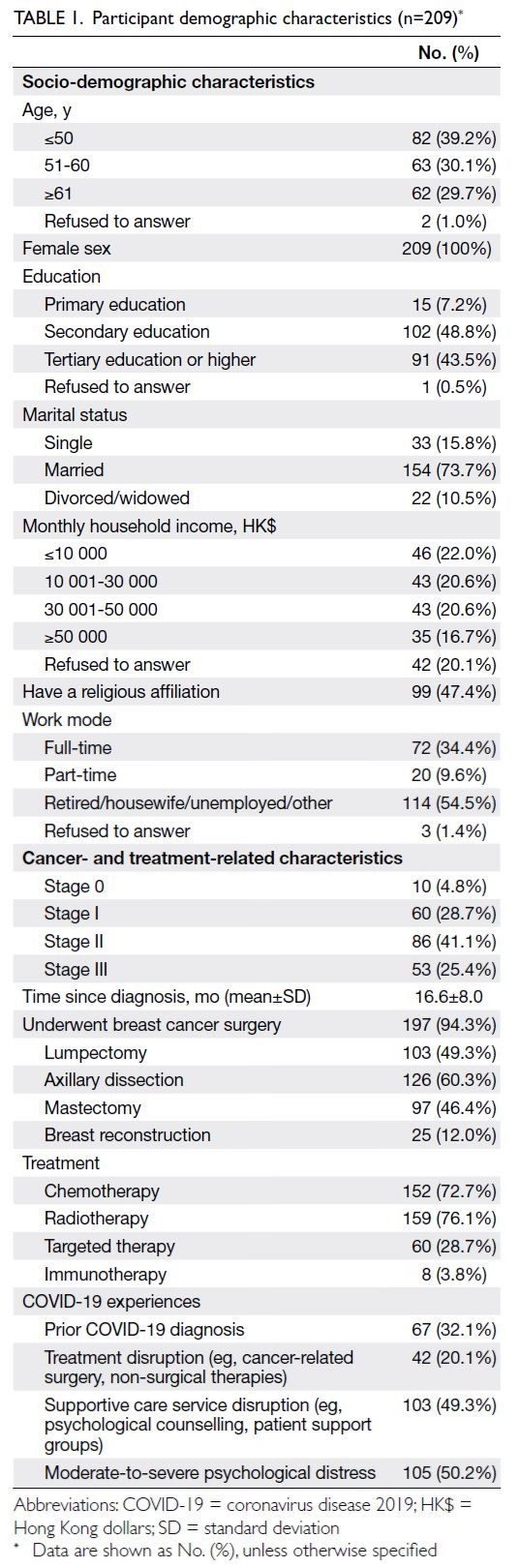

Participant characteristics

Among the 209 participants, 69.3% were aged ≤60

years. Regarding cancer-related characteristics,

4.8%, 28.7%, 41.1%, and 25.4% were diagnosed

with Stage 0, Stage I, Stage II, and Stage III breast

cancer, respectively. Most participants (94.3%) had

undergone breast cancer surgery. Most had also

received chemotherapy (72.7%) and radiotherapy

(76.1%). The average time since diagnosis was 16.6

months (standard deviation=8.00). During COVID-19, 32.1% of participants had a prior diagnosis of

COVID-19; 20.1% experienced cancer treatment

disruptions (eg, surgery/adjuvant therapies); and

49.3% experienced supportive cancer care service

disruptions (eg, psychological counselling, patient

support groups). Based on a Distress Thermometer

score ≥4, 50.2% of participants reported a moderate-to-severe level of psychological distress (Table 1).

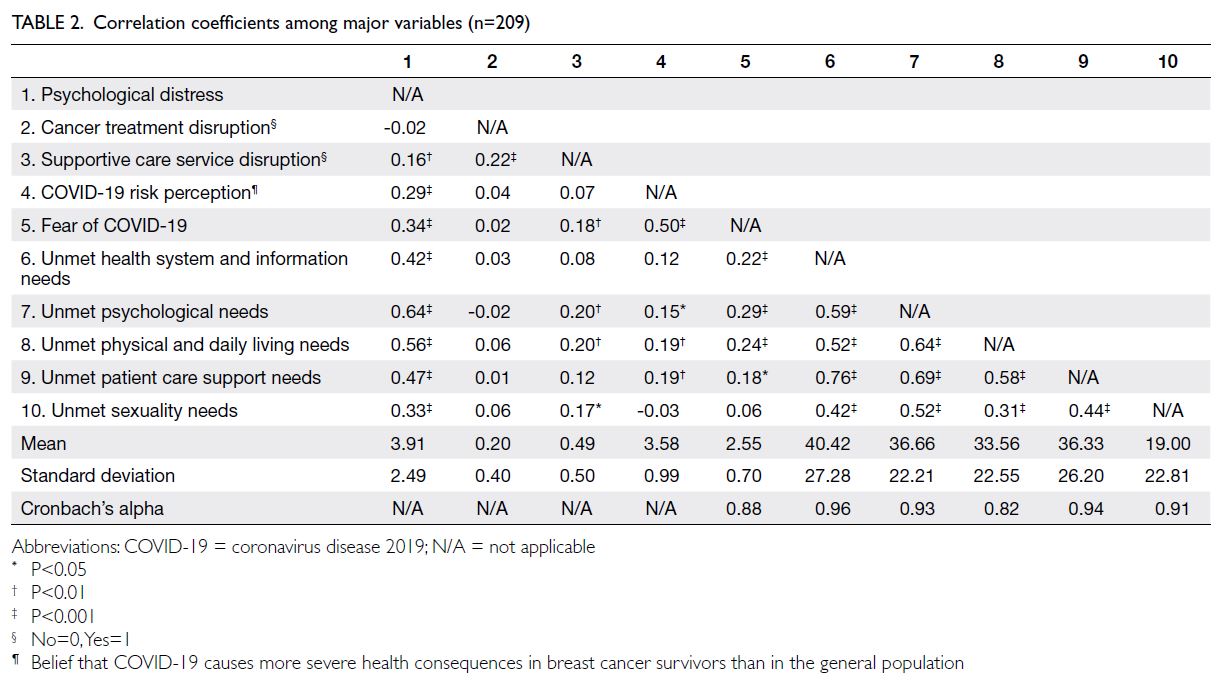

Correlations between major variables and

psychological distress

Based on the correlation analysis results (Table 2), participants who had experienced supportive

cancer care service disruption, perceived greater

fear of COVID-19, and held a stronger belief that

COVID-19 causes more severe health consequences

in BCS tended to report increased psychological distress (sample correlation coefficients=0.16-0.34;

all P<0.01). All five domains of unmet SCNs were

associated with increased psychological distress

(sample correlation coefficients=0.33-0.64; all P<0.001).

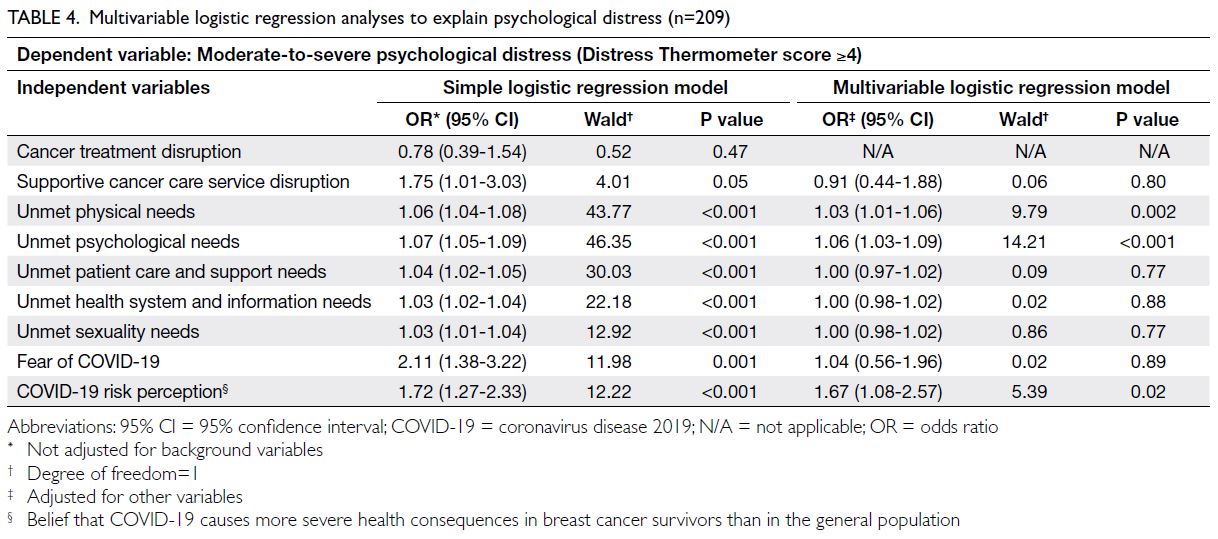

Logistic regression analyses

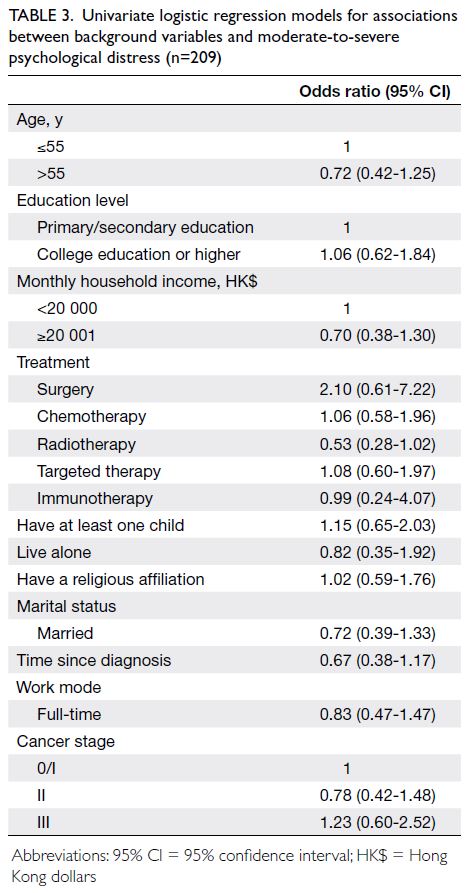

In the simple logistic regression analyses (Table 3), no background variables showed significant

associations with psychological distress; accordingly,

adjustments for those variables were not included

in the final multivariable regression model. On the

other hand, all domains of unmet SCNs (ORs=1.03-1.07; all P<0.001), cancer supportive care service

disruption (OR=1.75; P=0.05), fear of COVID-19

(OR=2.11; P=0.001), and the perception that

COVID-19 causes more severe health consequences

in BCS (OR=1.72; P<0.001) were associated with

moderate-to-severe psychological distress (Table 4). The multivariable logistic regression results

indicated that only unmet physical needs (OR=1.03;

P=0.002), unmet psychological needs (OR=1.06;

P<0.001), and perceived severity of COVID-19–related health consequences in BCS (OR=1.67;

P=0.02) were associated with moderate-to-severe

psychological distress (Table 4).

Table 3. Univariate logistic regression models for associations between background variables and moderate-to-severe psychological distress (n=209)

Discussion

At least 50% of BCS in Hong Kong experienced

a moderate-to-severe level of distress during COVID-19. This prevalence was comparable to

that of gynaecological cancer survivors in Turkey,27

but lower than that of sarcoma patients in Italy.28

Discrepancies in prevalence might be attributed to

varied pandemic situations across regions, including

differences in survey periods, cancer types, and

specific pandemic-control measures. Future

research could investigate how these factors jointly

contribute to BCS’ psychological distress. Among the

studied variables, multivariable logistic regression

analysis revealed that higher levels of unmet SCNs

in physical and psychological domains, along with

a stronger belief that COVID-19 could cause more

severe health consequences in BCS, were associated

with greater psychological distress among BCS in

Hong Kong.

Supportive care service disruption was

associated with breast cancer survivors’

psychological distress

We found that 20.1% and 49.3% of BCS experienced

cancer treatment and supportive cancer care

service disruptions, respectively, during COVID-19.

Only the disruption of supportive cancer care

services (but not cancer treatments) demonstrated

a significant univariate association with moderate-to-severe psychological distress. Previously, cancer

care service disruptions during COVID-19 were

associated with worse psychological outcomes

among BCS in the United Kingdom,6 Canada,29 and Ireland.30 Given that disruptions of supportive

cancer care services (but not cancer treatments)

were positively associated with unmet SCNs, the

absence of timely supportive care might make coping

with and living with cancer particularly difficult

during COVID-19.11 However, supportive cancer

care service disruption was no longer significant

in multivariable logistic regression analyses when

other independent variables were considered. This

finding implies that more proximal factors related to

BCS’ daily lives and challenges (eg, different domains

of unmet SCNs) had relatively greater prominence

in explaining psychological distress among BCS in

Hong Kong during COVID-19.

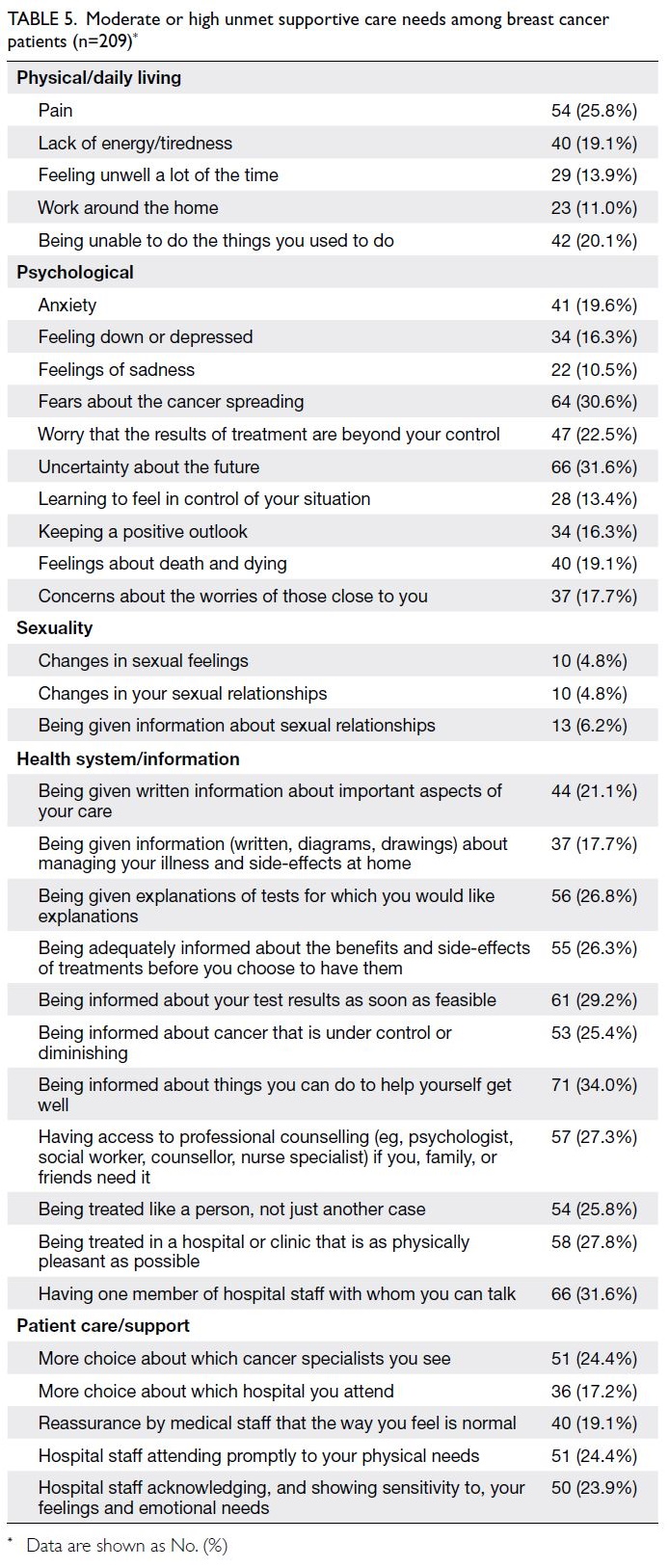

Unmet supportive care needs in relation

to breast cancer survivors’ psychological distress

Breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong reported

moderate levels of unmet SCNs across different

domains, with the highest score in the health system/information domain and the lowest score in the

sexuality domain (Table 5). These levels of unmet

SCNs were comparable to those reported by other

local cancer survivors in 2021.3 Our findings

showed that all five domains of unmet SCNs were

associated with moderate-to-severe psychological

distress, but only unmet SCNs in the psychological

and physical/daily living domains constituted

significant contributors in the final multivariable

logistic regression model (Table 4). These findings

were similar to a study conducted among survivors

of mixed cancer types (56.7% diagnosed within the

previous year) in Turkey.31 According to that study,31

conducted during COVID-19, all domains of unmet SCNs were correlated with depression/anxiety, but

only unmet SCNs in the psychological and physical/daily living domains independently contributed to

depression/anxiety in the multivariable analysis. In

contrast, among cancer survivors in Jordan (77%

diagnosed ≥6 years prior), all domains of unmet SCNs

during COVID-19 were independently associated

with quality of life.32 Given that our participants

were recently diagnosed BCS (with an average

time since diagnosis of 16.6 months; all diagnosed

after the COVID-19 pandemic began), they were

still in the process of coping with the reality of the

cancer diagnosis, the discomfort and side-effects

of treatment, uncertainties about the future, and

potential cancer recurrences. Considering the time

since diagnosis, the relative contributions of SCNs in

the psychological and physical/daily living domains

to psychological distress were particularly strong

among recently diagnosed BCS during COVID-19.

Coronavirus disease 2019–related risk

perception was associated with psychological distress

Fear of COVID-19 was associated with greater

psychological distress only in the simple analysis,

but not in the multivariable regression model.

Previously, fear of COVID-19 was associated

with greater psychological distress among cancer

survivors in the US33 and the general population in

Hong Kong34 during earlier phases of the COVID-19

pandemic in 2020 to 2021. Due to Hong Kong’s

unique experiences in successfully managing

prior pandemics (eg, the severe acute respiratory

syndrome and the H1N1 pandemics),35 pandemic

fatigue (ie, a state of emotional and physical

exhaustion resulting from prolonged anti-pandemic

measures) was observed during the fourth and fifth

waves of the pandemic in Hong Kong (2021-2022).36

Such fatigue was reflected in the lower levels of fear

of COVID-19 (ie, affective and physiological states

of anxiety and fear towards COVID-19) among our

sample surveyed in 2022, compared with the general

population surveyed in early 2021,34 using the same

measurement. This finding might explain why the

contribution of fear of COVID-19 to psychological

distress among local BCS was weaker than expected.

Conversely, we found that the perceived

severity of the health consequences of COVID-19

for BCS was a stronger contributor to psychological

distress than fear of COVID-19. Cancer and its

treatments (eg, chemotherapy) can weaken patients’

immune systems, and it is common for BCS to

believe that being immunocompromised might lead

to more severe health consequences if they contract

COVID-19.1 Risk perception has been associated

with coping behaviours. For example, a recent

study found that risk perception about COVID-19

was a stronger contributor to information-seeking behaviour among the general population in Hong

Kong than among their counterparts in China and

Taiwan.37 We expected that this phenomenon would

also be apparent among Hong Kong BCS. However,

health information about COVID-19 may not

always be tailored for cancer survivors or effectively

communicated through local mass media,1 which

could be associated with psychological distress

among BCS. To alleviate such COVID-19–related

risk perceptions, we recommend that health

organisations tailor health information and provide

counselling for cancer survivors through alternative

platforms (eg, social media and online forums).

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, given

its cross-sectional design, it could not establish

causal relationships among the variables. Cancer

survivors’ risk perceptions about COVID-19 and

unmet SCNs are likely to change throughout the

course of their cancer journey. Future studies could

utilise longitudinal designs to better understand

the temporal relationships among variables and

psychological distress. Second, although the

Hong Kong Breast Cancer Registry is the most

comprehensive registry for BCS in Hong Kong, it

does not cover the entire BCS population due to its

voluntary enrolment system. The generalisability of

the findings to BCS in other countries with different

healthcare systems and pandemic situations should

be interpreted with caution. Third, other important

independent variables might contribute to BCS’

psychological distress. Studies have revealed that

additional daily COVID-19 stressors (eg, increased

responsibilities at home and difficulties obtaining

daily necessities) and coping strategies (eg,

catastrophising) may play key roles in explaining

psychological distress among cancer survivors.12 29

The inclusion of such variables could further improve

the explanatory power of the regression model.

Fourth, to reduce participant burden, we measured

risk perceptions related to COVID-19 using a self-developed

item. Specifically developed items are

commonly used as predictors of psychological

outcomes to capture nuances in the local COVID-19 context.38 However, researchers are encouraged

to confirm our findings using fully validated

instruments for the measurement of COVID-19 risk

perceptions.

Implications

This study highlights the importance of addressing

BCS’ unmet SCNs in the physical/daily living

and psychological domains, as well as their

risk perceptions of COVID-19, in relation to

psychological distress during the pandemic. To

address physical/daily living needs, survivors might need to engage in self-monitoring of health (eg,

reporting symptoms and metrics to healthcare

providers through patient portals). Psychological

well-being should be regularly monitored, and

communication between providers and survivors

should be maintained through virtual means. In

addition to information about cancer symptom

management, survivors should be provided with

accessible mental health services that can support

them in coping with the emotional impacts of their

diagnosis and treatment.39 Regarding COVID-19

risk perception, it may be beneficial to offer accurate

and up-to-date educational materials explaining

BCS’ risks associated with COVID-19 and how

they can protect themselves. Research suggests

that telehealth can empower survivors and provide

strategies for coping during unprecedented times.

A recent study in Iran indicated that a tele-nursing

intervention—including supportive telephone

calls with explanations about cancer, treatment

side-effects, symptom management, and self-care—reduced unmet SCNs among Iranian cancer

survivors undergoing chemotherapy.40 Researchers

should explore the applicability of such service

models in Hong Kong and other regions.

Conclusion

Half of BCS in Hong Kong experienced a moderate-to-severe level of psychological distress during

COVID-19. Efforts to address unmet SCNs in the

physical/daily living and psychological domains,

manage risk perceptions regarding health

consequences of COVID-19, and provide supportive

cancer care services through alternative modes

might help alleviate psychological distress among

BCS in future pandemic situations.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: NCY Yeung, STY Lau.

Analysis or interpretation of data: NCY Yeung, STY Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: NCY Yeung, STY Lau.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: NCY Yeung.

Acquisition of data: NCY Yeung, STY Lau.

Analysis or interpretation of data: NCY Yeung, STY Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: NCY Yeung, STY Lau.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: NCY Yeung.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research was supported by the Health and Medical

Research Fund of the Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR

Government (Ref No.: 18190061). The funder had no role in

the study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation, or

manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of

Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2021.286) and the

Hong Kong Breast Cancer Foundation. Informed consent

was obtained from all individual participants included in the

study.

References

1. Huang J, Wang HH, Zheng ZJ, Wong MC. Impact of the

COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Hong Kong Med J

2022;28:427-9. Crossref

2. Zhang H, Xu H, Zhang Z, Zhang Q. Efficacy of virtual

reality–based interventions for patients with breast cancer

symptom and rehabilitation management: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022;12:e051808. Crossref

3. Cheung DS, Takemura N, Lui HY, et al. A cross-sectional

study on the unmet supportive care needs of cancer

patients under the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer Care Res

Online 2022;2:e028. Crossref

4. Koczwara B. Cancer survivorship care at the time of the

COVID-19 pandemic. Med J Aust 2020;213:107-8.e1. Crossref

5. Prabani KI, Damayanthi HD. Quality of life, anxiety,

depression and psychological distress in patients with

cancer during the COVID 19 pandemic: a systematic

review. Intl Health Trends Perspect 2022;2:51-66. Crossref

6. Swainston J, Chapman B, Grunfeld EA, Derakshan N.

COVID-19 lockdown and its adverse impact on

psychological health in breast cancer. Front Psychol

2020;11:2033. Crossref

7. Wang Y, Yang Y, Yan C, et al. COVID-induced 3 weeks’

treatment delay may exacerbate breast cancer patient’s

psychological symptoms. Front Psychol 2022;13:1003016. Crossref

8. Slivjak ET, Fishbein JN, Nealis M, Schmiege SJ, Arch JJ.

Cancer survivors’ perceived vulnerability to COVID-19 and

impacts on cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to

the pandemic. J Psychosoc Oncol 2021;39:366-84. Crossref

9. Glidden C, Howden K, Romanescu RG, et al. Psychological

distress and experiences of adolescents and young adults

with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional

survey. Psychooncology 2022;31:631-40. Crossref

10. Shay LA, Allicock M, Li A. “Every day is just kind of

weighing my options.” Perspectives of young adult cancer

survivors dealing with the uncertainty of the COVID-19

global pandemic. J Cancer Surviv 2022;16:760-70. Crossref

11. Muls A, Georgopoulou S, Hainsworth E, et al. The

psychosocial and emotional experiences of cancer patients

during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review.

Semin Oncol 2022;49:371-82. Crossref

12. Ng DW, Chan FH, Barry TJ, et al. Psychological distress

during the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

pandemic among cancer survivors and healthy controls.

Psychooncology 2020;29:1380-3. Crossref

13. Fitch MI. Supportive Care Framework [in English, French].

Can Oncol Nurs J 2008;18:6-24. Crossref

14. Legge H, Toohey K, Kavanagh PS, Paterson C. The unmet

supportive care needs of people affected by cancer during

the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review. J Cancer

Surviv 2023;17:1036-56. Crossref

15. Wang K, Ma C, Li FM, et al. Patient-reported supportive

care needs among Asian American cancer patients.

Support Care Cancer 2022;30:9163-70. Crossref

16. Zomerdijk N, Jongenelis M, Short CE, Smith A, Turner J,

Huntley K. Prevalence and correlates of psychological

distress, unmet supportive care needs, and fear of cancer

recurrence among haematological cancer patients

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer

2021;29:7755-64. Crossref

17. Hong Kong Breast Cancer Foundation. Hong Kong Breast

Cancer Registry Report No. 11. 2019. Available from:

https://www.hkbcf.org/en/our_research/main/468/. Accessed 26 May 2023.

18. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Distress

Thermometer Tool Translations. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/global/what-we-do/distress-thermometer-tool-translations. Accessed 10 Jul 2023.

19. Ownby KK. Use of the Distress Thermometer in clinical

practice. J Adv Pract Oncol 2019;10:175-9. Crossref

20. Wood DE. National Comprehensive Cancer Network

(NCCN) clinical practice guidelines for lung cancer

screening. Thorac Surg Clin 2015;25:185-97. Crossref

21. Thapa S, Sun H, Pokhrel G, Wang B, Dahal S, Yu S.

Performance of Distress Thermometer and associated

factors of psychological distress among Chinese cancer

patients. J Oncol 2020;2020:3293589. Crossref

22. Au A, Lam W, Tsang J, et al. Supportive care needs in Hong

Kong Chinese women confronting advanced breast cancer.

Psychooncology 2013;22:1144-51. Crossref

23. Chi X, Chen S, Chen Y, et al. Psychometric evaluation of

the Fear of COVID-19 Scale among Chinese population.

Int J Ment Health Addict 2022;20:1273-88. Crossref

24. Vanni G, Materazzo M, Santori F, et al. The effect of

coronavirus (COVID-19) on breast cancer teamwork: a

multicentric survey. In Vivo 2020;34(3 Suppl):1685-94. Crossref

25. Pang L, Yao S, Li W, Jing Y, Yin X, Cheng H. Impact of the

CALM intervention on breast cancer patients during the

COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer 2023;31:121. Crossref

26. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power

analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and

regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:1149-60. Crossref

27. Yavuz AD, Dolanbay M, Akyüz Çim EF, Dişli Gürler A,

Cündübey CF. Analysis of distress in patients with

gynecological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a

telephone survey. J Clin Obstet Gynecol 2022;32:93-9. Crossref

28. Onesti CE, Vari S, Minghelli D, et al. Quality of life and

emotional distress in sarcoma patients diagnosed during

COVID-19 pandemic: a supplementary analysis from the

SarCorD study. Front Psychol 2023;14:1078992. Crossref

29. Massicotte V, Ivers H, Savard J. COVID-19 pandemic

stressors and psychological symptoms in breast cancer

patients. Curr Oncol 2021;28:294-300. Crossref

30. Myers C, Bennett K, Kelly C, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on

health care and quality of life in women with breast cancer.

JNCI Cancer Spectr 2023;7:pkad033. Crossref

31. Erdoğan Yüce G, Döner A, Muz G. Psychological distress

and its association with unmet needs and symptom burden

in outpatient cancer patients: a cross-sectional study.

Semin Oncol Nurs 2021;37:151214. Crossref

32. Al-Omari A, Al-Rawashdeh N, Damsees R, et al.

Supportive care needs assessment for cancer survivors at a

comprehensive cancer center in the Middle East: mending

the gap. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:1002. Crossref

33. Caston NE, Lawhon VM, Smith KL, et al. Examining

the association among fear of COVID-19, psychological

distress, and delays in cancer care. Cancer Med 2021;10:8854-65. Crossref

34. Chair SY, Chien WT, Liu T, et al. Psychological distress, fear

and coping strategies among Hong Kong people during the

COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol 2023;42:2538-57. Crossref

35. Matus K, Sharif N, Li A, Cai Z, Lee WH, Song M. From

SARS to COVID-19: the role of experience and experts

in Hong Kong’s initial policy response to an emerging

pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2023;10:9. Crossref

36. Leung HT, Gong W, Sit SM, et al. COVID-19 pandemic

fatigue and its sociodemographic and psycho-behavioral

correlates: a population-based cross-sectional study in

Hong Kong. Sci Rep 2022;12:16114. Crossref

37. Liu R, Huang YC, Sun J. The media-mediated model of

information seeking behavior: a proposed framework in

the Chinese culture during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Commun 2024;39:3468-79. Crossref

38. Yeung NC, Tang JL, Hui KH, Lau ST, Cheung AW,

Wong EL. “The light after the storm”: psychosocial

correlates of adversarial growth among nurses in Hong

Kong amid the fifth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Psychol Trauma 2024;16:989-98. Crossref

39. Thompson CA, Overholser LS, Hébert JR, Risendal BC,

Morrato EH, Wheeler SB. Addressing cancer survivorship

care under COVID-19: perspectives from the cancer

prevention and control research network. Am J Prev Med

2021;60:732-6. Crossref

40. Ebrahimabadi M, Rafiei F, Nejat N. Can tele-nursing

affect the supportive care needs of patients with cancer

undergoing chemotherapy? A randomized controlled trial

follow-up study. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:5865-72. Crossref