Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 28 Jan 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Early prenatal detection of autosomal dominant

skeletal dysplasia using first-trimester ultrasound and cell-free fetal DNA screening: three case reports

Ye Cao, PhD, FACMG1,2; Yvonne KY Cheng, MSc (Medical Genetics), FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; TY Leung, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1,2; Shuwen Xue, MPhil, PhD1,2; Yuting Zheng, MPhil1,2; KW Choy, MSc (Med), PhD1,2; Winnie CW Chu, MD, FHKAM (Radiology)3; HM Luk, MD, FHKAM (Paediatrics)4; KM Law, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; YH Ting, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Shenzhen Research Institute, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China

3 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Clinical Genetics, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr YH Ting (tingyh@cuhk.edu.hk)

Case presentations

Case 1 (Family 1)

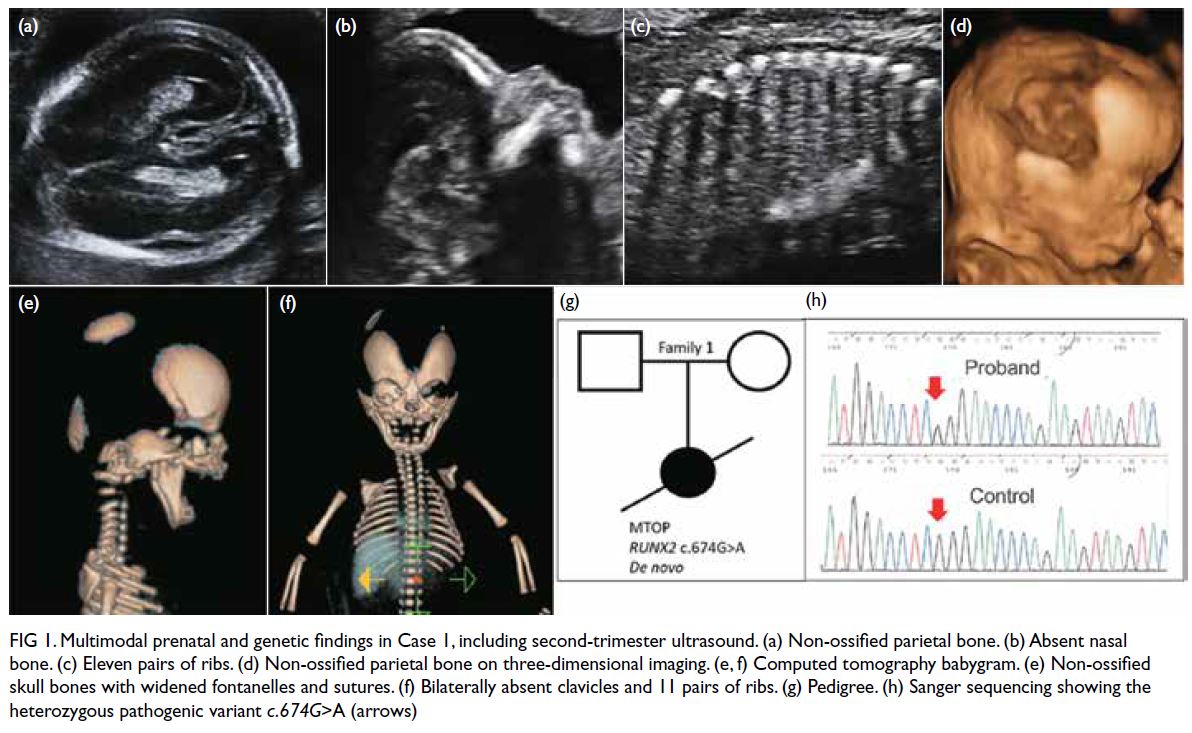

A primigravida attended our fetal medicine clinic

(FMC) in March 2015 at 12 weeks’ gestation for first-trimester

(T1) Down syndrome screening. Ultrasound

examination revealed an absent nasal bone (NB). A

morphology scan at 20 weeks confirmed this finding,

along with bilateral non-ossified parietal bones, 11

pairs of ribs, and shortened femur and humerus.

Amniocentesis revealed a normal chromosomal

microarray. The couple opted for termination of

pregnancy at 22 weeks. A computed tomography

babygram confirmed the ultrasound findings and

also showed bilaterally absent clavicles, hinting at a

diagnosis of cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD). Targeted

sequencing of the RUNX2 gene on the amniotic fluid

sample revealed a de novo heterozygous pathogenic

missense variant, c.674G>A (p.Arg225Gln),

confirming the diagnosis. Multimodal prenatal and

genetic findings were illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Multimodal prenatal and genetic findings in Case 1, including second-trimester ultrasound. (a) Non-ossified parietal bone. (b) Absent nasal bone. (c) Eleven pairs of ribs. (d) Non-ossified parietal bone on three-dimensional imaging. (e, f) Computed tomography babygram. (e) Non-ossified skull bones with widened fontanelles and sutures. (f) Bilaterally absent clavicles and 11 pairs of ribs. (g) Pedigree. (h) Sanger sequencing showing the heterozygous pathogenic variant c.674G>A (arrows)

Cases 2 and 3 (Family 2)

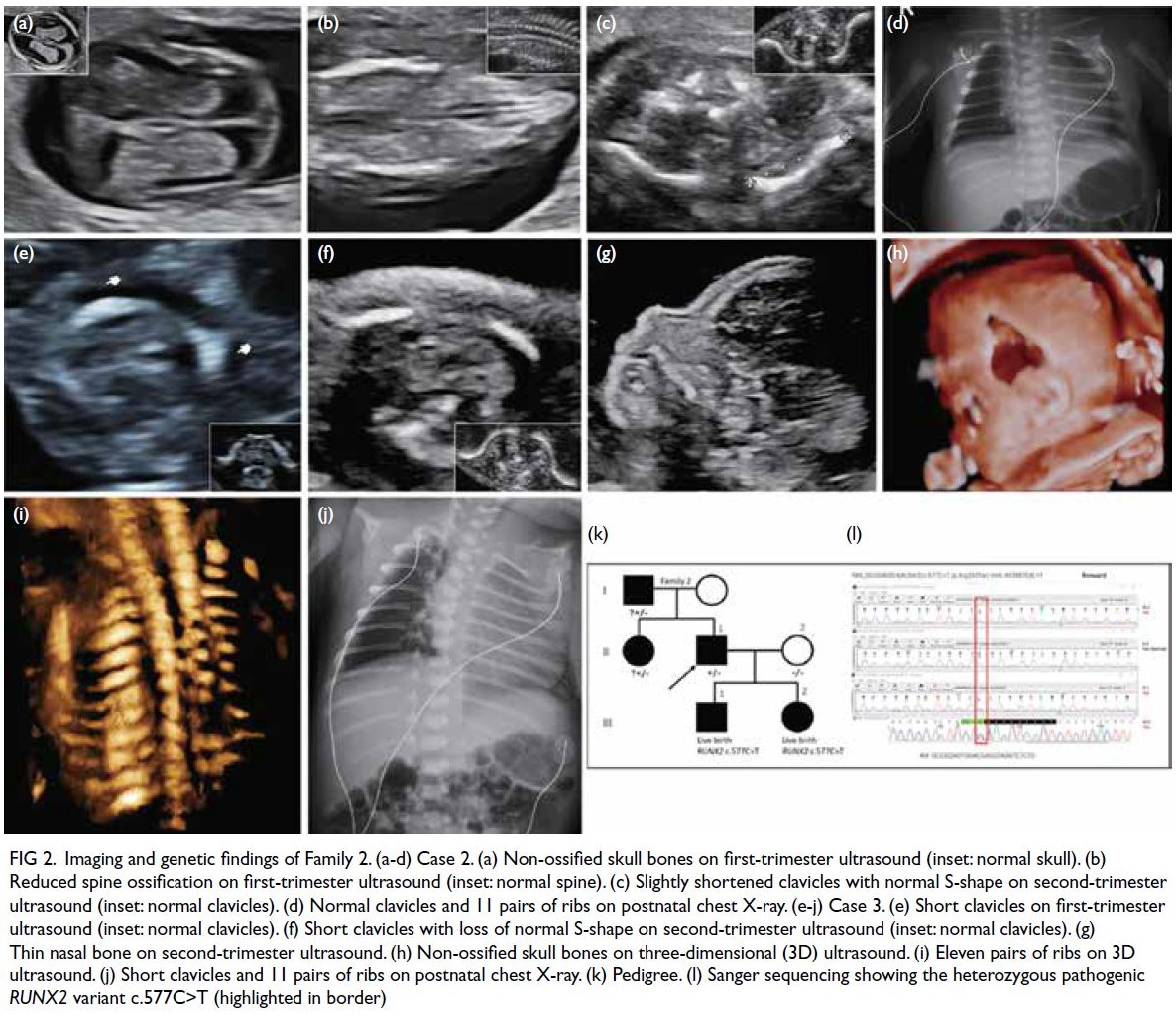

A primigravida attended the FMC in July 2022

at 12 weeks’ gestation for non-invasive prenatal

screening (NIPS) for fetal aneuploidy. Ultrasound

showed non-ossified skull bones (SB) and reduced

spine ossification, but both clavicles were present. A

review of the paternal history revealed that he had

features of CCD, including the ability to approximate

his shoulders, similar to a character in an American

drama with diagnosed CCD. Molecular testing for

CCD showed a pathogenic nonsense variant in the

RUNX2 gene, c.577C>T (p.Arg193Ter), confirming

the diagnosis. The fetus was thus suspected to have the

same genetic problem. The couple declined invasive

genetic testing. Instead, NIPS was performed using a

novel technique known as coordinative allele-aware target enrichment sequencing (COATE-seq). This

facilitated concomitant screening for chromosomal

and monogenic disorders, encompassing 10

aneuploidies, 12 microdeletions and 64 monogenic

disorders including RUNX2-related diseases (online supplementary Table 1). Results showed that the

fetus was at high risk of having a pathogenic variant

in the RUNX2 gene c.577C>T (p.Arg193Ter). Serial

ultrasound showed normal SB ossification but

with widened sutures, normal spine ossification,

and mildly shortened clavicles with a normal S

shape. A male infant was delivered at 39 weeks.

Skeletal survey showed a persistent metopic suture,

widened anterior fontanelle, 11 pairs of ribs, delayed

ossification of pubic bones with widely spaced public

symphysis, but both clavicles were present. Targeted

RUNX2 variant analysis on the cord blood sample

validated the presence of the paternal heterozygous

pathogenic variant.

In the same patient’s second pregnancy, she

attended the FMC at 12 weeks in January 2024 where

ultrasound showed hypoplastic clavicles, non-ossified

SBs and reduced spine ossification. The NIPS

using COATE-seq showed that the fetus was at high

risk of having the same pathogenic RUNX2 variant,

c.577C>T (p.Arg193Ter). The couple declined

invasive confirmatory testing. Serial ultrasound

showed non-ossified SBs with widened sutures

and fontanelle, a thin NB, very short clavicles with

loss of normal S shape, 11 pairs of ribs, and mildly

shortened long bones. A female infant was delivered

at 38 weeks. Skeletal survey revealed bilateral

hypoplastic clavicles and 11 pairs of ribs. Targeted

RUNX2 variant analysis of the cord blood sample

validated the presence of the paternal heterozygous

pathogenic variant, confirming the diagnosis.

Imaging and genetic findings are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Imaging and genetic findings of Family 2. (a-d) Case 2. (a) Non-ossified skull bones on first-trimester ultrasound (inset: normal skull). (b) Reduced spine ossification on first-trimester ultrasound (inset: normal spine). (c) Slightly shortened clavicles with normal S-shape on second-trimester ultrasound (inset: normal clavicles). (d) Normal clavicles and 11 pairs of ribs on postnatal chest X-ray. (e-j) Case 3. (e) Short clavicles on first-trimester ultrasound (inset: normal clavicles). (f) Short clavicles with loss of normal S-shape on second-trimester ultrasound (inset: normal clavicles). (g) Thin nasal bone on second-trimester ultrasound. (h) Non-ossified skull bones on three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound. (i) Eleven pairs of ribs on 3D ultrasound. (j) Short clavicles and 11 pairs of ribs on postnatal chest X-ray. (k) Pedigree. (l) Sanger sequencing showing the heterozygous pathogenic RUNX2 variant c.577C>T (highlighted in border)

Discussion

Cleidocranial dysplasia is a rare autosomal dominant

skeletal dysplasia characterised by the classic

triad of absent or hypoplastic clavicles, delayed

ossification of the cranial bones with delayed

closure of sutures and fontanelles, and dental

abnormalities.1 Approximately two-thirds of cases

are caused by RUNX2 gene mutations, with the

remaining one-third resulting from copy number

variations, translocations, or inversions involving

the RUNX2 locus.2 The RUNX2 gene, located

on chromosome 6p21, encodes a transcription

factor that regulates osteoblast differentiation and

chondrocyte maturation.3 Haploinsufficiency of

RUNX2 gene leads to delayed intramembranous and

endochondral ossification.3 The skull and clavicles,

formed by intramembranous ossification, are

therefore the most frequently affected.3

Prenatal diagnosis of CCD is rare. Including

our three cases, only 22 cases have been reported

to date (online supplementary Table 2). Most had

affected family members, hinting at the diagnosis.

Most were diagnosed based on clinical findings, with

only 10 cases having a molecular diagnosis of RUNX2

gene defects. This highlights the pivotal role of

prenatal ultrasound in identifying the characteristic features, namely, absent or hypoplastic clavicles,

absent or inadequate SB ossification with wide

fontanelles and sutures, and shortened long bones

and absent NB. Among these, clavicular defect is

the most characteristic. All three cases in our series

had these typical features, detected during the first

trimester, with an additional novel finding of 11

pairs of ribs. Nevertheless, the prenatal detection of

CCD can be difficult as ultrasound features may be

subtle. Although clavicles can be visualised during

T1 ultrasound, they are not routinely examined.

Conversely, absent NB, a marker for aneuploidy and

routinely assessed during T1 nuchal translucency

measurement, may be an important clue that

prompts further examination of the clavicles and

skull. With a positive family history, prenatal

detection of inherited CCD by ultrasound may be

more feasible. However, this can remain challenging

as pathogenic RUNX2 variants exhibit complete

penetrance but variable expressivity.1 Within the

same family, one affected fetus may present with a

subtle phenotype while another may show more

pronounced manifestations, as illustrated by the

two siblings in Family 2. Therefore, meticulous

ultrasound is imperative in pregnancies at risk of

CCD.

When CCD is suspected, invasive genetic testing

is usually recommended to confirm the diagnosis

through targeted RUNX2 variant analysis. However,

invasive testing is associated with 0.1% to 0.2% risk of

procedure-related fetal loss.4 As CCD rarely results

in severe disability, many parents, particularly

affected ones, may not consider termination of

pregnancy and may choose to avoid invasive testing.

In such cases, the new NIPS approach, COATE-seq,

provides a viable diagnostic alternative.5 Its

performance in high-risk pregnancies has been

validated, demonstrating 98.5% sensitivity and

99.3% specificity compared with standard diagnostic

methods.6 The two cases in Family 2 represent the

first report of prenatal detection of CCD through the

identification of a pathogenic RUNX2 variant using

this novel technique. These cases highlight the great potential of combining T1 ultrasound with NIPS for

early, non-invasive prenatal detection. This powerful

non-invasive approach may also be applicable to

other autosomal dominant skeletal dysplasia and

monogenic disorders.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KW Choy, YH Ting.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Y Cao, YH Ting.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Y Cao, YH Ting.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Y Cao, YH Ting.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Y Cao, YH Ting.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the affected families for participating in

and supporting this study.

Funding/support

This study was supported by the National Key Research

and Development Program of China (Grant No.:

2023YFC2705603). The funder had no role in study design,

data collection/analysis/interpretation or manuscript

preparation.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of

Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2017.442). Written

informed consent was obtained from the families for

publication of clinical details and images.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association. The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Machol K, Mendoza-Londono R, Lee B. Cleidocranial

dysplasia spectrum disorder. 3 Jan 2006 [updated 13 Apr

2023]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, editors.

GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington;

1993.

2. Motaei J, Salmaninejad A, Jamali E, et al. Molecular

genetics of cleidocranial dysplasia. Fetal Pediatr Pathol

2021;40:442-54. Crossref

3. Hassan NM, Dhillon A, Huang B. Cleidocranial dysplasia:

clinical overview and genetic considerations. Pediatr Dent

J 2016;26:45-50. Crossref

4. Akolekar R, Beta J, Picciarelli G, Ogilvie C, D’Antonio F.

Procedure-related risk of miscarriage following

amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2015;45:16-26. Crossref

5. Xu C, Li J, Chen S, et al. Genetic deconvolution of fetal and

maternal cell-free DNA in maternal plasma enables next-generation

non-invasive prenatal screening. Cell Discov

2022;8:109. Crossref

6. Zhang J, Wu Y, Chen S, et al. Prospective prenatal cell-free

DNA screening for genetic conditions of heterogenous

etiologies. Nat Med 2024;30:470-9. Crossref