Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:Epub 4 Dec 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

Expert consensus recommendations on the daily

clinical use of pembrolizumab for early triple-negative

breast cancer

Winnie Yeo, MD, FRCP1; Yolanda HY Chan, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Surgery)2; Roland CY Leung, MRCP, DABIM3; Sharon WW Chan, FRACS, FHKAM (Surgery)4; Lorraine CY Chow, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Surgery)5; William WL Foo, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)6; Sara WW Fung, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Surgery)7; Carol CH Kwok,FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)8; Stephanie HY Lau, FRCSEd, FHKAM (Surgery)9; Alex KC Leung, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)10; Ting Ying Ng, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)11; Janice Tsang, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)12,13; Iris KM Wong, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)14; Chun Chung Yau, FRCP, FHKAM (Radiology)15; Marvin HY Yuen, FRACS, FHKAM (Surgery)16; Polly SY Cheung, FRCS, FRACS17

1 Department of Clinical Oncology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Breast Health Clinic, CUHK Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Surgery, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Private Practice, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 Radiotherapy and Oncology Centre, Gleneagles Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

7 Department of Surgery, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

8 Department of Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

9 Department of Surgery, Hong Kong Baptist Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

10 Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

11 Department of Clinical Oncology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

12 Founding Convenor, Hong Kong Breast Oncology Group, Hong Kong SAR, China

13 School of Clinical Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

14 Department of Oncology, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

15 Comprehensive Oncology Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

16 Department of Surgery, Pok Oi Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

17 Breast Care Centre, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Winnie Yeo (winnie@clo.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a standard treatment for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) at an

early stage. Given that pathological complete

response is strongly associated with long-term

clinical and survival benefits, the selection of

appropriate treatment before and after surgery

could further optimise treatment outcomes. With

the emergence of immunotherapy in breast cancer,

more combination treatment options are available,

such as pembrolizumab, a programmed death

receptor 1 inhibitor, which is approved for the

perioperative treatment of stage II and III TNBC.

However, the implementation of immunotherapy

in perioperative settings for TNBC requires further

discussion regarding patient selection and the

use of different treatments in conjunction with

immunotherapy. The Hong Kong Breast Cancer

Foundation convened a multidisciplinary consensus

panel consisting of surgeons, clinical oncologists,

and medical oncologists to initiate this discussion.

A modified Delphi panel was conducted, evaluating

seven topics and 45 statements covering the workup

and perioperative treatment of early-stage TNBC

(eTNBC). The consensus statements provide

guidance on determining whether a patient with

eTNBC is a suitable candidate for neoadjuvant

chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), representing

10% to 15% of breast cancer cases, is characterised

by the absence of oestrogen receptors (ER),

progesterone receptors (PR), and human epidermal

growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) amplification

or overexpression. It is associated with higher

rates of recurrence, metastasis, and worse overall

survival (OS) than other subtypes.1 2 Given its high immune infiltration rate, with over 50% tumour-infiltrating

lymphocytes in histological samples,3 4

TNBC is amenable to immunomodulation through

immunotherapy.

Immunotherapies directed against

programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) or

programmed death receptor ligand 1 (PD-L1)

have shown promising and positive results in

patients with metastatic TNBC (mTNBC), based on the phase III randomised KEYNOTE-355

and IMpassion130 trials.5 6 7 Addition of the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab to chemotherapy

significantly improved progression-free survival and

OS by 4.1 months and 6.9 months, respectively, in

patients with mTNBC whose tumours expressed

PD-L1 (combined positive score [CPS] ≥10).5 6

The effectiveness of neoadjuvant

pembrolizumab in combination with neoadjuvant

chemotherapy (NAC) was demonstrated in the

KEYNOTE-5228 9 and NeoImmunoBoost trials.10

The pathological complete response (pCR) rate

significantly increased from 51.2% among patients

receiving NAC alone to 64.8% among those receiving

pembrolizumab–chemotherapy in the former study,

independent of PD-L1 status.8 Event-free survival

(EFS) at 36 months also increased from 76.8% to

84.5%.9 Although pembrolizumab demonstrated

favourable results in the KEYNOTE-522 study,

several important questions regarding patient

selection, types and schedules of chemotherapy,

and treatment plans for patients with residual

disease after surgery remain in real-world practice.

Therefore, the Hong Kong Breast Cancer Foundation

(HKBCF) convened a multidisciplinary consensus to

guide the practical use of pembrolizumab locally.

The results of this consensus were partially

presented during the Hong Kong Breast Cancer

Symposium in November 2023 and in abstract form

at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual

Meeting 2024.11 Here, we present the full results.

Methods

To explore the perioperative use of immunotherapy

and provide expert guidance for routine clinical practice in the treatment of early triple-negative

breast cancer (eTNBC), the HKBCF established

a consensus panel comprising seven breast

surgeons, six clinical oncologists, and three medical

oncologists, each with at least 15 years of clinical

experience.

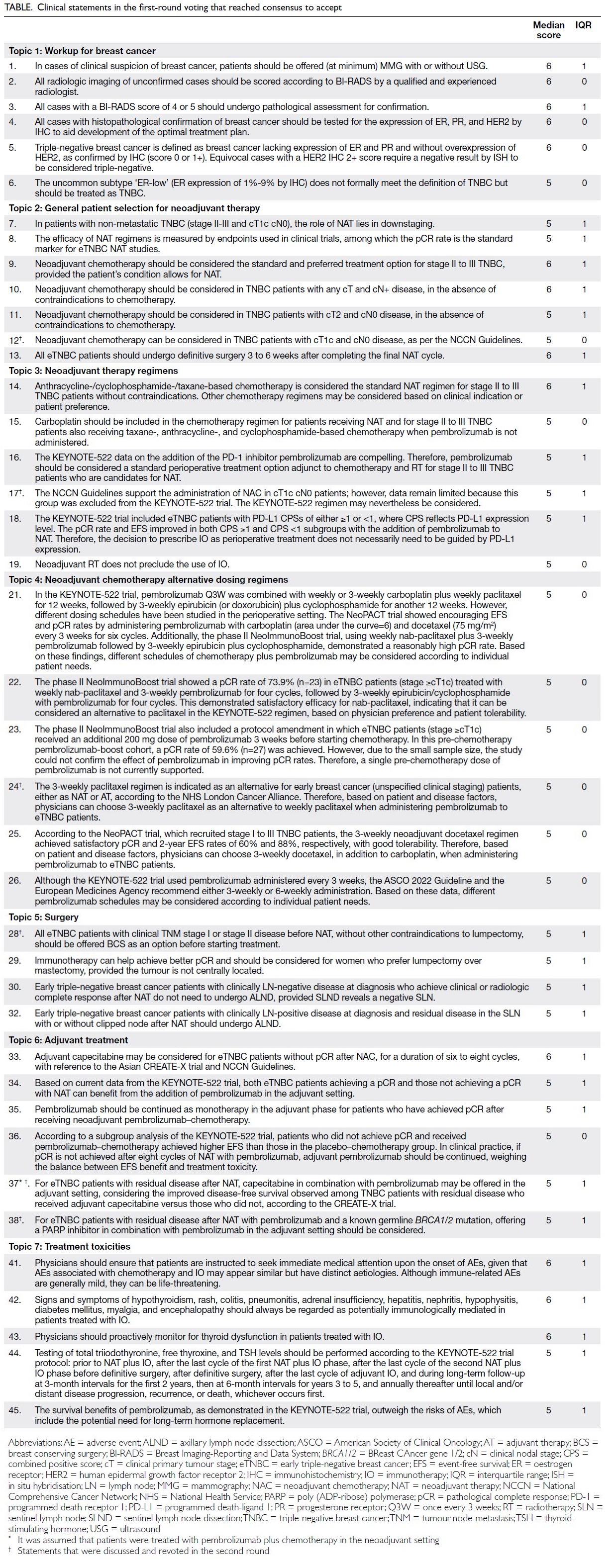

A modified Delphi panel was conducted on

seven topics encompassing 45 statements, covering

the workup for TNBC as well as neoadjuvant and

adjuvant treatment for eTNBC. Statements relating

to surgery were prepared by breast surgeons, whereas

statements concerning non-surgical interventions

were developed by oncologists. The statements were

generated with reference to established guidelines

and clinical trials, after a non-systematic search of

databases for literature published in English without

time restrictions. The levels of evidence and strength

of recommendations were determined using a two-level

grading system.12

In the first round, votes from 64 practising

healthcare professionals in Hong Kong—including

surgeons (n=21), clinical oncologists (n=36), and

medical oncologists (n=7)—were collected through

an online form using a six-point Likert scale:

Strongly disagree = 1; Disagree = 2; Slightly disagree

= 3; Slightly agree = 4; Agree = 5; Strongly agree = 6. No midpoint or neutral option was provided to

encourage definitive responses. Consensus to accept

(CTA) was defined as a median score ≥5 with an

interquartile range (IQR) ≤1.75. Consensus to reject

(CTR) was defined as a median score ≤2 with an

IQR ≤1.75. The results, including statements that

did not reach consensus, were discussed further by

16 senior panellists, who voted anonymously during

a consensus meeting. All panellists were invited to

review the manuscript contents to confirm the final

statements, as described in later sections. The first-and

second-round voting results are summarised in

the Table and online supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

All voting data were analysed using SPSS (Windows

version 28.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United

States) to determine consensus. Recommendations

were graded using the GRADE (Grading of

Recommendations Assessment, Development and

Evaluation) system as strong (grade 1) or weak

(grade 2); the quality of evidence was classified as

high (grade A), moderate (grade B), or low (grade

C).12 This manuscript follows the AGREE (Appraisal

of Guidelines Research and Evaluation) reporting

guideline.

Consensus statements

Workup for breast cancer

Respondents and panellists agreed that all women

with clinical suspicion of breast cancer should be

offered mammography, with or without ultrasound,

and that imaging should be scored according to the BI-RADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data

System) by a qualified and experienced radiologist.

The definition of TNBC was also highlighted,

referring to breast cancer that lacks expression of ER

and PR and does not exhibit overexpression of HER2.

Two key statements relating to the histopathology of

TNBC are presented below:

Statement 4: All cases with histopathological

confirmation of breast cancer should be tested for

the expression of oestrogen receptors, progesterone

receptors, and human epidermal growth factor

receptor 2 by immunohistochemistry to aid the

development of the optimal treatment plan. (CTA;

Recommendation: 1A)

Statement 6: The uncommon subtype ‘oestrogen

receptors–low’ (oestrogen receptor expression of

1%-9% by immunohistochemistry) does not formally

meet the definition of triple-negative breast cancer

but should be treated as triple-negative breast

cancer. (CTA; Recommendation: 2C)

It was agreed that assessment of ER/PR

expression and HER2 overexpression in breast

cancer is essential to facilitate treatment planning

and should be confirmed before treatment initiation.

The panel regarded ER-low–positive (1%-9% ER

expression) breast cancer as a biologically distinct

subgroup for which treatment consensus has not

yet been established, due to the uncertain benefit

of endocrine therapy.13 A prospective multicentre

registry study of 516 patients conducted between

2011 and 2019 showed that demographic and clinical

characteristics, as well as BRCA1/2 mutation status,

were comparable between ER-low breast cancer

and TNBC.14 The respondents therefore believed

that breast cancer exhibiting low ER expression on

immunohistochemistry should be treated as TNBC.

General patient selection for neoadjuvant

therapy

The importance of neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) for downstaging non–metastatic TNBC (non-mTNBC)

was generally agreed upon by respondents and

panellists. Patients with stage II to III disease or

node-negative cases with a primary tumour size

between 1 and 2 cm should be considered for NAT.

Definitive surgery should be performed within 3 to

6 weeks after completion of the final cycle of NAT.

Two key statements relating to NAC use for eTNBC

are discussed below:

Statement 9: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be

considered the standard and preferred treatment

option for stage II to III triple-negative breast

cancer, provided the patient’s condition allows for

neoadjuvant therapy. (CTA; Recommendation: 1A)

Statement 12: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be

considered in triple-negative breast cancer patients

with clinical tumour stage 1c (cT1c) and clinical

nodal stage 0 (cN0) disease, as per the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. (CTA;

Recommendation: 1C)

The St Gallen Consensus Conference

recommends adding carboplatin to neoadjuvant

paclitaxel, followed by anthracyclines and

cyclophosphamide, for stage II to III TNBC.15

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Guidelines state that preoperative systemic therapy

is preferred for TNBC patients at clinical stage ≥cT2

or ≥cN1 and can also be considered for cT1cN0.16

The American Society of Clinical Oncology

recommends offering an anthracycline- and taxane-containing

regimen in the neoadjuvant setting for

patients with TNBC at clinical stage cT1cN0M0,17

whereas the European Society for Medical Oncology

guidelines suggest NAT for TNBC patients with

cT1cN0 disease or greater.18 After reviewing these

guidelines, the panellists agreed on the use of NAT

for TNBC patients with a clinical tumour size of 1 to

2 cm and no palpable lymph nodes (LNs).

The panellists also noted that, in clinical

practice, establishing a multidisciplinary team

comprising surgeons and oncologists is essential

when developing a treatment plan, particularly for

patients who may be eligible for breast conserving

surgery (BCS) after NAT. Patient adherence to

treatment plans proposed by a multidisciplinary team

is reportedly higher, according to a retrospective

study conducted in Europe.19

Neoadjuvant therapy regimens

Anthracycline/cyclophosphamide/taxane-based

chemotherapy is the standard NAT regimen for

stage II to III TNBC.20 In addition to standard

chemotherapy, respondents and panellists agreed

that other regimens may be considered as clinically

indicated or according to patient preferences. The

addition of platinum agents and immune checkpoint

inhibitors should also be considered, given the

improved EFS observed in stage II or III TNBC

patients in recent clinical trials.9 21 Based on the

results of the KEYNOTE-522 trial, respondents and

panellists supported the addition of pembrolizumab

to NAT for TNBC, regardless of PD-L1 expression

level.8 9 Three key statements concerning the use of

pembrolizumab are highlighted below:

Statement 15: Carboplatin should be included in

the chemotherapy regimen for patients receiving

neoadjuvant therapy and for stage II to III triple-negative

breast cancer patients also receiving

taxane-, anthracycline-, and cyclophosphamide-based

chemotherapy when pembrolizumab is not

administered. (CTA; Recommendation: 1C)

Statement 16: The KEYNOTE-522 data on the

addition of the programmed death receptor

ligand 1 inhibitor pembrolizumab are compelling.

Therefore, pembrolizumab should be considered a

standard perioperative treatment option adjunct

to chemotherapy and radiotherapy for stage II

to III triple-negative breast cancer patients who

are candidates for neoadjuvant therapy. (CTA;

Recommendation: 1B)

Statement 17: The National Comprehensive Cancer

Network Guidelines support the administration

of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in clinical tumour

stage 1c (cT1c) and clinical nodal stage 0 (cN0)

patients; however, data remain limited because

this group was excluded from the KEYNOTE-522 trial. The KEYNOTE-522 regimen may

nevertheless be considered. (Neither CTA nor CTR;

Recommendation: 2C)

Respondents and panellists emphasised the

importance of adding carboplatin to backbone

chemotherapy in the NAT of TNBC. A meta-analysis

and systematic review of platinum-based NAT

across 11 randomised controlled trials involving

2946 patients suggested that platinum-based

chemotherapy was associated with a higher pCR rate

(40%) compared with platinum-free chemotherapy

(27%).22 Subgroup analysis showed that taxane plus

platinum chemotherapy increased the pCR rate

to 44.6% vs 27.8% for platinum-free treatment,

supporting the neoadjuvant use of carboplatin plus

taxane chemotherapy.22

The phase III KEYNOTE-522 trial

demonstrated that preoperative pembrolizumab plus

chemotherapy achieved a significantly higher pCR

rate (64.8% vs 51.2%; P<0.001) than chemotherapy

alone in untreated stage II to III TNBC patients.8

These promising findings were further supported by

the trial’s 60-month EFS rates, which were 81.3% and

72.3% in the pembrolizumab and control groups,

respectively.23

Patients with cT1a or cT1bN0 TNBC should

not be routinely offered NAT outside clinical trials;

guidelines suggest a case-by-case approach to

NAT for treating cT1cN0M0 disease.16 Although

combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors and

chemotherapy have been extensively studied in three

phase II and III neoadjuvant trials (KEYNOTE-522,8 IMpassion031,24 and NeoImmunoBoost10),

none included cT1cN0 patients. Thus, the panel

concluded that there is insufficient evidence to

justify extrapolating the addition of immunotherapy

to chemotherapy for this patient group.

Panellists were divided on the use of immune

checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab,

in all cT1N0 disease. Some noted that evidence

from phase III studies is currently limited, whereas

others supported the use of pembrolizumab in cT1N0 disease given its inclusion in the NeoPACT

trial.25 Nonetheless, individualised discussions and

multidisciplinary team consultations are encouraged

for each case before treatment.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy alternative

dosing regimens

Dosing schedules may influence treatment

response, safety outcomes, and patient compliance.

Respondents and panellists were open to various

dosing regimens combining pembrolizumab with

platinum and taxane, followed by anthracyclines.6 10 25

Dose-dense anthracycline was not considered

an alternative to the 3-weekly schedule when

neoadjuvant pembrolizumab is administered.

Two key statements on 3-weekly and weekly

dosage schedules are highlighted below for further

discussion:

Statement 24: The 3-weekly paclitaxel regimen

is indicated as an alternative for early breast

cancer (unspecified clinical staging) patients,

either as neoadjuvant therapy or adjuvant therapy,

according to the National Health Service London

Cancer Alliance. Therefore, based on patient and

disease factors, physicians can choose 3-weekly

paclitaxel as an alternative to weekly paclitaxel

when administering pembrolizumab to early triple-negative

breast cancer patients. (Neither CTA nor

CTR; Recommendation: 2B)

Statement 25: According to the NeoPACT trial,

which recruited stage I to III triple-negative breast

cancer patients, the 3-weekly neoadjuvant docetaxel

regimen achieved satisfactory pathological complete

response and 2-year event-free survival rates of

60% and 88%, respectively, with good tolerability.

Therefore, based on patient and disease factors,

physicians can choose 3-weekly docetaxel, in

addition to carboplatin, when administering

pembrolizumab to early triple-negative breast

cancer patients. (CTA; Recommendation: 2C)

The National Health Service London Cancer

Alliance recommends administering paclitaxel once

every 3 weeks (Q3W) for four cycles in early breast

cancer.26 However, the E1199 trial investigated

the optimal dosing of docetaxel or paclitaxel after

anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide in 4954

patients with axillary LN-positive or high-risk

LN-negative breast cancer, including 1025 TNBC

patients.27 Although no difference was observed in

the primary comparisons of taxane type (docetaxel

vs paclitaxel) or schedule (3-weekly vs weekly), a

secondary analysis with a 10-year update reported

that weekly paclitaxel produced more favourable

survival outcomes than the 3-weekly schedule. In

TNBC patients, higher 10-year disease-free survival

(DFS) and OS were noted with weekly paclitaxel (Q1W) compared with Q3W (69% vs 58.7%; hazard

ratio [HR]=0.69; P=0.01 and 75.1% vs 65.6%; HR=0.69;

P=0.019, respectively), supporting the adjuvant

use of weekly paclitaxel.27 In the recent phase II

NeoPACT trial, the neoadjuvant combination of

pembrolizumab, carboplatin, and docetaxel Q3W

achieved a pCR rate of 58% (95% confidence interval

[95% CI]=48%-67%) and a 3-year EFS of 86% for all

patients.25 If validated in a phase III randomised

study, this combination may represent a future 3-weekly anthracycline-free chemoimmunotherapy

option for TNBC patients.25

The efficacy of paclitaxel Q3W remains

controversial. Although consensus was not reached,

all panellists participating in the discussion preferred

weekly paclitaxel (Q1W), considering its long-term

data on efficacy, tolerability, and toxicity, as well as

its consistency with the KEYNOTE-522 regimen,

which utilises weekly paclitaxel in combination with

pembrolizumab.8 9 The panellists did not consider

paclitaxel Q3W to be an optimal alternative to

weekly regimens but agreed that 3-weekly taxane

(docetaxel or paclitaxel) regimens may provide a

practical treatment schedule for selected patients.

Surgery

Respondents and panellists agreed that the addition

of immunotherapy to chemotherapy improves pCR

rates in patients who wish to undergo BCS after

NAT. For patients with clinically negative LNs at

diagnosis who achieve a complete response after

NAT, extensive axillary surgery may be omitted

if sentinel LN dissection reveals negative nodes.

However, the panellists did not support applying

the same approach to patients who had clinically

positive LNs at diagnosis.

One statement concerning the option of

offering BCS before the initiation of treatment was

discussed:

Statement 28: All early triple-negative breast cancer

patients with clinical tumour-node-metastasis stage

I or stage II disease before neoadjuvant therapy,

without other contraindications to lumpectomy,

should be offered breast conserving surgery as an

option before starting treatment. (Neither CTA nor

CTR; Recommendation: 1C)

According to the National Comprehensive

Cancer Network Guidelines,16 early-stage

(≤cT1cN0) operable breast cancer patients may

undergo upfront BCS or mastectomy with adjuvant

systemic therapy where indicated, whereas patients

with clinical stage ≥cT2 or ≥cN disease should be

treated with NAT. The European Society for Medical

Oncology guidelines state that BCS is the preferred

local treatment option for most early breast cancer

patients, but aggressive phenotypes such as eTNBC

should receive NAT first28; BCS should only be offered when the response to NAT is satisfactory.28

The 17th St Gallen International Guidelines also

recommend dose-dense anthracycline- and taxane-based

NAT for stage II or III eTNBC but do not

comment on stage I disease.29

The panellists declined to endorse the

statement, noting that NAT is a treatment option

for eTNBC patients but not a prerequisite for BCS

in stage I or II disease. However, it is noteworthy

that in-breast recurrences represent 5% to 15% of

all recurrence events in early-stage breast cancer

under contemporary BCS and RT management.30 31

Recurrence rates have continued to improve with

advances in therapy. In a recent meta-analysis of

14 studies involving 19 819 TNBC patients who

underwent BCS (plus radiotherapy) or mastectomy,

the pooled odds ratio for locoregional recurrence

was 0.64 (95% CI=0.48-0.85; P=0.002), the pooled

odds ratio for distant metastasis was 0.70 (95%

CI=0.53-0.94; P=0.02), and the pooled HR for

all-cause mortality was 0.78 (95% CI=0.69-0.89;

P<0.001) among patients who underwent BCS

relative to mastectomy.32 Another retrospective

study of 12 761 patients with T1-2N0M0 TNBC

also revealed significantly higher 5-year OS (89% vs

84.5%; P<0.001) and breast cancer–specific survival

(93% vs 91%; P<0.001) in patients receiving BCS

and radiotherapy compared with those undergoing

mastectomy alone.33 Both meta-analyses did not

report outcome differences between adjuvant

therapy with upfront BCS and NAT followed by

BCS in eTNBC. Given these encouraging data, the

panellists regarded the statement as unclear but

raised no objection to recommending upfront BCS

for selected patients with ≤cT1cN0 eTNBC. Risk

factors, including age, tumour grade, and disease

stage, should be considered when offering this

treatment option.

Adjuvant treatment

For patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant

pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy, adding

capecitabine to adjuvant pembrolizumab was

considered acceptable. However, consensus

was not reached among panellists regarding the

combined use of a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

inhibitor and pembrolizumab in the adjuvant setting

for patients with residual disease and a known

germline BRCA1/2 mutation (gBRCA1/2m), due to

variations in local testing practices for gBRCA1/2m.

Discussions of scenarios that may benefit from the

adjuvant use of pembrolizumab are summarised in

the two statements below:

Statement 34: Based on current data from the

KEYNOTE-522 trial, both early triple-negative

breast cancer patients achieving a pathological

complete response and those not achieving a pathological complete response with neoadjuvant

therapy can benefit from the addition of

pembrolizumab in the adjuvant setting. (CTA; Recommendation: 1B)

Statement 37: For early triple-negative breast cancer

patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant

therapy, capecitabine in combination with

pembrolizumab may be offered in the adjuvant

setting, considering the improved disease-free

survival observed among triple-negative breast

cancer patients with residual disease who received

adjuvant capecitabine versus those who did

not, according to the CREATE-X trial. (CTA; Recommendation: 2B)

According to the KEYNOTE-522 trial, patients

receiving perioperative pembrolizumab and NAC

demonstrated better EFS than those treated with

NAC alone (84.5% vs 76.8%, HR=0.63; 95% CI=0.48-0.82) at a median follow-up of 39.1 months.9 Further

EFS analysis based on pCR outcomes showed that

patients who did not achieve pCR also benefited

from the KEYNOTE-522 regimen (67.4% vs 56.8%,

HR=0.7; 95% CI=0.52-0.95).9 The panellists agreed

that for patients who did not achieve pCR after

neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy,

adjuvant pembrolizumab—or pembrolizumab

combined with capecitabine—should be

administered.

Based on the CREATE-X (Capecitabine for

Residual Cancer as Adjuvant Therapy)34 and EA1131

trials,35 patients without a pCR after NAT may

benefit from adjuvant capecitabine. The phase III

CREATE-X study enrolled 910 HER2-negative breast

cancer patients with residual disease after NAT

containing anthracycline, taxane, or both. Those

who received standard treatment with capecitabine

demonstrated better long-term survival outcomes

than the control (capecitabine-free) group. Among

286 patients with residual TNBC, those receiving

adjuvant capecitabine achieved higher DFS (69.8%

vs 56.1%; HR=0.58; 95% CI=0.39-0.87) and OS

(78.8% vs 70.3%; HR=0.52; 95% CI=0.30-0.90) than

those in the control group at 5 years.34 Another

phase III EA1131 study of 410 patients with residual

TNBC after NAT also showed better 3-year invasive

DFS among those receiving adjuvant capecitabine

(49.4%; 95% CI=39.0%-59.0%) than among those

receiving adjuvant platinum (42.0%; 95% CI=30.5%-53.1%), although the difference was not statistically

significant.35

Despite the lack of mature data regarding

the adjuvant use of capecitabine in combination

with pembrolizumab, the KEYNOTE-522 study

demonstrated the additional benefit of perioperative

pembrolizumab with NAC without increasing

chemotherapy-related adverse effects in the

neoadjuvant setting.8 9 The panellists considered that adding capecitabine to pembrolizumab in patients

without pCR after NAT plus pembrolizumab

represents a clinically feasible option to improve

long-term survival outcomes in cases where residual

disease is observed after pembrolizumab-based NAT.

They noted that the combination of pembrolizumab

and capecitabine has been reported to be safe and

tolerable in mTNBC.36 However, further prospective

studies are required to determine the long-term

survival and safety benefits, as well as the optimal

dosing schedule, in eTNBC. The panellists ultimately

reached a consensus to accept this statement, adding

that adjuvant capecitabine with pembrolizumab may

be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Treatment toxicities

Respondents and panellists reached consensus on all

statements relating to treatment toxicities without

requiring further discussion in the second round.

In summary, for patients receiving immunotherapy

plus chemotherapy, clinicians should monitor for

potential immunotherapy-related adverse events,

which are generally mild in most patients but

may be life-threatening in some cases. Thyroid

function should be proactively monitored, given

that reversible destructive thyroiditis and overt

hypothyroidism commonly occur in patients

receiving pembrolizumab.37

Conclusion

The development of these consensus statements

on the management of eTNBC involved a

multidisciplinary panel of oncologists and breast

surgeons from public, private, and academic

institutions, providing a comprehensive overview

of clinical practice in Hong Kong. These statements

offer guidance to clinicians regarding the general

work-up, treatment, and use of immunotherapy for

TNBC patients who do not fit the patient profile

enrolled in the KEYNOTE-522 study.

Author contributions

Concept or design: PSY Cheung, W Yeo.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PSY Cheung, W Yeo.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PSY Cheung, W Yeo, YHY Chan, RCY Leung.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PSY Cheung, W Yeo.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PSY Cheung, W Yeo, YHY Chan, RCY Leung.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

CC Yau received speaker’s honoraria from Novartis and

Eli Lilly. AKC Leung is the Second Vice President of the

Hong Kong Breast Oncology Group. All other authors have

disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge and thank all breast surgeons,

clinical oncologists, and medical oncologists in Hong Kong

who supported this consensus by voting during the first round

of the Delphi methodology.

Declaration

The consensus statement results were presented at The

Chinese University of Hong Kong Breast Cancer Meeting

(28-29 October 2023, Hong Kong) and as a poster presentation

at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting

2024 (31 May to 4 June 2024, Chicago, United States).

Funding/support

The study was funded by the Hong Kong Breast Cancer

Foundation Limited with the support of Merck Sharp and

Dohme (Asia) Limited. Medical writing support was provided

by MediPaper Medical Communications Limited. The funders

had no role in the study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Ahn SG, Kim SJ, Kim C, Jeong J. Molecular classification of

triple-negative breast cancer. J Breast Cancer 2016;19:223-30. Crossref

2. Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, et al. Triple-negative

breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence.

Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:4429-34. Crossref

3. Solinas C, Carbognin L, De Silva P, Criscitiello C,

Lambertini M. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast

cancer according to tumor subtype: current state of the art.

Breast 2017;35:142-50. Crossref

4. Stanton SE, Adams S, Disis ML. Variation in the incidence

and magnitude of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in

breast cancer subtypes: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol

2016;2:1354-60. Crossref

5. Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, et al. Pembrolizumab

plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy

for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or

metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355):

a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3

clinical trial. Lancet 2020;396:1817-28. Crossref

6. Cortes J, Rugo HS, Cescon DW, et al. Pembrolizumab plus

chemotherapy in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N

Engl J Med 2022;387:217-26. Crossref

7. Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel

in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2108-21. Crossref

8. Schmid P, Cortes J, Pusztai L, et al. Pembrolizumab for early

triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382:810-21. Crossref

9. Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al. Event-free survival with

pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N

Engl J Med 2022;386:556-67. Crossref

10. Fasching PA, Hein A, Kolberg HC, et al. Pembrolizumab

in combination with nab-paclitaxel for the treatment of

patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer—a

single-arm phase II trial (NeoImmunoboost, AGO-B-041).

Eur J Cancer 2023;184:1-9. Crossref

11. Yeo W, Chan YH, Leung RC, et al. Expert consensus

recommendations on the daily clinical use of

pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer

[abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2024;42(Suppl 16):e12521. Crossref

12. Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading

strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in

clinical guidelines: report from an American College of

Chest Physicians task force. Chest 2006;129:174-81. Crossref

13. Malainou CP, Stachika N, Damianou AK, et al. Estrogen-receptor-low–positive breast cancer: pathological and clinical perspectives. Curr Oncol 2023;30:9734-45. Crossref

14. Yoder R, Kimler BF, Staley JM, et al. Impact of low versus

negative estrogen/progesterone receptor status on clinico-pathologic

characteristics and survival outcomes in HER2-negative breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022;8:80. Crossref

15. Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, Gnant M, et al. Understanding

breast cancer complexity to improve patient outcomes:

The St Gallen International Consensus Conference for the

Primary Therapy of Individuals with Early Breast Cancer

2023. Ann Oncol 2023;34:970-86. Crossref

16. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN

Guidelines. Breast Cancer. Available from: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. Accessed 2 Sep 2023. Crossref

17. Korde LA, Somerfield MR, Carey LA, et al. Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted therapy for

breast cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:1485-505. Crossref

18. Loibl S, André F, Bachelot T, et al. Early breast cancer:

ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment

and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2024;35:159-82. Crossref

19. Fancellu A, Pasqualitto V, Cottu P, et al. The importance of

the multidisciplinary team in the decision-making process

of patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for

breast cancer. Updates Surg 2024;76:1919-26. Crossref

20. von Minckwitz G, Martin M. Neoadjuvant treatments for

triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Ann Oncol 2012;23

Suppl 6:vi35-9. Crossref

21. Geyer CE, Sikov WM, Huober J, et al. Long-term efficacy

and safety of addition of carboplatin with or without

veliparib to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in

triple-negative breast cancer: 4-year follow-up data from

BrighTNess, a randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol

2022;33:384-94. Crossref

22. Pandy JG, Balolong-Garcia JC, Cruz-Ordinario MV, Que FV.

Triple negative breast cancer and platinum-based systemic

treatment: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC

Cancer 2019;19:1065. Crossref

23. Schmid P, Cortés J, Dent RA, et al. LBA18 Pembrolizumab

or placebo plus chemotherapy followed by pembrolizumab

or placebo for early-stage TNBC: updated EFS results from the phase III KEYNOTE-522 study [abstract]. Ann Oncol

2023;34 Suppl:S1257. Crossref

24. Mittendorf EA, Zhang H, Barrios CH, et al. Neoadjuvant

atezolizumab in combination with sequential nab-paclitaxel

and anthracycline-based chemotherapy versus placebo and

chemotherapy in patients with early-stage triple-negative

breast cancer (IMpassion031): a randomised, double-blind,

phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;396:1090-100. Crossref

25. Sharma P, Stecklein SR, Yoder R, et al. Clinical and

biomarker findings of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab and

carboplatin plus docetaxel in triple-negative breast cancer:

NeoPACT phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2024;10:227-35. Crossref

26. London Cancer Alliance. LCA Breast Cancer Clinical

Guidelines. Oct 2013. Available from: https://www.transformationpartners.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/LCA-Breast-Cancer-Clinical-Guidelines.pdf. Accessed 5 Nov 2025.

27. Sparano JA, Zhao F, Martino S, Ligibel JA, et al. Long-term

follow-up of the E1199 phase III trial evaluating the role of

taxane and schedule in operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol

2015;33:2353-60. Crossref

28. Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. Early breast

cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis,

treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1194-220. Crossref

29. Burstein HJ, Curigliano G, Thürlimann B, et al. Customizing

local and systemic therapies for women with early breast

cancer: the St. Gallen International Consensus Guidelines

for treatment of early breast cancer 2021. Ann Oncol

2021;32:1216-35. Crossref

30. Sestak I, Cuzick J, Bonanni B, et al. Abstract GS2-02:

12-year results of anastrozole versus tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer in postmenopausal women

with locally excised ductal carcinoma in-situ [abstract].

Cancer Res 2021;81 Suppl 4:GS2-02. Crossref

31. Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up

of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy,

lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for

the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med

2002;347:1233-41. Crossref

32. Fancellu A, Houssami N, Sanna V, Porcu A, Ninniri C,

Marinovich ML. Outcomes after breast-conserving

surgery or mastectomy in patients with triple-negative

breast cancer: meta-analysis. Br J Surg 2021;108:760-8. Crossref

33. Saifi O, Chahrour MA, Li Z, et al. Is breast conservation

superior to mastectomy in early stage triple negative breast

cancer? Breast 2022;62:144-51. Crossref

34. Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine

for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N Engl

J Med 2017;376:2147-59. Crossref

35. Mayer IA, Zhao F, Arteaga CL, et al. Randomized phase III

postoperative trial of platinum-based chemotherapy versus

capecitabine in patients with residual triple-negative breast

cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy: ECOG-ACRIN

EA1131. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2539-51. Crossref

36. Page DB, Pucilowska J, Chun B, et al. A phase Ib trial of

pembrolizumab plus paclitaxel or flat-dose capecitabine in

1st/2nd line metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. NPJ

Breast Cancer 2023;9:53. Crossref

37. Delivanis DA, Gustafson MP, Bornschlegl S, et al.

Pembrolizumab-induced thyroiditis: comprehensive

clinical review and insights into underlying involved

mechanisms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:2770-80. Crossref