Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 9 Dec 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Improving efficiency and effectiveness of workplace-based assessment workshop in postgraduate medical education using a conjoint design

HY So, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology), MHPE1; Eddy WY Wong, FHKCORL, FRCSEd (ORL)2; Albert KM Chan, FHKCA, MHPE1; George KC Wong, MD, FCSHK1; Jessica YP Law, FHKCOG, MHQS (Harvard)3; PT Chan, FHKCOS, MMEd1; CM Ngai, FHKCORL, FRCS (Edin)2

1 The Jockey Club Institute for Medical Education and Development, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 The Hong Kong College of Otorhinolaryngologists, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr HY So (sohingyu@fellow.hkam.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Faculty development for trainers and

nurturing feedback literacy in trainees is crucial for

effective workplace-based assessments (WBAs) to

support trainee competency development. Separate

training sessions for trainers and trainees can be

challenging when resources are limited. Combined

training can optimise resources and foster mutual

understanding, although such approaches face

challenges related to power dynamics. This study

aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a conjoint

WBA workshop in enhancing trainer engagement,

improving trainee feedback literacy, and exploring

the benefits and challenges of integrating trainers

and trainees in a shared learning environment.

Methods: A mixed-methods study was conducted

with 13 trainers and five trainees from the Hong Kong

College of Otorhinolaryngologists. Quantitative

data were collected using the Feedback Literacy

Behaviour Scale for trainees and the Continuing

Professional Development–Reaction Questionnaire

for trainers. Pre- and post-intervention comparisons

were analysed using paired t tests. Qualitative data

from focus group interviews were thematically

analysed.

Results: Quantitative analysis showed statistically

significant increases in trainee feedback literacy

(P<0.001) and improvements in trainers’ beliefs

about capabilities and engagement intentions

(P<0.05). The qualitative analysis supported these findings and identified three key factors: mutual

understanding, clarification of the WBA purpose,

and effective instructional design. Participants

valued the mutual understanding fostered in the

conjoint setting, which aligned expectations and

created a supportive learning environment.

Conclusion: Conjoint WBA workshops may

effectively promote trainer engagement and trainee

feedback literacy, aligning expectations and fostering

a positive feedback culture. Further research is

needed to explore the longitudinal impact and

applicability to other specialties.

New knowledge added by this study

- Trainers and trainees learning together in the same workplace-based assessment (WBA) workshop facilitates effective mutual learning.

- Despite potential power dynamics, psychological safety can be maintained in this setting.

- Collaboration strengthens trainees’ trust in the value of WBA as a tool for learning.

- Conjoint training can be considered an alternative for organising WBA workshops.

- The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine should support further studies on this design to enhance the effectiveness of WBA workshops.

Introduction

Competency-based medical education (CBME)

emphasises the assessment of trainees through direct

observation and feedback using workplace-based

assessments (WBA).1 These assessments are designed to support continuous learning and competency

development through meaningful feedback.2 Effective

implementation of WBA requires trainers who are

willing and able to provide constructive feedback,3 4 5

and trainees who are motivated to seek and use feedback. This active engagement with feedback is

the essence of feedback literacy, defined by Carless

and Boud6 as “the understandings, capacities, and

dispositions needed to make sense of information

and use it to enhance work or learning strategies”.

The construct of intention, based on the theory of

planned behaviour, highlights that an individual’s

willingness to perform a behaviour is influenced

by their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived

behavioural control.7 Intention is emphasised as

the best predictor of behaviour, especially where

constraints or barriers exist. In the context of WBA,

focusing on intention helps us understand the

underlying motivations and readiness of trainers and

trainees to engage in feedback practices. Trainers’

intentions are shaped by their beliefs about the value

of feedback, the expectations of peers, and their

confidence in their ability to provide that feedback.

Dawson et al,8 building on the works of Carless and

Boud6 and Molloy et al,9 conceptualised feedback

literacy as five key skills: seeking feedback, making

sense of information, using feedback, managing

emotional responses, and providing feedback. Based

on this framework, effective training is essential for

fostering engagement and capability in meaningful

feedback practices.

Faculty development is often implemented to

enhance trainers’ skills, whereas separate sessions aim to build feedback literacy among trainees.

However, specialties with small numbers of trainers

and trainees face unique challenges in implementing

WBA, including limited opportunities to conduct

separate training sessions. A conjoint WBA

workshop, where both groups train together, may offer

an innovative solution to these constraints. Potential

benefits include promoting mutual understanding,

aligning feedback practices, and fostering a

consistent approach to WBA implementation.10

However, concerns regarding power imbalances and

psychological safety in mixed-group settings could

undermine its effectiveness.11 Thus far, there have

been no studies regarding such conjoint workshops;

the actual participant experience, including potential

advantages and disadvantages, remains unexplored.

Therefore, this study aimed to address the following research questions:

- Can conjoint training improve the intention of trainers to participate in WBA?

- Can conjoint training improve the feedback literacy of trainees?

- What are the experiences of trainers in a conjoint training setting?

- What are the experiences of trainees in a conjoint training setting?

Methods

This study was designed according to the requirements

of the SQUIRE-EDU (Standards for QUality

Improvement Reporting Excellence in Education)

guidelines for educational improvement.12

Study setting

The study was conducted with trainers and trainees

of the Hong Kong College of Otorhinolaryngologists

(HKCORL), a specialty college under the Hong

Kong Academy of Medicine. The HKCORL is

responsible for training and accrediting specialists in

otorhinolaryngology, and has been integrating WBAs

into its training curriculum since 2021. The College

currently has a total of 206 fellows, 57 of whom

are trainers. In May 2023, 20 trainers participated

in a WBA workshop specifically designed for

them. During the first 2 years, basic surgical

trainees are under the Hong Kong Intercollegiate

Board of Surgical Colleges and rotate through

different surgical specialties. Specialist training in

otorhinolaryngology takes place only during the 4

years of higher training. Over the past 5 years, the

annual intake of higher trainees has ranged from

four to 11. Currently, there are 31 higher trainees,

26 of whom participated in a WBA workshop for

trainees held in September 2023. Relationships

among fellows and trainees are strengthened

through regular training courses, academic lectures,

workshops, and an annual scientific meeting, complemented by active participation from the

Young Fellows Chapter to enhance engagement

in College activities. Camaraderie is also fostered

through sports activities and social events.

Participant sampling and recruitment

All participants in the workshop were invited by

email to participate in this study on a voluntary

basis. All 13 trainers and five trainees enrolled in

the workshop volunteered to participate in the

study. The cohort of trainers was relatively young; 11

were within 10 years of obtaining their fellowship,

and seven had only 1 to 2 years of experience as

specialists.

Instructional design

The 4-hour workshop was designed based on the

first principles of instruction, emphasising task-centred

learning as the core instructional approach.13

Participants engaged in two authentic learning

tasks: procedural-based assessment and case-based

discussion, each followed by guided reflection. These

tasks provided opportunities to practise giving and

receiving feedback, which was the main focus of the

workshop.

To prepare for these tasks, participants first

completed a pre-course e-learning module consisting

of five interactive videos (total duration: 53 minutes).

These videos introduced essential concepts,

including CBME, self-regulated learning, feedback

literacy, and the procedures of WBA. The workshop

began with an activity to establish psychological

safety, following the recommendations of Rudolph

et al,14 ensuring that participants felt comfortable to

learn and engage openly. Subsequently, participants’

knowledge was reactivated through interactive

lectures and demonstrations, effectively preparing

them for the practice activities.

Quantitative measures

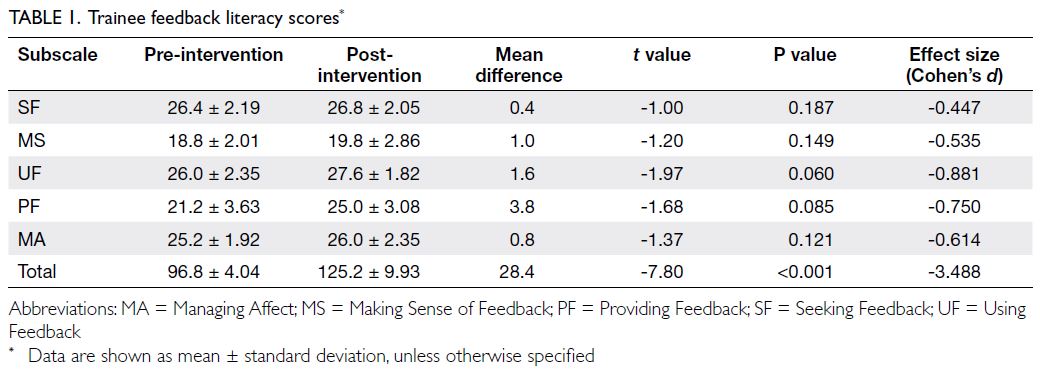

- Trainee feedback literacy: The Feedback Literacy Behaviour Scale was used to assess changes in trainees’ feedback literacy. It measures five subscales: Seeking Feedback, Making Sense of Feedback, Using Feedback, Providing Feedback, and Managing Affect.8

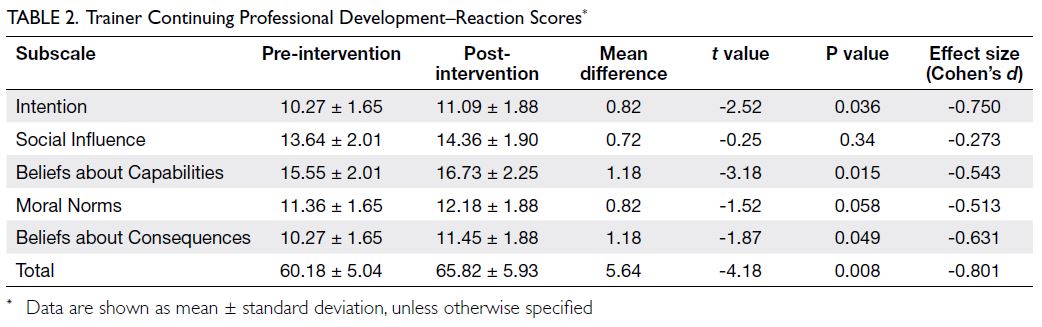

- Trainer engagement in WBA: Trainers’ engagement was measured using the Continuing Professional Development (CPD)–Reaction Questionnaire, based on social cognitive theories (theory of planned behaviour and Triandis’ theory of interpersonal behaviour). It measures intention, social influence, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, and moral norms.7 15 16

Both surveys were administered before

participants began their e-learning and repeated after completion of the workshop.

Statistical analysis

Paired t tests were utilised to compare pre- and post-intervention

scores for both groups because this

method offers more precise estimates of the effect

and improved control over confounding variables

compared with an unpaired t test, particularly

given the small sample size. Descriptive statistics,

including means, standard deviations, and Cohen’s d

effect sizes, were calculated for each measure using

Jamovi (desktop version 2.3.28).17

Qualitative data collection and analysis

Separate focus group interviews were conducted

for trainers and trainees immediately after the

workshop, using Cantonese. The two moderators

were research staff trained by the authors. Semi-structured

interviews were conducted using an

interview guide created by the authors (online

Appendix). The interviews were audio-recorded,

anonymised, and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts

were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s thematic

analysis approach,18 assisted by ATLAS.ti software

(version 8.4.5; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software

Development, Berlin, Germany).19

Member checking

To enhance the credibility of the qualitative findings,

results were sent back to participants after thematic

analysis to confirm whether they agreed with the

interpretation and whether they wished to share

additional views. This process helped strengthen the

credibility of the qualitative findings.

Reflexivity

The first author, an intensivist and educationist with

a Master’s degree in Health Professions Education,

played a key role in designing the conjoint workshop

and framing WBA as a learning tool. The second

author, a consultant otorhinolaryngologist and

CBME advocate, proposed the joint training

concept to address challenges in organising

separate trainer and trainee sessions. Support

from the seventh author, president of HKCORL,

was critical for workshop implementation. Other

authors contributed diverse clinical and educational

expertise: the third author, a consultant anaesthetist

and faculty development chair of the Jockey Club

Institute for Medical Education and Development

of the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine; the fifth

author, an obstetrics and gynaecology consultant

with expertise in healthcare quality and simulation;

the sixth author, an orthopaedic surgeon and former

college censor; and the fourth author, a neurosurgeon

experienced in WBA workshops.

Their collective advocacy for CBME and WBA

informed the study design and interpretation. While

offering rich, multifaceted insights into WBA, this

commitment may have influenced the emphasis on

the conjoint workshop’s benefits, shaping research

questions and conclusions accordingly.

Results

Quantitative findings

Among the trainees, the total Feedback Literacy

Score significantly increased (pre=96.8 ± 4.04,

post=125.2 ± 9.93; P<0.001), associated with a large

effect size (d= –3.488). There was no statistically

significant difference in the subscales of the Feedback

Literacy Score (Table 1).

Among the trainers, the CPD–Reaction Scores

showed statistically significant improvement in

intention (pre=10.27 ± 1.65, post=11.09 ± 1.88;

P=0.036), beliefs about capabilities (pre=15.55 ±

2.01, post=16.73 ± 2.25; P=0.015), beliefs about

consequences (pre=10.27 ± 1.65, post=11.45 ± 1.88; P=0.049), and total score (pre=60.18 ± 5.04,

post=65.82 ± 5.93; P=0.008). The effect sizes

were moderate to large for intention (d= –0.750),

moderate for beliefs about capabilities (d= –0.543)

and beliefs about consequences (d= –0.631), and

large for the total score (d= –0.801) [Table 2].

Qualitative findings

Trainee focus group analysis

Four themes were identified: understanding WBA

assessment, enhancing feedback literacy, presence

of trainers in the workshop, and workshop design

and delivery. Subthemes and quotations under each

theme are listed in online supplementary Table 1.

Trainer focus group analysis

Four themes were identified: perceptions of WBA, improvement in feedback skills, presence of trainees

in the workshop, and workshop design and delivery.

Subthemes and quotations under each theme are

listed in online supplementary Table 2.

Discussion

This mixed-methods study evaluated the impact of a

conjoint WBA workshop designed to enhance both

trainer intention to participate in WBA and trainee

feedback literacy. The quantitative and qualitative

data converged to show that the conjoint workshop

improved trainer intention and appreciation of

feedback skills; it also enhanced trainee feedback

literacy and confidence in managing feedback during

their learning process. Specifically, the quantitative

results showed statistically significant improvement in trainer intention to participate in WBA as measured

by the CPD–Reaction Questionnaire, and in trainee

feedback literacy as measured by the Feedback

Literacy Behaviour Score. Moreover, the qualitative

findings suggested that trainers appreciated the use

of open-ended questions and integration of feedback

into micro-moments as valuable strategies, whereas

trainees reported increased confidence in managing

feedback and constructively applying it to their

learning processes.

Through analysis of the qualitative data, we

also identified three key factors that contributed

to these findings: mutual understanding between

trainers and trainees, clarification of the purpose of

WBA, and effective instructional design.

Mutual understanding between trainers and

trainees

A key finding of this study was the positive reception

of the mixed-group learning experience. Both

trainers and trainees valued the opportunity to

directly engage with each other, which fostered

mutual understanding of the assessment process

and reduced discrepancies in feedback practices.

Notably, the absence of prominent power dynamics

was striking. This may be partially attributed to

the relatively young cohort of trainers, which likely

fostered a more collaborative atmosphere. Although

previous literature suggests that hierarchical

structures can hinder open communication in

feedback settings,11 the present study demonstrated

that in contexts with flatter hierarchies, conjoint

workshops can be highly effective. Trainees

indicated that the emphasis on psychological

safety during the workshop helped prepare them

for meaningful participation. Adherence to the

recommendations of Rudolph et al14 to establish a

safe environment likely contributed to this positive

outcome. The close relationships already present

between trainers and trainees within this small

specialty could also have contributed. Existing

literature supports the importance of trainer–trainee

relationships in WBA.4 20 Interactions within this

psychologically safe environment facilitated a more

unified understanding of assessment standards and

expectations, which helped minimise discrepancies

in feedback practices. This alignment fostered trust

that both trainers and trainees were working towards

the shared goal of using WBA for learning purposes.

Our qualitative findings indicated that both

groups reported a highly positive experience. The

distinction lay in the focus: trainees emphasised

gains in feedback literacy and confidence, whereas

trainers valued new practical strategies and

enhanced mutual understanding. According to the

conceptual model of Castanelli et al,21 the level of

trust in supervisors influences trainees’ perceptions

of WBA. When trust is low, WBAs are regarded as performance evaluations, leading trainees to

adopt risk-minimising strategies.22 Conversely,

when trust is high, trainees perceive WBA as an

assessment for learning, making them more willing

to embrace vulnerability. Our findings suggest that,

with appropriate measures to ensure psychological

safety, a combined workshop setting may help align

expectations, create a shared understanding of WBA

practices, and strengthen trainees’ trust in their

trainers.

Clarification of the purpose of

workplace-based assessment

Both trainers and trainees recognised that WBA

serves as a formative tool that guides reflective

practice and enhances clinical competence. This

understanding is crucial because it aligns with

the principles of adult learning, particularly the

notion that adults are self-directed learners who

take responsibility for their own education.23 When

both trainers and trainees appreciate that WBA

facilitates reflective practice, they engage in self-directed

learning by utilising feedback to critically

analyse their clinical performance. This process

empowers them to identify areas for improvement

and take actionable steps towards enhancing their

skills. Moreover, adults are motivated to learn when

the material is directly relevant to their professional

needs.23 In this context, WBA’s role in guiding clinical

competence is highly pertinent because it connects

seamlessly with daily practice. Thus, WBA not only

fosters a culture of continuous improvement but

also effectively motivates adult learners by linking

assessment to professional development. However,

motivation alone is insufficient. Participants also

noted barriers such as time constraints in the

clinical setting and the need for effective evaluation

of outcomes. These issues must be addressed to

ensure that motivation remains long-lasting and

that trainees continue to meaningfully engage with

WBAs in their everyday practice.

Effective instructional design

The workshop was designed based on the first

principles of instruction, an evidence-based model

that emphasises moving beyond memorisation to

active knowledge application through real-world

tasks.13 24 This approach encourages learners to

engage in practice, which is often challenging and

requires specific support. To address this, support is

twofold: cognitive and affective. Cognitive support

helps learners understand key concepts through pre-course

e-learning, reactivation of prior knowledge,

demonstration, and facilitated reflection.13 Affective

support focuses on ensuring psychological safety,

which is crucial for effective engagement in practice.14

While overall improvement reflects the combined effect of e-learning and the workshop, the qualitative

data indicate that the interactive, conjoint nature

of the workshop itself was the primary catalyst for

enhancing mutual understanding and feedback

skills. Our analysis revealed that participants valued

this design and highlighted two additional elements

that supported their learning: cognitive aids and

peer feedback.

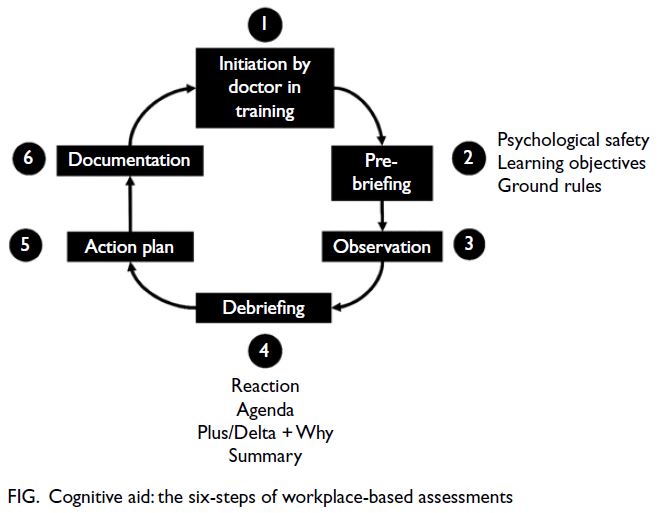

During the course, we used cognitive aids to

remind participants of this six-step framework (Fig),

and they found the use of such a framework effective.

Workplace-based assessments consist of recurrent

constituent skills—the steps to follow—and non-recurrent

constituent skills (eg, how to respond in

the debriefing conversation). The use of a structured

framework and just-in-time information, such as

cognitive aids, has been shown to effectively support

the learning of recurrent skills.25

During the guided reflection, we also engaged

participants in peer feedback. Our analysis showed

that participants found this practice enhanced their

learning. Peer feedback enhances metacognitive

perceptions by encouraging learners to reflect on

their understanding and performance in relation to

their peers. This fosters self-awareness as learners

evaluate their work against others’, facilitating deeper

insights into strengths and areas for improvement.26

There is evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of

peer feedback in enhancing feedback literacy.27 28

Nonetheless, participants noted that the

workshop could be improved by providing clearer

instructions for role-playing exercises and using more

medical-related cases for demonstration. Effective

instruction is important. According to cognitive load

theory, ineffective guidance can increase extrinsic

cognitive load and impair learning, especially when the task itself is already demanding.29 We used a

movie-based scenario not related to medicine to

make the activity fun and interesting. However, the

participants’ comment is valid, considering evidence

that similarity between demonstration and practice is

crucial for effective learning. When demonstrations

closely resemble real-life applications, learners

can better understand and apply concepts. This

alignment enhances procedural knowledge, enabling

learners to transition from observation to imitation

and, eventually, autonomous practice. Furthermore,

relevant demonstrations foster engagement and allow

immediate feedback, which reinforces learning.30 31

Future workshops should focus on improving these

aspects for better learning outcomes.

Limitations and future directions

This study had some limitations. The quantitative

findings are constrained by the small sample

size, particularly among trainees (n=5), which

limits statistical power. Furthermore, although

participation in the workshop was encouraged by

the College, the sample may still reflect a group

more engaged in training initiatives, potentially

affecting generalisability. While the qualitative

data provided rich insights into participants’

experiences, a larger cohort could offer a broader

understanding of the impact of this educational

intervention. Additionally, the study did not assess

long-term changes in behaviour or practice, which

are needed to determine sustained effects of the

conjoint training on WBA implementation. Future

studies could explore the longitudinal impact of

such workshops and investigate their applicability in

larger specialties where power dynamics might differ.

It would also be valuable to assess the scalability of

conjoint workshops in different contexts, particularly

those with more complex hierarchical structures,

to better understand their potential for broader

implementation.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that conjoint WBA

workshops for trainers and trainees may effectively

enhance trainee feedback literacy and trainer

engagement in CBME. The mixed-group learning

experience promoted mutual understanding

and aligned feedback practices without creating

significant power imbalances, fostering positive

trainer–trainee interactions and enhancing trust,

provided measures are taken to ensure psychological

safety. Despite the positive outcomes, the study’s

limitations, including its small sample size and lack

of long-term follow-up, should be considered. Future

research could explore the longitudinal impact of

conjoint workshops and their applicability in larger

specialties with more complex power dynamics.

Author contributions

Concept or design: HY So, EWY Wong.

Acquisition of data: HY So, CM Ngai.

Analysis or interpretation of data: HY So, AKM Chan, GKC Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: HY So.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: HY So, CM Ngai.

Analysis or interpretation of data: HY So, AKM Chan, GKC Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: HY So.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Mr CF Chan and Ms Cathy Ma of the

Jockey Club Institute for Medical Education and Development

of Hong Kong Academy of Medicine for valuable assistance

in moderating the focus group discussions and preparing

the transcripts. The authors also appreciate the logistical

support provided by Ms Cindy Leung of The Hong Kong

College of Otorhinolaryngologists, as well as Mr CF Chan, Ms

Cathy Ma, and Ms Jojo Lee of the Jockey Club Institute for

Medical Education and Development of Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine in organising the workshop. Additionally, the

authors wish to express their heartfelt thanks to Professor Jack

Pun from the Department of English at The Chinese University

of Hong Kong and Professor Stanley Sau-ching Wong from

the Department of Anaesthesiology at The University of Hong

Kong for insightful contributions to the preparation of the

manuscript.

Declaration

Findings from this study were presented at AMEE 2025 of the

International Association for Health Professions Education,

23-27 August 2025, Barcelona, Spain.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Survey and Behavioural

Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong

Kong, Hong Kong (Ref No.: SBRE-23-0855). Information

sheets regarding the study were provided to all participants,

and signed consent was obtained from each participant prior

to the study

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. So HY, Choi YF, Chan PT, Chan AK, Ng GW, Wong GK.

Workplace-based assessments: what, why, and how to

implement? Hong Kong Med J 2024;30:250-4. Crossref

2. Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, Swing SR, Frank JR.

The role of assessment in competency-based medical

education. Med Teach 2010;32:676-82. Crossref

3. Anderson HL, Kurtz J, West DC. Implementation and

use of workplace-based assessment in clinical learning

environments: a scoping review. Acad Med 2021;96:S164-74. Crossref

4. Massie J, Ali JM. Workplace-based assessment: a

review of user perceptions and strategies to address the

identified shortcomings. Adv Heal Sci Educ Theory Pract

2016;21:455-73. Crossref

5. Lörwald AC, Lahner FM, Mooser B, et al. Influences on the

implementation of Mini-CEX and DOPS for postgraduate

medical trainees’ learning: a grounded theory study. Med

Teach 2019;41:448-56. Crossref

6. Carless D, Boud D. The development of student feedback

literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess & Eval High

Educ 2018;43:1315-25. Crossref

7. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ Behav

Hum Decis Processes 1991;50:179-211. Crossref

8. Dawson P, Yan Z, Lipnevich A, Tai J, Boud D, Mahoney P.

Measuring what learners do in feedback: the Feedback

Literacy Behaviour Scale. Assess Eval High Educ

2023;49:348-62. Crossref

9. Molloy E, Boud D, Henderson M. Developing a learning-centred

framework for feedback literacy. Assess Eval High

Educ 2020;45:527-40. Crossref

10. Illingworth P, Chelvanayagam S. Benefits of

interprofessional education in health care. Br J Nurs

2007;16:121-4. Crossref

11. Brooks AK. Power and the production of knowledge:

collective team learning in work organizations. Hum

Resour Dev Q 1994;5:213-35. Crossref

12. Ogrinc G, Armstrong GE, Dolansky MA, Singh MK,

Davies L. SQUIRE-EDU (Standards for QUality

Improvement Reporting Excellence in Education):

publication guidelines for educational improvement. Acad

Med 2019;94:1461-70. Crossref

13. Merrill MD. First principles of instruction. In: Reigeluth CM,

Carr-Chellman AA, editors. Instructional Design Theories

and Models: Building a Common Knowledge Base. Vol III.

New York: Routledge Publishers; 2009: 43-59.

14. Ruldolph JW, Raemer DB, Simon R. Establishing a safe

container for learning in simulation: the role of the

presimulation briefing. Simul Healthc 2014;9:339-49. Crossref

15. Légaré F, Borduas F, Freitas A, et al. Development of a

simple 12-item theory-based instrument to assess the

impact of continuing professional development on clinical

behavioral intentions. PLoS One 2014;9:e91013. Crossref

16. Triandis HC. Values, attitudes, and interpersonal behaviour.

In: Howe HE Jr, Page MM, editors. Nebraska Symposium

on Motivation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press;

1979: 195-259.

17. Jamovi Project. Jamovi (desktop version 2.3.28 for Mac).

2024. Available from: https://dev.jamovi.org. Accessed 25 Oct 2024.

18. Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. In Teo T, editor.

Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology. New York: Springer;

2014: 1947-52. Crossref

19. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH.

ATLAS.ti (software version 8.4.5). 2024. Available from: https://atlasti.com. Accessed 25 Oct 2024.

20. Baboolal SO, Singaram VS. Specialist training: workplace-based

assessments impact on teaching, learning and

feedback to support competency-based postgraduate

programs. BMC Med Educ 2023;23:941. Crossref

21. Castanelli DJ, Weller JM, Molloy E, Bearman M. Trust,

power and learning in workplace-based assessment: the

trainee perspective. Med Educ 2022;56:280-91. Crossref

22. Gaunt A, Patel A, Rusius V, Royle TJ, Markham DH,

Pawlikowska T. ‘Playing the game’: how do surgical trainees

seek feedback using workplace-based assessment? Med

Educ 2017;51:953-62. Crossref

23. Knowles MS, Holton EF III, Swanson RA. The Adult

Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and

Human Resource Development, 6th ed. Amsterdam:

Elsevier; 2005.

24. Francom GM, Gardner J. What is task-centered learning?

TechTrends 2014;58:27-35. Crossref

25. van Merriënboer JJ, Kirschner PA. Ten Steps to Complex

Learning: A Systematic Approach to Four-Component

Instructional Design. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge

Publisher; 2018. Crossref

26. Lerchenfeldt S, Kamel-ElSayed S, Patino G, Loftus S,

Thomas DM. A qualitative analysis on the effectiveness

of peer feedback in team-based learning. Med Sci Educ

2023;33:893-902. Crossref

27. Man D, Kong B, Chau MH. Developing student feedback

literacy through peer review training. RELC J 2024;55:408-21. Crossref

28. Little T, Dawson P, Boud D, Tai J. Can students’ feedback

literacy be improved? A scoping review of interventions.

Assess Eval High Educ 2023;49:39-52. Crossref

29. van Merriënboer JJ, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory in

health professional education: design principles and

strategies. Med Educ 2010;44:85-93. Crossref

30. McLain M. Developing perspectives on ‘the demonstration’

as a signature pedagogy in design and technology

education. Int J Tech Design Educ 2021;31:3-26. Crossref

31. Grossman R, Salas E, Pavlas D, Rosen MA. Using

instructional features to enhance demonstration-based

training in management education. Acad Manag Learn

Educ 2012;12:219-43. Crossref