Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 4 Feb 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PERSPECTIVE

Diagnostic challenges and treatment outcomes of

primary vitreoretinal lymphoma in Hong Kong

Arnold SH Chee, AFCOphthHK1,2,3; Andrew CY Mak, FCOphthHK1,2,3; KW Kam, FCOphthHK1,2,3; Molly SC Li, FHKCP4; Mary Ho, FCOphthHK1,2,3; Marten E Brelen, PhD1,2; LJ Chen, PhD1,2,3; Wilson WK Yip, FCOphthHK1,2,3; Alvin L Young, FRCSI1,2,3

1 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Clinical Oncology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Alvin L Young (youngla@ha.org.hk)

Introduction

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL) is a rare

and aggressive ocular variant of non-Hodgkin

lymphoma (NHL), predominantly of B-cell origin.1

It represents a subset of primary central nervous

system lymphoma (PCNSL), in which malignant

lymphocytic cells primarily affect the vitreous and/or retina, with or without involvement of the brain

and cerebrospinal fluid. Approximately one-fifth

of patients with PCNSL have concurrent ocular

manifestations at presentation, whereas 60% to

90% of patients with PVRL develop central nervous

system (CNS) disease within 16 to 24 months.2

The prognosis for patients with PVRL and

CNS involvement is poor, with a median survival

of 1 to 2 years.3 Thus, early diagnosis is imperative

for timely treatment. However, diagnosis is often

delayed because: (1) PVRL frequently masquerades

as chronic uveitis4; (2) the diagnostic yield of

vitreous samples is often low due to hypocellularity

and fragility of lymphoma cells3; (3) specialised

techniques and experienced cytopathologists are

required; and (4) patients often have reservations

about undergoing invasive diagnostic vitrectomy.

The current first-line treatment for PCNSL

comprises high-dose methotrexate (MTX)–based

polychemotherapy, with or without whole-brain

radiotherapy. Among patients with isolated PVRL,

intravitreal MTX has been shown to achieve ocular

tumour control in multiple studies.4 5 6 However,

there remains no consensus regarding the optimal

treatment regimen.

In Hong Kong, NHL is among the top ten

cancers in terms of both incidence (2.9%) and

mortality (2.6%).7 Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

(DLBCL) is the most common type of NHL globally

and locally.8 Given that more than 95% of PVRL

cases are DLBCL,9 it is important to examine the

treatment outcomes of this under-reported disease

entity.

Our local experience

We share our experience managing patients

diagnosed with PVRL at Prince of Wales Hospital

and Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Hong

Kong, between August 2013 and April 2024.

A case of PVRL was defined by the presence

of characteristic vitreous opacity and/or subretinal

infiltrate, substantiated by a positive tissue biopsy

from the vitreous, brain, or cerebrospinal fluid.

In cases without CNS involvement and negative

vitreous biopsy, the diagnosis was made by

consensus between two vitreoretinal specialists

based on clinical examination. Cases of systemic

NHL (eg, secondary vitreoretinal metastasis from

primary extracranial lymphoma) were excluded.

Visual acuity (VA), ocular examination findings,

and multimodal ocular imaging of the tumours were

recorded. Patient demographics, ocular symptoms,

follow-up duration, oncological treatment details,

complications, and survival data were collected.

Outcomes of interest included initial and final

VA and treatment responses. For the latter, an

international standardised guideline on ocular

responses in PCNSL was utilised10: (1) complete

response (absence of vitreous cells and resolution of

retinal infiltrate [online supplementary Fig a to b of

Patient 2 as reference]); (2) partial response (reduced

but persistent vitreous cells or retinal infiltrate);

(3) progressive disease (increased vitreous cells or

progressive retinal infiltrate); and (4) relapse (new

lesion in patients who had achieved a complete

response).

With ethics approval and waiver of patient

consent (The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics

Committee, Hong Kong [Ref No.: 2024.175]), 17 eyes

from 10 Chinese patients with PVRL were identified,

with a median follow-up of 32.5 months (range,

4-86). The majority of patients were women (70%)

and the median age at diagnosis was 59 years (range, 52-80; mean, 61.7). Three patients had isolated

ocular involvement, and seven had concurrent CNS

involvement. Among the latter, ocular involvement

preceded CNS disease in four patients (57.1%);

CNS involvement preceded ocular disease in three

patients (42.9%). The median interval between ocular

and CNS involvement was 13 months (range, 4-39).

Seven patients had bilateral PVRL, and all affected

eyes were symptomatic. Blurred vision was the most

common presenting complaint (90%), followed

by floaters (30%). The mean VA at presentation

was 20/100. The most common ophthalmological

finding was vitreous opacity, present in all eyes

(100%), followed by subretinal infiltrate in eight

eyes (47.1%) and secondary neovascular glaucoma

with vitreous haemorrhage in one eye (5.9%) [online

supplementary Table 1].

Diagnostic challenges of primary

vitreoretinal lymphoma

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma presents ongoing

diagnostic challenges. Its rarity and tendency

to masquerade as other ocular conditions can

delay diagnosis for up to 21 months.3 11 Accurate

cytopathological diagnosis is further hampered by

the intrinsically low volume of vitreous, fragility of

lymphoma cells, and hypocellularity.3 In our series,

all 10 patients (14 of 17 eyes) underwent diagnostic

and therapeutic vitrectomy (online supplementary

Table 2). Among the seven patients with suspicious

brain lesions on magnetic resonance imaging, brain

biopsy confirmed DLBCL and the diagnosis of PVRL

was supported by characteristic vitreous opacity

and/or subretinal infiltrate. For the remaining three

patients without CNS involvement, diagnosis relied

on positive vitreous biopsy findings: (1) cytology

demonstrating atypical lymphoid cells; (2) flow

cytometry identifying CD20+ B lymphocytes;

and (3) polymerase chain reaction revealing

monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy locus (IGH)

gene rearrangement. Two patients fulfilled these

criteria; Patient 10 was diagnosed solely based on

clinical evaluation by vitreoretinal specialists (online

supplementary Fig c to f). Only seven specimens

(50%) yielded positive cytological results with

malignant cells and/or atypical lymphoid cells (online

supplementary Table 2). Negative or equivocal

results do not definitively exclude lymphoma,9 thus

adjunctive cytopathological tests are often required.

These include, in decreasing order of sensitivity (as

ranked by a recent systematic review)3: interleukin

(IL) analysis (IL-10–to–IL-6 ratio >1; 89.4%), flow

cytometry identifying CD20+ B lymphocytes (88.0%),

monoclonal IGH rearrangement via polymerase

chain reaction (85.1%), and myeloid differentiation

primary response 88 (MYD88) mutation analysis

(70%). In our study, flow cytometry was performed

in six eyes (42.8%), with only two (14.2%) showing clonal populations. Polymerase chain reaction

was conducted in two eyes (14.3%); one (7.1%)

demonstrated IGH gene rearrangement. Interleukin

analysis was not performed. Flow cytometry and

gene rearrangement testing are available in the Hong

Kong public healthcare setting; other tests may incur

additional charges.12 A large Chinese case-control

study proposed a six-item diagnostic framework for

DLBCL-associated PVRL9 (online supplementary

Table 3). They reported that 15% of patients were

diagnosed when only criteria 1 to 3 were met.

Requiring criterion 1 plus two positive results from

criteria 4 to 6 increased diagnostic sensitivity to

97.5%, with 100% specificity.9

Several factors may have contributed to

the low diagnostic yield of vitreous biopsy in our

series. First, all patients received corticosteroids

to control ocular inflammation, given that PVRL

frequently masquerades as uveitis. This may

have induced cytolytic effects on lymphoma cells

prior to diagnostic vitrectomy.13 Second, vitreous

biopsy was not repeated in cases with equivocal or

negative cytological results, owing to the absence

of clinically significant vitreous opacities to justify

repeat sampling.3 Third, additional cytopathological

tests require prior arrangement and coordination

with on-duty cytopathologists. Sensitive assays,

such as IL analysis, could have been performed if

preliminary communication had occurred before

the vitreous biopsy. Finally, despite standardisation

of sampling techniques and procedures, sample

hypocellularity limited the yield of clonal lymphoma

cells on flow cytometry (2 of 6 eyes), where definitive

diagnosis requires a substantial number of viable,

intact neoplastic cells.3 To overcome the challenge of

hypocellular vitreoretinal lymphoma tissue samples,

the use of cell-free DNA, rather than cellular DNA, to

detect MYD88 mutations has been proposed. Notably,

detection rates were reportedly 30% higher when

cell-free DNA was used,14 even in aqueous humour

samples, which contain minimal cellular DNA. A

recent report has further validated this technique in

highly diluted (>100-fold) vitreous samples.15

Efficacy and safety of intravitreal

methotrexate in primary vitreoretinal

lymphoma

Before the introduction of intravitreal chemotherapy,

external beam radiation therapy was the primary

treatment for PVRL. Due to its severe adverse

effects, radiation therapy is now generally reserved

for patients with bilateral involvement, advanced

age, or difficulty attending frequent intravitreal

injections.1 Intravitreal MTX is currently considered

the first-line treatment owing to its high efficacy.1

To date, no standardised treatment regimen

for intravitreal MTX in PVRL has been established—the number of injections required to achieve a complete response varies widely.1 While Smith et al16

proposed a protocol of 25 injections, a 10-year

experience reported by Frenkel et al17 indicated

that only 39% of patients were able to complete

the treatment due to frailty or death. Notably, a

median of five injections (range, 2-11) was sufficient

to achieve a complete response. The same group

later reported a complete response rate of 97%

over a mean (± standard deviation) follow-up of

38 months with as few as five (± four) injections,4

which subsequently prompted proposals advocating

for fewer injections.6 16 In our study, intravitreal

MTX was administered at a dose of 400 μg/0.05

mL weekly. The number of injections was titrated

based on clinical response, defined as achievement

of complete response, and patient acceptance and

tolerance. Ultimately, nine eyes (52.9%) received

MTX injections, while eight eyes (47.1%) underwent

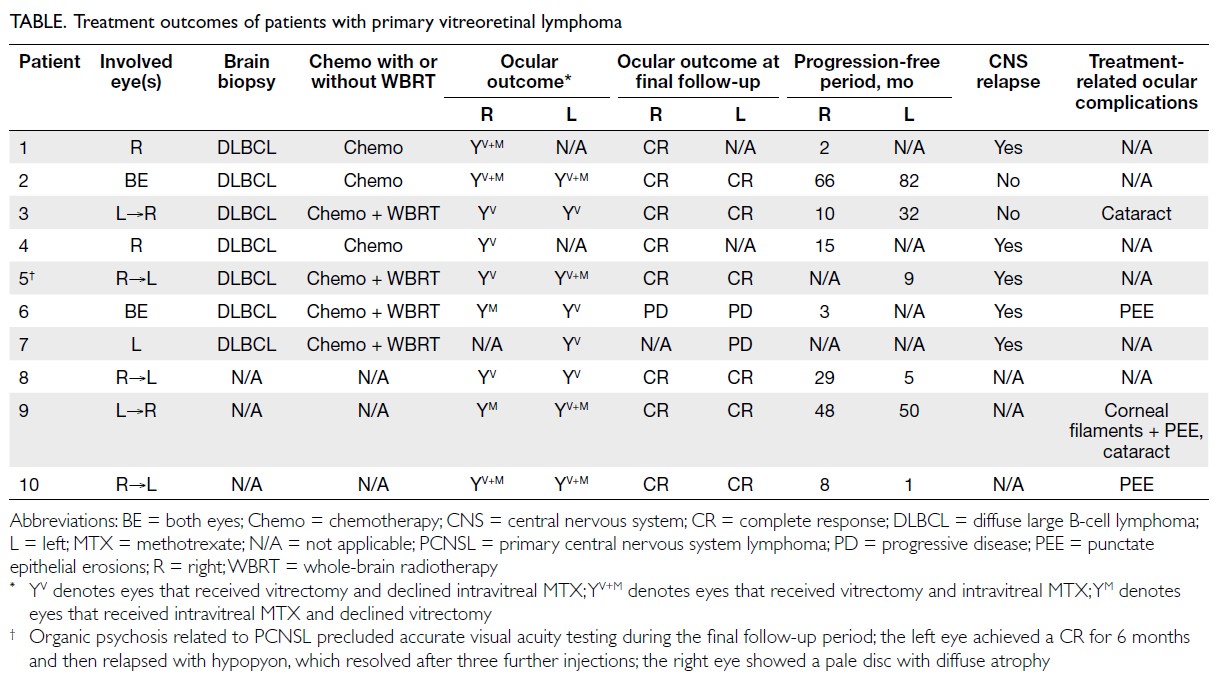

vitrectomy alone (Table). Methotrexate was not

administered in cases where patients achieved a

complete response after vitrectomy and declined

invasive treatment, experienced intolerance (Patient

6 developed keratopathy in the fellow treated eye), or

refused treatment for personal reasons (Patient 7).

Among MTX-treated eyes, a complete response

was achieved in seven eyes (77.8%), of which six had

stable vision and one experienced visual improvement

after a mean (± standard deviation) of five (± three)

injections (online supplementary Table 4). This

outcome is comparable to a series from the United

States (n=10), which reported a complete response rate of 80% and visual stability or improvement in

50% of cases following a mean of six MTX injections

(range, 1-10).16 Of the remaining two MTX-treated

eyes, one showed progressive disease and one

experienced ocular relapse. In Patient 6, the right eye

initially improved after two injections, but further

treatment was declined, resulting in worsening

vitritis 3 months later. In Patient 5, the left eye

initially presented with neovascular glaucoma. After

14 injections, a complete response was maintained

for 6 months, followed by relapse 9 months later

with anterior chamber infiltrate. Further injections

were challenging due to PCNSL-related organic

psychosis after three additional doses. Despite a

similar number of injections, the ocular relapse rate

in our study (11.1%) was lower than that reported in

a series from the United States (40%) involving seven

patients with an average of six MTX injections,16 and

was comparable to the largest Chinese cohort, where

patients received an average of five injections (10%).6

Keratopathy, the most common adverse effect of

intravitreal MTX,17 18 was mild in our series and

resolved with preservative-free lubricants, bandage

contact lenses, and oral folic acid. The incidence in

our cohort (33%) was lower than the 100% reported in

other studies.4 18 This difference may be attributable

to the lower number of MTX injections, as well as

our practices of compressing the injection site with

a cotton-tipped applicator, performing thorough

saline rinses to minimise corneal exposure, and pre-emptively

prescribing preservative-free lubricants.

Therapeutic role of vitrectomy alone in

primary vitreoretinal lymphoma

Although vitrectomy is pivotal for the diagnosis of

PVRL, its therapeutic role remains controversial.

The largest Chinese study (n=61) demonstrated

complete clearance of malignant cells in 19.7% of

cases after vitrectomy alone,6 whereas the largest

study in a Western population (n=150)19 found

no difference in outcomes between vitrectomised

and non-vitrectomised eyes. In our study, eight

eyes underwent vitrectomy alone without MTX.

A complete response was observed in six of eight

eyes (75%). One patient with isolated ocular PVRL

(Patient 8) achieved a complete response and visual

improvement (from 20/600 in the right eye and 20/70

in the left eye to 20/30 bilaterally) with vitrectomy

alone; the patient did not receive intravitreal MTX

(due to patient reluctance) or systemic chemotherapy

with or without radiation therapy. This response was

maintained at the latest follow-up, 29 months and 5

months after vitrectomy in the right and left eyes,

respectively.

It is plausible that vitrectomy removed

the vitreous scaffold necessary for lymphocyte

proliferation and concurrently reduced the tumour

burden.19 This process may have enabled effective

tumour control by the host immune system, a

mechanism described in rare reports of spontaneous

regression of PVRL.20 Nevertheless, regular

monitoring is recommended, and treatment should

be initiated if any new chorioretinal infiltrates or

vitreous opacities are detected. Given the favourable

visual improvement observed in patients treated with

vitrectomy alone (62.5%), therapeutic vitrectomy

may be considered in those who are intolerant of, or

unwilling to, undergo weekly MTX injections.

Conclusion and future directions

This study represents the first and largest series

to date describing the diagnosis and treatment

outcomes of PVRL in Hong Kong. To address the

low positivity rate of cytological testing, there is

a need for heightened clinical suspicion, greater

awareness of sensitive adjunctive tests, and

enhanced communication among ophthalmologists,

oncologists, and cytopathologists to improve

diagnostic accuracy in suspected PVRL cases or when

initial results are equivocal. Despite the retrospective

design and limited sample size, attributable to the

rarity of PVRL, our findings align with emerging

evidence suggesting that fewer intravitreal MTX

injections or therapeutic vitrectomy alone, followed

by observation, can be effective, particularly in

patients who are frail or intolerant of intensive

injection regimens. Future research should prioritise

prospective randomised studies to identify optimal

treatment strategies that preserve vision and quality of life in patients with PVRL.

Author contributions

Concept or design: ACY Mak.

Acquisition of data: ASH Chee.

Analysis or interpretation of data: ASH Chee.

Drafting of the manuscript: ASH Chee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: ACY Mak, KW Kam, MSC Li, M Ho, ME Brelen, LJ Chen, WWK Yip, AL Young.

Acquisition of data: ASH Chee.

Analysis or interpretation of data: ASH Chee.

Drafting of the manuscript: ASH Chee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: ACY Mak, KW Kam, MSC Li, M Ho, ME Brelen, LJ Chen, WWK Yip, AL Young.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflict of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency

in public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Raval V, Binkley E, Aronow ME, Valenzuela J, Peereboom DM,

Singh AD. Primary central nervous system lymphoma–ocular variant: an interdisciplinary review on management.

Surv Ophthalmol 2021;66:1009-20. Crossref

2. Riemens A, Bromberg J, Touitou V, et al. Treatment

strategies in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: a 17-center European collaborative study. JAMA Ophthalmol

2015;133:191-7. Crossref

3. Huang RS, Mihalache A, Popovic MM, et al. Diagnostic

methods for primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: a systematic

review. Surv Ophthalmol 2024;69:456-64. Crossref

4. Habot-Wilner Z, Frenkel S, Pe’er J. Efficacy and safety of

intravitreal methotrexate for vitreo-retinal lymphoma—20

years of experience. Br J Haematol 2021;194:92-100. Crossref

5. Mohammad M, Andrews RM, Plowman PN, et al.

Outcomes of intravitreal methotrexate to salvage eyes with

relapsed primary intraocular lymphoma. Br J Ophthalmol

2022;106:135-40. Crossref

6. Zhou N, Xu X, Liu Y, Wang Y, Wei W. A proposed protocol

of intravitreal injection of methotrexate for treatment of

primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Eye (Lond) 2022;36:1448-55. Crossref

7. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong. Hong Kong Cancer

Registry, 2021. Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/overview/Overview%20of%20HK%20Cancer%20Stat%202021.pdf . Accessed 15 Feb 2025.

8. Lee SF, Evens AM, Ng AK, Luque-Fernandez MA.

Socioeconomic inequalities in treatment and relative

survival among patients with diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma: a Hong Kong population-based study. Sci Rep

2021;11:17950. Crossref

9. Zhang X, Zhang Y, Guan W, et al. Development of

diagnostic recommendations for vitreoretinal lymphoma.

Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2024;32:1142-9. Crossref

10. Abrey LE, Batchelor TT, Ferreri AJ, et al. Report of an

international workshop to standardize baseline evaluation

and response criteria for primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin

Oncol 2005;23:5034-43. Crossref

11. Whitcup SM, de Smet MD, Rubin BI, et al. Intraocular

lymphoma. Clinical and histopathologic diagnosis.

Ophthalmology 1993;100:1399-406. Crossref

12. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong. List of Private Services,

2024. Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/fnc/pathology.aspx?lang=ENG. Accessed 15 Feb 2025.

13. Peterson K, Gordon KB, Heinemann MH, DeAngelis LM.

The clinical spectrum of ocular lymphoma. Cancer

1993;72:843-9. Crossref

14. Hiemcke-Jiwa LS, Ten Dam-van Loon NH, Leguit RJ,

et al. Potential diagnosis of vitreoretinal lymphoma by detection of MYD88 mutation in aqueous humor with

ultrasensitive droplet digital polymerase chain reaction.

JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:1098-104. Crossref

15. Demirci H, Rao RC, Elner VM, et al. Aqueous humor–derived MYD88 L265P mutation analysis in vitreoretinal

lymphoma: a potential less invasive method for diagnosis

and treatment response assessment. Ophthalmol Retina

2023;7:189-95. Crossref

16. Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT, Wilson DJ, et al. Role of

intravitreal methotrexate in the management of primary

central nervous system lymphoma with ocular involvement.

Ophthalmology 2002;109:1709-16. Crossref

17. Frenkel S, Hendler K, Siegal T, Shalom E, Pe’er J. Intravitreal

methotrexate for treating vitreoretinal lymphoma: 10 years

of experience. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:383-8. Crossref

18. Anthony CL, Bavinger JC, Shantha JG, et al. Clinical

outcomes following intravitreal methotrexate for primary

vitreoretinal lymphoma. Int J Retina Vitreous 2021;7:72. Crossref

19. Liberman P, Francis JH, Mehrotra K, et al. Clinical

outcomes in vitrectomized versus non-vitrectomized eyes

in patients with primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Ocul

Immunol Inflamm 2023;31:496-500. Crossref

20. Kase S, Namba K, Jin XH, Kubota KC, Ishida S. Spontaneous

regression of intraocular lymphoma. Ophthalmology

2012;119:1083-4. Crossref