Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 30 Jan 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Validation of diagnosis codes for pleural diseases

and procedure codes for relevant respiratory

procedures in a healthcare database in Hong

Kong: a single tertiary centre study

Ken KP Chan, MB, ChB, FRCP1,2; Timothy CC Ng, BSc1; CY Sze, BSc1; KC Ling, MPH1; Christopher Chan, MB, ChB, MRCP1; Charlotte HY Lau, MB, ChB, MRCP1; Stephanie WT Ho, MB, ChB, MRCP1; Joyce KC Ng, MB, ChB, FHKCP1; Rachel LP Lo, MB, ChB, FHKCP1; WH Yip, MB, ChB, FHKCP1; Jenny CL Ngai, MB, ChB, FRCP1; KW To, MB, ChB, FRCP1; Fanny WS Ko, MD, FRCP1; David SC Hui, MD, FRCP1

1 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Li Ka Shing Institute of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof David SC Hui (dschui@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: There are insufficient population-based

epidemiological data on various pleural

diseases in Hong Kong. We aimed to validate ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases,

Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) codes for

pleural diseases and relevant procedures prior to

conducting epidemiological analyses using local

electronic health records.

Methods: Hospitalisation episodes coded as

‘pneumothorax’, ‘pleural effusion’, and trauma-related

pleural events, as well as procedures

beginning with ICD-9-CM codes 33 and 34 between

2013 and 2022, were retrieved from the Hospital

Authority. Paediatric patients and uninterrupted

hospitalisation episodes were excluded. The cohort

was filtered to include those hospitalised at Prince

of Wales Hospital (PWH). Up to 50 hospitalisation

episodes were randomly selected for manual

validation. Positive predictive values (PPVs) with

95% confidence intervals of individual codes were

calculated; successful validation was defined as a

PPV ≥0.700. The primary endpoint was the PPV of

individual diagnosis and procedure codes.

Results: A total of 26 757, 218 018, 1269, 185 154,

and 106 450 hospitalisation episodes with non-traumatic

pneumothorax, non-traumatic pleural

effusion, trauma-related pleural events, procedures

with code 33, and procedures with code 34,

respectively, were retrieved. Within the PWH

cohort, PPVs for these diagnosis and procedure

codes were 0.853 (0.787-0.904), 0.928 (0.903-0.948), 0.957 (0.907-0.981), 0.932 (0.913-0.948), and 0.933

(0.916-0.948), respectively. Procedures involving

indwelling pleural catheterisation and open drainage

of the pleural cavity failed validation due to frequent

miscoding.

Conclusion: This is the first validation study of

clinical codes for pleural diseases and related

procedures in Hong Kong. All diagnosis codes and

most procedure codes were successfully validated.

New knowledge added by this study

- This is the first validation study of clinical codes (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) for pleural diseases and relevant procedures in Hong Kong.

- All diagnosis codes and most procedure codes were successfully validated.

- Duplication of codes for similar diagnoses or procedures was identified.

- With the emergence of new respiratory procedures, diagnosis and procedure codes should be updated regularly.

- Removal or consolidation of duplicated subcodes in the Hospital Authority system is necessary to facilitate accurate future research and analysis using clinical codes.

- Researchers should be reminded to search all relevant diagnosis and procedure codes to minimise missing data when identifying specific diseases or procedures.

Introduction

Pleural diseases are common respiratory conditions

that often require hospital admission and have

shown an increasing incidence.1 2 In the United

States, approximately 1.5 million patients experience

pleural effusion annually, with most cases attributed

to congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and cancer.3 4

A recent multicentre, cross-sectional study in China

estimated the prevalence of pleural effusion at 4684

per 1 million Chinese adults.5 In that study, the most

common causes were parapneumonic effusion and

empyema (25.1%), malignant neoplasms (23.7%), and

tuberculosis (12.3%).5 The median hospitalisation

cost was ¥15 534.5 (interquartile range, 9447.2-29 000.0).5 Additionally, an increasing trend in

admissions for spontaneous pneumothorax has been

observed in England, highlighting the prevalence of

the disease and its associated healthcare burden.2

Management of pleural diseases involves

various diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that

extend beyond the pleural space to include the airway

and lung parenchyma. Whether closed or open, these

procedures substantially contribute to the overall

healthcare burden. However, information about

pleural diseases and related respiratory procedures

in Hong Kong remains limited, highlighting the need for contemporary, population-based epidemiological data.

The Hospital Authority, which provides

healthcare services to over 90% of Hong Kong’s

population, maintains extensive healthcare

databases. These include the Clinical Management

System (CMS) and the Clinical Data Analysis and

Reporting System (CDARS), which capture a wide

range of longitudinal clinical data. Examples include

hospital discharge records, diagnosis and procedure

codes for each hospitalisation episode, radiological

findings, and laboratory parameters, particularly

blood and pleural fluid analyses. This comprehensive

dataset provides valuable insights into the burden of

pleural diseases and accurately represents the local

population.

Before analysing diseases and procedures using

administrative data, it is essential to validate the

accuracy of diagnosis and procedure codes within

the healthcare database. These codes are typically

entered by attending physicians, interventionists, or

surgeons performing the procedures, which suggests

a high degree of reliability. However, no prior local

validation study has been conducted. Therefore,

we aimed to assess whether diagnosis codes for

pleural diseases and procedure codes for relevant

respiratory procedures are accurately recorded for

each hospitalisation episode within the Hospital

Authority systems.

Methods

This retrospective, observational validation study of

diagnosis and procedure codes utilised data from a

territory-wide healthcare database in Hong Kong.

Clinical data were obtained from CDARS, provided

by the Hospital Authority. Hospitalisation episodes

with the targeted diagnosis and procedure codes

between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2022

were retrieved from the system. Each observation

represented a hospitalisation episode rather than

a unique patient, and no patient recruitment was

involved.

Diagnosis and procedure codes were defined

using the International Classification of Diseases,

Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

The basic format of an ICD-9-CM code consists of

three to six digits. The Hospital Authority further

extends these codes with additional characters

after the decimal point to specify particular

diagnoses or procedures within an ICD-9-CM

code subgroup (‘subcodes’). These subcodes are

displayed in CDARS but are not typically accessible

to frontline CMS users. All hospitalisation episodes

in acute hospitals with a discharge diagnosis code

of pneumothorax (codes starting with 512), pleural

effusion (codes starting with 012, 197.2, 220.4, 510,

or 511), traumatic pneumothorax or haemothorax

(trauma-related pleural events, codes starting with 860), or procedure codes for relevant respiratory

procedures (codes starting with 33 or 34) were

retrieved, regardless of their position in the coding

list. Hospitalisation episodes for patients younger

than 18 years or from paediatric departments were

excluded from subsequent validation analyses.

Uninterrupted hospitalisation episodes following

the index episodes, including those in acute or

convalescent hospitals with the same diagnosis

code of interest, were also excluded, as these may

represent duplicate entries for the same clinical

event. The remaining hospitalisation episodes after

exclusions were grouped as the main cohort.

Manual verification of a proportion of the

retrieved diagnosis and procedure codes, down to

the subcode level, was conducted to ensure data

accuracy. The main cohort was first filtered to

include only hospitalisation episodes at the authors’

affiliated institution, Prince of Wales Hospital

(PWH), forming the PWH cohort. A maximum of

50 hospitalisation episodes for each diagnosis or

procedure code were randomly extracted from the

PWH cohort to estimate the true positive predictive

values (PPVs) within a 13% margin of error at a

95% confidence interval (95% CI). This precision

level was chosen pragmatically to balance statistical

rigour with the substantial manual effort required for

chart review in this validation study. Prince of Wales

Hospital is a tertiary care centre with a complex case

mix, encompassing a wide range of pleural diseases

and advanced respiratory procedures. Within the

PWH cohort, the types of pleural disease (pleural

effusion, pneumothorax, and trauma-related pleural

events) and their underlying aetiologies (eg, non-tuberculous

infection, tuberculosis, and malignancy)

were determined through retrospective review of

clinical notes, discharge summaries, radiological

findings, and blood and pleural fluid analysis

results using the CMS. Procedure codes were

verified by reviewing procedure records within the

corresponding hospitalisation episodes. All cases

were independently reviewed by two board-certified

respiratory physicians. Discrepancies were resolved

through joint case review until consensus was

reached. Coding accuracy was expressed as PPVs

with 95% CIs. The PPV was calculated by dividing the

number of true positives (ie, hospitalisation episodes

in the PWH cohort where diagnosis and procedure

codes were confirmed by manual verification) by the

total number of true positives and false positives (ie,

episodes where codes were rejected upon manual

review). The 95% CI was calculated using the exact

binomial method.

We hypothesised that the PPVs for the accuracy

of diagnosis and procedure codes would be equal to

or greater than 0.700, a commonly used threshold for

successful validation.6 7 8 The primary endpoint was

the determination of PPVs for the listed diagnosis and procedure codes. All statistical analyses were

performed using Python (version 3.12.6).

Results

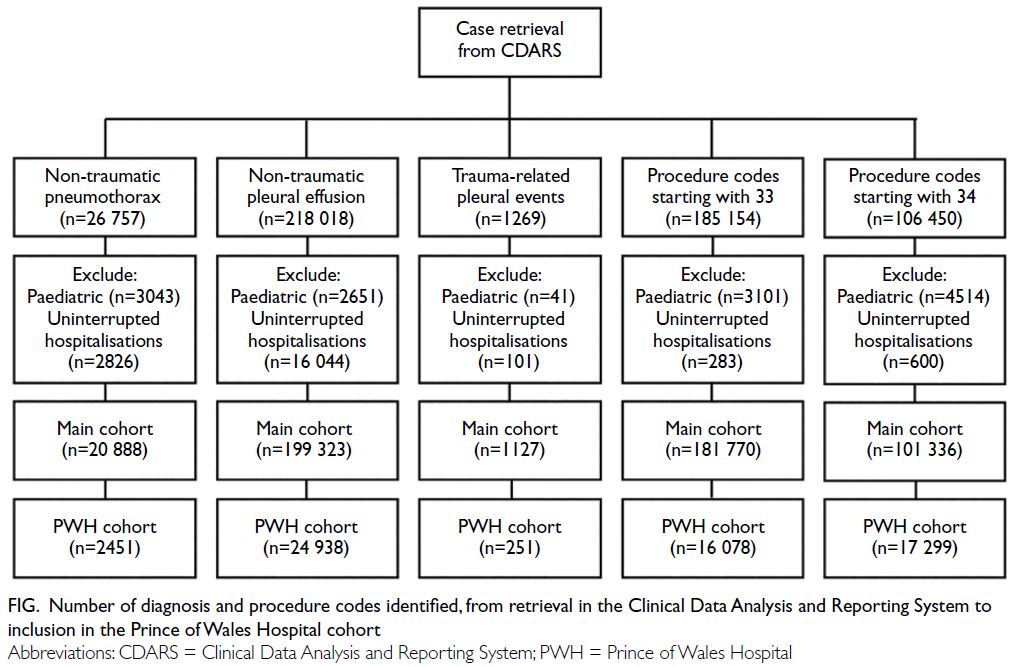

A total of 26 757 non-traumatic pneumothorax,

218 018 non-traumatic pleural effusion, and 1269

trauma-related pleural events were retrieved from

CDARS between 2013 and 2022. Following the

exclusion of paediatric patients and uninterrupted

hospitalisation episodes, 20 888 non-traumatic

pneumothorax, 199 323 non-traumatic pleural

effusion, and 1127 trauma-related pleural events

remained in the main cohort. Of these, 2451 (11.7%),

24 938 (12.5%), and 251 (22.3%) diagnosis codes

for non-traumatic pneumothorax, non-traumatic

pleural effusion, and trauma-related pleural events,

respectively, were identified from PWH (Fig).

Additionally, 185 154 and 106 450 relevant respiratory

procedures with ICD-9-CM codes starting with 33

and 34, respectively, were retrieved. After exclusions,

181 770 and 101 336 procedure codes remained, of

which 16 078 (8.8%) and 17 299 (17.1%) procedure

codes, respectively, were identified from PWH (Fig).

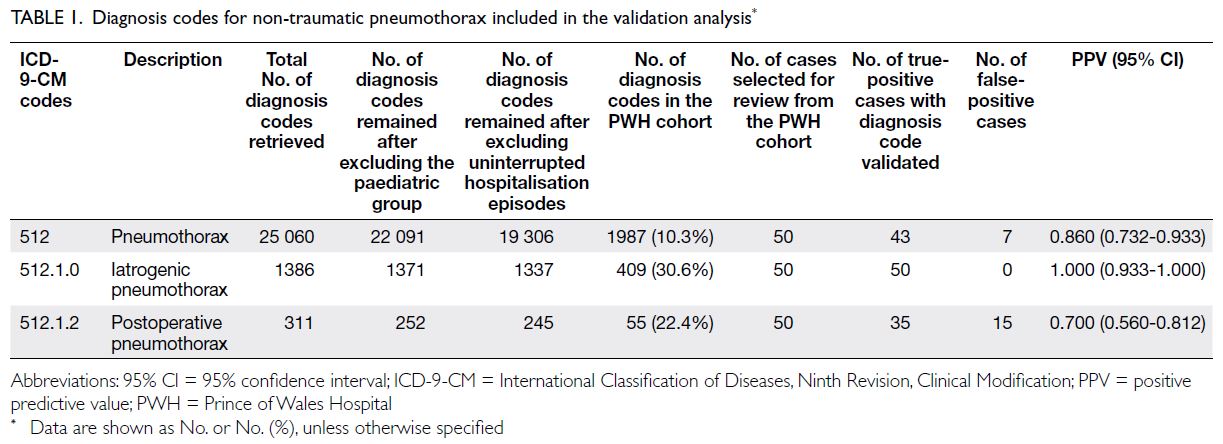

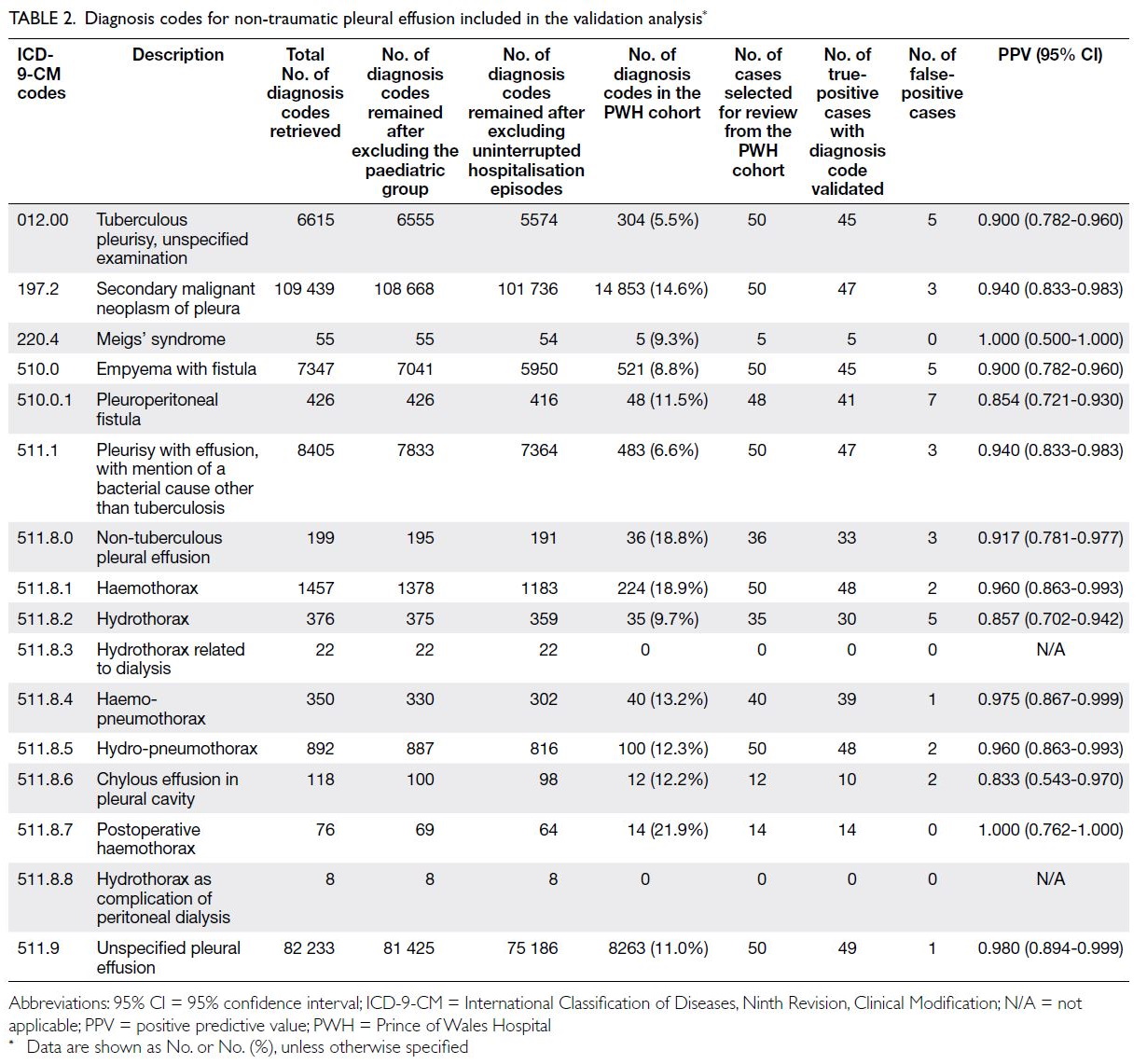

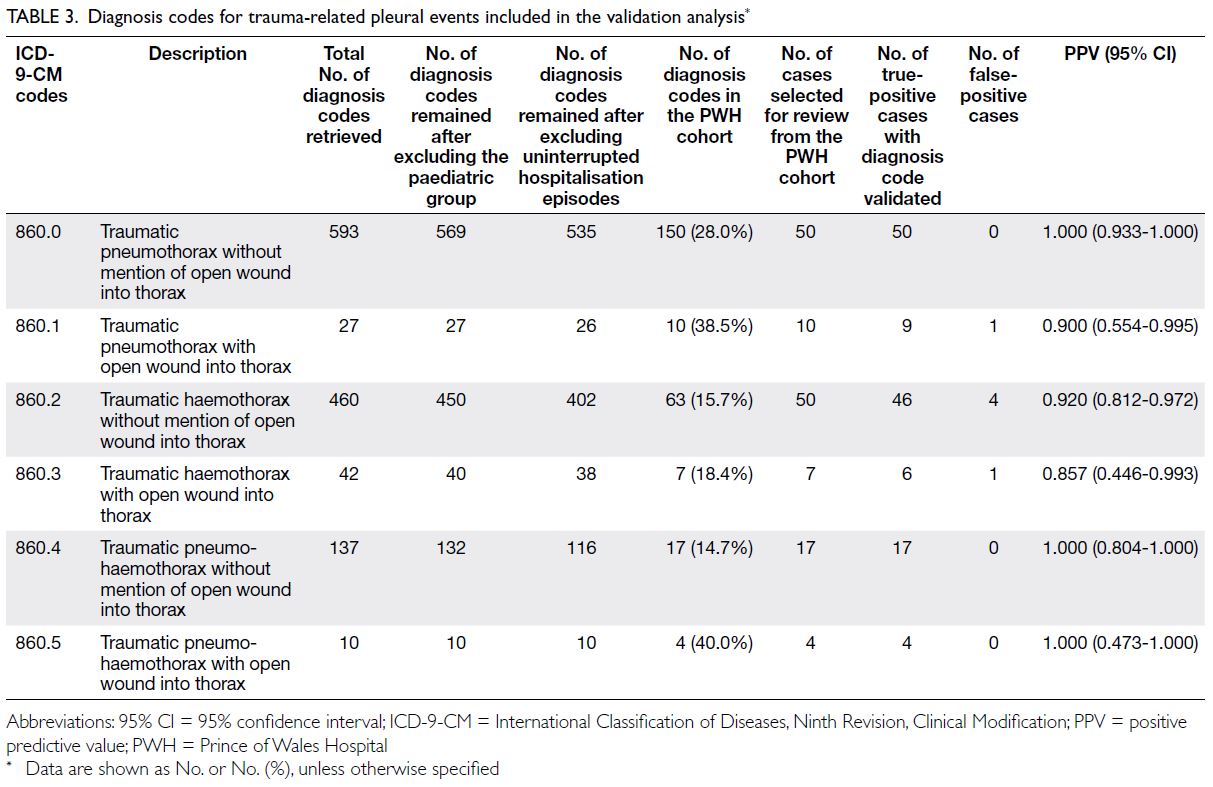

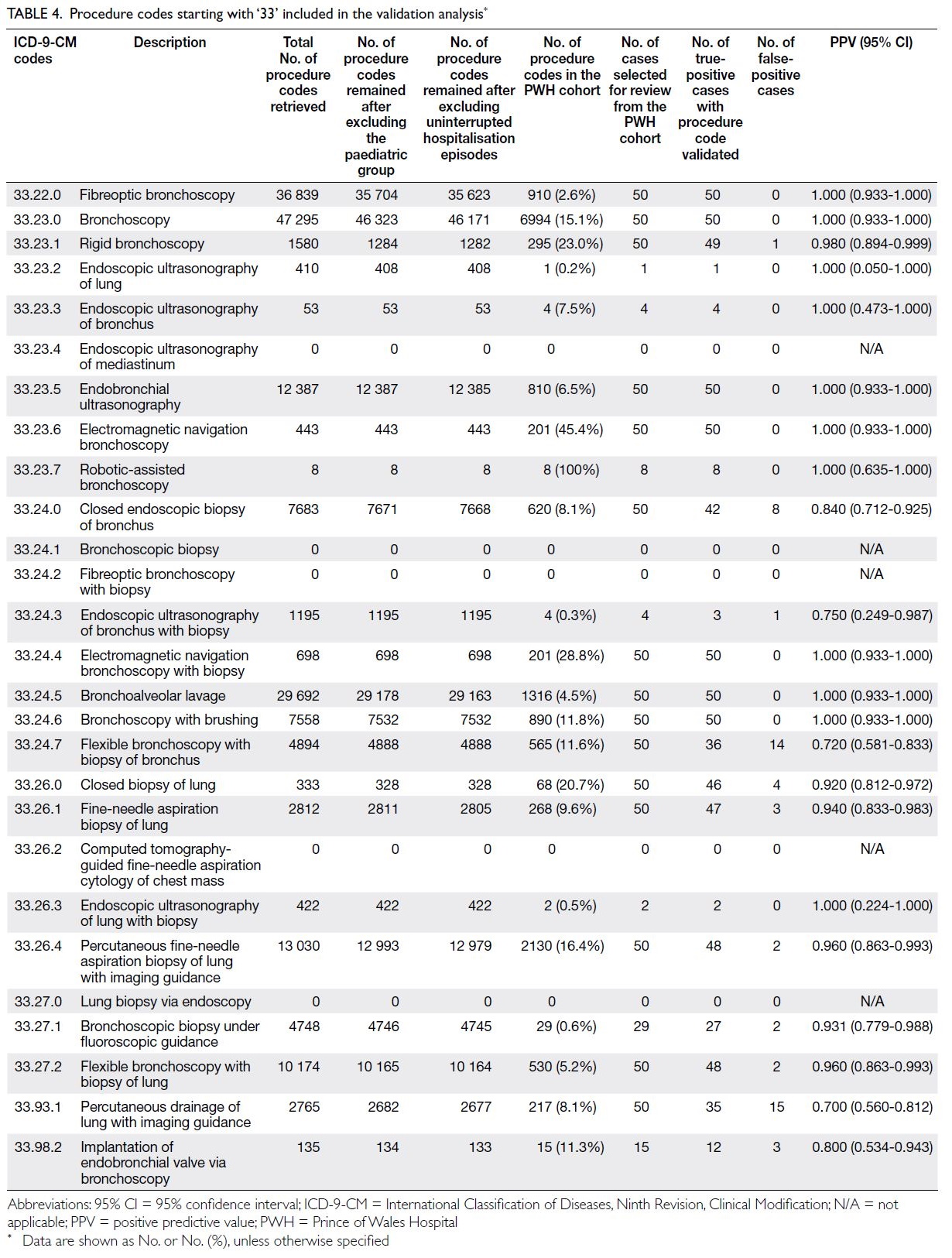

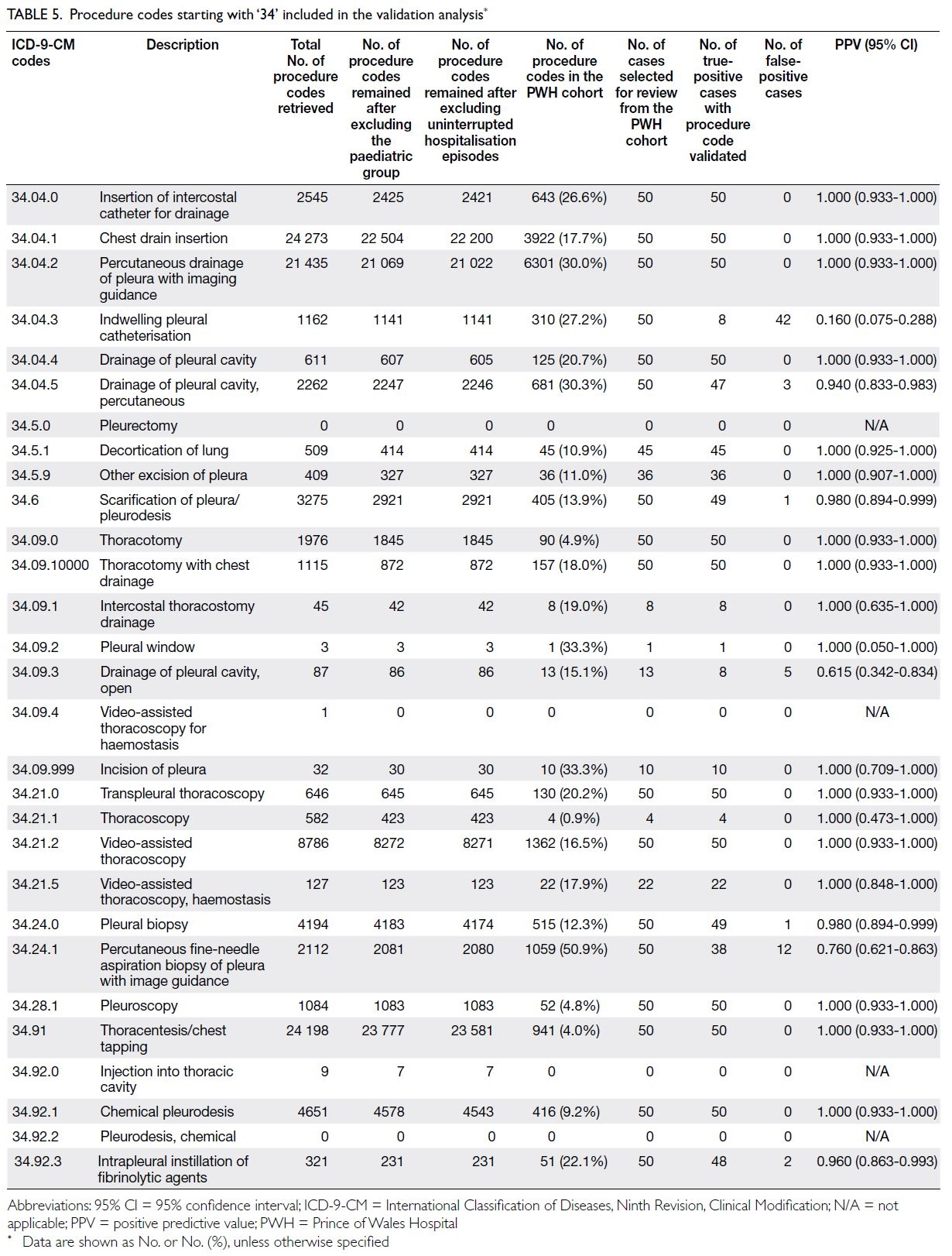

Tables 1, 2, and 3 list the diagnosis codes included in the

validation analysis for non-traumatic pneumothorax

(Table 1), non-traumatic pleural effusion (Table 2)

and trauma-related pleural events (Table 3), while

Tables 4 and 5 present the procedure codes starting

with ‘33’ and ‘34’, respectively; the breakdown of

hospitalisation episodes retrieved using these codes,

and the numbers remaining after screening, are also

shown.

Figure. Number of diagnosis and procedure codes identified, from retrieval in the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System to inclusion in the Prince of Wales Hospital cohort

The overall PPVs (95% CIs) for pneumothorax,

pleural effusion, trauma-related pleural events, and

all diagnosis codes were 0.853 (0.787-0.904), 0.928

(0.903-0.948), 0.957 (0.907-0.981), and 0.919 (0.898-0.936), respectively. The overall PPVs (95% CIs)

for procedure codes starting with 33, starting with

34, and for all procedure codes were 0.932 (0.913-0.948), 0.933 (0.916-0.948), and 0.933 (0.920-0.944),

respectively.

The PPVs for diagnosis codes related to

pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and trauma-related

pleural events were all equal to or greater

than 0.700, with ranges of 0.700-1.000, 0.833-1.000,

and 0.857-1.000, respectively. The lowest PPV

(95% CI) was observed for postoperative

pneumothorax (procedure code 512.1.2) at 0.700

(0.560-0.812). The highest PPVs were seen for

iatrogenic pneumothorax (procedure code 512.1.0)

and postoperative haemothorax (procedure code

511.8.7), both at 1.000, with 95% CIs of 0.933-1.000

and 0.762-1.000, respectively. The reasons for false-positive

diagnosis codes are summarised in online supplementary Tables 1 to 3, with inappropriate

coding of alternative diseases being the most

common cause.

The PPVs for procedure codes starting with 33

ranged from 0.700 to 1.000. Procedure codes starting

with 34 met the PPV benchmark, except for 34.04.3

(indwelling pleural catheterisation) and 34.09.3

(drainage of the pleural cavity, open). The reasons

for false-positive procedure codes are listed in online supplementary Tables 4 and 5, with inappropriate

coding of alternative but similar procedures being

the most common cause. The low PPV for procedure code 34.04.3 (indwelling pleural catheterisation)

arose from its misuse to represent non-tunnelled

pleural catheter insertion, or to document the

presence of an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC)

inserted during prior hospitalisations. Procedure

code 34.09.3 (drainage of the pleural cavity, open)

failed to meet the PPV benchmark because it was

misused to represent closed pleural drainage by

drain insertion, rather than an open procedure.

Discussion

This study is the first to validate diagnosis and

procedure codes for pleural diseases using a

healthcare database in Hong Kong. All diagnosis

codes for pleural diseases and the majority of

procedure codes for relevant respiratory procedures

met the PPV benchmark of 0.700 or higher. Only

procedure codes 34.04.3 (indwelling pleural

catheterisation) and 34.09.3 (drainage of the pleural

cavity, open) failed to meet the validation criteria.

In 2008, the Hong Kong Thoracic Society

reported the burden of lung disease in Hong Kong

using local data from various governmental sources; however, pleural diseases were not included in the

report.9 Over the subsequent decade, the incidence

rates of individual pleural diseases were studied in

Hong Kong. However, these studies were limited

in scope as they focused on single pleural diseases

(eg, empyema,10 11 12 malignant mesothelioma,13 and

spontaneous pneumothorax14) or were restricted to single-centre settings.10 11

There is a pressing need for contemporary,

population-based epidemiological data covering

various pleural diseases in Hong Kong. A recent

local survey highlighted heterogeneous practices

in the management of pleural diseases among medical clinicians and reflected a lack of awareness

and dedicated service infrastructure for pleural

diseases.15 Given the rapid advancements in

diagnostic strategies and therapeutic options for

pleural diseases,16 an accurate and up-to-date

assessment of their clinical burden is crucial. Such

data provide a foundation for guiding future research,

benchmarking healthcare standards in Hong Kong

against those of other countries, informing the

allocation of future healthcare resources for pleural

diseases, and estimating the workload of healthcare

professionals managing these conditions. All such

service developments should be based on an accurate

estimation of the current burden and projected

future demand. The use of existing healthcare

databases offers a practical approach; however,

relevant diagnosis and procedure codes must first be

validated. A similar research pathway was followed

by Arnold et al,17 who validated diagnosis codes prior

to assessing the epidemiology of pleural empyema in

English hospitals.17 18

Nearly all PPVs of the diagnosis and

procedure codes studied exceeded the benchmark

of 0.700. Notably, PPVs for procedure codes were

generally higher than those for diagnosis codes.

This is because diagnosis codes can be carried over from previous hospitalisation episodes, enabling

attending physicians to select active or inactive

diagnosis codes regardless of their relevance

to the current episode. In contrast, procedure

codes cannot be carried over and must be entered

manually to reflect procedures performed during

the corresponding hospitalisation episode. This

requirement contributes to the higher accuracy for

procedure codes.

The PPV for procedure code 34.04.3 (indwelling

pleural catheterisation) was unexpectedly low due

to misuse. The absence of a specific diagnosis code

indicating the presence of an IPC, combined with the

inclusion of the term ‘pleural’ in the code description,

contributed to its incorrect use, particularly

during searches for non-tunnelled pleural catheter

insertion. Updated diagnosis codes to indicate the

status ‘presence of IPC’, or a new procedure code

for ‘pleural fluid drainage using an existing IPC’,

would accurately reflect the clinical scenario. Once

available, such codes should be validated before any

analyses of IPC use in territory-wide healthcare

databases. Alternatively, establishing a clinical

registry for IPC use could facilitate more accurate

tracking of patients with both malignant and benign

causes of pleural effusion.

Some diagnosis codes (eg, hydrothorax related

to dialysis [511.8.3] and hydrothorax as complication

of peritoneal dialysis [551.8.8]) and procedure codes

(eg, video-assisted thoracoscopy for haemostasis

[34.09.4] and injection into thoracic cavity [34.92.0])

were used in other hospitals but not at PWH;

therefore, they could not be validated in this study.

Within the PWH cohort, alternative diagnosis or

procedure codes were used and validated. However,

the number of hospitalisation episodes associated

with these codes was small, and their impact would

be minimal in a territory-wide healthcare data

analysis where similar codes are grouped together.

Duplication of subcodes for similar diagnoses

or procedures was also noted. Several diagnoses and

procedures were represented by different codes,

including:

Researchers should be reminded to search all

relevant diagnosis and procedure codes to minimise

the risk of missing data for specific diseases or

procedures during code searches. In the long term,

reconciling similar codes may help reduce ambiguity

and improve data consistency.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, notably its status

as the first validation study conducted using

a large healthcare database in Hong Kong. It

successfully validated codes for a wide range of

pleural diseases and respiratory procedures, thereby

laying the foundation for future epidemiological

research. However, several limitations should be

acknowledged. Not all codes could be adequately

validated due to their small case volumes in the PWH

cohort. For example, codes for Meigs’ syndrome

(220.4), traumatic pneumothorax with open wound

into thorax (860.1), and traumatic haemothorax with open wound into thorax (860.3) had small numbers

even in the overall cohort, and some codes were

duplicated. As such, future research incorporating

patient searches based on these diagnosis and

procedure codes should take these limitations

into account. The single-centre nature of the study

represents a further limitation, as disease patterns

and coding practices may vary across district general

hospitals.

Conclusion

This is the first validation study of diagnosis codes

for pleural diseases and procedure codes for

relevant respiratory procedures using a territory-wide

healthcare database in Hong Kong. All

diagnosis codes and the majority of procedure

codes demonstrated high PPVs, indicating accurate

coding. Given the emergence of new respiratory

procedures, diagnosis and procedure codes should

be regularly updated. The removal or consolidation

of duplicated subcodes within the Hospital Authority

system is also necessary to facilitate accurate future

research and analysis using clinical codes. Further

evaluation and harmonisation of coding practices

across different hospitals would be beneficial. These

measures will pave the way for future territory-wide

studies and enable monitoring of the overall burden

of pleural diseases in Hong Kong.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KKP Chan.

Acquisition of data: KKP Chan, TCC Ng, CY Sze, KC Ling.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KKP Chan, TCC Ng, CY Sze, KC Ling.

Drafting of the manuscript: KKP Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KKP Chan, TCC Ng, C Chan, CHY Lau, SWT Ho, JKC Ng, RLP Lo, WH Yip, JCL Ngai, KW To, FWS Ko, DSC Hui.

Acquisition of data: KKP Chan, TCC Ng, CY Sze, KC Ling.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KKP Chan, TCC Ng, CY Sze, KC Ling.

Drafting of the manuscript: KKP Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KKP Chan, TCC Ng, C Chan, CHY Lau, SWT Ho, JKC Ng, RLP Lo, WH Yip, JCL Ngai, KW To, FWS Ko, DSC Hui.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Prof Terry CF Yip from the Department of Medicine and Therapeutics of The Chinese University of

Hong Kong for providing statistical support.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of

Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2022.031). The

requirement for patient consent was waived by the Committee

due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions or

recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s)

and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine

and the Hong Kong Medical Association. The Hong Kong

Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association

disclaim all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance

placed on the content.

References

1. Bodtger U, Hallifax RJ. Epidemiology: why is pleural disease

becoming more common? In: Maskell NA, Laursen CB,

Lee YCG, et al, editors. Pleural Disease. Vol 87. Schweiz,

Switzerland: European Respiratory Society; 2020: 1-12. Crossref

2. Hallifax RJ, Goldacre R, Landray MJ, Rahman NM,

Goldacre MJ. Trends in the incidence and recurrence of

inpatient-treated spontaneous pneumothorax, 1968-2016.

JAMA 2018;320:1471-80. Crossref

3. Light RW. Pleural effusions. Med Clin North Am 2011;95:1055-70. Crossref

4. Taghizadeh N, Fortin M, Tremblay A. US hospitalizations

for malignant pleural effusions: data from the 2012

National Inpatient Sample. Chest 2017;151:845-54. Crossref

5. Tian P, Qiu R, Wang M, et al. Prevalence, causes, and health

care burden of pleural effusions among hospitalized adults

in China. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2120306. Crossref

6. Kwok WC, Tam TC, Sing CW, Chan EW, Cheung CL.

Validation of diagnostic coding for bronchiectasis in

an electronic health record system in Hong Kong.

Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2023;32:1077-82. Crossref

7. Ye Y, Hubbard R, Li GH, et al. Validation of diagnostic coding for interstitial lung diseases in an electronic health

record system in Hong Kong. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug

Saf 2022;31:519-23. Crossref

8. Kwok WC, Tam TC, Sing CW, Chan EW, Cheung CL.

Validation of diagnostic coding for asthma in an electronic

health record system in Hong Kong. J Asthma Allergy

2023;16:315-21. Crossref

9. Chan-Yeung M, Lai CK, Chan KS, et al. The burden of

lung disease in Hong Kong: a report from the Hong Kong

Thoracic Society. Respirology 2008;13 Suppl 4:S133-65. Crossref

10. Chan KP, Ng SS, Ling KC, et al. Phenotyping empyema by

pleural fluid culture results and macroscopic appearance:

an 8-year retrospective study. ERJ Open Res 2023;9:00534-2022. Crossref

11. Tsang KY, Leung WS, Chan VL, Lin AW, Chu CM.

Complicated parapneumonic effusion and empyema

thoracis: microbiology and predictors of adverse outcomes.

Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:178-86.

12. Chan KP, Ma TF, Sridhar S, Lam DC, Ip MS, Ho PL. Changes

in etiology and clinical outcomes of pleural empyema

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Microorganisms

2023;11:303. Crossref

13. Chang KC, Leung CC, Tam CM, Yu WC, Hui DS, Lam WK.

Malignant mesothelioma in Hong Kong. Respir Med

2006;100:75-82. Crossref

14. Chan JW, Ko FW, Ng CK, et al. Management and prevention

of spontaneous pneumothorax using pleurodesis in Hong

Kong. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:385-90.

15. Lui MM, Yeung YC, Ngai JC, et al. Implementation of

evidence on management of pleural diseases: insights from

a territory-wide survey of clinicians in Hong Kong. BMC

Pulm Med 2022;22:386. Crossref

16. Lui MM, Lee YC. Twenty-five years of respirology:

advances in pleural disease. Respirology 2020;25:38-40. Crossref

17. Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Morris TT, et al. Epidemiology

of pleural empyema in English hospitals and the impact of

influenza. Eur Respir J 2021;57:2003546. Crossref

18. Hamilton F, Arnold D. Accuracy of clinical coding of

pleural empyema: a validation study. J Eval Clin Pract

2020;26:79-80. Crossref