Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 23 Sep 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Parental depression in the relationship between parental stress and child health among low-income families in Hong Kong

Esther YT Yu, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1; Eric YF Wan, PhD, CStat1,2; Rosa SM Wong, PhD3; Ivy L Mak, PhD1; Kiki SN Liu, PhD1; Caitlin HN Yeung, MB, BS, MPH1; Patrick Ip, FRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics)4,5; Agnes FY Tiwari, PhD, FAAN6; Weng Y Chin, FRACGP1; Emily TY Tse, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1; Carlos KH Wong, PhD1,2,7; Vivian Y Guo, PhD8; Cindy LK Lam, MD, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1

1 Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Special Education and Counselling, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 School of Nursing, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

7 Laboratory of Data Discovery for Health Limited, Hong Kong Science Park, Hong Kong SAR, China

8 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Corresponding author: Dr Eric YF Wan (yfwan@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Low-income families face increased

exposure to stressors, including material hardship

and limited social support, which contribute to poor

health outcomes. The poor health and behavioural

problems in children from these families may

exacerbate parental stress. This study explored the

bidirectional relationship between parental stress

and child health, along with its mediators and

moderators, among low-income families in Hong

Kong.

Methods: In total, 217 families were recruited from

two less affluent communities between 2016 and

2017; they were followed up at 12 and 24 months.

Each parent-child pair was assessed using parent-completed

questionnaires on socio-demographics,

medical history, parental stress, health-related

quality of life, child health and behaviour, family

harmony, parenting style, and neighbourhood

cohesion.

Results: Thirty-eight parents (17.5%) reported

significantly higher levels of stress than the control

group. These individuals were more likely to be

single parents (41.2% vs 18.5%), victims of intimate

partner abuse (23.7% vs 10.9%), have a household

income below 50% of the Hong Kong population

median (50.0% vs 29.9%), and be diagnosed with

mental illnesses (23.7% vs 5.1%). A bidirectional

inverse relationship was observed between parental

stress and child health at respective time points,

with cross-effects from baseline child health to later

parental stress, and from baseline parental stress to

later child health. The relationship was mediated by

the level of parental depression.

Conclusion: Parental stress both precedes and

results from child health and behavioural problems, with reciprocal short-term and long-term effects.

Screening and intervention for parental depression

are needed to mitigate the impacts of stress on health

among parents and children.

New knowledge added by this study

- Single parents, victims of intimate partner abuse, individuals with mental illnesses, and/or those living in poverty reported significantly higher levels of stress compared to other low-income parents in Hong Kong.

- A bidirectional inverse relationship was observed between general parental stress and child health over a 24-month period among low-income families in Hong Kong.

- Parental depression mediated the relationship between parental stress and child health.

- Active screening for parental depression among at-risk parents in low-income communities is urgently needed to enable early intervention and reduce long-term negative impacts on child health.

Introduction

Low-income families face increased exposure to

stressors,1 2 such as material hardship, dispossession,

limited social support,3 4 trauma, and violence,1 5

which subsequently affect family relationships

and the physical and mental health of parents,6 7 8

contributing to household-wide feelings of

stigma, isolation, and exclusion. These stressors

are particularly relevant to Hong Kong, where

approximately one-fifth of the population lives

below the poverty line.9 Adults from low-income

families in Hong Kong have reported significantly

lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) than

age- and sex-matched individuals from the general

population; low income is significantly associated

with poorer mental health.10

Stressors may persist across the life course

and affect the next generation, resulting in

intergenerational socio-economic inequality and

health disparities. Early caregiving experiences

have been linked to later-life child health outcomes

through physiological stress responses.11 Moreover,

poor mental health in parents may lead to family

disharmony and maladaptive parenting practices,

which can increase a child’s risk of adverse health

outcomes.7 8 Specifically, children of parents with depression tend to exhibit more difficult

temperaments and diminished psychosocial

functioning.12 13 Children from low-income families

in Hong Kong have reported poorer health and more

behavioural problems relative to population norms

for similar age-groups.14 15 Without adequate parental

care and guidance, such children may be more

vulnerable to academic difficulties and behavioural

problems, thereby exacerbating parental stress. A

bidirectional relationship between parental stress

and child health has been documented in Western

studies6 8 but not within the Chinese context.

Stress coping can be mediated or moderated

by various social factors.16 17 For instance, stressed

parents may contribute to family disharmony, which

mediates diminished child health. Neighbourhood

cohesion may moderate this relationship by

alleviating parental stress and enhancing children’s

well-being. The identification of mediators and

moderators that may influence the relationship

between parental stress and child health enables

development of targeted interventions and policy

recommendations. Despite strong associations of

parental depression with stress18 and child health,12 13

its mediating role in this relationship remains unclear.

A recent study demonstrated mediation between

parental stress and parent-infant bonding,19 but

evidence concerning overall child health is lacking.

This study aimed to explore whether a bidirectional

relationship exists between parental stress and child

health and to identify its mediators and moderators,

with the goal of promoting health among parents

and children from low-income families in Hong

Kong. We hypothesised that parental stress precedes

and results from child health, with mediating and

moderating effects exerted by factors illustrated in

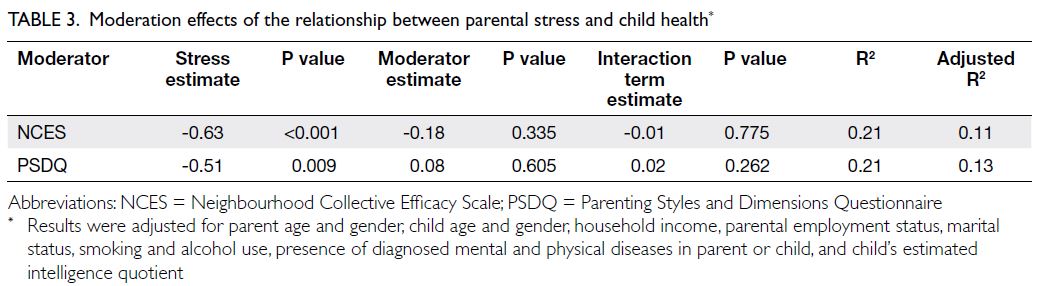

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study concept map based on existing knowledge of the associations of parental, child and family factors with parental stress and child health

Methods

Study design

This prospective cohort study involved 217 parent-child

pairs in which at least one parent was the

primary caregiver and at least one parent was

employed, with a monthly household income lower

than 75% of the Hong Kong median at baseline. This

income criterion included working poor families who

lived above the poverty line (50% of the population

median) and received limited government support.

Families were recruited by research staff when

attending health assessments during our previous

cohort study20 performed in two less affluent Hong

Kong communities between May 2016 and October

2017. Parents unable to communicate in Chinese,

as well as children born prematurely and/or with

congenital deformities, were excluded. All parents

provided written informed consent for themselves

and their child to participate in the study. Sample size was determined based on the need to detect

a difference in Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ)

scores between children of parents with high and low

stress levels, classified according to the Depression

Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) stress subscale scores.

Our previous cohort study showed that average

CHQ general health perceptions subscale scores in

children of parents with high and low DASS stress

subscale scores were 59 (standard deviation [SD]=17)

and 65 (SD=16), respectively20 (effect size=0.4). A

sample size of 200 (100 per group) parent-child

pairs was required to detect a difference of 6 points

in CHQ general health perceptions subscale score

between groups using an independent t test with

80% power and a 5% level of significance.

Data collection

Each parent-child pair was invited to complete a

comprehensive questionnaire survey at three time

points (ie, baseline, 12 months, and 24 months)

covering parental stress, HRQOL, and mental health;

child’s general health, HRQOL, and behaviour;

family harmony; parenting style; and neighbourhood

cohesion, as reported by the parent. Potential

confounders were recorded at baseline, including

parental age, gender, education level, marital status,

employment status, household income, smoking

habits, and alcohol consumption, as well as the

child’s age, gender, estimated intelligence quotient,

and special education needs. Physical and mental co-morbidities

in parents and children were recorded at

all three time points.

Study instruments

Exposure

Parental stress was measured using the stress

subscale of the DASS–21 items questionnaire.21

A cut-off score of ≥15 indicated the presence of

significant parental stress.21 The scale has been validated in a Chinese population.22

Primary outcome

Child health was measured using the general health

perceptions subscale score from the CHQ–Parent

Form 50.23 A higher score indicates better perceived

physical and psychological HRQOL in the child

based on parental proxy report. The Chinese version

has demonstrated good psychometric properties in

local Chinese children.20

Potential mediators/moderators

The Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9)24 was

used to screen for parental depression. A cut-off

score of ≥10 was regarded as clinically significant

depression. The Chinese version of the PHQ-9 was

validated and used in our previous study.20 Family

harmony was measured using the Family Harmony

Scale–Short Form (FHS-5).25 Higher single-factor

harmony scores reflect greater harmony. The Chinese

version has demonstrated good psychometric

properties in local Chinese households.25 Parent-child

interaction was assessed using the Child

Physical Assault and Neglect subscales of the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC).26 Higher scores indicate higher frequencies of respective

issues in the past 12 months. The translated

traditional Chinese version has demonstrated good

psychometric properties.27 Parenting style was assessed using the Authoritative Parenting Style

subscale of the short version of the Parenting Style

and Dimensions Questionnaire.28 A higher score

indicates a stronger tendency towards authoritative

parenting. The questionnaire has been validated

in the Chinese cultural setting.29 Neighbourhood

support was measured using the Neighbourhood

Collective Efficacy Scale.30 Higher scores indicate

greater neighbourhood cohesion. The scale has been

tested in Chinese in a local study.31

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics of parent-child pairs and

their households were summarised using descriptive

statistics. Differences between groups according to

parental stress level were assessed using independent

t tests for continuous variables and the Chi squared

test for categorical variables.

The longitudinal bidirectional relationship

between parental stress and child health was

assessed using a cross-lagged panel model. Multiple

indicators were utilised to evaluate model goodness-of-fit. A statistically non-significant Chi squared

P value, Comparative Fit Index and Tucker-Lewis

Index >0.95, root mean square error of approximation

≤0.05, and standardised root mean residual >0.08

were considered indicative of desirable goodness-of-fit. The final model was selected using root mean

square error of approximation–based forward

stepwise selection.

A mediation model was used to evaluate

candidate mediators. Model estimates were obtained

using 5000 bootstrapping samples. A statistically

significant indirect effect, along with a reduced direct

effect magnitude relative to the total effect, indicated

that a given mediator explained the relationship

between parental stress and child health.32 A multi-mediator

model was constructed; differences in

indirect effects between mediators were estimated

via pairwise comparison.

Potential moderating effects of neighbourhood

cohesion and parenting style on the relationship

between parental stress and child health were

examined by multivariable linear regression. A

statistically significant interaction term coefficient

indicated a moderation effect. All variables were

centred to a mean of zero to reduce multicollinearity

related to interaction terms. Confounders were

included to improve model goodness-of-fit; R2 and

adjusted R2 values were used to evaluate model

performance.

All descriptive analyses were performed using

Stata 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station [TX],

US); all model analyses were carried out using the lavaan package33 version 0.6-6, in R version 4.0.1

(R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna,

Austria). Data completion rates are presented

in online supplementary Table 1. Complete case

analyses were conducted. All tests were two-tailed; P

values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

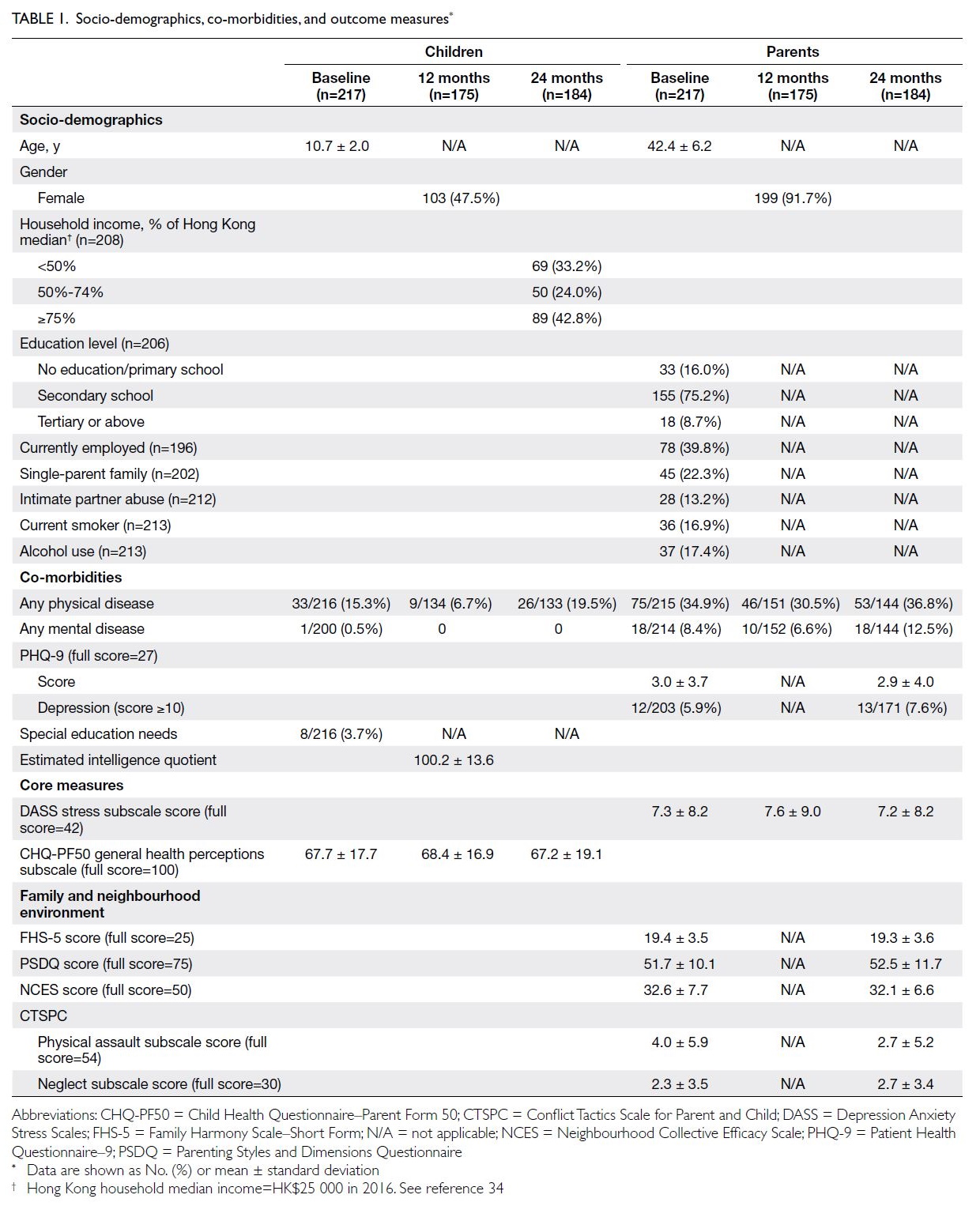

Among the 217 parent-child pairs recruited at

baseline, 175 (80.6%) and 184 (87.6%) pairs attended

the 12-month and 24-month follow-ups, respectively

(online supplementary Fig 1). Their characteristics at

each of the three time points are detailed in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of parent-child pairs

At baseline, the ages of parents and children (mean ± SD) were 42.4 ± 6.2 years and 10.7 ± 2.0 years,

respectively. Approximately half of the children

were girls (47.5%), whereas the parents involved

were predominantly mothers (91.7%). The majority

(75.2%) of parents had completed secondary

education. Approximately 39.8% of primary parents

were employed, and 57.2% of families had a monthly

household income below 75% of the 2016 Hong

Kong median (ie, HK$25 000).34

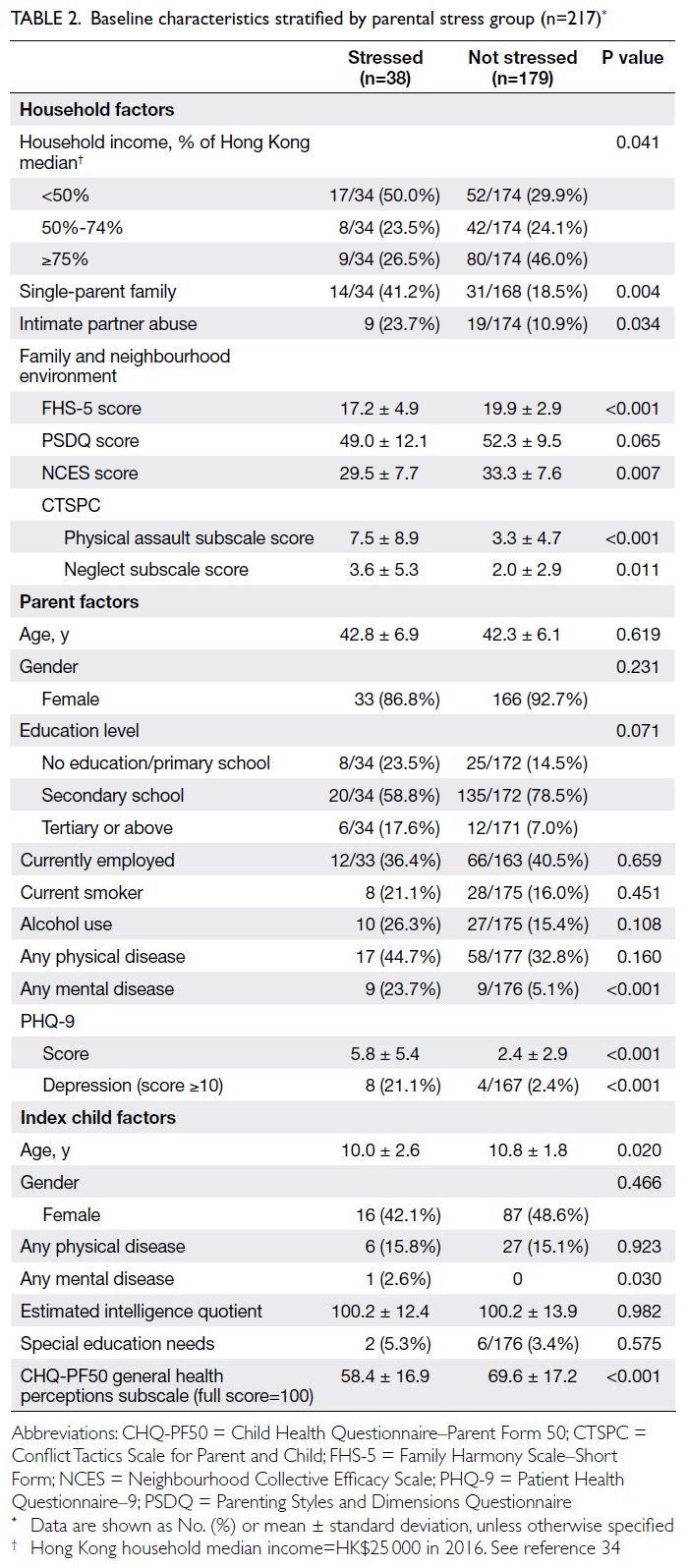

Thirty-eight parents (17.5%) experienced

significant stress, indicated by a DASS stress

subscale score of 15 or above at baseline.

Considerable differences were evident in their

baseline characteristics compared with parents who

were not stressed. Stressed parents were more likely

to be single parents (41.2% vs 18.5%) and to have

a household income below 50% of the Hong Kong

median (50.0% vs 29.9%). A greater proportion of

stressed parents reported being victims of intimate

partner abuse (23.7% vs 10.9%). Diagnosed mental

illnesses (23.7% vs 5.1%) and depression, indicated

by a PHQ-9 score ≥10 (21.1% vs 2.4%), were more

prevalent among these parents (Table 2). Both their

physical and mental HRQOL were significantly

worse (physical component score=42.5 ± 9.9 vs

49.1 ± 8.2; mental component score=38.1 ± 10.0 vs

55.5 ± 8.7; P<0.001).

Compared with children of parents who were

not stressed, children of stressed parents were

younger (age=10.0 ± 2.6 years vs 10.8 ± 1.8 years;

P=0.020) and had worse general health and HRQOL,

as reflected by lower scores in every subscale of the

CHQ–Parent Form 50 except bodily pain and self-esteem.

In particular, large differences were observed

in four subscales: parental impact—emotional,

parental impact—time, family activities, and family

cohesion.

Moreover, stressed parents reported lower

scores in family harmony (FHS-5) and neighbourhood

cohesion (Neighbourhood Collective Efficacy Scale).

Although parenting style did not differ significantly, stressed parents showed a greater tendency for

physical punishment, as reflected by higher scores

on the CTSPC–physical assault subscale, and for

neglect, as indicated by higher CTSPC–neglect

subscale scores, compared with parents who were

not stressed (Table 2).

Relationship between parental stress and

child health over time

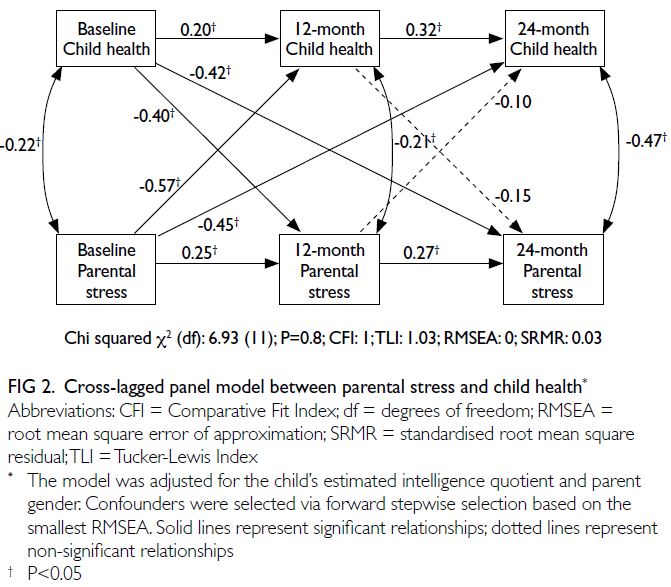

Figure 2 shows the cross-lagged panel model

examining the bidirectional relationship between

parental stress and child health. A bidirectional

relationship between child health and parental

stress was confirmed. Significant associations

were observed between parental stress and

child health at each time point (estimates:

baseline=-0.22, 12 months=-0.21, 24 months=-0.47); between baseline child health and parental

stress at 12 months (estimate=-0.40) and 24 months

(estimate=-0.42); and between baseline parental

stress and child health at 12 months (estimate=-0.57)

and 24 months (estimate=-0.10).

Mediators and moderators of the parent-child

health relationship over time

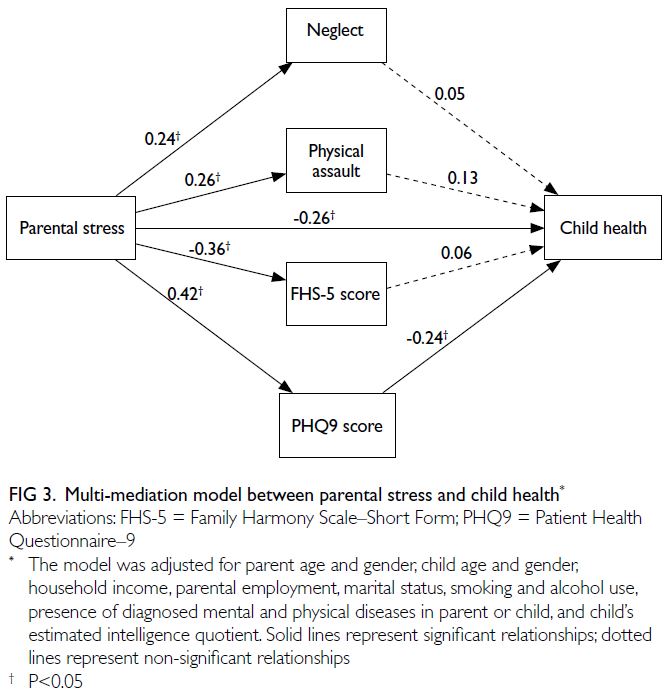

The multi-mediation model results generated by

bootstrapping are illustrated in Figure 3; the model

estimates and goodness-of-fit statistics are presented

in online supplementary Table 2. The total effect of

the relationship between parental stress and child

health was reduced when mediators were included

in the model. Significant positive associations of

parental stress were observed with the PHQ-9 score,

as well as the physical assault and neglect subscales

of the CTSPC. A significant negative association

was noted between parental stress and the FHS-5

score. Among mediators, only the PHQ-9 exerted a

significant negative effect on child health.

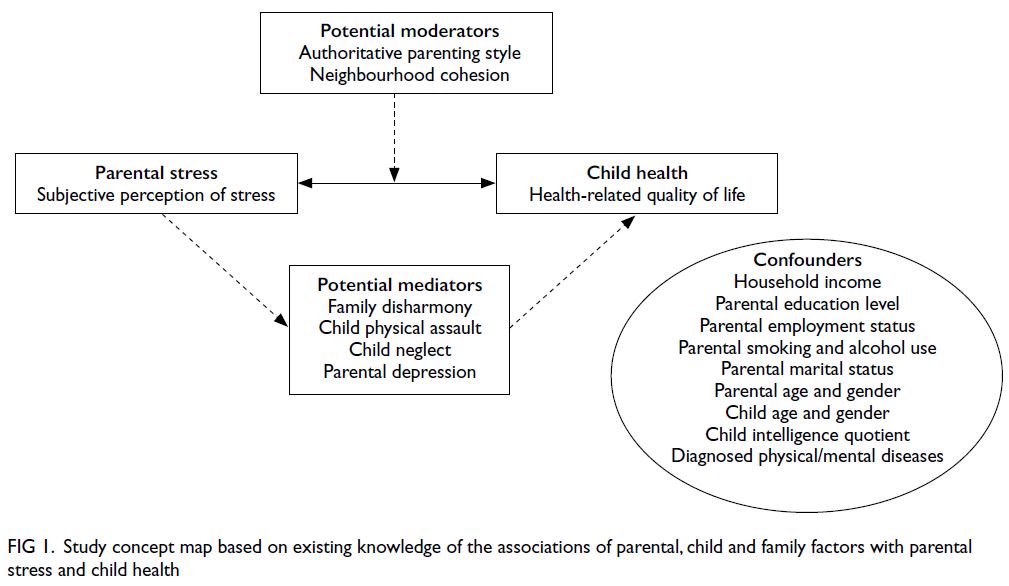

Table 3 presents the moderation model.

Neither neighbourhood cohesion nor parenting style

demonstrated a moderating effect on the relationship

between parental stress and child health. Estimates

for the interaction terms were negligible. The R2

values were around 0.21, and the adjusted R2 values

were slightly lower (0.11-0.13), indicating modest

explanatory power of the model after adjusting for

confounders.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that a substantial

proportion of low-income parents experienced

stress (17.5%), which was associated with multiple

stressors including poverty, marital problems,

intimate partner abuse, family disharmony, and

reduced neighbourhood support. Children of

stressed parents reported worse general health and

HRQOL, as well as more behavioural problems. A short-term and long-term bidirectional inverse

relationship between parental stress and child

health was confirmed; this relationship was partially

mediated by the level of parental depression.

Compared with the general Hong Kong

population, the parent-child pairs in this study

were more exposed to various known stressors in

addition to low income. The prevalences of single-parent

families (22.3% vs 9.8%35) and intimate

partner abuse (13.2% vs 7.2%36) were higher, and

more parents reported regular alcohol consumption

(17.4% vs 8.7%37). Therefore, it is not surprising that

a considerably greater proportion of parents in this

study experienced elevated levels of stress (17.5%

vs 5.2%38) and depression (5.9% vs 1.2%37). The

persistently high level of parental stress observed

during the study period may be attributed partly

to ongoing exposure to various stressors over time

and partly to constant exposure to chronic stressors.

Both scenarios highlight the urgent need to ensure

assessment and intervention for these disadvantaged

parents.

Previous studies have demonstrated

bidirectional interactions between parental stress

and child health in relation to both internalising and

externalising behaviours.6 8 Increases in behavioural

problems have been shown to raise parental stress

over time, which in turn exacerbates behavioural

issues in children.39 Our study adds to this body of

evidence by confirming significant bidirectional

effects between general parental stress and child

health at each time point. Cross-effects were

observed from baseline child health to later parental

stress, and from baseline parental stress to later child

health at both 12 and 24 months. These findings

suggest that parental stress both precedes and

results from child health, with reciprocal short-term

and long-term influences.40

In our attempt to identify pathways through

which parental stress affects child health, we

observed that only parental depression significantly

mediated the relationship. This result is consistent

with previous findings that maternal depression and

perceived stress directly and negatively influence

child development.41 One possible explanation is that

depressed mothers may lack the energy or capacity

to provide adequate care and support for their child’s

health. Research into this mediation effect remains

limited; however, one recent study reported similar

outcomes regarding the indirect impact of workrelated

stress on child health, mediated by maternal

depression.42 The implementation of screening

and intervention for parental depression is both

imperative and urgent to counteract the adverse

effects of stress on parental and child health. Medical

and social service providers should collaborate to

actively screen at-risk parents from low-income

families in the community. Early intervention through lifestyle-based care—such as physical

activity, relaxation techniques, and mindfulness-based

therapies—can help to prevent43 44 and

manage45 46 depression, thus mitigating long-term

negative impacts on child health.

However, it must be noted that parents with

depression may be biased towards over-reporting

their child’s problems,47 compared with other

informants such as teachers and the children

themselves.48 Further research is warranted to

identify individual and family characteristics that

may influence discrepancies between informants.

Other potential factors examined in previous

studies—such as household structure (dual- vs

multi-generational), parental rearing behaviours,

and confident and affective social support—might

also contribute to the relationship between parental

stress and child health; they should be explored in

future studies with larger sample sizes.

Strengths and limitations

This is one of the first studies to examine the longitudinal relationship between general parental

stress and child health, enabling assessment of

possible causal relationships between the two

outcomes. Specifically, we recruited vulnerable

families with substantial socio-economic

disadvantages who experience high levels of stress

and would benefit most from future interventions.

Furthermore, a high response rate was maintained

throughout the study, ensuring adequate power for

the analyses.

However, the findings of our study must be

interpreted in light of the following limitations. First,

although we conducted a comprehensive analysis of

factors related to parental stress and child health, the

outcomes were based on self-reported assessments,

which are susceptible to respondent bias. Only three

measurements, taken 1 year apart, were performed

in this study due to concerns regarding practicality

and the burden on participating families. Therefore,

caution should be exercised in generalising the

results with respect to longitudinal trends, given

that substantial intra-individual fluctuations may

have occurred but were not captured in this study.

Second, both parental stress and child health

were assessed using parent-report questionnaires,

which may contribute to increased shared method

variance. Additionally, aspects of the child’s health

or behaviour considered problematic by the parent may not align with assessments made by other

individuals (eg, teachers). As mentioned earlier,

parents with depression may be biased towards

over-reporting problems and are more likely to

report behavioural issues in their child compared

with other informants.47 48 The validity of parent-perceived

measures of child health—particularly

in relation to parental depression—and their

agreement with other caregivers should be examined

in future trials specifically designed for this purpose.

Third, there were unmeasured confounders in this

observational study, such as exercise and social

functioning. Moreover, certain socio-demographic

factors, including marital and employment statuses,

were assumed to be static throughout the study. It

remains uncertain whether changes in these factors,

if any, may have influenced the observed results.

Additional information regarding participant

characteristics, observational measures of child

behaviour, or objective indicators of child health (eg,

cortisol levels) could improve the reliability of the

findings.

Conclusion

This study showed that a substantial proportion of

parents from low-income families in Hong Kong

experienced general stress due to multiple stressors,

which was negatively associated with their child’s

health. A bidirectional relationship was observed

between parental stress and child health over time,

which may be partly mediated by parental depression.

Prompt screening and appropriate intervention are

necessary to prevent adverse health outcomes for

parents and children in low-income families.

Author contributions

Concept or design: EYT Yu, RSM Wong, AFY Tiwari, CKH Wong, VY Guo, CLK Lam.

Acquisition of data: RSM Wong, KSN Liu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: EYT Yu, EYF Wan, RSM Wong, IL Mak, AFY Tiwari, CKH Wong, VY Guo, CLK Lam.

Drafting of the manuscript: EYT Yu, RSM Wong, IL Mak, CHN Yeung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: RSM Wong, KSN Liu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: EYT Yu, EYF Wan, RSM Wong, IL Mak, AFY Tiwari, CKH Wong, VY Guo, CLK Lam.

Drafting of the manuscript: EYT Yu, RSM Wong, IL Mak, CHN Yeung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As advisors of the journal, EYT Yu and CKH Wong were

not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have

disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful for the support from Kerry Group

Kuok Foundation (Hong Kong) Limited in conducting this

study on participants of the Trekkers Family Enhancement

Scheme. The authors’ sincere gratitude goes to the

Neighbourhood Advice-Action Council, Hong Kong Sheng

Kung Hui Lady MacLehose Centre, and Shek Lei Community

Hall for their assistance in participant recruitment and

provision of venues for data collection, respectively. The

authors thank the Social Science Research Centre of The

University of Hong Kong (HKU) for their timely completion

of the telephone surveys, and Department of Paediatrics

and Adolescent Medicine of HKU for performing the assays

for DNA extraction and telomere length measurement. The

authors also thank the hard work of their research staff in data

collection and analysis.

Declaration

The study results were disseminated through a poster

presentation at the Health Research Symposium 2021 (23

November 2021, hybrid conference), entitled “In-depth

exploration of a bidirectional parent-child health relationship

and its mediating and moderating factors among low-income

families in Hong Kong”.

Funding/support

This research was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund of the Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR

Government (Ref No.: HMRF 14151571). The funder

had no role in the study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority

Hong Kong West Cluster, Hong Kong (Ref No.: UW 16-415).

Informed consent was obtained from patients when baseline

data were collected.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Santiago CD, Kaltman S, Miranda J. Poverty and mental

health: how do low-income adults and children fare in

psychotherapy? J Clin Psychol 2013;69:115-26. Crossref

2. Smith MV, Mazure CM. Mental health and wealth:

depression, gender, poverty, and parenting. Annu Rev Clin

Psychol 2021;17:181-205. Crossref

3. Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation,

and coping. Child Dev Perspect 2013;7:43-8. Crossref

4. Adjei NK, Jonsson KR, Straatmann VS, et al. Impact of

poverty and adversity on perceived family support in

adolescence: findings from the UK Millennium Cohort

Study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024;33:3123-32. Crossref

5. Alto ME, Warmingham JM, Handley ED, Manly JT,

Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The association between patterns of

trauma exposure, family dysfunction, and psychopathology

among adolescent females with depressive symptoms from

low-income contexts. Child Maltreat 2023;28:130-40. Crossref

6. van Dijk W, de Moor MH, Oosterman M, Huizink AC,

Matvienko-Sikar K. Longitudinal relations between

parenting stress and child internalizing and externalizing

behaviors: testing within-person changes, bidirectionality

and mediating mechanisms. Front Behav Neurosci

2022;16:942363. Crossref

7. Neece CL, Green SA, Baker BL. Parenting stress and child

behavior problems: a transactional relationship across

time. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil 2012;117:48-66. Crossref

8. Stone LL, Mares SH, Otten R, Engels RC, Janssens JM.

The co-development of parenting stress and childhood

internalizing and externalizing problems. J Psychopathol

Behav Assess 2016;38:76-86. Crossref

9. Economic Analysis Division Economic Analysis

and Business Facilitation Unit Financial Secretary’s

Office; Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Hong Kong Poverty Situation

Report 2013. Oct 2014. Available from: https://www.commissiononpoverty.gov.hk/eng/pdf/poverty_report13_rev2.pdf. Accessed 31 Jul 2023.

10. Lam CL, Guo VY, Wong CK, Yu EY, Fung CS. Poverty and

health-related quality of life of people living in Hong Kong:

comparison of individuals from low-income families and

the general population. J Public Health (Oxf) 2017;39:258-65.Crossref

11. Luecken LJ, Lemery KS. Early caregiving and physiological

stress responses. Clin Psychol Rev 2004;24:171-91. Crossref

12. Hanington L, Ramchandani P, Stein A. Parental depression

and child temperament: assessing child to parent effects

in a longitudinal population study. Infant Behav Dev

2010;33:88-95. Crossref

13. Associations between depression in parents and parenting,

child health, and child psychological functioning. In:

England MJ, Sim LJ, editors. Depression in Parents,

Parenting, and Children: Opportunities to Improve

Identification, Treatment, and Prevention. Washington

(DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009: 119-82.

14. Lee SL, Cheung YF, Wong HS, Leung TH, Lam T, Lau YL.

Chronic health problems and health-related quality of life

in Chinese children and adolescents: a population-based

study in Hong Kong. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001183. Crossref

15. Chan KL, Lo CK, Ho FK, Chen Q, Chen M, Ip P. Modifiable

factors for the trajectory of health-related quality of life

among youth growing up in poverty: a prospective cohort

study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:9221. Crossref

16. Asok A, Bernard K, Roth TL, Rosen JB, Dozier M. Parental responsiveness moderates the association between early-life stress and reduced telomere length. Dev Psychopathol

2013;25:577-85. Crossref

17. Evans GW, Kim P, Ting AH, Tesher HB, Shannis D.

Cumulative risk, maternal responsiveness, and allostatic

load among young adolescents. Dev Psychol 2007;43:341-51. Crossref

18. Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol

2005;1:293-319. Crossref

19. Power C, Weise V, Mack JT, Karl M, Garthus-Niegel S.

Does parental mental health mediate the association

between parents’ perceived stress and parent-infant

bonding during the early COVID-19 pandemic? Early

Hum Dev 2024;189:105931. Crossref

20. Fung CS, Yu EY, Guo VY, et al. Development of a Health

Empowerment Programme to improve the health of

working poor families: protocol for a prospective cohort

study in Hong Kong. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010015. Crossref

21. Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF; Psychology Foundation of

Australia. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales.

Sydney: Sydney Psychology Foundation; 1995. Crossref

22. Wang K, Shi HS, Geng FL, et al. Cross-cultural validation of

the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale–21 in China. Psychol

Assess 2016;28:e88-100. Crossref

23. Landgraf JM. Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ). In:

Maggino F, editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and

Well-being Research. Cham: Springer; 2020: 1-6. Crossref

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity

of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med

2001;16:606-13. Crossref

25. Kavikondala S, Stewart SM, Ni MY, et al. Structure and

validity of Family Harmony Scale: an instrument for

measuring harmony. Psychol Assess 2016;28:307-18. Crossref

26. Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence:

the Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. J Marriage Fam

1979;41:75-88. Crossref

27. Chan KL, Brownridge DA, Fong DY, Tiwari A, Leung WC,

Ho PC. Violence against pregnant women can increase the

risk of child abuse: a longitudinal study. Child Abuse Negl

2012;36:275-84. Crossref

28. Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. The

Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ).

In: Perlmutter BF, Touliatos J, Holden GW, editors.

Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques: Vol 3.

Instruments & Index. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2001: 319-21.

29. Wu P, Robinson CC, Yang C, et al. Similarities and

differences in mothers’ parenting of preschoolers in China

and the United States. Int J Behav Dev 2002;26:481-91. Crossref

30. Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods

and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy.

Science 1997;277:918-24. Crossref

31. Chou KL. Perceived discrimination and depression among

new migrants to Hong Kong: the moderating role of social

support and neighborhood collective efficacy. J Affect

Disord 2012;138:63-70. Crossref

32. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable

distinction in social psychological research: conceptual,

strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol

1986;51:1173-82. Crossref

33. Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation

modeling. J Stat Softw 2012;48:1-36. Crossref

34. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Hong Kong 2016 Population By-census–Thematic Report: Household Income Distribution in Hong Kong. Jun 2017. Available from: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1120096/att/B11200962016XXXXB0100.pdf . Accessed 25 Aug 2025.

35. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. 2021 Population Census—Thematic

Report: Children. Feb 2023. Available from: https://www.census2021.gov.hk/doc/pub/21c-Children.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2025.

36. Chan KL. Intimate partner violence in Hong Kong. In:

Chan KL, editor. Preventing Family Violence: A

Multidisciplinary Approach. Hong Kong: Hong Kong

University Press; 2012: 19-58. Crossref

37. Non-Communicable Disease Branch, Centre for Health

Protection, Hong Kong SAR Government. Report of

Population Health Survey 2020-22 (Part I); 2022. Available

from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_1_report_eng_rectified.pdf. Accessed 31 Jul 2023.

38. Chan SM, Wong H, Chung RY, Au-Yeung TC. Association

of living density with anxiety and stress: a cross-sectional

population study in Hong Kong. Health Soc Care

Community 2021;29:1019-29. Crossref

39. Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C,

Low C. Pre-school children with and without developmental

delay: behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. J

Intellect Disabil Res 2003;47:217-30. Crossref

40. Motrico E, Bina R, Kassianos AP, et al. Effectiveness of

interventions to prevent perinatal depression: an umbrella

review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp

Psychiatry 2023;82:47-61. Crossref

41. Vameghi R, Amir Ali Akbari S, Sajedi F, Sajjadi H, Alavi

Majd H. Path analysis association between domestic

violence, anxiety, depression and perceived stress in

mothers and children’s development. Iran J Child Neurol

2016;10:36-48. Crossref

42. Xu L, Xu J. The impact of maternal occupation on

children’s health: a mediation analysis using the parametric

G-formula. Soc Sci Med 2024;343:116602. Crossref

43. Bellón JÁ, Conejo-Cerón S, Sánchez-Calderón A, et al.

Effectiveness of exercise-based interventions in reducing

depressive symptoms in people without clinical depression:

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised

controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry 2021;219:578-87. Crossref

44. Newland P, Bettencourt BA. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based

art therapy for symptoms of anxiety, depression,

and fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Complement Ther Clin Pract 2020;41:101246. Crossref

45. Marx W, Manger SH, Blencowe M, et al. Clinical guidelines

for the use of lifestyle-based mental health care in major

depressive disorder: World Federation of Societies for

Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Australasian Society

of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) taskforce. World J Biol

Psychiatry 2023;24:333-86. Crossref

46. Recchia F, Leung CK, Chin EC, et al. Comparative

effectiveness of exercise, antidepressants and their

combination in treating non-severe depression: a systematic

review and network meta-analysis of randomised

controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 2022;56:1375-80. Crossref

47. Chi TC, Hinshaw SP. Mother–child relationships of

children with ADHD: the role of maternal depressive

symptoms and depression-related distortions. J Abnor

Child Psychol 2002;30:387-400. Crossref

48. Richters JE. Depressed mothers as informants about their

children: a critical review of the evidence for distortion.

Psychol Bull 1992;112:485-99. Crossref