Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 12 Jun 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Living donor renal transplantation in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus: a case report

TL Leung, MB ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Jacky MC Chan, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP2; Ivy LY Wong, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP1; Clara KY Poon, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP1; William Lee, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP1; KF Yim, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP1; Owen TY Tsang, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP2; Samuel KS Fung, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP1; A Cheuk, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP1; HL Tang, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP1

1 Renal Unit, Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Infectious Disease Unit, Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr TL Leung (ltl125@ha.org.hk)

Case presentation

The patient was diagnosed in 1989, at age 27 years,

with human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)

infection. He later presented with hypertension and

left loin discomfort. Workup revealed proteinuria of

0.51 g over 24 hours and impaired renal function,

with serum creatinine of 230 μmol/L (normal range,

59-104 μmol/L). An ultrasound scan showed bilateral

shrunken kidneys with loss of corticomedullary

differentiation. Renal biopsy was not performed

in view of the bilateral shrunken kidneys. His

renal function progressively deteriorated, and he

commenced automated peritoneal dialysis in June

2017 at age 55 years. His elder brother volunteered

to donate a kidney. The patient’s HIV infection was

well controlled with lamivudine, abacavir, lopinavir,

and ritonavir. Lopinavir/ritonavir was switched to

raltegravir in view of a potential drug-drug interaction

between ritonavir and calcineurin inhibitors. Pre-transplantation

CD4+ count was 717 cells/μL and

HIV viral load was undetectable. Human leukocyte

antigen matching revealed one mismatch between

donor and recipient. Both donor and recipient tested

cytomegalovirus antibody positive. The recipient

was started on cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil,

and prednisolone for immunosuppression according

to our centre’s protocol.

Living donor renal transplantation was

successfully performed in September 2018

when the patient was 56 years old. Postoperative

ultrasound of the graft kidney and radioisotope

scan showed good graft perfusion and function.

Valganciclovir and pentamidine inhalation were

given as prophylaxis against cytomegalovirus and

Pneumocystis jirovecii, respectively, in view of his

underlying glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency. The

lowest creatinine level since hospital discharge was

112 μmol/L. At 6 months post-transplantation,

he was found to have a low level of donor-specific

anti-DQ7 antibody (DSA), which persisted at repeat

testing 9 months post-transplantation. Cyclosporine was therefore switched to tacrolimus to optimise

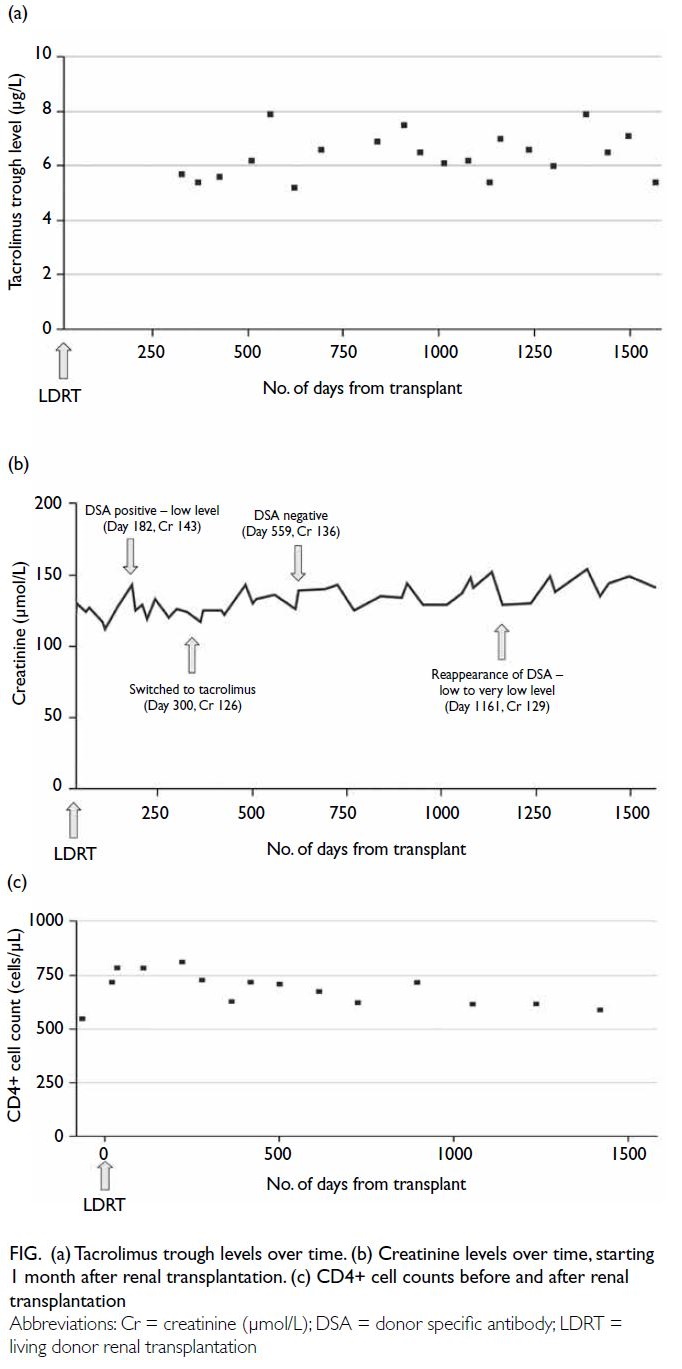

immunosuppression. The tacrolimus trough level has

been maintained at 5 to 8 μg/L since commencement

(Fig a). Despite the presence of DSA, the patient has

enjoyed stable renal function with no proteinuria;

thus, renal biopsy was not performed (Fig b). In his

latest follow-up, at 51 months post-transplantation,

his renal function remained stable with a creatinine

level of 141 μmol/L. He also has excellent HIV control

with abacavir, dolutegravir, and lamivudine. CD4+

cell count has been maintained in the range of 600 to

800 cells/μL since transplantation (Fig c). He did not

experience any infections after transplantation.

Figure. (a) Tacrolimus trough levels over time. (b) Creatinine levels over time, starting 1 month after renal transplantation. (c) CD4+ cell counts before and after renal transplantation

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported

case of living donor renal transplantation in a patient

with HIV in Hong Kong. The global prevalence of

HIV is increasing, and its association with chronic

kidney disease is notable. In a local cohort, 16.8%

of Chinese HIV-infected patients developed

chronic kidney disease.1 With the advancement

of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART),

life expectancy among people living with HIV

(PLHIV) approaches that of the general population,

leading to more cases of end-stage renal failure

requiring management. The combination of intense

immunosuppression and intrinsic immunodeficiency

can expose HIV-infected transplant recipients

to life-threatening opportunistic infections. It is

crucial to achieve excellent HIV control before

proceeding with transplantation. The American

Society of Transplantation recommends that PLHIV

achieve a CD4+ cell count of more than 200 cells/μL during the 3 months prior to transplantation

and an undetectable HIV viral load while receiving

HAART.2 Our patient met these criteria prior to

transplantation.

Kidney transplantation in PLHIV has been

explored in many Western countries over the past decades. In a systematic review, the 1- and 3-year

patient survival rates after transplantation were

reported at 97% and 94%, respectively, with graft

survival at 91% and 81%.3 In another cohort study that compared 510 HIV-infected kidney transplant

recipients with HIV-negative controls, comparable

5- and 10-year survival rates were reported; 5-year

patient and graft survival were 88.7% and 75%,

respectively. Co-infection of HIV and hepatitis C

virus was an important prognostic marker for poor

graft and patient survival.4 These excellent survival

data encouraged us to perform the first kidney

transplant in an HIV-infected patient. Despite these

promising results, the rejection rate in HIV-infected

recipients is significantly higher, up to 2- to 3-fold,

potentially due to drug-drug interactions between

HAART and immunosuppressants or immune

dysregulation.5 6 The pathophysiology behind this

increased rejection rate is unclear, but strategies

such as induction therapy with anti-interleukin-2

receptor antibody or antithymocyte globulin and

optimised immunosuppressive therapy are utilised to

mitigate risks. Nonetheless, the use of antithymocyte

globulin is controversial due to its association with

marked CD4+ cell suppression (ie, <200 cells/μL),

prolonged recovery, and subsequent infection risk.7

Therefore, antithymocyte globulin induction should

be reserved for HIV-infected recipients with very

high immunological risk.

The optimal immunosuppression regimen for

HIV-infected recipients is yet to be determined.

Tacrolimus is favoured over cyclosporine for

reducing acute rejection risks.8 Observational studies

and the landmark ELITE-Symphony trial suggest

lower rejection rates with tacrolimus, up to 2-fold.6 8 Our centre initially chose cyclosporine due

to the patient’s low immunological risk profile with

only one human leukocyte antigen mismatch but

switched to tacrolimus after the development of DSA

6 months post-transplantation. This case highlights

the challenges of balancing overimmunosuppression

and rejection risks in HIV-infected recipients.

Ongoing evidence supports the use of tacrolimus as

the first-line immunosuppressive agent, irrespective

of immunological risk, with future randomised

controlled trials needed to establish the best regimen.

Managing drug-drug interactions in HIV-infected

transplant recipients is complex. Non-nucleoside

reverse transcriptase inhibitors induce

cytochrome P450 enzymes, while protease inhibitors

significantly inhibit these enzymes, notably raising

calcineurin inhibitor levels in the plasma. Ritonavir,

a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor commonly used in

HAART, requires a substantial increase in tacrolimus

dosage up to 70-fold upon its discontinuation to

maintain effective immunosuppression.9 To avoid

drug-drug interactions, our patient was switched to

an integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based HAART

regimen prior to transplantation. Nonetheless, there

was a risk of serum creatinine elevation. Dolutegravir

has been shown to inhibit organic cation transporter

2, which inhibits active creatinine secretion into renal tubules, leading to a slight elevation in serum

creatinine level without affecting the glomerular

filtration rate. After administering dolutegravir,

serum creatinine clearance in healthy subjects has

been reported to decrease by 10% to 14%.10

In conclusion, renal transplantation in PLHIV

can offer improved quality of life and survival

compared with continued dialysis, provided there

is excellent HIV control and careful management

of immunosuppression and drug-drug interactions.

Challenges remain in preventing and treating acute

rejection to improve long-term graft survival. We

observed an early appearance of DSA 6 months post-transplantation

in our patient. Although the DSA was

transiently suppressed after switching to tacrolimus,

it reappeared later. The appearance of DSA and its

potential long-term impact on graft survival require

further investigation. Our experience, alongside data

from Western cohorts, supports expanding renal

transplantation among HIV-infected patients, with a

focus on tailored immunosuppressive strategies and

management of complications.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study,

acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

This case has been presented during oral presentation at

the 18th Congress of The Asian Society of Transplantation

(CAST) in Hong Kong SAR, China, 25-28 July 2023.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and provided informed consent for all procedures.

References

1. Cheung CY, Wong KM, Lee MP et al. Prevalence of chronic

kidney disease in Chinese HIV-infected patients. Nephrol

Dial Transplant 2007;22:3186-90. Crossref

2. Blumberg EA, Rogers CC; American Society of

Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of

Practice. Solid organ transplantation in the HIV-infected

patients: Guidelines from the American Society of

Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of

Practice. Cli Transplant 2019;33:e13499. Crossref

3. Zheng X, Gong L, Xue W, et al. Kidney transplant outcomes

in HIV-positive patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

AIDS Res Ther 2019;16:37. Crossref

4. Locke JE, Mehta S, Reed RD, et al. A national study

of outcomes among HIV-infected kidney transplant

recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26:2222-9. Crossref

5. Stock PG, Barin B, Murphy B, et al. Outcomes of kidney

transplantation in HIV-infected recipients. N Engl J Med

2010;363:2004-14. Crossref

6. Gathogo E, Harber M, Bhagani S, et al. Impact of tacrolimus

compared with cyclosporin on the incidence of acute

allograft rejection in Human Immunodeficiency virus-positive

kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation

2016;100:871-8. Crossref

7. Carter JT, Melcher ML, Carlson LL, Roland ME, Stock PG.

Thymoglobulin-associated Cd4+ T-cell depletion and

infection risk in HIV-infected renal transplant recipients.

Am J Transplant 2006;6:753-60. Crossref

8. Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, et al. Reduced

exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation.

N Engl J Med 2007;357:2562-75. Crossref

9. Jimenez HR, Natali KM, Zahran AA. Drug interaction after

ritonavir discontinuation: considerations for antiretroviral

therapy changes in renal transplant recipients. Int J STD

AIDS 2019;30:710-4. Crossref

10. Koteff J, Borland J, Chen S, et al. A phase 1 study to evaluate

the effect of dolutegravir on renal function via measurement

of iohexol and para-aminohippurate clearance in healthy

subjects. Br J Cli Pharmacol 2013;75:990-6. Crossref