Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 5 Dec 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Specific indicators of unsuitability for

transarterial chemoembolisation in patients with

intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma

according to thresholds of tumour burden and

liver function as judged by survival benefit over

sorafenib

LM Chen, PhD1,2,3; Simon CH Yu, MB, BS, MD1; Leung Li, MB, ChB, MD4; Edwin P Hui, MB, ChB, MD4; Winnie Yeo, MB, BS, MD4,5; Stephen L Chan, MB, BS, MD4,5

1 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Faculty of

Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Medical Ultrasonics, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun

Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

3 Biomedical Innovation Center, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen

University, Guangzhou, China

4 Department of Clinical Oncology, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 State Key Laboratory of Translational Oncology, China

Corresponding author: Dr Simon CH Yu (simonyu@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to define specific

indicators of unsuitability for transarterial

chemoembolisation (TACE) in patients with

intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

in Hong Kong using thresholds of tumour burden

and liver function, as judged by survival benefit over

sorafenib.

Methods: Patients with treatment-naïve and

unresectable HCC who received TACE or sorafenib

from 2005 to 2019 and met the eligibility criteria

were enrolled. Overall survival (OS) was compared

between the TACE and sorafenib groups using

the log-rank test and hazard ratios (HRs) in all

subgroups classified according to baseline modified

albumin–bilirubin (mALBI) grade and tumour

burden, including the up-to-7, up-to-11, and N3-S5-S10 criteria.

Results: Overall survival was significantly longer in

TACE subgroups than in sorafenib subgroups when

stratified by mALBI grade and either the up-to-7 or

the up-to-11 criteria (all P<0.05). When applying

the N3-S5-S10 criteria, OS did not significantly

differ between the TACE and sorafenib groups in

subgroups with mALBI grade 2b and tumours with

number >3 and size >5 cm but ≤10 cm, or tumours

with number >3 and size >10 cm (HR=0.550 and

0.965, respectively; both P>0.05). Sensitivity analysis

showed non-significant survival benefits in two

additional subgroups: those with mALBI grade 2b and tumours with number ≤3 and size >10 cm, and

those with mALBI grade 1 or 2a and tumours with

number >3 and size >10 cm (HR=0.474 and 0.418,

respectively; both P>0.05).

Conclusion: More precise criteria for TACE

unsuitability are required. The combination of

mALBI grade and the N3-S5-S10 criteria may better

identify patients with intermediate-stage HCC who

are unlikely to benefit from TACE. Validation in a

larger cohort is warranted.

New knowledge added by this study

- Patients regarded as unsuitable for transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) under existing criteria may achieve better survival outcomes with TACE than those with systemic therapy.

- To determine true TACE unsuitability, more precise criteria based on clinical evidence demonstrating improved survival with alternative treatments are required. Modified albumin–bilirubin (mALBI) grade 2b and tumours with number >3 and size >5 cm, or tumours with number ≤3 and size >10 cm, as well as mALBI grade 1 or 2a and tumours with number >3 and size >10 cm, could serve as better indicators of TACE unsuitability in patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Within the framework of TACE unsuitability, the use of more precise discriminatory criteria is crucial to ensure that patients are not inappropriately excluded from the potential benefits of TACE.

- The integration of mALBI grade with the N3-S5-S10 tumour burden criteria may offer a practical framework for clinicians to individualise treatment selection, optimising outcomes by identifying patients more likely to benefit from TACE versus systemic therapy.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading

malignancies worldwide. At diagnosis, up to 30% of

patients have intermediate-stage HCC according

to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer system.1

Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) has

emerged as the first-line treatment for intermediate-stage

HCC, supported by two randomised controlled

trials2 3 and a meta-analysis4 that demonstrated

superior survival outcomes compared with best

supportive care or suboptimal therapies.

Because patients with intermediate-stage HCC

comprise a heterogeneous group characterised by

a wide range of tumour burdens and liver function,

the effectiveness of TACE as first-line treatment may

not be universal, particularly in subgroups with high

tumour burden or suboptimal liver function. To

address this issue, sub-staging of intermediate-stage

HCC based on tumour burden and liver function

has been proposed in several criteria, including

the Bolondi,5 Kinki,6 and MICAN (Modified

Intermediate Stage of Liver Cancer) criteria.7

These criteria have demonstrated discriminative prognostic value in identifying subgroups of patients

with intermediate-stage HCC.7 8 Given that survival

outcomes of patients treated with TACE can vary

across substages of intermediate-stage HCC, it is

clinically essential to identify thresholds of tumour

burden and liver function that preclude the use of

TACE according to survival benefit.

Sorafenib has been established as the standard

of care for advanced HCC since 2007, based on the

demonstration of its significant survival superiority

over placebo.9 10 11 Subgroup analyses of clinical

trials have shown that sorafenib exerts positive

therapeutic efficacy in intermediate-stage HCC, with

reported overall survival (OS) ranging from 14.5 to

20.6 months,9 12 13 which is comparable to the OS

achieved with TACE. Sorafenib treatment can serve

as a benchmark for evaluating the survival benefit

of TACE. If TACE does not provide a significant

survival benefit compared with sorafenib, it may not

be appropriate to subject patients to TACE rather

than systemic therapy, given that TACE is invasive

and potentially harmful to the liver. Patients may

benefit from systemic therapy before liver function

becomes suboptimal.

It has been hypothesised that specific baseline

parameters of tumour burden and liver function, at

which TACE fails to show superior survival benefit

compared with sorafenib, could be defined as

indicators of TACE unsuitability. This study aimed

to define specific indicators of TACE unsuitability

at baseline in patients with intermediate-stage HCC

according to thresholds of tumour burden and liver

function, as judged by the survival benefit of TACE

over sorafenib.

Methods

Study design

Due to the limited number of eligible participants,

all available cases with complete clinical data were

included. All patients with unresectable HCC who

received TACE or sorafenib therapy from January

2005 to December 2019 at Prince of Wales Hospital

were enrolled in the study, provided they met all

eligibility criteria. Unresectability of intermediate-stage

HCC was determined by a multidisciplinary

team comprising a surgeon, an interventional

radiologist, and an oncologist. Inclusion criteria were

treatment-naïve, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-B

stage HCC diagnosed by biopsy or a typical vascular

pattern on cross-sectional imaging; intrahepatic

disease without vascular invasion; and an Eastern

Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

score of 0 or 1. Exclusion criteria included age

under 18 years or Eastern Cooperative Oncology

Group performance status score of 2 or above;

prior treatment before initial TACE; receipt of

hepatectomy, liver transplantation, or local therapy after initial TACE; and any imaging evidence from

computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance

imaging, or positron emission tomography/CT

showing vascular invasion by tumour (including

portal vein tumour thrombus) or extrahepatic

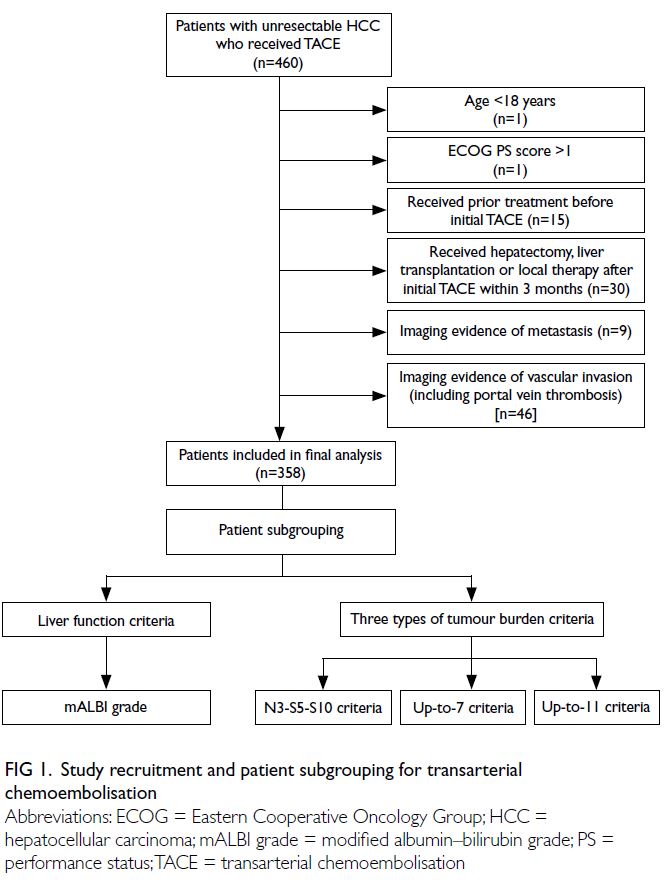

metastasis (Fig 1). To identify thresholds for TACE

unsuitability, OS of patients treated with TACE was

compared with that of patients treated with sorafenib

within subgroups defined by baseline tumour burden

and liver function. Overall survival was defined as the

interval between the initiation of TACE or sorafenib

and death from any cause. Patients who were alive or

lost to follow-up were censored.

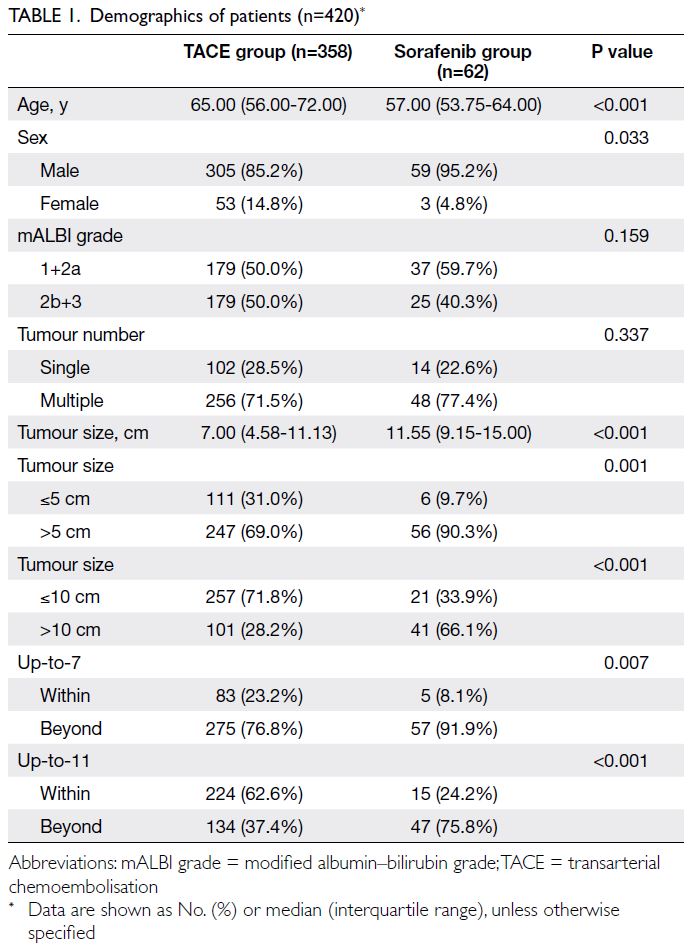

Study participants

In total, 420 patients were enrolled in the study: 358

received TACE and 62 received sorafenib (Table 1).

The TACE group included significantly more older

and female patients. The median tumour size was

significantly larger in the sorafenib group compared

with the TACE group. No significant differences

were observed between the two groups in terms

of the modified albumin–bilirubin (mALBI) grade

distribution or tumour multiplicity. Among patients

initially treated with TACE, the median number of

TACE sessions was two (range, 1-4); 124 patients

received one session, 78 received two sessions, 53

received three sessions, and 103 received more than

three sessions. After developing refractoriness to

TACE, 60 patients subsequently received systemic

agents; of these, 35 received sorafenib, eight received

adriamycin, four received doxorubicin, six received

lenvatinib, and seven received other agents.

Patient subgrouping

Patients were classified into six subgroups according

to baseline tumour burden and liver function.

Tumour burden was subcategorised using the up-to-7, up-to-11, and N3-S5-S10 criteria. The up-to-7

and up-to-11 criteria were derived from the sum of

the maximum tumour size (in cm) and the tumour

number, with cut-off values of 7 or 11, respectively.

Accordingly, patients were categorised as within or

beyond the up-to-7 and up-to-11 criteria. In the N3-S5-S10 system, tumour burden was subcategorised

according to the combination of tumour number and

maximum tumour size; three tumour nodules and

5 cm or 10 cm in size served as the respective cut-off

values. This categorisation resulted in the following

six subgroups: (1) tumour number ≤3, tumour size

≤5 cm; (2) tumour number ≤3, tumour size >5 cm

to ≤10 cm; (3) tumour number ≤3, tumour size >10

cm; (4) tumour number >3, tumour size ≤5 cm; (5)

tumour number >3, tumour size >5 cm to ≤10 cm; and

(6) tumour number >3, tumour size >10 cm (Fig 1).

Liver function subgroups were classified

according to the mALBI grade.14 The mALBI grades

were determined using the ALBI score, calculated as (log10 [bilirubin level (μmol/L)] × 0.66) + (albumin

level [g/L] × –0.085). Based on three cut-off ALBI

scores, grades were defined as follows: grade 1

(≤–2.60), grade 2a (>–2.60 to ≤–2.27), grade 2b

(>–2.27 to ≤–1.39), and grade 3 (>–1.39). Because

the sample size of patients receiving sorafenib with

mALBI grade 1 or 2a was relatively small, these two

subgroups were combined for analysis. Additionally,

given that no patient with mALBI grade 3 received

sorafenib, this subgroup was excluded from the

analysis (Fig 1).

Transarterial chemoembolisation

The TACE procedures were performed using

digital subtraction angiography equipment via

a femoral approach under local anaesthesia.15 16

In brief, a microcatheter was used to catheterise

tumour-feeding arteries at the lobar, segmental,

or subsegmental level, depending on tumour size.

An emulsion of cisplatin–ethiodised oil (Platosin;

Pharmachemie BV, Haarlem, the Netherlands),

consisting of up to 20 mg aqueous cisplatin (20 mL) and up to 20-mL ethiodised oil mixed in a 1:1 volume

ratio, was administered until flow stasis occurred or

a maximum dose of 40-mL emulsion was delivered.

Digital subtraction angiography, with or without

non-contrast multiplanar CT, was used to confirm

treatment completeness. A gelatin sponge (5-10 mL)

was used to embolise the feeding arteries.

Postprocedure monitoring included blood

tests for liver function and tumour markers within

2 days, at 2 weeks, and then every 1 to 3 months, as

well as CT imaging every 3 months. Systemic therapy

was administered to patients with well-preserved

liver function who developed TACE refractoriness,

as indicated by continuous elevation of tumour

markers and CT evidence of tumour progression.

Systemic therapy

According to the customary protocol at Prince

of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of

Hong Kong during the study period, patients with

unresectable intermediate-stage HCC and no contraindications to TACE were prioritised for

TACE treatment. Patients who declined TACE were

treated with sorafenib; as a result, some patients in

the sorafenib group had smaller tumours or fewer

tumour nodules. Sorafenib was administered orally

at a prescribed dose of 400 mg twice daily. In the

event of intolerable side-effects or serious adverse

events, oncologists could adjust the treatment by

reducing the dose or discontinuing the drug.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as numbers

(percentages), while continuous variables were

summarised as median (interquartile range), median

(95% confidence interval [95% CI]), or depending

on the results of normality testing. The Chi squared

test was used to compare categorical data, and the

Mann-Whitney U test was performed for continuous

data. Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional

hazards models were used to compare OS values

among subgroups. The log-rank test and hazard

ratio (HR) were utilised to assess survival differences

between subgroups. A sensitivity analysis of survival

outcomes was conducted, excluding participants

who received systemic therapy after TACE. A P

value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

(Windows version 25.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

United States).

Results

Comparison of overall survival between

transarterial chemoembolisation and sorafenib

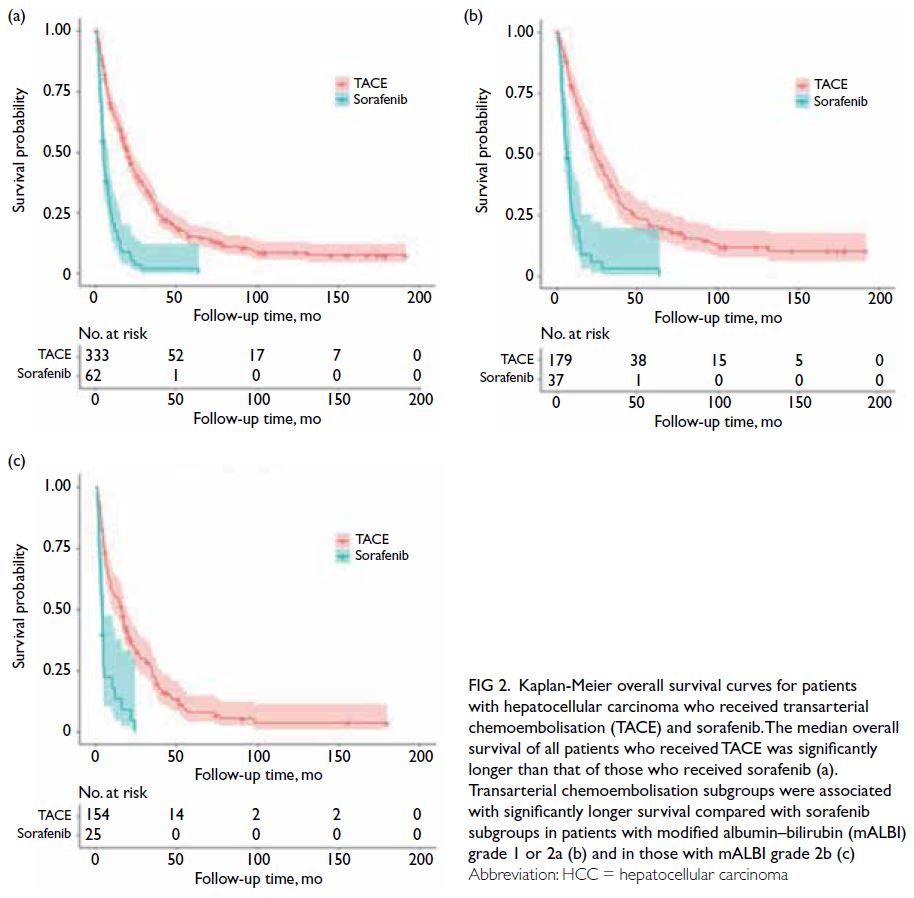

The median OS of all patients who received TACE

was significantly longer than that of patients who

received sorafenib (19.37 [16.89-21.85] months vs

5.12 [4.37-5.84] months, P<0.001; Fig 2a). When

stratified by mALBI grade, patients with mALBI

grade 1 or 2a had significantly longer median OS in

the TACE group compared with the sorafenib group

(23.83 [18.53-29.13] months vs 6.60 [3.61-9.59]

months, P<0.001; Fig 2b). Similarly, patients with

mALBI grade 2b had significantly longer median

OS in the TACE group than in the sorafenib group

(16.20 [11.91-20.49] months vs 4.39 [3.44-5.35]

months, P<0.001; Fig 2c).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who received transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) and sorafenib. The median overall survival of all patients who received TACE was significantly longer than that of those who received sorafenib (a). Transarterial chemoembolisation subgroups were associated with significantly longer survival compared with sorafenib subgroups in patients with modified albumin–bilirubin (mALBI) grade 1 or 2a (b) and in those with mALBI grade 2b (c)

Overall survival by modified albumin–bilirubin grade and tumour burden in

sorafenib-treated patients

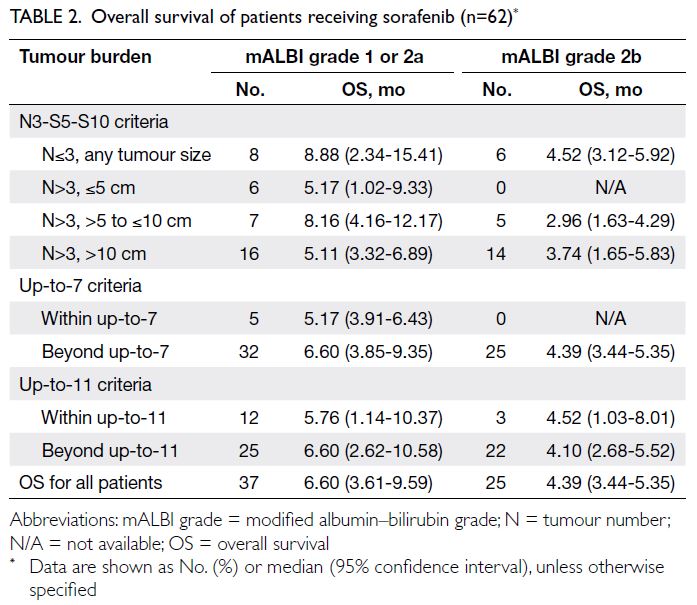

The median OS of patients treated with sorafenib,

stratified by mALBI grade and tumour burden, is

summarised in Table 2. As the sorafenib subgroups

with tumour number ≤3 had a relatively small

sample size (n=8) according to the N3-S5-S10

criteria, these patients were not further subdivided based on tumour size. Instead, they were combined

into a single subgroup with tumour number ≤3 to

increase the sample size for comparison with the

TACE group. Consequently, OS in the combined

sorafenib subgroup (tumour number ≤3, any tumour

size) was used for comparison with OS in the three

tumour-size TACE subgroups of tumour number ≤3

(Table 2).

The distribution of sample sizes was uneven

across the sorafenib subgroups with tumour number

>3 based on the N3-S5-S10 criteria, which may have

introduced bias in the survival outcomes, such as a

lower tumour burden being associated with worse

OS. To avoid underestimation of OS in any tumour-size

subgroup when comparing with the TACE

subgroups, the longest OS among the subgroups

with tumour number >3 was utilised as the OS value

for all these subgroups in the analysis, irrespective of tumour size (Table 2). As no patients with mALBI

grade 2 were present in the tumour burden subgroup

defined as within up-to-7, the OS of patients with

tumour burden beyond up-to-7 (Table 2) who were

treated with sorafenib was used as the control.

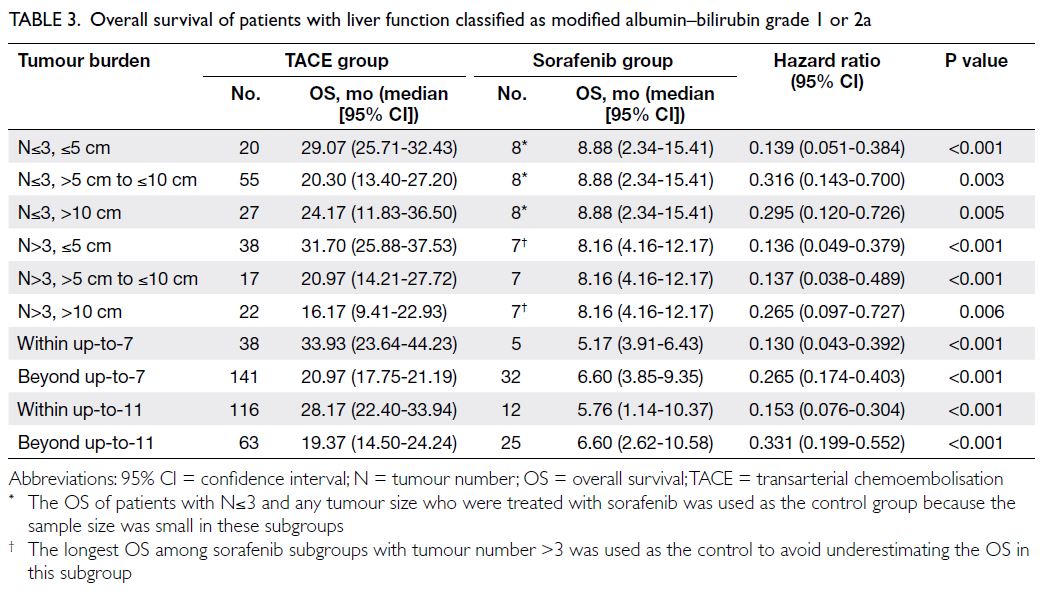

Overall survival in modified albumin–bilirubin grade 1 or 2a: transarterial chemoembolisation versus sorafenib

Table 3 presents the median OS of patients treated

with TACE or sorafenib, stratified by mALBI grade

1 or 2a and tumour burden. Across all subgroups

defined by various tumour burden criteria, patients

who received TACE achieved significantly longer

OS than those who received sorafenib (all P<0.05),

with HRs favouring TACE (ranging from 0.130 to

0.331). Sensitivity analysis showed that survival

was not significantly different between TACE and sorafenib in the subgroup with tumour number >3

and tumour size >10 cm (HR=0.418 [95% CI=0.147-1.171]; P=0.097).

Table 3. Overall survival of patients with liver function classified as modified albumin–bilirubin grade 1 or 2a

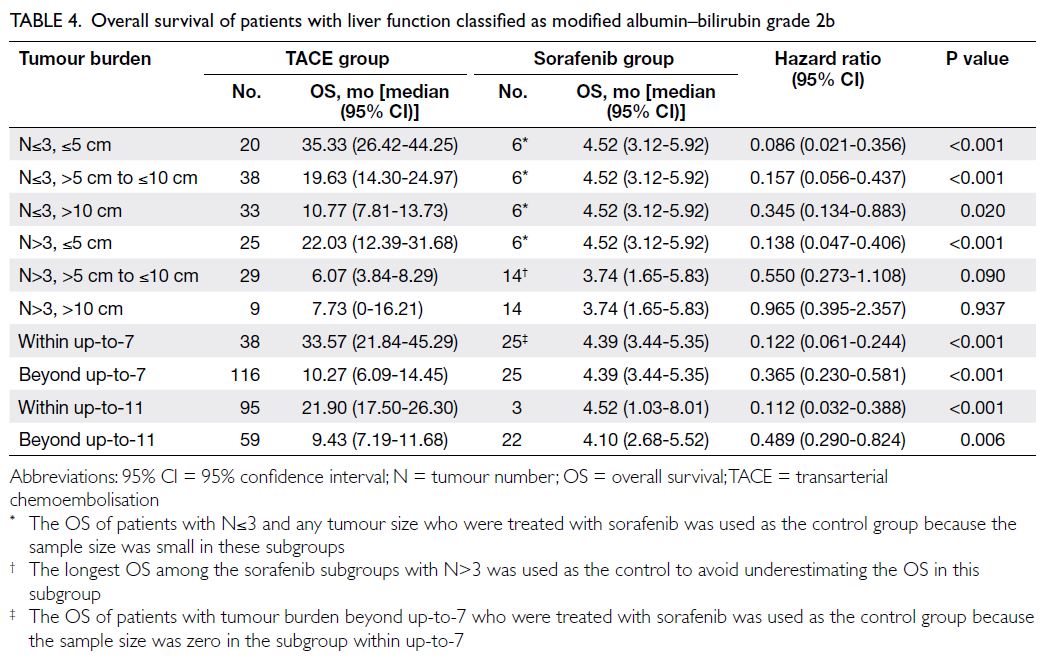

Overall survival in modified albumin–bilirubin grade 2b: transarterial

chemoembolisation versus sorafenib

In subgroups with mALBI grade 2b, defined by either the up-to-7 or up-to-11 criteria, patients

who received TACE exhibited significantly longer

median OS than those who received sorafenib

across all subgroups (all P<0.05; Table 4). However,

when using the N3-S5-S10 criteria, TACE resulted

in a significantly longer median OS than sorafenib

only in the subgroups with tumour number ≤3 (any

tumour size) and in the subgroup with tumour

number >3 and tumour size ≤5 cm (both P<0.05;

Table 4). In the subgroups with tumour number

>3 and tumour size >5 cm to ≤10 cm, and those

with tumour number >3 and tumour size >10 cm,

although TACE subgroups demonstrated longer

median OS than sorafenib subgroups (6.07 vs 3.74

months and 7.73 vs 3.74 months, respectively), the

differences were not statistically significant (Table 4).

Sensitivity analysis showed that survival was also not

significantly different between TACE and sorafenib

in the additional subgroup with tumour number ≤3

and tumour size >10 cm (HR=0.474 [95% CI=0.185-1.261]; P=0.120).

Table 4. Overall survival of patients with liver function classified as modified albumin–bilirubin grade 2b

Due to the small sample size, it was difficult

to demonstrate a clear survival benefit of TACE

over sorafenib; thus, the risk of overestimating the

survival benefit of TACE, due to potential bias from

more advanced disease in the sorafenib group, was

likely minimised. For example, given the limited

number of patients in the subgroups with tumour

number >3 and tumour size >5 cm to ≤10 cm and

those with tumour number >3 and tumour size >10

cm, these two subgroups were combined into one

subgroup (tumour number >3 and tumour size >5

cm). In this combined subgroup, TACE (n=38) still

yielded no significant survival benefit over sorafenib (n=14), with OS values of 6.07 months (4.10-8.03)

and 3.74 months (1.71-5.78), respectively (HR=0.586

[95% CI=0.325-1.054]; P=0.071).

Discussion

Results of subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis in this study revealed that, within

the limitations of the data, TACE probably did not

confer a statistically significant survival benefit over

sorafenib for patients with mALBI grade 2b and a

high tumour burden (number >3 and size >5 cm,

or number ≤3 and size >10 cm), or for patients with

mALBI grade 1 or 2a and tumour burden of number

>3 and size >10 cm. In contrast, TACE did provide a

survival benefit when the beyond up-to-7 or beyond

up-to-11 criteria were applied. These findings

suggest that the use of more precise criteria to

define tumour burden and liver function could help

identify specific subgroups unsuitable for TACE.

Such criteria highlight the threshold at which

TACE no longer provides a survival advantage over

sorafenib, thereby indicating TACE unsuitability.

These indicators would be valuable in guiding

the clinical management of intermediate-stage

HCC. The small sample size in the sorafenib group

may have limited the statistical power to detect a

survival benefit of TACE in subgroups with tumour

number >3 and size >5 cm. Given that the overall results showed a consistent trend favouring TACE,

validation through further studies with larger sample

sizes is warranted.

Sorafenib as a control

In recent years, systemic therapy for HCC has

undergone rapid development, leading to the

emergence of new drugs after sorafenib. The

combination of certain agents has shown significant

improvements in survival compared with sorafenib

alone. The IMbrave150 study demonstrated that

treatment with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab

resulted in a significantly longer median OS than

sorafenib alone (19.2 vs 13.4 months).17 Similarly,

both sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar18

and tremelimumab plus durvalumab19 provided

significant survival benefits over sorafenib in

patients with unresectable HCC. Nevertheless,

sorafenib remains the first-line standard treatment

and the most effective single agent for advanced

HCC. It serves as a benchmark for newer single-agent

therapies such as lenvatinib, nivolumab, and

durvalumab, which have shown statistical non-inferiority

in survival compared with sorafenib.19 20 21

Therefore, the use of sorafenib as the control arm

versus TACE in this study is reasonable. With

the rapid advancement of systemic agents, novel

treatment strategies—such as switching to systemic

therapy22 or initiating systemic therapy upfront followed by curative conversion23—have been

advocated for patients with intermediate-stage HCC

who may not benefit from TACE or repeated TACE.

In such cases, it is important to define specific

indicators of TACE unsuitability among patients

with intermediate-stage HCC, in whom systemic

therapy may potentially improve survival.

Deficiencies of conventional criteria

of unsuitability for transarterial

chemoembolisation

The concept of TACE unsuitability has emerged in

conjunction with the development and availability of

systemic therapies.24 In patients with intermediate-stage

HCC, TACE unsuitability has been defined as

the presence of mALBI grade 2b and tumour burden

beyond the up-to-7 criteria.25 26 This definition was

based on worse survival in patients with mALBI

grade 2b and the beyond up-to-7 criteria relative to

patients displaying better liver function and lower

tumour burden, without addressing the potential

survival benefit of TACE over alternative treatment

options in this subgroup. However, this definition

has two key limitations. First, it lacks clinical

evidence demonstrating greater survival benefit

from other alternative treatments when TACE

is withheld. Second, there remains controversy

regarding the optimal criteria for defining high

tumour burden. If the beyond up-to-7 criteria is

used as the criterion for TACE unsuitability, the

majority of patients with intermediate-stage HCC

would be considered unsuitable, which is both

unrealistic and unsupported. In the present study,

79% of patients had high tumour burden beyond up-to-7, comparable to the 70% reported by Hung et al.27

Limitations of conventional sub-staging

systems

The sub-staging system using the up-to-11 criteria

has shown better discriminatory power than

the up-to-7 criteria for predicting survival after

TACE.28 29 Nonetheless, in this study, neither the

up-to-7 nor the up-to-11 criteria were able to

identify TACE unsuitability. The findings indicated

that both the patient subgroup with mALBI grade

2b and tumour burden beyond the up-to-7 criteria,

as well as the subgroup with mALBI grade 2b and

tumour burden beyond the up-to-11 criteria, still

derived survival benefits from TACE compared

with sorafenib, indicating that these subgroups

should not be considered TACE unsuitable. The

lack of discriminatory power may be attributed to

the persistently high heterogeneity among patients

classified as having high tumour burden under to

these two criteria. Worse survival after TACE in

these subgroups, compared with patients displaying

better liver function and lower tumour burden, does not justify entirely abandoning TACE in these patients.

We propose using the N3-S5-S10 criteria

to define tumour burden, as these criteria allow

for more specific subgrouping and enable the

identification of TACE unsuitability with greater

precision, thereby reducing the likelihood of denying

patients a potentially beneficial treatment (TACE).

Our findings demonstrate that the proposed criteria

can identify TACE unsuitability precisely in specific

subgroups where the up-to-7 or up-to-11 criteria

fail to distinguish survival differences. Based on

these findings, we recommend that physicians assess

intermediate-stage HCC using both the mALBI

grade and the N3-S5-S10 criteria—a more rigorous

framework—to determine TACE unsuitability. To

our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate

the survival benefit of TACE over sorafenib in

patients with intermediate-stage HCC stratified by

both liver function and tumour burden, as well as to

identify TACE unsuitability within these subgroups.

Limitations

This study provided a larger sample size than previous

studies comparing survival benefits between TACE

and sorafenib. However, several limitations should

be noted. First, the retrospective design of this study

inevitably introduced patient selection bias between

the TACE and sorafenib groups. Although there

were significant differences in age, sex, and tumour

size between the groups, such disparities in overall

patient demographics might not have critically

affected the validity of the survival comparisons,

given that these were based on subgroup analyses.

Second, the sample size was exceedingly small in

some sorafenib subgroups with low tumour burden.

The substantial disparity in patient numbers may

have contributed to non-significant differences in

OS between subgroups. We attempted to mitigate

this limitation by combining subgroups with very

small sample sizes. Third, some patients in the

TACE group received systemic therapy after disease

progression. Consequently, survival in the TACE

group may have been overestimated as it reflected

outcomes of TACE with or without systemic therapy,

rather than TACE alone. Nonetheless, ‘TACE

followed by systemic therapy’ represents standard

clinical practice aimed at achieving the greatest

patient benefit, and isolating a TACE-alone group

for analysis would not be realistic. Notably, ‘TACE

followed by systemic therapy’ accurately reflects

real-world treatment practice and does not conflict

with the study’s primary objective, which was to

define specific indicators of TACE unsuitability

at baseline rather than at the point when TACE

becomes unsuitable. Finally, no power calculation

was performed in the statistical analysis.

Conclusion

More precise criteria for TACE unsuitability are

required. The combination of mALBI grade and

N3-S5-S10 criteria may serve as a better indicator

of TACE unsuitability than the beyond up-to-7

or beyond up-to-11 criteria for patients with

intermediate-stage HCC. TACE likely offers no

survival benefit compared with sorafenib beyond

these thresholds. However, validation in a larger

cohort is warranted.

Author contributions

Concept or design: SCH Yu.

Acquisition of data: LM Chen, L Li, EP Hui, W Yeo, SL Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: LM Chen, SCH Yu.

Drafting of the manuscript: LM Chen, SCH Yu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: LM Chen, L Li, EP Hui, W Yeo, SL Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: LM Chen, SCH Yu.

Drafting of the manuscript: LM Chen, SCH Yu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research was funded by the Vascular and Interventional

Radiology Foundation, Hong Kong. The funding body was not

involved in the design of the study, collection of data, analysis/interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by The Chinese University of Hong

Kong–New Territories East Cluster Ethics Committee, Hong

Kong (Ref No.: 2020.672). It was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference

on Harmonisation–Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The

requirement for written informed patient consent was waived

by the Committee due to the retrospective nature of the

research.

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics

2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality

worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J

Clin 2021;71:209-49. Crossref

2. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, et al. Arterial embolisation

or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in

patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a

randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:1734-9. Crossref

3. Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. Randomized controlled

trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for

unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology

2002;35:1164-71. Crossref

4. Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized

trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma:

chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology Feb

2003;37:429-42. Crossref

5. Bolondi L, Burroughs A, Dufour JF, et al. Heterogeneity

of patients with intermediate (BCLC B) hepatocellular

carcinoma: proposal for a subclassification to facilitate

treatment decisions. Semin Liver Dis 2012;32:348-59. Crossref

6. Kudo M, Arizumi T, Ueshima K, Sakurai T, Kitano M,

Nishida N. Subclassification of BCLC B stage hepatocellular

carcinoma and treatment strategies: proposal of modified

Bolondi’s subclassification (Kinki criteria). Dig Dis

2015;33:751-8. Crossref

7. Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Nouso K, et al. Proposed new sub-grouping

for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma

using albumin–bilirubin grade. Oncology 2016;91:153-61. Crossref

8. Arizumi T, Ueshima K, Iwanishi M, et al. Validation of

Kinki criteria, a modified substaging system, in patients

with intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis

2016;34:671-8. Crossref

9. Bruix J, Raoul JL, Sherman M, et al. Efficacy and safety

of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular

carcinoma: subanalyses of a phase III trial. J Hepatol

2012;57:821-9. Crossref

10. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety

of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region

with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III

randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet

Oncol 2009;10:25-34. Crossref

11. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med

2008;359:378-90. Crossref

12. Iavarone M, Cabibbo G, Piscaglia F, et al. Field-practice

study of sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma:

a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Hepatology

2011;54:2055-63. Crossref

13. Marrero JA, Kudo M, Venook AP, et al. Observational

registry of sorafenib use in clinical practice across

Child-Pugh subgroups: the GIDEON study. J Hepatol

2016;65:1140-7. Crossref

14. Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Kumada T, et al. Validation and

potential of albumin–bilirubin grade and prognostication

in a nationwide survey of 46,681 hepatocellular carcinoma

patients in Japan: the need for a more detailed evaluation

of hepatic function. Liver Cancer 2017;6:325-36. Crossref

15. Yu SC, Hui JW, Hui EP, et al. Unresectable hepatocellular

carcinoma: randomized controlled trial of transarterial

ethanol ablation versus transcatheter arterial

chemoembolization. Radiology 2014;270:607-20. Crossref

16. Yu SC, Hui JW, Li L, et al. Comparison of

chemoembolization, radioembolization, and transarterial

ethanol ablation for huge hepatocellular carcinoma (≥10

cm) in tumour response and long-term survival outcome.

Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2022;45:172-81. Crossref

17. Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Updated efficacy and safety

data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab

vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J

Hepatol 2022;76:862-73. Crossref

18. Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, et al. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab

biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable

hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomised,

open-label, phase 2-3 study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:977-90. Crossref

19. Abou-Alfa GK, Chan SL, Kudo M, et al. Phase 3 randomized,

open-label, multicenter study of tremelimumab (T) and

durvalumab (D) as first-line therapy in patients (pts)

with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC):

HIMALAYA. J Clin Oncol 2022;40(4_suppl):379. Crossref

20. Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, et al. Nivolumab versus sorafenib

in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 459): a

randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol 2022;23:77-90. Crossref

21. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib

in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable

hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority

trial. Lancet 2018;391:1163-73. Crossref

22. Ogasawara S, Ooka Y, Koroki K, et al. Switching to systemic

therapy after locoregional treatment failure: definition and

best timing. Clin Mol Hepatol 2020;26:155-62. Crossref

23. Kudo M. A novel treatment strategy for patients with

intermediate-stage HCC who are not suitable for TACE:

upfront systemic therapy followed by curative conversion.

Liver Cancer 2021;10:539-44. Crossref

24. Kudo M. Extremely high objective response rate of

lenvatinib: its clinical relevance and changing the

treatment paradigm in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver

Cancer 2018;7:215-24. Crossref

25. Kudo M, Han KH, Ye SL, et al. A changing paradigm for the

treatment of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma:

Asia-Pacific Primary Liver Cancer Expert Consensus

Statements. Liver Cancer 2020;9:245-60. Crossref

26. Kudo M, Kawamura Y, Hasegawa K, et al. Management

of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: JSH Consensus

Statements and Recommendations 2021 update. Liver

Cancer 2021;10:181-223. Crossref

27. Hung YW, Lee IC, Chi CT, et al. Redefining tumor burden in

patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma:

the seven-eleven criteria. Liver Cancer 2021;10:629-40. Crossref

28. Kim JH, Shim JH, Lee HC, et al. New intermediate-stage

subclassification for patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization.

Liver Int 2017;37:1861-8. Crossref

29. Lee IC, Hung YW, Liu CA, et al. A new ALBI-based model

to predict survival after transarterial chemoembolization

for BCLC stage B hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int

2019;39:1704-12. Crossref