© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

SPECIAL ARTICLE

Medical history of Hong Kong

Introduction—Anatomy of a city: why Hong

Kong’s history of medicine matters now

Ria Sinha, BSc, PhD

Medical Ethics and Humanities Unit, School of Clinical Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Ria Sinha (riasinha@hku.hk)

As COVID-19 fades from view, the most significant

pandemic of the 21st century is already being

written into history. Hong Kong’s experience of

the coronavirus outbreak was both local and yet

enmeshed in global networks of disease transmission,

biomedicine, technology, geopolitics and public

response. How one wonders, will the story be told

to future generations of schoolchildren, medical

students, health professionals and the public? Over

time, a singular narrative often emerges, defined by

the major events of the outbreak, with the messiness

of everyday details, early public uncertainty, frequent

policy changes and misinformation gradually erased

from memory. Given the mountain of information

that emerged and changed on a daily basis, this is

inevitable, but medical historiographies should

preserve this complexity to ensure a balanced and

critical analysis of present and future events.

A maritime entrepôt frequently reshaped by

migration, imperial power, political turmoil, and

capitalist ambitions, Hong Kong has long been

at the mercy of local, regional and global health

threats. From 19th-century communicable diseases

to 21st-century pandemics and chronic health

conditions, from bacteriology’s early laboratories

to genomics and precision medicine, and from

missionary, government and private hospitals to a

plural public health system, the city’s medical story

is one of collisions and entanglements, between

people, pathogens, medical systems, institutions,

and technological innovation. This exciting and

timely new series on Hong Kong’s rich history of

medicine endeavours to bring diverse local archives

and stories to life, reminding us of the challenges of

the foregone medical landscape and the endeavours

of those who sought to construct the robust medical

system we benefit from today.

Challenges in health governance

and building local medical capacity

Countless medical and healthcare professionals

contributed to shaping local medical expertise, laying a foundation to serve the needs of a mixed

and growing population. Local capacity building was

often hampered by economic constraints imposed

by the British Government and the city was reliant

on transient doctors for much of the 19th century,

from naval surgeons to private practitioners, as

well as grassroots traditional Chinese medicine

practitioners who ministered to local and migrant

Chinese communities. Yet early medical practice

was challenging, and several Colonial Surgeons died

in service or from complications of repeated bouts

of sickness after leaving the colony.1 Efforts to unify

physicians and consolidate knowledge were initially

limited to Western medicine practitioners through

the formation of the China Medico-Chirurgical

Society, but diaries and journals show there was

professional interest in the healing properties of

Chinese medicine.2 Attempts to establish Western

medicine as a primary healthcare framework

for the majority Chinese population began with

early medical missionaries under the auspices of

the London Missionary Society, but success was

dependent on circumstance, government policies

and funding. There were also well-intentioned yet

culturally problematic endeavours to shoehorn

Chinese medicine, which was largely community

based, into an institutional model, as seen in the case

of Tung Wah Hospital, which opened in 1872 at the

heart of the Chinese community but was returned to

colonial oversight after the plague outbreak.3

A decisive development was the founding of the

Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese in 1887,

a forerunner of The University of Hong Kong’s Faculty

of Medicine. The College represented a loftier late

19th century effort to translate biomedical science

into Chinese settings, training local practitioners to

expand the reach of Western medicine into China.4

Women’s and children’s health nonetheless lagged

behind and was dependent on the timely presence

and dogged determination of individuals such as Dr

Alice Hickling, who galvanised government support

and funding for maternity services.5 Mental health,

too, has a long and troubled history in Hong Kong,

complicated by a lack of knowledge, appropriate facilities and empathy towards the afflicted.6 The

subsequent establishment of large teaching hospitals

promoted the professionalisation of nursing, the

emergence of more locally trained physicians and

allied health professionals, and ultimately led to

the formation of the Hospital Authority in 1990 to

manage public hospitals. This gradually expanded

and embedded medical practices in the city’s social

fabric, while connecting Hong Kong to British,

Chinese, and global networks.

Hong Kong as a node in local and

global medical history

Hong Kong’s history situates local practice within

global circuits of knowledge, and few cities

exemplify the globality of medicine as vividly as

Hong Kong. The territory has always been a hub,

a place of opportunity, trade and new beginnings

propelled by high mobility. As the population grew

and communication and transportation channels

expanded, port health controls became essential to

screen for deadly diseases such as smallpox, various

febrile diseases, and distant threats such as yellow

fever. Syphilis was a prime example of a well-travelled

and much-feared sexually transmitted disease that

quickly became established in the squalid brothels

and among unregulated sex workers, driven by a

gender imbalance and propagated by thousands of

transiting naval personnel and Chinese immigrants.7

Such episodes compelled the instatement of

successive, though sometimes repressive, health

policies to manage the situation and treat the afflicted. The colonial government frequently drew

on British experiences and laws as a remedy but was

often unprepared for the challenges of governing a

multicultural population.

The colonial port’s early public health regimen

was severely tested during the 1894 bubonic plague,

an outbreak that began in Yunnan, China, and

spread along trade routes to reach the overcrowded

residential districts of Hong Kong before extending

to India and around the globe. The Hong Kong

outbreak drew international scientific teams to

the territory and sparked debates over science and

urban sanitation methods that often intersected

with racialised assumptions and coercive policies.

It is a history that has been retold through multiple

disciplinary perspectives and invites ethical

reflection, but the crisis undoubtedly catalysed

extensive and controversial sanitary reforms, urban

planning and biomedical infrastructure development

to facilitate homegrown laboratory-based public

health.8 Socio-medical transformations following

the outbreak reinforced how crisis events can shape

public health policies for generations.

The late 20th century brought fresh forms of

global interdependence and collaboration. The 1997

H5N1 avian influenza outbreak underscored the

city’s international role in pandemic surveillance

and the fragile boundaries between human and

animal health.9 Six years later, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) swept through

hospitals, housing estates, and international

flight paths, exposing the vulnerabilities of dense

urban living and rapid global mobility. Hong Kong

scientists, epidemiologists, medical professionals, and public health officials were pivotal in identifying

the causative pathogens, sharing information,

and controlling the outbreak.10 The aftermath saw

institutional reforms, including the establishment

of the Centre for Health Protection, and a durable

model for infection control and public health

governance that was tested during COVID-19.

Why preserving this history

matters now and for the future

Juggling a packed curriculum, medical students have

questioned why they should spend time learning

medical history. There are many pertinent responses,

but one that seems particularly relevant is that

history affords a critical perspective on medicine,

professional culture, identity and practice.11 One of

the most effective ways to actuate this is by embedding

interactive engagement into the curriculum through

field trips to museums, designing walking tours,

and encouraging self-directed research and learning

activities. Hong Kong is blessed with a fantastically

rich medical heritage, and witnessing this history

in the community and on the streets is a powerful

experiential tool to stimulate self-awareness, inspire

lifelong learning, and promote knowledge exchange

between health practitioners and the public. Indeed,

some medical historiographies demand reflection to

avoid future error. Trust is partly historical memory,

preserving and sharing authentic, accessible

historical narratives through museums, archives,

journals and innovative curricula that can stimulate

more participatory and forward-thinking forms of

health governance.

History also permits us to see into the future,

not in the conventional sense of ‘learning lessons

from the past’, which can be a problematic trope,

but in understanding local vulnerabilities to disease

and gaps in infrastructure or expertise. The recent

opening of a flagship Chinese Medicine Hospital

in Tseung Kwan O is testament to a post-handover

revival of traditional Chinese medicine, driven

by the Chinese Medicine Ordinance (Cap 549)

and the persistence of local healing cultures in the

community. Today, a visit to Watson’s pharmacy,

one of the oldest (Western medicine) dispensaries

in Hong Kong dating to the 1840s, reveals an array

of prepackaged Chinese medicines and a Chinese

medicine consultation booth. The question of

medical pluralism and potential for integrating these

divergent medical frameworks is an interesting one

that will benefit from further examination of their

historical coexistence.

To conclude, Hong Kong’s medical evolution

has been nothing short of remarkable, characterised

by local idiosyncrasies within a broader global

health network. Preserving and disseminating Hong Kong’s rich medical history is both a

collective responsibility and an opportunity

for interdisciplinary knowledge exchange.

Professionally, historical literacy supports leadership

and informs decision making and policy design. By

working together, health professionals and historians

can co-translate scattered memories into shared

knowledge, and shared knowledge into better care

and medical development. In a period of fast-moving

technological innovation, it is more important than

ever to capture local histories as a window to Hong

Kong’s medical development legacy and to avoid

the perpetuation of inaccurate information and

sources.

This series invites clinicians, nurses, allied

health professionals, public health practitioners, and

students to read Hong Kong’s medical past not as a

linear story but as a critical reflection that informs

medical and scientific progress. Many health topics

deserve historical attention and are too many to

discuss in this brief introduction, but a diverse series

will surely emerge. Upcoming articles will build

on existing histories of medicine, enriching Hong

Kong’s material culture of medicine and inspiring

a new generation of custodians. In a city where

the future is always arriving early, history can be a

valuable partner in foresight.

References

1. Lim P. Forgotten Souls: A Social History of the Hong Kong

Cemetery. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2011:

145-9. Crossref

2. Rydings HA. Transactions of the China Medico-

Chirurgical Society, 1845-6. J Hong Kong Branch R Asiat

Soc 1973;13:13-27.

3. Sinn E. Power and Charity: A Chinese Merchant Elite in

Colonial Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University

Press; 2003. Crossref

4. Ching F. 130 Years of Medicine in Hong Kong: From the

College of Medicine for Chinese to the Li Ka Shing Faculty

of Medicine. Singapore: Springer; 2018. Crossref

5. Chan-Yeung M. Dr Alice Hickling (1876-1928): the doctor

who changed the paradigm of maternal care in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong Med J 2021;27:389-91. Crossref

6. Wu HJ. From means to goal: a history of mental health

in Hong Kong from 1850 to 1960. In: Minas H, Lewis M,

editors. Mental Health in China and the Chinese Diaspora:

Historical and Cultural Perspectives. Cham, Switzerland:

Springer; 2021: 69-78. Crossref

7. Tsang CC. Hong Kong’s floating world: disease and crime

at the edge of empire. In: Peckham R, editor. Disease

and Crime: A History of Social Pathologies and the New

Politics of Health. Routledge; 2014: 21-39.

8. Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society. Plague,

SARS and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. Hong

Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2006: 147-224.

9. Malik Peiris JS, de Jong MD, Guan Y. Avian influenza virus

(H5N1): a threat to human health. Clin Microbiol Rev

2007;20:243-67. Crossref

10. Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL, et al. Coronavirus as a possible

cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet

2003;361:1319-25. Crossref

11. Nagornykh O. Integrating the history of medicine into modern medical education: evidence-based structures,

methods, and relevance. 28 May 2025. Available from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5274761. Accessed 10 Jan 2026.

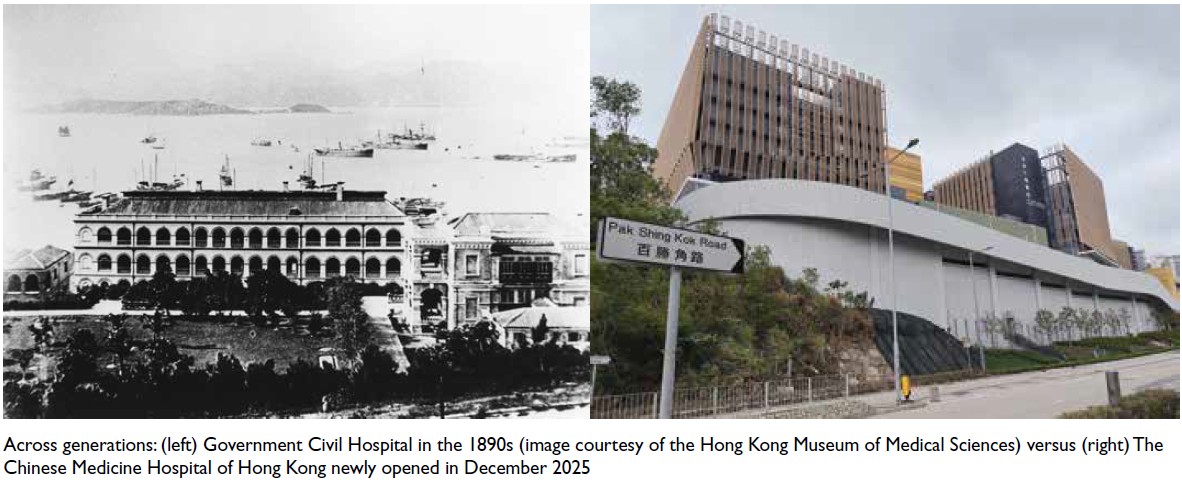

Across generations: (left) Government Civil Hospital in the 1890s (image courtesy of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences) versus (right) The Chinese Medicine Hospital of Hong Kong newly opened in December 2025