© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Profiling unmet post–acute care needs of an

inpatient population in Hong Kong: can real-world data and machine learning algorithms bring precision to tertiary prevention in the community?

Eman Leung, PhD1,2; Jingjing Guan, PhD3; Frank Youhua Chen, PhD1; Sam CC Ching, BBA2; Hector Tsang, PhD4; Martin CS Wong, MD, FHKAM (Family Medicine)2; Olivia Lam, MPH2; Yinan He, MPH2; Sarah TY Yau, MPH2; Yilin Liu, MPH2; CB Law, MB, BS5; NY Chan, MB, BS5; YF Wong, PhD5; YH Chow, BSocSc6; CT Hung, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)2; EK Yeoh, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Albert Lee, MD, FHKAM (Family Medicine)2,4,7

1 Department of Management Sciences, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 EpitelligenceHK, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Rehabilitation Science, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Kowloon West Cluster, Princess Margaret Hospital and North Lantau Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 Kwai Tsing Safe Community and Healthy City Association, Hong Kong SAR, China

7 Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion, The Jockey Club

School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of

Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Albert Lee (alee@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Case-mix systems aim to optimise

acute care resource allocation, yet patients within

the same groups often exhibit substantial variability

in utilisation. This study aimed to examine how

incorporating measures of clinical complexity

and post–acute care utilisation—both critical

to rehospitalisation risk and accurate resource

planning—into case-mix stratification could improve

the precision of acute care resource allocation.

Methods: Through iterative applications of

unsupervised and supervised machine learning

models, we extracted typical patient profiles

from the study populations, analysed post–acute

care utilisation patterns, and assessed the 28-day

rehospitalisation rates resulting from different

pairings between clinical profiles and post–acute

care service utilisation patterns.

Results: Across various disease systems and age-groups,

patients discharged without receiving

algorithm-selected post–acute care (ie, No Service

groups [NS groups]) showed significantly higher

28-day rehospitalisation rates relative to their

corresponding segments in the same medoid case-mix

groups (CMGs; pooled odds ratio [OR]=19.27;

P<0.001). The NS groups also demonstrated higher

rates of having two or more chronic diseases

(pooled OR=1.84; P<0.001) and—for the 50-64–year-old population—resource-intensifying co-morbidities

(pooled OR=1.23; P=0.05). Patients

displaying higher rates of resource-intensifying

co-morbidities compared with their ≥65-year-old

counterparts (such as when the medoid CMG was

renal failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease) also exhibited significantly higher 28-day

rehospitalisation rates than the ≥65–year-old NS

groups sharing the same medoid CMGs.

Conclusion: These findings support a precision-driven approach to designing rehospitalisation

prevention programmes that target individuals

aged 50 to 64 years discharged with specific clinical

profiles, and developing and allocating human

capital for these targeted prevention programmes.

New knowledge added by this study

- Our novel machine learning analyses revealed that ambulatory care–sensitive conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and general digestive symptoms were the diagnoses received by patients who were ‘typical’ (ie, the medoid) of the studied inpatient population and its subpopulations of patients with unmet post–acute care needs.

- Higher proportions of patients aged 50 to 64 years in the subpopulations had histories of two or more chronic illnesses prior to the index hospitalisation, had resource-intensifying co-morbidities at the index hospitalisation, and rehospitalised within 28 days after being discharged.

- Tertiary prevention programmes targeting specific profiles of individuals aged 50 to 64 years who are discharged into the community can help relieve the burden on hospital services.

- The integration of post–acute care utilisation data and clinical complexity indicators into population stratification can improve the precision of tertiary prevention planning and resource allocation across community and hospital settings.

Introduction

To standardise clinical practices and inform

targeted policy decisions, major health systems

segment their populations into case-mix groups

(CMGs). With expert input and analytical methods,

CMGs are designed with optimal granularity—balancing individual-level clinical care decisions and

population-level acute care resource allocation1—and judicious parsimony, selecting indicators from

the wealth of information extracted from patient

electronic health records (see online supplementary Table 1 for a comparison of major healthcare systems’

case-mix frameworks).

However, clinical case-mix systems often

provide imperfect estimations of their populations’

acute care utilisation.2 3 4 It has been suggested that

critical drivers of acute care admissions and 28-day

rehospitalisations, such as clinical complexity,5 6

are not often included as indicators for stratifying

patients. Also, the linkage between case mixes of

populations and their respective post–acute care

(PAC) needs has not been established, although

PAC can reduce rehospitalisations and mitigate

the rehospitalisation risk associated with clinical

complexity.7 In fact, not only have the PAC needs

of patients discharged under various case-mix

classifications remained unexplored, but studies

examining the effects of PAC on acute care utilisation

often fail to consider the diversity of PAC service

types8 9 and their differential effects on patients

with distinct clinical profiles.10 11 12

Therefore, this study aimed to identify the

factors contributing to the discrepancy between

the objectives of case-mix systems—optimising the

efficient allocation of acute care resources—and

the observed heterogeneity in acute care utilisation

among patients within the same CMGs. Specifically,

although clinical complexity and PAC utilisation

influence the rehospitalisation risk of discharged

patients—which in turn affects the accuracy of

population-level acute care resource planning—they are not typically included in case-mix systems for patient stratification. Thus, we examined the

heterogeneity and relationships among clinical

complexity, PAC utilisation, and rehospitalisation

risk within homogeneous patient segments.

These segments were partitioned from the study

population using conventional case-mix parameters

and acute care utilisation metrics. Given this

context, we hypothesised that among patients within

the same homogeneous segments, those who did not receive effective PAC would exhibit the highest

rates of 28-day rehospitalisation. Additionally, we

hypothesised that greater clinical complexity would

increase the likelihood of rehospitalisation occurring

before receipt of any effective PAC.

Methods

Study population

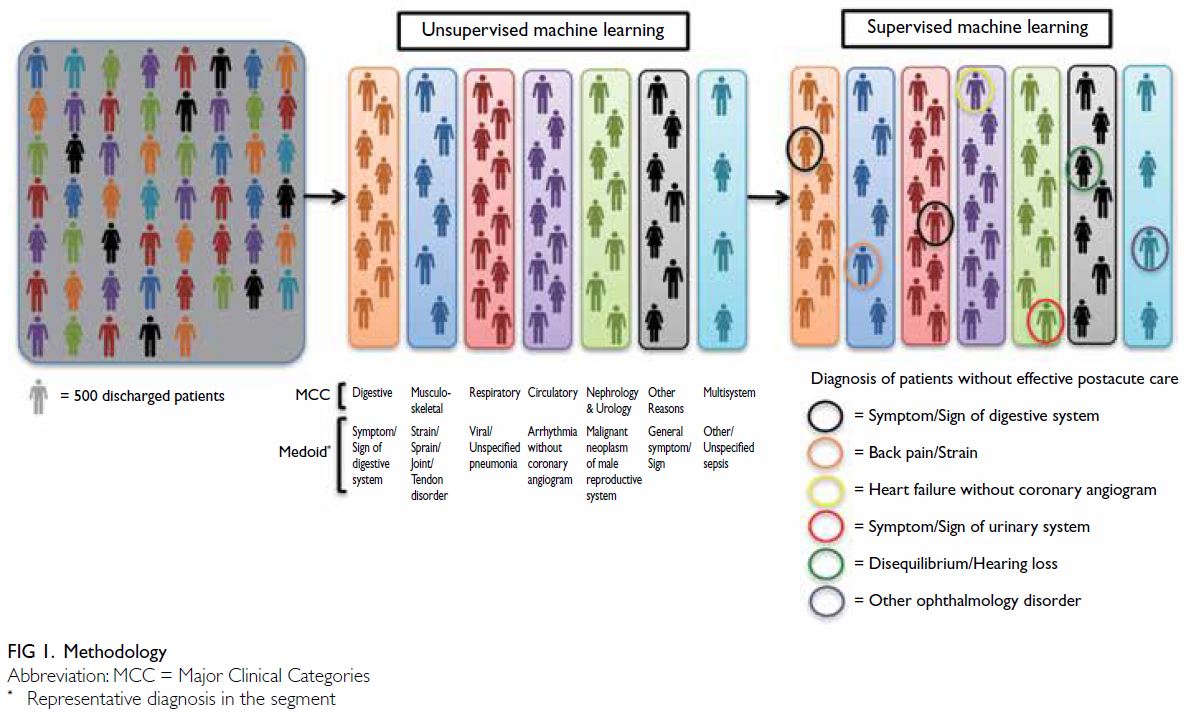

In this study of an inpatient population of 197 805

individuals (aged >50 years) discharged into the

community, a combination of unsupervised and

supervised learning algorithms was deployed (Fig 1).

First, unsupervised learning algorithms were applied

to identify typical patients (ie, medoids) using a

comprehensive set of clinical parameters (including

discharged patients’ CMGs) and acute care

utilisation data.13 Patients similar to typical patients

in terms of these parameters were clustered into the

same segments. Each resulting segment was labelled

according to the Major Clinical Category (MCC)13

assigned to its medoid. According to case-mix

methodologies adopted by major healthcare systems

(eg, CMG+ of Canada13), the MCC reflects the

primary body system or medical specialty involved

and provides a high-level overview of the patient’s

condition. Within each MCC, patients are further

classified into more specific CMGs based on detailed clinical and resource utilisation characteristics. We

therefore expected that patients within the same

segment would share the same MCC as the medoid,

although their CMGs might differ. Consequently,

each segment was labelled with the medoid’s MCC.

The International Classification of Diseases codes

constituting each CMG and the corresponding MCC

for each are shown in online supplementary Table 2.

Study design

Second, with additional features representing

the types and timing of PAC service utilisation,

28-day rehospitalisation outcome–supervised

machine learning algorithms (Unbiased Recursive

Partitioning with Surrogate Splitting [URPSS]14)

were applied to recursively partition clinically

homogeneous segments into subpopulations, each

characterised by homogeneous PAC utilisation. The

URPSS has previously been used to compare the

effects of clinical profiles and acute care utilisation

on 28-day rehospitalisations with those of different

PAC service types, isolating the unique contribution

of patients’ clinical and acute care factors.15 In this

study, we adopted a complementary approach by

isolating each PAC service type’s unique contribution

to 28-day rehospitalisation while adjusting for

the influence of the end user’s clinical profile and

acute care utilisation. To achieve this approach, we first partitioned the population into segments with

homogeneous clinical and acute care utilisation

profiles. Within each segment, the URPSS algorithm

was then applied to infer the effects of PAC on

28-day rehospitalisation, contingent on patients’

clinical and acute care characteristics. A detailed

description of the hybrid machine learning approach

used to disentangle post-acute from acute influences

is provided in the online Appendix.14 15 16

Among the different subpopulations

partitioned from each segment, one inevitably

remained unpartitioned by any feature representing

the PAC services for which the algorithm found

significant conditional inferences on 28-day

rehospitalisation. We hypothesised that this

unpartitioned subpopulation—representing patients

whose acute care needs (as reflected by the

comprehensive segmenting features of clinical and

acute care utilisation parameters) were homogeneous

with others in the same segment but who lacked any

28-day rehospitalisation–mitigating PAC services—would exhibit the highest clinical complexity and

28-day rehospitalisation rates. These groups of

discharged patients, whose rehospitalisation risk

was high but who lacked algorithm-selected PAC

services, are hereafter referred to as the No Service

groups (NS groups).

In conjunction with the 28-day rehospitalisation

rate, the prevalence of clinical complexity—reflected

by the presence of two or more chronic illnesses

diagnosed prior to the index hospitalisation and

by acute care resource-intensifying co-morbid

diagnoses at index hospitalisation5 6—was also

compared between the NS groups and their

corresponding segments. We hypothesised that

greater clinical complexity would be associated

with an increased likelihood of patients being

rehospitalised before receiving any effective PAC.

Comparisons were also made between populations

aged 50-64 years and 65 years or above. Research has

shown that adults aged 50 to 64 years face unique

health challenges and experience care gaps not

observed among those aged 65 years or above.16 In

particular, care gaps predominantly affecting the

50-64 age-group have been linked to inaccuracies

in predicting patients’ acute care needs using case-mix

models,17 which were primarily developed from

inpatient populations aged 65 years and older.18 19 20 21

Although many comparisons could be made

between the NS groups and their corresponding

segments across all segments partitioned from the

50-64–year-old or ≥65–year-old populations—and

between the NS groups or segments of the two

populations—comparisons were restricted to the NS

groups and their corresponding segments that shared

the same medoid CMGs, to ensure homogeneity in

clinical and acute care utilisation profiles between the

subgroups being compared. Similarly, comparisons between the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old NS

groups or between the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old segments were confined to pairs with the

same medoid CMGs. The odds ratios (ORs), 95%

confidence intervals (95% CIs), and P values resulting

from comparisons between each same-CMG pair

for clinical complexity and 28-day rehospitalisation

were calculated from a subset of the descriptive

statistics reported in online supplementary Tables 3 (for the 50-64–year-old age-group) and 4 (for the ≥65–year-old age-group). In addition to the

presence of data regarding the prevalence of clinical

complexity and 28-day rehospitalisations, these

supplementary tables include the comprehensive set

of features that: (1) constitute the CMGs adopted

in this study, (2) segment the 50-64–year-old and

≥65–year-old populations, and (3) partition each

segment to identify its corresponding NS groups.

These features encompass diagnoses, age, sex,

resource-intensive interventions received at index

acute care hospitalisation, and resource-intensifying

co-morbidities diagnosed at index acute care

hospitalisation. Given that the contributions of these

features to clinical profile variability had already

been adjusted for through multiple iterations,

they were unlikely to be selected by the URPSS

algorithm to split a segment into subpopulations.

Our focus therefore remained on demonstrating the

high prevalence of clinical complexity and 28-day

rehospitalisation among the NS groups, rather than

on features not selected by the URPSS.

We tested our hypotheses regarding the

elevated risks of the NS groups compared with their

parent segments (particularly for the 50-64–year-old

population) through selected paired comparisons

and omnibus testing. By aggregating results

across different same-CMG pairs, we followed the

standard epidemiological practice of utilising all

available evidence from various subgroups within

a single sample to maximise the robustness and

generalisability of estimates while adjusting for

inherent sample stratification.22 23 Indeed, whereas

analysis of an entire sample may overlook underlying

confounding factors, a strong focus on stratified

subgroup analyses can lead to misinterpretations

that inflate the effects of confounding variables on

outcomes and distort the relationships between risk

factors and outcomes.24 25 To quantify the likelihood

of clinical complexity and 28-day rehospitalisation

rates in the NS groups versus their parent segments,

we pooled ORs using the Mantel-Haenszel formula26

across same-CMG pairs within each age population

and between the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old

populations (calculated from the ORs and associated

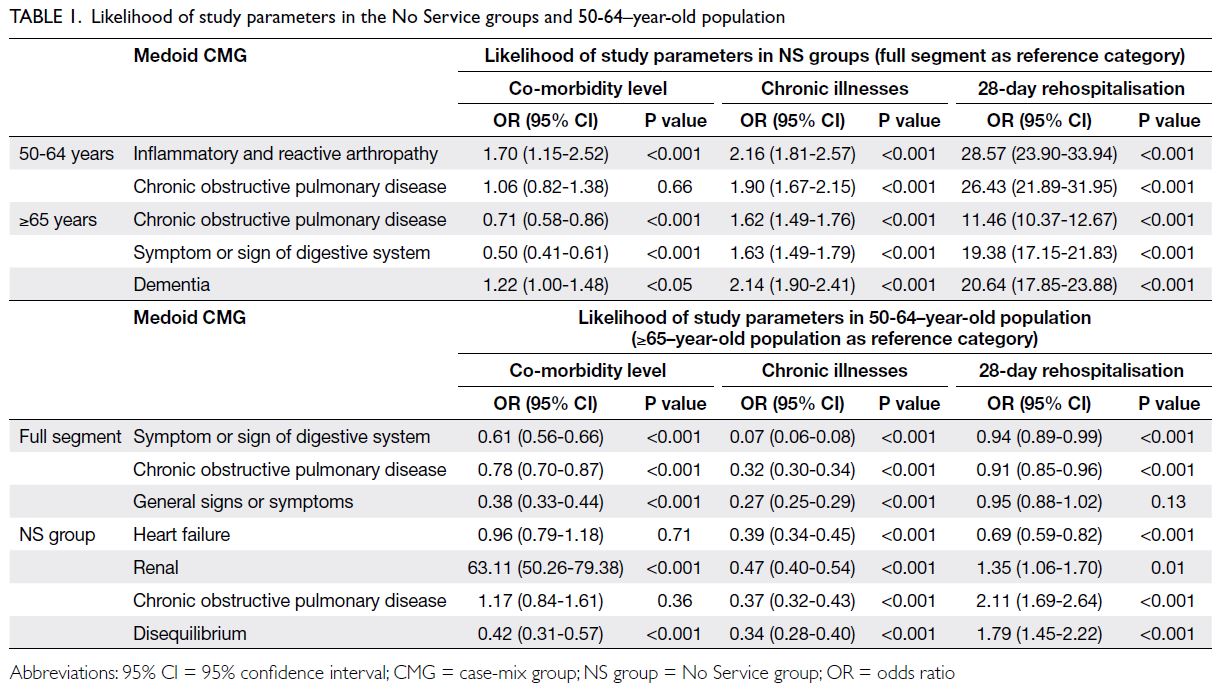

95% CIs and P values reported in Table 1). This

approach allowed us to evaluate overall differences

in co-morbidity, chronic illnesses, and 28-day

rehospitalisations between age-groups and between the NS groups and their corresponding segments.

The Mantel-Haenszel formula has been applied in

diverse clinical contexts involving a single patient

sample or population, including a targeted patient

group with traumatic brain injury,27 a regional

population admitted from multiple hospitals with

different major diagnoses,28 and a case-control

study combining matched and unmatched control

groups.29 Results reported below include pooled

ORs, 95% CIs, P values, and, where applicable, Q

statistics with corresponding P values to indicate

significant heterogeneity among pooled ORs.

Results

Below, we describe the clinical profiles of typical

patients (medoids) in the 50-64–year-old and

≥65–year-old populations and their corresponding

population segments. We then report the order in

which the URPSS algorithm selected PAC services

based on their unique statistical importance in

classifying 28-day rehospitalisation. We also

characterise the clinical profiles of patients who

received none of the URPSS-selected PAC services

(ie, the NS groups). Finally, we compare the rates of

resource-intensifying co-morbidities, the presence

of two or more chronic diseases, and 28-day

rehospitalisations between the NS groups and their corresponding segments, as well as between the

50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old populations.

Profiles of typical patients and associated

segments in the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old populations

The Calinski–Harabasz index indicated that the

optimal number of segments was seven for the

50-64–year-old population and eight for the ≥65–year-old population.30 Our analyses revealed that

the seven typical patients identified in the 50-64–year-old population belonged to the same MCCs as

their counterparts in the ≥65–year-old population:

Circulatory, Digestive, Nephrology and urology,

Musculoskeletal, Respiratory, Multiple systems

of diseases and disorders, and Other reasons for

hospitalisation. Additionally, four MCCs shared

between the two age-groups were characterised by

identical CMGs: Symptom or sign of digestive system

(Digestive), Malignant neoplasm of urinary system

(Nephrology and urology), Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (Respiratory), and General

symptom or sign (Other reasons for hospitalisation).

In the ≥65–year-old population, we identified an

eighth segment, whose typical patient’s CMG was

dementia, belonging to the MCC of Diseases and

disorders of the mental system.

Utilisation of post–acute care services and

associated 28-day rehospitalisation rates

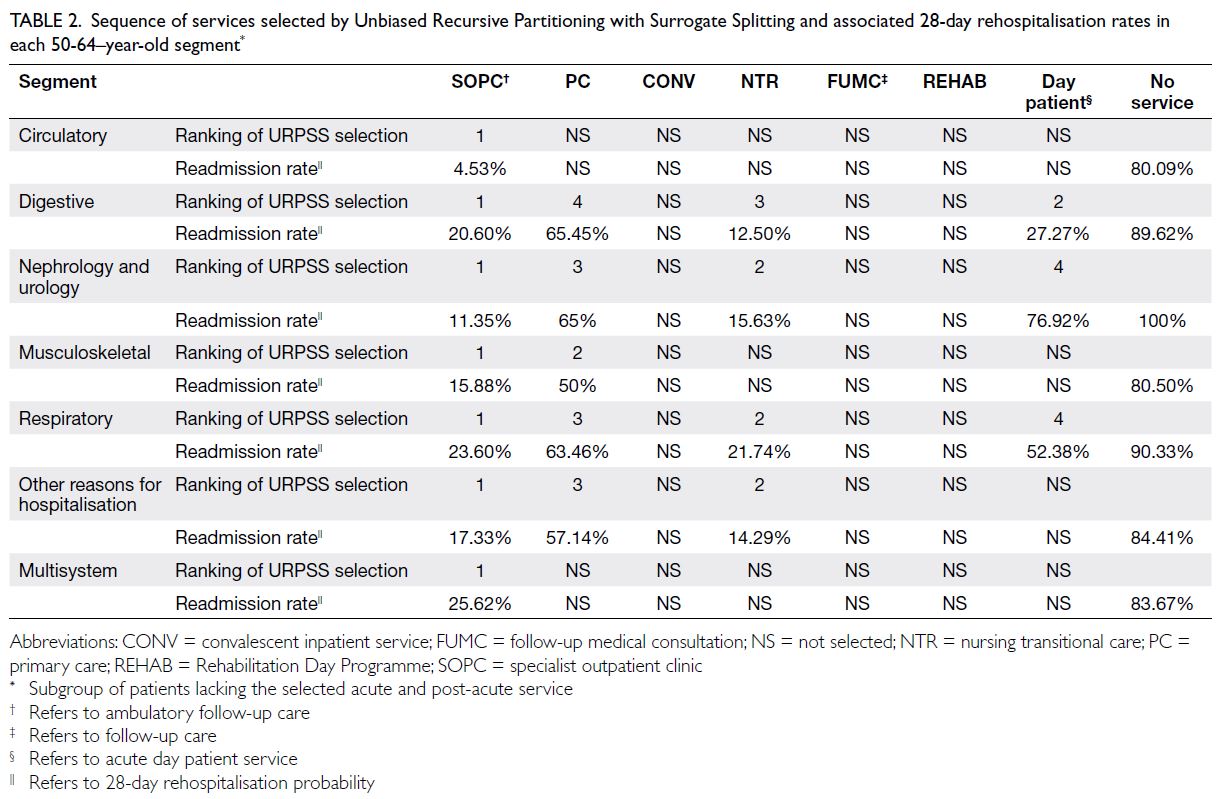

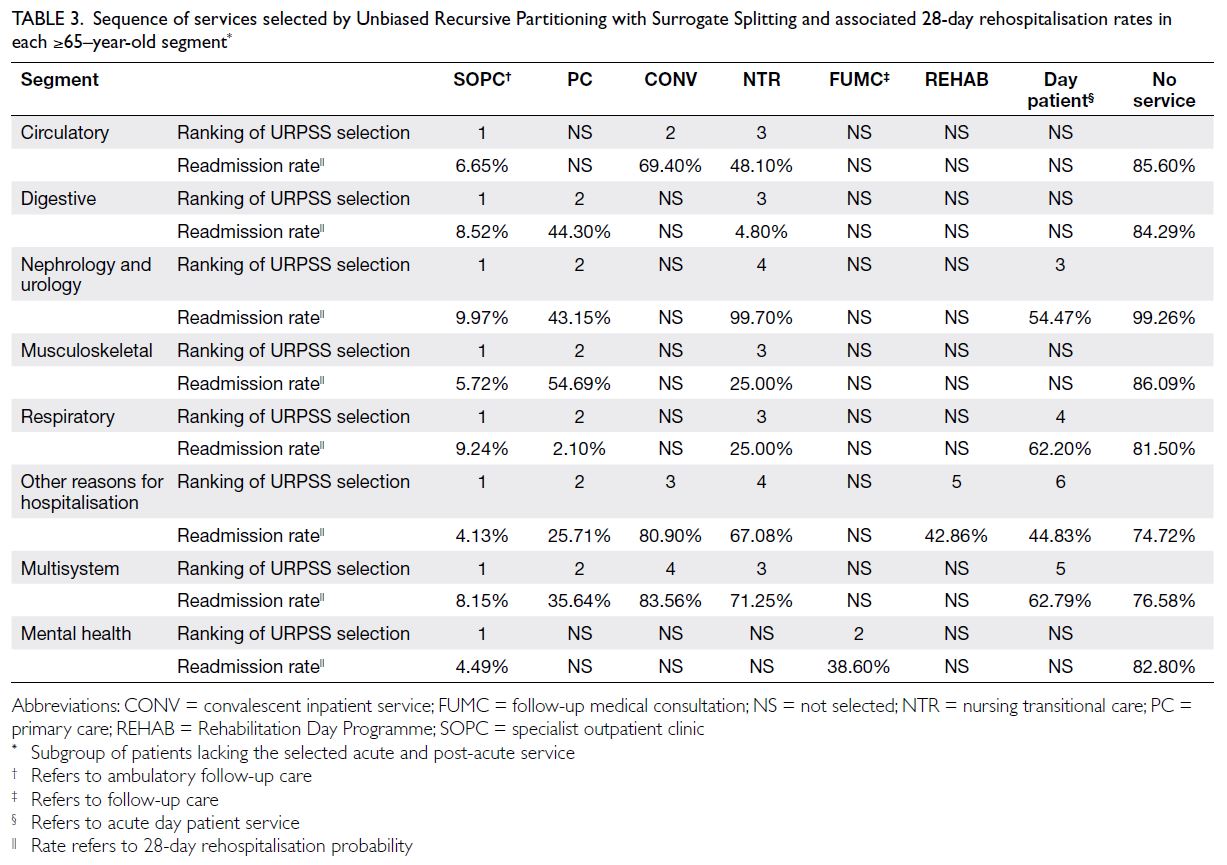

Tables 2 and 3 report the type, sequence (reflecting

the descending rank order of marginal contribution

feature importance), and associated 28-day

rehospitalisation rates of each PAC service selected

by the URPSS algorithm. With areas under the

receiver operating characteristic curve ranging

from 0.85 to 0.93, the URPSS algorithms classified

28-day rehospitalisation outcomes in every segment

partitioned from the two populations using features

selected for their unique contributions to outcomes.

Among all features in the pool to which the URPSSs

were applied (online supplementary Table 5), only

PAC-related features were selected to split segments

that had previously been partitioned from the

population using other features (eg, sex) that were

unrelated to PAC.

Table 2. Sequence of services selected by Unbiased Recursive Partitioning with Surrogate Splitting and associated 28-day rehospitalisation rates in each 50-64–year-old segment

Table 3. Sequence of services selected by Unbiased Recursive Partitioning with Surrogate Splitting and associated 28-day rehospitalisation rates in each ≥65–year-old segment

Our analyses revealed that, compared with

all other PAC services, specialist outpatient clinics

(SOPCs) had the greatest marginal contribution

to 28-day rehospitalisation outcomes among

patients with similar clinical profiles and acute

care utilisation patterns, even after adjusting for

the effects of the segments’ patient clinical profiles and acute care utilisation patterns on 28-day

rehospitalisations through conditional inference.

Additionally, SOPCs’ contribution to 28-day

rehospitalisation was not conditional on the effects

of other features. Consequently, the lowest 28-day

rehospitalisation rates were observed among SOPC

attendees across all homogeneous population

segments. Nevertheless, although SOPCs had the

highest marginal contribution feature importance—and were associated with the lowest 28-day

rehospitalisation rates—in all segments across

both populations, the 28-day rehospitalisation

rates among SOPC attendees were higher in every

segment of the 50-64–year-old population compared

with the corresponding segments of the ≥65–year-old

population (mean difference between segments

with the same MCC profiles: 9.5%).

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the 28-day

rehospitalisation rates were consistently the highest

among subpopulations within each segment that

remained unsplit after the sequential selection and

partitioning by features representing PAC services

that the URPSS identified as highly important to

28-day rehospitalisation outcomes (ie, the NS groups).

For example, among the 50-64–year-old population,

the mean difference in 28-day rehospitalisation rates between the NS groups and those in the same

segments who received SOPC care (the PAC service

with the greatest feature importance) was 70.01%;

the mean difference between the NS groups and

their corresponding full segments was 66.69%.

Similarly, among the ≥65–year-old population, the

mean difference between the NS groups and patients

in the same segments who received SOPC care was

76.28%; the mean difference between the NS groups

and their corresponding full segments was 62.26%.

Notably, whereas the NS groups consistently showed

the highest 28-day rehospitalisation rates among all

subpopulations, the NS groups of the 50-64–year-old

population exhibited a greater mean difference

in 28-day rehospitalisation rates compared with their

≥65–year-old counterparts (by a mean difference of

2.99%).

Clinical complexity and 28-day

rehospitalisation of the No Service groups

and their corresponding segments in the

populations aged 50-64 years and ≥65 years

The above analyses identified a subpopulation (ie,

the NS groups) within each segment that exhibited high 28-day rehospitalisation rates but lacked

effective PAC services. To provide a more in-depth

understanding of the NS groups, we compared

28-day rehospitalisation rates, the prevalence of

resource-intensifying co-morbidities, and the

presence of two or more chronic illnesses between

the NS groups and their corresponding segments,

as well as between the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old populations. Not all NS groups’ typical

patients shared the same CMGs as the medoids of

their corresponding segments, nor were the same

CMGs shared between the medoids of the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old populations. Chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was the

only CMG consistently identified as a medoid

CMG in both populations and their corresponding

subpopulations. Therefore, a more detailed analysis

was conducted on the segment and subpopulation

with COPD CMGs to illustrate factors contributing

to the differences between NS groups and their

corresponding segments, and between the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old populations.

Table 1 reports the ORs (and their associated

95% CIs and P values) for resource-intensifying co-morbidities, the presence of two or more chronic

illnesses, and 28-day rehospitalisations of NS groups

relative to their corresponding 50-64–year-old or

≥65–year-old population segments sharing the

same medoid CMGs. As shown in the table, even

when diseases of different systems were considered

across both populations, the NS groups exhibited

significantly higher rates of 28-day rehospitalisation

compared with their same-medoid-CMG segments

(pooled OR=19.27, 95% CI=17.86-20.79; P<0.001);

they also showed a greater prevalence of having two

or more chronic illnesses (pooled OR=1.84, 95%

CI=1.64-2.07; P<0.001).

Although resource-intensifying co-morbidity

is also a measure of clinical complexity, it was not

more likely to be found among NS groups than

among their same–medoid-CMG segments. Follow-up

analyses revealed that the pooled OR for the

≥65–year-old population was heterogeneous (Q

statistic=39.97, P<0.001), whereas the Q statistic for

pooled ORs in the 50-64–year-old population was

not statistically significant. Upon closer examination,

the rate of resource-intensifying co-morbidity was

indeed higher in NS groups of the 50-64–year-old

population than in their same–medoid-CMG

segments (pooled OR=1.23, 95% CI=1.00-1.52;

P=0.05); it was lower in the NS group population

aged ≥65 years than in their corresponding segments

(pooled OR=0.76, 95% CI=0.68-0.85; P<0.001).

The observation that the 50-64–year-old

population exhibits higher clinical complexity and

28-day rehospitalisation rates compared with their

≥65–year-old counterparts was directly examined

among same–medoid-CMG pairs of the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old population segments,

as well as among pairs of NS group populations

aged 50-64 years and ≥65 years (Table 1). Whereas

the 50-64–year-old population showed higher

rates of resource-intensifying co-morbidity and

28-day rehospitalisation compared with the ≥65–year-old population at both the segment and NS-group

levels, these differences were not statistically

significant (pooled ORs=1.27, 95% CI=0.55-2.93,

and 1.18, 95% CI=0.84-1.65, respectively). Follow-up

analysis revealed substantial heterogeneity in

the pooled statistics, attributable to significant

variation among the pooled ORs of NS-group

pairs (Q statistics=7.81-9.43; all P<0.05). Follow-up

segment-level analyses also showed significantly

lower prevalence of all study parameters in the

50-64–year-old population compared with the ≥65–year-old population: OR=0.56 (95% CI=0.52-0.59;

P<0.001), OR=0.22 (95% CI=0.20-0.24; P<0.001),

and OR=0.93 (95% CI=0.89-0.96; P<0.001) for rates

of resource-intensifying co-morbidity, the presence

of two or more chronic illnesses, and 28-day

rehospitalisation, respectively.

Given the high heterogeneity of pooled ORs for the NS-group CMG pairs, differences in

the prevalence of study parameters between the

50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old populations

were examined within individual NS-group pairs.

Follow-up analyses revealed that, although not

all NS-group CMG pairs showed higher rates

of resource-intensifying co-morbidity or 28-day

rehospitalisation in the 50-64–year-old population,

those that did—such as when the medoid CMG was

renal failure or COPD—also showed significantly

higher 28-day rehospitalisation rates compared

with their ≥65–year-old counterparts sharing the

same medoid CMGs. For example, in the case of

renal failure, the ORs were 63.11 (95% CI=50.26-79.38; P<0.001) and 1.35 (95% CI=1.06-1.70; P=0.01)

for resource-intensifying co-morbidity and 28-day

rehospitalisation rates, respectively (Table 1).

Finally, to consider differences in study

parameter prevalence between the NS group and

its corresponding segment when comparing clinical

complexity and 28-day rehospitalisation outcomes

between the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old

populations, we examined cases in which the CMG

was COPD. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

was the only CMG that served as the medoid of both

the population segment and the corresponding NS

group for the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old

populations, allowing us to adjust for differences

in study parameter prevalence between the NS

group and its full segment when comparing the

two age-groups. Our analyses revealed that, relative

to the statistics of the full segments, the ORs for

resource-intensifying co-morbidity, two or more

chronic illnesses, and 28-day rehospitalisation rates

were significantly greater in the 50-64–year-old NS

group than in the ≥65–year-old counterparts [ratios

of ORs=1.50 (95% CI=1.06-2.11; P=0.02), 1.17

(95% CI=1.01-1.37; P=0.04), and 2.34 (95% CI=1.84-2.96; P<0.001), respectively].

Discussion

Unmet post–acute care needs and age-related disparities

Patients aged 50 to 64 years who were discharged

without receiving algorithm-selected PAC services

(ie, the NS groups) were generally more likely to be

rehospitalised within 28 days of discharge than their

counterparts who shared similar clinical and acute

care utilisation profiles but received such services.

In some cases, the 50-64–year-old NS groups were

rehospitalised at even higher rates than the ≥65–year-old NS groups. Under these circumstances, the

50-64–year-old NS groups also exhibited higher rates

of resource-intensifying co-morbidity. This elevated

co-morbidity among patients aged 50-64 years who

experienced more frequent rehospitalisation than

their ≥65–year-old counterparts was exemplified by

NS groups whose clinical and acute care utilisation

profiles resembled the CMGs of typical patients

with renal failure and COPD—the same CMGs characterising typical patients in the ≥65–year-old

NS groups. In the case of COPD, the rates of co-morbidity,

chronic illnesses, and rehospitalisation

within the full segment could be directly considered

when comparing the 50-64–year-old and ≥65–year-old

NS groups.

Ambulatory care–sensitive case-mix profiles and preventable rehospitalisation

Similar to COPD, the majority of typical

patients’ CMGs in the full segments and NS groups

identified in the present study were considered

ambulatory care–sensitive conditions (ACSCs),31

for which hospitalisations are potentially avoidable

through timely and effective ambulatory care.

Because avoidable hospitalisations among ACSC

patients could be prevented with better access to

ambulatory and primary care services, it has been

argued that resources should be redistributed

from acute care to these services.32 Our findings

provide rare empirical support for this argument.

By comparing rehospitalisation rates among

subpopulations of patients with homogeneous

clinical profiles and acute care utilisation patterns

but differing PAC assignments, we demonstrated,

at a population level, the benefits of ambulatory

care (eg, specialist follow-up and in-home nursing

transitional care) and primary care in reducing

rehospitalisation rates among typical patient profiles

whose CMGs were ACSCs.

Notably, even ACSCs may progress into more

acute diagnoses, with a higher likelihood of co-morbidity

and elevated 28-day rehospitalisation

rates. For instance, whereas Angina or Arrhythmia

were the CMGs of typical patient profiles in the

full patient segments of the 50-64–year-old and

≥65–year-old populations, respectively, the CMG

of their NS groups’ typical patient profile was Heart

Failure; these patients exhibited higher rates of co-morbidities

and 28-day rehospitalisation. Similarly,

Digestive Malignancy was the CMG of the typical

patient profile in a 50-64–year-old NS group, which

showed higher rates of co-morbidities and 28-day

rehospitalisation than its corresponding full patient

segment, whose typical CMG was Symptom or Sign

of the Digestive System.

Post-discharge service gaps and policy implications

Despite such evidence, these services remain

largely unavailable for individuals in the studied

populations. For example, the average wait time for

SOPC appointments ranges from 9 to 111 weeks,33

in sharp contrast to the median interval between

discharge and rehospitalisation among NS patients,

which is 14 days. Given the constraints on healthcare

professional availability in the public sector, reducing

SOPC wait times may be challenging. Therefore, by

quantifying the benefits of different PAC services for

various patient profiles, the findings presented here

suggest the need for the following policy actions:

(1) procure specialist follow-up services from the

private sector and ensure effective public–private

service coordination within the parallel public and private tracks of the healthcare system studied;

and (2) enhance the provision of less scarce, near-equivalent

alternatives available in the community,

rather than relying solely on medical specialists.

Multi-morbidity in adults aged 50 to 64 years and the case for multidisciplinary tertiary prevention

In addition to the higher rehospitalisation

rates identified in the present study, typical patient

profiles with ACSC CMGs that lacked effective

PAC services also exhibited a high prevalence of

co-morbidities. The rates of co-morbidities and

28-day rehospitalisations were particularly high

among individuals aged 50 to 64 years who fit

these patient profiles. This finding aligns with

recent studies showing that younger patients with

diabetes—also a chronic ACSC—have significantly

greater co-morbidities and worse outcomes than

their older counterparts.34 Furthermore, we found

that younger patients not only have more complex

health needs but also benefit less from conventional

PAC services and are more likely to be rehospitalised

before receiving ambulatory or primary care. This

finding is consistent with current literature, which

indicates that effective rehospitalisation prevention

programmes for chronically ill patients with multiple

health problems,35 especially younger patients,

require a multidisciplinary approach to address

diverse needs such as smoking cessation,36 rather

than the conventional ‘assess-and-advise’ primary

care model of rehospitalisation prevention.37

Indeed, most evidence supporting the

benefits of multidisciplinary primary care for

chronic conditions is derived from intervention

studies targeting diseases that also represented the

CMGs of typical patients identified in our study

populations—particularly those who did not receive

PAC services deemed effective in reducing 28-day

rehospitalisation. For example, multidisciplinary

pulmonary rehabilitation programmes, which are

most effective in preventing rehospitalisation among

patients with COPD, include not only clinician-led

physical rehabilitation but also health-related

education, advice regarding exercise programmes,

targeted interventions addressing cognitive and

behavioural issues, and personalised care plans

tailored to individual needs.38 39 Similarly, community-based

cardiac rehabilitation programmes that

integrate cardioprotective therapeutics with

psychosocial care and lifestyle management are

most effective in preventing rehospitalisation

among patients with angina and arrhythmia—conditions that are often underdiagnosed in

acute care settings yet associated with high

rehospitalisation rates and natural progression

to heart failure if left untreated.40 Furthermore,

effective pain management programmes for patients

with pain-related musculoskeletal conditions—such as the inflammatory and reactive arthropathy

CMGs assigned to our typical patient profiles—are multidisciplinary in nature and combine physiotherapy with approaches that promote active

coping and self-management.41

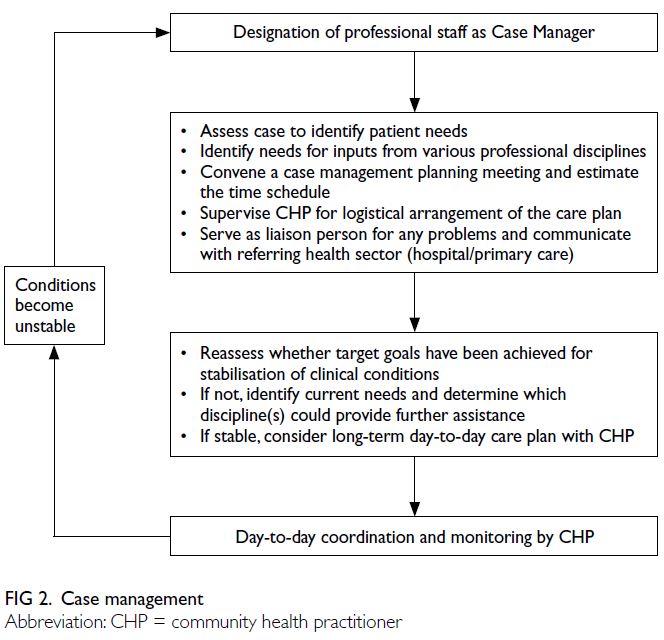

Precision-driven tertiary prevention: case management and population stratification

Patients with multiple chronic health

conditions benefit most from multidisciplinary

care but often require treatment from numerous

healthcare professionals across both primary and

secondary care settings. To mitigate the risk of care

fragmentation redundant patient assessments, a

case management approach has been advocated as

a holistic means of addressing the complex needs of

such patients (Fig 2). For example, patients with COPD

have diverse and evolving care needs throughout

their care journey,39 requiring care that is not only

multidisciplinary but also integrated through case

management. Effective case management for patients

with COPD involves healthcare professionals who

address the most pressing needs at the initial stage of

the care journey assuming the role of case manager,

supported by community health practitioners who

coordinate other professional services as required.42

Given the complexity of multidisciplinary care

needs in patients with multiple chronic conditions,

and the challenge of delivering the right intervention

from the right healthcare professionals to the right

patients at the right time, the training and provision

of case management can be enhanced through a

precision-driven approach. By leveraging advanced

data analytics and machine learning, such an approach

can accurately identify care needs and service gaps to

improve the integration of multidisciplinary care.43 44

The approach used in the present study—segmenting

patient populations based on diagnostic profiles and

patterns of acute and PAC service utilisation through

iterative applications of unsupervised and 28-day

rehospitalisation outcome–supervised machine

learning algorithms—can profile unmet needs and

service gaps among patient populations discharged

into the community. Thus, our study adds value to

a body of literature largely focused on identifying

homogeneous inpatient segments solely based on

diagnoses45 46 47 48 49 50 51 or cost,52 aimed at improving acute

care management.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the

data were solely derived from public hospitals

as information from private hospitals and other

healthcare providers outside the public system was

not accessible. However, it is worth noting that

public hospitals account for over 90% of inpatient

services. Second, the coding system may not capture

all patient health conditions because it mainly

focuses on chief complaints. Finally, the lack of

socio-demographic data limits the ability to generate

more precise predictions.

Conclusion

This hybrid machine learning analysis of electronic health records of discharged patient population showed that patients

aged 50 to 64 years with typical ambulatory care—sensitive case-mix profiles who did not receive

algorithm-selected PAC services had substantially

higher levels of multimorbidity and increased risk

of 28-day rehospitalisation compared with clinically

similar peers receiving such care. Integrating PAC

utilisation and clinical complexity indicators into

case-mix stratification can enable precision tertiary

prevention and guide the development of targeted,

multidisciplinary, case-managed services in the

community.

Author contributions

Concept or design: E Leung, A Lee, J Guan.

Acquisition of data: E Leung, J Guan, SCC Ching.

Analysis or interpretation of data: E Leung, J Guan, SCC Ching.

Drafting of the manuscript: E Leung, A Lee, FY Chen.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: E Leung, J Guan, SCC Ching.

Analysis or interpretation of data: E Leung, J Guan, SCC Ching.

Drafting of the manuscript: E Leung, A Lee, FY Chen.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As the Chief Editor of the journal, MCS Wong was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors declared

no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research was supported by the Strategic Public

Policy Research Funding Scheme of the Hong Kong SAR

Government (Project No.: S2019.A4.015.19S) awarded to A

Lee and E Leung; the Community Involvement Fund of the

Home Affairs Department, Hong Kong SAR Government,

through Sham Shui Po District Council (Project Nos.: 220179

and 220180) awarded to E Leung and A Lee; and the General

Research Fund of the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong

(Project No.: 9043763) awarded to FY Chen. The funders

had no role in the study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of

Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: SBRE-22-0386). The

requirement for patient consent was waived by the Committee

due to the use of unidentifiable information of participants in

the research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Vuik SI, Mayer E, Darzi A. A quantitative evidence base

for population health: applying utilization-based cluster

analysis to segment a patient population. Popul Health

Metr 2016;14:44. Crossref

2. Caldon LJ, Walters SJ, Reed JA, Murphy A, Worley A, Reed

MW. Case-mix fails to explain variation in mastectomy

rates: management of screen-detected breast cancer in a

UK region 1997–2003. Br J Cancer 2005;92:55-9. Crossref

3. Hof S, Fügener A, Schoenfelder J, Brunner JO. Case mix

planning in hospitals: a review and future agenda. Health

Care Manag Sci 2017;20:207-20. Crossref

4. Şentürk D, Chen Y, Estes JP, et al. Impact of case-mix

measurement error on estimation and inference in

profiling of health care providers. Commun Stat Simul

Comput 2020;49:2206-24. Crossref

5. Tumlinson A, Altman W, Glaudemans J, Gleckman H,

Grabowski DC. Post–acute care preparedness in a COVID-19 world. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:1150-4. Crossref

6. Lee MC, Wu TY, Huang SJ, Chen YM, Hsiao SH, Tsai CY.

Post–acute care for frail older people decreases 90-day

emergency room visits, readmissions and mortality: an

interventional study. PLoS One 2023;18:e0279654. Crossref

7. Jamei M, Nisnevich A, Wetchler E, Sudat S, Liu E. Predicting

all-cause risk of 30-day hospital readmission using artificial

neural networks. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181173. Crossref

8. Siddique SM, Tipton K, Leas B, et al. Interventions to

reduce hospital length of stay in high-risk populations: a

systematic review. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2125846. Crossref

9. McGilton KS, Vellani S, Krassikova A, et al. Understanding

transitional care programs for older adults who experience

delayed discharge: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr

2021;21:210. Crossref

10. Cao YJ, Wang Y, Mullahy J, Burns M, Liu Y, Smith M.

The relative importance of hospital discharge and patient

composition in changing post–acute care utilization and

outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv

Insights 2023;16:11786329231166522. Crossref

11. White HK. Post–acute care: current state and future

directions. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:392-5. Crossref

12. Geng F, Liu Z, Yan R, Zhi M, Grabowski DC, Hu L. Post–acute care in China: development, challenges, and path

forward. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2023;25:61-8. Crossref

13. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Case Mix

Decision-Support Guide: CMG+. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2015.

14. Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased recursive

partitioning: a conditional inference framework. J Comput

Graph Stat 2006;15:651-74. Crossref

15. Guan J, Leung E, Kwok KO, Chen FY. A hybrid machine

learning framework to improve prediction of all-cause

rehospitalization among elderly patients in Hong Kong.

BMC Med Res Methodol 2023;23:14. Crossref

16. Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Choi BY. Unmet healthcare needs

and healthcare access gaps among uninsured U.S. adults aged 50-64. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:2711. Crossref

17. Hof S, Fügener A, Schoenfelder J, Brunner JO. Case mix

planning in hospitals: a review and future agenda. Health

Care Manag Sci 2017;20:207-20. Crossref

18. Fetter RB, Shin Y, Freeman JL, Averill RF, Thompson JD.

Case mix definition by diagnosis-related groups. Med Care

1980;18(2 Suppl):iii, 1-53.

19. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS.

Medicare program; changes to the hospital inpatient

prospective payment systems and fiscal year 2008 rates.

Fed Regist 2007;72:47130-8175.

20. Fries BE, Schneider DP, Foley WJ, Gavazzi M, Burke R,

Cornelius E. Refining a case-mix measure for nursing

homes: Resource Utilization Groups (RUG-III). Med Care

1994;32:668-85. Crossref

21. Pope GC, Kautter J, Ellis RP, et al. Risk adjustment of

Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC

model. Health Care Financ Rev 2004;25:119-41.

22. Aschengrau A, Seage GR. Essentials of Epidemiology

in Public Health. 3rd edition. Burlington [MA]: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2013.

23. Tripepi G, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, Zoccali C. Stratification

for confounding—part 1: the Mantel-Haenszel formula.

Nephron Clin Pract 2010;116:c317-21. Crossref

24. Shrier I, Pang M. Confounding, effect modification, and the

odds ratio: common misinterpretations. J Clin Epidemiol

2015;68:470-4. Crossref

25. Knol MJ, Le Cessie S, Algra A, Vandenbroucke JP,

Groenwold RH. Overestimation of risk ratios by odds

ratios in trials and cohort studies: alternatives to logistic

regression. CMAJ 2012;184:895-9. Crossref

26. Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis

of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer

Inst 1959;22:719-48.

27. Sudhakar SK, Sridhar S, Char S, Pandya K, Mehta K.

Prevalence of comorbidities post mild traumatic brain

injuries: a traumatic brain injury model systems study.

Front Hum Neurosci 2023;17:1158483. Crossref

28. Lloyd T, Deeny SR, Steventon A. Weekend admissions

may be associated with poorer recording of long-term

comorbidities: a prospective study of emergency

admissions using administrative data. BMC Health Serv

Res 2018;18:863. Crossref

29. le Cessie S, Nagelkerke N, Rosendaal FR, van Stralen KJ,

Pomp ER, van Houwelingen HC. Combining matched and

unmatched control groups in case-control studies. Am J

Epidemiol 2008;168:1204-10. Crossref

30. Caliński T, Harabasz J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Commun Stat 1974;3:1-27. Crossref

31. Lin PJ, Zhong Y, Fillit HM, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ.

Hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions and unplanned readmissions among Medicare

beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement

2017;13:1174-8. Crossref

32. Grabowski DC, Mor V. Nursing home care in crisis in the

wake of COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324:23-4. Crossref

33. Hospital Authority. Waiting time for stable new case

booking at specialist out-patient clinics. 2024. Available

from: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/sopc/dw_wait_ls.pdf. Accessed 5 Jul 2024.

34. Hong SN, Mak IL, Chin WY, et al. Age-specific associations

between the number of co-morbidities, all-cause mortality

and public direct medical costs in patients with type 2

diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Obes

Metab 2023;25:454-67. Crossref

35. Fong BY, Law VT, Lee A. Primary Care Revisited:

Interdisciplinary Perspectives for a New Era. Singapore:

Springer; 2020. Crossref

36. Al Quait A, Doherty P. Does cardiac rehabilitation favour

the young over the old? Open Heart 2016;3:e000450. Crossref

37. Lorig K, Holman H, Sobel D, Laurent D. Living a Healthy

Life with Chronic Conditions: Self-management of

Heart Disease, Arthritis, Diabetes, Asthma, Bronchitis,

Emphysema and Others. 3rd edition. Boulder [CO]: Bull

Publishing Company; 2006.

38. Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, et al. Reduction of hospital

utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease: a disease-specific self-management intervention.

Arch Intern Med 2003;163:585-91. Crossref

39. Cravo A, Attar D, Freeman D, Holmes S, Ip L, Singh SJ.

The importance of self-management in the context of

personalized care in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon

Dis 2022;17:231-43. Crossref

40. Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation.

BMJ 2015;351:h5000. Crossref

41. Soares JJ, Sundin O, Grossi G. The stress of musculoskeletal

pain: a comparison between primary care patients in

various ages. J Psychosom Res 2004;56:297-305. Crossref

42. Tong KW, Fong KN. Community Care in Hong Kong:

Current Practices, Practice-Research Studies and Future

Directions. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong

Press; 2014.

43. Talias MA, Lamnisos D, Heraclides A. Editorial: Data

science and health economics in precision public health.

Front Public Health 2022;10:960282. Crossref

44. Leung E, Lee A, Tsang H, Wong MC. Data-driven service

model to profile healthcare needs and optimise the

operation of community-based care: a multi-source data

analysis using predictive artificial intelligence. Hong Kong

Med J 2023;29:484-6. Crossref

45. Chong JL, Lim KK, Matchar DB. Population segmentation

based on healthcare needs: a systematic review. Syst Rev

2019;8:202. Crossref

46. Mechanic R. Post–acute care—the next frontier for

controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med 2014;370:692-4. Crossref

47. Nnoaham KE, Cann KF. Can cluster analyses of linked

healthcare data identify unique population segments in

a general practice-registered population? BMC Public

Health 2020;20:798. Crossref

48. Lafortune L, Béland F, Bergman H, Ankri J. Health status

transitions in community-living elderly with complex care

needs: a latent class approach. BMC Geriatr 2009;9:6. Crossref

49. Liu LF, Tian WH, Yao HP. Utilization of health care

services by elderly people with National Health Insurance

in Taiwan: the heterogeneous health profile approach.

Health Policy 2012;108:246-55. Crossref

50. Eissens van der Laan MR, van Offenbeek MA, Broekhuis H,

Slaets JP. A person-centred segmentation study in elderly

care: towards efficient demand-driven care. Soc Sci Med

2014;113:68-76. Crossref

51. Joynt KE, Figueroa JF, Beaulieu N, Wild RC, Orav EJ,

Jha AK. Segmenting high-cost Medicare patients into

potentially actionable cohorts. Healthc (Amst) 2017;5:62-7. Crossref

52. Davis AC, Shen E, Shah NR, et al. Segmentation of high-cost

adults in an integrated healthcare system based on

empirical clustering of acute and chronic conditions. J Gen

Intern Med 2018;33:2171-9. Crossref