© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

The introduction of trained nurses at Government Civil Hospital in the nineteenth century

TW Wong, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)

Member, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

Government Civil Hospital (GCH) was founded

in 1849, about 7 years after Hong Kong became a

British colony. When Dr Philip Burnard Chenery

Ayres arrived in 1873 to take up the post of colonial

surgeon, he deemed the hospital, which had been

converted from an old private house, entirely

unsuitable. Although Ayres strongly advocated

for its replacement, it was ultimately a typhoon

that destroyed the old building, prompting the

government to construct a new purpose-built

hospital on the aptly named Hospital Road in 1879.

This new facility served as the main government

hospital for the civilian population until it was

replaced by Queen Mary Hospital in 1937.1

While Western-trained doctors were

appointed medical superintendent at GCH, nursing

care was left to the European wardmasters and

Chinese coolies who had no formal training. Dr John

Murray, colonial surgeon (1859-1872), commented

in his annual report, “If it were possible to induce the

Sisters of Charity to undertake this duty, the benefit

would be incalculable.”2 Something close to this wish

came true but not until much later.

Among his many achievements, Dr James

Cantlie—one of the founders of the Hong Kong

College of Medicine and known for rescuing his

student Dr Sun Yat-sen after his kidnapping by

the Qing Embassy in London—is credited with

introducing the first trained British nurse to Hong

Kong. In 1888, he invited Maude Ingall to serve as

a private nurse. When Cantlie founded the Peak

Hospital in 1890, Ingall became its matron. She also

served as nurse to Governor Sir George William

Des Voeux, who later supported the introduction of

trained nurses to the GCH as proposed by Dr John

Mitford Atkinson, GCH’s medical superintendent

(1887-1897).3

Previously, Dr Atkinson had worked in

London, where hospitals had been reforming

and revolutionising nursing since the middle of

the century. By the 1880s, trained nurses were

widely recognised by the medical community as

a cornerstone of hospital treatment, and all the

London teaching hospitals—with the exception

of St Thomas’s—had their own nursing schools.4 Dr Atkinson proposed hiring five Europe-trained

nurses from England, including one to be head

nurse.5 Governor Des Voeux supported the scheme

in principle but preferred to hire five nursing sisters

from a religious background instead.6 Eventually,

in 1889, five French nursing sisters from a branch

of St Vincent de Paul were employed. The scheme

was terminated 1 year later; although the nursing

sisters were very conscientious in their work, their

training did not meet the doctors’ requirements.

Moreover, they were too few to cover night duties.

Atkinson’s original proposal was adopted in 1890,

with the alteration that six nursing sisters from

England would be sought, as admissions to GCH had

increased.7

The six British nursing sisters—one head nurse,

two day nurses, two night nurses and one special-duty

nurse—arrived in November 1890. At that

time, the hospital compound could accommodate

approximately 130 patients. The nurses were

initially housed in temporary quarters at the new

Lock Hospital facing Queen’s Road West, before

moving to new nursing quarters on High Street in

1892.8 The superintendent consulted with the head

nurse every morning in his office at 9:30 am. The

day nurses worked from 9 am to 9 pm and were

expected to join the superintendent on his morning

rounds of her wards and document his treatment

instructions. The day nurses administered medicines

as prescribed to their patients, monitored their

patients’ temperatures and ensured their hygiene,

especially for those patients who were unable to

look after themselves. The night nurses worked from

9 pm to 9 am. They received handover from the day

nurses so as to be fully acquainted with the seriously

ill patients’ conditions. In other ways, their duties

were the same as those of the day nurses.9

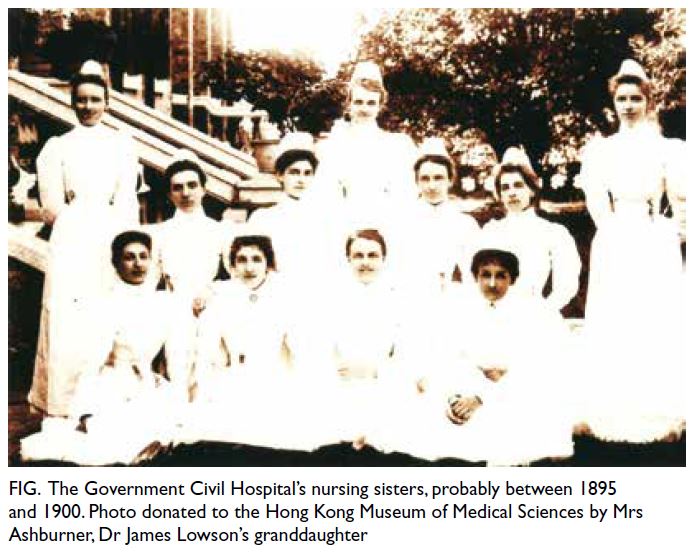

The nurses wore uniforms to distinguish them

from other workers in the hospital (Fig). The uniform

was similar to those worn in contemporary London

hospitals and consisted of a full-length bib and apron

over a dress. Other accessories included a cap, collar,

and cuffs. The nurses often carried a chatelaine,

bearing scissors, forceps, tongue depressors, and

other useful tools.

Figure. The Government Civil Hospital’s nursing sisters, probably between 1895 and 1900. Photo donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences by Mrs Ashburner, Dr James Lowson’s granddaughter

The nurses’ performance earned high praise

from GCH’s doctors, contributing to a growing

number of private patients choosing to attend the

hospital. The sisters faced a real challenge in 1894

when bubonic plague hit the colony. Although

there were now nine nurses, they also covered the

infectious disease hospital at Kennedy Town and the hospital ship Hygeia. Dr James Lowson, the medical

officer in charge of the hospitals, was full of praise

for the sisters, “If ever this colony has had reason

to congratulate itself, it was when we were able to

procure well-trained British nurses… had it not been

for their presence, there could have been no well-run

epidemic hospital during last summer.”10

Plague returned almost annually for the next 30

years, sadly claiming the lives of two nursing sisters

in 1898. In their honour, the Hong Kong community

made a striking clock, a wooden chest, and a silver

rose bowl, which were kept in the sisters’ mess.11

Following the plague epidemic, the medical

department was reviewed by a committee. At the

committee hearing, Lowson suggested training

local girls to meet the increased demand for nurses.

However, GCH’s matron doubted whether there

was enough experience at the hospital to train new

nurses. In any case, locally trained nurses could not

replace the sisters. Instead, the matron proposed

taking in two Eurasian girls as an experiment.12 The

first probationer was appointed in September 1896,

and a total of 16 were recruited up until 1904. Only

three completed the 3-year probation.13 The first six

male nurses (dressers) in the history of GCH were

appointed in 1916. The government only started to

train local Chinese nurses in 1921, but nurses from

Britain continued to take the helm until long after

the Second World War.1 A local Chinese nurse did

not assume the top role of principal nursing officer

until 1979.

References

1. Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society. Plague, SARS and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2006: 86-8.

2. Murray J. Hong Kong Colonial Surgeon’s Report for 1868. Hong Kong Blue Book, 3 Apr 1869.

3. Stewart JC. The Quality of Mercy: The Lives of Sir James and Lady Cantlie. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Rowan Books; 1983: 52.

4. Helmstadter C. Early nursing reform in nineteenth-century London: a doctor-driven phenomenon. Med Hist 2002;46:325-50. Crossref

5. Atkinson J. Report from the Superintendent of the Civil Hospital for 1887. Hong Kong Government Gazette 1888 (Supplement), 14 Jul 1888.

6. Des Voeux to Knutsford. 2 Jul 1888. Colonial Office CO129/238: 8-12.

7. Fleming to Knutsford. 7 Apr 1890. Colonial Office CO129/244: 328-37.

8. John Atkinson. Report from the Superintendent of the Civil Hospital for 1890. Hong Kong Government Gazette 1891 (Supplement), 2 Apr 1891.

9. Fleming to Knutsford. 7 Apr 1890. Colonial Office CO129/244: 345-7.

10. Lowson JA. The epidemic of bubonic plague in Hong Kong, 1894. Ind Med Gaz 1897;32:45-59.

11. Stratton D. History of nursing in government hospitals. Hong Kong Nurs Jr 1972;May:34-7.

12. Medical Committee Report on the Plague, 3 April 1895: 11-4. Available from: http://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkgro/view/s1895/1457.pdf. Accessed 24 Jun 2025.

13. Nursing Probationers. 22 Oct 1904. Colonial Office CO129/324: 182-4.