Hong Kong Med J 2023 Oct;29(5):459–61 | Epub 19 Sep 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Ultrasound-guided spinal anaesthesia in a patient with achondroplastic dwarfism and scoliosis: a case report

Banu Kilicaslan, MD

Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Faculty of Medicine, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey

Corresponding author: Dr Banu Kilicaslan (banuk9oct@gmail.com)

Case presentation

In February 2019, a 27-year-old woman who was

classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists

class III and 8 weeks pregnant presented for elective

therapeutic curettage and tubal ligation. She was

110 cm tall and weighed 30 kg. Her medical history

was notable for thoracolumbar kyphoscoliosis,

congenital dwarfism, and restrictive lung disease.

The patient’s medical history revealed that her

previous two pregnancies were terminated due to

shortness of breathing, reduced exercise tolerance,

and the possibility that progressing pregnancy might

create a life-threatening condition, first one in the

17th week and the other one in the 22nd week of

pregnancy. Her airway assessment was normal but

pulmonary function testing revealed a restrictive

lung disease. Ultrasound-guided spinal anaesthesia

was planned.

In the operating room, after standard

monitorisation, she was placed in a sitting position.

The midline of the spines and intervertebral disc

space were impossible to palpate because of the

severely rotated lumbar spines by marked scoliosis.

Preprocedural ultrasound scan using curved array

probe 2-5 MHz with LOGIQ e R7 ultrasound system

(GE HealthCare, Washington DC, United States) for

marking of insertion site were conducted in both

paramedian longitudinal and transverse planes at

different intervertebral levels.

In the scanning of the paramedian

longitudinal plane, the transducer was placed over

the lumbosacral spine approximately 2 cm lateral

to the midline in a cephalad-caudad direction to

find the appropriate lumbar interlaminar spaces

(the ligamentum flavum–dura mater complex and

posterior face of the vertebral body). The L2-L3 to

L4-L5 interlaminar spaces were identified. In the

transverse plane scanning, deeper structures were

visible between the spinous process. In this view,

the presence of bilateral transverse processes in the

same plane was the clue for the correct intervertebral

space. In this space, the vertebral column did not

rotate due to scoliosis and was the most suitable

intervertebral space for the needle puncture. The

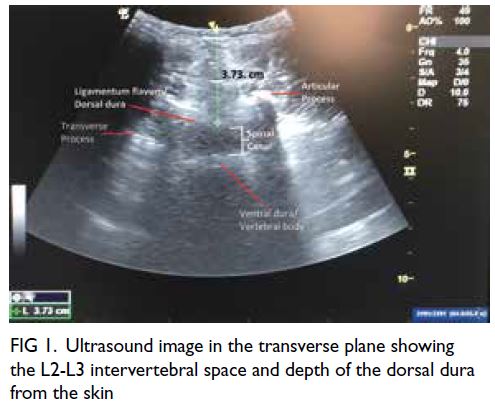

depth of the dorsal dura from the skin was measured as 3.73 cm in transverse view (Fig 1). The appropriate

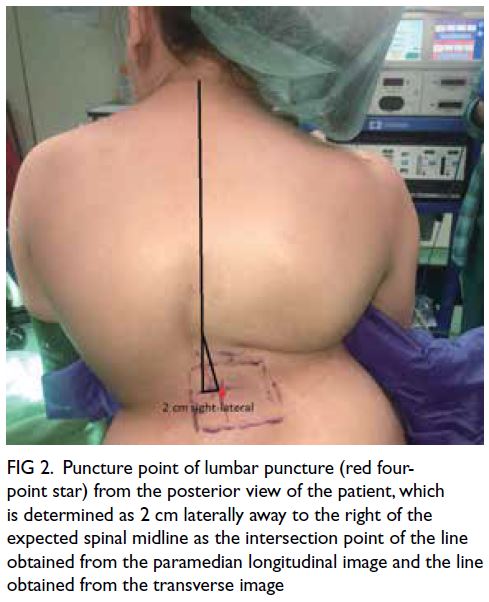

intervertebral space (L2-L3) was determined to be 2

cm laterally away to the right of the expected spinal

midline as the intersection point of the line obtained

from the paramedian longitudinal image and the line

obtained from the transverse image (Fig 2).

Figure 1. Ultrasound image in the transverse plane showing the L2-L3 intervertebral space and depth of the dorsal dura from the skin

Figure 2. Puncture point of lumbar puncture (red four-point star) from the posterior view of the patient, which is determined as 2 cm laterally away to the right of the expected spinal midline as the intersection point of the line obtained from the paramedian longitudinal image and the line obtained from the transverse image

After aseptic precautions, spinal anaesthesia

was performed by using 5-mg 0.5% hyperbaric

bupivacaine, with 10-μg fentanyl (1.2 mL in volume)

at the L2-L3 interspace without any complications.

The sensorial block was achieved up to the T4

dermatome level bilaterally and the patient was

sedated with dexmedetomidine (200 mcg/2 mL).

Motor functions regressed to her basal level 4 hours

after the initial intrathecal injection and the sensory

component of the block returned by 5 hours.

The patient was discharged on postoperative

day 2 uneventfully without postdural puncture

headache and back pain. A follow-up 1 month after

the surgery showed no further deterioration in her

neurological condition.

Discussion

This case illustrates two important points. First, the transverse plane image shows the rotation point of

the vertebral column better than the longitudinal plane; thus, this makes it easier to decide on the

most appropriate intervertebral puncture point

in the placement of a spinal block in a patient

with abnormal spinal anatomy. Second, this case

highlights the value of a systematic approach and an

individual risk-benefit ratio on a case-by-case basis

when performing neuraxial anaesthesia in patients

with severe scoliosis and dwarfism.

Shiang et al1 demonstrated that nearly all cases of achondroplasia are autosomal dominant and most

of those with achondroplasia will have a normal or

near-normal life expectancy. Therefore, they may live

long enough to experience anaesthesia for various

reasons. Clinical features that may be important for

anaesthesia management are midfacial abnormality,

craniocervical constriction, thoracolumbar

kyphosis, lumbosacral spinal stenosis, and cardiac

and pulmonary abnormalities.

The patient whom we have described with

achondroplastic dwarfism resulting severe in

scoliosis and moderate restrictive lung disease

had a potential risk for general anaesthesia due to

instability of the cervical spine, limited respiratory

reserve, and predisposition to the risk of malignant

hyperthermia. On the other hand, scoliosis and

spinal stenosis might further complicate patient

management with neuraxial anaesthesia technique.2

In our case, the patient’s previous two pregnancies

were terminated without using any anaesthetic

methods. The terminations were performed

by medical abortus (200 mcg oral and vaginal misoprostol) with intramuscular meperidine

analgesia. For the intervention in our case, spinal

anaesthesia was planned after mutual consent had

been achieved with the patient and the medical

team. Because of spinal deformity of the patient,

spinal anaesthesia was predicted to be challenging

even with ultrasound assistance.2 3

The drug and the dosage choice for spinal

anaesthesia in achondroplastic patients with severe

scoliosis may be of concern, as an unpredictable

spread of drug may contribute to a high blockade

that could be catastrophic in patients with a difficult

airway and limited pulmonary reserve. It has been

reported that a satisfactory block level was obtained

with an administration of 0.06 mg/cm height of

intrathecal bupivacaine.4 In the present case, as

the height of the patient was 110 cm and the body

mass index was 24.8 kg/m2, 5-mg bupivacaine and

10-μg fentanyl (1.2 mL in volume) were administered

intrathecally, and a T4-level block was obtained.

For local anaesthetic for spinal anaesthesia in these

patients, we do not recommend dosages >0.06 mg/cm

height to avoid complications caused by abnormal

block levels.

In our patient in whom we had predicted

difficult spinal anaesthesia, we preferred to use

ultrasound before the procedure for landmark

identification. Numerous reports indicate that this

application facilitates technical performance in

obstetric and paediatric patients and in patients

with difficult spinal anatomy.5 However, real-time

ultrasound guidance may provide additional

advantages by taking into account the positional

changes of the patient during the procedure. Ravi et al6

compared the efficacy of real‑time ultrasound‑guided

paramedian approach and preprocedural ultrasound

landmark‑guided paramedian approach in obese

patients. They determined that the time taken for

the identification of the space and for successful

lumbar puncture, and the number of attempts and

passes was more in the latter group as compared

to the former group.6 Although it is not technically

difficult to recognise spinal spaces with real-time

ultrasonography, the success rates for spinal

anaesthesia were similar for both techniques.6 Real-time

ultrasonography may be a better alternative as

it can show all structures that cannot be observed

during the procedure with ‘pre-procedural

ultrasonography’.

An experienced practitioner can achieve >90%

success rate in identifying the epidural space in

difficult situations using ultrasonography, as in the

current patient with difficult spinal anatomy.5 In our

experience, a single screening method of ultrasound

imaging in the transverse plane gives working

knowledge about the anatomical structures. Thus,

the asymmetry of structures on the two sides of the

spinal canal, mainly the articular and the transverse processes in the interspace, can be used as a guide

to determine the level of the rotation on the spinal

column. In our patient, no anatomical landmarks

were identifiable, and it was impossible to detect the

level of rotation of scoliosis. By using ultrasound, we

precisely determined the L2-L3 intervertebral space

available for the placement of spinal block and also

the depth of the dorsal dura from the skin that was

measured as 3.73 cm in the transverse view.

In conclusion, ultrasound-guided spinal

anaesthesia is feasible and can greatly facilitate a

spinal technique, especially in the transverse plane, in

the presence of severe scoliosis with achondroplastic

dwarfism.

Author contributions

The author contributed to the concept or design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. The author had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and takes responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Dr Coskun Salman and his team at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hacettepe

University for their sincere support of taking care of the

patient during and after the operation.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has provided informed consent for the

publication of the report along with the data, radiological

images, and photographs.

References

1. Shiang R, Thompson LM, Zhu YZ, et al. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarfism, achondroplasia. Cell 1994;78:335-42. Crossref

2. Mikhael H, Vadivelu N, Braveman F. Safety of spinal anesthesia in a patient with achondroplasia for cesarean section. Curr Drug Saf 2011;6:130-1. Crossref

3. Lange EM, Toledo P, Stariha J, Nixon HC. Anesthetic management for cesarean delivery in parturients with a diagnosis of dwarfism. Can J Anaesth 2016;63:945-51. Crossref

4. Samra T, Sharma S. Estimation of the dose of hyperbaric bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia for emergency caesarean section in an achondroplastic dwarf. Indian J Anaesth 2010;54:481-2. Crossref

5. Perlas A, Chaparro LE, Chin KJ. Lumbar neuraxial ultrasound for spinal and epidural anesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016;41:251-60. Crossref

6. Ravi PR, Naik S, Joshi MC, Singh S. Real-time ultrasound-guided spinal anaesthesia vs pre-procedural ultrasound-guided spinal anaesthesia in obese patients. Indian J Anaesth 2021;65:356-61. Crossref